1. Introduction

Rapid urbanisation, population growth, and socio-economic development have caused a 3-4% increase in phosphorus (P) demand annually leading to an accelerated P supply depletion [

1,

2]. Hence, it is expected that the future global security of agriculture and food (agri-food) systems will be compromised by 2050 if P extraction continues to increase [

3]. Moreover, the P in the agri-food supply chains following a linear pathway from phosphate rock mining for fertiliser production would eventually end up in various waste streams that cause adverse environmental impacts such as eutrophication in water resources [

4]. Developing countries with emerging economies are greatly affected with eutrophication and problems with sanitation due to high population density, increase of anthropogenic activities, and lack of appropriate sewage treatment systems or sanitation systems [

5]. Particularly in the Philippines, 84% of the households use septic tank as an onsite sanitation system to dispose and treat human wastes since it is cheaper, but the design commonly installed does not incorporate a leach field, hence without regular desludging, the raw septage would overflow and leak directly to the environment posing health risks [

6].

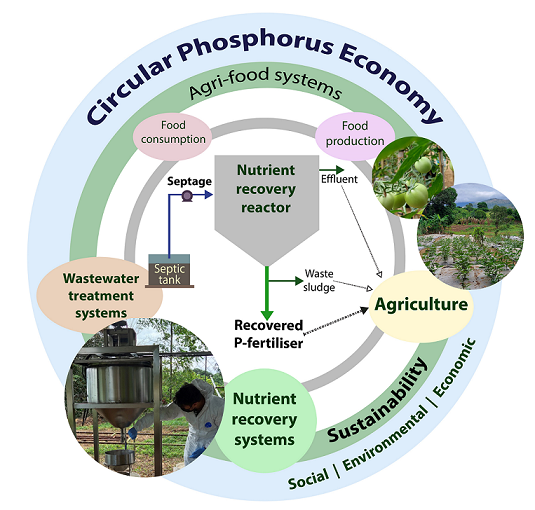

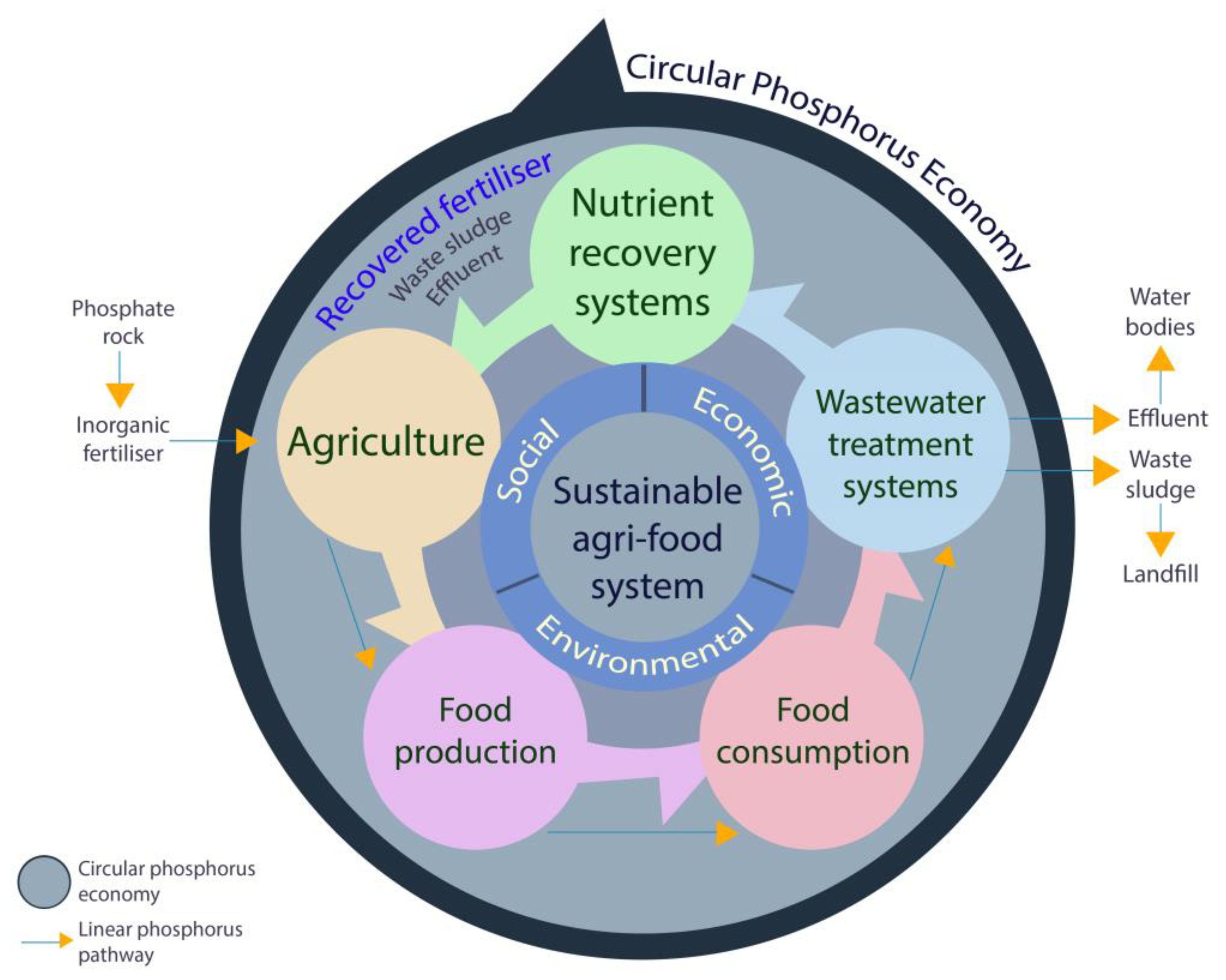

A paradigm-shift to a resource-oriented sanitation system could play an important role in addressing the challenges and risks with the linear P pathway through the concept of circular economy. Circular P economy is the sustainable management of P from resources, materials, and products within the economy while minimising waste generation through recycling and recovery from the waste stream endpoints from the linear P flows [

7]. This implies that P can be recovered from waste streams to be used back as a high-value product for various economic sectors. Agri-food systems connected to wastewater streams and water body sinks have the most potential for recovery [

8]. This will supplement the decreasing supply of P while minimising the end-point wastes [

9].

An established nutrient recovery process that is already implemented in some wastewater treatment plants to recover P is the chemical precipitation to form calcium phosphates (Ca

5(PO

4)

3OH) and struvite MgNH

4PO

4·6H

2O [

10]. Although calcium phosphate could be an alternative source of P for industries, it needs further processing to be used efficiently for agriculture [

11]. For agri-food systems, phosphorus recovered as struvite is preferred because of production efficiency while promoting economic sustainability [

12,

13]. Struvite is a high-value slow-release fertiliser that can be typically recovered from wastewater through the addition of magnesium salts at alkaline condition [

14,

15]. Several studies have been reported on the use of struvite as fertiliser to different kinds of crops where it produced higher or similar crop yields compared to other commercial fertilisers [

16,

17,

18]. A lot of studies were done solely in production of struvite from wastewater feedstock but these studies do not usually proceed to its application to crops [

19].

The typical wastewater input feedstock used for P recovery via precipitation are dewatering liquor, digestate (from anaerobic digestion) and waste activated sludge liquor from domestic wastewater, and animal manure [

20]. Although recovery from urine has been widely studied [

21], the use of human wastes from septic tank sludge or septage has been rarely explored because of potential microbial contaminants and low social acceptance [

22]. Septage or fecal sludge is generated from raw or partially digested blackwater in an onsite sanitation system (e.g. septic tanks after collection, storage, or treatment) [

23]. It contains an average of 215 mg/L of phosphate, 96.3 mg/L of total phosphorus, 1,300 mg/L of total nitrogen and 1,805 mg/L ammonia nitrogen [

24]. Septage has minimal heavy metal concentrations and hence, it can be used as a non-hazardous phosphorus source for agriculture application and a clean raw material for industry use [

24,

25,

26]. It was also found that organic contamination in fecal sludge is 95% lower than in regulations on fertiliser for some European countries [

27,

28]. Therefore, the potential of P and N recovery from septage for agri-food applications can be considered advantageous compared to other wastewater streams.

Struvite has been successfully recovered as a macronutrient fertiliser from blackwater effluent or supernatant with around 90% recovery rate [

27,

29]. The struvite produced contained minimal quantities of heavy metals and reduction of pathogen levels was observed during precipitation. These few studies on struvite recovery from septage are focused on the liquid component, either the supernatant, effluent, or liquor but the potential of the solid component or sludge of the septage has been hardly explored. Particularly for septic tanks, the wastewater undergoes partial aerobic-anaerobic digestion that captures significant P and N content in the sludge [

26]. Hence, the maximum potential of nutrient recovery from septage is not yet thoroughly investigated. Consequently, hydrolysis could be used as a pre-treatment method for septage to release the nutrients from the sludge into liquid soluble components, as what has been done in sewage sludge to maximise nutrient recovery.

Hydrolysis is typically used as pre-treatment of sludge to release soluble organics that can be an additional carbon source for subsequent nutrient removal processes [

30]. To optimise nutrient recovery from wastewater, this process has also been applied in some studies to release phosphorus into a soluble form for nutrient recovery and removal processes. Hydrolysis could release around 75% of P (800-900 mg TP/L) from initial sludge (700-800 mg P/L were dissolved from 1,100-1,200 mg P/L sludge) [

31]. Though there were few studies on hydrolysis of sewage sludge, there are no known studies done yet on the hydrolysis of septage, considering that it has lower, if at all, heavy metal contamination compared to sewage sludge [

25]. Moreover, most of the studies on hydrolysis focus more on the release of soluble organic components such as soluble chemical oxygen demand and volatile fatty acids yet only a few focus more on the release phosphates and ammonium for nutrient recovery [

32].

In this study, the sustainability, and challenges of integrating a nutrient recovery system for localised production of fertilisers were assessed through the installation of a nutrient recovery batch reactor at a local operating farm, where the produced fertiliser would be applied. The study involves four major processes: septage collection, hydrolysis, chemical precipitation, and farm application. The batch reactor installed was used to treat the raw septage and to recover a high value fertiliser through hydrolysis and chemical precipitation, respectively. The efficiency of the recovered phosphorus fertiliser (RPF) as a P-source fertiliser was also evaluated through its application for eggplant and tomato production. There is a lack of demonstration projects beyond laboratory-scale to evaluate the sustainability of existing technologies for nutrient recovery from wastewater feedstock. Through this study, the concept of circular P economy would be applied in real scenario to promote a paradigm shift to a resource-oriented sanitation system for sustainable communities in developing countries such as the Philippines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nutrient Recovery Batch Reactor

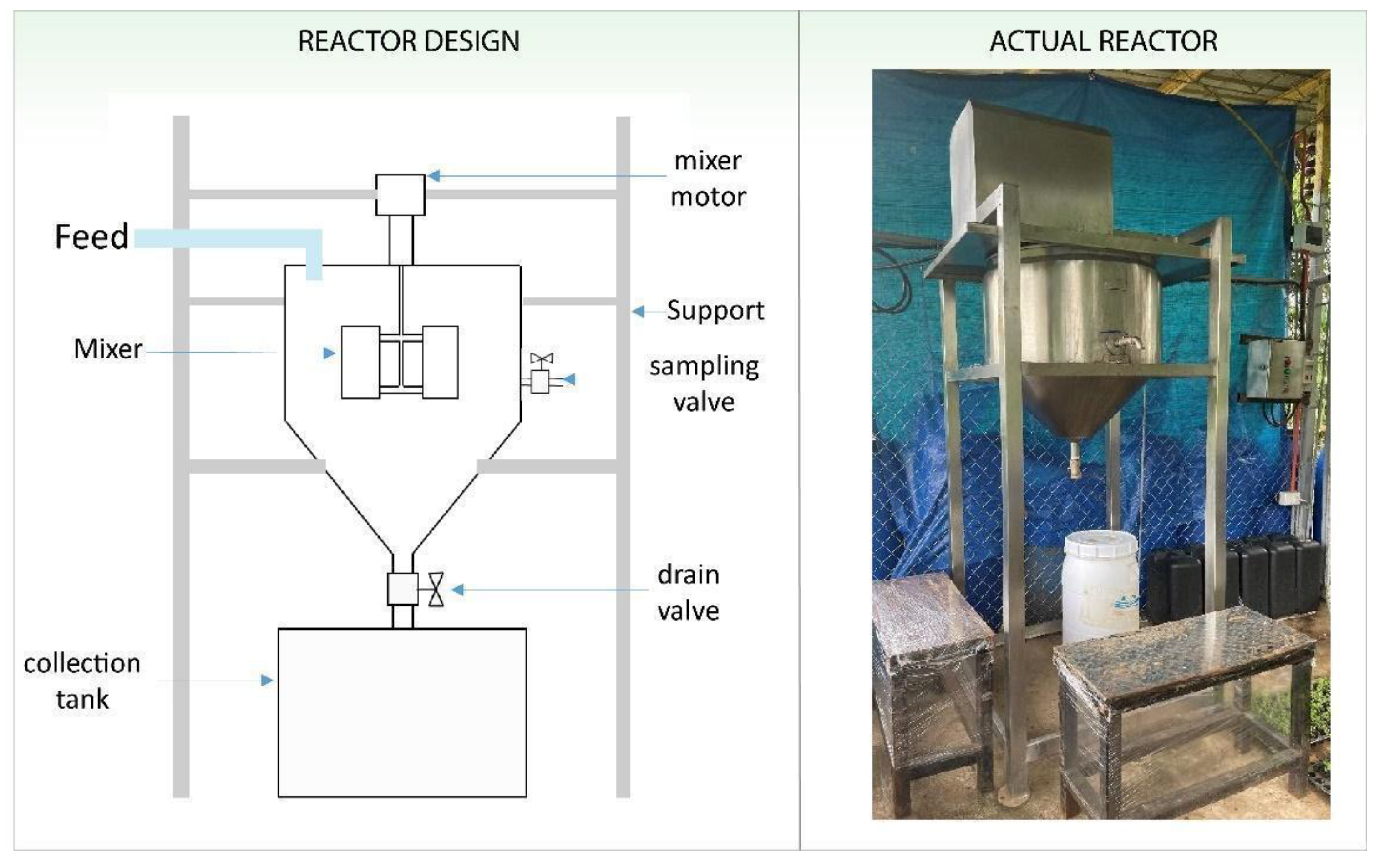

A fabricated batch reactor for the recovery of nutrients (i.e. phosphorus fertiliser) from septage was installed at Salikneta Farm (Salikneta), a 63 hectare-farm managed by a university located at Upper Ciudad Real, San Jose Del Monte, Bulacan (14°48'09.3"N 121°07'38.5"E). Various crops are being grown inside the farm such as tomatoes and eggplants, and livestock are being bred for research purposes and for local food distribution and consumption. The nutrient recovery batch reactor was designed with a maximum capacity of 100 L (0.10 m

3) per batch with an overall dimension of 0.762 m (L) x 0.762 m (W) x 1.859 m (H), shown in

Figure 1. Its conical tank with a diameter of 0.610 m and depth of 0.644 m is supported by a stand and frame. The reactor mixer has a motor drive (0.37 kW, 220/440V, 60Hz, 3-phase) and a variable frequency drive to adjust the mixer speed between 20.94 – 41.89 rad/s (0 - 60 Hz).

2.2. Septage Sources

The septage was collected from two different sources namely, the septic tanks at Salikneta farm and from a septage treatment plant (SpTP) in Metro Manila, to recover the required amount of fertiliser for farm application. The septic tanks at Salikneta and from a septage treatment plant (SpTP) were collected using a slurry pump. Salikneta has about 10 functional septic tanks with a cumulative capacity of 200 L. For the business-as-usual scenario, the septage is being hauled twice a year by a third party for desludging and septage treatment, thus accumulating an average of 400 L of septage every year. The SpTP, located 35 km from Salikneta, has an operational treatment capacity of 240 m

3/day (240,000 L/day) at 16 hrs/day operation, where the raw septage is typically hauled from residential buildings and houses within Metro Manila. Prior to the operation of the batch reactor, the liquid and solid components of each septage source were characterised and the analyses are shown in

Table 1.

The raw septage was characterised showing that it contains the basic components of a fertiliser such as phosphorus (P), nitrogen (N), and potassium (K). The solid component of septage from Salikneta has an average of 4,830 mg/kg of total phosphorus (TP), 10, 800 mg/kg of total nitrogen (TN), and 1,010 mg/kg of potassium (K), while the septage from the SpTP contains an average of 12,700 mg/kg TP, 15,700 mg/kg TN, and 780 mg/kg of K. The raw septage was also analysed to have 54,410 mg/L total solids. It is evident that both septage sources contain high concentrations of nutrients that could be potentially recovered. Consequently, the liquid component of septage from Salikneta only contains an average of 7.7 mg/L PO

4-P and 77 mg/L NH

4-N while the SpTP has 7.9 mg/L PO

4-P and 129 mg/L NH

4-N. This is lower than the required average soluble PO

4-P needed to economically precipitate struvite, that is 50 mg/L PO

4-P [

33]. Moreover, both septage sources have high amounts of micronutrients like calcium (Ca), iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), and zinc (Zn) which are usually bonded with phosphate ions [

34]. Hence, it would be difficult to apply the current nutrient recovery technologies directly without the pre-treatment of septage through hydrolysis, releasing P from the solid components into soluble form as phosphates.

Heavy metals were also analysed and showed to have very low concentrations to no detection of arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), copper (Cu), nickel (Ni), lead (Pb), and mercury (Hg). In addition, the raw septage also contains a high amount of microbiological components like fecal coliform and

Escherichia coli (

E. coli) which is expected based on the conventional parameters of septage characteristics reported by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) [

35], but these parameters could be reduced throughout the nutrient recovery process [

27].

2.3. Batch Reactor Operations

2.3.1. Hydrolysis of Septage

The first process in the batch reactor was hydrolysis for the pre-treatment of raw septage that releases the P and N from the solid component of the septage into soluble forms in the liquid component. The operating conditions for hydrolysis stage are summarised in

Table 2. The lower the pH the more phosphorus could be dissolved efficiently and the product is assumed to be generally pathogen-free [

31]. Hence, the septage was treated with 37% hydrochloric acid (HCl) gradually, to achieve the target pH of 2.0 under continuous mixing at 200 to 250 rpm (20 to 25 hz). After every addition of HCl, a 10-minute homogeneous mixing was performed, and samples were collected to measure the pH. When the target pH was achieved, hydrolysis continued for around 2 hours. Then the hydrolysed septage was drained into a settling drum. Settling was done for two to three days to separate the hydrolysed septage (i.e. supernatant) from the solid waste sludge. The solid waste sludge was transferred into the drying pan for air drying. The dried waste sludge was then characterised for its future use as soil conditioner. The hydrolysed septage was collected and transferred back to the batch reactor for the subsequent struvite precipitation process.

2.3.2. Recovery of Phosphorus Fertiliser

The recovery of phosphorus fertiliser was conducted in the batch reactor through chemical precipitation to promote struvite formation. The precipitation occurs at basic condition, thus the initial pH of the hydrolysed septage was first analysed to determine the amount of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) needed. The calculated amount of NaOH solution was poured into the batch reactor while being subjected to continuous mixing until pH 9.0 was achieved [

36]. The hydrolysed septage was analysed for phosphate and ammonium concentrations to determine the amount of magnesium chloride hexahydrate (MgCl

2·6H

2O) and ammonium chloride (NH

4Cl) needed to form struvite according to equation 1. However, the MgCl

2·6H

2O added is calculated based on the Mg:P molar ratio of 2:1, since it is recommended to apply a ratio higher than to that of the stoichiometric value of 1:1 [

37], while the NH

4Cl added is calculated based on the N:P molar ratio of 4:1 [

36]. The mixture was subjected to continuous mixing for one to two hours at 100 to 150 RPM (10-15 hz) for the struvite crystallisation process. Then the precipitates were left to settle at the conical bottom of the batch reactor for 18-24 hours. The settled precipitates at the bottom were flushed and transferred to drying pans subjected to air and sun drying. The dried precipitates were collected for characterisation. The recovered precipitates were used as recovered phosphorus fertiliser for farm application research. The remaining effluent from the batch reactor was also drained and stored in storage drums, and samples were analysed to identify the proper treatment process prior to application, such as an added water source for crop irrigation or hydroponics.

2.3.3. Batch Reactor Performance

The performance of the batch reactor was evaluated based on the material balance calculated throughout the process flows for every 100 L or raw septage processed. Thirty-eight batches were run, processing around of 3,682 L of raw septage from Salikneta and SpTP to produce 10,252 g of RPF for farm application studies [

38]. Thirty-one batches (batch numbers: 1-31) were done using the septage from SpTP and Salikneta with a ratio of 90:10, two batches were done using the septage from Salikneta farm (batch numbers: 32-33), and five batches was done using the septage from SpTP (batch numbers: 34-38). The batches were run to accommodate the required phosphorus fertiliser needed for the crop yield studies. To evaluate holistically the performance of the batch reactor in the context of circular economy, an overall material balance was calculated considering 1 batch or 100 L of raw septage processed from collection to recovery. The calculations are based on the analyses of raw septage, including septage density (1.006 kg/L) and total solids (54,410 mg/L), and characterisation of RPF, effluent, and waste sludge. Losses throughout the processes were also considered in the calculations, estimating 20% losses-to-septage ratio due to the attached water/ moisture and manual collection of intermediate products (i.e. wet waste sludge and wet precipitates) during the drying process. The efficiency of hydrolysis is evaluated as the amount of PO

4-P released shown in equation 2:

where [PO

4-P]

h is the PO

4-P concentration after hydrolysis and [PO

4-P]

sl is the initial PO

4-P concentration in the liquid component of the raw septage. The nutrient recovery efficiency in the form of RPF, is evaluated by the percent of PO

4-P recovered based on changes in PO

4-P concentration from the hydrolysed septage and the effluent shown in equation 3:

where [PO

4-P]

e is the concentration of PO

4-P in the effluent.

2.4. Application of the Recovered Phosphorus Fertiliser to Farm

Field experiments were conducted at Salikneta under greenhouse condition, to compare the growth and performance of eggplant (Calixto variety) and tomato (Diamante Max F1 variety) in response to the application of RPF and commercial fertiliser (ammonium phosphate). The application of fertiliser for every treatment in the experiments is based on the initial soil analysis of 80 kg N, 120 kg P2O5, 30 kg K2O and recommended rates for eggplant and tomato.

2.4.1. Field Experiments for Eggplant

Eggplants were planted in 12 m2 plots laid out in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replicates of four fertiliser treatments: control or no fertiliser application (E-T1); application of 16 g ammonium phosphate per plant (E-T2); application of 42 g RPF per plant (E-T3); and application of 21 g RPF and 8 g ammonium phosphate (E-T4).

The field plots were ploughed twice at a depth of 15-20 cm deep at a one-week interval, followed by harrowing to further break the soil peds into the desired soil tilth and level the field. Plastic mulch was placed over each plot and was fastened to the soil using 6-8 cm long bamboo slats placed 30 cm apart. Planting holes was distanced at 75 cm between columns and 50 cm between rows.

For seedling production, one to two seeds were placed in each hole of the holed seedling tray filled with soil growing media. The seedlings were watered regularly in the morning for soil moisture. Thinning was done 3-5 days after emergence, only the robust seedling was left in each hole. The seedlings were drenched weekly with urea solution (10 g of urea diluted in 1 gal of water) for one month. The seedlings were kept in the greenhouse for three-weeks and cared against weeds, pests, and diseases. Seedling hardening was done one week before transplanting. Twenty-eight eggplant seedlings were transplanted in each plot. Each seedling was gently pulled-out from the seedling tray and carefully transplanted into the prepared holes of each plot to avoid root-shoot injury. Re-planting of the missing hills was done three to five days after transplanting. During the dry season, the plants were watered thrice a week and during the wet season the eggplant was watered when soil was dry. The plants were strictly monitored against wilting through pruning and weeding.

The recommended rate of fertiliser applied to eggplants is 80-80-0. The first application of fertilisers was done 14 days after transplanting (DAT). A The second application with urea fertiliser was done 30 DAT. Urea was used for sufficing the nitrogen requirements and the calculated rate of 2.5 g, 6.5 g, and 5.0 g for E-T2, E-T3, and E-T4, respectively. Harvesting started two weeks after flowering and was done twice a week. The harvested eggplants are usually 8-10 cm long and should be soft.

2.4.2. Field Experiments for Tomato

Tomato grown in polyethylene bags was laid out in RCBD with four replicates of six fertiliser treatments: control or no fertiliser application (T-T1); NPK fertiliser (T-T2); RPF (T-T3); application of RPF and K (T-T4); ammonium phosphate (T-T5); and ammonium phosphate and K (T-T6).

Seeds were sown in a seedling tray with a planting medium having a ratio of 2:2:1 of compost, soil, and perlite. Seedlings were watered twice a day. Seedlings were hardened through full sunlight exposure for 10 days. Tomato seedlings was transplanted 30 days after sowing. Seedlings were then transferred in a 9 in x 16 in polyethylene bag with 20 kg of soil. Watering of the plants was done every other day to avoid waterlogging that may lead to development of diseases and even death of plants. Weeding was also done to avoid competition for water, space, and especially nutrients; and to reduce the possibility of the occurrence of pests and diseases. Trellising was also done 15 days after transplanting to provide support for the growing tomatoes.

Application of ammonium phosphate was done during transplanting. On the other hand, RPF was applied during planting and 14 days after transplanting using ring method. To supply plants their needed requirement for N and K, urea and muriate of potash was applied using split application at 15 and 30 days after transplanting, one-inch deep and 3 inches away from the base of the plant. Harvesting of tomato fruits was done at light red stage. The frequency of harvesting is twice a week early in the morning for five harvestings.

2.5. Analyses

The ammonia-nitrogen (NH3-N), orthophosphate-phosphorus (PO4-P), and nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N) of raw septage, hydrolysed septage, and effluent were analysed using a portable spectrophotometer (Digital Reactor 1900, HACH). The raw septage, effluent, and recovered phosphates were outsourced to accredited third-party laboratories for analyses of various parameters like wet chemistry (biological oxygen demand, chemical oxygen demand, NH3-N, PO4-P, NO3-N, total nitrogen, total phosphorous, potassium, total organic carbon, total suspended solids, calcium and magnesium), heavy metals (arsenic, cadmium, iron, mercury, lead, and zinc), and microbiology (E.coli and Fecal coliform). Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis (EDX), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis were conducted to identify the elemental composition and mineralogical phases of composite samples from the recovered P-fertiliser processed from the raw septage of Salikneta and SpTP.

For the application of fertilisers to tomato, titratable acidity (TA) was measured every after harvest following the standard procedure by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists [

39]; Total Soluble Solids (TSS) of tomato fruits were measured using refractometer; number of seeds per treatment was recorded; and yield per plant was measured every harvest. The data collected were subjected to Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) using SPSS 22 and Microsoft Excel data packages. Comparison among means was done using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) at 5% level of significance.

3. Results

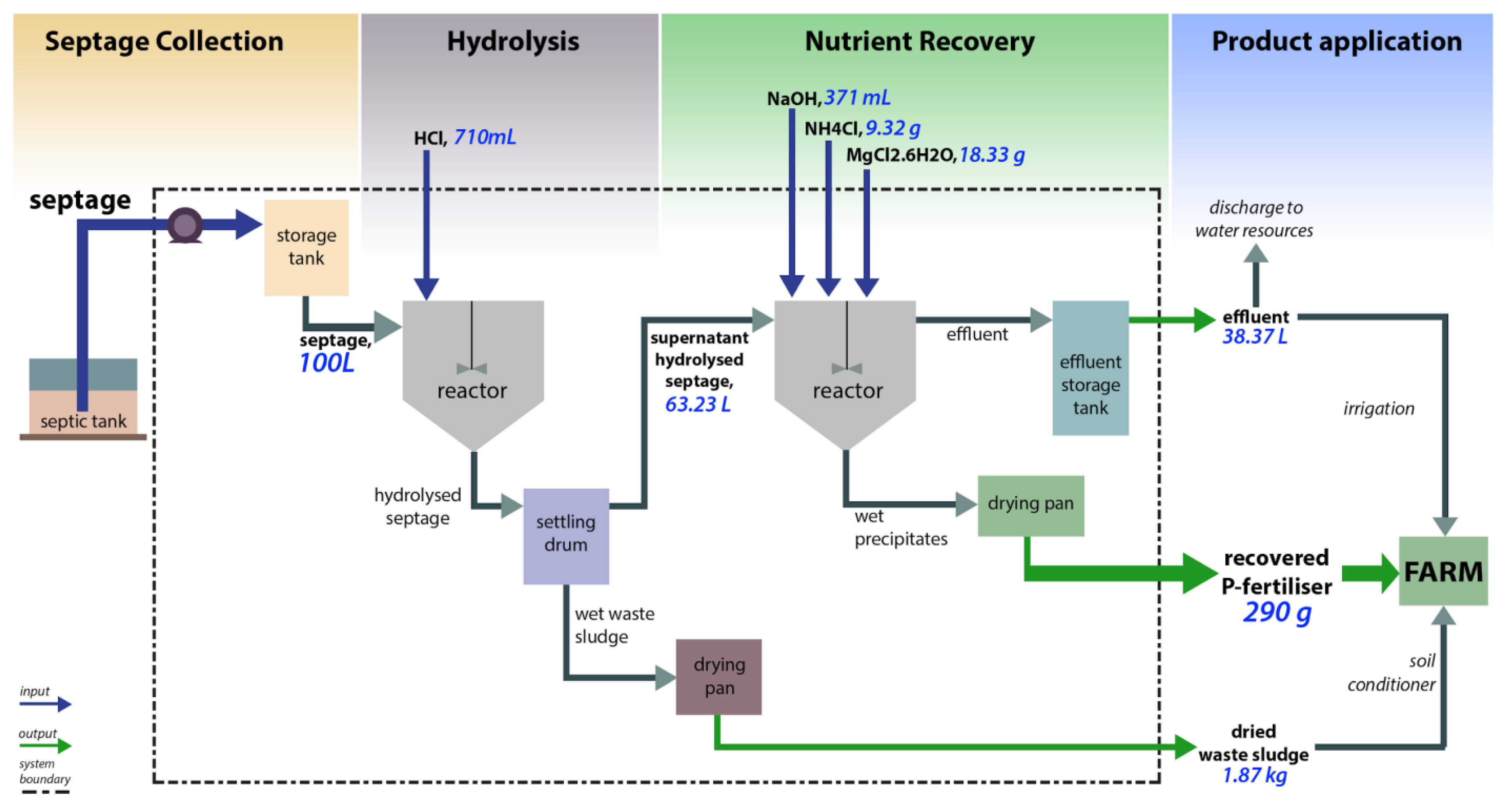

3.1. Process Flow and Material Balance

The performance of the nutrient recovery batch reactor was evaluated based on the movement of all the materials entering and leaving the identified system boundary as shown in

Figure 2. The whole production is divided into four major processes: septage collection, hydrolysis, nutrient recovery via chemical precipitation, and product application to farm for local crops (i.e. eggplant and tomato). With the basis of processing 100 L of raw septage, the material balance of raw materials, by-products, and the RPF was calculated. The material balance for every component of the raw materials, by-products, and RPF are presented in

Table A1. The detailed data and results of the material balance are presented in the

Supplemental Information (Table S1, Table S2, and Table S3). An average of 290 g of RPF for every 100 L of raw septage processed, or for every batch, was produced. Moreover, the whole system would produce 38.37 L of effluent and 1.87 kg of dried waste sludge as by-products.

3.1.1. Effect of Hydrolysis

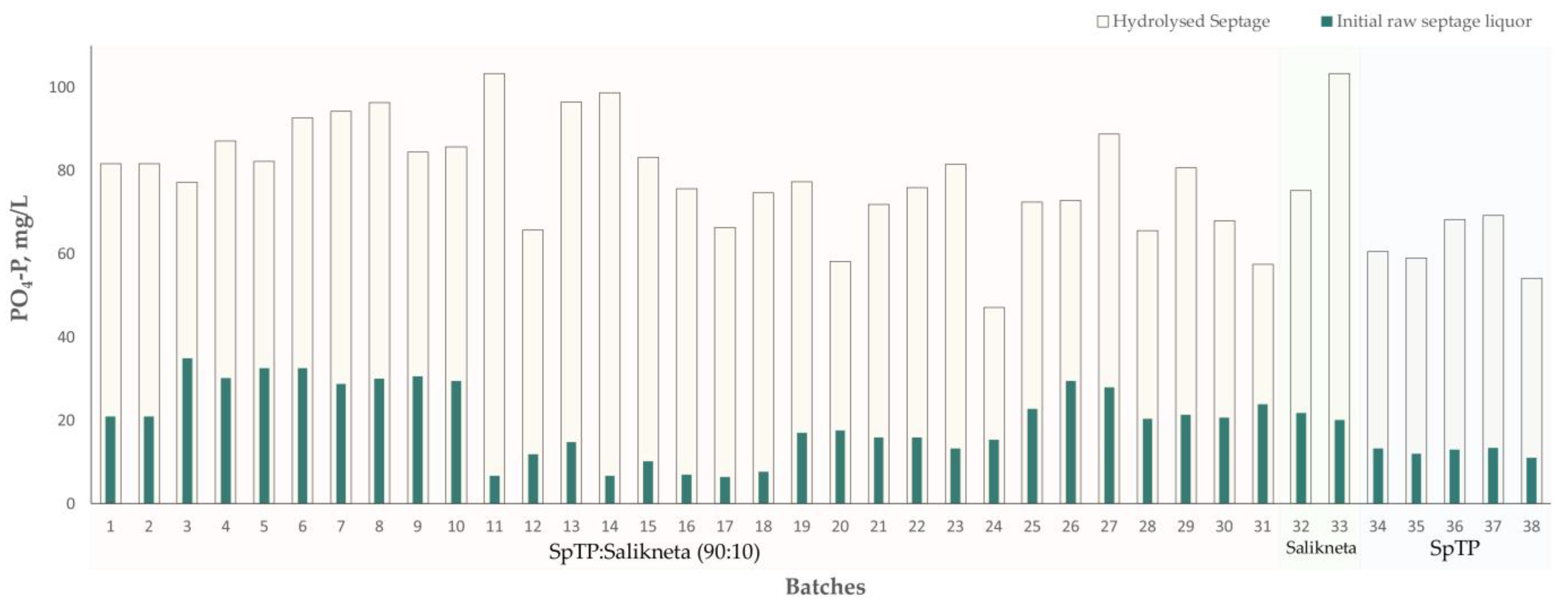

To maximise the recovery from the raw septage, hydrolysis was done as pre-treatment to increase the concentration of dissolved phosphates needed for struvite precipitation.

Figure 3 shows the trend of phosphates initially present in the raw septage liquor and the total concentration of phosphates after hydrolysis (i.e. hydrolysed septage), for every batch. The initial raw septage liquor has an average of 17.84±4.62mg/L PO

4-P. After hydrolysis, the phosphate concentration of the supernatant or the hydrolysed septage increased to an average of 76.74±13.63 mg/L PO

4-P. Hence, the pre-treatment managed to release about 58.90±9.33 mg/L PO

4-P from the septage sludge, that is 77% of the total phosphate concentration in the hydrolysed septage (details in

Table A2). The fluctuation of results observed in

Figure 3 reflects the varying characteristics of each batch of raw septage processed which mainly depends on the source and type of septic tank, especially for the septage collected from the SpTP. Generally, lower pH could dissolve more phosphorus but in actual scenarios, the phosphorus dissolution rate varies due to the presence of different phosphorus compounds in various types of wastewater sludge [

31].

3.2. Recovered Phosphate Fertiliser (RPF)

For struvite precipitation using the batch reactor, an average of 98.50% was recovered from the hydrolysed septage as phosphate fertiliser leaving an effluent that passed the regulatory standards as shown in

Table A1. The phosphates were successfully recovered as phosphate fertilisers with characteristics shown in

Table 3. Based from the definition given by the Philippine government through the Fertilizer and Pesticides Authority (FPA), the RPF can either be classified as: non-traditional inorganic fertiliser wherein the major nutrients (i.e. NPK) are supplied by synthetic or chemical compounds; or a fortified organic fertiliser defined as any decomposed organic product of plant or animal origin is enriched with chemical ingredients to increase its nutrient content to a minimum Total NPK of 8% [

40]. Thus, the characterisation results of the RPF are compared to both types of fertilisers. The recovered precipitates contain 2,010 mg/kg TN, 32,900 mg/kg TP, and 2,400 mg/kg K, resulting in a total NPK of 8.03% by weight. The value of Total NPK is above the minimum limits by the Philippine National Standards (PNS) for Organic Fertilizer, hence the recovered precipitates can be qualified as a fertiliser [

41]. The precipitates also have high contents of micronutrients (Ca, Fe, Mg, Zn), that are supplemental for plant growth. Moreover, the

E.coli, fecal coliform, and heavy metals are of lower values than the standards set by the FPA and the Association of American Plant Food Control Officials (AAPFCO) for inorganic fertilisers [

40,

42]. The subsequent analyses would discuss the quality and purity of struvite produced.

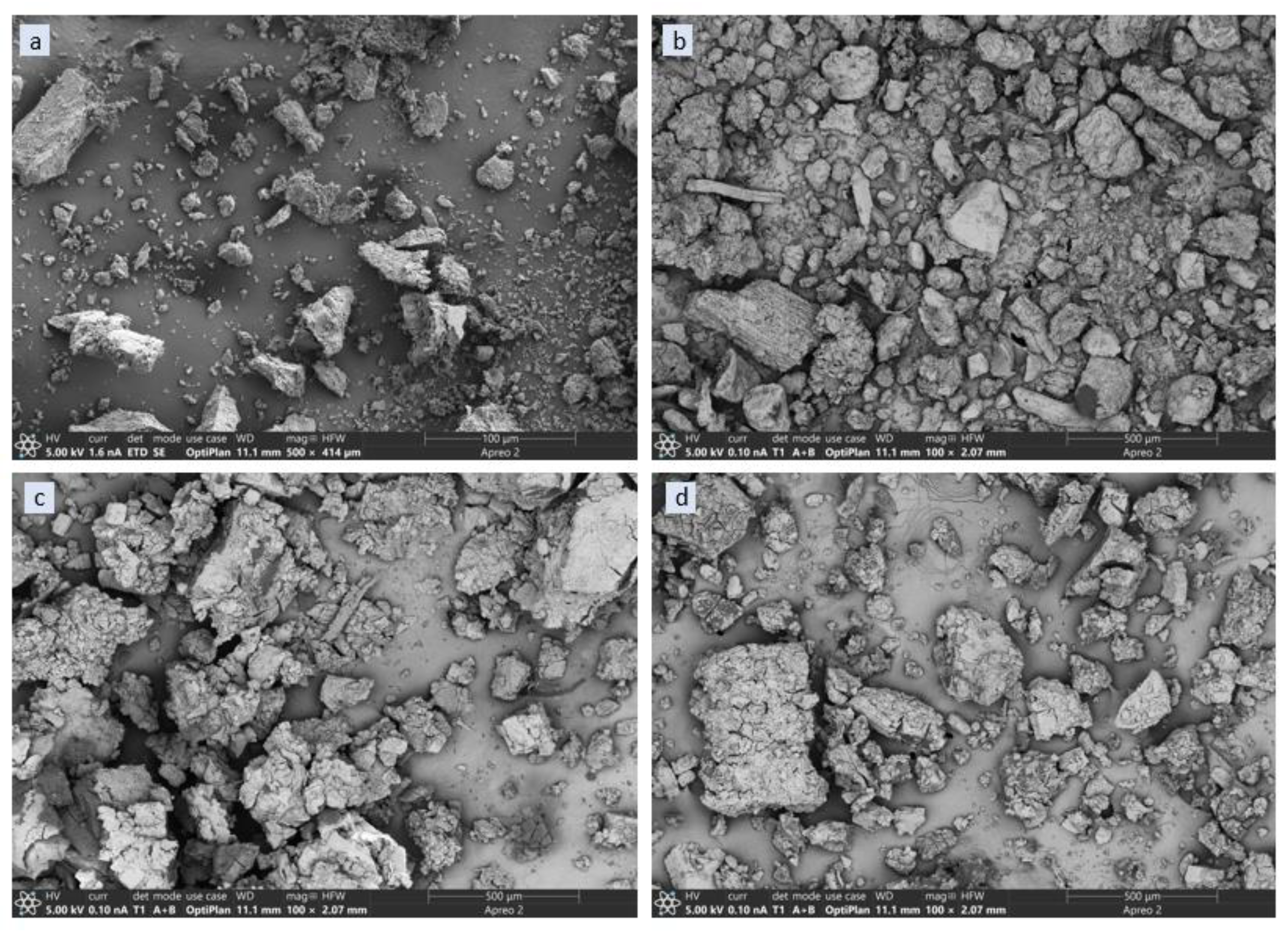

The Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images for the recovered precipitates and waste sludge showed various crystal shapes as shown in

Figure 4. The image for the commercial struvite fertiliser was observed to have more orthorhombic crystal shapes with lesser contamination of other compounds, as shown in

Figure 4a, while the image of waste sludge from the hydrolysis process (

Figure 2b) expectedly showed more heterogeneous shapes. It could also be observed that the images of RPF processed from the septage of Salikneta do not differ from the septage processed from the SpTP. There are some orthorhombic shapes that represents struvite, but there were other irregular course shapes that could be attributed to other phosphate precipitates such as amorphous calcium phosphates [

37], given that the initial concentration of calcium is relatively high in the raw septage (see

Table 1). Since the precipitates produced were not pure struvite, the term recovered phosphorus fertiliser (RPF) would better describe the main product as it can still be classified as fertiliser based on the characterisation results in

Table 3. Some studies utilising animal manure [

43] and municipal wastewater [

44], produced similar SEM images.

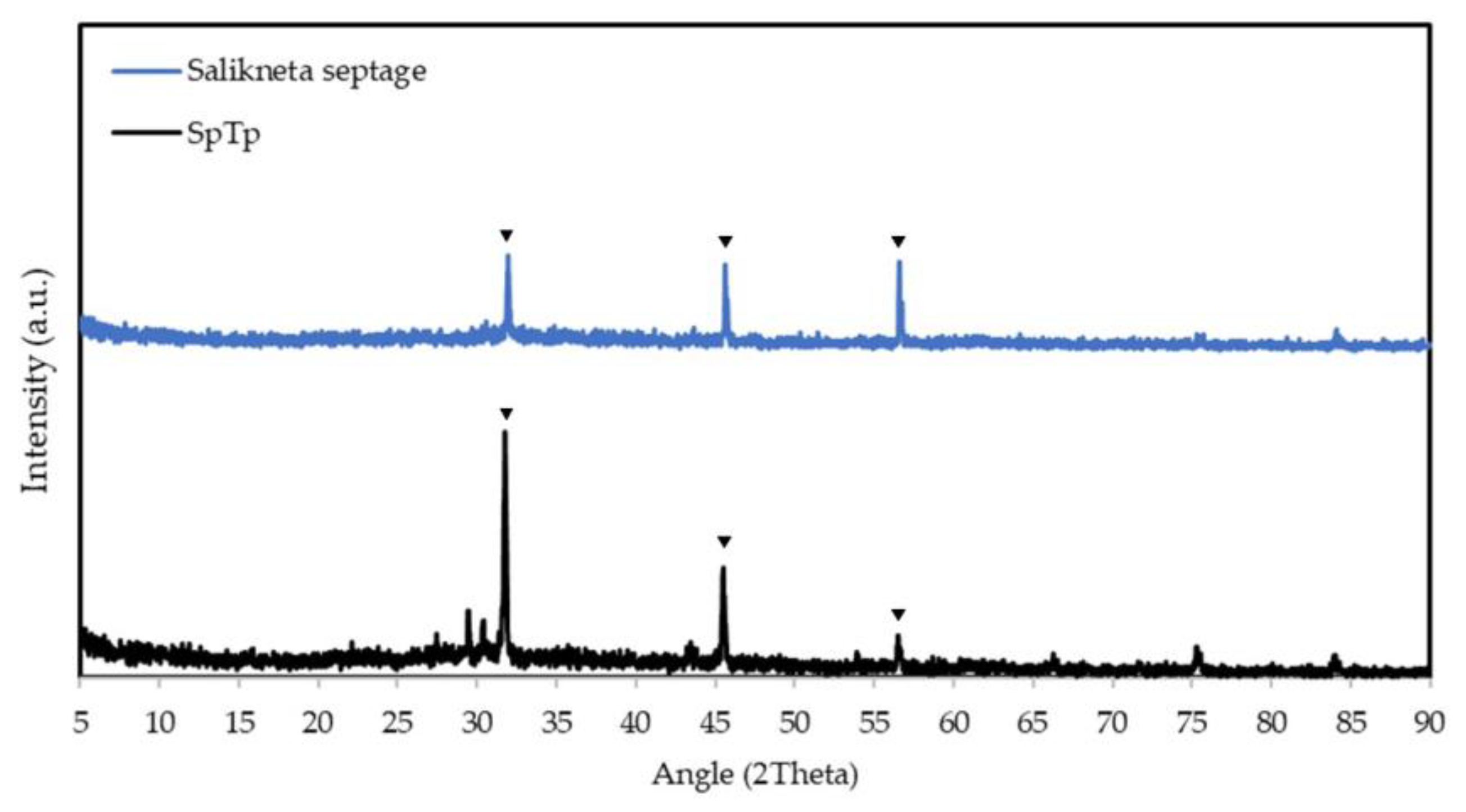

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis for the RPF from Salikneta and SpTP sludge are illustrated in

Figure 5a and

Figure 5b, respectively. The distinct peaks in both samples are observed at around 2Ө = 31, 45, and 56°. The peaks observed at 2Ө = 31.9372, 45.6552, and 56.6247° have almost similar intensities for the RPF from Salikneta sludge. On the other hand, the peak at 2Ө = 31.7463° had the highest intensity for the RPF from SpTP sludge. Comparing the results with the XRD analysis of struvite presented in the recent study of de Souza Meira et. al. [

45] and Sun et. al. [

29], it could be concluded that the samples contain other phosphate precipitates. The presence of other micronutrients may have affected the morphology and composition of the recovered fertilisers. The impact of the the micronutrients such as Ca

2+ and Al

3+ is explained in the study of Acelas et al. [

46], by investigating the struvite purity and morphology at varying Mg

2+:Ca

2+ and Mg

2+:Al

3+ molar ratios. The XRD analysis showed that the peaks for struvite crystals became less distinct at increasing concentrations of Ca

2+ and Al

3+.

Based on the SEM and XRD analyses, there is a need to further improve the operating conditions to achieve high quality and purity of struvite in the RPF. One possible solution is to reduce the presence of the other micronutrients such as calcium and iron in the hydrolysed samples but at the expense of higher production costs.

3.2.1. By-products

As shown in the process flow and material balance in

Figure 2, two by-products were produced, the wastewater effluent, and the dried waste sludge. The effluent is typically discharged in water bodies while the waste sludge is transported to landfills for disposal. However, in this study, both the effluent and the waste sludge were characterised, shown in

Table 5, to evaluate its potential as by-products of the proposed circular phosphorus economy application. The effluent characteristics passed the Philippine Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Administrative Order (DAO) 2016-08 and DAO 2021-19 General Fffluent Standard (GES) for Class C, shown in

Table 5, providing evidence that the batch reactor could efficiently treat the septage [

47,

48]. Moreover, this shows the effluent’s potential reuse as irrigation water in the farm, avoiding significant amount of water use and thus saving water costs. The dried waste sludge was also analysed and compared to US EPA standard for biosolids, as shown in

Table 5, to evaluate its potential as a by-product rather than as waste [

49]. Considering the characteristics of the raw septage processed, presented in

Table 1, the dried waste sludge was expected to contain minimal to no detection of heavy metals (i.e. As, Cd, Hg, and Pb), fecal coliform, and

E. coli; while having significant amounts of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK), and other nutrients (i.e. Ca, Fe, Mg, Zn), thus showing its potential as a soil conditioner or supplemental fertiliser for local farm crops.

3.3. Crop Yield

Field experiments were conducted to compare the growth and performance of eggplant and tomato in response to application of RPF and commercial fertiliser (i.e. ammonium phosphate). The results presented on

Table 6 show that differences in eggplant yields ranged from 9 to 11 tons compared with the yield from the control. It was found that the yields of treatments E-T3 and E-T4 containing RPF as phosphorus source do not have a significant difference with E-T2 containing commercial fertilisers. Hence, this research was able to demonstrate that eggplant fertilised with RPF and urea could have a comparable yield with eggplants fertilised with commercial fertilisers.

For the quality of tomato produced,

Table 7 presents that the highest titratable acidity (TA) of 5.82 was measured from T-T2, plants applied with NPK followed by T-T5, T-T6, T-T4, and T-T3. The study also shows that T-T2 had the highest recorded total soluble solids (TSS) but was comparable to T-T3, T-T4, T-T5, and T6 but statistically different to T-T1. It was found that potassium (K) has profound influence on fruit quality particularly size, appearance, colour, soluble solids, acidity, and vitamin contents thus TSS, and TA significantly increased with increasing rates of K [

50].

On the number of seeds, the study showed that amongst treatments T-T2 and T-T4 had the highest number of seeds followed by T-T3, T-T6, and T-T5. Statistical analysis shows that T-T2, T-T3, T-T4, T-T5, and T-T6 comparable but is statistically different from the T-T1. According to Xie et. al. [

51], addition of P fertiliser showed an increased seed yield of oilseed flax. Oloyede et. al. [

52], reported that in their study that application of NPK on pumpkin has significantly improved its seed yield.

The yield per plant was measured every harvest. The highest yield was obtained from T-T2 (1,870 g) followed by T-T6, T-T5, T-T4, and T-T3. This result can be attributed to the nutrients supplied to the plants. T-T2 received complete and high nutrient content of N, P, and K. However, statistically T-T3, T-T5 and T-T6 yields were comparable to T-T2. The lowest yield was still obtained from T-T1 with no fertiliser application. In general, the improved vegetative growth, yield and chemical content of tomatoes was attributed to the received complete NPK nutrients.

The RPF produced from the nutrient recovery reactor contained significant amounts of P and N required for crop growth, but the P in the RPF is not just in struvite form but other phosphates were also formed based on the SEM results (see

Figure 4). However, the crops fertilised with RPF managed to produce comparable yields with crops fertilised with commercial and conventional fertilisers. Previous studies have reported that utilising pure struvite is not agronomically viable but when blended with other phosphate fertilisers, it could maintain crop yields that are comparable to conventional P fertilisers [

15,

46].

4. Discussion

The potential of integrating a local nutrient recovery system for onsite sanitation systems to create a paradigm shift from the business-as-usual scenario of linear P pathway to circular economy was exhibited and evaluated. Hence, resulting in a sustainable management of waste and resources within a community. Circular P economy considers sustainability wherein socio-economic, and material aspects are integrated into the circular pathway of P systems management [

54]. Ultimately, circular P economy utilises nutrient recovery systems to divert P flows before reaching the water resources back to agri-food systems, while by-passing further extraction of fossilised P [

9].

Figure 6 generally compares the value and supply chains involved for both linear P pathway and circular P economy flows.

For nutrient recovery systems, the processes and technologies are being constantly developed and optimised. However, there is a lack of demonstration projects beyond the laboratory-scale and application to real scenarios while considering most, if not all, of the value and supply chains in the circular economy [

55]. In this real-case study, waste feedstock (i.e. septage) from farm-school community and treatment facility was processed and converted to a high value product (i.e. RPF) while the by-products (i.e. effluent and waste sludge), typically considered as waste, could potentially be recycled for other purpose within the circular flow. Result shows a favourable recovery of P from waste for the local effluent standard however, economic production of RPF should be further investigated and improved. Additionally, the application and use of the RPF were evaluated for the local production of crops for food. Results show that the yields for both eggplants and tomatoes are comparable to that of crops grown using commercial fertilisers. This shows the potential of recovered fertiliser as an alternative for local farmers being affected by the exponential increase of fertiliser prices. This study shows that septage management could be turned into a circular economy industry that the local government and community could support and do to reduce environmental pollution and improve food production without heavy reliance on fertiliser importation.

Stakeholder engagements through workshops and focus group discussions were done to understand challenges in the implementation of a nutrient recovery system in the Philippines [

38]. The farmers, in particular, gave positive perspective of the system as it produces a high value product that could be used locally in their crops, however, their main issue is their technical capacity for the whole production process. Furthermore, acceptability of fertiliser obtained from human waste will have more social acceptability as compared to the direct application of human waste for food production. Indeed, social impacts are important for sustainable development through involvement of potential users to improve marketability of the product while minimising the complexity of the technology [

20]. Hence, there is a high potential to apply the circular phosphorus economy concept in a localised setting for sustainable sanitation and sustainable management of resources and wastes in vulnerable areas.

Further research is needed to be done to assess and quantify the avoided environmental impacts due to the application of circular P economy (nutrient recovery system in a localised setting), addressing current challenges in sanitation, waste management, and phosphorus resource depletion. Sustainability assessment tools could be applied, such as life cycle sustainability assessment or multi-criteria decision-making analyses, to assess and quantify the socio-economic impacts holistically for all value and supply chains within the circular economy scope. This will further address the challenges on agri-food sector such as the increase in prices for fertiliser and thus food, eventually increasing poverty; and will provide support for policies to improve the local socio-economic endeavours for sustainable development programmes.

5. Conclusions

This study involves local production of recovered fertiliser and its application to the local farm, thus it provides a clear understanding of the potential and challenges brought about by the system in promoting resource-oriented sanitation system for sustainability, especially in developing countries such as the Philippines. The overall nutrient recovery process using the batch reactor could produce an average of 290 g of recovered phosphorus fertiliser (RPF) for every 100 L of raw septage processed. The acid hydrolysis of raw septage could increase the soluble phosphate concentration to 76.74±13.63 mg/L PO4-P (supernatant of the hydrolysed septage) from 17.84±4.62mg/L PO4-P (the initial concentration of the raw septage liquor). As the result of hydrolysis, about 77% of the phosphate concentration of hydrolysed septage comes from the released phosphates from the solid component of the raw septage. The chemical precipitation resulted to about 98.5% of phosphate being recovered as fertiliser from the hydrolysed septage. The two by-products of the system, effluent and waste sludge, was characterised as safe for discharge to water bodies and for disposal to landfills, respectively. Moreover, the effluent could be used as irrigation water for the crops in the farm and the waste sludge could be used as soil conditioner or supplemental fertiliser based on its characteristics. Consequently, the RPF was applied to eggplant and tomatoes having comparable yields with commercial fertilisers. Having an onsite nutrient recovery batch reactor could incur savings for both septage desludging and fertiliser costs, helping farmers and the local community. This shows the success of the proof-of-concept research on the application of the circular economy concept in a local setting through utilisation of local waste feedstock such as septage to produce a high value product such as the fertiliser; and the conversion of process wastes to by-products (i.e. effluent and waste sludge). Though further assessments are needed as social and economic factors are equally important for the sustainable development. In general, this research actualised the proof-of-concept of the circular phosphorus economy towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals identified by the United Nations, particularly zero hunger (goal 2), clean water and sanitation (goal 6), sustainable cities and communities (goal 11), and responsible consumption and production (goal 12), to improve the planetary health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Material balance for raw materials and intermediate products for every 100 L of raw septage processed (1 batch process); Table S2: Material balance for recovered phosphorus fertiliser and by-products for every 100 L of raw septage processed (1 batch process); Table S3: Ratio of raw materials, by-products, and recovered phosphorus fertiliser per L of septage; Figure S1: Fabricated nutrient recovery batch reactor installed at Salikneta Farm; Figure S2: Tomato and eggplant cultivated using the recovered phosphorus fertiliser from septage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S.; methodology, C.M.P, D.S., M.A.P. and M.E.A.S.; validation, D.S. and M.A.P.; formal analysis, M.A.P., C.M.P, R.D., A.O., A.B., and M.E.A.S.; investigation, A.L., C.M.P., R.D., A.O., A.B., M.E.A.S., M.A.P. and D.S.; resources, D.S., M.A.P., C.M.P., R.D., A.L., A.O., A.B., and M.E.A.S.; data curation, A.L., C.M.P. and M.A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.P.; writing—review and editing, C.M.P., A.B., D.S., M.A.P., R.D., A.L., A.O., and M.E.A.S.; visualization, C.M.P.; supervision, D.S. and M.A.P.; project administration, D.S., M.A.P. and C.M.P; funding acquisition, D.S. and M.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the following funding agencies: The UK BEIS funded Newton Prize (UK Newton Fund Grant Reference NP2PB\100028) for UK-Philippines research excellence; EPSRC supported Newton fund project (EP/P018513/1) "Water - Energy - Nutrient Nexus in the Cities of the Future"; Newton-Agham Fund PhD (grant number 537006268) was funded by the British Council and Department of Science and Technology-Philippines.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Salikneta Farm of Agri-vet Sciences Institute, De La Salle Araneta University for the support in operations and monitoring of the pilot-scale reactor throughout the duration of the research. The authors would also like to thank the Society for the Conservation of Philippine Wetlands, Inc. (SCPW) for their support and assistance in engaging the surrounding communities and other relevant stakeholders for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Material balance for every component of the raw materials, by-product, and product.

Table A1.

Material balance for every component of the raw materials, by-product, and product.

| Material Balance |

Raw materials |

By-product |

Product |

Raw

Septage |

37% HCl |

8.35 M NaOH |

MgCl2.6H2O |

NH4Cl |

Wastesludge |

Effluent |

Recovered phosphorus fertiliser |

| Volume, L |

100.00 |

0.71 |

0.37 |

- |

- |

- |

38.37 |

- |

| Mass, kg |

100.60 |

0.85 |

0.48 |

0.018 |

0.009 |

1.87 |

38.37 |

0.29 |

| NPK |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total Nitrogen, g |

101.72 |

- |

- |

- |

2.39 |

28.56 |

4.76 |

0.59 |

| Total Phosphorous, g |

69.89 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9.61 |

0.00 |

9.61 |

| Potassium, g |

49.31 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1.01 |

1.15 |

0.71 |

| Calcium, g |

172.41 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

11.67 |

60.24 |

22.03 |

| Magnesium, g |

19.97 |

- |

- |

2.15 |

- |

2.91 |

2.95 |

4.53 |

| Heavy Metals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Arsenic, g |

0.03 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.01 |

0.00 |

ND |

| Cadmium, g |

0.04 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.01 |

<0.001 |

0.00 |

| Iron, g |

135.71 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

23.52 |

0.00 |

12.80 |

| Mercury, g |

<0.0002 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

<0.0002 |

<0.0002 |

<0.0002 |

| Lead, g |

0.63 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.19 |

<0.005 |

0.01 |

| Zinc, g |

16.27 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4.31 |

0.00 |

0.15 |

| Fecal Coliform, MPN/100mL |

9.20x105

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.21 |

2.00 |

0.25 |

| E.coli, MPN/100mL |

9.20 x105

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.21 |

2.00 |

0.25 |

Table A2.

Phosphates released via hydrolysis of raw septage and percent phosphate recovered.

Table A2.

Phosphates released via hydrolysis of raw septage and percent phosphate recovered.

| Batch |

Raw Septage,

PO4-P, mg/L |

Hydrolysed septage,

PO4-P, mg/L |

PO4-P released,

PO4-P, mg/L |

% of phosphate released |

Effluent,

PO4-P, mg/L |

% PO4-P Recovered |

| SpTP:Salikneta (90:10) |

| 1 |

20.90 |

81.60 |

60.70 |

74.39 |

1.03 |

98.74 |

| 2 |

20.90 |

81.60 |

60.70 |

74.39 |

1.03 |

98.74 |

| 3 |

34.85 |

77.17 |

42.32 |

54.84 |

4.36 |

94.35 |

| 4 |

30.19 |

87.12 |

56.93 |

65.35 |

4.36 |

95.00 |

| 5 |

32.52 |

82.14 |

49.62 |

60.41 |

6.14 |

92.53 |

| 6 |

32.52 |

92.63 |

60.11 |

64.89 |

6.14 |

93.37 |

| 7 |

28.77 |

94.15 |

65.38 |

69.44 |

0.61 |

99.35 |

| 8 |

30.03 |

96.28 |

66.26 |

68.81 |

0.61 |

99.37 |

| 9 |

30.54 |

84.45 |

53.92 |

63.84 |

0.41 |

99.51 |

| 10 |

29.49 |

85.64 |

56.15 |

65.56 |

0.41 |

99.52 |

| 11 |

6.62 |

103.22 |

96.60 |

93.59 |

0.38 |

99.63 |

| 12 |

11.84 |

65.65 |

53.81 |

81.96 |

0.38 |

99.42 |

| 13 |

14.79 |

96.45 |

81.66 |

84.66 |

0.49 |

99.49 |

| 14 |

6.71 |

98.71 |

91.99 |

93.20 |

0.49 |

99.50 |

| 15 |

10.16 |

83.12 |

72.95 |

87.77 |

0.43 |

99.49 |

| 16 |

6.96 |

75.56 |

68.60 |

90.79 |

0.43 |

99.44 |

| 17 |

6.39 |

66.24 |

59.85 |

90.35 |

0.32 |

99.51 |

| 18 |

7.63 |

74.59 |

66.95 |

89.77 |

0.32 |

99.57 |

| 19 |

17.02 |

77.28 |

60.25 |

77.97 |

0.46 |

99.41 |

| 20 |

17.53 |

58.11 |

40.58 |

69.83 |

0.46 |

99.21 |

| 21 |

15.90 |

71.77 |

55.87 |

77.84 |

0.37 |

99.48 |

| 22 |

15.90 |

75.83 |

59.93 |

79.03 |

0.37 |

99.51 |

| 23 |

13.30 |

81.47 |

68.17 |

83.67 |

0.33 |

99.59 |

| 24 |

15.33 |

47.08 |

31.75 |

67.43 |

0.33 |

99.29 |

| 25 |

22.78 |

72.43 |

49.65 |

68.55 |

1.39 |

98.08 |

| 26 |

29.42 |

72.80 |

43.38 |

59.59 |

1.39 |

98.09 |

| 27 |

27.85 |

88.69 |

60.84 |

68.60 |

1.31 |

98.53 |

| 28 |

20.41 |

65.49 |

45.08 |

68.83 |

1.31 |

98.00 |

| 29 |

21.36 |

80.60 |

59.24 |

73.50 |

0.74 |

99.08 |

| 30 |

20.70 |

67.98 |

47.28 |

69.55 |

0.74 |

98.91 |

| 31 |

23.87 |

57.38 |

33.51 |

58.40 |

1.01 |

98.23 |

| Average |

20.10±8.87 |

78.81±12.94 |

58.71±14.59 |

74.09±10.98 |

1.24±1.64 |

98.45±1.91 |

| Salikneta farm |

| 32 |

21.70 |

75.23 |

53.53 |

71.15 |

0.53 |

99.29 |

| 33 |

20.09 |

103.22 |

83.13 |

80.53 |

0.53 |

99.48 |

| Average |

20.90±1.14 |

89.23±19.79 |

68.33±20.93 |

75.84±6.53 |

0.53±0.00 |

99.39±0.14 |

| SpTP |

| 34 |

13.24 |

60.57 |

47.33 |

78.14 |

1.73 |

97.15 |

| 35 |

12.02 |

58.95 |

46.94 |

79.62 |

1.73 |

97.07 |

| 36 |

12.91 |

68.20 |

55.30 |

81.08 |

1.57 |

97.69 |

| 37 |

13.44 |

69.19 |

55.75 |

80.58 |

1.57 |

97.73 |

| 38 |

11.00 |

54.06 |

43.06 |

79.65 |

0.90 |

98.34 |

| Average |

12.52±1.01 |

62.20±6.41 |

49.67±5.60 |

79.81±1.12 |

1.50±0.35 |

97.60±0.51 |

| Total Average |

17.84±4.62 |

76.74±13.63 |

58.90±9.33 |

76.58±2.93 |

1.09±0.50 |

98.48±0.90 |

References

- Cordell, D.; Drangert, J.O.; White, S. The Story of Phosphorus: Global Food Security and Food for Thought. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.; Zhang, Q. Energy-Nutrients-Water Nexus: Integrated Resource Recovery in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. J. Environ. Manage. 2013, 127, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerten, D.; Heck, V.; Jägermeyr, J.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Fetzer, I.; Jalava, M.; Kummu, M.; Lucht, W.; Rockström, J.; Schaphoff, S.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Feeding Ten Billion People Is Possible within Four Terrestrial Planetary Boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smol, M.; Preisner, M.; Bianchini, A.; Rossi, J.; Hermann, L.; Schaaf, T.; Kruopiene, J.; Pamakštys, K.; Klavins, M.; Ozola-Davidane, R.; Kalnina, D.; Strade, E.; Voronova, V.; Pachel, K.; Yang, X.; Steenari, B.M.; Svanström, M. Strategies for Sustainable and Circular Management of Phosphorus in the Baltic Sea Region: The Holistic Approach of the InPhos Project. Sustain. 2020, 12, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotto, L.P.A.; Beusen, A.H.W.; Villanoy, C.L.; Bouwman, L.F.; Jacinto, G.S. Nutrient Load Estimates for Manila Bay, Philippines Using Population Data. Ocean Sci. J. 2015, 50, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltazar, D.E.; Harada, H.; Fujii, S.; Tan, M.F.; Akib, S. A Comparative Analysis of Septage Management in Five Cities in the Philippines. Eng 2021, 2, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquet, K.; Järnberg, L.; Rosemarin, A.; Macura, B. Identifying Barriers and Opportunities for a Circular Phosphorus Economy in the Baltic Sea Region. Water Res. 2020, 171, 115433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, P.J.A.; Elser, J.J.; Hilton, J.; Ohtake, H.; Schipper, W.J.; Van Dijk, K.C. Greening the Global Phosphorus Cycle: How Green Chemistry Can Help Achieve Planetary P Sustainability. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 2087–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, P.J.A. Closing the Phosphorus Cycle. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 1001–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Liang, S. Nutrient Recovery from Wastewater: From Technology to Economy. Bioresour. Technol. Reports 2020, 11, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichy, B.; Kużdżał, E.; Krztoń, H. Phosphorus Recovery from Acidic Wastewater by Hydroxyapatite Precipitation. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 232, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, K.; Cordell, D.; Mavinic, D. A Brief History of Phosphorus: From the Philosopher’s Stone to Nutrient Recovery and Reuse. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batstone, D.J.; Hülsen, T.; Mehta, C.M.; Keller, J. Platforms for Energy and Nutrient Recovery from Domestic Wastewater: A Review. Chemosphere 2015, 140, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, S.A.; Doyle, J.D. Struvite Formation, Control and Recovery. Water Res. 2002, 36, 3925–3940. [Google Scholar]

- Talboys, P.J.; Heppell, J.; Roose, T.; Healey, J.R.; Jones, D.L.; Withers, P.J.A. Struvite: A Slow-Release Fertiliser for Sustainable Phosphorus Management? Plant Soil 2016, 401, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcas-Pilz, V.; Parada, F.; Villalba, G.; Rufí-Salis, M.; Rosell-Melé, A.; Gabarrell Durany, X. Improving the Fertigation of Soilless Urban Vertical Agriculture Through the Combination of Struvite and Rhizobia Inoculation in Phaseolus Vulgaris. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, C.; Fernández, B.; Molina, F.; Camargo-Valero, M.A.; Peláez, C. The Determination of Fertiliser Quality of the Formed Struvite from a WWTP. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 3041–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, S.F.; Giroto, A.S.; Dombinov, V.; Robles-Aguilar, A.A.; Jablonowski, N.D.; Ribeiro, C. Struvite-Based Composites for Slow-Release Fertilization: A Case Study in Sand. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ponce, R.; López-de-Sá, E.G.; Plaza, C. Lettuce Response to Phosphorus Fertilization with Struvite Recovered from Municipal Wastewater. HortScience 2009, 44, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaddel, S.; Bakhtiary-Davijany, H.; Kabbe, C.; Dadgar, F.; Østerhus, S.W. Sustainable Sewage Sludge Management: From Current Practices to Emerging Nutrient Recovery Technologies. Sustain. 2019, 11, 3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, E.; Atwater, J.; Mavinic, D. Recovery of Struvite from Stored Human Urine. Environ. Technol. 2008, 29, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignacio, J.J.; Malenab, R.A.; Pausta, C.M.; Beltran, A.; Belo, L.; Tanhueco, R.M.; Promentilla, M.A.; Orbecido, A. A Perception Study of an Integrated Water System Project in a Water Scarce Community in the Philippines. Water (Switzerland) 2019, 11, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, R.; Ward, B.J.; Strande, L.; Maurer, M. Review of Synthetic Human Faeces and Faecal Sludge for Sanitation and Wastewater Research. Water Res. 2018, 132, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Ofori-Amanfo, D.; Awuah, E.; Cobbold, F. A Comprehensive Study on the Physicochemical Characteristics of Faecal Sludge in Greater Accra Region and Analysis of Its Potential Use as Feedstock for Green Energy. J. Renew. Energy 2019, 2019, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaff, M.S.; Temmink, H.; Zeeman, G.; Buisman, C.J.N. Energy and Phosphorus Recovery from Black Water. Water Sci. Technol. 2011, 63, 2759–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGaughy, K.; Reza, M.T. Recovery of Macro and Micro-Nutrients by Hydrothermal Carbonization of Septage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 1854–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell, K.; Ruijter, F.J. d.; Kuntke, P.; Graaff, M. de; Smit, A.L. Safety and Effectiveness of Struvite from Black Water and Urine as a Phosphorus Fertilizer. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 3, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moges, M.E.; Todt, D.; Heistad, A. Treatment of Source-Separated Blackwater: A Decentralized Strategy for Nutrient Recovery towards a Circular Economy. Water (Switzerland) 2018, 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Mohammed, A.N.; Liu, Y. Phosphorus Recovery from Source-Diverted Blackwater through Struvite Precipitation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatziconstantinou, G.J.; Yannakopoulos, P.; Andreadakis, A. Primary Sludge Hydrolysis for Biological Nutrient Removal. Water Sci. Technol. 1996, 34, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antakyali, D.; Meyer, C.; Preyl, V.; Maier, W.; Steinmetz, H. Large-Scale Application of Nutrient Recovery from Digested Sludge as Struvite. Water Pract. Technol. 2013, 8, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y. Recovery of Phosphorus and Nitrogen from Alkaline Hydrolysis Supernatant of Excess Sludge by Magnesium Ammonium Phosphate. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 166, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornel, P.; Schaum, C. Phosphorus Recovery from Wastewater: Needs, Technologies and Costs. Water Sci. Technol. 2009, 59, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, K.P.; Pagilla, K.R. Reclaimed Phosphorus Commodity Reserve from Water Resource Recovery Facilities—A Strategic Regional Concept towards Phosphorus Recovery. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Guide to Septage Treatment and Disposal Guide to Septage Treatment Disposal; 1994. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-11/documents/guide-septage-treatment-disposal.pdf.

- Goel, S.; Kansal, A. Phosphorous Recovery from Septic Tank Liquor: Optimal Conditions and Effect of Tapered Velocity Gradient. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 124056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, A.; Limonti, C.; Curcio, G.M.; Molinari, R. Advances in Struvite Precipitation Technologies for Nutrients Removal and Recovery from Aqueous Waste and Wastewater. Sustain. 2020, 12, 7538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promentilla, M.A.B.; Longos, A.L.; Orbecido, A.H.; Suplido, M.E.A.A.; Rosales, E.M.E.; Pausta, C.M.J.; Damalerio, R.G.; Lecciones, A.J.M.; Devanadera, M.C.E.; Saroj, D.P. Nutrient Recycling from Septage Toward a Green Circular Bioeconomy: A Case Study in Salikneta Farm, Philippines. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 94, 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.G.; Jaiswal, P.; Jha, S.N. Non-Destructive Quality Evaluation of Intact Tomato Using VIS-NIR Spectroscopy Related Papers Non-Destructive Quality Evaluation of Intact Tomato Using VIS-NIR Spectroscopy. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 632–639. [Google Scholar]

- Fertilizer and Regulations Division. Fertilizer Regulatory Policies and Implementing Guidelines; Fertilizer and Pesticide Authority: Quezon City, 2019.

- Bureau of Product Standards. Philippine National Standard for Organic Fertilizer; 2014. http://spsissuances.da.gov.ph/attachments/article/1106/PNS-BAFS40-2014-OrganicFertilizer.pdf.

- Association of American Plant Food Control Officials. Statement of Uniform Interpretation and Policy (SUIP) #25 - The ‘Heavy Metal Rule’; 2019. https://www.aapfco.org/rules.html.

- Rahman, M.M.; Liu, Y.; Kwag, J.-H.; Ra, C. Recovery of Struvite from Animal Wastewater and Its Nutrient Leaching Loss in Soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 186, 2026–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavhungu, A.; Masindi, V.; Foteinis, S.; Mbaya, R.; Tekere, M.; Kortidis, I.; Chatzisymeon, E. Advocating Circular Economy in Wastewater Treatment: Struvite Formation and Drinking Water Reclamation from Real Municipal Effluents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira, R.C. de S.; Paz, S.P.A. da; Corrêa, J.A.M. XRD-Rietveld Analysis as a Tool for Monitoring Struvite Analog Precipitation from Wastewater: P, Mg, N and K Recovery for Fertilizer Production. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 15202–15213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acelas, N.Y.; Flórez, E.; López, D. Phosphorus Recovery through Struvite Precipitation from Wastewater: Effect of the Competitive Ions. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 54, 2468–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Updated Water Quality Guidelines (WQG) and General Effluent Standars (GES) for Selected Parameters; Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 2021. https://emb.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/DAO-2021-19-UPDATED-WQG-AND-GES-FOR-SELECTED-PARAM.pdf. /.

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Water Quality Guidelines and General Effluent Standards; Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 2016. https://emb.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/DAO-2016-08_WATER-QUALITY-GUIDELINES-AND-GENERAL-EFFLUENT-STANDARDS.pdf. /.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. A Plain English Guide to the EPA Part 503 Biosolids Rule; 1994. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-12/documents/plain-english-guide-part503-biosolids-rule.pdf.

- Javaria, S.; Khan, M.Q.; Bakhsh, I. Effect of Potassium on Chemical and Sensory Attributes of Tomato Fruit. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2012, 22, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Niu, X.; Niu, J. Effect of Phosphorus Fertilizer on Growth, Phosphorus Uptake, Seed Yield, Yield Components, and Phosphorus Use Efficiency of Oilseed Flax. Agron. J. 2016, 108, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloyede, F.M.; Agbaje, G.O.; Obisesan, I.O. Effect of NPK Fertilizer on Fruit Development of Pumpkin (Cucurbita Pepo Linn.). Am. J. Exp. Agric. 2013, 3, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzberger, A.J.; Cusick, R.D.; Margenot, A.J. A Review and Meta-Analysis of the Agricultural Potential of Struvite as a Phosphorus Fertilizer. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedelhauser, M.; Mehr, J.; Binder, C.R. Transition of the Swiss Phosphorus System towards a Circular Economy-Part 2: Socio-Technical Scenarios. Sustain. 2018, 10, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Eiroa, B.; Fernández, E.; Méndez-Martínez, G.; Soto-Oñate, D. Operational Principles of Circular Economy for Sustainable Development: Linking Theory and Practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).