Submitted:

20 April 2023

Posted:

21 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Subject Information

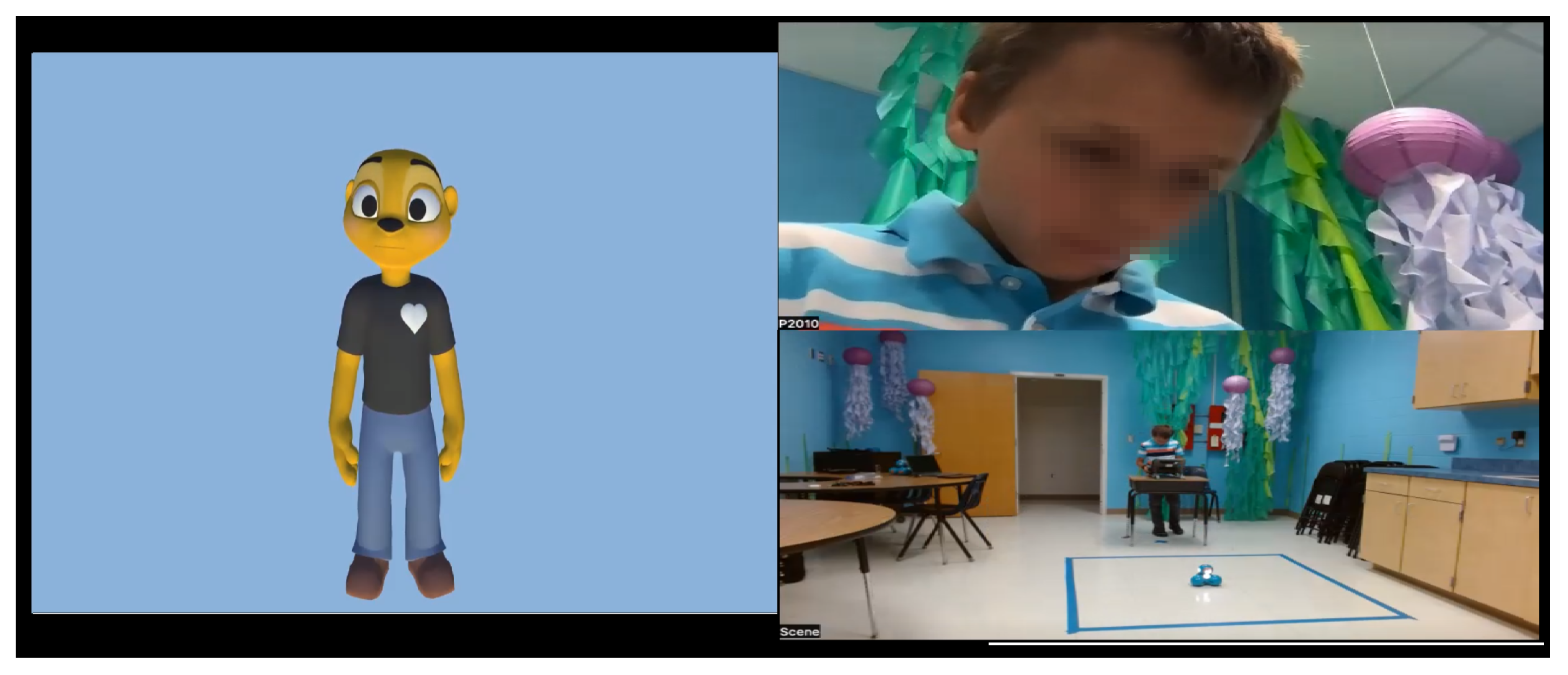

2.2. Interaction of Children with Avatar

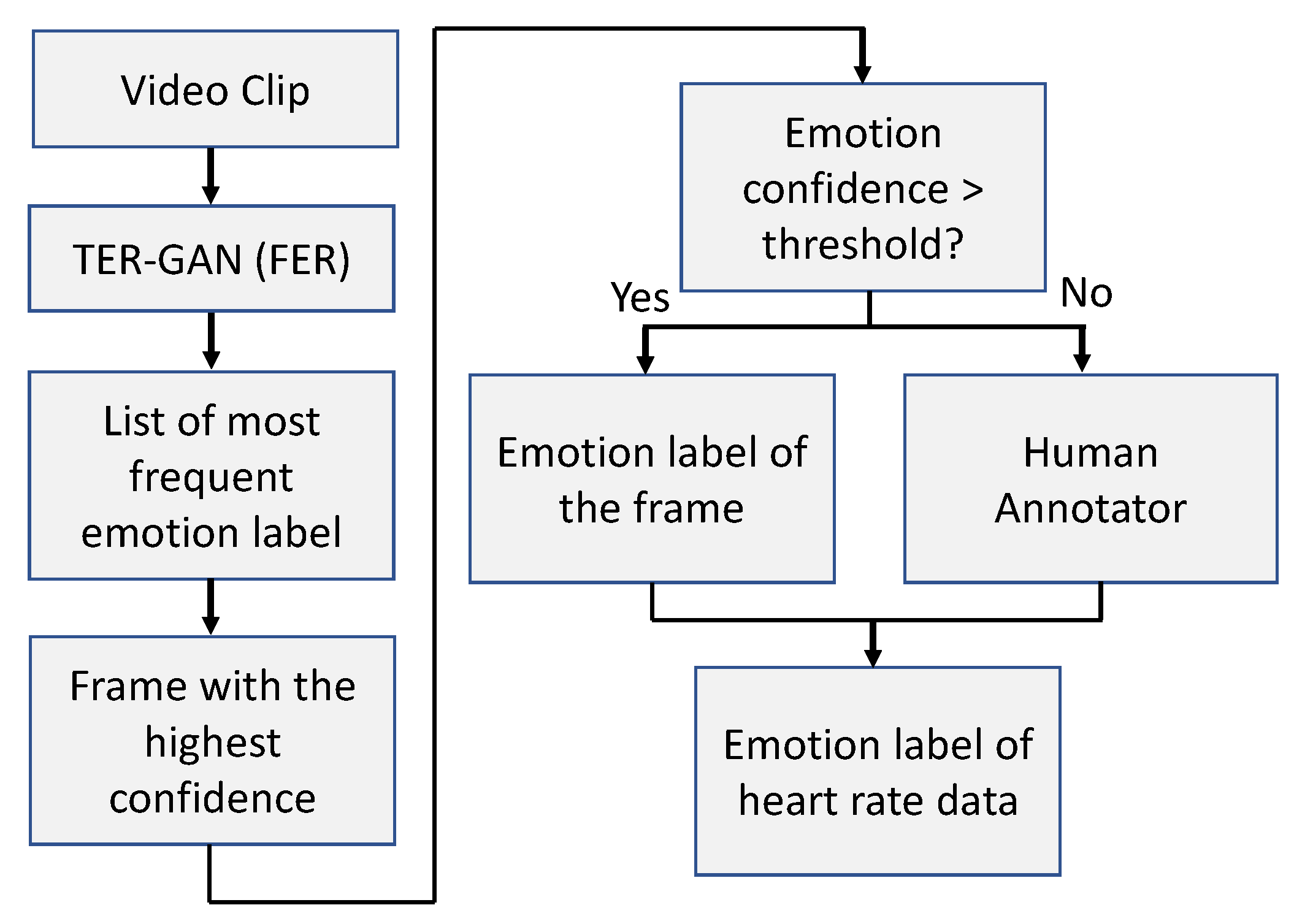

3. Semi-Automated Emotion Annotation Process

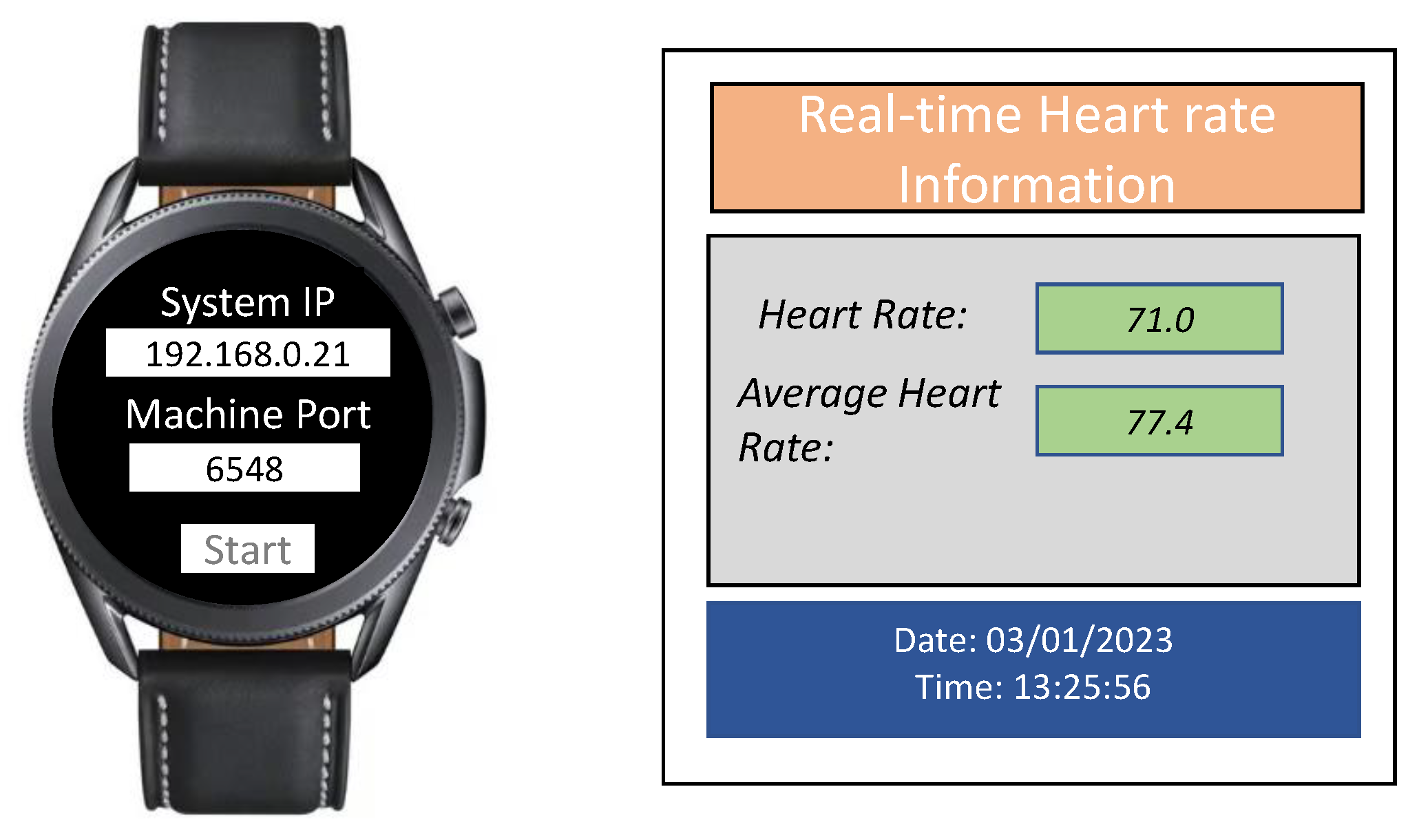

4. Feature Extraction

- represents heart rate at time t.

- n corresponds to the length of the time window.

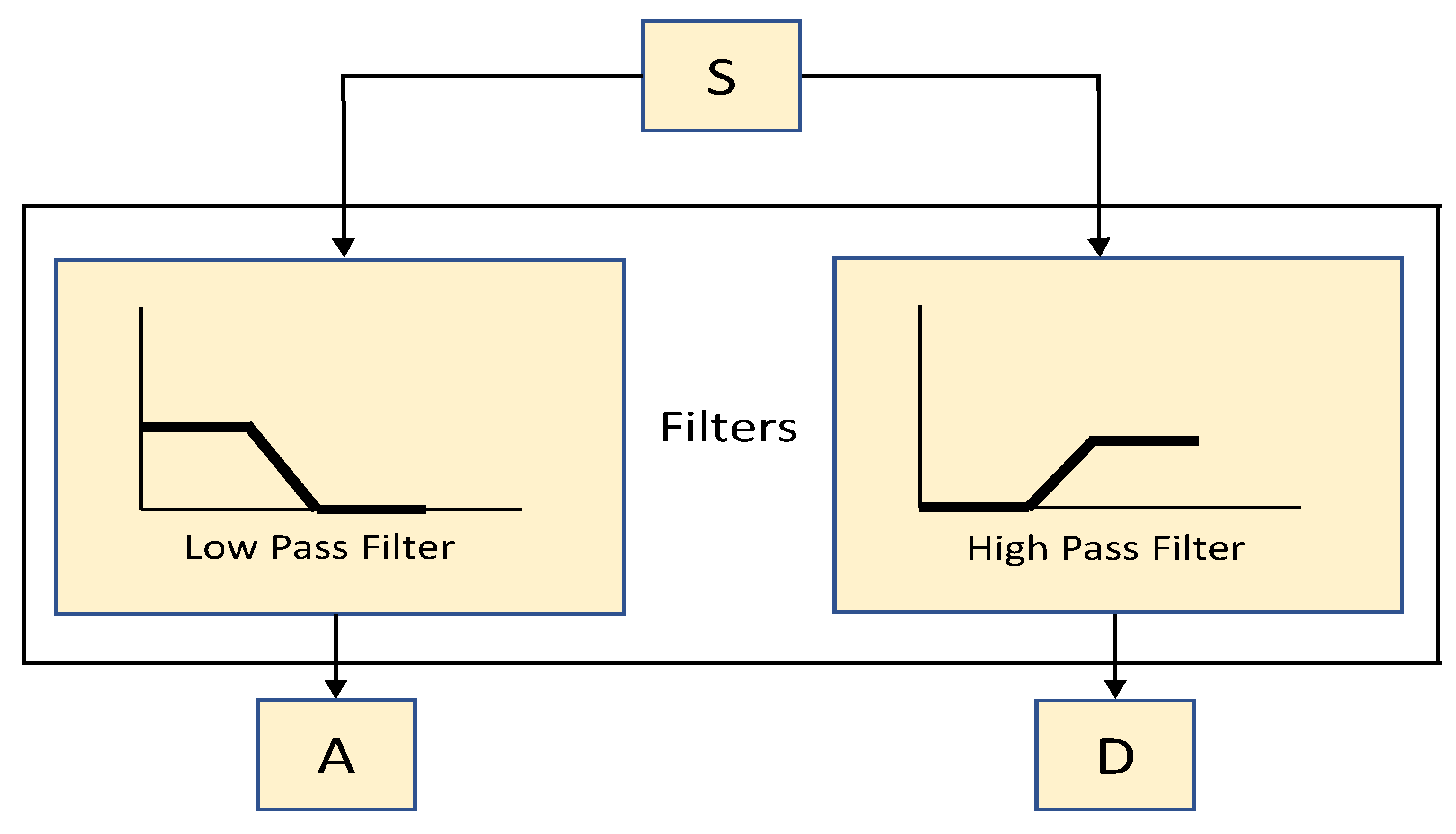

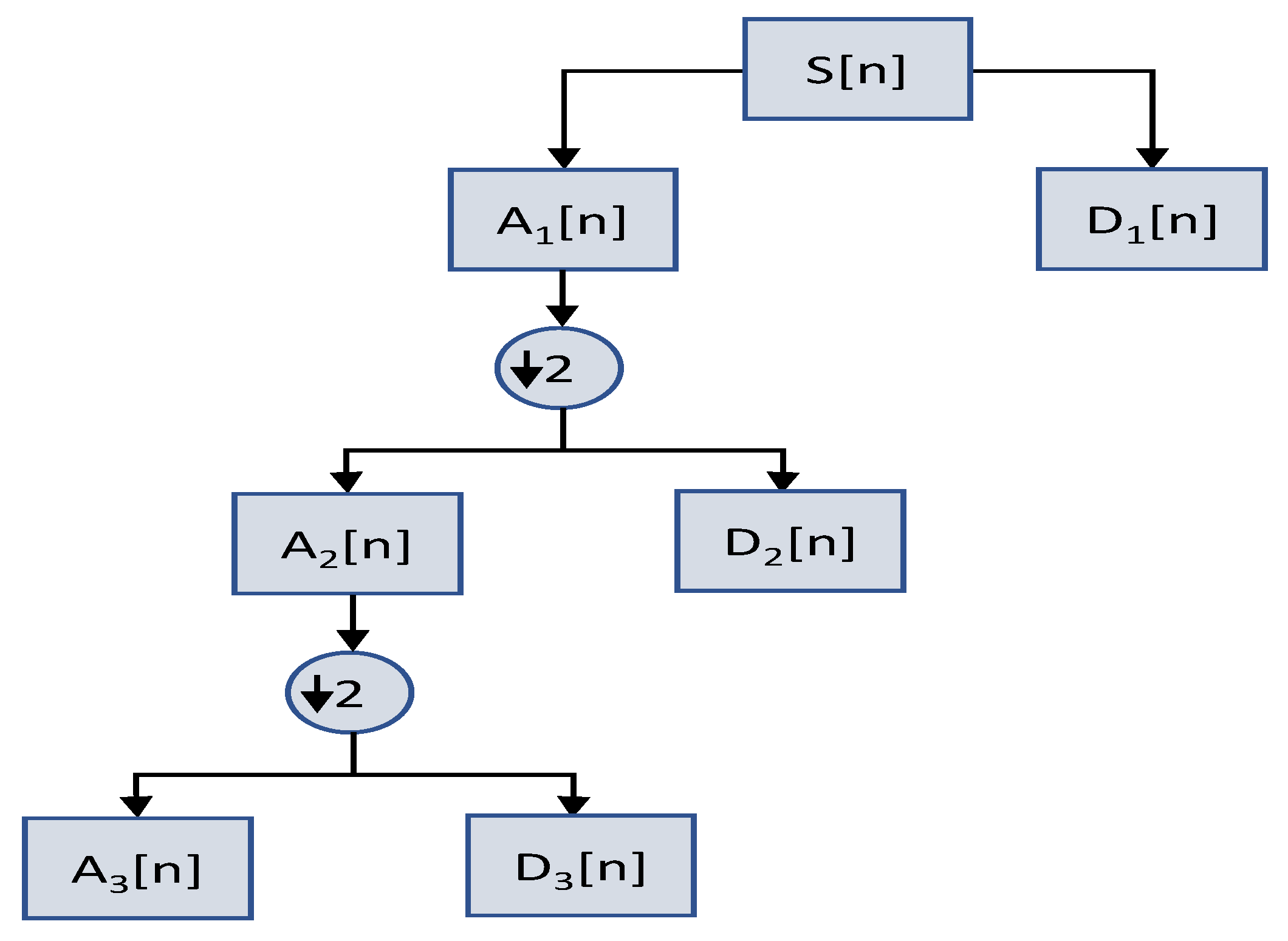

4.1. Discrete Wavelet Transform

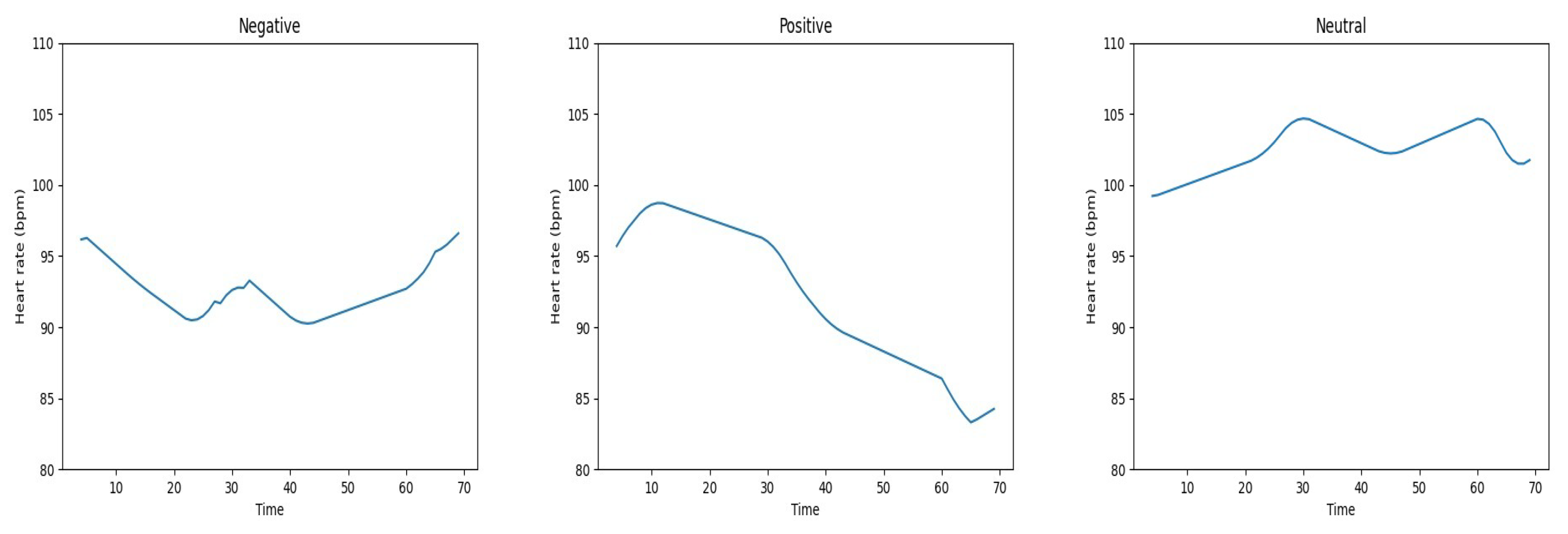

5. Emotion Recognition

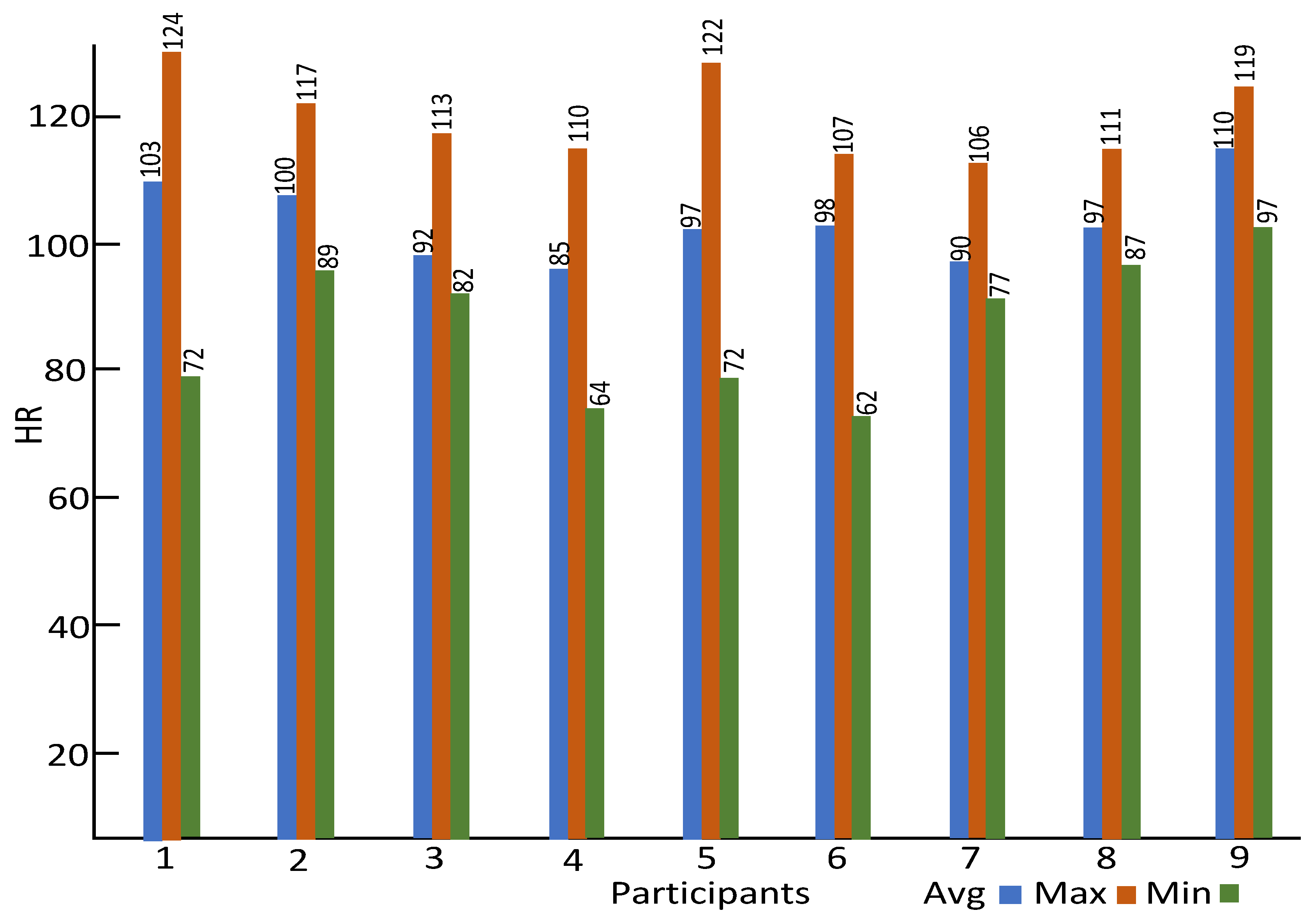

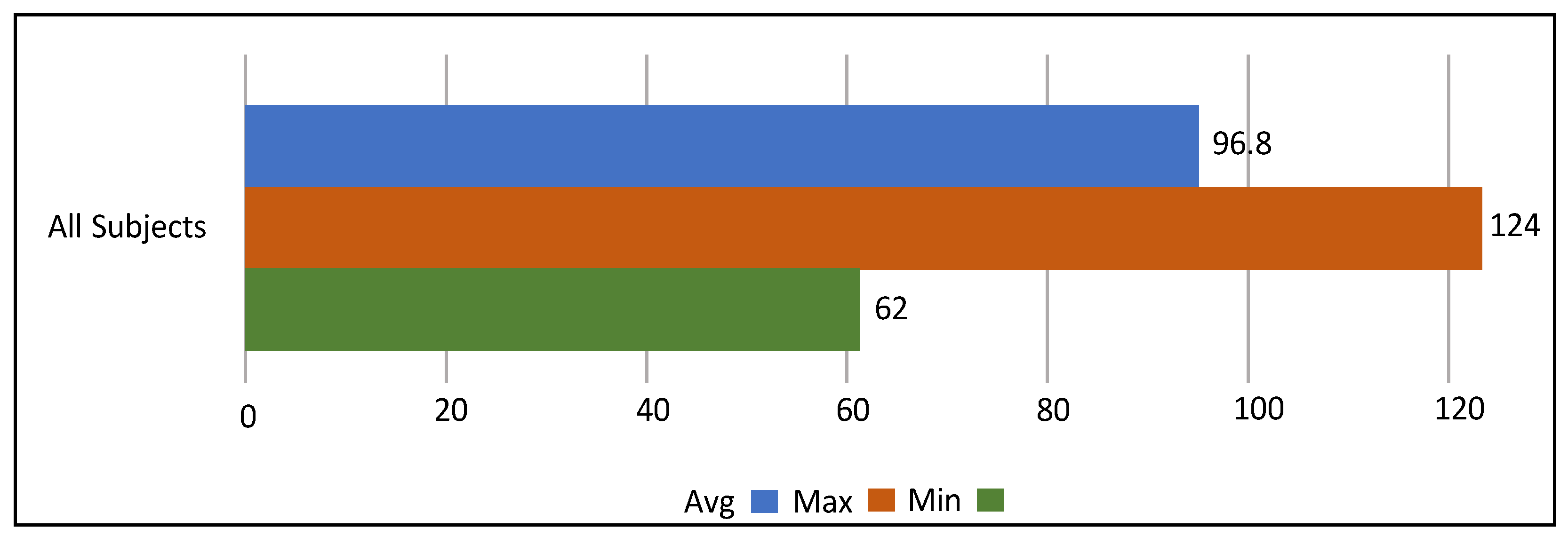

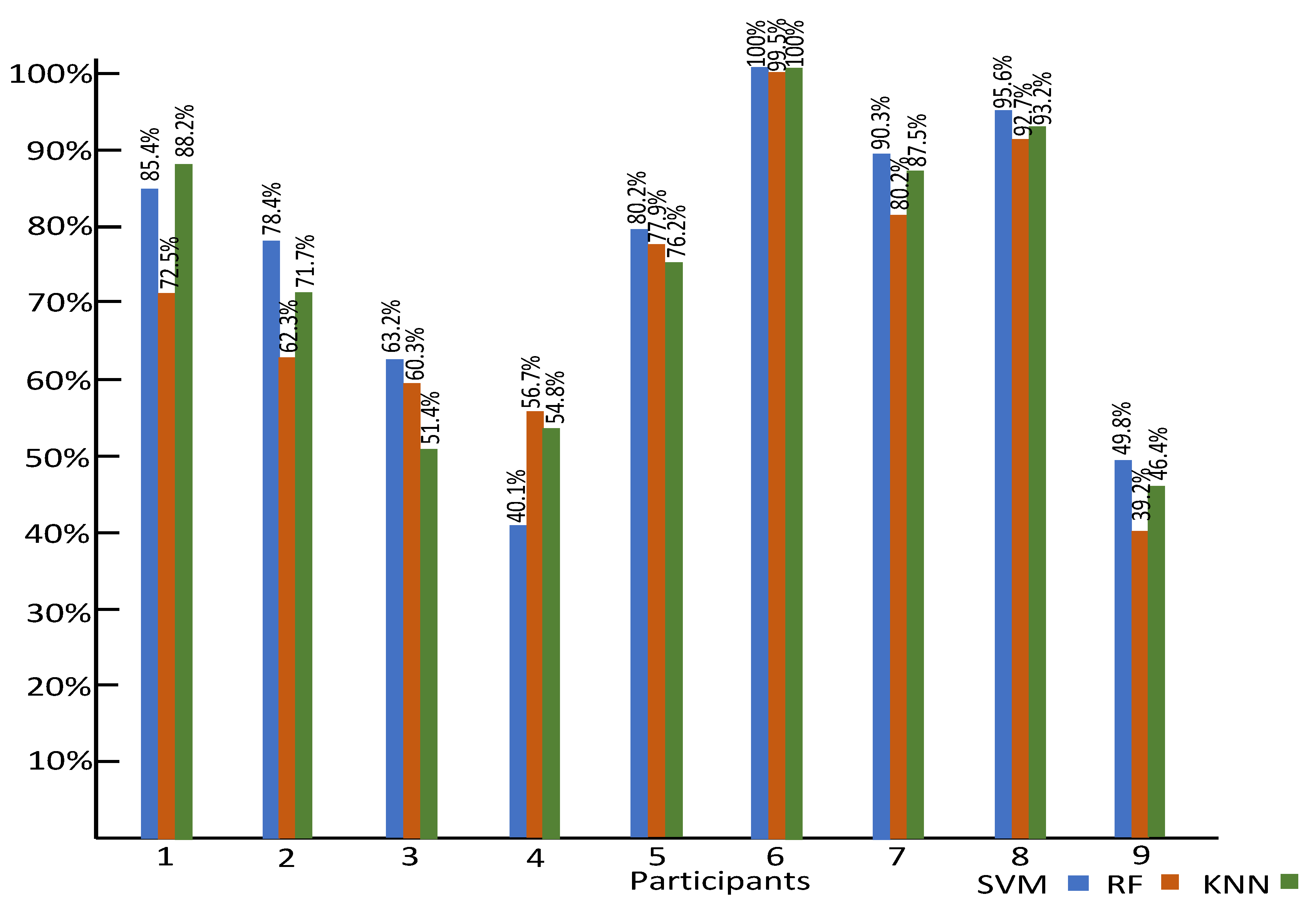

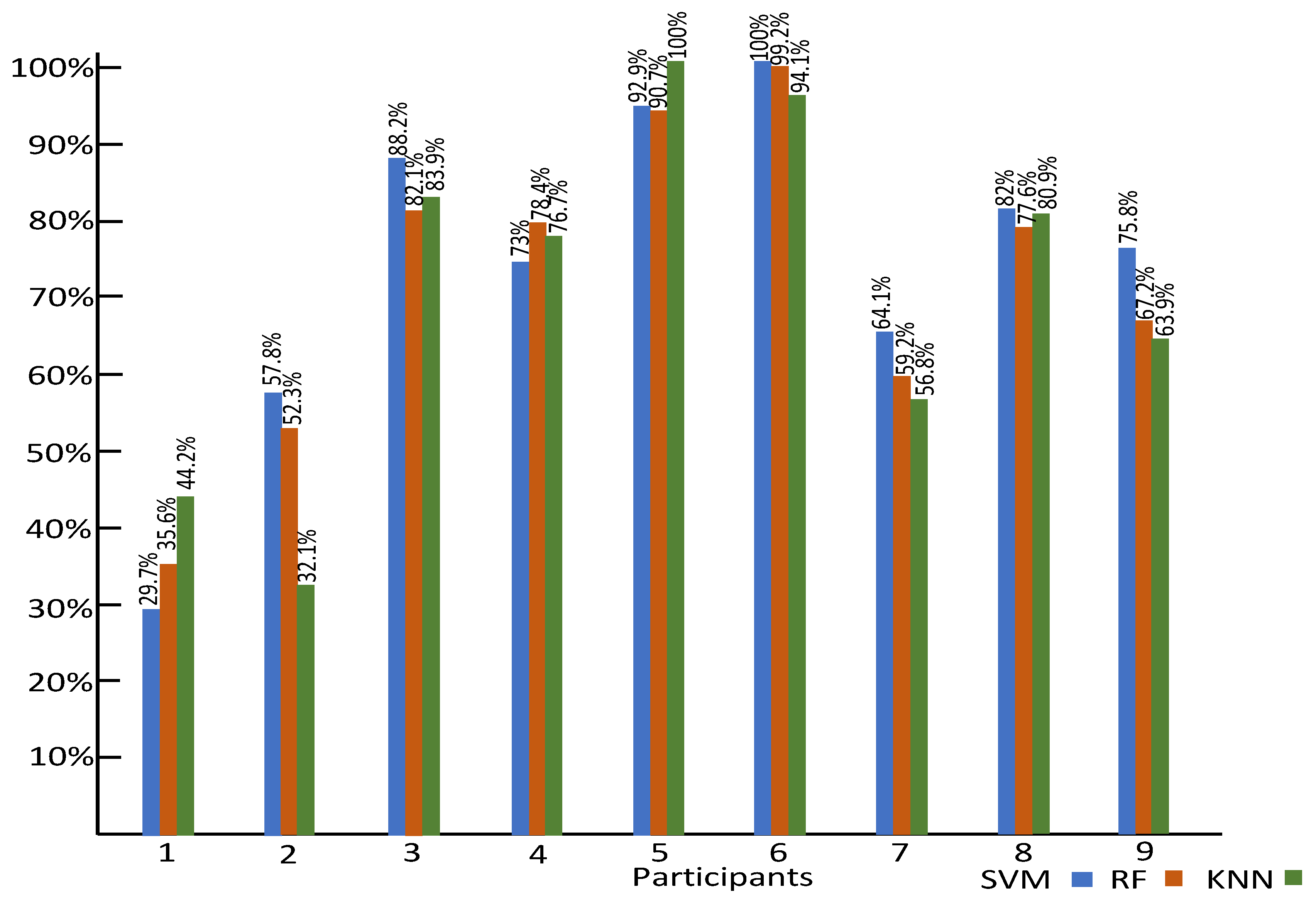

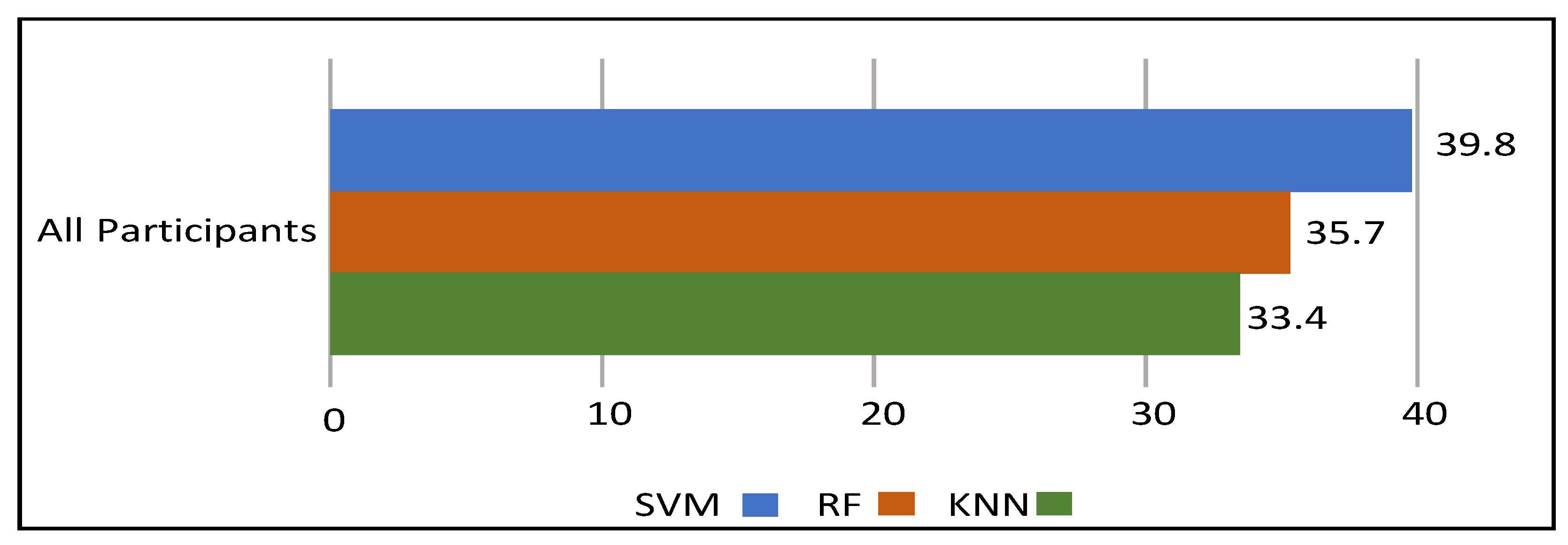

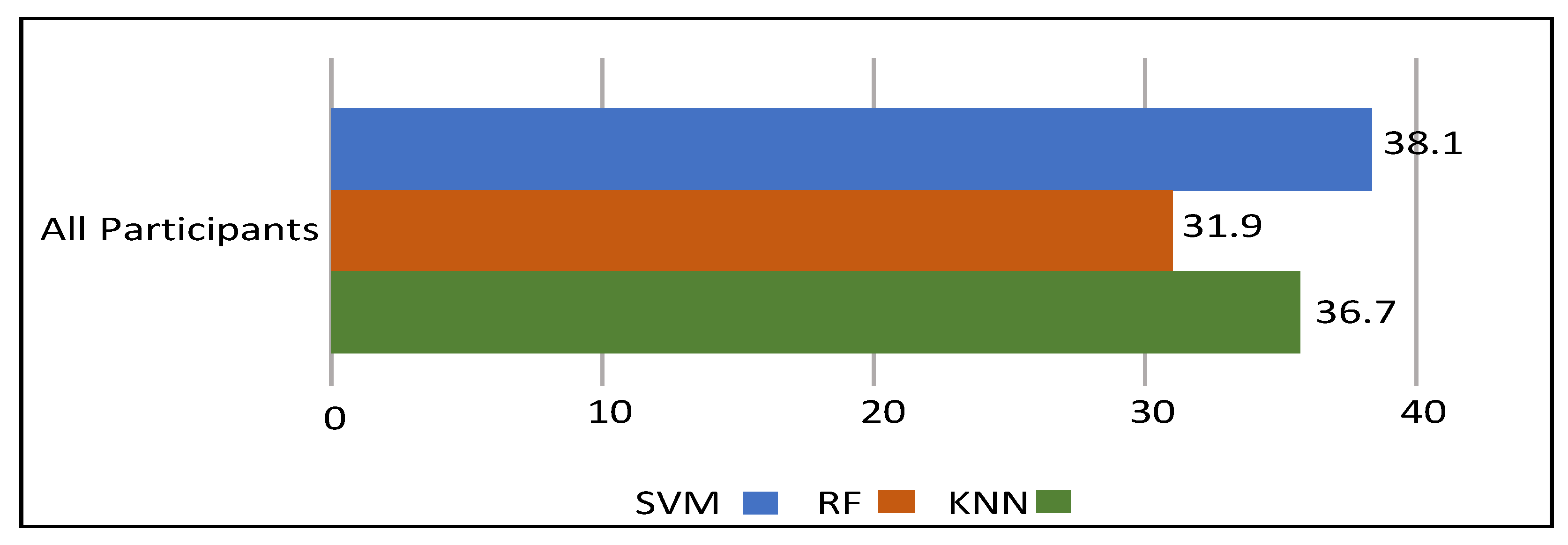

6. Experimental Results and Discussion

7. Comparison with Related Studies

8. Conclusions

Author Biographies

KAMRAN ALI

SACHIN SHAH

CHARLES HUGHES

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FER | Facial Expression Recognition |

| HR | Heart rate |

| DWT | Discrete Wavelet Transform |

| KNN | K-nearest neighbors |

| RF | Random Forest |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

References

- Javed, Hifza, Myounghoon Jeon, and Chung H. Park. Adaptive framework for emotional engagement in child-robot interactions for autism interventions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots, USA, 2018.

- Fioriello, Francesca, et al. A wearable heart rate measurement device for children with autism spectrum disorder. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Ekman, Paul. An argument for basic emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169-200. [CrossRef]

- Britton, A.; Shipley, M.; Malik, M.; Hnatkova, K.; Hemingway, H.; Marmot, M. Changes in Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability Over Time in Middle-Aged Men and Women in the General Population (from the Whitehall II Cohort Study) Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 100, 524–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderas, M.T.; Bolea, J.; Laguna, P.; Vallverdú, M.; Bailón, R. Human emotion recognition using heart rate variability analysis with spectral bands based on respiration In Proceedings of the International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Italy, 2015.

- Richardson, K.; Coeckelbergh, M.; Wakunuma, K.; Billing, E.; Ziemke, T.; Gomez, P.; Vanderborght, B.; Belpaeme, T. Belpaeme. Robot enhanced therapy for children with Autism (DREAM): A social model of autism. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2018, 37, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, P.; Tonacci, A.; Tartarisco, G.; Billeci, L.; Ruta, L.; Gangemi, S.; Pioggia, G. Autism and social robotics: A systematic review. Autism Res. 2016, 9, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scassellati, B., Admoni, H., Matarić, M. Robots for use in autism research Ann. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 14, 275–294.

- Ferari, E., Robins, B., Dautenhahn, K. Robot as a social mediator - a play scenario implementation with children with autism. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Como, Italy, 2009.

- Taylor, M.S. Computer programming with preK1st grade students with intellectual disabilities. J. Spec. Educ. 2018, 52, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M. S. , Vasquez, E., and Donehower, C.Computer programming with early elementary students with Down syndrome. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2017, 32, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landowska, Agnieszka, et al. Automatic emotion recognition in children with autism: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2022, 22.4, 1649. [CrossRef]

- Pollreisz, David, and Nima TaheriNejad. A simple algorithm for emotion recognition, using physiological signals of a smart watch. In Proceedings of the international conference of the ieee engineering in medicine and biology society. South Korea, 2017.

- Liu, Changchun, et al. Affect recognition in robot-assisted rehabilitation of children with autism spectrum disorder. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics and Automation. Italy, 2007.

- Rudovic, O.; Lee, J.; Dai, M.; Schuller, B.; Picard, R.W. Personalized machine learning for robot perception of affect and engagement in autism therapy. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3, eaao6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, A.G.; Taheri, A.; Alemi, M.; Meghdari, A. Human–Robot Facial Expression Reciprocal Interaction Platform: Case Studies on Children with Autism. Soc. Robot. 2018, 10, 179–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossard, C. et al. Children with autism spectrum disorder produce more ambiguous and less socially meaningful facial expressions: An experimental study using random forest classifiers. Mol. Autism 2020, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Coco, M.; Leo, M.; Carcagnì, P.; Spagnolo, P.; Mazzeo, P.L.; Bernava, M.; Marino, F.; Pioggia, G.; Distante, C. A Computer Vision Based Approach for Understanding Emotional Involvements in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops. Italy, 2017.

- Leo, M.; Del Coco, M.; Carcagni, P.; Distante, C.; Bernava, M.; Pioggia, G.; Palestra, G. Automatic Emotion Recognition in Robot-Children Interaction for ASD Treatment. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Chile, 2015.

- Silva, V.; Soares, F.; Esteves, J. Mirroring and recognizing emotions through facial expressions for a RoboKind platform. In Proceedings of the IEEE 5th Portuguese Meeting on Bioengineering, Portugal; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Zhang, K.; Chen, J.; Xu, R.; Gao, L. Design and application of facial expression analysis system in empathy ability of children with autism spectrum disorder. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Science and Intelligence Systems, Online; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.; Soares, F.; Esteves, J.S.; Santos, C.P.; Pereira, A.P. Fostering Emotion Recognition in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landowska, A.; Robins, B. Robot Eye Perspective in Perceiving Facial Expressions in Interaction with Children with Autism. In Web, Artificial Intelligence and Network Applications; Barolli, L., Amato, F., Moscato, F., Enokido, T., Takizawa, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1287–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Bhat, A.; Barmaki, R. A Two-stage Multi-Modal Affect Analysis Framework for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.09199. [Google Scholar]

- Marinoiu, E.; Zanfir, M.; Olaru, V.; Sminchisescu, C. 3D Human Sensing, Action and Emotion Recognition in Robot Assisted Therapy of Children with Autism. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 2158–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Santhoshkumar, R.; Kalaiselvi Geetha, M. Emotion Recognition System for Autism Children using Non-verbal Communication. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng 2019, 8, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Conn, K.; Sarkar, N.; Stone, W. Online Affect Detection and Adaptation in Robot Assisted Rehabilitation for Children with Autism. In Proceedings of the RO-MAN 2007–The 16th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Jeju, Korea, 26–29 August 2007; pp. 588–593. [Google Scholar]

- Fadhil, T.Z.; Mandeel, A.R. Live Monitoring System for Recognizing Varied Emotions of Autistic Children. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Advanced Science and Engineering (ICOASE), Duhok, Iraq, 9–11 October 2018; pp. 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sarabadani, S.; Schudlo, L.C.; Samadani, A.; Kushki, A. Physiological Detection of Affective States in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput 2018, 11, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusli, N.; Sidek, S.N.; Yusof, H.M.; Ishak, N.I.; Khalid, M.; Dzulkarnain, A.A.A. Implementation of Wavelet Analysis on Thermal Images for Affective States Recognition of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 120818–120834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Palma, S.; Tonacci, A.; Narzisi, A.; Domenici, C.; Pioggia, G.; Muratori, F.; Billeci, L. Monitoring of autonomic response to sociocognitive tasks during treatment in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders by wearable technologies: A feasibility study. Comput. Biol. Med. 2017, 85, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Conn, K.; Sarkar, N.; Stone, W. Physiology-based affect recognition for computer-assisted intervention of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J.-Hum. Stud. 2008, 66, 662–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen NT, Nguyen NV, My Huynh T, Tran, Nguyen Binh T. A potential approach for emotion prediction using heart rate signals. In Proceedings of the international conference on knowledge and systems engineering, Vietnam, 2017.

- Shu, L.; Yu, Y.; Chen, W.; Hua, H.; Li, Q.; Jin, J.; Xu, X. Wearable emotion recognition using heart rate data from a smart bracelet. Sensors 2020, 20, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulagang, Aaron Frederick, James Mountstephens, and Jason Teo. Multiclass emotion prediction using heart rate and virtual reality stimuli J. Big Data 2021, 8, 1-12.

- Lei, Jing, Johannan Sala, and Shashi K. Jasra. Identifying correlation between facial expression and heart rate and skin conductance with iMotions biometric platform. J. Emerg. Forensic Sci. Res. 2017, 2, 53-83.

- Ali, Kamran, and Charles E. Hughes. Facial Expression Recognition By Using a Disentangled Identity-Invariant Expression Representation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Online, 2020.

- Castellanos, Nazareth P., and Valeri A. Makarov. Recovering EEG brain signals: Artifact suppression with wavelet enhanced independent component analysis J. Neurosci. Methods 2006, 158, 300-312.

- Dimoulas, C.; Kalliris, G.; Papanikolaou, G.; Kalampakas, A. Long-term signal detection, segmentation and summarization using wavelets and fractal dimension: A bioacoustics application in gastrointestinal-motility monitoring. Comput. Biol. Med. 2007, 37, 438–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glavinovitch, A.; Swamy, M.; Plotkin, E. Wavelet-based segmentation techniques in the detection of microarousals in the sleep eeg. 48th Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems, 2005.

| Ref. | Related Work |

Signal Type | Subject Number |

Stimulation Materials |

Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | Grossard et al. |

Video | 36 | Imitation of facial expressions of an avatar presented on the screen |

Accuracy: 66.43 % (neutral, happy, sad, anger) |

| [18] | Coco et al. |

Video | 5 | Video | Entropy score: (happiness: 1776, fear: 1574, sadness: 1644) |

| [25] | Marinoiu et al. |

Body posture videos |

7 | Robot- assisted therapy sessions |

RMSE: (valence: 0.099, arousal: 0.107) |

| [26] | Kumar et al. |

Gesture videos |

10 | Unknown | F-Measure: (angry: 95.1%, fear: 99.1%, happy: 95.1%, neutral: 99.5%, sad: 93.7%) |

| [14] | Liu et al. |

Skin conductance |

4 | Computer tasks |

Accuracy: 82% |

| [29] | Sarabadani et al. |

Respiration | 15 | Images | Accuracy: (low/positive vs. low/negative: 84.5% and high/positive vs. high negative: 78.1%) |

| [30] | Rusli et al. |

Temperature (thermal imaging) |

23 | Video | Accuracy: 88% |

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 828 s | 846 s | 786 s | 540 s | 660 s | 480 s | 583 s | 611 s | 779 s |

| Author | Participants | Stimuli | Classifer | No. Classes | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shu et al. [34] | 25 | China Emotional Video Stimuli (CEVS) |

Gradient boosting decision tree |

3 | 84 % |

| Bulagang et al. [35] |

20 | Virtual reality (VR) 360° videos |

SVM, KNN, RF |

4 | 100 % for intra-subject and 46.7 % for inter-subject |

| Nguyen et al. [33] |

5 | Android application |

SVM | 3 | 79 % |

| Ours | 9 | Realtime interaction with avatar |

SVM, KNN, RF | 3 | 100 % for intra-subject and 39.8 % for inter-subject |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).