1. Introduction

Shrimp is one of the most important aquatic animals in aquaculture. However, frequent diseases caused by bacteria, viruses and parasites always lead to sever economic losses, which greatly hinder the healthy development of shrimp aquaculture. Acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND), previously called early mortality syndrome (EMS), is one of the most serious diseases caused by bacteria [

1]. The agents causing AHPND are

Vibrio species that contain a plasmid encoding the lethal toxins PirA and PirB [

2].

Vibrio parahaemolyticus (

VpAHPND) carrying the plasmid is one of the causative agents leading to AHPND in shrimp aquaculture [

3].

Although hepatopancreas is the main target tissue of the bacteria,

V. parahaemolyticus tends to cause systemic responses in the host. In the stomach of

Penaeus monodon, many immune related genes including antimicrobial peptides, proPO system, proteinase/proteinase inhibitors, and signal transduction pathways were responsive to

V. parahaemolyticus infection [

4]. In the hemocytes of

L. vannamei, genes related to carbohydrate metabolism, lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and cell growth and anti-apoptosis were significantly changed after

V. parahaemolyticus infection [

5]. Another study target to the hemocytes of

L. vannamei identified many immune related genes such as crustin, anti-lipopolysaccharide factor, serpin 3, C-type lectin responsive to

V. parahaemolyticus infection [

6]. In the hepatopancreas of

Litopenaeus vannamei, genes related to programmed cell death, carbohydrate metabolism, and biological adhesion were up-regulated after

V. parahaemolyticus infection [

7]. Another study revealed that the hepatopancreas of

L. vannamei responded to

V. parahaemolyticus by activating glucose metabolism, energy metabolism, amino acid metabolism, nucleic acid synthesis, as well as HIF-1 signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and NF-KappaB signaling pathway [

8]. These data provide useful information for our understanding of the overall responses of the host against

V. parahaemolyticus infection.

Due to the different genetic backgrounds, shrimp exhibit distinct disease-resistant abilities to

V. parahaemolyticus. The variation of disease-resistant ability could be reflected by differential expression of genes at the background level. In

P. vannamei, several genes including chymotrypsin A, serine protease, crustin-P and prophenol oxidase activation system 2 showed differential expression levels between

VpAHPND tolerant and susceptible populations [

9]. A transcriptomic comparison between three

VpAHPND resistant and three susceptible families identified 489 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in

L. vannamei and 19 tested genes also showed different expression in their offspring [

10]. Although few common genes were reported in different studies due to the distinct genetic background, these identified genes could be used as potential biomarkers for understanding

VpAHPND resistant of shrimp. However, there is still lack of effective strategies to find out key genes and regulatory processes that used for host defense again

VpAHPND infection.

As the main immune related tissue, hemocytes play important roles in host defense against pathogen infection. However, the identification of genes in hemocytes related to VpAHPND resistance has not been reported. In the present study, the comparative transcriptome analysis was performed on two independent populations. The transcriptional expression profiles were analyzed at the background level of hemocytes from shrimp with different resistant abilities against VpAHPND infection in each population. Some genes related to VpAHPND resistance were identified in shrimp hemocytes while no common DEG existed between two comparisons. A strategy was proposed based on the present study for further identification of key genes and regulatory processes related to disease resistance.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental animals

Two batches of Litopenaeus vannamei purchased from Rizhao breeding farm in Shandong were used for two independent experiments. Before experiments, the shrimp were cultured in aerated seawater laboratory aquaculture tank at 26 ℃ for seven days. The shrimp weights were 10 g ± 0.5 g in the first batch (population 1) and 19.5 g ± 1 g in the second batch (population 2).

2.2. Visible Implant Elastomer (VIE) fluorescent labeling and hemolymph collection

The VIE distinguished with eight different colors (red, pink, orange, brown, white, purple, green, yellow) was injected into each shrimp in the third segment with different color fluorescence. After one week, 200 μl hemolymph was exsanguinated from each shrimp with a sterile syringe containing an equal volume of ice-cold anticoagulant (27 mM trisodium citrate, 336 mM sodium chloride, 115 mM glucose, 9mM EDTA•Na2⋅2H2O, pH 7.4). The hemocytes were separated by centrifugation at 1000 g for 10 min and stored in −80 °C. Then, all the shrimp were returned to the laboratory tanks.

2.3. V. parahaemolyticus immersion and hepatopancreas collection

One week after exsanguination, the shrimp were infected with V. parahaemolyticus. The bacteria strain was cultured in tryptic soy broth with 2% sodium chloride liquid media. The cultured bacteria were further checked by positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of PirAvp and PirBvp genes. Bacterial titer was counted with a hemocytometer under a light microscope. The soak infection dose in two batches of shrimp were set at the medial lethal doses, 2.5x106 CFU/ml and 5x106 CFU/ml respectively. The mortality was continuously recorded for two days. The hepatopancreas of moribund shrimp and survival shrimp after infection for 48 h were collected and stored at −80 °C.

2.4. DNA extraction and bacteria load detection

The DNA from the hepatopancreas was extracted using TIANGEN Plant Genomic DNA Extraction Kit according to the manufacture’s instruction. The concentration and purity of DNA were determined using NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) by coagulation and 1% gel electrophoresis. PirA copy number was estimated by Ependorf MasterCycler EP Realplex (Ependorff, Germany) using TaqMan Assay. A forward primer 5′-GGTGACCAGACCTGCTTTGAG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CCAGCTAGGATAACCGTAACATG-3′ were used to amplify a 284 bp fragment of PirA gene, with a TaqMan hydrolysis probe 5′-FAM-CCGCCAGCCATAAATGGCGCACC-BHQ1-3′). The amplification program consisted of one cycle of contamination digestion at 37 °C for 2 min, one cycle of pre- denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, and 45 cycle of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s and extension at 60 °C for 30 s. A standard curve was obtained using serial dilutions of plasmid PirA (full-length ORF of PirA gene of V. parahaemolyticus was cloned into pUC57 vector), which was used to quantify the V. parahaemolyticus copy number. Each assay was carried out in four parallel. Therefore, all shrimp were divided into resistant group and sensitive group (9hpi, 12hpi and the surviving individual) according to the time of death and vibrio load.

2.5. RNA extraction and transcriptome sequencing

Based on the death and survival data and Vibrio load data, all shrimp were divided into V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible individuals. The collected hemocytes of V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp were mixed respectively. For population 1, three biological replicates were prepared for resistant and susceptible shrimp. The samples were designated as HcS1-1, HcS1-2 and HcS1-3 for resistant shrimp and designated as HcD1-1, HcD1-2 and HcD1-3 for susceptible shrimp. For population 2, four replicates were prepared for resistant and susceptible shrimp. The samples were designated as HcS2-1, HcS2-2, HcS2-3 and HcS2-4 for resistant shrimp and designated as HcD2-1, HcD2-2, HcD2-3 and HcD2-4 for susceptible shrimp. Total RNA of hemocytes was then extracted by RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa, Kyoto, Japan) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. The total RNA was qualified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified by NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Fragmentation buffer was used to break the mRNA into short fragments. The first cDNA strand was synthesized using random hexamers, followed by the addition of buffer, dNTPs, RNase H, and DNA polymerase I to synthesize the second cDNA strand. Poly(A) was added to connect to the sequencing adaptor. Finally, the Illumina HiSeqTM platform was used to sequence the library at Guangzhou Sagene Biotech Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China).

2.6. De novo Assembly and Annotations

In order to ensure the data quality, the clean reads obtained from the preliminary filtering were subjected to more stringent filtering. High-quality clean reads were obtained by eliminating all the reads containing the A base and more than 10% of the reads containing N. The clean reads were mapped to the reference genome of

L. vannamei by HISAT2.2.4 [

11]. The mapped reads were assembled using StringTie v 1.3.1 [

12] in a reference-based approach. The reconstructed transcripts were aligned to the reference genome. Annotation was carried out by blast against Nr (NCBI non-redundant proteins), KEGG (genomic encyclopedia database), COG (homologous protein cluster), and Swiss-Prot databases.

2.7. Differential Expression and Enrichment Analysis

The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in hemocytes between

V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible were identified by calculating the FPKM (fragment per kliobase of transcript per million mapped reads) value. DEGs were analyzed using the edgeR package (

http://www.rproject.org/), with the parameter of false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and the absolute fold change ≥ 2. The correlation analysis between samples was carried out among samples to ensure the reliability of experimental data.

The Gene Ontology (GO) function and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses of DEGs were performed using the online OmicShare tools (

http://www. omicshare.com/tools). The Q value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. The loads of V. parahaemolyticus in hepatopancreas of infected shrimp

In order to distinguish the resistant ability of shrimp against

V. parahaemolyticus infection, the load of

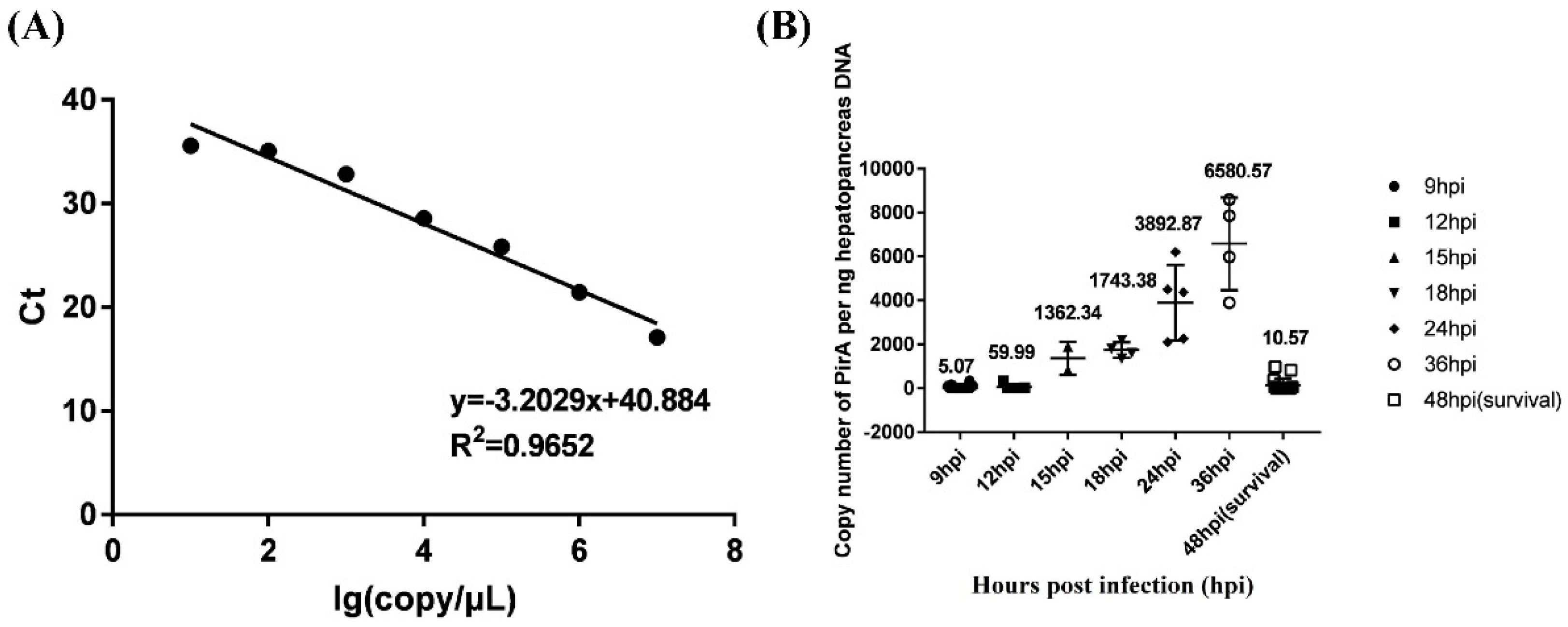

V. parahaemolyticus in hepatopancreas of infected shrimp was detected. A standard curve equation of PirA

Vp was established as y=-3.2029x+40.884, where x represented the log value of

Vibrio copy number per μL standard plasmid PirA and y represented the Ct value. The correlation coefficient was 0.9652, which showed a good linear relationship between the concentration of standard substance and the Ct value obtained (

Figure 1A).

The Ct value of each shrimp detected by Taqman fluorescence quantitative PCR was substituted into the standard curve of PirA to calculate the number of

Vibrio copies per ng DNA. As shown in

Figure 1B, the loads of

V. parahaemolyticus in hepatopancreas of shrimp died at 9 hpi and 12 hpi were very low, which were 5.07 and 59.99 copies per ng hepatopancreas DNA. The loads of

V. parahaemolyticus were high in hepatopancreas of shrimp died at 15 hpi, 18 hpi, 24 hpi and 36 hpi, all of which were more than 1000 copies per ng hepatopancreas DNA. The load of

V. parahaemolyticus in hepatopancreas of survival shrimp (still alive at 48 hpi) was 10.57 copies per ng hepatopancreas DNA. According to the death time and the load of

V. parahaemolyticus in hepatopancreas, shrimp that died at 9 hpi and 12 hpi were deemed as susceptible individuals and those survival after 48 hpi were deemed as resistant individuals. Hemocytes from

V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in two populations were used for independent comparative transcriptome analysis.

Figure 1.

The load of V. parahaemolyticus in hepatopancreas of infected shrimp from two populations. (A) showed the standard curve equation of PirAVp. (B) showed the copy number of V. parahaemolyticus per ng hepatopancreas DNA at different hours post infection (hpi). Survival shrimp after 48 hpi was expressed by 48hpi(survival).

Figure 1.

The load of V. parahaemolyticus in hepatopancreas of infected shrimp from two populations. (A) showed the standard curve equation of PirAVp. (B) showed the copy number of V. parahaemolyticus per ng hepatopancreas DNA at different hours post infection (hpi). Survival shrimp after 48 hpi was expressed by 48hpi(survival).

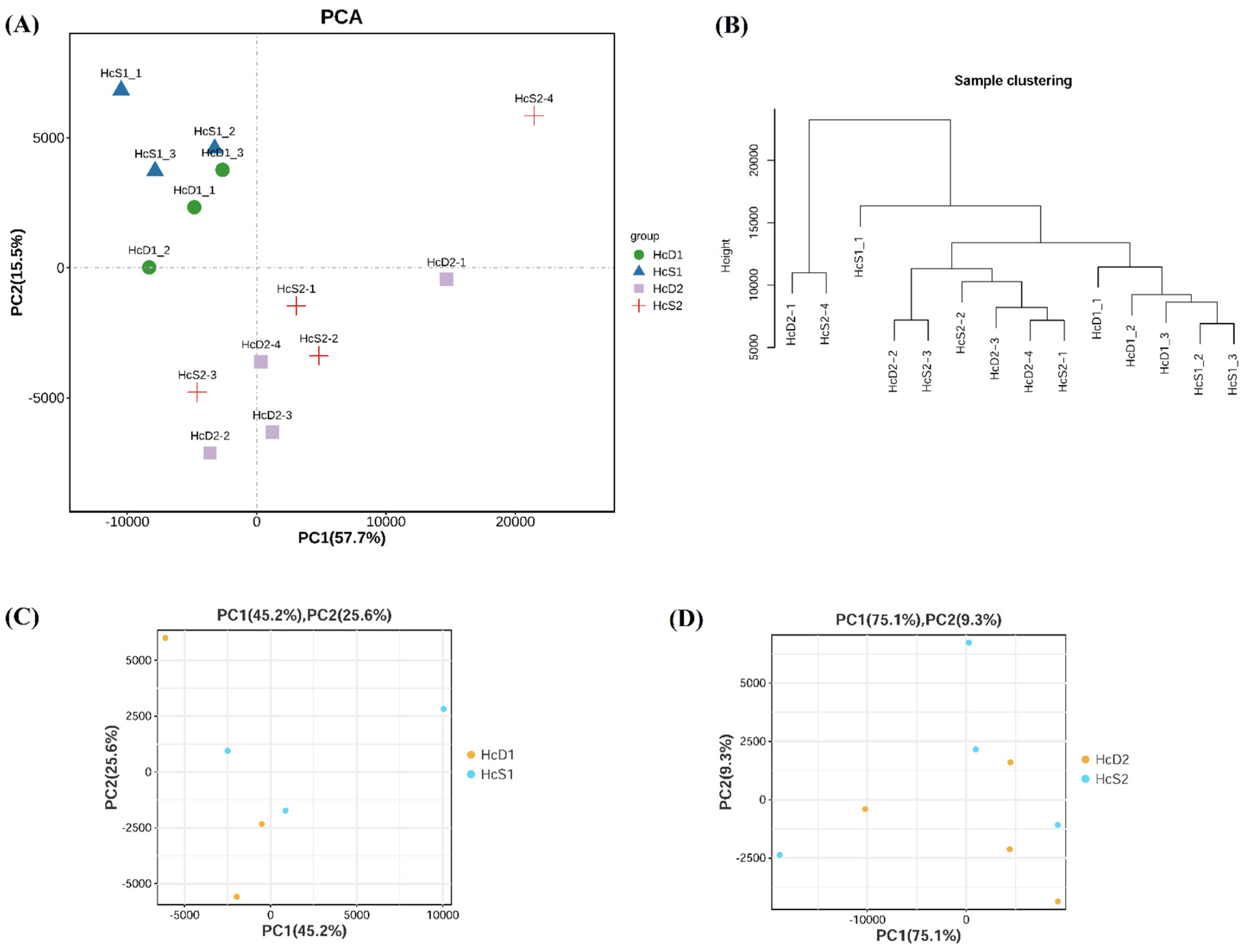

3.2. The correlation of the transcriptome data from all samples

The relationship of all samples from two populations were analyzed by PCA and sample clustering methods. The results showed that samples from the same population had a close relationship (

Figure 2A and 2B). However, the difference between

V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp was small in each population (

Figure 2C and 2D). The results suggest that shrimp from the same population, even with different

V. parahaemolyticus resistant abilities, has more similar transcriptome profiles than those from different populations.

Figure 2.

Sample relationship analyzed by principal component analysis (PCA) and sample clustering. (A) and (B) showed the results of PCA and clustering analysis for all samples from two populations. (C) and (D) showed the results of PCA for samples from population 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 2.

Sample relationship analyzed by principal component analysis (PCA) and sample clustering. (A) and (B) showed the results of PCA and clustering analysis for all samples from two populations. (C) and (D) showed the results of PCA for samples from population 1 and 2, respectively.

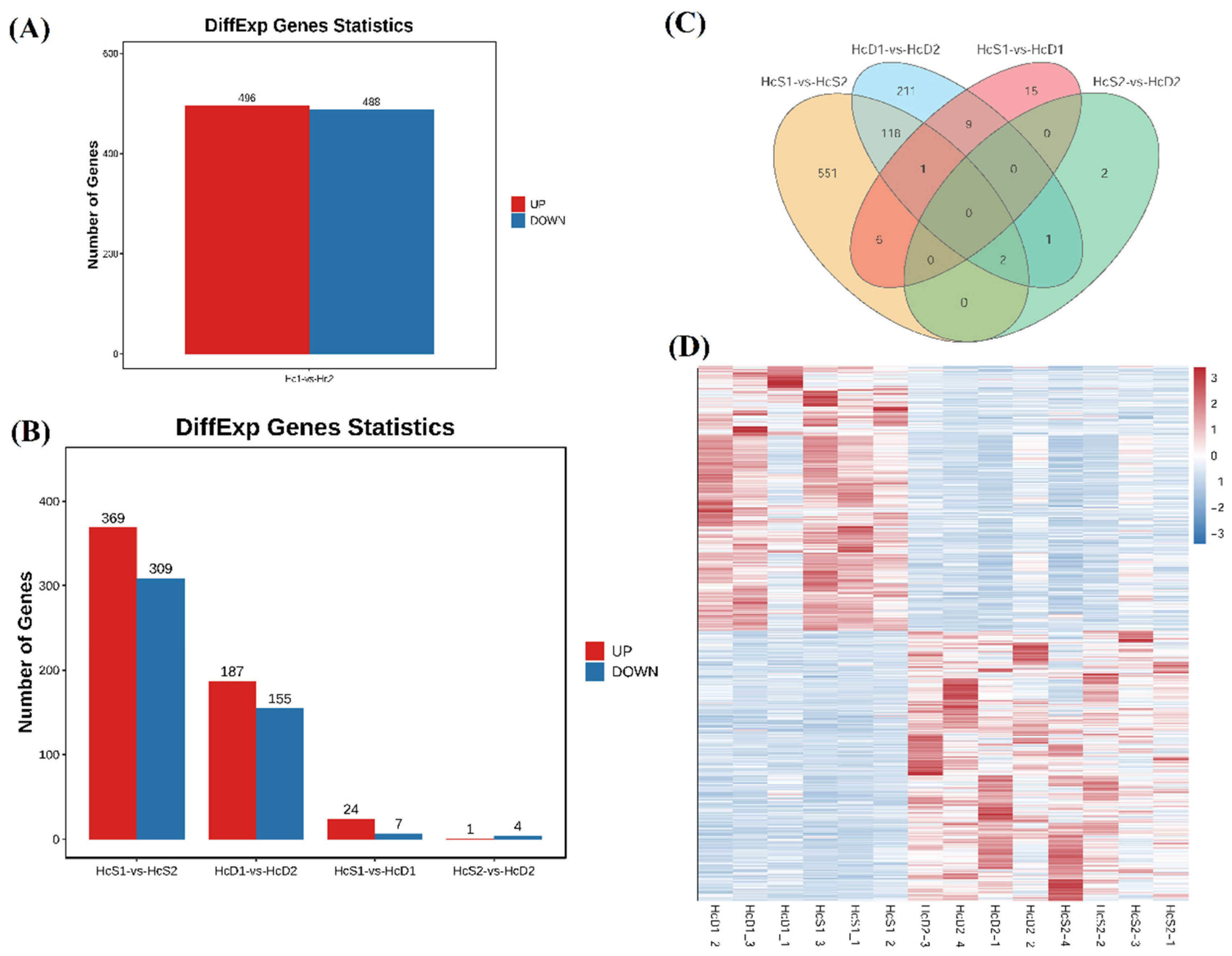

3.3. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between two populations and between V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp

Corresponding to the sample relationship, much more DEGs were identified between two populations than those between

V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in each population. Between two populations, there were a total of 984 DEGs, including 496 up-regulated DEGs and 488 down-regulated DEGs in the hemocytes from population 2 (

Figure 3A). There were 678 DEGs between the

V. parahaemolyticus resistant shrimp between population 1 and 2 (

Figure 3B, HcS1-vs-HcS2). There were 342 DEGs the

V. parahaemolyticus susceptible shrimp between population 1 and 2 (

Figure 3B, HcD1-vs-HcD2).

Very few DEGs were identified between

V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp. There were 31 DEGs and 5 DEGs between

V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in population 1 and population 2, respectively (

Figure 3B, HcS1-vs-HcD1, HcS2-vs-HcD2).

A total of 121 DEGs were overlapping between HcS1-vs-HcS2 and HcD1-vs-HcD2 (

Figure 3C). The expression trends of these DEGs showed distinct differences between two populations (

Figure 3D). However, there was no overlapping DEGs between HcS1-vs-HcD1 and HcS2-vs-HcD2 (

Figure 3C), indicating that the disease resistant mechanism of shrimp against

V. parahaemolyticus infection was different in two populations.

Figure 3.

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between different comparisons. (A) showed DEGs between population 1 and 2. (B) showed DEGs from comparisons HcS1-vs-HcS2, HcD1-vs-HcD2, HcS1-vs-HcD1 and HcS2-vs-HcD2. (C) showed the result of Venn analysis of DEGs from different comparisons. (D) showed the heatmap of DEGs between two populations.

Figure 3.

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between different comparisons. (A) showed DEGs between population 1 and 2. (B) showed DEGs from comparisons HcS1-vs-HcS2, HcD1-vs-HcD2, HcS1-vs-HcD1 and HcS2-vs-HcD2. (C) showed the result of Venn analysis of DEGs from different comparisons. (D) showed the heatmap of DEGs between two populations.

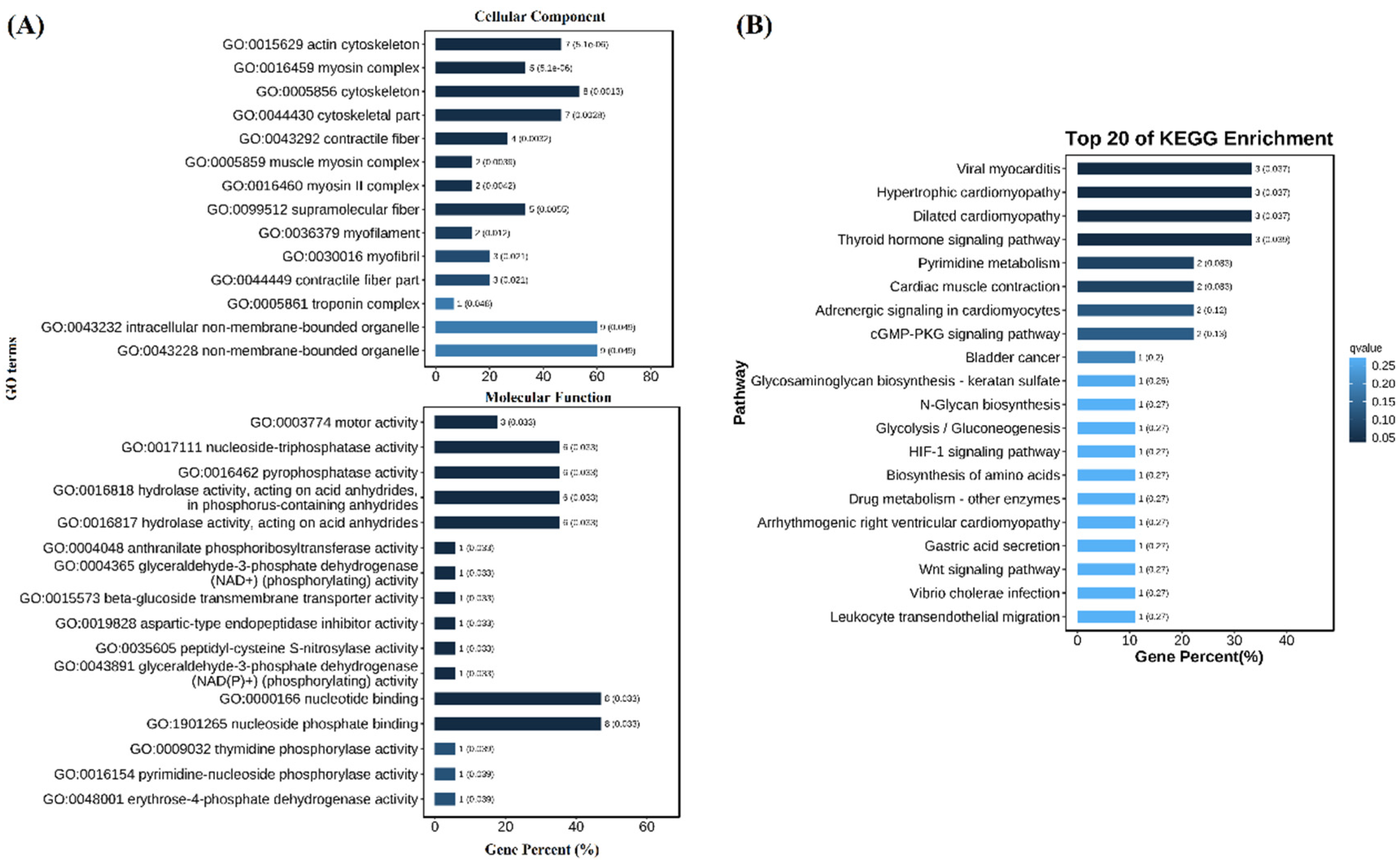

3.4. Enriched GO items and KEGG pathways between V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp

GO and KEGG enrichment results showed many DEGs in population 1 were enriched in GO items and KEGG pathways. The enrichment items in cell composition were mainly “actin cytoskeleton”, “myosin complex”, “cytoskeleton”, etc. The enriched items in molecular function were “motor activity”, “nucleoside-triphosphatase activity”, “pyrophosphatase activity”, etc. (

Figure 4A). The enriched KEGG pathways included “viral myocarditis”, “hypertrophic cardiomyopathy”, “dilated cardiomyopathy” and “thyroid hormone signaling pathway” (

Figure 4B). There was no GO item and KEGG pathway enriched for DEGs in population 2 because only five DEGs were identified.

Figure 4.

GO (A) and KEGG (B) enrichment of DEGs between V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in population 1.

Figure 4.

GO (A) and KEGG (B) enrichment of DEGs between V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in population 1.

3.5. Detailed analysis of DEGs between V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp

Among the 31 DEGs in population 1, 19 had functional annotations (

Table 1). Most of these DEGs exhibited higher expression levels in

V. parahaemolyticus susceptible shrimp. DEGs encoded cytoskeleton related proteins, including troponin, myosin, septin-4, and actin, as well as immune and signal transduction-related genes, such as immune-associated nucleotide-binding protein 13-like, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase TRIM32, and MAM and LDL-receptor class A domain-containing protein 2-like, had higher expression levels in

V. parahaemolyticus susceptible shrimp. Sugar metabolism related genes including glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase and alpha-(1,6)-fucosyltransferase-like were also highly expressed in

V. parahaemolyticus susceptible shrimp.

Table 1.

DEGs with functional annotations between V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in population 1.

Table 1.

DEGs with functional annotations between V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in population 1.

| Gene ID |

HcS1_fpkm |

HcD1_fpkm |

log2(HcD1/HcS1) |

FDR |

Description |

| ncbi_113820920 |

0.40 |

0.00 |

-8.63 |

0.0376 |

structural maintenance of chromosomes protein 2-like |

| ncbi_113815624 |

0.71 |

0.08 |

-3.13 |

0.0154 |

vang-like protein 2 |

| MSTRG.1662 |

5.77 |

1.38 |

-2.07 |

0.0017 |

APC membrane recruitment protein 1-like |

| ncbi_113812130 |

67.07 |

109.46 |

0.71 |

0.0499 |

4-coumarate--CoA ligase 1 isoform X1 |

| ncbi_113824615 |

186.25 |

373.56 |

1.00 |

0.0001 |

spermatogonial stem-cell renewal factor |

| MSTRG.4583 |

11.36 |

42.55 |

1.91 |

0.0154 |

arasin-like protein |

| ncbi_113807541 |

51.35 |

197.85 |

1.95 |

0.0397 |

immune-associated nucleotide-binding protein 13-like |

| ncbi_113817613 |

5.39 |

25.35 |

2.23 |

0.0027 |

E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase TRIM32 |

| ncbi_113824399 |

82.06 |

388.92 |

2.24 |

0.0023 |

Septin-4-like protein |

| ncbi_113813611 |

0.34 |

3.21 |

3.24 |

0.0373 |

troponin I |

| ncbi_113805465 |

0.66 |

6.27 |

3.25 |

0.0017 |

myosin light chain 2 |

| ncbi_113822686 |

0.65 |

7.58 |

3.55 |

0.0001 |

myosin light chain |

| ncbi_113820123 |

5.27 |

68.89 |

3.71 |

0.0000 |

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase |

| ncbi_113819252 |

0.12 |

2.74 |

4.50 |

0.0154 |

actin 2 |

| ncbi_113816511 |

0.04 |

0.95 |

4.64 |

0.0035 |

myosin heavy chain, muscle-like isoform X4 |

| MSTRG.15220 |

0.18 |

7.35 |

5.34 |

0.0002 |

Retrovirus-related Pol polyprotein from transposon 297 |

| ncbi_113807016 |

0.01 |

0.43 |

6.44 |

0.0411 |

myosin heavy chain, muscle-like isoform X8 |

| ncbi_113823028 |

0.00 |

2.97 |

11.53 |

0.0000 |

alpha-(1,6)-fucosyltransferase-like |

| ncbi_113829244 |

0.00 |

10.32 |

13.33 |

0.0000 |

MAM and LDL-receptor class A domain-containing protein 2-like |

In population 2, one cytoskeleton related genes encoding tubulin α-3 was also highly expressed in

V. parahaemolyticus susceptible shrimp. The other four DEGs, including dihydropyrimidinase-like isoform X3, prohibitin, iroquois-class homeodomain protein IRX-2-like, and diacylglycerol kinase 1, were all highly expressed in

V. parahaemolyticus resistant shrimp (

Table 2).

Table 2.

DEGs with functional annotations between V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in population 2.

Table 2.

DEGs with functional annotations between V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in population 2.

| Gene ID |

HcS2_fpkm |

HcD2_fpkm |

log2(HcD2/HcS2) |

FDR |

Description |

| ncbi_113815990 |

11.16 |

3.46 |

-1.69 |

0.0184 |

dihydropyrimidinase-like isoform X3 |

| ncbi_113825784 |

13.80 |

5.06 |

-1.45 |

0.0473 |

prohibitin |

| ncbi_113824882 |

5.22 |

2.06 |

-1.34 |

0.0184 |

iroquois-class homeodomain protein IRX-2-like |

| ncbi_113829145 |

6.34 |

2.66 |

-1.25 |

0.0402 |

diacylglycerol kinase 1 |

| ncbi_113813376 |

1.43 |

6.81 |

2.26 |

0.0142 |

tubulin alpha-3 chain-like |

4. Discussion

In order to screen genes in shrimp hemocytes related to V. parahaemolyticus resistance, the present study established a method to collect hemocytes from shrimp with different resistant abilities against V. parahaemolyticus infection. The results showed that shrimp more susceptible to V. parahaemolyticus infection died early with low pathogen load. When shrimp exhibited higher resistant ability against V. parahaemolyticus infection, they could suffer from higher pathogen load and stayed alive for longer time. Shrimp with the highest resistant ability against V. parahaemolyticus infection could clear the pathogen in hepatopancreas after a longer time (48 h) post infection. Some other studies constructed families with distinct resistances against specific pathogen, while individuals in the same family usually exhibited different disease resistant abilities. The method used in the present study could collect hemocytes from shrimp before pathogen infection with clear pathogen resistant information.

Two independent transcriptome analyses on hemocytes of shrimp with different

V. parahaemolyticus resistant abilities were carried out, which aimed to identify common genes related to the biological trait. However, the identified DEGs in two populations shared no overlap. Some transcriptome studies also identified genes related to

V. parahaemolyticus resistance in shrimp hepatopancreas, but the identified genes were rarely overlap [

9,

10]. The results were comparable with the data from the present study. It might be caused by the different genetic backgrounds of shrimp used in different studies. In other words, different populations might employ distinct molecular mechanisms to resist

V. parahaemolyticus infection. This brings difficulties for identification of key genes or regulatory processes related to specific pathogen.

Although there was no overlap between DEGs identified from two populations, many DEGs were reported relevant to immunity or pathogen infection. The cytoskeleton has four main components including actin, microtubules, intermediate filaments and septins, which all have important functions in cell-autonomous immunity [

13]. An E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase TRIM32 gene was crucial under oxidase stress and during

Vibrio infection in

L. vannamei [

14]. In intestine, the MAM and LDL-receptor class A domain-containing protein could regulate enterohepatic bile acid signaling, while bile acids are vital factors in mucosal immunity and inflammation [

15,

16]. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase is the key enzyme in the glycolytic pathway, which benefits viral replication during white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) in shrimp [

17]. These genes were differentially expressed in hemocytes between

V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible shrimp in population 1, indicating that these genes might contribute to the resistant ability of shrimp against

V. parahaemolyticus infection.

Although the DEGs in population 2 were totally different with those in population 1, they were also related to immunity and pathogen infection. In the central nervous system, dihydropyrimidinase-like 3 could regulate the inflammatory response of activated immune cells microglia, which respond to infection and inflammation by producing cytokines and phagocytosing cell debris and pathogens [

18]. In

Fenneropenaeus chinensis, two prohibitin genes played important roles in hemocytes during WSSV infection [

19]. Diacylglycerol kinase 1 is responsible for the ATP-dependent phosphorylation of diacylglycerol to phosphatidic acid, both of which are crucial second messengers involved in many immune processes such as regulating Toll-like receptor-induced cytokine production [

20]. Tubulin alpha-3 is the major constituent of microtubules, one component of cytoskeleton. These genes might be responsible for variable resistant abilities of shrimp against

V. parahaemolyticus infection in population 2.

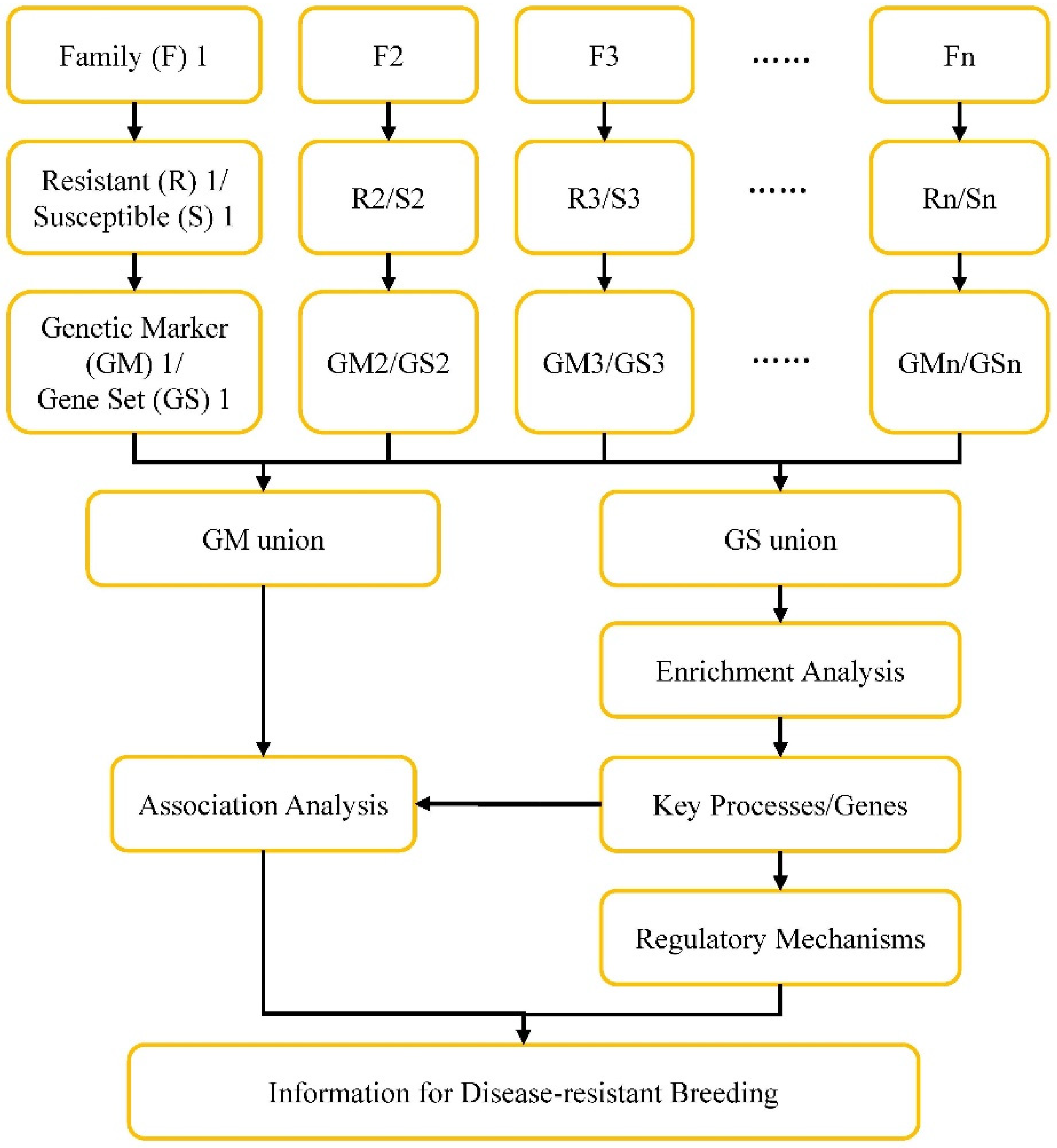

Although no common gene related to

V. parahaemolyticus resistance were identified in hemocytes from two populations, genes in specific GO item like cytoskeleton could be found in DEGs from both transcriptome data. It means that the key processes or genes related to

V. parahaemolyticus resistance could be obtained by comprehensive analysis of multiple omics data information. A strategy was proposed here to approach this purpose (

Figure 5). Individuals from the same family, which have relatively consistent genetic background, will be used to construct

V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible hemocytes samples based on the method established in the present study. Differentially expressed genes (Gene Set, GS) as well as genetic makers (GM) will be identified after comparative analysis between

V. parahaemolyticus resistant and susceptible samples from each family. The GS and GM information from each family will be pooled to obtain the GS union and GM union. The GS union will be put for GO and KEGG enrichment analysis to identify key processes and genes related to

V. parahaemolyticus resistance. Further association analysis between these identified key processes and genes and GM union will help to obtain useful genetic markers. The information will provide basis for understanding regulatory mechanisms of shrimp defense

V. parahaemolyticus infection and for disease-resistant breeding.

Figure 5.

Framework for identification of disease-resistant processes/genes and disease-resistance breeding of shrimp.

Figure 5.

Framework for identification of disease-resistant processes/genes and disease-resistance breeding of shrimp.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. and F.L; methodology, K.Z. and W.D.; statistical analysis, S.L. and K.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. and K.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (31830100), the General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (31972829), the earmarked fund for CARS-48 and the Taishan Scholars Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study used shrimp as experimental animals, which are not endangered invertebrates. In addition, there is no genetically modified organism used in the study. According to the national regulation (Fisheries Law of the People s Republic of China), no permission is required to collect the animals and no formal ethics approval is required for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the research team for their preparation of the materials for RNA-seq and technical support. Thanks for the data service provided by the Oceanographic Data Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CASODC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zorriehzahra, M.J., Banaederakhshan, R., Early Mortality Syndrome (EMS) as new Emerging Threat in Shrimp Industry. Adv Anim Vet Sci, 2015. 3: 64–72.

- Xiao, J., Liu, L., Ke, Y., et al., Shrimp AHPND-causing plasmids encoding the PirAB toxins as mediated by pirAB-Tn903 are prevalent in various Vibrio species. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: 42177. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.T., Chen, I.T., Lee, C.T., et al., Draft genome sequences of four strains of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, three of which cause early mortality syndrome/acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease in shrimp in China and Thailand, Genome Announc, 2014. 2(5): e00816–14. [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Lizárraga, A.E., Juárez-Morales, J.L., Racotta, I.S., et al., Transcriptomic analysis of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei, Boone 1931) in response to acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease caused by Vibrio parahaemolyticus. PLoS ONE, 2019. 14(8): e0220993. [CrossRef]

- Soonthornchai, W., Chaiyapechara, S., Klinbunga, S., et al., Differentially expressed transcripts in stomach of Penaeus monodon in response to AHPND infection analyzed by ion torrent sequencing. Dev Comp Immunol, 2016. 65: 53–63.

- Miao, M., Li, S., Liu, Y., et al., Transcriptome Analysis on Hepatopancreas Reveals the Metabolic Dysregulation Caused by Vibrio parahaemolyticus Infection in Litopenaeus vannamei. Biology, 2023. 12: 417. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z., Wang, F., Aweya, J.J., et al., Comparative transcriptomic analysis of shrimp hemocytes in response to acute hepatopancreas necrosis disease (AHPND) causing Vibrio parahemolyticus infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol, 2018. 74:10-18. [CrossRef]

- Maralit, B.A., Jaree, P., Boonchuen, P., et al., Differentially expressed genes in hemocytes of Litopenaeus vannamei challenged with Vibrio parahaemolyticus AHPND (VPAHPND) and VPAHPND toxin. Fish Shellfish Immunol, 2018. 81:284-296. [CrossRef]

- Mai, H.N., Caro, L.F.A., Cruz-Flores, R., et al., Differentially Expressed Genes in Hepatopancreas of Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease Tolerant and Susceptible Shrimp (Penaeus vannamei). Front Immunol, 2021. 12: 634152. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Yu, Y., Luo, Z., et al., Comparison of Gene Expression Between Resistant and Susceptible Families Against VPAHPND and Identification of Biomarkers Used for Resistance Evaluation in Litopenaeus vannamei. Front Genet, 2021. 12: 772442. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., Langmead, B., Salzberg, S.L., HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods, 2015. 12(4): 357-60. [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M., et al., StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol, 2015. 33(3): 290-5. [CrossRef]

- Mostowy, S., Shenoy, A. The cytoskeleton in cell-autonomous immunity: structural determinants of host defence. Nat Rev Immunol, 2015. 15: 559–573. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Lu, K.C., Chen, G.L., et al., A Litopenaeus vannamei TRIM32 gene is involved in oxidative stress response and innate immunity. Fish Shellfish Immunol, 2020. 107: 547-555. [CrossRef]

- Reue, K., Lee, J.M., Vergnes, L.. Regulation of bile acid homeostasis by the intestinal Diet1-FGF15/19 axis. Curr Opin Lipidol, 2014. 25(2): 140-7.

- Chen, M.L., Takeda, K., Sundrud, M.S., Emerging roles of bile acids in mucosal immunity and inflammation. Mucosal Immunol, 2019. 12(4): 851-861. [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.S., Lee, D.Y., Liu, C.H., et al., White Spot Syndrome Virus Triggers a Glycolytic Pathway in Shrimp Immune Cells (Hemocytes) to Benefit Its Replication. Front Immunol, 2022. 13: 901111. [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, J., Tay, S.S., Ling, E.A., et al., Dihydropyrimidinase-like 3 regulates the inflammatory response of activated microglia. Neuroscience, 2013. 253: 40-54. [CrossRef]

- Cui, C., Zhu, L., Tang, X., et al., Molecular characterization of prohibitins and their differential responses to WSSV infection in hemocyte subpopulations of Fenneropenaeus chinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol, 2020. 106: 296-306. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Shen, Y., Chen, Y. et al., Structure of membrane diacylglycerol kinase in lipid bilayers. Commun Biol, 2021. 4: 282. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).