1. Introduction

Human sustainability in every workplace is closely connected to establishments’ quality, accessible green and blue spaces, and safeness [

1]. Incorporating natural environments in human work settings with innovative architectural designs and sustainable constructive materials plays a serious direct and indirect role in health and well-being. [

2]. Although it has long been understood that green working settings address an important role in both human and ecosystem health, it has only been in recent times that these relationships have been specifically investigated to adapt sustainability planning and land use to several social and environmental challenges, such as urban deprivation, biodiversity loss, pollution, and climate change [

1,

14]. Human-centric designs for built environments enhance their occupants’ satisfaction, health and emphasize sustainable lifestyles [

14,

15].

It is well documented that materials and energy resources in every sector of human activities are diminishing, or they are consumed at a faster rate than they can be replenished. [

11]. Actions have been already taken to discuss issues of green establishments that connect a sustainable physical setting with smart use of construction materials and esthetics to provide workplace environments that support human and nature’s resources [

3]. Professionals and governments worldwide have been discussing since the beginning of this century, a circular rather than linear flow of energy and materials in every field of the economy to sustain resources [

7]. The “Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe” claimed that greater efficiency in the use of resources is critical not only for environmental reasons but also for competitiveness, employment and resource security and human development [

4]. It was further highlighted that functional, safe, and high-quality products, should be provided to be more efficient, affordable, last longer, and be designed for reuse, repair, or high-quality recycling. The philosophy of four R’s (reuse, repair, rethink, recycle) or “waste hierarchy” as it is called was incorporated in various ways in CE national legislations [

8]. In March 2020, the European Commission adopted the new Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP). It is a part of the European Green Deal, Europe’s new agenda for sustainable growth [

5]. It is estimated that the EU’s transition to a circular economy will reduce pressure on natural resources and will create sustainable growth and jobs. It is also a prerequisite to achieve the EU’s 2050 climate neutrality target and to halt biodiversity loss [

5].

Under this scope green dental issues and circular philosophy in dentistry are emerging in the research literature to provide knowledge and tools for information sharing and enhancing environmental actions [

6,

9]. A big discussion is on the field to provide better quality and sustainable dental services with new processes and slow dentistry workflows in an esthetic, naturally designed environment, digital solutions, innovative resource analysis and building constructions that guarantee less waste, upgraded knowledge and skills, and, in the end, provide better quality of life for all stakeholders, up to 2050 [

5]. As in other fields, also in dentistry, the physical setting is linked to an employee’s ability to physically engage with the workplace [

13]. Since there are interconnections between buildings ‘design and people’s psychology (Yang & Yuan2022), the healthy dental workplace atmosphere has a positive impact on individual employees’ behavior [

14], motivation, enthusiasm, creativity, and efficiency [

15] or oppositively, on their willingness to quit [

9,

16]. Thus, green buildings design and construction is the new research appointment for human’s wellbeing and resources sustainability issues in the health sector [

2].

The World Green Building Council defines the green building as the building that “in its design, construction or operation, reduces or eliminates negative impacts, and can create positive impacts, on our climate and natural environment” [

10]. Stakeholders in the construction industry are focusing on making modern buildings and their internal systems more sustainable by saving energy, water and human working hours and resources [

23]. This attitude has positive environmental impacts such as reduced carbon emissions, water and energy efficiency, use of natural sunlight, exposure to nature, clean air circulation, reduced noise impact, higher returns in operating costs over 5 years, and higher investment returns [

19,

20] with an asset value that can reach 7% [

10]. These constructions can entertain healthy dental enterprises in eco-friendly offices that focus on indoor air and water quality, ability to socialize in a relaxing environment with friendly use of recycle materials, ability to exercise in the building due to long hours of continuing work, lighting and acoustics quality, safe waste disposal and security issues [

2].

So far very little is known about the behavior of dental professionals and their willingness to adapt to this sustainable office design and culture, the possible factors influencing their choices on green buildings issues or four R’s philosophy. In this study we evaluate the knowledge and attitudes of dental students and professional dentists in Greece, regarding Environment Sustainability in Dentistry (ESD), the presence of ESD in dental curricula, barriers, and enablers to embracing ESD in continuing education systems and estimated factors influencing their choices and knowledge on circular economy in the dental office.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey using piloted online questionnaires for students and den-tists was carried out at the Dental School of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. One digitally formed questionnaire designed in google forms were distributed to undergraduate dental students attending the clinical program at the dental school of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece (

Appendix I). The completion took place during April and May 2022. The students were voluntarily filling in the form. 12-15 minutes were needed to complete the form. They had not heard anything about the issues addressed in the questionnaire before in their curricula. All students were given the same access and the same opportunity to complete the questionnaire. Dentists had a different questionnaire to fill in (

Appendix II). The link to dentist’s questionnaire was sent twice within a period of twenty days through the main secretariat of the Association email address. No reward was given for participating in the study, in any of the participants.

A panel of 3 professors confirmed the validity of the questionnaires, all experts on dental education and members of the school's curriculum committee. They reviewed and revised the survey questions to be relevant to the topic and expressed correctly. They worked independently and then in two joint meetings with the authors to make final suggestions. The questionnaire was further validated through fulfillment of ten members of the academic staff and ten postgraduate students that were not involved in the study. Finally, the accuracy of the completion was checked by making all questions obligatory to submit the questionnaire while submission was only allowed once.

The online questionnaire included a short introductory message describing the purpose of the study and stressing voluntary participation, confidentiality, and the right to refuse participation. Consent was obtained by asking participants to confirm that they agreed to complete the questionnaire by marking a "Yes, I agree to participate” box. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Board of the dental school, and the study proposal was registered under the number 39521/20-4-2022. Accordingly for participating dentists, members of the Dental Association of Attica, metropolitan area of the capital, Athens the relevant license was obtained by the scientific committee of the Association (No:2660/08.12.2022). A different QR code was assigned to each questionnaire link to provide direct access through participants‘ smartphones.

Data analysis included descriptive statistics and thematic analysis. The first part of the questionnaire collected information on demographic characteristics of each sample and their experiences and practices regarding green dentistry and circular economy actions applied so far. The second part of the questionnaire was similar to both questionnaires and invited the participants to take a position on the importance of various factors that in their opinion affect circular economy issues and the creation of modern ecological dental structures (environmental beliefs) based on relevant litarature. (12-18) In this section of the questionnaire, participants expressed their views in terms of a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = "extremely insignificant", 2= "relatively insignificant", 3= "neutral", 4= "important" and 5= "extremely important". The third part of the questionnaire was also similar in both questionnaires and contained open-ended questions where they could briefly leave their opinions and suggestions on the topic.

In the statistical analysis the frequency distribution of all variables was examined (demographic information and ESD factors). Gender (males/females) and place of residence (urban/rural) as dependent variables were cross tabulated with a series of independent variables on knowledge, perceptions, and importance of factors on ESD to assess the presence of a statistically significant relationship with the chi square test and post hoc testing at the 95% significance level. All analyses were performed using the statistical software IBM SPPS Statistics (v.26) predictive analytics software.

3. Results

A total of 93 dental students attending the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th undergraduate years of studies participated in the study out of 520 (response rate 17,88%) and 126 dentists out of the 6500 members of the association (response rate 1.94%).

In the sample of dental students who participated in the survey (N1=93), 34 (36.6%) were men and 59 (63.4%) women. The distribution according to semester of studies was as follows: 60 (64.5%) students were currently attending their 4th semester of studies (2nd year), 21 (22.6%) their 6th semester (3rd year), 5 (5.4%) their 8th (4th year) and 7 (7.5%) were in their 10th semester (5th year). The majority lived in Athens or other urban areas, 61 students, (65.6%) compared to 32 students who live in rural areas or on the islands of Greece (34.4% of the total sample). Regarding the distribution of the practicing dentists in the study sample (N2=126), 46 (36.5%) were men and 80 (63.5%) were women, 96 (76.2%) resided and practiced dentistry in Athens or other urban areas and 30 (23.8%) in rural areas in Greece.

Table 1.

With regards to questions on recycling, voluntary participation to environmental protection activities and knowledge of the EU legislation on mercury (Hg) use and plastic recycling within the dental practice areas, the responses were analyzed by gender, and by place of residence.

Using gender as the dependent variable, most of the students declared practicing recycling at home, 27 (79.4%) men and 48 (81.4%) women (p=0.16). In terms of participating in voluntary activities towards environmental protection, 19 (55.9%) men and 35 (59.3%) women participants gave an affirmative answer but there was a 40% (38 respondents) in both genders who did not participate in any such activities (p=0.41). Regarding the knowledge on the contents of circular economy in the dental practice, the majority admitted lack of knowledge (76.5% in men and 62.7% in women, p=0.22). Similarly, the majority did not know the EU’s legislation regarding the use of mercury (Hg) nor on plastic recycling in the dental practice, 22 (61.8%) men, 39 (66.1%) women (p=0.57) and 27 (79.4%) men and 44 (74.6%) women (p=0.54) respectively. (Data not shown).

Similarly to the group of dental students, using gender as the dependent variable, most of the practicing dentists were not informed on the meaning of circular economy (68.3%, 86 out of the 126 respondents, p=0.24) neither on the EU regulations regarding mercury use (58.7%, 74 out of the 126 respondents, p=0.36) and plastic use and recycling in the dental practice (76.9%, 97 respondents, p=0.49), although 40 men and 64 women dentists (86.9% and 80% of the total study participants respectively) declared that they recycle at home and they participate in voluntary environmental activities (84 respondents, 66.7%). (Data not shown).

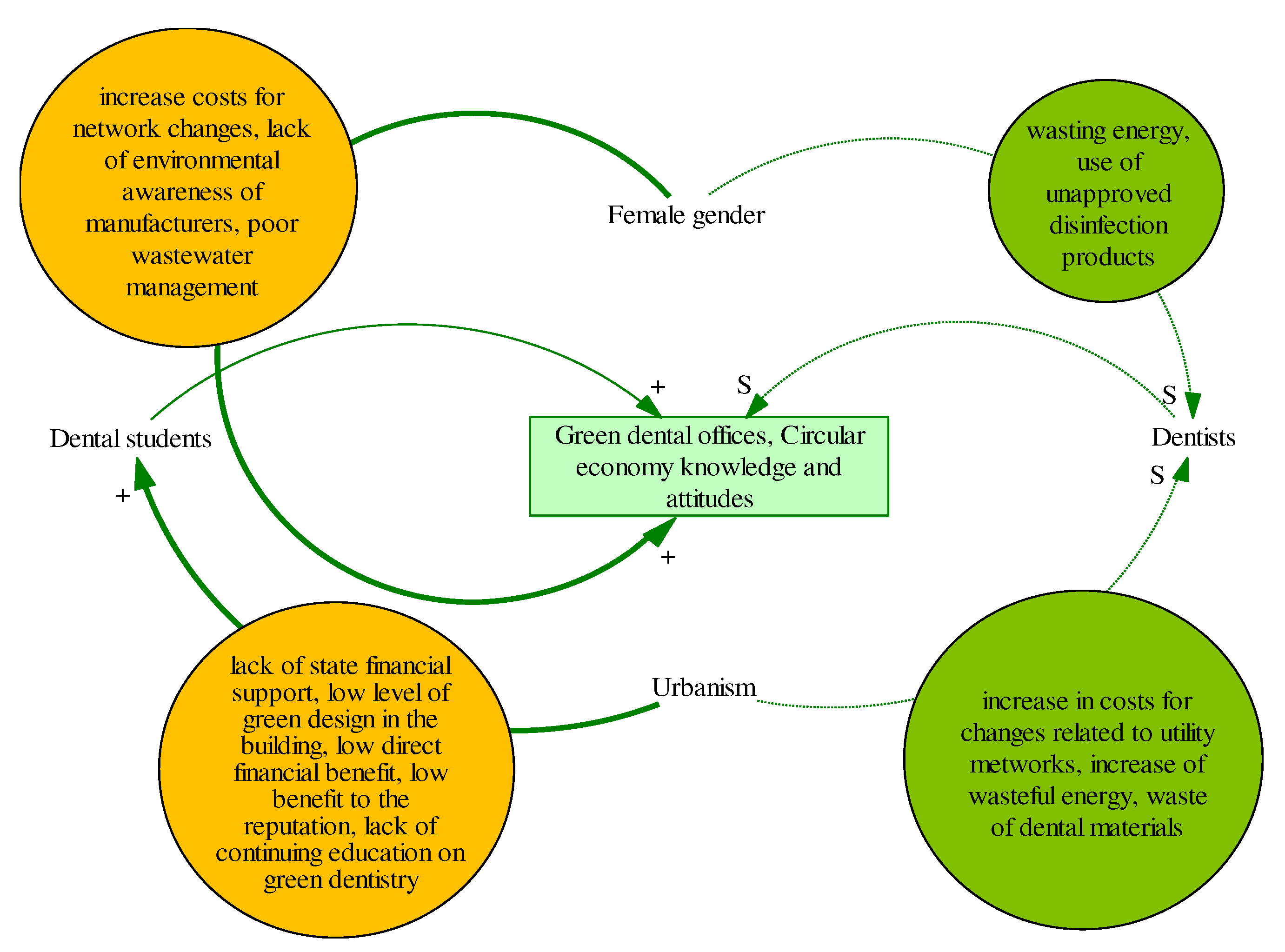

In the analysis of perceptions of dental students regarding factors related to the green dental practice, there seem to be a statistically different perception between male and female students with regards to the increased costs required to make the necessary changes in utility networks (services like electricity, natural gas, or water) (p=0.02), the reduced environmental conscience of building contractors (p=0.057) and the poor wastewater management systems (p=0.01) with female students being more prone to answer positively as “very important”. No significant relationships were observed in the study sample of the practicing dentists on the level of importance of factors related to the green dental practice by gender. The practicing dentists were also asked to name the most environmentally damaging practice in a dental practice with wasteful energy (p=0.024) and the use of unapproved disinfection products (p=0.036) being the most important but not statistically significant ones (

Table 2).

In the analysis of perceptions of dental students and practicing dentists using place of residence as the dependent variable, there seems to be a statistically different perception in the group of dental students between residents in urban areas compared to residents of rural areas with regards to the level of importance of the “lack of state funding” (p=0.02), the “low level of green design in buildings” (p=0.03), the “low benefit for the reputation of the green dental practice by today’s standards” (p=0.02) for those practicing in urban areas, the “reduced profit of a green dental practice in the immediate future” (p=0.04) and the “lack of continuous education seminars on green dentistry” (p=0.05) for those practicing in rural areas (

Table 3). No statistically significant relationships were observed in the group of dentists regarding the level of importance of the most significant factors in green dental practices by place of residence, with only a weak relationship for the “increased in costs for changes related to utility networks” (p=0.08). (

Table 3)

However, it is interesting to note that high proportions of the responding dentists declared several of these practices as being non-significant or neutral, namely “lengthening the construction time of a green dental practice” (49.2%, p=0.56), “increased necessary and mandatory space required” (46%, p=0.31), “reduced benefit for the reputation of the business by today’s standards” (45.3%, p=0.26) or “not visible financial benefit in the near future” (43.6%, p=0.44). An interesting finding is the perception of 88 dentists (69.8%) on the great “importance of lack of knowledge of green dentistry” (p=0.66). (Data not shown).

In the question to practicing dentists to identify the most environmentally damaging practices in a dental practice by place of residence, weak relationships were observed with “increased wasteful energy” (p=0.12) and “waste of dental materials” (p=0.19). (Data not shown).

A combined diagram of the relationship between urbanism and gender with environmental attitudes and knowledge for students and dentists can be seen in

Figure 1.

Finally, the study participants were asked to propose changes to promote eco-friendly dentistry in the undergraduate course curriculum. From the dental students, the addition of seminars, short courses or essay assignments on environmental protection practices was mentioned, on the principles of green dentistry, and on ways to efficiently run a dental practice. The courses can be compulsory or optional, preferably available across the 5 years of the dental study course span to enable participation from many dental students in different stages of their educational program.

According to the dental student respondents, students lack knowledge on environmental protection principles, practices, and approaches, such as the circular economy and motivation to establish green dental practices. On-site visits to green dental practices were also proposed to provide a hands-on experience for junior dentists.

Proposals from students towards the implementation of eco-friendly practices within the dental practice included the use of biodegradable materials, the use of solar power or renewable sources to cover the energy demands, ways to reduce the amount of dental waste and to increase recycling along with familiarization with the corresponding legal framework, state financial support and financial incentives to create green dental practices.

The participating dentists proposed seminars or short courses during undergraduate studies to increase the ecological conscience of future dentists. With regards to proposals for the future of green dentistry, the use of energy saving practices, renewable energy source use, biodegradable dental materials and guidelines on plastic recycling and waste management practices were mentioned.

4. Discussion

In this cross-sectional study dental students and practising dentists participated to provide information on their level of knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes on environmental sustainability in dentistry and help identify barriers and enablers in behaviours concerning green buildings for dental offices in Greece. As reported elsewhere, the green building market share is still very small due to extra costs incurred from materials, design, and technology issues [

20,

21]. Despite the numerous benefits associated with green constructions, the issue of upfront cost is a frequently cited obstacle which precludes the widespread adoption of green buildings [

17,

18,

19,

21] a fact justified also from our data. The costs of the green buildings were reported to be from 1.84% higher on average, almost a decade ago [

20] to almost 20% in more recent studies [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Economic reasons concerning implementation of green construction and function of dental offices could explain the low response rate in our study and the non-significance value according to participants of most of the factors related to green dental practice either by gender or area of residence. It is a fact that after the Covid-19 pandemic, dentistry became more expensive and professionals seem reluctant to shoulder another increase in practicing dentistry that will include construction or energy changes [

7,

26]. Urbanism seems to play an important role for students and a weak but not statistically important one for professional dentists as far as it concerns environmental philoshophy and its economic consequences. The findings can be explained by the fact that practicing dentistry in urban areas seems to be more expensive and demanding due to the cost of transportation and trafficking and the bigger dental offices reported from our data, mentioned also elsewhere [

7,

8]. The waste of dental materials for dentists in urban centers is the most sensible matter since they seem to practice more expensive dentistry and this has economic consequences that harvest their income.

In the green building movement, as already described, more than half of the construction costs consist of green features, such as alternative systems, applications, and materials, which are converted into credits under the green building rating system offering value to it [

22]. Except of the construction costs there are also soft costs, including certificate application, approval, consultancy and commissioning and additional design costs. The extra cost significantly handicaps the large-scale adoption of green buildings [

24] as reported from our data too.

Furthermore, an interesting finding in our study is the fact that both students and practising dentists, revealed a lack of knowledge on the topics of circular economy, EU regulations on mercury use and plastic recycling in the dental practice, in almost similar percentages, which contrasts with the declared use of recycling at home and their voluntary participation in environmental protection activities. Possibly this is since recycling at home has long been established through relevant state campaigns. This attitude is not followed in the workplace where lack of time at the end of the working day disables employees to perform it [

8]. Although not statistically important, men seem to be more informed on environmental terms and legislation while women are those who participate more in voluntary actions. Gender differences in environmental attitudes are also discussed elsewhere with women recently catching up men in volunteering and engage in more altruistic voluntary activities. [

27] Participation in voluntary work may be associated with individual and societal benefits. Factors such as socioeconomic status, being married, social network size, church attendance and previous volunteer experiences [

28] are positively associated with volunteering while age, functional limitations and transitions into parenthood are discussed as being inversely related to volunteering [

29] possibly due to lack of time and demands from the emerging roles. Furthermore, green voluntarism is inversely related to mortality [

30,

31] depression [

31,

32,

33] functional limitations [

32], and positively related to self-rated health in adults and children [

34,

35]. Thus, green voluntarism should be enhanced among dental professionals to enhance the social profile of dentists as well as their well-being.

Over 60% of the dentists in our study lack knowledge on environmental legislation concerning circular economy, disposal of amalgam and recycling plastics which is a high percentage that dental associations and dental authorities should take into consideration for future educational campaigns. Six out of ten dentists in our study do not know the legislation for disposal of amalgam, seven out of ten about circular economy and eight out of ten about recycling of plastics. Those professionals should have certain ethical motivation to fulfill environmental strategies if we seek current acceptance and correspondence to new environmental steps and laws. Economic motivation alone as explained elsewhere will not provide the expected results since providing monetary incentives can activate a processing mode that is transactional, money can prime mental constructs incompatible with sustainable behaviors, and monetary incentives can signal that money is the reason that one is engaging in the target action. [

28,

36]

Another interesting finding of our study is the perception from two out of five dentists (34.9% of the respondents) that the lack of seminars and education on green dentistry is neutral or less important to them. On the other hand, students were more sensitive in acquiring knowledge on these issues than practising professionals. This is also characteristics of their generation as mentioned elsewhere [

37,

38]. With regards to the most significant factors in green dental practices the group of dental students identified increased costs in utility networks, lack of environmental awareness of the building contractor and poor wastewater management whereas the dentists did not identify any significant factors when examined by gender. Further, when examined by place of residence and probably place of dental practice, dental students declared lack of financial support, low level of green design in buildings, reduced profit of the dental practice, low benefit of the reputation and lack of continuous education seminars on green dentistry enhancing more their sensitivity on the matter as discussed elsewhere [

37,

39,

40,

41]. The proposals by both groups in our study, point to the need of introducing modules in the undergraduate course of dental studies on the principles of green dentistry and on guidance on how to run a sustainable dental practice. Students were quite thorough in proposing ways of delivering such courses (e.g. seminars, essay writing), available throughout the five years of undergraduate program, whereas practising dentists were a lot more conservative in this aspect and mostly suggested that such courses should be offered to students or junior dentists and not themselves. From our data we can suggest that certain behaviors having significant negative environmental impacts should be part of future information campaigns to improve environmental culture of Greek dental professionals as mentioned already elsewhere [

42,

43,

44]. An assessment baseline level of target behaviours should be further examined in a future sample after information sharing through social media and continuing educational projects from universities and dental associations. Finally, dental associations should assess the long-term feasibility of behaviour changes of their members.

Consequently, factors determining the relevant behaviour in our study are gender, urbanism, perception of costs and benefits, habits based on lack of information, time management, economical status and ethics, as also discussed elsewhere [

45]. Interventions that could best be applied to encourage environmental behaviour are informational strategies (information, persuasion, social support and role models, public participation in voluntary actions designed by dental or health state authorities) and structural strategies (availability of products and services, low cost of recycling cleaning products, legal regulation, financial strategies) [

36]. The expected effects from such interventions can be changes in behavioural determinants, changes in behaviours (purchasing, using, refilling), changes in environmental quality and changes in individuals' quality of life (changing purchasing behaviour generally has greater environmental benefit than reusing or recycling available products [

39,

40]. As it is proposed, to design effective interventions to modify habitual environmental behaviour, it is important to consider how habits are formed, reinforced, and sustained

[43,44,45,46,47]. Dental authorities and energy companies should play an important role in rewarding green practices and thus cultivate green motivation among professionals to change habits, improve motivations, perceptions, cognitions, and norms while structural state strategies, should aim at changing the circumstances under which behavioural choices are made [

14,

38,

41,

42,

48].

5. Conclusions

The analysis by place of residence and practising dentistry indicates some functional obstacles in the establishment of environmental sustainability such as lack of financial support, low level of green design in buildings and increased costs for utility networks which are obviously linked to difficulties in sustainable urban design regulations and limited financial support to create an eco-friendly practice. Dental students seem to be more engaged in identifying ways to increase the access to new information on environmentally sustainable dentistry, green buildings that host modern dental offices and to improve their eco-employment prospects. Practising dentists on the other hand, seem more set in their ways, appear less engaged with the prospect of switching to environmentally sustainable practices in dentistry and less interested in participating in continuous education activities compared to students. Introducing the topic of Environmentally Sustainable Dentistry (ESD) in the undergraduate dental course curriculum is vital to provide the necessary knowledge to new generations of dentists and to enable the implementation of a series of sustainable practices in dentistry by choice and not merely as adherence to guidelines and regulations. The corresponding changes in policies and regulations when setting up a dental practice need to follow the environmentally sustainable requirements along with regularly updated guidance on changes and new developments in the field. Facilitators such as funding opportunities and user-friendly administrative procedures will greatly favour the shift to establishing more green dental practices in the future. Although green dentistry is an interesting marketing tool for all health professionals in public or private sector there is need for additional guidelines, tools, techniques, and state support to share common environmental beliefs of limits to growth and eco-crisis.

6. Limitations

This study has certain limitations. The data about factors influencing willingness to pay for green dental buildings and green use were mainly based on factors mentioned in other studies [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] and not on specific factors existing in the contsruction industry in Greece. There is a lack of experimental elements which could more rigorously assess the willingness and practice of the specific sample as reported elsewhere too [

48,

49,

50]. Because of this limitation, behavioral results should be further assessed to link specific green building elements and technologies with the sensitive environmental behaviors of this study. The need for more evidence to inform the green health building movement in Greece, is obvious. A future study should also adopt experimental methods to observe users’ behaviors and their willingness to cooperate on green dental philosophy and culture or address different motivators and facilitators. Figuring out the spending power and resources of the respondents on green materials and buildings is also required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.; methodology, M.A.; software, E.R.; validation, M.A. and E.R.; formal analysis, E.R.; investigation, M.A, G.C. and R. T; resources, M.A, G.C. and R. T; data curation, M.A and E.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A., G.C., R. T., and E.R. writing—review and editing, M.A., and E. R.; visualization, M.A.; supervision, M.A.; project administration, M.A.; funding acquisition, M.A and E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly financed by the Specific Account for Grant Research of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (ELKE). The funding source was not involved in the study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Dental School of Athens (39521/20.04.2022) and the scientific committee of the Dental Association of Attica, metropolitan area of Athens, Capital of Greece (no: 2660/08.12.2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained by filling the questionnaire.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank all participants filling up the questionnaires of the study and Ioannis Tzoutzas for his help in obtaining the license from the scientific and directive committee of the dental association of Attica to address this issue to members.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

Environmentally Sustainable Dentistry (ESD)

Appendix I. The questionnaire for dental students

INTRODUCTORY MESSAGE

Dear colleagues,

This online survey is aimed to gather information on environmental attitudes, circular economy issues and green sustainability in construction and use of green dental offices, in Greece. It also aims to verify factors that influence response to these issues and give proposals for future effective educational approaches to the matter. The participation in the study is voluntary and no personal data is gathered. You have the right to refuse participation. No reward is given for your participation. You may confirm that you agree to complete the questionnaire by marking the box "Yes, I agree to participate”. The access to the questionnaire is only opened once. All questions must be filled in to submit the form. Ethical approval is obtained from the Ethics Board of the dental school, and the study proposal is registered under the number 39521/20-4-2022.

Part A. Demographics:

1.What is your gender; male, female, other

2. Which semester of study do you attend?; 4o, 6o, 8o, 10o semester of undergraduate studies

3. Where your family lives; Capital, Other urban city, mainland, Island periphery, abroad

4. What is the highest educational level of the family as a whole (refer to the parent who has the highest level of education); elementary, Gymnasium/Lyceum, College, University

5. Do you use recycling in your home; Yes No I don't know/I don't answer

6. ‘Have youever participated in voluntary environmental protection actions in the area where you live with your family or during your studies? Yes NoI don't know/don't answer

7. Are you aware of what the circular economy includes in the pieces related to the dental office?

Yes, No, I don't know/I don't answer

8. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation on the use of mercury in dental practice?

Yes, No, I do not know/I do not answer

9. Are you aware of the current legislation of the European Union on the use and recycling of plastic in the dental office? Yes, No, I do not know/I do not answer

10. Evaluate the following factors depending on the importance you think they have in creating a green dental office (note which one expresses you the most) 1: Extremely trivial, 2: Relatively insignificant, 3: Neutral, 4: Important, 5: Extremely Important

10.1. Lack of regulations and national legislation

10.2. Lack of state control

10.3. Lack of specific technical knowledge and support during the construction of the building where the dental office is located

10.4. Lack of specific technical knowledge and support during the design of the dental office

10.5. Lack of financial support

10.6. Low level of "green design" in buildings

10.7. Lengthening the construction time of a green dental office

10.8. Increase in costs for related changes to utility networks

10.9. Increase the necessary and mandatory space for a dental office

10.10. Higher cost of buying / renting a "green" business space

10.11. Possible damage to the structure of the buildings if the changes for the green dental office are made after the construction

10.12. Lack of mature knowledge about the green construction of buildings and in particular dental clinics

10.13. Immature purchase of green materials for the construction of green health structures

10.14. The economic benefit is not visible in the near future

10.15. Questions and doubts of the public/patients about the safety of green materials for the construction of health structures

10.16. Low demand for green buildings

10.17. Lack of environmental awareness of manufacturers

10.18. Lack of environmental awareness of the public

10.19. Lack of advertising for green dental structures

10.20. Lack of training on green dentistry

10.21. Waste of water inside the dental office

10.22. Poor wastewater management

10.23. Incomplete management of household waste

10.24. Cost of septic waste collection

10.25. Cost of air purification devices

10.26. Reduced application of renewable energy sources in the city

10.27. Reduced application of renewable energy sources in the dental office

10.28. Low benefit for the reputation of the business by today's standards

10.29. Lack of general instruction of professional associations for recycling paper and plastic within the dental office

10.30. Lack of continuing education training seminars on green dentistry

11. Note your suggestions for ecological dental education ………

12. Note your suggestions for the green dental office of the future ……..

Appendix II. The questionnaire for dentists

INTRODUCTORY MESSAGE

Dear colleagues,

This online survey is aimed to gather information on environmental attitudes, circular economy issues and green sustainability in construction and use of green dental offices, in Greece. It also aims to verify factors that influence response to these issues and give proposals for future effective educational approaches to the matter. The participation in the study is voluntary and no personal data is gathered. You have the right to refuse participation. No reward is given for your participation. You may confirm that you agree to complete the questionnaire by marking the box "Yes, I agree to participate”. The access to the questionnaire is only opened once. All questions must be filled in to submit the form. Ethical approval is obtained from the Dental Association of Attica, scientific committee of the Association (No: 2660/08.12.2022).

Part A. Demographics:

1.What is your gender; male, female, other

2. Which semester of study do you attend?; 4o, 6o, 8o, 10o semester of undergraduate studies

3. Where your family lives; capital, other urban city, mainland, island periphery, abroad

4. Do you use recycling in your home? Yes, No

Q5. ‘Have you ever participated in voluntary environmental protection actions in the area where you live with your family or during your studies? Yes, No, I do not know/I do not answer

Q6. Are you aware of what the circular economy includes in the dental field? Yes, No, I do not know/I do not answer

Q7. Are you aware of the current European Union legislation on the use of mercury in dental practice? ? Yes, No, I do not know/I do not answer

Q8. Are you aware of the current legislation of the European Union on the use and recycling of plastic in the dental office? ? Yes, No, I do not know/I do not answer

Q9. What is the most environmentally damaging behavior for you in a dental office?

Q9.1. The collection of septic waste along with household waste

Q9.2. The absence of application of documented antisepsis protocols

Q9.3. Noise production

Q9.4. Wasteful energy

Q9.5. Wasting water

Q9.6. The waste of dental materials

Q9.7. The use of non-recyclable single-use products

Q9.8. The use of unapproved disinfection products

The rest of the questions were as described for questionnaire in

Appendix I.

References

- WHO. Green and New Evidence and Perspectives for Action Blue Spaces and Mental Health. Accessed on 26 March 2023 from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/342931/9789289055666-eng.pdf.

- Cvenkel N. Well-being in the workplace: governance and sustainability insights to promote workplace health. On Approaches to global sustainability markets and governance. Springer 2020. [CrossRef]

- EC (2011a) A resource-efficient Europe – flagship initiative under the Europe 2020 Strategy. COM 21.

- EC (2011b) Road map to a more resource efficient Europe. SEC 1067.

- EC (2020). New circular economy action plan. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/circular-economy-action-plan_en.

- FDI. Consensus statement. Consensus on Environmentally Sustainable Oral Healthcare: A Joint Stakeholder Statement. Accessed 26 March 2023 from https://www.fdiworlddental.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/Consensus%20Statement%20-%20FDI.pdf.

- Antoniadou M, Varzakas T, Tzoutzas I. Circular Economy in Conjunction with Treatment Methodologies in the Biomedical and Dental Waste Sectors. Circ.Econ.Sust. 2020, 1, 563–592 (2021a). [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou M. Economic survival during the COVID-19 pandemic. Antoniadou M. Oral Hyg Health 2021b, 9:1, 267-269. https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/economic-survival-in-the-covid19-pandemic-era.pdf.

- Antoniadou, M. Quality of Life and Satisfaction from Career and Work–Life Integration of Greek Dentists before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 9865. [CrossRef]

- Di Noto J. Healthy Buildings vs Green Buildings: What’s the Difference? December 16, 2021, Accessed 23 March 2023 from https://learn.kaiterra.com/en/resources/healthy-buildings-vs-green-buildings-difference.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). IPCC 5th Assessment Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Allen, J.G., MacNaughton, P., Laurent, J.G.C. et al. Green Buildings and Health. Curr Envir Health Rpt 2015 2, 250–258 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Scrima F, Mura AL, Nonnis M, Fornara F. The relation between workplace attachment style, design satisfaction, privacy and exhaustion in office employees: a moderated mediation model. J Environ Psychol. 2021, 78:101693. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, The Cong P, Sanyal S, Suksatan W, Maneengam A, Murtaza N. Insights into rising environmental concern: prompt corporate social responsibility to mediate green marketing perspective. Econ Res Istra Živanja. 2022, 1−17. [CrossRef]

- Zhenjing G, Chupradit S, Yen Ku K, Nassani A, Haffar M. Impact of Employees' Workplace Environment on Employees' Performance: A Multi-Mediation Model. Front. Public Health, 2022, 10-2022 Sec. Occupational Health and Safety, . [CrossRef]

- Markey R, Ravenswood K, Webber D. The impact of the quality of the work environment on employees’ intention to quit. Economics Working Paper Series 1220, University of west England. Accessed on 26 March 2023 from https://www2.uwe.ac.uk/faculties/BBS/BUS/Research/economics2012/1221.pdf.

- Van Schaack C, BenDor T A comparative study of green building in urban and transitioning rural North Carolina. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2011, 54, 1125–1147. [CrossRef]

- Tsai WH, Yang CH, Huang CT, Wu YY. The impact of the carbon tax policy on green building strategy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 1412–1438. [CrossRef]

- Kats, G, Alevantis, L, Berman, A, Mills, E, Perlman J. The Costs and Financialbenefits of Green Buildings. A Report to California’s Sustainable Building Taskforce; Capital E: Wellington, New Zealand, 2003.

- Kats, G. Greening Our Built World: Costs, Benefits, and Strategies; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Langdon, D. The Cost & Benefit of Achieving Green Buildings; Davis Langdon Management Consulting: London, UK, 2007.

- Jin-Lee, K, Martin, G, Sunkuk K. Cost Comparative Analysis of a New Green Building Code for Residential Project Development. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2014, 140. [CrossRef]

- Dwaikat LN, Ali KN. Green buildings cost premium: A review of empirical evidence. Energy Build. 2016, 110, 396–403. [CrossRef]

- Darko, A, Zhang C, Chan APC. Drivers for green building: A review of empirical studies. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 34–49. [CrossRef]

- Ma C, Rogers AA, Kragt ME, Zhang ,; Polyakov, M, Gibson F, Chalak M, Pandit R, Tapsuwan S. Consumers’ willingness to pay for renewable energy: A meta-regression analysis. Resour. Energy Econ. 2015, 42, 93–109. [CrossRef]

- ADA. COVID-19 Economic Impact on Dental Practices. March 2015. Accessed 2 April 2023 from https://www.ada.org/resources/research/health-policy-institute/impact-of-covid-19.

- OECD. Women are catching up to men in volunteering, and they engage in more altruistic voluntary activities. Accessed 2 April from https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/women-are-catching-up-to-men-in-volunteering-and-they-engage-in-more-altruistic-voluntary-activities.htm.

- SMU, Singapore management university. Why rewarding sustainable behaviour with money is a bad idea By SMU City Perspectives team. Published 9 May, 2022. Accessed 2 April from https://cityperspectives.smu.edu.sg/article/why-rewarding-sustainable-behaviour-money-bad-idea.

- Niebuur, J., van Lente, L., Liefbroer, A.C. et al. Determinants of participation in voluntary work: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1213. [CrossRef]

- Okun MA, Yeung EW, Brown S. Volunteering by older adults and risk of mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:564–77. [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson CE, Dickens AP, Jones K, Thompson-Coon J, Taylor RS, Rogers M, et al. Is volunteering a public health intervention? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the health and survival of volunteers. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:773. [CrossRef]

- Anderson ND, Damianakis T, Kröger E, Wagner LM, Dawson DR, Binns MA, et al. The benefits associated with volunteering among seniors: A critical review and recommendations for future research. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:1505–33. [CrossRef]

- International Labour Office Geneva. Manual on the measurement of volunteer work. Geneva: International Labour Office (ILO); 2011. p. 1-120. ISBN 978-92-2-125071-5. www.ilo.org/publnsI.

- Salamon LM, Sokolowski SW, Megan A, Tice HS. The state of global civil society and volunteering: latest findings from the implementation of the UN nonprofit handbook, Work Pap John Hopkins Comp Nonprofit Sect Proj, 2013, 49, 18.

- Patrick R, Henderson-Wilson C, Ebden M. Exploring the co-benefits of environmental volunteering for human and planetary health promotion. Health Promot J Austr. 2022, 33(1):57-67. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Xu R, Jiang Y, Zhang W. How Environmental Knowledge Management Promotes Employee Green Behavior: An Empirical Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 29;18(9):4738. [CrossRef]

- Sung QC, Lin ML, Shiao KY, Wei CC, Jan YL, Huang L.T. Changing behaviors: Does knowledge matter? A structural equation modeling study on green building literacy of undergraduates in Taiwan. Sustainable Environment Research, 2014, 24(3), 173–183.

- Truelove HB, Carrico AR, Weber EU, Raimi KT, Vandenbergh MP. Positive and negative spillover of pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and theoretical framework. Global Environmental Change, 2014, 29, 127–138. [CrossRef]

- Watson L, Hegtvedt K, Johnson C, Parris C, Subramanyam S. When legitimacy shapes environmentally responsible behaviors: Considering exposure to university sustainability initiatives. Education Sciences, 2017, 7(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Watson L, Johnson C, Hegtvedt K, Parris C. Living green: Examining sustainable dorms and identities. Int J Sustainability in Higher Edu, 2015, 16(3), 310–326. [CrossRef]

- Whitley CT, Takahashi B, Zwickle A, Besley JC, Lertpratchya AP. Sustainability behaviors among college students: An application of the VBN theory. Environmental Education Research, 2018, 24(2), 245–262. [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh L, O’Neill S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J Environ Psychol, 2010, 30(3), 305–314. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton EM. Green Building, Green Behavior? An Analysis of Building Characteristics that Support Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. Environment and Behavior, 2021, 53(4), 409–450. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Lu, Y.; Gou, Z. Green Building Pro-Environment Behaviors: Are Green Users Also Green Buyers? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1703. [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and research agenda. J Environ Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–95.

- Staddon, S.C.; Cycil, C.; Goulden, M.; Leygue, C.; Spence, A. Intervening to change behavior and save energy in the workplace: A systematic review of available evidence. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2016, 17, 30–51. [CrossRef]

- Spaveras, A.; Antoniadou, M. Awareness of Students and Dentists on Sustainability Issues, Safety of Use and Disposal of Dental Amalgam. Dent J. 2023, 11, 21. [CrossRef]

- Gou Z, Lau SSY, Prasad D. Market readiness and policy implications for green buildings: Case study from Hong Kong. J Green Build. 2013, 8, 162–173. [CrossRef]

- Ma C, Rogers AA, Krag, ME, Zhang F, Polyakov M, Gibson F, Chalak M, Pandit, R, Tapsuwan S. Consumers’ willingness to pay for renewable energy: A meta-regression analysis. Resour Energy Econ. 2015, 42, 93–109. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).