Submitted:

19 April 2023

Posted:

21 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

- ▸

- Remote monitoring for MARPOL Annex VI in Belgium.

- ▸

- Effect of emission regulations from ocean going vessels.

- ▸

- Impact from emissions from ocean going vessels on inland pollution.

- ▸

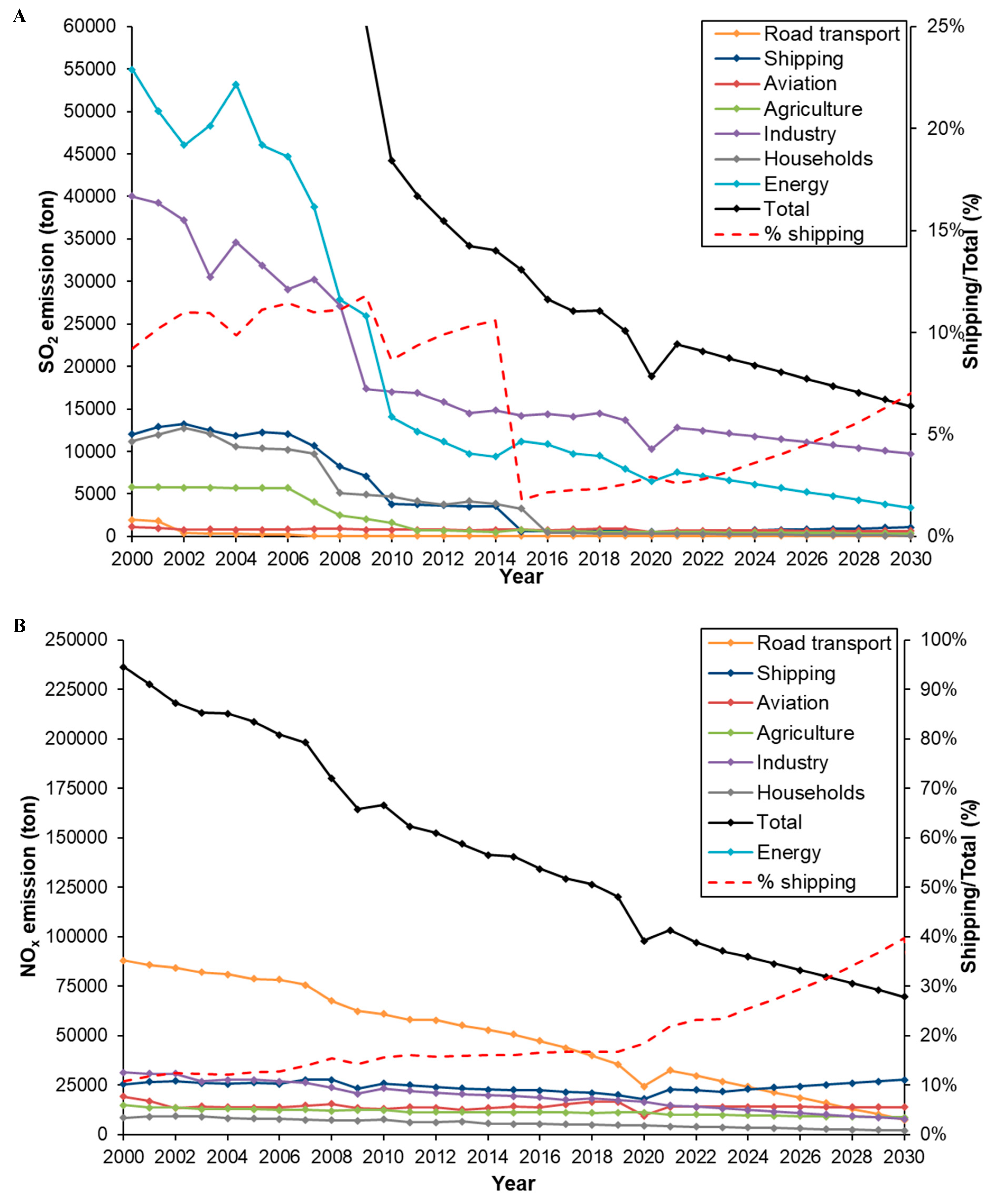

- Trends of SO2 and NOx emissions from ocean going vessels.

- ▸

- Emissions from ships equipped with Exhaust Gas Cleaning Systems

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Belgian Coastguard Aircraft and Sniffer Sensor

2.1.1. Sniffer Sensor

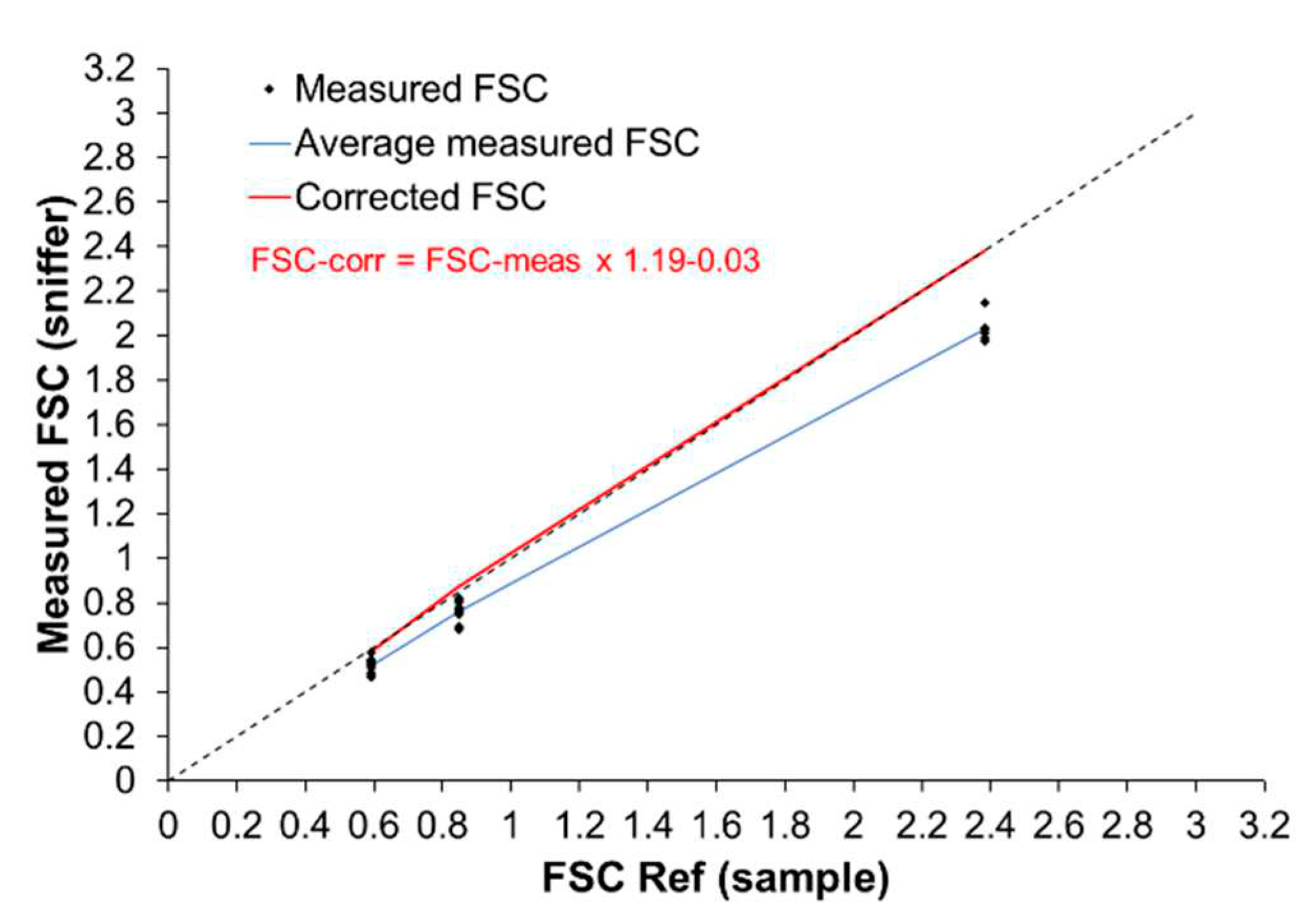

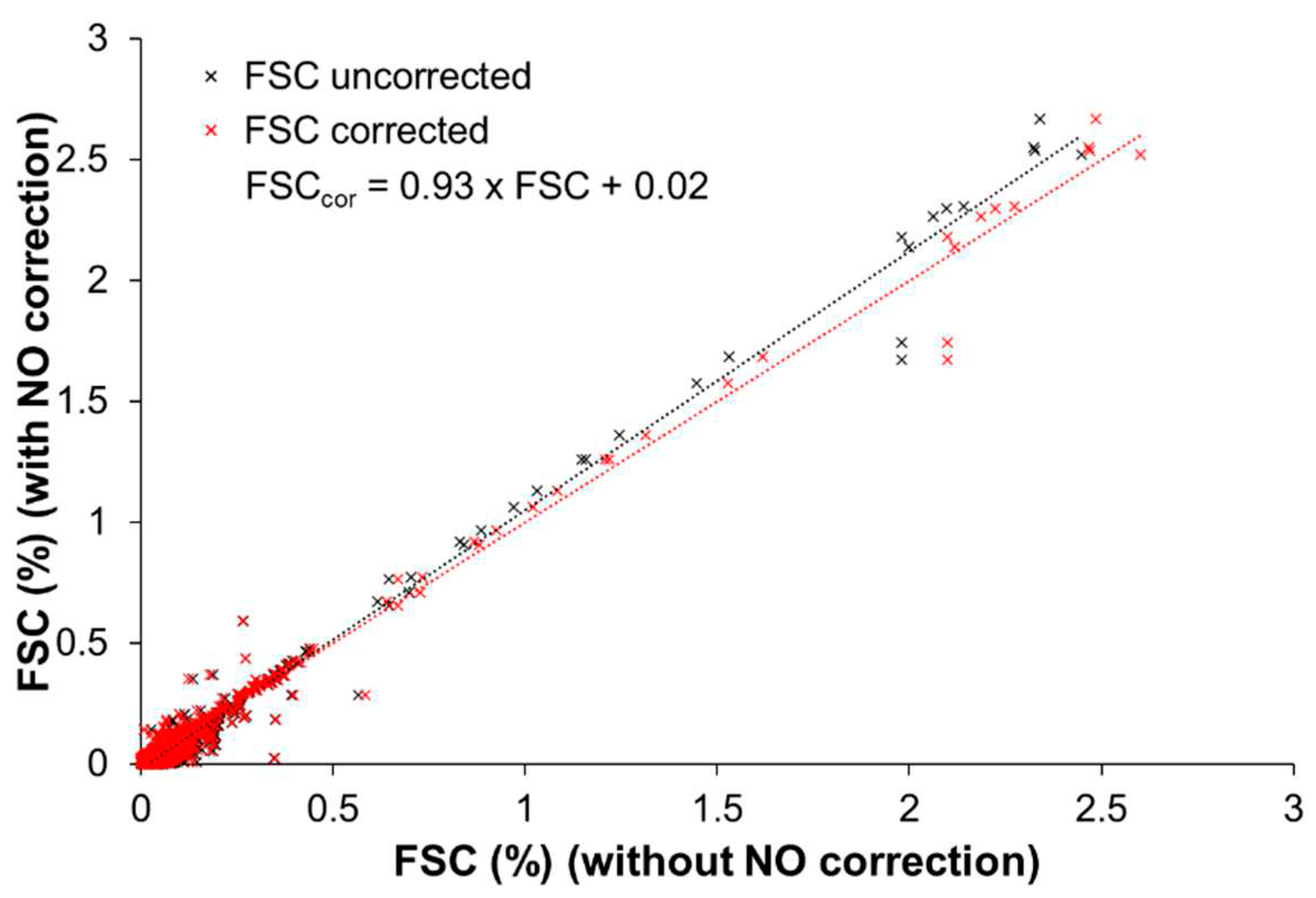

2.1.2. FSC Measurements

2.1.3. NOx Measurements

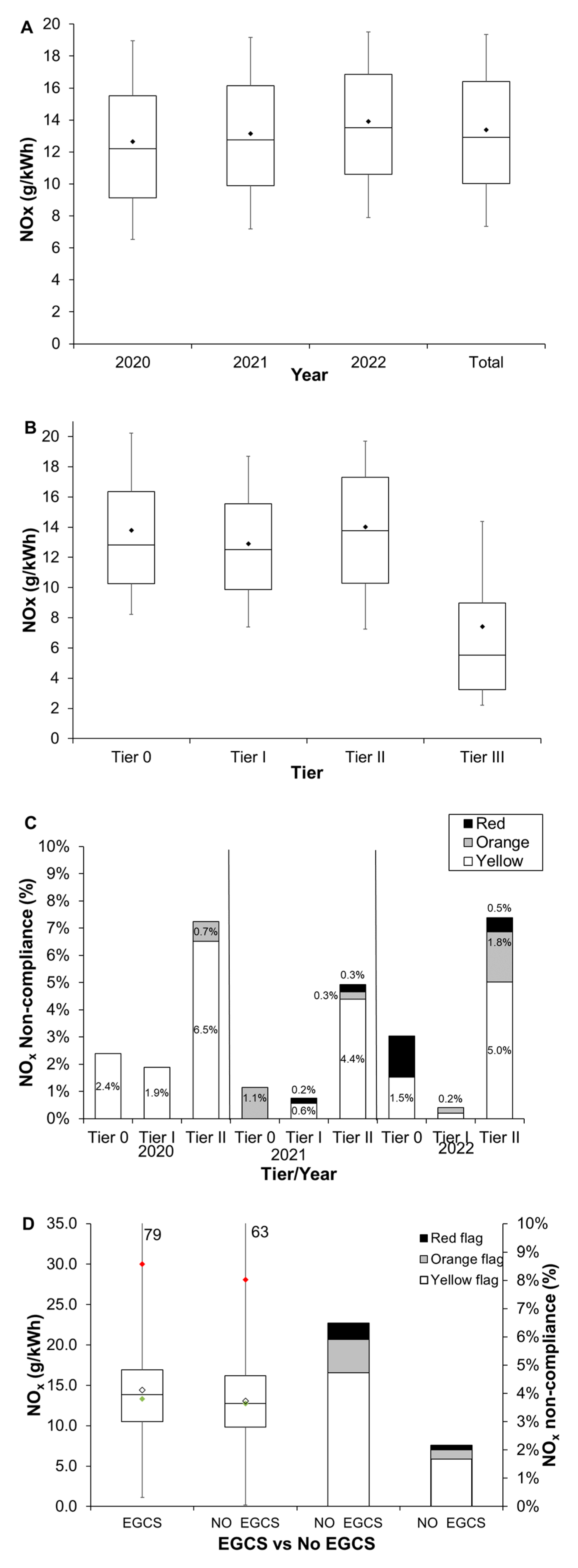

2.1.4. Measurement Quality, Uncertainty and Reporting Thresholds

2.2. Thetis-EU

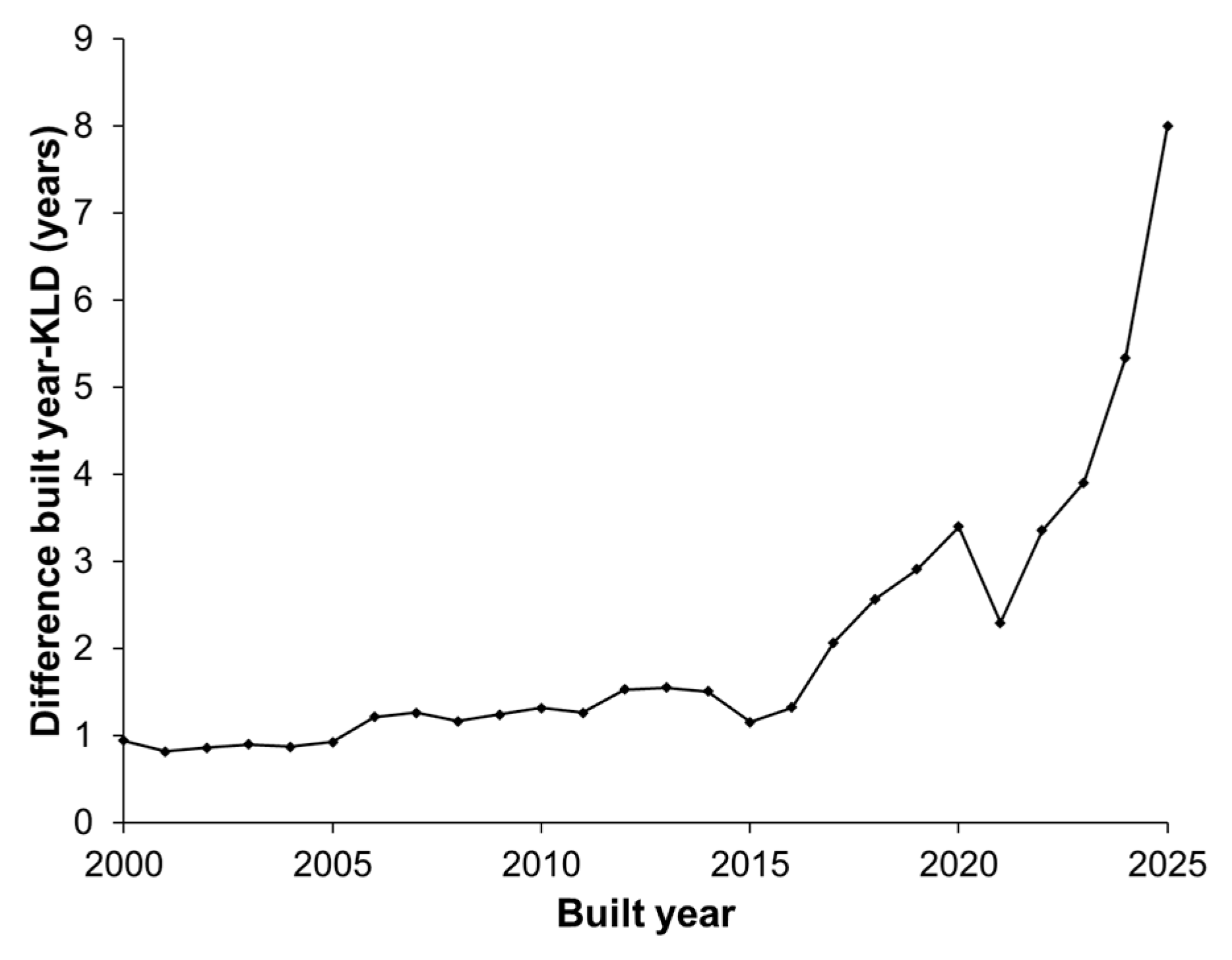

2.2.1. Keel Laying Date

2.2.2. EGCS Data

2.3. Inland Air Quality Measurement Data

2.3.1. Inland Coastal Data and Non-Coastal Data

2.3.2. Trend Analysis by Emission Source

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cromar, K.; Lazrak, N. Risk Communication of Ambient Air Pollution in the WHO European Region: Review of Air Quality Indexes and Lessons Learned; Copenhagen, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, R.; Chen, H.; Szyszkowicz, M.; Fann, N.; Hubbell, B.; Pope, C.A.; Apte, J.S.; Brauer, M.; Cohen, A.; Weichenthal, S.; et al. Global Estimates of Mortality Associated with Long-Term Exposure to Outdoor Fine Particulate Matter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 9592–9597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EEA Air Quality in Europe 2022. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2022 (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Byčenkienė, S.; Khan, A.; Bimbaitė, V. Impact of PM2.5 and PM10 Emissions on Changes of Their Concentration Levels in Lithuania: A Case Study. Atmosphere (Basel) 2022, 13, 1793. [CrossRef]

- EEA Indicator Assessment - Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) Emissions. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/indicators/eea-32-nitrogen-oxides-nox-emissions-1/assessment.2010-08-19.0140149032-3 (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Corbett, J.J.; Fischbeck, P.S.; Pandis, S.N. Global Nitrogen and Sulfur Inventories for Oceangoing Ships. Journal of Geophysical Research Atmospheres 1999, 104, 3457–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J.J.; Wang, C.; Winebrake, J.J.; Green, E. Allocation and Forecasting of Global Ship Emissions ANNEX Allocation and Forecasting of Global Ship Emissions Prepared for the Clean Air Task Force; 2007.

- Corbett, J.J.; Fischbeck, P.S. Emissions from Ships. Science (1979) 1997, 278, 823–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J.J.; Koehler, H.W. Updated Emissions from Ocean Shipping. J Geophys Res 2003, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO Third IMO GHG Study 2014 Executive Summary and Final Report; 2015.

- Faber, J.; Hanayama, S.; Zhang, S.; Pereda, P.; Bryan Comer; Elena Hauerhof; Wendela Schim van der Loeff; Tristan Smith; Yan Zhang; Hiroyuko Kosaka; et al. In Fourth IMO GHG Study 2020 Full Report; London, 2021.

- EMSA Tackling Emissions - Air Pollutants. Available online: https://www.emsa.europa.eu/tackling-air-emissions/air-pollutants.html (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Zhang, Y.; Eastham, S.D.; Lau, A.K.; Fung, J.C.; Selin, N.E. Global Air Quality and Health Impacts of Domestic and International Shipping. Environmental Research Letters 2021, 16, 084055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofiev, M.; Winebrake, J.J.; Johansson, L.; Carr, E.W.; Prank, M.; Soares, J.; Vira, J.; Kouznetsov, R.; Jalkanen, J.P.; Corbett, J.J. Cleaner Fuels for Ships Provide Public Health Benefits with Climate Tradeoffs. Nat Commun 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Fu, M.; Jin, X.; Shang, Y.; Shindell, D.; Faluvegi, G.; Shindell, C.; He, K. Health and Climate Impacts of Ocean-Going Vessels in East Asia. Nat Clim Chang 2016, 6, 1037–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, M.; Rizza, V.; Tobías, A.; Carr, E.; Corbett, J.; Sofiev, M.; Karanasiou, A.; Buonanno, G.; Fann, N. Estimated Health Impacts from Maritime Transport in the Mediterranean Region and Benefits from the Use of Cleaner Fuels. Environ Int 2020, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Air Quality Guidelines : Global Update 2005 : Particulate Matter, Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, and Sulfur Dioxide.; World Health Organization, 2006; ISBN 9289021926.

- Schwarzkopf, D.A.; Petrik, R.; Matthias, V.; Quante, M.; Yu, G.; Zhang, Y. Comparison of the Impact of Ship Emissions in Northern Europe and Eastern China. Atmosphere (Basel) 2022, 13, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 1978 Relating Thereto (Adopted 17 February 1978 (MARPOL), in Force 2 October 1983) 1340 UNTS 61, as Amended; International Maritime Organization, 1978.

- IMO Protocol of 1997 to Amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships of 2 November 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 17 February 1978, London, 1997, into Force on 19 May 2005 and Amended (Revised MARPOL Annex VI), Resolution MEPC.176(58) Adopted on 10 October 2008, in Force on 1 July 2010; International Maritime Organization, London, 1997.

- IMO Status Of IMO Treaties : Comprehensive Information on the Status of Multilateral Conventions and Instruments in Respect of Which the International Maritime Organization or Its Secretary-General Performs Depositary or Other Functions. Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/StatusOfConventions.aspx (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- MEPC List of Special Areas, Emission Control Areas and Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas; Marine Environmental Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, 2018; pp. 1–5;

- MEPC Amendments to the Annex of the Protocol of 1997 to Amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 1978 Relating Thereto. Amendments to MARPOL Annex VI (Designation of the Baltic Sea and the North Sea Emission Control Areas for NOX Tier III Control), Resolution MEPC.268(71) Adopted on 7 July 2017, in Force on 1 January 2019; Marine Environment Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2017.

- MEPC Proposal to Designate the North Sea as an Emission Control Area for Nitrogen Oxides (Submitted by Belgium et al.), Resolution MEPC.70/5/Rev.1; Marine Environment Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2016; pp. 1–71.

- MEPC Amendments to the Annex of the Protocol of 1997 to Amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 1978 Relating Thereto (Designation of the United States Caribbean Sea Emission Control Area and Exemption of Certain Ships Operating in the North American Emission Control Area and the United States Caribbean Sea Emission Control Area under Regulations 13 and 14 and Appendix VII of MARPOL Annex VI), Resolution MEPC 202(62); Marine Environment Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2011; pp. 2–13.

- MEPC Amendments to the Annex of the Protocol of 1997 to Amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 1978 Relating Thereto; Marine Environment Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, 2010; pp. 1–11.

- MEPC Amendments to the Annex of the Protocol of 1997 to Amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 1978 Relating Thereto, Resolution MEPC.132(53), Adopted on 22 July 2005; Marine Environmental Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2005; pp. 1–16.

- Endres, S.; Maes, F.; Hopkins, F.; Houghton, K.; Mårtensson, E.M.; Oeffner, J.; Quack, B.; Singh, P.; Turner, D. A New Perspective at the Ship-Air-Sea-Interface: The Environmental Impacts of Exhaust Gas Scrubber Discharge. Front Mar Sci 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEPC 2015 Guidelines for Exhaust Gas Cleaning Systems, Resolution MEPC.259(68) Adopted on 15 May 2015, Superseded by the 2021 Guidelines for Exhaust Gas Cleaning Systems, Resolution MEPC.340(77) Adopted on 26 November 2021 for EGCS Installed on Ships Constructed or Delivered on or after 1 June 2021, or the Actual Delivery of EGCS to the Ship on or after 1 June 2021.; Marine Environment Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2015; pp. 1–23.

- Johansson, L.; Jalkanen, J.-P.; Kukkonen, J. Global Assessment of Shipping Emissions in 2015 on a High Spatial and Temporal Resolution. Atmos Environ 2017, 167, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalkanen, J.-P.; Johansson, L.; Kukkonen, J. A Comprehensive Inventory of Ship Traffic Exhaust Emissions in the European Sea Areas in 2011. Atmos Chem Phys 2016, 16, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEPC Effective Date of Implementation of the Fuel Oil Standard in Regulation 14.1.3 of MARPOL Annex VI, Resolution MEPC.280(70) Adopted on 28 October 2016; Marine Environment Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2016; pp. 1–3.

- MEPC Amendments to the Annex of the Protocol of 1997 to Amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 1978 Relating Thereto (Prohibition on the Carriage of Non-Compliant Fuel Oil for Combustion Purposes for Propulsion or Operation on Board a Ship), Resolution MEPC.305(73) Adopted on 26 October 2018, in Force on 1 March 2020; Marine Environment Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2018; pp. 1–5.

- EU Directive 2005/35/EC on Ship-Source Pollution and on the Introduction of Penalties for Infringements, OJ L 255/11, 30.09.2005; See Revision of Directive 2005/35/EC at at HHttps://Www.Europarl.Europa.Eu/Legislative-Train/Theme-a-European-Green-Deal/File-Revision-of-the-Ship-Source-Pollution-Directive.

- EU Directive (EU) 2016/802 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2016 Relating to a Reduction in the Sulphur Content of Certain Liquid Fuels, 12.05.2016; The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 2016; pp. 58–78.

- Royal Decree Koninklijk Besluit Inzake Milieuvriendelijke Scheepvaart BS 21.08.2020 (Chapter 4 on Sulphur), Amended by KB 4 November 2020, BS 17.11.2020 (Adding Chapter 6 on NOx); Belgisch Staatsblad, 21/08/2020: Belgium, 2020; pp. 63339–63386.

- Royal Decree Koninklijk Besluit (KB) van 27 April 2007 Betreffende de Voorkoming van Luchtverontreiniging Door Schepen En de Vermindering van Het Zwavelgehalte van Sommige Scheepsbrandstoffen. Belgisch Staatsblad (BS), 08.05.2007, Amended by KB of 19 December 2014, BS 24.12.2014 and KB of 20 December 2019, BS 30.12.2019. This KB Has Been Cancelled and Replaced by KB of 15 Juli 2020 Inzake Milieuvriendelijke Scheepvaart; Belgisch Staatsblad, 27/04/2007: Belgium, 2007; pp. 25199–25203.

- EU Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/253 of Laying down the Rules Concerning the Sampling and Reporting under Council Directive 1999/32/EC as Regards the Sulphur Content of Marine Fuels, OJ L 41/55, 17.02.2015. References to the Repealed Directive 1999/32/EC Shall Be Construed as References to Directive 2016/802 (Art. 19 Directive 2016/802); The European Commission, 2015; pp. 45–59; 16 February.

- MEPC Amendments to the Annex of the Protocol of 1997 to Amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 1978 Relating Thereto (Procedures for Sampling and Verification of the Sulphur Content of Fuel Oil and the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI)), Resolution MEPC.324(75) Adopted on 20 November 2020, in Force on 1 April 2022; Marine Environmental Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2020.

- MEPC Amendments to the Annex of the Protocol of 1997 to Amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 1978 Relating Thereto (2021 Revised MARPOL Annex VI), Resolution MEPC.328(76), in Force on 1 November 2022; Marine Environmental Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, 2022.

- MEPC Amendments to the Technical Code on Control of Emission of Nitrogen Oxides from Marine Diesel Engines (NOx Technical Code 2008), Resolution MEPC.177(58) of 10 October 2008, in Force on 1 July 2010; Marine Environmental Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2008.

- MEPC Amendments to the Annex of the Protocol of 1997 to Amend the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as Modified by the Protocol of 1978 Relating Thereto (Revised MARPOL Annex VI), Resolution MEPC.176(58) of 10 October 2008, in Force on 1 July 2010; Marine Environment Protection Committee: International Maritime Organization, London, 2008; pp. 1–46.

- Lagring, R.; Degraer, S.; de Montpellier, G.; Jacques, T.; Van Roy, W.; Schallier, R. Twenty Years of Belgian North Sea Aerial Surveillance: A Quantitative Analysis of Results Confirms Effectiveness of International Oil Pollution Legislation. Mar Pollut Bull 2012, 64, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagring, R.; Degraer, S.; de Montpellier, G.; Jacques, T.; Van Roy, W.; Schallier, R. Twenty Years of Belgian North Sea Aerial Surveillance: A Quantitative Analysis of Results Confirms Effectiveness of International Oil Pollution Legislation. Mar Pollut Bull 2012, 64, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal Decree Law. Article 4.2.4.5. of the Belgian Shipping Code (Wet Tot Invoering van Het Belgisch Scheepvaartwetboek) of 01.08.2019; Belgisch Staatsblad: Belgium, 2019; pp. 75432–75808.

- Mellqvist, J.; Beecken, J.; Conde, V.; Ekholm, J. Surveillance of Sulfur Emissions from Ships in Danish Waters, Report to the Danish Environmental Protection Agency; Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017.

- Van Roy, W.; Van Nieuwenhove, A.; Scheldeman, K.; Van Roozendael, B.; Schallier, R.; Mellqvist, J.; Maes, F. Measurement of Sulfur-Dioxide Emissions from Ocean-Going Vessels in Belgium Using Novel Techniques. Atmosphere (Basel) 2022, 13, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzani Lööv, J.M.; Alfoldy, B.; Gast, L.F.L.; Hjorth, J.; Lagler, F.; Mellqvist, J.; Beecken, J.; Berg, N.; Duyzer, J.; Westrate, H.; et al. Field Test of Available Methods to Measure Remotely SOx and NOx Emissions from Ships. Atmos Meas Tech 2014, 7, 2597–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roy, W.; Schallier, R.; Van Roozendael, B.; Scheldeman, K.; Van Nieuwenhove, A.; Maes, F. Airborne Monitoring of Compliance to Sulfur Emission Regulations by Ocean-Going Vessels in the Belgian North Sea Area. Atmos Pollut Res 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roy, W.; Schallier, R.; Scheldeman, K.; Van Roozendael, B.; Van Nieuwenhove, A.; Maes, F. Airborne Monitoring of Compliance to Sulfur Emission Regulations by Ocean-Going Vessels in the Belgian North Sea Area. Atmos Pollut Res 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beecken, J.; Mellqvist, J.; Salo, K.; Ekholm, J.; Jalkanen, J.P. Airborne Emission Measurements of SO2, NOx and Particles from Individual Ships Using a Sniffer Technique. Atmos Meas Tech 2014, 7, 1957–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellqvist, J.; Ekholm, J.; Salo, K.; Beecken, J. Identification of Gross Polluting Ships to Promote a Level Playing Field Withing the Shipping Sector; 2014.

- Beecken, J.; Mellqvist, J.; Salo, K.; Ekholm, J.; Jalkanen, J.P.; Johansson, L.; Litvinenko, V.; Volodin, K.; Frank-Kamenetsky, D.A. Emission Factors of SO2, NOx and Particles from Ships in Neva Bay from Ground-Based and Helicopter-Borne Measurements and AIS-Based Modelling. Atmos Chem Phys 2015, 15, 5229–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beecken, J.; Irjala, M.; Weigelt, A.; Conde, V.; Mellqvist, J.; Proud, R.; Deakin, A.; Knudsen, B.; Timonen, H.; Sundström, A.-M.; et al. SCIPPER Project D2.1 Review of Available Remote Systems for Ship Emission Measurements; 2019.

- Alföldy, B.; Lööv, J.B.; Lagler, F.; Mellqvist, J.; Berg, N.; Beecken, J.; Weststrate, H.; Duyzer, J.; Bencs, L.; Horemans, B.; et al. Measurements of Air Pollution Emission Factors for Marine Transportation in SECA. Atmos Meas Tech 2013, 6, 1777–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roy, W.; Scheldeman, K.; Van Nieuwenhove, A.; Van Roozendael, B.; Schallier, R.; Vigin, L.; Maes, F. Airborne Monitoring of Compliance to NOx Emission Regulations from Ocean-Going Vessels in the Belgian North Sea Area. Atmos Pollut Res 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, A. Sulphur Emission Compliance Monitoring of Ships in German Waters – Results from Five Years of Operation. In Proceedings of the Shipping and the Environment, Symposium on Scenarios and Policy Options for Sustainable Shipping (POL); BSH: Goteborg, October 8 2019.

- Krause, K.; Wittrock, F.; Richter, A.; Busch, D.; Bergen, A.; Burrows, J.P.; Freitag, S.; Halbherr, O. Determination of NOx Emission Rates of Inland Ships from Onshore Measurements. Atmos Meas Tech 2023, 16, 1767–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, N.; Mellqvist, J.; Jalkanen, J.P.; Balzani, J. Ship Emissions of SO 2 and NO 2: DOAS Measurements from Airborne Platforms. Atmos Meas Tech 2012, 5, 1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

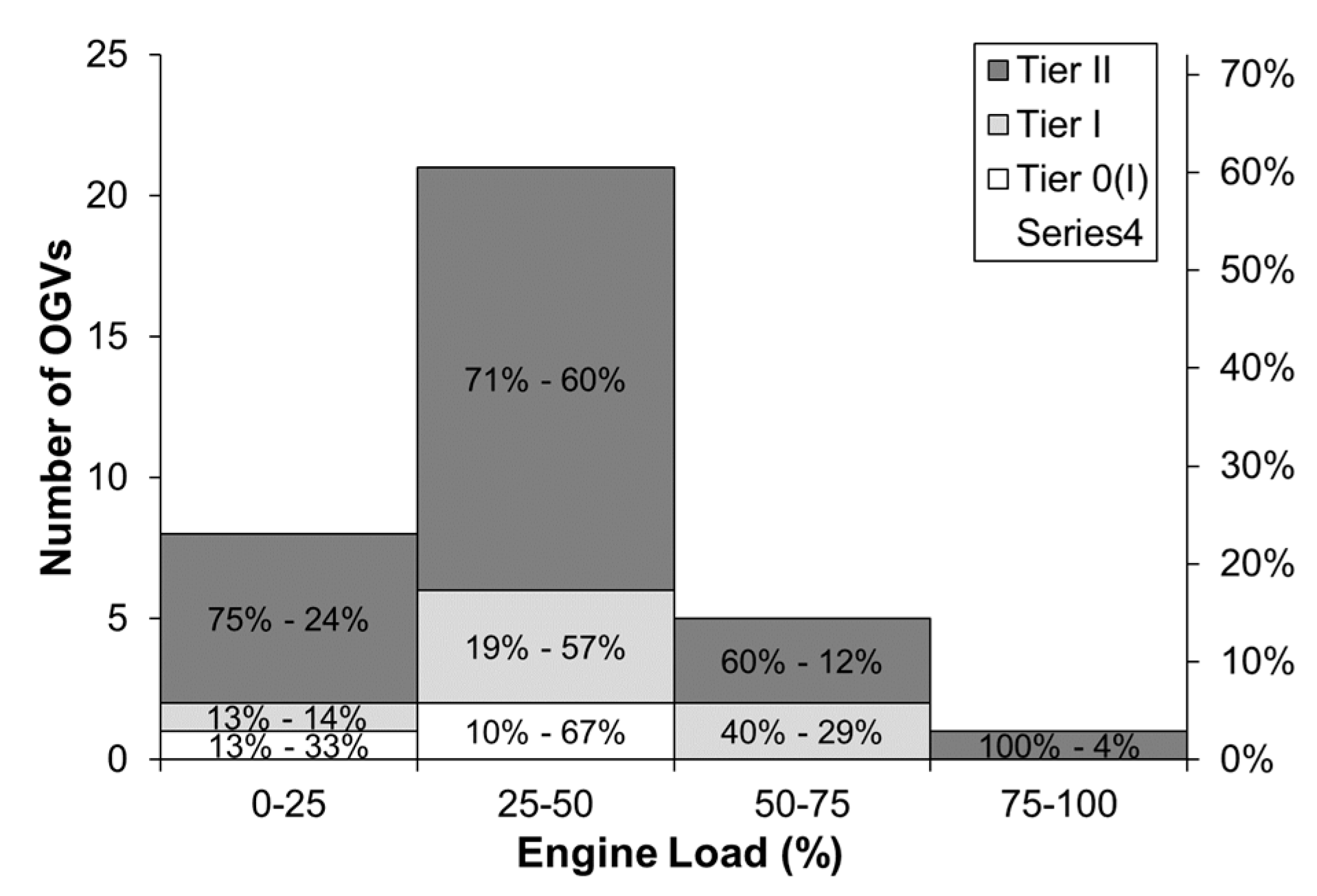

- Cheng, C.W.; Hua, J.; Hwang, D.S. Nox Emission Calculations for Bulk Carriers by Using Engine Power Probabilities as Weighting Factors. J Air Waste Manage Assoc 2017, 67, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirjola, L.; Pajunoja, A.; Walden, J.; Jalkanen, J.P.; Rönkkö, T.; Kousa, A.; Koskentalo, T. Mobile Measurements of Ship Emissions in Two Harbour Areas in Finland. Atmos Meas Tech 2014, 7, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asariotis, W.J.R.; Assaf, M.; Ayala, G.; Ayoub, A.; Benamara, H.; Chantrel, D.; Hoffmann, J.; Larouche-Maltais, A.; Premti, A.; Rodríguez, L.; et al. Review of Maritime Transport 2020.; 2020.

- WINGD Low-Speed Engines 2017 Simply a Better Different; 2017.

- WINGD Engine Selection for Very Large Container Vessels; Winterthur, 2016.

- MAN B&W MAN B&W G95ME-C9.2-GIIMO Tier II Project Guide. 0.5 2014, 346.

- MAN B&W MAN B&W S90ME-C8.2-GI IMO Tier II Project Guide. 0.5 2014, 1–362.

- Acomi, N.; Cristian Acomi, O. The Influence of Different Types of Marine Fuel over the Energy Efficiency Operational Index. In Proceedings of the Energy Procedia; Elsevier Ltd., 2014; Volume 59, pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- European Maritime Safety Agency Https://Www.Emsa.Europa.Eu/Thetis-Eu.Html.

- EMSA Thetis-EU.

- VMM Air Quality Measurements in Flanders Available online:. Available online: https://www.vmm.be/lucht/stikstof/uitstoot-stikstofoxiden (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- UNCTAD Https://Unctad.Org/Rmt2022 Available online:. Available online: https://unctad.org/rmt2022 (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Gardner, M.J.; Altman, D.G. Estimating with Confidence. BMJ 1988, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprinthall, R.C. Basic Statistical Analysis (9th Edition), 9th ed; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Roy, W.; Merveille, J.-B.; Scheldeman, K.; Van Nieuwenhove, A.; Van Roozendael, B.; Schallier, R.; Maes, F. The Role of Belgian Airborne Sniffer Measurements in the MARPOL Annex VI Enforcement Chain. Atmosphere (Basel) 2023, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD STAT Https://Unctadstat.Unctad.Org/EN/Index.Html.

- Ship and Bunker Scrubber Equipped Tonnage Now 30% of Boxship Capacity.

- Winnes, H.; Fridell, E.; Moldanová, J. Effects of Marine Exhaust Gas Scrubbers on Gas and Particle Emissions. J Mar Sci Eng 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulière, V.; Baetens, K.; Lacroix, G. Potential Impact of Wash Water Effluents from Scrubbers on Water Acidification in the Southern North Sea; 2020.

- Teuchies, J.; Cox, T.J.S.; Van Itterbeeck, K.; Meysman, F.J.R.; Blust, R. The Impact of Scrubber Discharge on the Water Quality in Estuaries and Ports. Environ Sci Eur 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCIPPER SCIPPER Project Finds High Nitrogen Oxides Emissions of Tier III Vessels from Remote Measurements in North European Seas; 2023.

- Majamäki, E.; Jalkanen, J.-P. SCIPPER Project D4.2 Updated Inventories on Regional Shipping Activity and Port Regions; 2021.

- Jalkanen, J.-P.; Johansson, L.; Kukkonen, J.; Brink, A.; Kalli, J.; Stipa, T. Extension of an Assessment Model of Ship Traffic Exhaust Emissions for Particulate Matter and Carbon Monoxide. Atmos Chem Phys 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalkanen, J.-P.; Brink, A.; Kalli, J.; Pettersson, H.; Kukkonen, J.; Stipa, T. A Modelling System for the Exhaust Emissions of Marine Traffic and Its Application in the Baltic Sea Area. Atmos. Chem. Phys 2009, 9, 9209–9223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonson, J.E.; Jalkanen, J.P.; Johansson, L.; Gauss, M.; Denier van der Gon, H.A.C. Model Calculations of the Effects of Present and Future Emissions of Air Pollutants from Shipping in the Baltic Sea and the North Sea. Atmos Chem Phys 2015, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppälä, S.D.; Kuula, J.; Hyvärinen, A.-P.; Saarikoski, S.; Rönkkö, T.; Keskinen, J.; Jalkanen, J.-P.; Timonen, H. Effects of Marine Fuel Sulfur Restrictions on Particle Number Concentrations and Size Distributions in Ship Plumes in the Baltic Sea. Atmos Chem Phys 2021, 21, 3215–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Color flag | σ | U | CI | Sulfur limit | T | Tops | |||

| 2015-2019 | Yellow | 1 | 30% | 68% | 0.10% | 0.145% | 0.15% | ||

| Orange | 1.96 | 35% | 95% | 0.11% | 0.174% | 0.20% | |||

| Red | 2.576 | 43% | 99% | 0.15% | 0.275% | 0.40% | |||

| 2020-2022 | Yellow | 1 | 25% | 68% | 0.10% | 0.13% | 0.13% | ||

| Orange | 1.96 | 38% | 95% | 0.11% | 0.18% | 0.20% | |||

| Red | 2.576 | 48% | 99% | 0.15% | 0.29% | 0.30% | |||

| 2020-2022 (with n = 2) | Yellow | 1 | 18% | 68% | 0.10% | 0.12% | 0.12% | ||

| Orange | 1.96 | 27% | 95% | 0.11% | 0.15% | 0.15% | |||

| Red | 2.576 | 34% | 99% | 0.15% | 0.23% | 0.25% | |||

| Tier | LTier | Color flag | NTE | σ | U | T | Tops-20 | Tops-22 | |

| Tier I* | 17 | Yellow | 15% | 1 | 19.8% | 21.2 | 25 | 25 | |

| Orange | 20% | 1.96 | 44.5% | 31.8 | 35 | 35 | |||

| Red | 50% | 2.576 | 58.5% | 53.2 | 60 | 55 | |||

| Tier II | 14.4 | Yellow | 15% | 1 | 19.8% | 17.9 | 20 | 20 | |

| Orange | 20% | 1.96 | 44.5% | 26.9 | 30 | 30 | |||

| Red | 50% | 2.576 | 58.5% | 45.0 | 50 | 45 | |||

| Tier III | 3.4 | Yellow | 50% | 1 | 19.8% | 5.4 | 7 | 6 | |

| Orange | 60% | 1.96 | 44.5% | 7.5 | 9 | 8 | |||

| Red | 65% | 2.576 | 58.5% | 8.9 | 12 | 9 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).