Submitted:

21 April 2023

Posted:

25 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

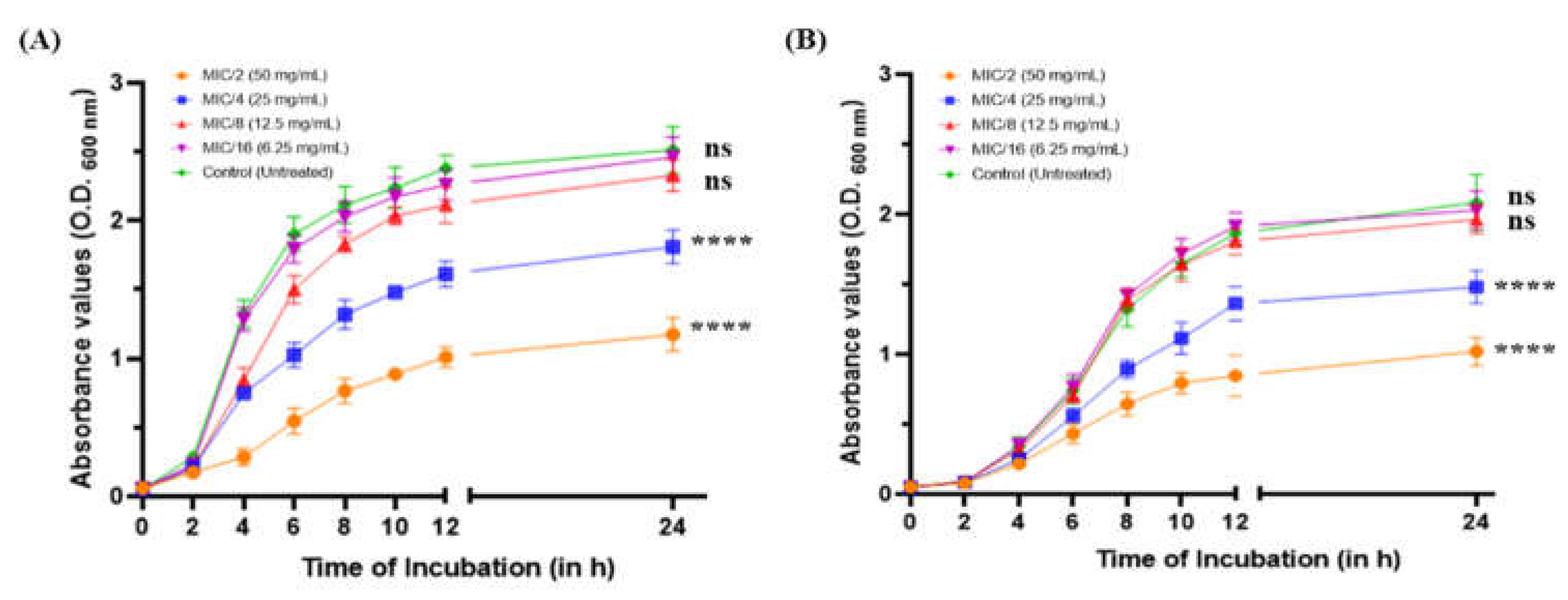

2.1. Effect of MeT on the Growth Profile of P. aeruginosa

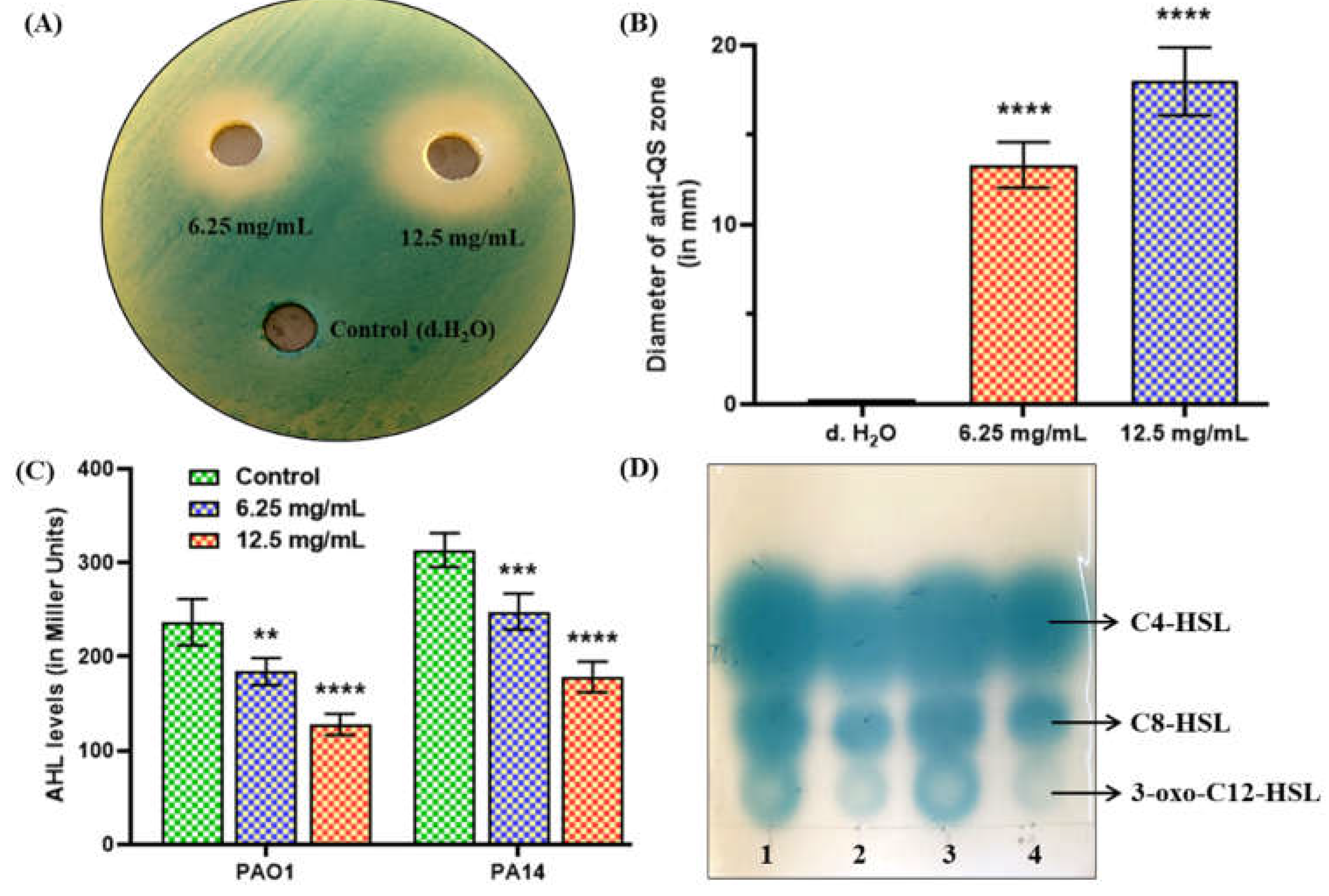

2.2. MeT Disrupts QS by Inhibiting AHL Production in P. aeruginosa

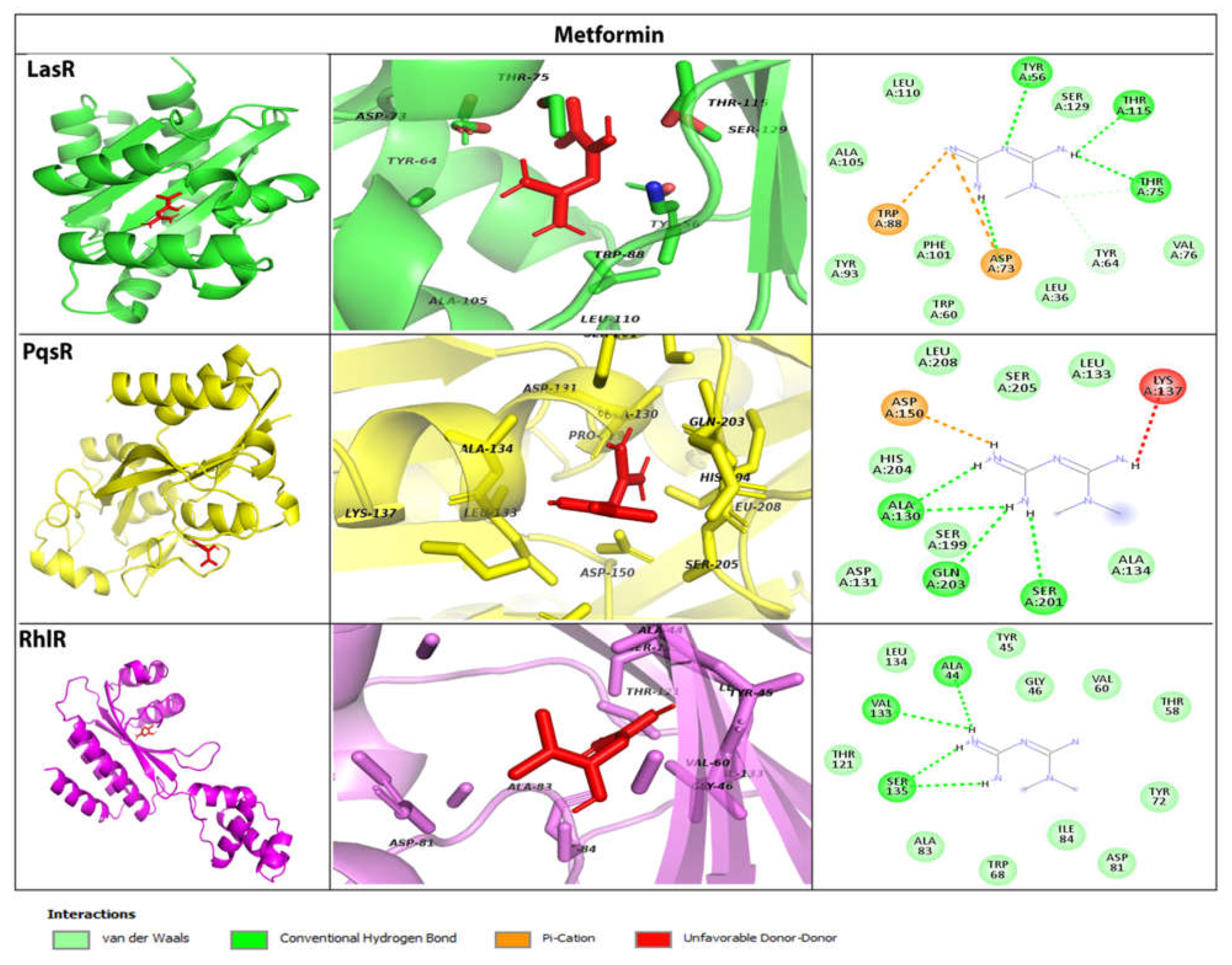

2.3. MeT Associates with QS Receptors & Possibly Inhibits Signal Transduction in P. aeruginosa

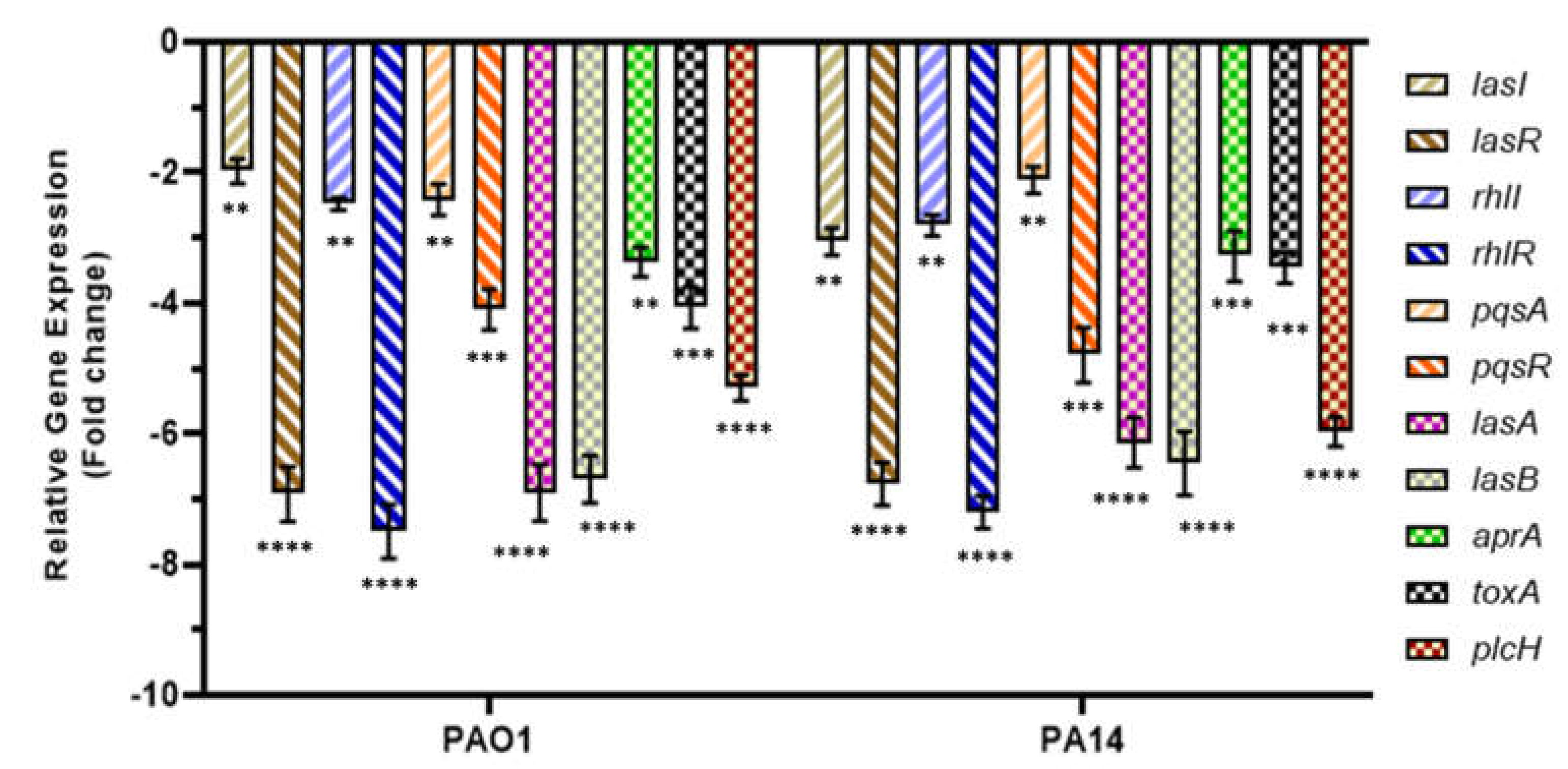

2.4. MeT Suppresses QS and QS-Associated Virulence Genes in P. aeruginosa

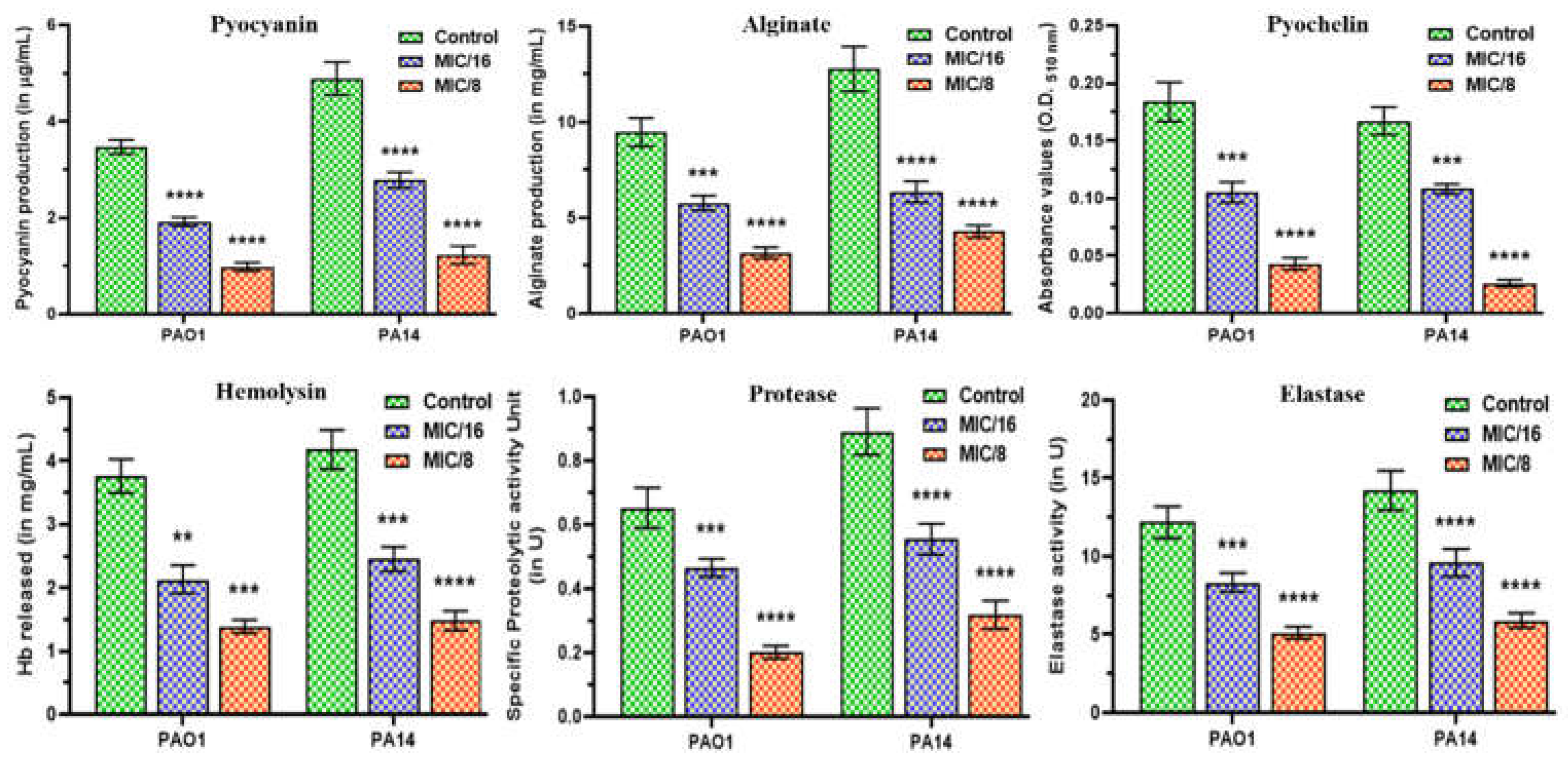

2.5. MeT Displays Anti-Virulence Properties by Phenotypically Inhibiting the Hallmark Virulence Factors in P. aeruginosa

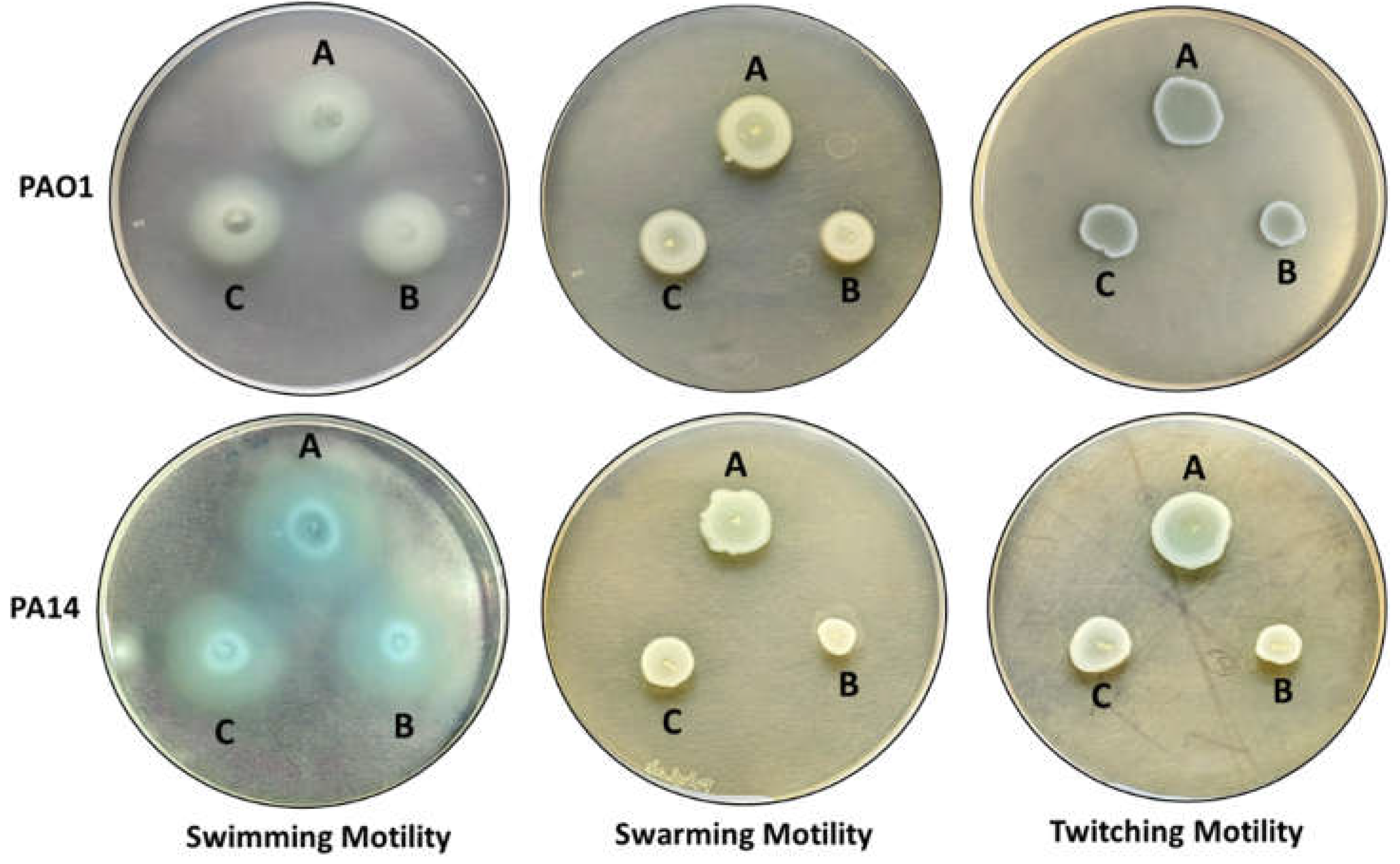

2.6. MeT Retards the Motility Phenotypes of P. aeruginosa

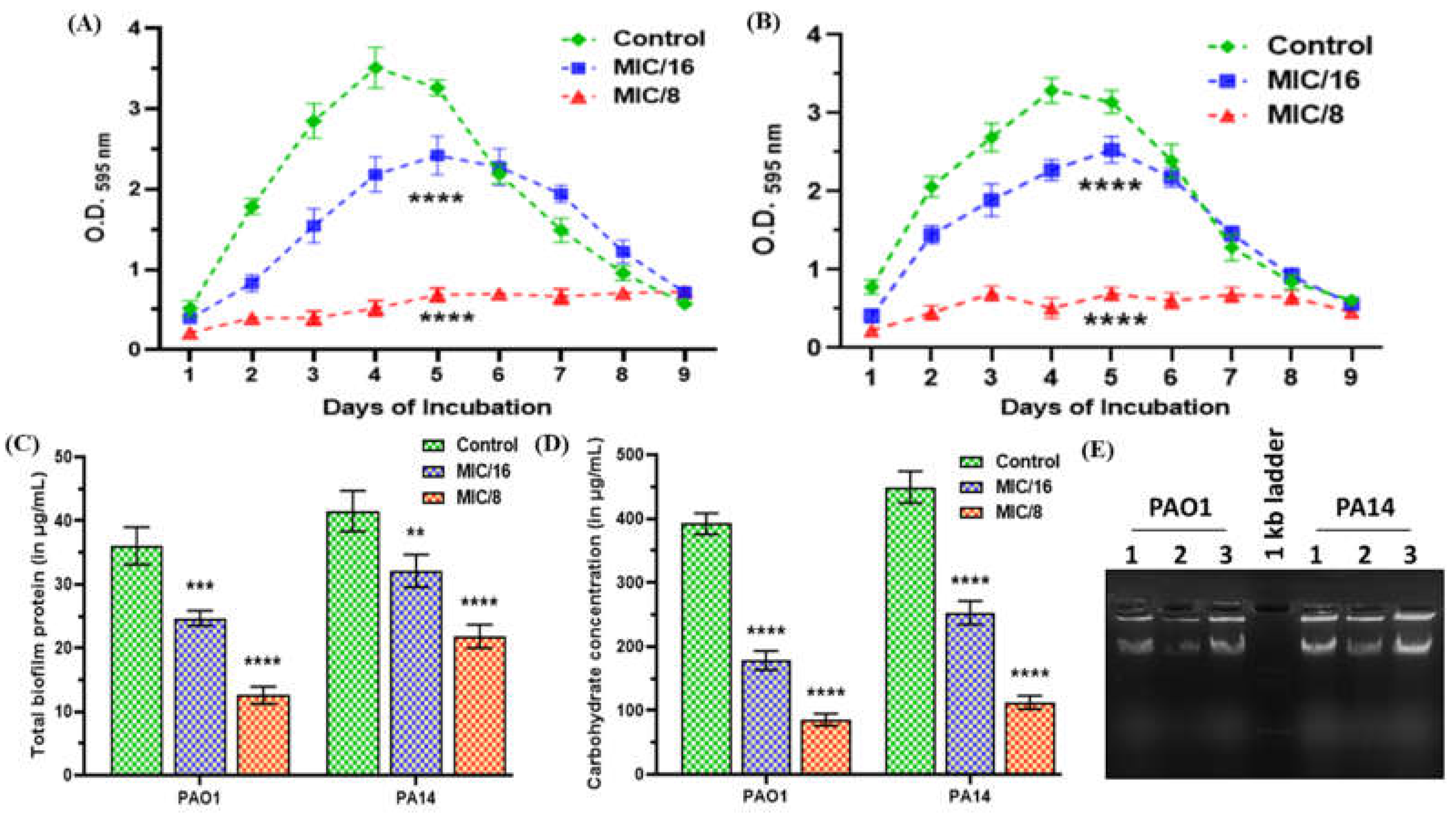

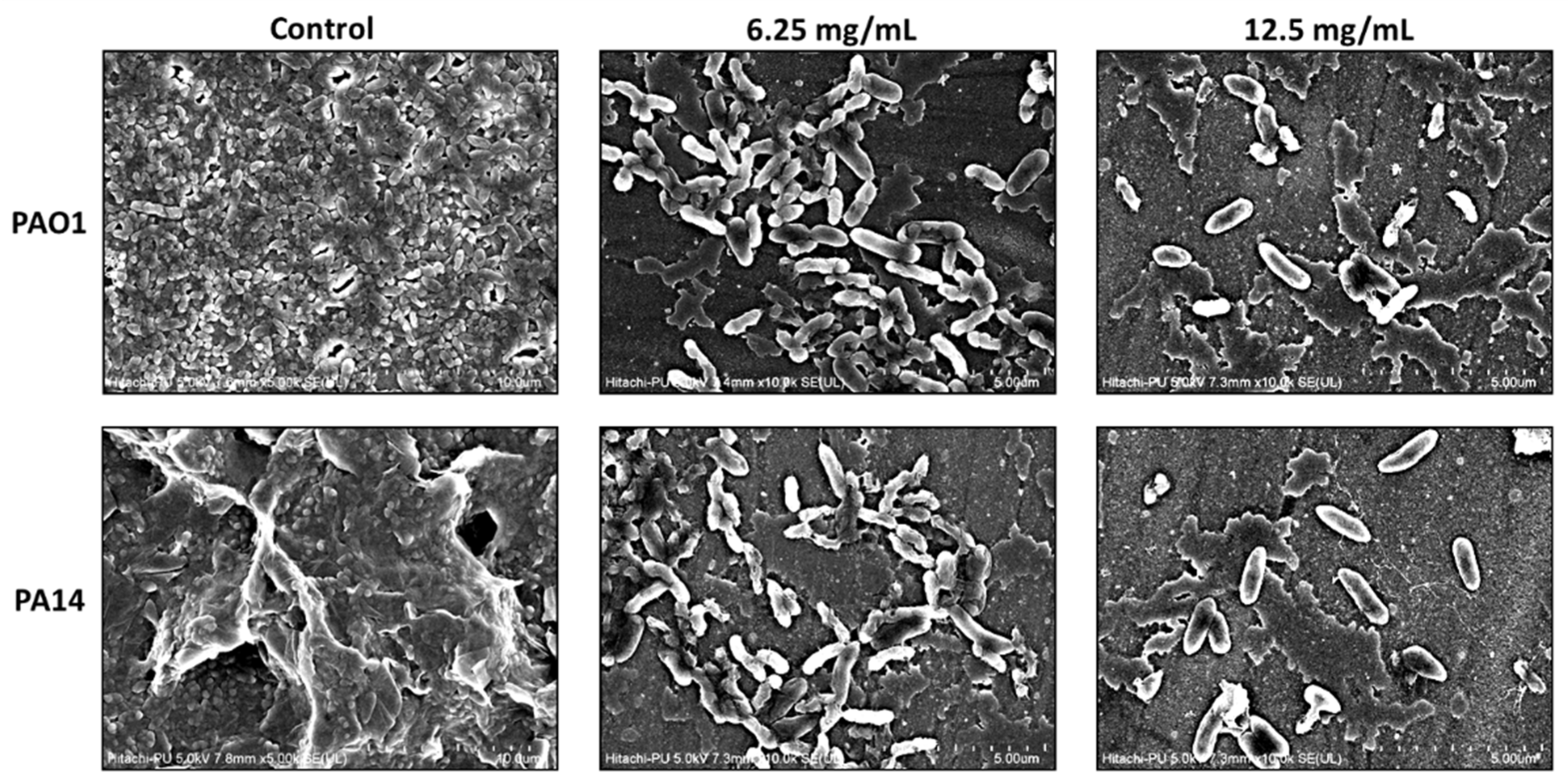

2.7. MeT Inhibits Biofilm Development by Abrogating EPS Production in P. aeruginosa

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strains, Culture Conditions, and Chemicals

3.2. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

3.3. Growth Analysis at Sub-MICs

3.4. AHL Extraction and Biosensor Assay for Determining the QQ Potential

3.5. Agar Overlay Method to Assess AHL Production

3.6. Quantitative Estimation of Total AHL Production Using β-Galactosidase Assay

3.7. Ligand Standardization and Molecular Docking Studies

3.8. RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR)

3.9. Effect on QS-Regulated Virulence Factors of P. aeruginosa

3.10. Effect on Motility Phenotypes of P. aeruginosa

3.11. Examining the Anti-Fouling Prospects of MeT

3.11.1. Quantitative Biofilm Inhibition Assay

3.11.2. Extraction & Estimation of Total Biofilm Protein

3.11.3. Extraction & Estimation of Total Biofilm Exopolysaccharides (EPS)

3.11.4. Isolation and Qualitative Estimation of Extracellular DNA (eDNA) from P. aeruginosa Biofilms

3.11.5. Microscopic Evaluation of P. aeruginosa Biofilms

3.12. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chadha, J. In vitro effects of sub-inhibitory concentrations of amoxicillin on physiological responses and virulence determinants in a commensal strain of Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 131, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadha, J.; Khullar, L. Subinhibitory concentrations of nalidixic acid alter bacterial physiology and induce anthropogenic resistance in a commensal strain of Escherichia coli in vitro. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 73, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadha, J.; Gupta, M.; Nagpal, N.; Sharma, M.; Adarsh, T.; Joshi, V.; Tiku, V.; Mittal, T.; Nain, V.K.; Singh, A.; et al. Antibacterial potential of indigenous plant extracts against multidrug-resistant bacterial strains isolated from New Delhi region. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 14, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; García-Contreras, R.; Pu, M.; Sheng, L.; Garcia, L.R.; Tomás, M.; Wood, T.K. Quorum quenching quandary: Resistance to antivirulence compounds. ISME J. 2011, 6, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadha, J.; Harjai, K.; Chhibber, S. Repurposing phytochemicals as anti-virulent agents to attenuate quorum sensing-regulated virulence factors and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 15, 1695–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, J.; Harjai, K.; Chhibber, S. Revisiting the virulence hallmarks of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A chronicle through the perspective of quorum sensing. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 24, 2630–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. WHO publishes list of bacteria for which new antibiotics are urgently needed. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Chadha, J.; Thakur, N.; Chhibber, S.; Harjai, K. A comprehensive status update on modification of foley catheter to combat catheter-associated urinary tract infections and microbial biofilms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Zhang, L. The hierarchy quorum sensing network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Cell 2014, 6, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, J.; Ravi; Singh, J. ; Harjai, K. α-Terpineol synergizes with gentamicin to rescue Caenorhabditis elegans from Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection by attenuating quorum sensing-regulated virulence. Life Sci. 2023, 313, 121267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, J.; Ravi; Singh, J. ; Chhibber, S.; Harjai, K. Gentamicin Augments the Quorum Quenching Potential of Cinnamaldehyde In Vitro and Protects Caenorhabditis elegans From Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Guo, Y. Metformin and Its Benefits for Various Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-W.; He, S.-J.; Feng, X.; Cheng, J.; Luo, Y.-T.; Tian, L.; Huang, Q. Metformin: A review of its potential indications. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2017, 11, 2421–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Jiang, X. Synergy of Non-antibiotic Drugs and Pyrimidinethiol on Gold Nanoparticles against Superbugs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12940–12943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masadeh, M.M.; Alzoubi, K.H.; Masadeh, M.M.; Aburashed, Z.O. Metformin as a Potential Adjuvant Antimicrobial Agent Against Multidrug Resistant Bacteria. Clin. Pharmacol. Adv. Appl. 2021, 13, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nievas, F.; Bogino, P.; Sorroche, F.; Giordano, W. Detection, Characterization, and Biological Effect of Quorum-Sensing Signaling Molecules in Peanut-Nodulating Bradyrhizobia. Sensors 2012, 12, 2851–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M.; Liu, L.; Wu, R.; Hu, J.; Wang, S.; Li, P. Detection of New Quorum Sensing N-Acyl Homoserine Lactones From Aeromonas veronii. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjai, K.; Gupta, P.; Chhibber, S. Subinhibitory concentration of ciprofloxacin targets quorum sensing system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing inhibition of biofilm formation & reduction of virulence. Indian J. Med. Res. 2016, 143, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Hao, S.; Zhao, L.; Shi, F.; Ye, G.; Zou, Y.; Song, X.; Li, L.; Yin, Z.; He, X.; et al. Paeonol Attenuates Quorum-Sensing Regulated Virulence and Biofilm Formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Brenner, N.; Brice, J.; Klein-Seetharaman, J.; Sarkar, S.K. Cephalosporins Interfere With Quorum Sensing and Improve the Ability of Caenorhabditis elegans to Survive Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Chhibber, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, M.; Harjai, K. Zingerone silences quorum sensing and attenuates virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Fitoterapia 2015, 102, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mowafy, S.A.; Shaaban, M.I.; Abd El Galil, K.H. Sodium ascorbate as a quorum sensing inhibitor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, L.; Wu, T.-Q.; Xiong, Y.-S.; Ni, H.-B.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, W.-C.; Chu, S.-P.; Ju, S.-Q.; Yu, J. Ibuprofen-mediated potential inhibition of biofilm development and quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Life Sci. 2019, 237, 116947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajire, S.K.; Jain, S.; Johnson, R.P.; Shastry, R.P. 6-Methylcoumarin attenuates quorum sensing and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and its applications on solid surface coatings with polyurethane. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 8647–8661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seleem, N.M.; Atallah, H.; Abd El Latif, H.K.; Shaldam, M.A.; El-Ganiny, A.M. Could the analgesic drugs, paracetamol and indomethacin, function as quorum sensing inhibitors? Microb. Pathog. 2021, 158, 105097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shastry, R.P.; Ghate, S.D.; Sukesh Kumar, B.; Srinath, B.S.; Kumar, V. Vanillin derivative inhibits quorum sensing and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A study in a Caenorhabditis elegans infection model. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 36, 1610–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Park, J.-S.; Choi, H.-Y.; Yoon, S.S.; Kim, W.-G. Terrein is an inhibitor of quorum sensing and c-di-GMP in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A connection between quorum sensing and c-di-GMP. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, T.S.; Ledizet, M.; Kazmierczak, B.I. Swarming motility, secretion of type 3 effectors and biofilm formation phenotypes exhibited within a large cohort of Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 59, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, R.; Vanderleyden, J.; Michiels, J. Quorum sensing and swarming migration in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 28, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Cámara, M. Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009, 12, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradali, M.F.; Ghods, S.; Rehm, B.H.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lifestyle: A Paradigm for Adaptation, Survival, and Persistence. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiegand, I.; Hilpert, K.; Hancock, R.E.W. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.C.; Sandhu, P.; Gupta, P.; Rudrapaul, P.; De, U.C.; Tribedi, P.; Akhter, Y.; Bhattacharjee, S. Attenuation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation by Vitexin: A combinatorial study with azithromycin and gentamicin. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.K.; Nirbhavane, P.; Batra, M.; Chhibber, S.; Harjai, K. Nanolipoidal α-terpineol modulates quorum sensing regulated virulence and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 1743–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshynets, O.V.; Baranovskyi, T.P.; Iungin, O.S.; Kysil, N.P.; Metelytsia, L.O.; Pokholenko, I.; Potochilova, V.V.; Potters, G.; Rudnieva, K.L.; Rymar, S.Y.; et al. eDNA Inactivation and Biofilm Inhibition by the PolymericBiocide Polyhexamethylene Guanidine Hydrochloride (PHMG-Cl). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| QS Receptors | Ligands | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Interacting Amino Acid Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| LasR | 3-oxo-C12-HSL | -8.2 | Leu36, Gly38, Leu40, Tyr47, Ala50, Ile52, Tyr56, Trp60, Arg61, Tyr64, Ala70, Asp73, Thr75, Val76, Trp88, Tyr93, Phe101, Ala105, Leu110, Leu125, Gly126, Ala127, Ser129 |

| MeT | -6.4 | Leu36, Tyr56, Trp60, Tyr64, Asp73, Thr75, Val76, Trp88, Tyr93, Phe101, Ala105, Leu110, Thr115, Ser129 | |

| Furanone C-30 | -6.6 | Leu36, Tyr47, Ala50, Ile52, Tyr56, Trp60, Arg61, Tyr64, Thr75, Val76, Ala127, Ser129 | |

| RhlR | C4-HSL | -7.4 | Ala44, Gly46, Trp68, Tyr72, Asp81, Ala83, Ile84, Trp96, Phe101, Leu107, Thr121, Val133, Ser135 |

| MeT | -6.0 | Ala44, Tyr45, Gly46, Thr58, Val60, Trp68, Tyr72, Asp81, Ala83, Ile84, Thr121, Val133, Leu134, Ser135 | |

| Furanone C-30 | -5.9 | Ala44, Val60, Trp68, Tyr72, Asp81, Ala83, Trp96, Leu107, Val133, Ser135 | |

| PqsR | PQS | -6.7 | Ile149, Gln194, Ser196, Leu197, Leu207, Leu208, Arg209, Pro210, Val211, Phe221, Met224, Ile236, Ile263, Thr265 |

| MeT | -5.8 | His204, Ala130, Asp131, Leu133, Ala134, Lys137, Asp150, Ser199, Ser201, Gln203, Ser205, Leu208 | |

| Furanone C-30 | -5.7 | Ala102, Ser128, Pro129, Ala130, Ile149, Gln194, Leu197, Leu208, Phe221, Ala237, Ile236, Pro238 |

| Motility Phenotype | Diameter of Bacterial Growth (in mm) ± Standard Deviation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAO1 | PA14 | |||||

| Control | 1/8 MIC | 1/16 MIC | Control | 1/8 MIC | 1/16 MIC | |

| Swimming | 42.34 ± 3.0767 | 30.67 ± 2.804 | 35.167 ± 2.639 | 35.83 ± 0.983 | 27.34 ± 1.032 | 30.34 ± 1.861 |

| Swarming | 18.167 ± 0.408 | 12.5 ± 0.547 | 14.5 ± 0.547 | 17.0 ± 0.894 | 9.34 ± 1.211 | 12.67 ± 0.816 |

| Twitching | 19.834 ± 1.169 | 16.34 ± 0.816 | 17.5 ± 0.836 | 18.34 ± 0.816 | 10.41 ± 0.491 | 13.167 ± 0.752 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).