1. Introduction

The concrete industry has many opportunities regarding the development of products that achieve the goals of zero-energy consumption in buildings, drastically reducing the carbon footprint and ensuring the environmental protection requirements, as well as implementing the principles of the circular economy. Concrete with high thermal resistance as a cement-based material can significantly contribute to improving the energy efficiency performance of a building. As mentioned in the first part of the study [

1], in which crumb rubber concrete was analyzed as a cement-based material, in order to reduce the thermal conductivity of concrete and improve its insulation properties, it is necessary to examine the options for increasing the thermal performance of concrete by using other types of waste from materials with heat-insulating properties, in building envelope elements, with minimal impact on the environment. Concrete is a material widely used in the construction industry, the raw materials in its compositions being natural aggregates, cement, water and admixtures. Aggregates represent approximately 60-75% of the concrete mixture by volume and cement and water make up the rest. Therefore, in the research studies carried out in the laboratory, various secondary raw materials (wastes) were explored, as alternatives, in order to minimize the impact of concrete on the environment and reduce environmental pollution, following the trend of global initiatives [

2], by prioritizing the use of materials with higher thermal performance in construction and renovation of buildings [

3], as well as through waste recycling.

Perlite, a naturally occurring alumino-siliceous amorphous volcanic material derived from crude perlite rock, is commonly used in construction and is found in various countries, including Italy, Hungary, Turkey, Greece, Japan, and the United States [

4,

5,

6]. The global production of perlite is increasing, driven by rising demand. As such, material producers in the perlite industry need to improve the collection of perlite waste and in creating an economically viable system encouraging its use.

The substitution of natural aggregate with expanded perlite in mixtures has been shown to reduce their thermal conductivity due to the porous structure of the perlite [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. The thermal conductivity of perlite significantly impacts the reduction of thermal conductivity in perlite concretes [

16], with an increase in the content of expanded perlite leading to a greater reduction. Oktay et al. [

23] found that the use of 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% volume of 0.15-11 mm perlite particles as a natural sand substitution resulted in 22.96 %, 38.01 %, 64.23 %, 74.36 %, and 81.48 % reductions in the 28-day thermal conductivity of concretes, respectively.

The research on perlite concrete has shown that replacing natural sand with expanded perlite can significantly reduce the density of the mixture, with some studies reporting reductions of up to 65.46 % [

11]. According to the research conducted by Türkmen and Kantarcı [

25,

26], partially replacing natural sand with perlite (0-4 mm size) at volumes of up to 15% reduces the unit weight of the concrete mixture that is less than 1.36 %. At higher levels of perlite substitution (over 50 %), the density of the mixture can decrease by as much as 500 kg/m

3 due to the low specific gravity of perlite, which reduces the unit weight of the mixture [

10]. While the low density of perlite concrete can be advantageous, it can also lead to lower mechanical properties [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Compressive strength is an essential characteristic of concrete as a construction material. Studies have found that partially replacing natural sand with perlite can lead to a significant reduction in the 28-day compressive strength of the resulting concrete mixture [

22,

24]. For instance, one study found that substituting natural aggregate with perlite (0.15-11mm size) at levels of 10 %, 20 %, 30 %, 40 %, and 50 % resulted in a reduction in compressive strength of 39.8 %, 63.33 %, 80.69 %, 84.29 %, and 90.58 %, respectively [

23]. The incorporation of expanded perlite as an aggregate in concrete mixtures can increase porosity, which can lower the density and strength of the mixture [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

In the light of the information mentioned above, this paper aims to investigate the behavior of perlite concrete, highlighting the impact of the use of perlite on the properties, in order to identify some construction products, with characteristics that innovatively combine only the positive results obtained in the laboratory research carried out. Even though there are many different studies on perlite concrete, there is a lack of specific application areas for this material.

The research aims to find solutions for the use of this cement-based material, in which perlite has replaced sand, to make masonry blocks, as building envelope elements. To analyze perlite concrete in detail, an experimental program was implemented to study its general behavior, including density, compressive strength, thermal conductivity and microscopic characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, the perlite granules (

Figure 1) utilized in the concrete mixture had a size of 0-4 mm size and were not subjected to any form of treatment. In the used form, the perlite granules can be manufactured products, or from waste on the construction site that can be reused. They have the same material properties, as well as the size of the granules from 0 to 4 mm.

As mentioned in the first part of the study regarding the assessments of thermal and mechanical properties of cement-based materials in which the crumb rubber concrete was analyzed [

1], the laboratory tests for the perlite concrete use the same control concrete mixture composition [

1], with an A/C ratio of 0.55. The concrete strength class is C 20/25, the exposure class is XC3 XA1, and the consistency class is S3. The constituents of control concrete mixture are shown in

Table 1.

Based on the review of previous research and the fact that the perlite granules range in size from 0-4 mm, samples were prepared with three distinct mixture compositions in which 10 %, 20 %, and 30 % of the 0-4 mm aggregate were replaced. The percentage of replacement of the aggregates with perlite granules was determined by equivalent volume.

Table 1 displays the amounts of constituent materials used in the control concrete and in perlite concrete.

To evaluate the concrete mixtures' compressive strength and thermal conductivity properties, cubic samples were prepared for each composition. These samples had a height and width of 150 mm and were tested 28 days after being poured into the molds, according to the standardized methodology. After 28 days, the samples underwent thermal conductivity testing using a portable device, the ISOMET 2114. This device has a surface sensor designed for hard materials and uses a dynamic investigation method to quickly measure the thermo-mechanical characteristics of the samples [

1]. The dynamic method involves applying temperature changes to the sample and measuring the resulting heat flow. The temperatures of the sample are recorded periodically over time, and allows the calculating the thermal conductivity based on the temperature changes and the heat flow through the sample.

The compressive strength of a material is a measure of its resistance to deformation under a compressive load. In this study, the samples were tested for their compressive strength using a testing machine, the ZwickRoell SP1000 hydraulic equipment [

1]. The tests were conducted according to standard EN 12390-3:2009 requirements and protocols. The compressive force was applied to the samples perpendicular to the pouring direction, with a loading speed of 0.2 MPa/s and an accuracy of less than 1% [

1].

3. Results

3.1. Density

After completely hardening the samples, their weight and volume were measured to calculate their density (ρ = m/V). The results were calculated for the four mixture compositions and are presented in

Table 2. Analyzing the results, the perlite concrete samples have a lesser density than the control samples, with a reduction of 4.45 % in the case of 10 % perlite, of 5.89 % in the case of 20 % perlite, and of 7.83 % in the case of 30 % perlite.

3.2. Thermal Conductivity

To understand the influence of the perlite in the concrete mixture, it is mandatory to analyze it from the standpoint of thermal conductivity. Concluding reports were provided with completed characteristic thermomechanical measurements, including thermal conductivity coefficient, [W/mK]. Measurements were taken on all sides of each cubic sample, to ensure accuracy and validate the results. The samples were subjected to thermal conductivity testing, using the ISOMET 2114, (

Figure 2).

As previously reported in the study on crumb rubber concrete [

1], the thermal conductivity measurements for control samples vary from 2.05 W/mK to 2.26 W/mK for a heat flow parallel to casting, and from 2.48 W/mK to 2.58 W/mK for a heat flow perpendicular to casting direction [

1]. The findings indicate that the thermal conductivity parallel to casting is 13-20 % higher than the average of the thermal conductivity values measured perpendicular to the casting [

1], (

Table 3).

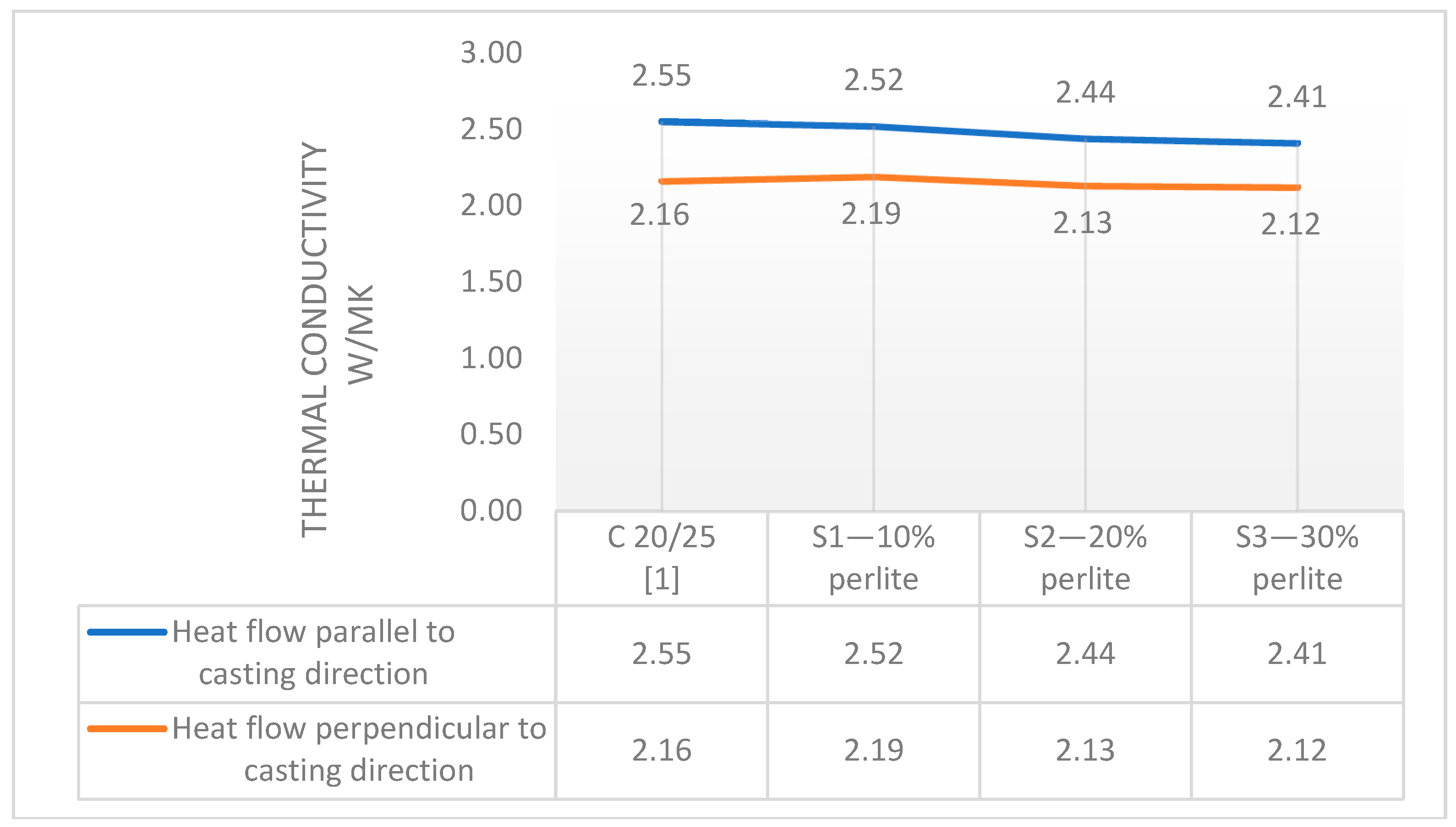

The samples of perlite concrete mixture with 10 % of the sand replaced with perlite were subjected to tests for thermal properties. Thermal conductivity measurements presented in

Table 4, vary from 2.14 W/mK to 2.30 W/mK for heat flow perpendicular to the casting and 2.52 W/mK for heat flow parallel to the casting direction. The thermal conductivity for measurements in parallel is 14.6 % higher than the average of the thermal conductivity values measured when heat flow is perpendicular to the casting. The improvement in the thermal conductivity, meaning in fact a decrease, is insignificant compared to the control samples. The rsults show a decrease of less than 1% (from 2.55 W/mK to 2.52 W/mK), (

Figure 3).

The thermal properties of the concrete mixtures were tested after replacing 20 % and 30 % of sand with perlite, and the results are documented in

Table 4. When 20 % of the aggregates were replaced with perlite, the thermal conductivity values ranged from 2.12 W/mK to 2.15 W/mK for heat flow perpendicular to the casting, and 2.44 W/mK for heat flow parallel to the casting direction (

Table 4). A comparison of the readings indicates that the thermal conductivity value is 14.2 % higher than the average of the thermal conductivity values measured for heat flow perpendicular to the casting direction. There was a 4.7% decrease in thermal conductivity for heat flow parallel to the casting direction (from 2.55 W/mK to 2.44 W/mK) and 1.2 % for heat flow perpendicular to the casting (from 2.16 W/mK to 2.13 W/mK) compared with the control samples, (

Figure 3).

The samples with the replacement of 30 % of sand with perlite were also subjected to measurements (

Table 4). Thermal conductivity values vary from 2.07 W/mK to 2.25 W/mK for heat flow perpendicular to the casting, and 2.41 W/mK for heat flow parallel to the casting direction. It is noticed that the thermal conductivity for heat flow parallel to the casting direction is 13.6 % higher than the average of the thermal conductivity values perpendicular to the casting. Compared to the control samples, the concrete mixture with a perlite replacement of 30 % showed an improvement in its thermal conductivity. There was an improvement by decreasing of 6 % in thermal conductivity for heat flow parallel to the casting direction, (from 2.55 W/mK to 2.41 W/mK), and 1.9 % for heat flow perpendicular to the casting direction (from 2.16 W/mK to 2.12 W/mK), (

Figure 3).

The results conclude that the thermal conductivity of the perlite concrete mixture decreases by an average of 3 % as the ratio of perlite increases from 10 % to 30 %.

3.3. Compressive Strength

Compressive strength is the primary parameter used to evaluate concrete's mechanical properties, which measures how much force a material can withstand before it breaks or crushes. The strength class of the material is determined based on the compressive strength value. The samples were subjected to uniaxial compression using a hydraulic testing machine to determine the compressive strength of the four different concrete mixture compositions (

Figure 4). The compressive strength of the samples was then calculated based on the testing results.

The C20/25 samples used in this study and those examined in the crumb rubber concrete study [

1] exhibit an average compressive strength value of 25.98 MPa. In contrast, the perlite concrete samples display values of 24.23 MPa (10 %), 23.80 MPa (20 %), and 22.44 MPa (30 %) (

Table 5). The compressive strength of the concrete mixture decreases as the percentage of perlite increases. For a 10 % ratio, the decrease in compressive strength is relatively small, at 6.75 %. However, as the ratio of perlite increases to 20 % and 30 %, the reduction in compressive strength becomes more significant, with decreases of 8.40 % and 13.66 %, respectively.

The outcomes of the compressive strength tests for the concrete mixture with perlite replacements were consistent with previous research on the topic. The compressive strength of the mixture decreases as the ratio of perlite increases. This reduction in compressive strength was expected, as previous studies have also reported a similar trend.

3.4. The Variation of the Physio-Mechanical Characteristics of the Perlite Concrete upon the Total Replacement of the 0-4 mm Sort with Perlite

Previous studies on the use of perlite in concrete focused on replacing a certain percentage of the fine fraction of the aggregate to determine the effect on the thermal conductivity of the resulting mixture. However, these studies did not observe a significant improvement in thermal conductivity. As a result, the scope of the research was expanded to 100 % replacement of 0-4 mm aggregate with perlite. This allowed for a more thorough investigation into the potential benefits of using perlite in concrete.

Two sets of concrete compositions were prepared, each consisting of cubic samples with a side length of 150 mm. These samples were analyzed for both their thermal conductivity and compressive strength. The first set of samples was a control, using the standard C16/20 class concrete mixture composition without any replacements. The choice of the resistance class was made based on the observations from previous research, which showed that the resistance shows significant decreases when sand is replaced with perlite, but also due to the condition of the minimum resistance that must be ensured for the concrete when removing the formwork.

The second set of samples used perlite to completely replace the 0-4 mm aggregate. The perlite was evenly distributed throughout the concrete mixture during the mixing process using a concrete mixer. Each sample's thermal conductivity was measured on each side of the cube to ensure accurate data, and the average of these measurements was used in the analysis.

In order to measure the compressive strength of the control concrete and the perlite concrete, a compressive force was applied to the samples perpendicular to the pouring. The loading speed for the test was 0.2 MPa/s, using a WAW-600E press. The average compressive strength of the control samples was 20.96 MPa, while the average compressive strength of the samples with perlite was 18.55 MPa. The resuts highlighted a reduction in compressive strength of 11.49 % (as shown in

Table 6).

The density of the concrete mixture with the perlite replacement was determined and the results showed a significant decrease in the density of the new mixture, as listed in

Table 7.

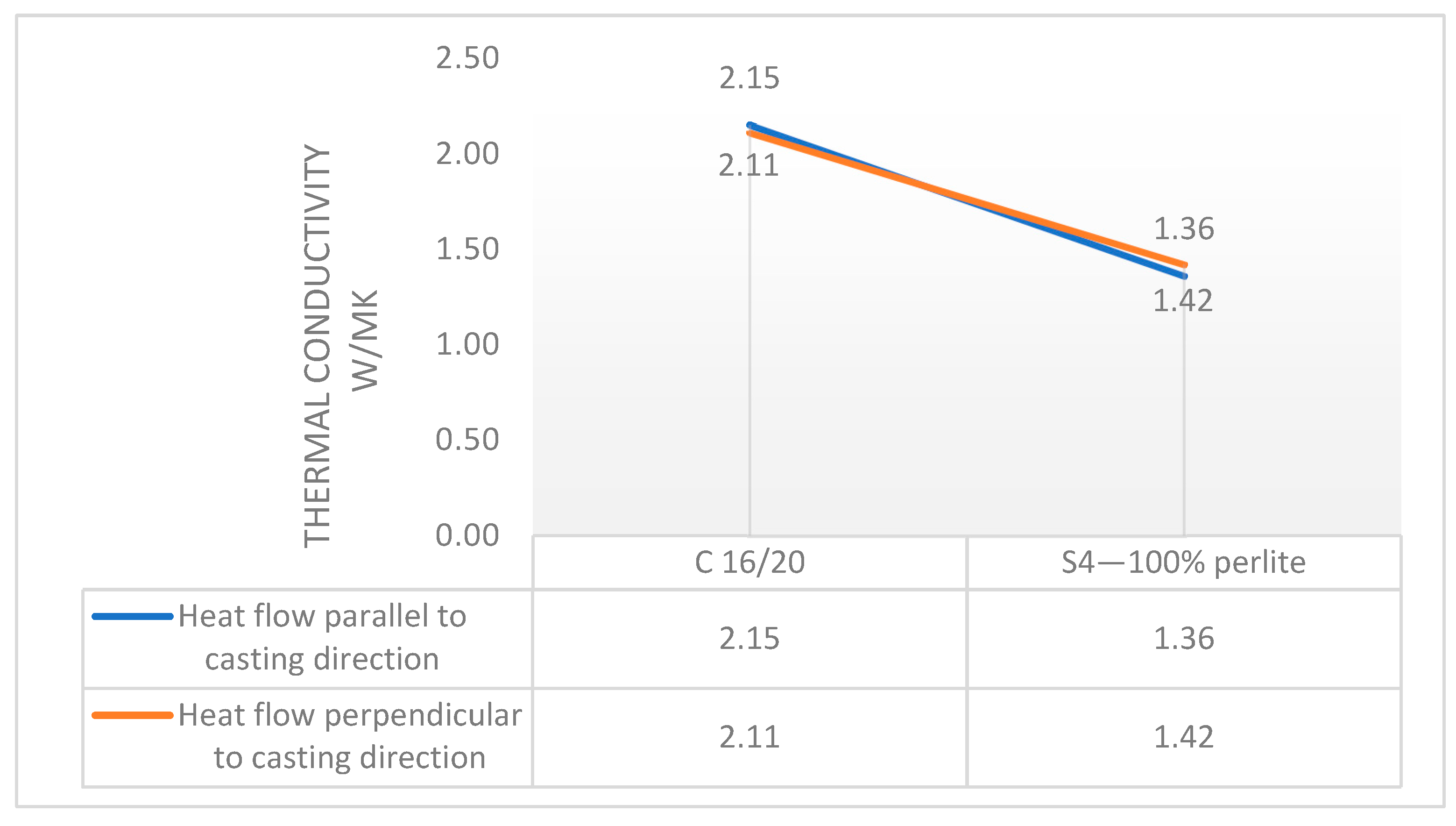

The thermal conductivity of the control samples was measured for heat flows parallel and perpendicular to the casting direction. The values for these measurements ranged from 1.72 W/mK to 2.3 W/mK for heat flow perpendicular to the casting direction and from 2.04 W/mK to 2.27 W/mK for heat flows parallel to the casting direction (

Table 8). These values are similar to those obtained in an earlier set of control samples (as listed in

Table 3). It was observed that the thermal conductivity for heat flows parallel to the casting direction was slightly higher than the average of the thermal conductivity values for heat flows perpendicular to the casting direction, with a difference of 1-4%.

In addition to the measurements on the control samples, the thermal conductivity of the concrete mixture with perlite was also determined. The values for these measurements ranged from 1.12 W/mK to 1.64 W/mK for heat flows perpendicular to the casting direction, and from 1.17 W/mK to 1.5 W/mK for heat flows parallel to the casting direction, (

Table 9).

Compared to the control samples, the concrete mixture with perlite significantly improved thermal conductivity. For the heat flow parallel to the casting, there wis an improvement of 36.74 % (from 2.15 W/mK to 1.36 W/mK). For the heat flow perpendicular to the casting surface, there is an improvement of 32.7 % (from 2.11 W/mK to 1.42 W/mK) (

Figure 5).

3.5. The Influence of Perlite Concrete with 100% Sand Replacement on a Thermal Bridge

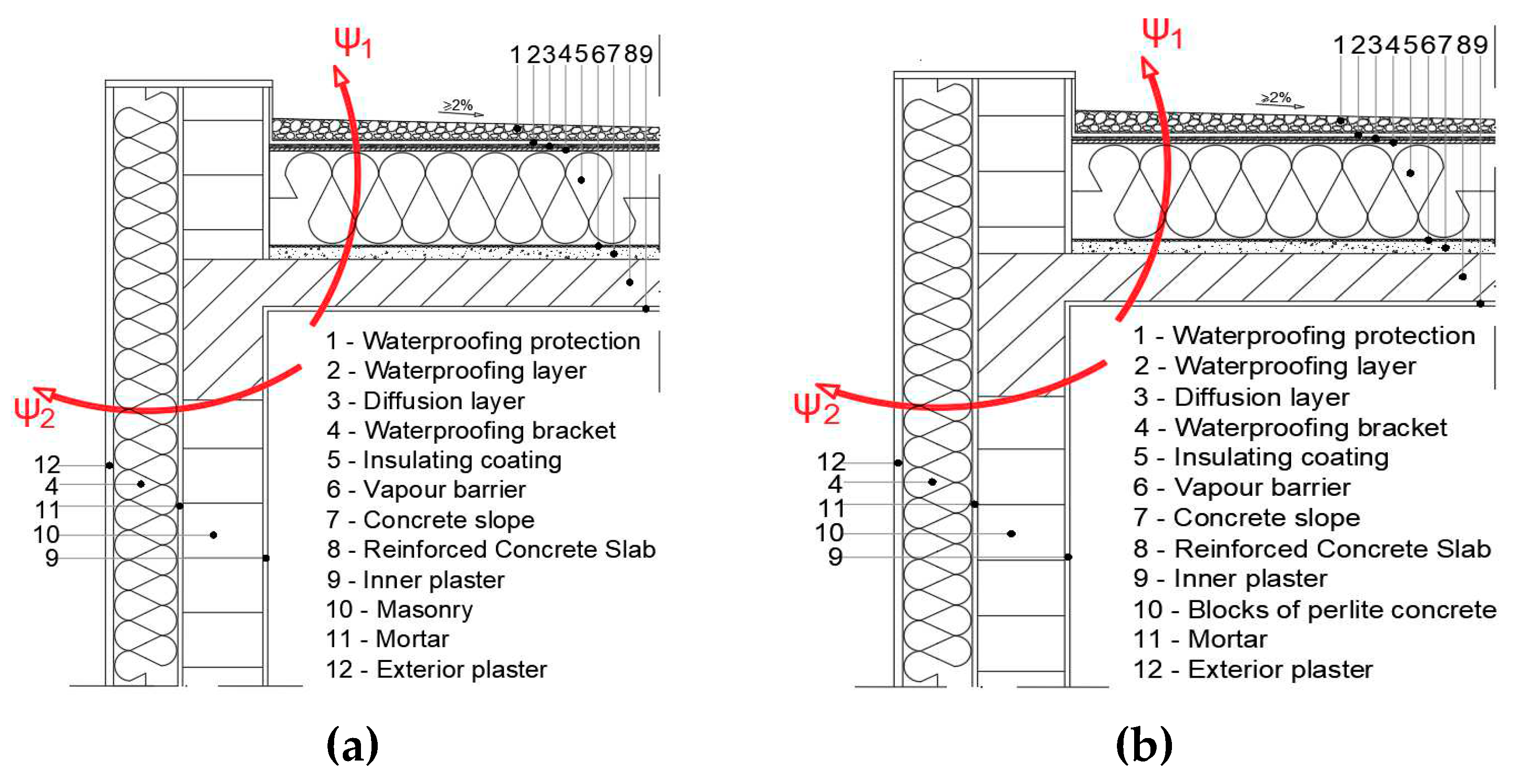

The compression strength of perlite concrete with 100% replaced sand classified the material as class C12/15, which is not suitable for its use in structural elements. A possible use of it can be in the masonry blocks from which the panels can be made for the non-load-bearing walls in the envelope of a building. The thermal resistance of the envelope is an important parameter for the building. The areas in the envelope, which adversely influence both energy consumption and thermal comfort, are the areas with reduced thermal resistance, known as thermal bridges. In this context, a study on the influence of the use of perlite concrete on the indicators that characterize thermal bridges (the studied parameters being the heat flows), can substantiate its use in manufactured blocks for masonry.

The thermal bridge located at the intersection of outer wall with terrace slab (exterior corner area) was selected. A compare analysis for bridge thermal evaluation when clay bricks (case I) and perlite concrete blocks (case II) were used for masonry of the exterior wall panels have been performed,

Figure 6, [

27,

28]. The characteristic data for the main materials used, as input parameters, are presented in

Table 10, and for others materials are presented in

Table 11, [

27,

28]. The analysis was done by using specialized programs for the design and analysis of thermal bridges, as well as for the presentation of the geometric and technical details of the structure. The programs used were: Autocad, which provides graphic models and RDM 6.17, which provides results on the heat flows of each analyzed case, [

29,

30]. The results of linear thermal bridges coefficients are presented in

Table 12 and depicted in

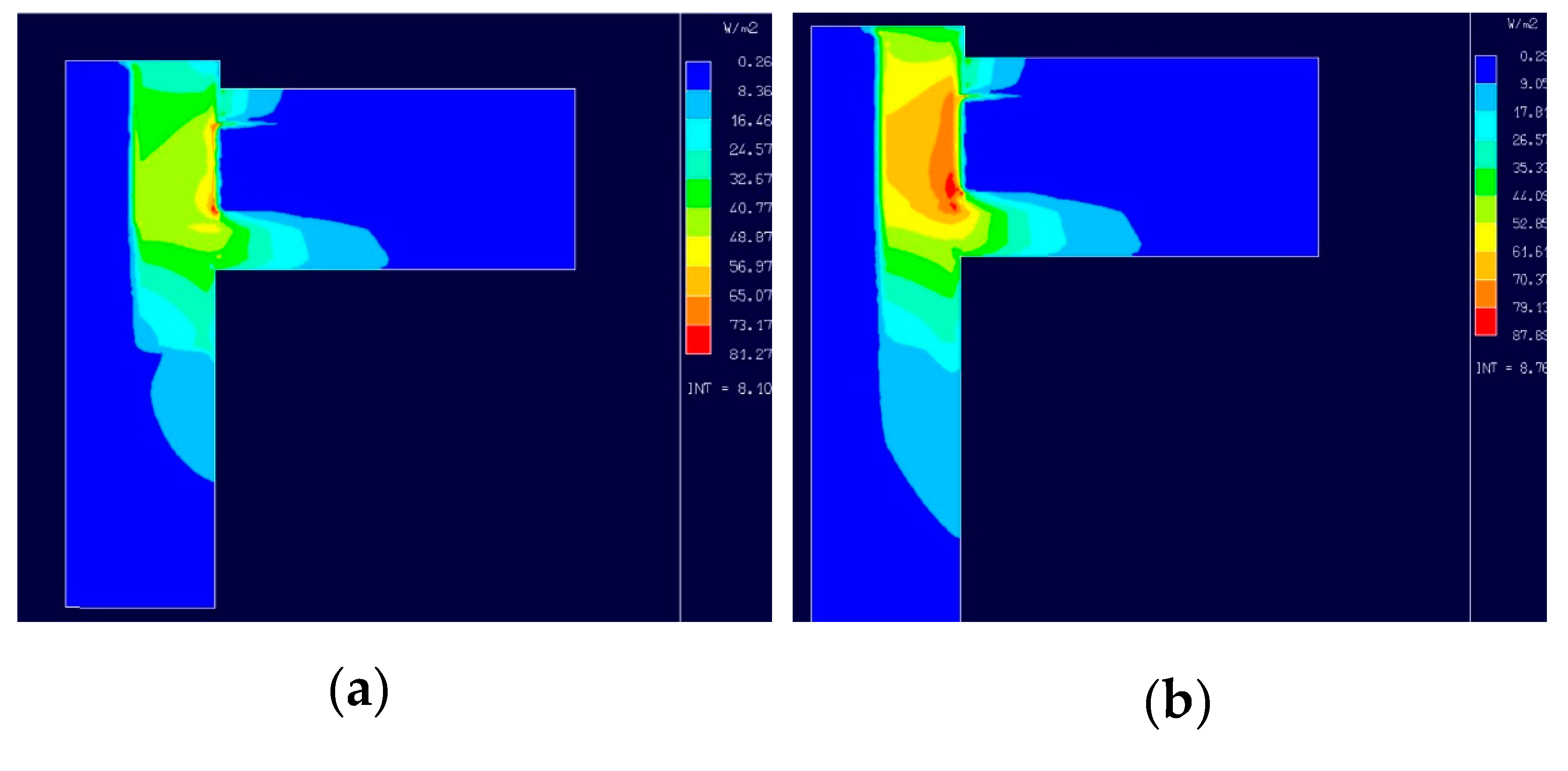

Figure 7.

The results obtained for the analyzed thermal bridge demonstrate also a positive influence on the thermal performance, comparing the values obtained for the wall panel made of clay bricks and of perlite concrete blocks. The thermal flow values show a 16% increase in the wall panel for case II, without reaching the critical values, (

Figure 7). The overall thermal resistance of the wall (R

element) with perlite concrete blocks (case II) shows a decrease of only 3% compared to the resistance of the wall made with bricks (case I).

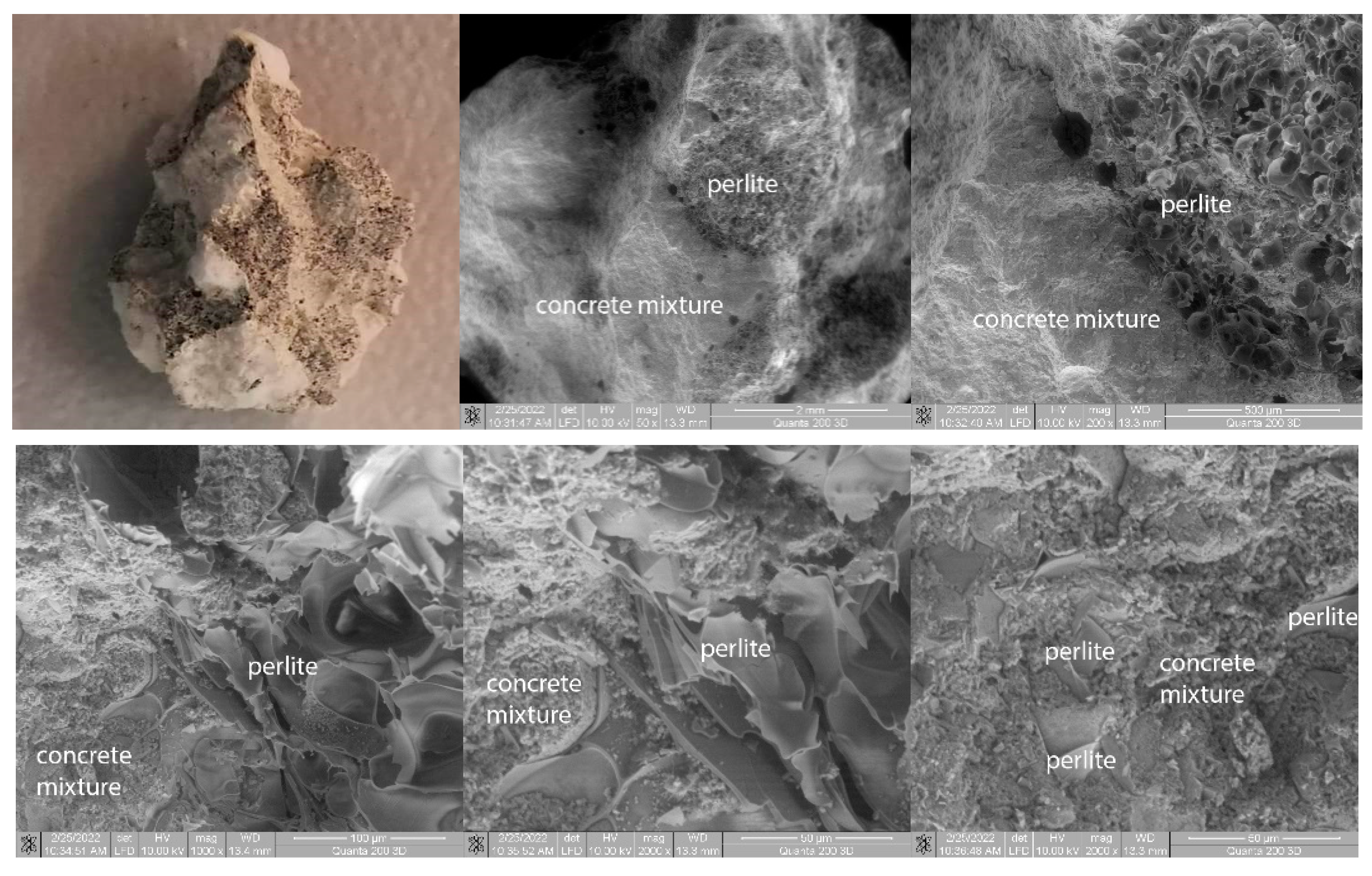

3.6. The Adhesion of the Perlite in the Concrete Composition

To ensure that the perlite particles were evenly distributed throughout the concrete mixture, special care was taken to distribute the perlite evenly while mixing the concrete in a concrete mixer. The mixture made by replacing the fine aggregate with perlite required special attention during the pouring and vibration of the molds to ensure a uniform distribution of the aggregates and achieve coagulation of the mixture. Throughout the compressive strength tests, fissure were seen in the areas of the samples with the highest concentration of perlite. However, when the samples had undergone press testing, it was observed that the perlite particles were mostly evenly arranged in the mixture. In order to investigate the bond of the perlite to the other components of the concrete mixture, 1 cm pieces of each of the compositions were examined under a microscope using a Large Field Detector in low vacuum mode (LFD). As shown in

Figure 8, the bonding between the regions with perlite and the rest of the aggregates was reasonable compared to conventional concrete.

4. Discussion

The research studies developed had the intention to present materials used for concrete mixture, which allows for improving its thermal property values.

In part 1, [

1], the crumb rubber material was used for the replacement of aggregate in concrete in percentages as 10 %, 20 %, and 30 %. The same laboratory tests were done using the perlite as a replacement for aggregate in concrete samples. In this stage of research, a low improvement in the thermal conductivity of perlite concrete was observed. In the case of the perlite replacements from 10 % to 30 %, the measurement results have varied only from 2.55 W/mK to 2.41 W/mK for heat flow parallel to the casting direction and only from 2.16 W/mK to 2.07 W/mK for heat flow perpendicular to casting direction.

Because the replacements of 10 %, 20 %, and 30% of 0-4 mm aggregate did not conduct significant improvements in thermal conductivity, the measurements made for the replacement of 100 % sand with perlite have been further discussed and analyzed in this paper. The incorporation of 100 % perlite in the concrete mixture resulted in a 15.35 % reduction in density, and a 58.30 % and 48.15 % improvement in thermal conductivity for the heat flow parallel to the casting surface and perpendicular to the casting, respectively. However, it is essential to also consider the compressive strength of the mixture when selecting a mix that improves thermal resistance, as the mixture with the highest amount of perlite (100%) had a compressive strength of 11.49 % lower than the control mixture.

The control concrete composition, class C20/25, typically used for building elements, has a minimum compressive strength of 25 MPa. Replacing perlite with up to 30 % changed the compressive strength value to class C16/C20.

However, due to the lack of significant improvement in thermal conductivity, a new set of control samples was prepared as C16/20 class concrete. The inclusion of 100% perlite resulted in a mixture classified as C12/15 (18.55 MPa), often used in prefabricated concrete blocks.

The results obtained in the linear analysis of the corner thermal bridge for the wall panel made of clay bricks (case I) and of perlite concrete blocks (case II) show that the thermal resistance of the wall with perlite concrete blocks has an insignificant decrease of approximately 3%, which substantiates the proposal for use as a prefabricated masonry element.

The bond between the pearlite-containing regions in the concrete mixture was evaluated using a microscope and was found to be comparable to that of the control concrete. This suggests that the inclusion of perlite in the mix did not have a significant impact on the bond between the concrete components, as seen on magnification. However, it is necessary to mention that the distribution of perlite granules could be affected by a low A/C ratio, the fresh workability of the concrete could affect the homogeneity of the composition.

5. Conclusions

The present study is part of a larger experimental investigation of the incorporation of two environmentally friendly materials, perlite and crumb rubber [

1], into cement-based products to enhance their thermal insulation properties and to reduce concrete environmental impact.

One of the most significant results of the current study is the improved thermal insulation property of concrete when perlite is used in the composition as a fine part of the aggregates, especially the sort of 0-4 mm. Thus, the results obtained from the conducted research show that the replacement of sand with perlite in proportions of 10, 20 and 30 percent leads to the improvement of thermal insulation properties, simultaneously with the reduction of mechanical resistance. However, these results are not in line with expected targets, the advantage obtained for the thermal performance is diminished in importance, being outranked by the decrease in mechanical resistance. The total replacement of sand with perlite, (in 100 percent), determines an obvious improvement of the thermal insulation properties, with an undoubted disadvantage of weaken the concrete, slightly under the limit of the C16/C20 concrete resistance class, more precisely class C12/15. Based on these results of the substantial decrease in thermal conductivity and density, as well as a decrease but in adequate limits in compressive strength, it can be concluded that for prefabricated concrete blocks used in non-load-bearing walls, concrete with perlite as a 100% substitute for sand, is a solution that can be used successfully, to highly increase the termal insulated performance of exerior walls. This solution has the advantage that the blocks can be made industrially, with certified quality control, and in much larger sizes than concrete blocks or ceramic bricks, considering the reduced density. Also, for one square meter of masonry made of concrete blocks with perlite, the costs can be greatly reduced, compared to one square meter of masonry made with ceramic or concrete blocks through two of its components: the cost of the raw material used and the cost of labor. This financial advantage is the result of the fact that waste perlite can be used, and the labor, as a parameter directly proportional to the built time, is reduced due to the increased size of the blocks used for a masonry wall.

The results also highlighted the ability of the concrete mix components to bond to each other, knowing that this adhesion affects the overall performance and structural integrity of the concrete. Inadequate adhesion of components can lead to internal voids or promote concrete cracking, as well as other types of degradation. According to the research results, the samples with perlite showed a good compactness, the microscopic imaging highlighting a similar volume of voids compared to normal concrete samples. The samples incorporating crumb rubber revealed a much larger void volume with a low adhesion of the rubber granules to the concrete aggregates (gravel type), probably due to the smooth surface of the recycled rubber [

1], as well as due to a low capacity to water absorption for rubber, which obstructs the formation of cement paste hardening compounds in deep contact with the rubber surface.

For a more comprehensive understanding of how the physical-mechanical properties, and, in general, the behavior of concrete subjected to different environmental factors/actions are affected by incorporating posible wastes in its compositions, further studies are needed. The design of the compositions, as well as the research of the concrete products characteristics, according to the standard quality requirements, have to take into account the influence of several variables defined as: material properties, geometry characteristics or environmental factors. The results obtained lead to the adaptation of the construction industry to a circular economy, without causing damage to the main function of the constructions, that of resistance and stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., D.N.I. and I.R.B.; methodology, A.C. and S.G.M.; software, A.C. and I.R.B..; validation, A.C., D.N.I. and S.G.M.; formal analysis, A.C. and D.N.I.; investigation, S.G.P. and I.R.B.; resources, S.G.M.; data curation, A.C. and D.N.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C., D.N.I. and S.G.P.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and D.N.I.; visualization, A.C.; supervision, D.N.I.; project administration, D.N.I.; funding acquisition, D.N.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

This paper was elaborated with the support of the “Eco-innovative Products and Technologies for Energy Efficiency in Constructions – EFECON” research grant, project ID P_40_295/105524, Program co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund through Operational Program Competitiveness 2014-2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cojocaru, A.; Isopescu, D.N.; Maxineasa, S.G.; Petre, S.G. Assessment of Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Cement-Based Materials—Part 1: Crumb Rubber Concrete. Buildings 2023, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupu, M.L.; Isopescu, D.N.; Tuns, I.; Baciu, I.-R.; Maxineasa, S.G. Determination of Physicomechanical Characteristics of the Cement Mortar with Added Fiberglass Waste Treated with Hydrogen Plasma. Materials 2021, 14, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petre, S.G.; Isopescu, D.N.; Pruteanu, M.; Cojocaru, A. Effect of Exposure to Environmental Cycling on the Thermal Conductivity of Expanded Polystyrene. Materials 2022, 15, 6921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markiv, T.; Sobol, K.; Franus, M.; Franus, W. Mechanical and durability properties of concrete incorporating natural zeolite. Arch. Civil Mech. Eng. 2016, 16, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mir, A. Influence of Additives on the Porosity-Related Properties of SelfCompacting concrete. Ph.D. thesis, Budapest University of Technology and Economics, Faculty of Civil Engineering, 2018.

- Kimball Suzette, M. Menial Commodity Summaries 2016. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey 2016; 1–1202.

- Mladenovic, A.; Suput, J.S.; Ducman, V.; Skapin, A.S. Alkali-silica reactivity of some frequently used lightweight aggregates. Cem Concr Res 2004, 34, 1809–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodeyama, K.; Sakka, Y.; Kamino, Y. Preparation of fine expanded perlite. J. Mater. Sci. 1999, 34, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbog˘a, R. , Gül, R. The effects of expanded perlite aggregate, silica fume and fly ash on the thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçu, I.B.; Isıkdag˘, B. Effect of expanded perlite aggregate on the properties of lightweight concrete. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 204, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengul, O.; Zaizi, S.; Karaosmanogu, F.; Tasdemir, M.A. Effect of expanded perlite on the mechanical properties and thermal conductivity of lightweight concrete. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, D.; Bindiganavile, V. Impact response of lightweight mortars containing expanded perlite. Cement Concr. Compos. 2013, 37, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzón, M.; García-Ruiz, P.A. Lightweight cement mortars: Advantages and inconveniences of expanded perlite and its influence on fresh and hardened state and durability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.M.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Labrincha, J.A.; Ferreira, V.M. Role of lightweight fillers on the properties of a mixed-binder mortar. Cement Concr. Compos. 2010, 32, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, H.; Yumrutas, R.; Akpolat, A. Mechanical and thermophysical properties of lightweight aggregate concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 96, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedidi, M.; Benjeddou, O.; Soussi, Ch. Effect of Expanded Perlite Aggregate Dosage on Properties of Lightweight Concrete. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 9, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirboǧa, R.; Gül, R. Thermal conductivity and compressive strength of expanded perlite aggregate concrete with mineral admixtures. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, R.; Demirbog˘a, R.; Khushefati, W.H. Effects of nano and micro size of CaO and MgO, nano-clay and expanded perlite aggregate on the autogenous shrinkage of mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 81, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Wang, L. Utilization of paraffin/expanded perlite materials to improve mechanical and thermal properties of cement mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 101, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isıkdag˘, B. Characterization of lightweight ferrocement panels containing expanded perlite-based mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 8, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Hwang, Y.Y.; Shin, D.K. Lightweight concrete produced using a two-stage casting process. Materials (Basel) 2015, 8, 1384–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoç, M.B.; Denirboga, R. HSC with expanded perlite aggregate at wet and dry curing conditions. J. Mater. Civil Eng. (ASCE) 2010, 22, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, H.; Yumruts, R.; Akpolat, A. Mechanical and thermophysical properties of lightweigh aggregate concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 96, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwattanapong, M.; Sinsiri, T.; Pantawee, S.; Chindaprasirt, P. A study of lightweight concrete admixed with perlite. Suranarre J. Sci. Technol. 2013, 20, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Türkmen, I.; Kantarci, A. Effects of expanded perlite aggregate and different curing conditions on the drying shrinkage of self-compacting concrete. Indian J. Eng. Mater. Sci. 2006, 13, 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Türkmen, I.; Kantarcı, A. Effects of expanded perlite aggregate and different curing conditions on the physical and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2378–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciu, I.-R. Contributions to the study of the green roofs. Ph.D. thesis, ”Gheorghe Asachi” Technical University, Iași, Romania, 2022, Chapter 3, 31-53.

- Baciu, I.-R.; Isopescu, D.N.; Taranu, N.; Lupu, M.L.; Maxineasa, S.G. Comparative Analysis of the Effect of Different Types of Green Roofs over the Linear Thermal Bridges. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, S. Tutorial Guide to AutoCAD 2016, 2D Drawing, 3D Modelling, SDC Publications, 2016.

- Ștefănescu, D. Hygrothermal Building Design Manual (in Romanian) ed Soc. Acad.,,Mateiu-Teiu Botez” 2012, Iasi, Romania.

- C 107-2005. Normative Regarding the Calculation of Thermic Properties of Building Construction Elements (in Romanian), Revised Edition in 2011 Instal Engs Assoc of Romania, Bucharest, Romania.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).