1. Introduction

Biomass residues are generated annually in huge amounts as a result of different human activities. The plants’ structure contains three main components which are in different proportions – cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Generally, the cellulose content is predominant, followed by lignin [

1]. Actually, lignin is the main by-product obtained in a plentiful amount from numerous industrial processes [

2], such as food and paper industry, lignocellulose-based biorefinery, etc. [

3,

4,

5]. For example, only the pulping industry generates around 40 million tons of lignin annually [

2]. Because of its calorific value, lignin is often used as solid biofuel in industrial boilers. However, lignin has the potential as feedstock that substitutes the petroleum-based products utilized to manufacture industrial coatings, gels, emulsifiers, etc. [

5,

6]. In fact, lignocellulose biomass is considered a major source of value-added products and bioenergy carrier worldwide [

7].

Last decades the utilization of lignocellulosic matter as source for renewable fuel, chemicals or porous biochar derivatives is gaining considerable attention due to its neutral carbon cycle [

8]. Comprehensive utilization of lignocellulosic biomass is possible after solving the issue related to its decomposition. The bio-refinery might be more effective if along with ethanol production from cellulose and hemicellulose, the factory succeeds to obtain value-added products also from the rested hemicellulose and lignin [

5]. On the other hand, lignin has been widely studied and typically processed for producing bio-based fuels and chemicals [

9].

The significant interest in ethanol production from vegetal raw materials places the question of adequate utilization of the resulted biomass residue. The large internal surface of the lignocellulosic material and the availability of different functional groups could suggest the possible usage of such materials as adsorbents of metal ions, e.g. for water purification purposes. Renewable agricultural residues are produced in bulk as waste, and their storage and management create an environmental problem. The application of agricultural wastes as biosorbents is possible directly or after activation [

10,

11,

12]. Previous investigations [

13] proved that some of the biosorbents` advantages are biodegradability and good adsorption properties due to their morphology and surface functional groups distribution.

Currently, a great research effort is imposed to establish barely studied and effective materials for the disposal of harmful/pathogenic elements or organisms in the air and water environment. In this respect, activated carbon has emerged as promising material. Activated carbon has been used for such purposes as a stand-alone material or as a carrier of active ingredients. However, the requirements and regulations for its production are continuously increasing, especially in terms of its porous texture. It is necessary to create the structure with pores of a specific size, which would increase the material`s selectivity in relation to certain components that need to be removed. Various types of feedstock are used to produce activated carbon. When waste matter is utilized, it reduces the feedstock’s cost and solves the related environmental problems. In view of this, technically hydrolyzed lignin (THL) is of particular interest because is typically generated in large quantities as waste product of certain industrial processes.

The present work aimed at investigating a utilization path for industrial bio-mass residue, namely technically hydrolyzed lignin (THL). In the area of Razlog, Bulgaria, a 140-acre landfill of hydrolysis lignin residue is located. The THL had been deposed outdoor for many years and its total amount is evaluated to be about 350 000 - 400 000 tones. This THL was formed as by-product of a high-temperature diluted sulphuric acid hydrolysis of softwood and hardwood chips to sugars which were further subjected to yeast fodder production. The accumulated huge amount of THL releases different gaseous air pollutants including greenhouse emissions. During the summer period, when the outdoor temperature significantly increases, this matter is also self-igniting. The presently proposed utilization method involved THL carbonization in a Horizontal Tube Furnace (HTF) at a temperature range between 500 and 700 ℃. The obtained biochar was chemically characterized through a set of chemical and physical analyses. The possible biochar applications were discussed in line with the present European effort for circular economy and climate change preservation (e.g. Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive (EU) 2018/2001).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feedstock origin

The investigated THL was a typical example of industrial biomass residue, derived during high-temperature diluted sulphuric acid hydrolysis of softwood and hardwood chips to sugars. In order to develop an efficient biomass processing technology, it is crucial to understand its characteristics and decomposition behavior. Herein, the THL was carbonized at well-controlled conditions.

2.2. Experimental equipment

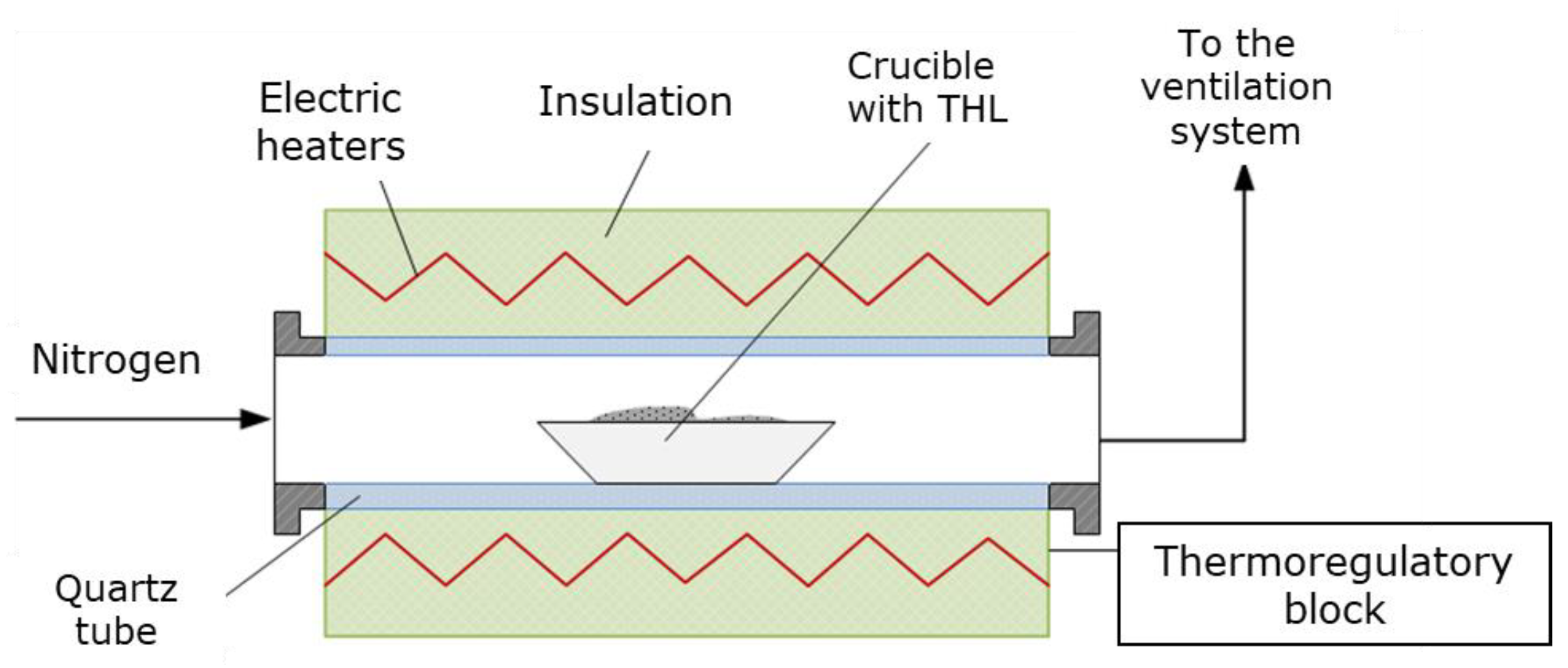

The THL was carbonized in HTF (

Figure 1) at atmospheric pressure and at three different temperatures, 500, 600 and 700 ºС. The residence time of a single sample within the reaction zone was one hour [

14]. The carbonization process was carried out in inert atmosphere (nitrogen), with nitrogen flow rate of 1 l/min, and heating rate of 24 ºС/min. The HTF was thoroughly described elsewhere [

15].

At the end of the process the crucibles, containing biochar, were covered and tempered in a desiccator for at least an hour. Then the samples were weighed with analytical balance. Thus, the biochar mass yield was obtained according to the following equation:

2.3. Feedstock and biochar characterization

The feedstock (THL) and the obtained biochar were chemically characterized through proximate, ultimate, ash, lignocellulosic and calorimetric analyses. The lignocellulosic composition of the THL was determined according to the following methods: cellulose [

16] and lignin [

17].

The ultimate analysis (C, N, S and H) of all types of samples was performed with an Elemental Analyzer Eurovector EA 3000.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) was applied for the ash analysis of both THL and its carbonized products. The analysis was performed by pre-acid decomposition and the elemental content was evaluated by Prodigy High Dispersion ICP-OES, Telledyne Leeman Labs, using US and BDS EN ISO 11885:2009 Standard [

18].

In the present work, simultaneous thermal analyses were carried out with STA PT 1600 TG-DTA/DSC analyzer (LINSEIS Messgeräte GmbH, Germany) in dynamic heating mode from room T (RT=20 °C) to 1000 ºC, with constant heating (10°C/min) and air flow rates (100 ml/min), and in static oxidizing conditions (still air).

The biochar was examined through Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, as well as thermal and nitrogen physisorption analysis. The FTIR spectroscopy was carried out using Varian 660 IR spectrometer. The infrared spectra were collected in the mid-infrared region (4000-400 cm

-1). The samples were prepared by the standard KBr pellets method. The specific surface area of the biochar was determined by low-temperature (77.4 K) nitrogen adsorption in a Quantachrome Instruments NOVA 1200e (USA) apparatus. Before the analyses, the samples were outgassed (argon) at 120 ºC for 16 h in a vacuum. The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were used to evaluate the following parameters: the specific surface area (SBET) was determined through the Brunauer, Emmett and Teller (BET) equation [

13]; the total pore volume (Vt) was estimated in accordance with the Gurvich rule at a relative pressure close to 0.99; the volume of the micropores (VMI) and the specific surface area connected to micropores (SMI), as well as the external specific surface area (SEXT) were evaluated according to V–t-method; additionally, the pore size distributions (PSD) were calculated by equilibrium nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) method using slit shape kernel for carbons.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of carbonization temperature on biochar yield and its chemical composition

Several analytical methods were used (proximate, ultimate, ash, calorimetric and lignocellulosic analyses) to characterize both THL and biochar. The obtained results were summarized in

Table 1. Increasing the carbonization temperature led to significantly reduced content of volatile organic compounds (from 40 to 96 wt. %), increased fixed carbon (from 2.11 to 3.68 times the FC wt. % in THL) and ash content. In addition, H- and O-content was considerably reduced along with the N- and S-content, which for some samples was measured below the detection limit. However, the higher heating value (HHV) and the biochar yield slightly decreased with increasing the carbonization temperature, due to the structural transformations in the carbonization process, relevant to the chosen experimental conditions. The effect was observed also in [

19], concerning biochar samples, obtained at temperatures above 500 ºC. The results were in line with the investigations of [

20]. The authors proved that increasing the carbonization temperature and/or residence time often leads to lower biochar mass yield and HHV.

The lignocellulosic analysis confirmed that during the diluted sulphuric acid hydrolysis of the initial biomass, the hemicellulose was hydrolyzed and the THL became rich in lignin and the cellulose that is resistant to hydrolysis.

The ICP-OES spectroscopy allowed determining the ash composition of THL and its carbonized products.

Table 2 summarizes the mean values from three independent repetitions of each experiment. Except for Pb, Si and Na, the rest of the elements were concentrated in the biochar, showing significant temperature dependence. According to [

19], increasing the carbonization temperature might lead to the volatilization of some metals. Expectedly, increasing the carbonization temperature led to a higher concentration of most of the measured elements in the biochar, generated at 700 ºC.

3.2. Thermal analysis

Thermal stability analyses, such as Thermogravimetric (TG), Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) are typically used to estimate the processes of thermal degradation of biomass and its derivatives.

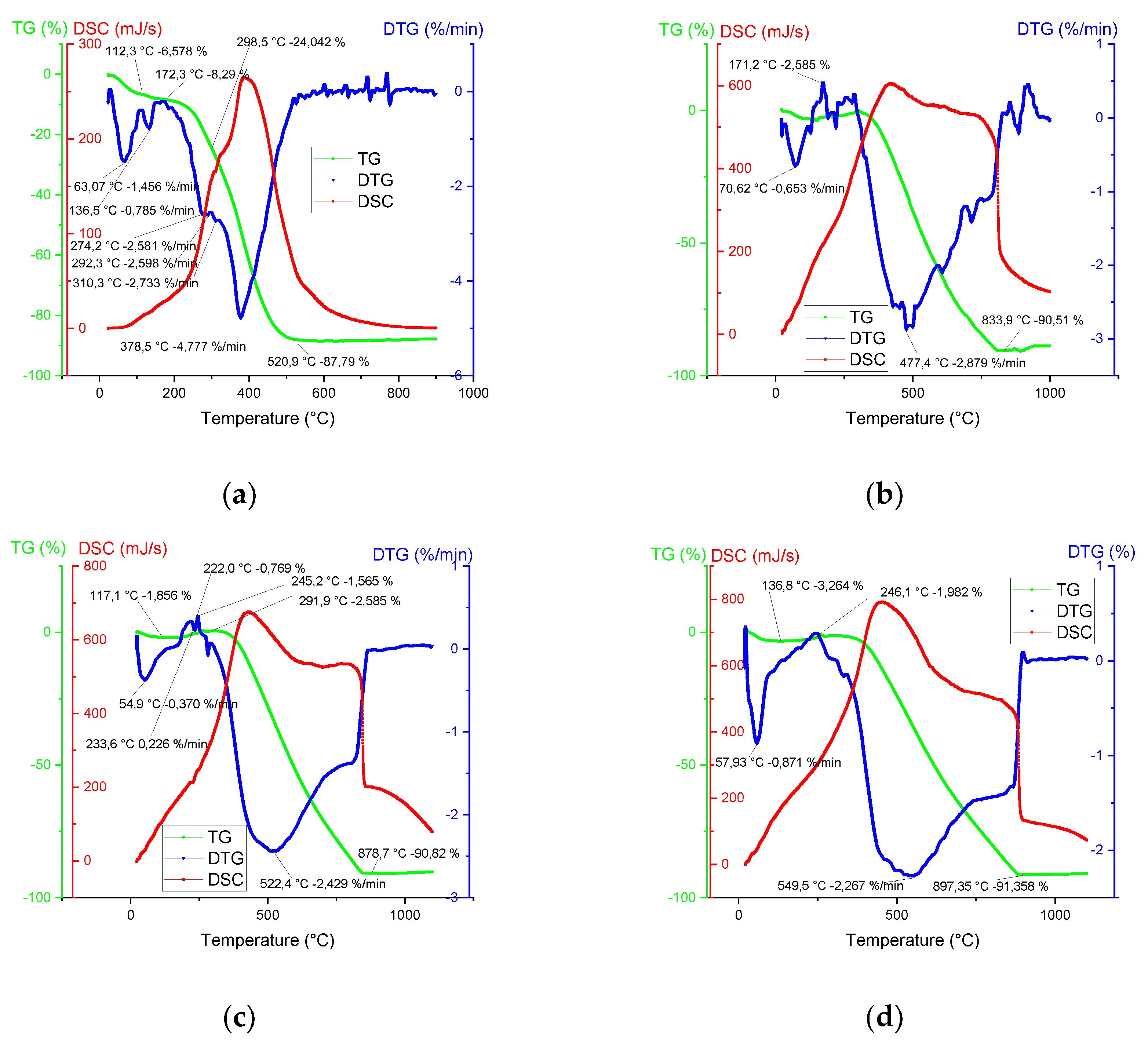

Herein, simultaneous TG-DTA/DSC study was carried out and the thermal conversion of THL and biochar (derived at 500, 600 and 700 ºC) was investigated along with the effects of weight loss and thermal stability. The graphic interpretation of the TG-DTG-DSC temperature dependence is illustrated in

Figure 2. The following three global stages were identified:

Stage 1 - Water vaporization was determined in the temperature range between room temperature (RT) and 246 ºC. Typical for this stage, an endothermic peak was observed, which normally corresponds to the elimination of humidity, followed by broad exothermal peaks.

Stage 2 - Devolatilization and dehydrogenation (of some hydroxides in the mineral composition) took place in the following temperature range: 175 ÷ 900 ºC.

Stage 3 - Fixed carbon combustion was observed at temperatures between 520 and 1000 ºC. The TGA curves of biochar showed that this stage overlapped with stage 2.

The lignin decomposes slower and over a broader temperature range [

22] in comparison to cellulose and hemicellulose [

23]. The effect is attributed to the specific thermal stability of some oxygen-containing functional groups with scission occurring at lower temperature.

As expected, the present thermal analyses showed the occurrence of mostly exothermic reactions. The DSC peaks coincided well with the appearance of the maximum mass loss rates (

Table 3). The peaks at higher temperatures were associated with the thermal decomposition of both lignin and difficult to hydrolyze polysaccharides [

23].

The complex decomposition of THL (see e.g. its DTG curve in

Figure 2 and

Table 3) resulted in at least 5 overlapped steps with maximum mass loss rate at 378.5 °C and a long tail beyond 500 ºC. Instead of one simple peak at 300 ºC, the THL showed a complex destruction process between 270 and 310 ºC, which was related to cellulose degradation [

24].

The maximum mass loss rate of THL (4.78 %/min) was observed at 378.5 ºC. This behavior was related to the low cellulose content in the examined material (

Table 1). The THL thermal decomposition finishes at about 530 ºC. The biochar degradation showed that increasing the carbonization temperature broadened the interval to the total decomposition from 835 ºC (biochar, obtained at 500 ºC) to 895 ºC (biochar - at 700 ºC) as well as increased the peak temperature in the same order.

3.3. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

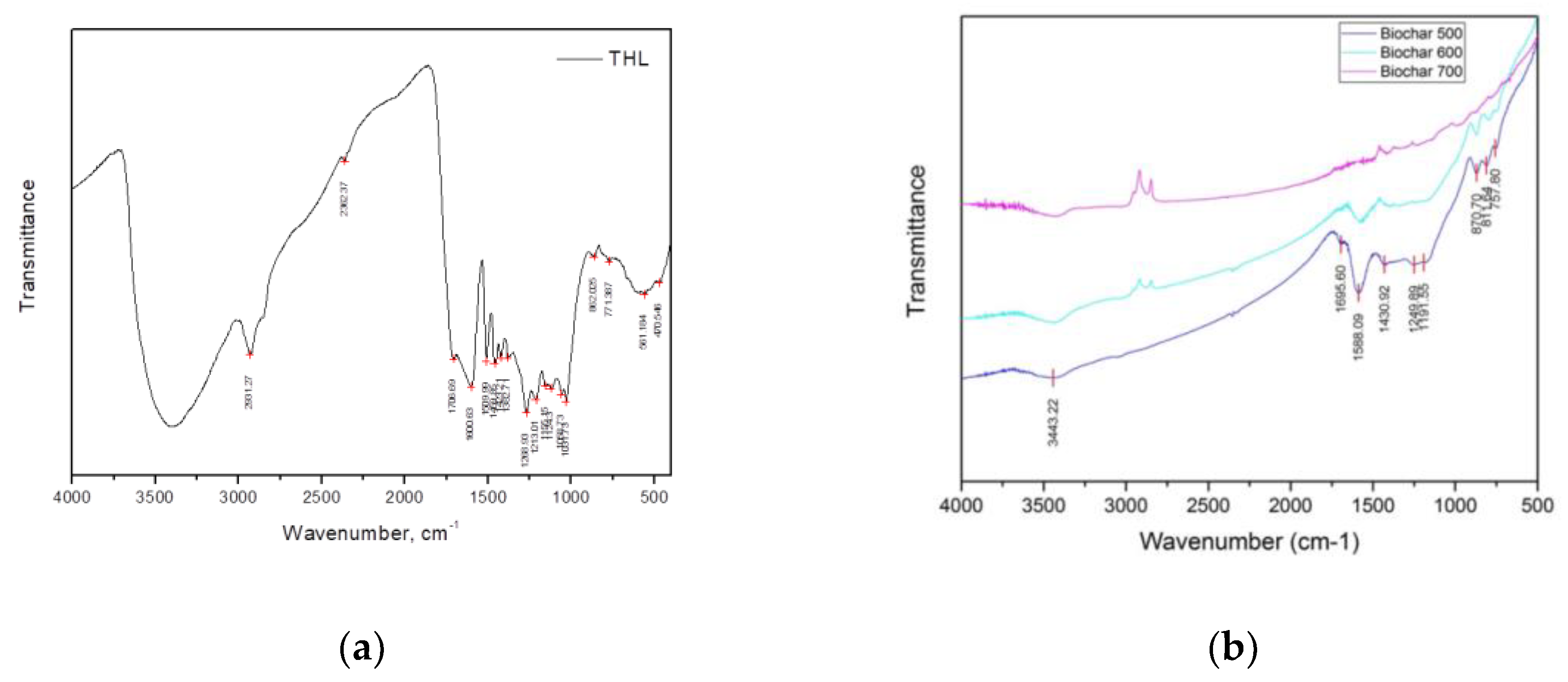

The effect of temperature on the functional groups of THL and its carbonized products was studied also with FTIR spectroscopy (

Figure 3). The FTIR spectrum of THL was influenced by the higher content of lignin and polysaccharides. The wide band at 3400 cm

-1, belonging to the zone 3500-3100 cm

-1, was due to the valence vibrations of alcoholic and hydroxyl groups included in hydrogen bonds. The intensive bands at 2931 and 2800 cm

-1 referred to different types of valence vibrations of C H bonds in the methyl and methylene groups. The band at 1710 cm

-1, falling in the range 1600-1760 cm

-1, was characteristic of the vibrational oscillation of the group C = O in alkyl-aromatic ketones. In particular, a ketocar-bonyl group is typically supported by β-carbon atom of a propane chain [

25]. The bands at 1600 and 1509 cm

-1 were associated with vibrations of aromatic nuclei. The bands at 1459 cm

-1 and 1382 cm

-1 were associated with the deformation vibrations of CH in the methyl and methylene groups. The band at 1155 cm

-1 refers to C-O-C asymmetric vibrational oscillation in ether groups. The 862 cm

-1 band was attributed to deformation vibrations of the CH bonds in a three-substituted aromatic nucleus. The next band at 771 cm

-1 was due to deformation vibrations of the CH bonds in a mono-substituted aromatic nucleus.

The FTIR spectra of biochar proved that their functional groups were gradually lost with increasing the carbonization temperature, where the role of the polycyclic aromatic structures was significant [

19]. The band at 3443 cm

-1 referred to O–H stretching of H-bonded hydroxyl groups, while the one at 2870 cm

-1 was ascribed to symmetric C–H stretching of aliphatic hydrocarbon (e.g. from the propane chain of the monomer units in lignin). The band at 1695 cm

-1 referred to C=O stretching vibrations of alkyl-aromatic ketones, whereas the bands at 1600 cm

-1 and 1430 cm

-1 were connected with C=C stretching vibrations of aromatic components.

The bands at 870 cm-1, 811 cm-1, and 757 cm-1 were due to C-H bending vibrations from three-substituted, di-substituted, and mono-substituted aromatic nuclei, respectively. The band at 1191 cm-1 was attributed to C–O–C symmetric stretching vibrations in ester groups, while the bands, detected between 870 cm-1 and 675 cm-1 were associated with C-H bending vibrations.

3.4. Surface Area and Pore Volume

The evaluation of the specific surface area of the THL and biochar was carried out by adsorption of nitrogen at -196℃. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms were used to calculate the specific surface area using the BET equation [

13]. The results are summarized in

Table 4.

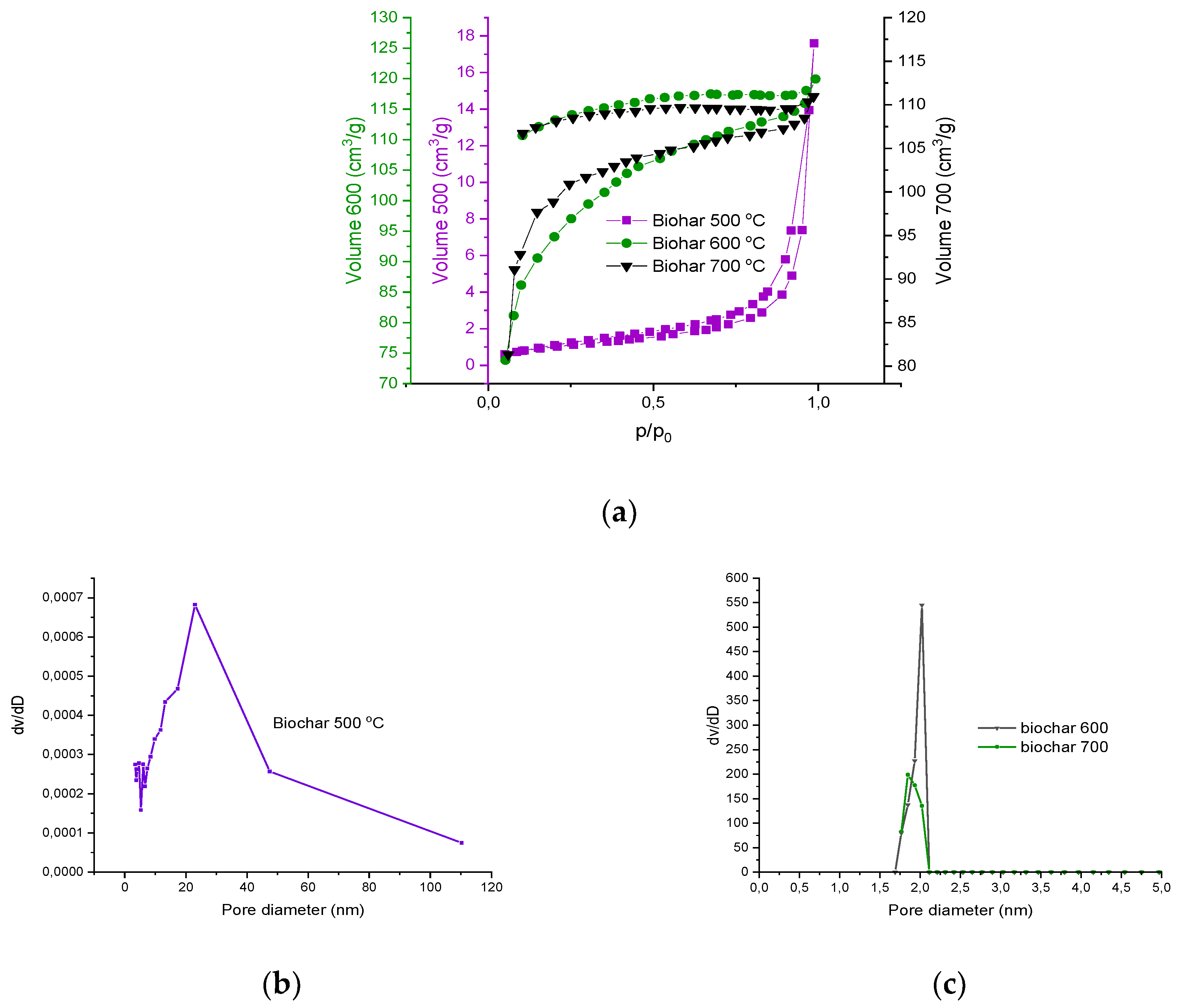

The isotherm of THL is of type II, according to IUPAC classification, evidencing the material is nonporous or microporous (

Figure 4). The hysteresis loop is of type H3, which could be attributed to aggregates of plate-like particles giving rise to slit-shaped pores.

The isotherms of the samples of biochar are of type I, indicating that the micropores were dominating the textural properties. The hysteresis loop of H4 type herein started at relatively higher pressure, due to which two types of pores were considered: mesoporous and microporous. The H4 loop is often attributed to narrow slit-like pores. The hysteresis loops do not close for the biochar samples. This could be due to hindered evaporation of the trapped nitrogen because of the heterogeneous coal surface or ink-bottled pores [26, 27].

These results were confirmed by the specific surface area estimations. The BET equation, used for determining the surface area, was applied in the interval of relative pressure (Р/Рo) between 0.05 and 0.35, considering partial surface occupation.

The pore size distribution was also plotted for all examined biochar samples and generally confirmed the results for the porous texture, which were deduced from the adsorption isotherms. The biochar, obtained at 600 and 700 ºC showed a narrow interval of pore-diameter variations (1÷2 nm). Thus, an opportunity is foreseen for selective adsorption of molecules, having particular size and/or chemical structure, typical for some microporous adsorbents.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, technically hydrolyzed lignin was utilized and the effect of carbonization temperature on the biochar mass yield and its properties was investigated. Increasing the carbonization temperature (500 ÷ 700 ºC), led to the following general conclusions:

The biochar mass yield slightly decreased with increasing the carbonization temperature.

The chemical characterization showed biochar with gradually reduced content of volatile matter, between 40 and 96 wt. % in contrast to THL. The fixed carbon content was increased from 2.11 to 3.68 times the wt. % of fixed carbon in the THL, along with slightly increased ash content. As expected, the ultimate analysis showed significant increase in the C-content, but considerably reduced H- and O-composition, whereas the reduction of the N- and S-content in the high-temperature biochar showed values below the detection limit. This suggested possible biochar application as solid biofuel.

The textural analysis (FTIR spectroscopy) showed that the functional groups were gradually lost thus, forming materials characterized merely by polycyclic aromatic structures and high condensation rate.

The nitrogen physisorption analysis revealed that the proposed utilization technology of THL (specifically the carbonization at 600 and 700 ºC) produced biochar, having the properties typical for the microporous adsorbents, which allows for selective adsorption of specific molecules. Based on the latest observations, another possible application was assumed - as catalyst.

Author Contributions

I.N.: conceptualization, methodology, experimental work, results analysis and visualization, writing and editing original draft, funding acquisition; T.R.: methodology, results analysis and visualization, writing—original draft preparation, funding acquisition; T.P.: experimental work, writing—review and editing O.S.: biomass carbonization, biochar characterization, results analysis and visualization, I.V.: biochar chemical characterization, results analysis and visualization.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Education and Science (MES) of Bulgaria and the Bulgarian National Science Fund.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from the National Science Program "Environmental Protection and Reduction of Risks of Adverse Events and Natural Disasters", approved by the Resolution of the Council of Ministers № 577/17.08.2018, supported by the Ministry of Education and Science (MES) of Bulgaria (Agreements № Д01-363/17.12.2020,№ Д01-279/03.12.2021 and № Д01-271/09.12.2022), as well as from Project “Aerosols and their organic extractives, derived during biomass conversion – cytotoxic and oxidative response of model systems of pulmonary cells (AEROSOLS)” CONTRACT № КП-06-Н44-5/14.07.2021, supported by the Bulgarian National Science Fund (BNSF), MES for ensuring the technical maintenance of the laboratory equipment needed for biomass thermal conversion. The authors would like to thank the Research and Development Sector at the Technical University of Sofia for the financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tao, J. , Li, S., Ye, F., Zhou, Y., Lei, L., Zhao, G. Lignin - An underutilized, renewable and valuable material for food industry. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, 2020; 60, 2011-2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, E. , Alrawashdeh, K.A.B., Masek, O., Skreiberg, Ø., Corona, A., Zampilli, M., Wang, L., Samaras, P., Yang, Q., Zhou, H., Bartocci, P., Fantozzi, F. Production and use of biochar from lignin and lignin-rich residues (such as digestate and olive stones) for wastewater treatment. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2021, 158, 105263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.-M. , Hwang, K.-R., Kim, Y.-M., Jae, J., Kim, K.H., Lee, H.W., Kim, J.-Y., Park, Y.-K. Recent progress in the thermal and catalytic conversion of lignin. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2019, 111, 422–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotana, F. , Cavalaglio, G., Nicolini, A., Gelosia, M., Coccia, V., Petrozzi, A., Brinchi, L. Lignin as co-product of second generation bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass. Energy Procedia, 2014, 45, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, A. , Bajar, S., Kour, H. et al. Lignocellulosic Biomass Valorization for Bioethanol Production: a Circular Bioeconomy Approach. Bioenerg. Res, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Corato, U. , De Bari, I., Viola, E., Pugliese, M.: Assessing the main opportunities of integrated biorefining from agro-bioenergy co/by-products and agroindustrial residues into high-value added products associated to some emerging markets: a review. Renew Sust Energ Rev, 2018, 88, 326–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V. , Kumar, A., Bilal, M., Nguyen, T.A., Iqbal, H.M.N. Chapter 12 - Lignin removal from pulp and paper industry waste streams and its application, Editor(s): Bhat, R., Kumar, A., Nguyen, T.A., Sharma, S., In Micro and Nano Technologies. Nanotechnology in Paper and Wood Engineering, Elsevier, 2022, pp. 265-283, ISBN 9780323858359. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. , Anushree, Kumar, J., Bhaskar, T. Utilization of lignin: A sustainable and eco-friendly approach. Journal of the Energy Institute, 2020, Vol. 93, Issue 1, pp. 235-271, ISSN 1743-9671. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. , Chen, S.S., Zhang, S., Ok, Y.S., Matsagar, B.M., Wu, K.C.-W., Tsang, D.C.W. Advances in lignin valorization towards bio-based chemicals and fuels: Lignin biorefinery. Bioresource Technology, 2019, 291, 121878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumathi, K.M.S. , Mahimairaja, S. , Naidu, R. Use of low-cost biological wastes and vermiculite for removal of chromium from tannery effluent. Bioresour Technol, 2005, 96, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dias, J. , Alvim-Ferraz, M., Almeida, M., Rivera-Utrilla, J., Sanchez-Polo, M. Waste materials for activated carbon preparation and its use in aqueous-phase treatment: a review. J Env Manage, 2007, 85, 833–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannidou, O. , Zabaniotou, A. Agricultural residues as precursors for activated carbon production - a review. Renew Sustain Energ Rev, 2007, 11, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassileva, P. S. , Radoykova, T. Hr., Detcheva, A. K., Avramova, I. A., Aleksieva, K. I., Nenkova, S. K., Valchev, I. V., Mehandjiev, D. R. Adsorption of Ag+ ions on hydrolyzed lignocellulosic materials based on willow, paulownia, wheat straw and maize stalks. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2016, 13, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.F. , Ribau, J.P., Costa, M. A decision support method for biochars characterization from carbonization of grape pomace. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2021, 145, 105946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandov, O. Construction of a flow reactor for the combustion/pyrolysis of biomass fuels. Proceedings of XXIV Scientific conference with international participation FPEPM 2019, Sozopol, Bulgaria, 17 – , pp. 258-268, ISSN 1314 – 5371. 20 September.

- Kürschner, K. , Hoffer, A. Cellulose and cellulose derivatives. Fresenius’ J Anal Chem, 1933, 92:145–54.

- Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry. TAPPI T 222 om-11: Acid-insoluble lignin in wood and pulp, 2011.

- ISO 11885:2007. Water quality - Determination of selected elements by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), 2007. Available online: https://bds-bg.org/bg/project/show/bds:proj:80192.

- Zhao, S.-X. , Ta, N., Wang, X.-D. Effect of Temperature on the Structural and Physicochemical Properties of Biochar with Apple Tree Branches as Feedstock Material. Energies, 2017, 10, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaka, S. , Sharara, M. A., Ashworth, A., Keyser, P., Allen, F., Wright. A. Characterization of Biochar from Switchgrass Carbonization. Energies, 2014, 7, 548–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valchev, I. , Yordanov, Y., Savov, V., Antov, P. Optimization of the Hot-Pressing Regime in the Production of Eco-Friendly Fibreboards Bonded with Hydrolysis Lignin. Periodica Polytechnica Chemical Engineering, 2022, 66, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, A. , Pizarro, C., García, R., Bueno, J.L., Lavín, A.G. Determination of kinetic parameters for biomass combustion. Bioresource Technology, 2016, 216, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brebu, M. , Vasile C. Thermal degradation of lignin- a review. Cellulose Chem. Technol., 2010, 44, 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnon, B. , Py, X., Guillot, A., Stoeckli, F., Chambat, G. Contributions of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin to the mass and the porous properties of chars and steam activated carbons from various lignocellulosic precursors. Bioresource Technology, 2009, 100, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draganova, R. , Nenkova S. Chemistry and structure of plant tissues, Publisher: University of Chemical Technology and Metallurgy, Sofia, 372, in Bulgarian, 2002, ISBN 954-8954-16-8.

- Tang, X. , Wang Z., Ripepi N., Kang B., Yue G. Adsorption affinity of different types of coal: mean isosteric heat of adsorption. Energy Fuels, 2015, 29, 3609–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L. , Tang, X., Wang, Z., Peng, X. Pore characterization of different types of coal from coal and gas outburst disaster sites using low temperature nitrogen adsorption approach. International Journal of Mining Science and Technology, 2017, 27, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).