Submitted:

18 April 2023

Posted:

19 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Solubility Test

2.3. Self-emulsification and Pseudoternary Phase diagram

2.4. Preparation of SMEDDS

2.5. Morphological analysis

2.6. Droplet size and zeta potential analysis

2.7. Stability test

2.8. In vitro dissolution test

2.9. In vivo pharmacokinetic study

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Solubility test of OLA

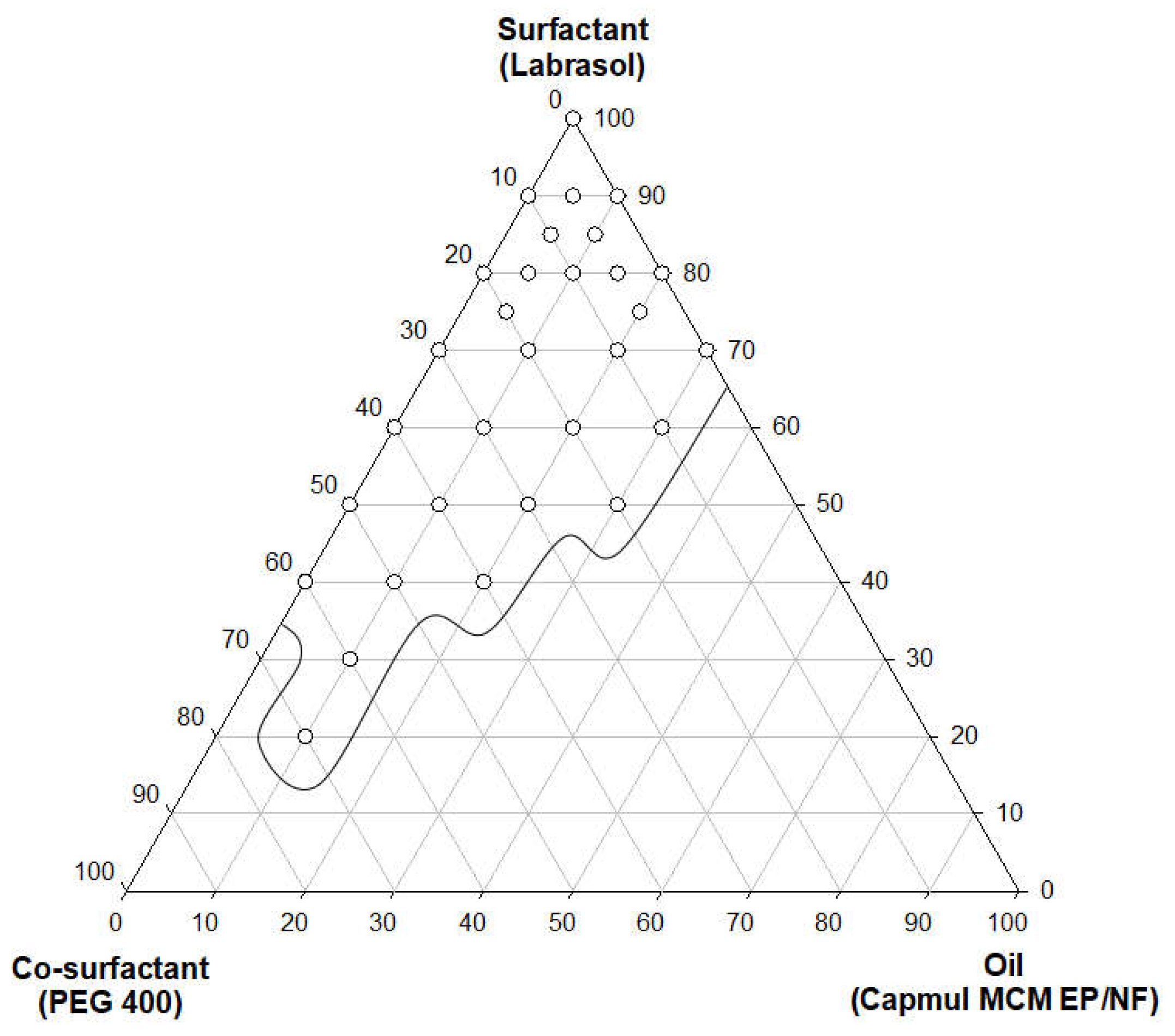

3.2. Construction of a pseudoternary phase diagram

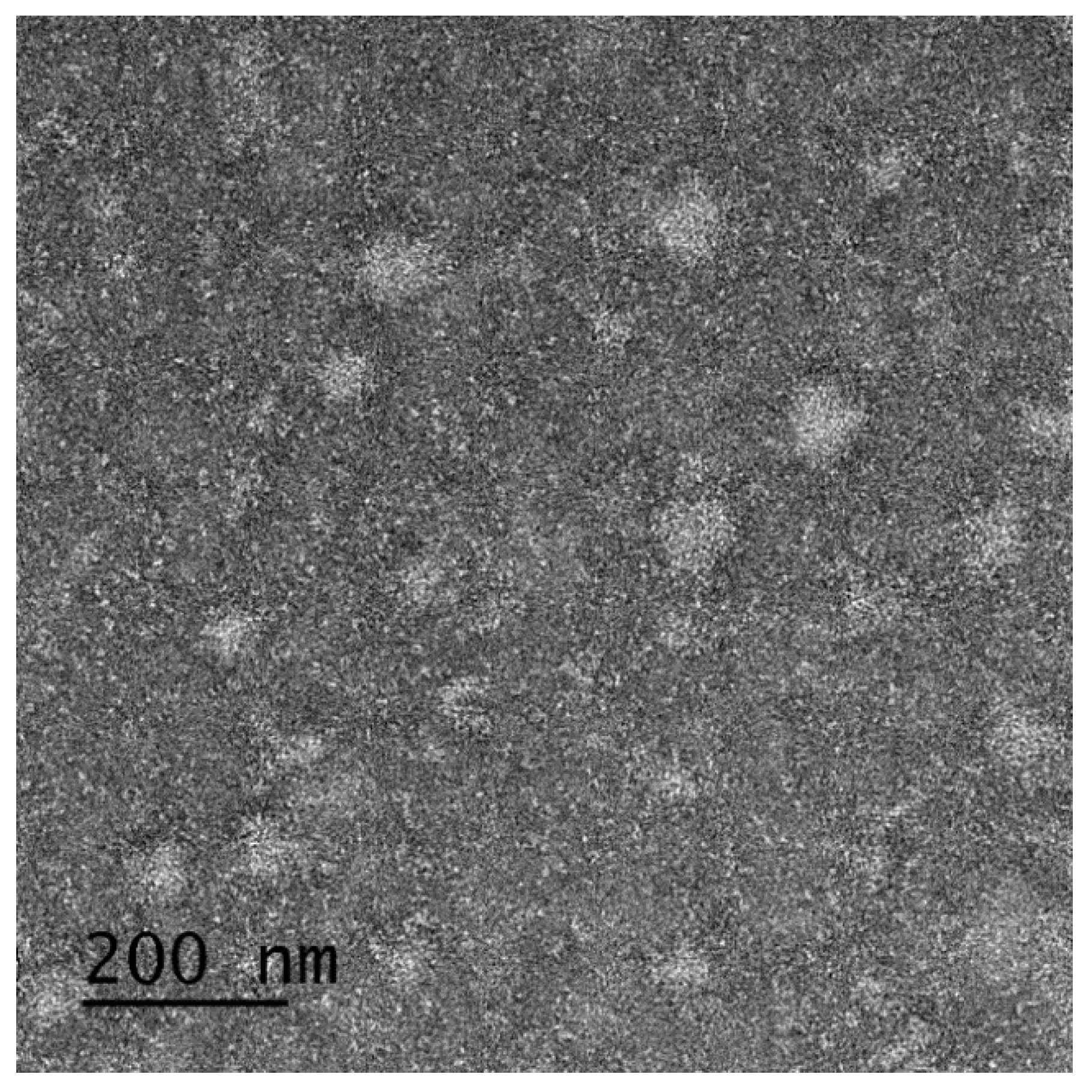

3.3. Characterization of SMEDDS

3.4. Stability study of SMEDDS

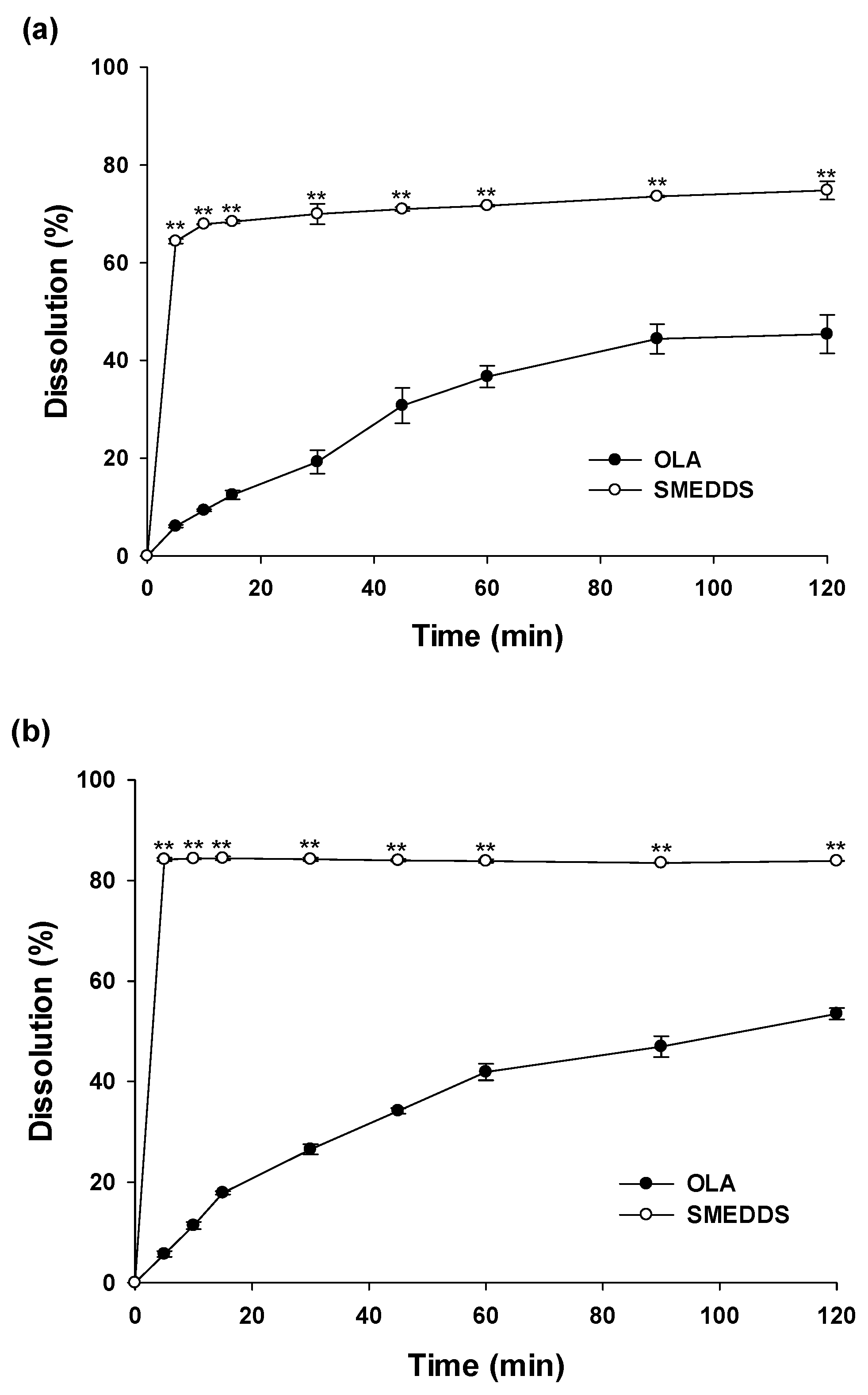

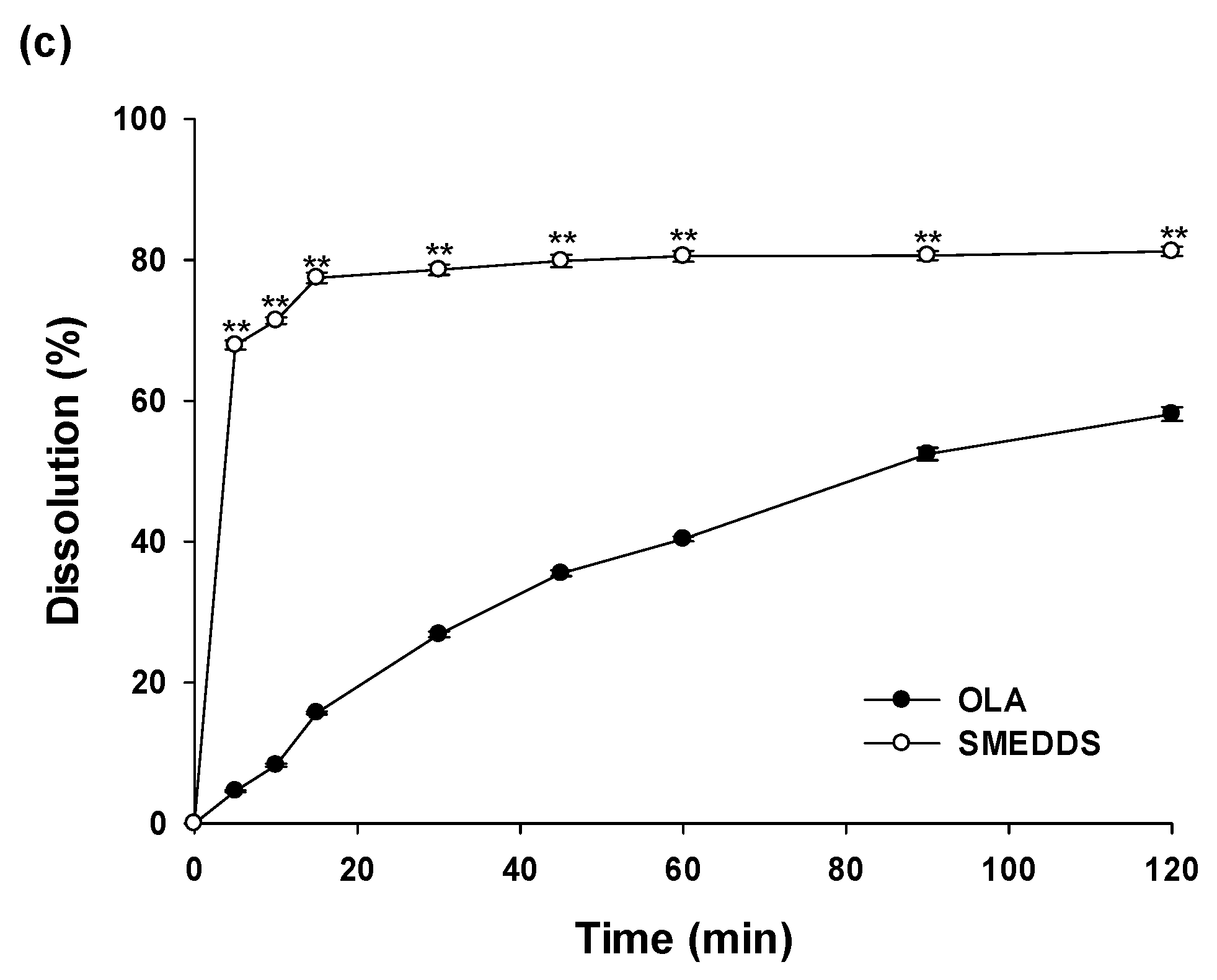

3.5. In vitro dissolution study

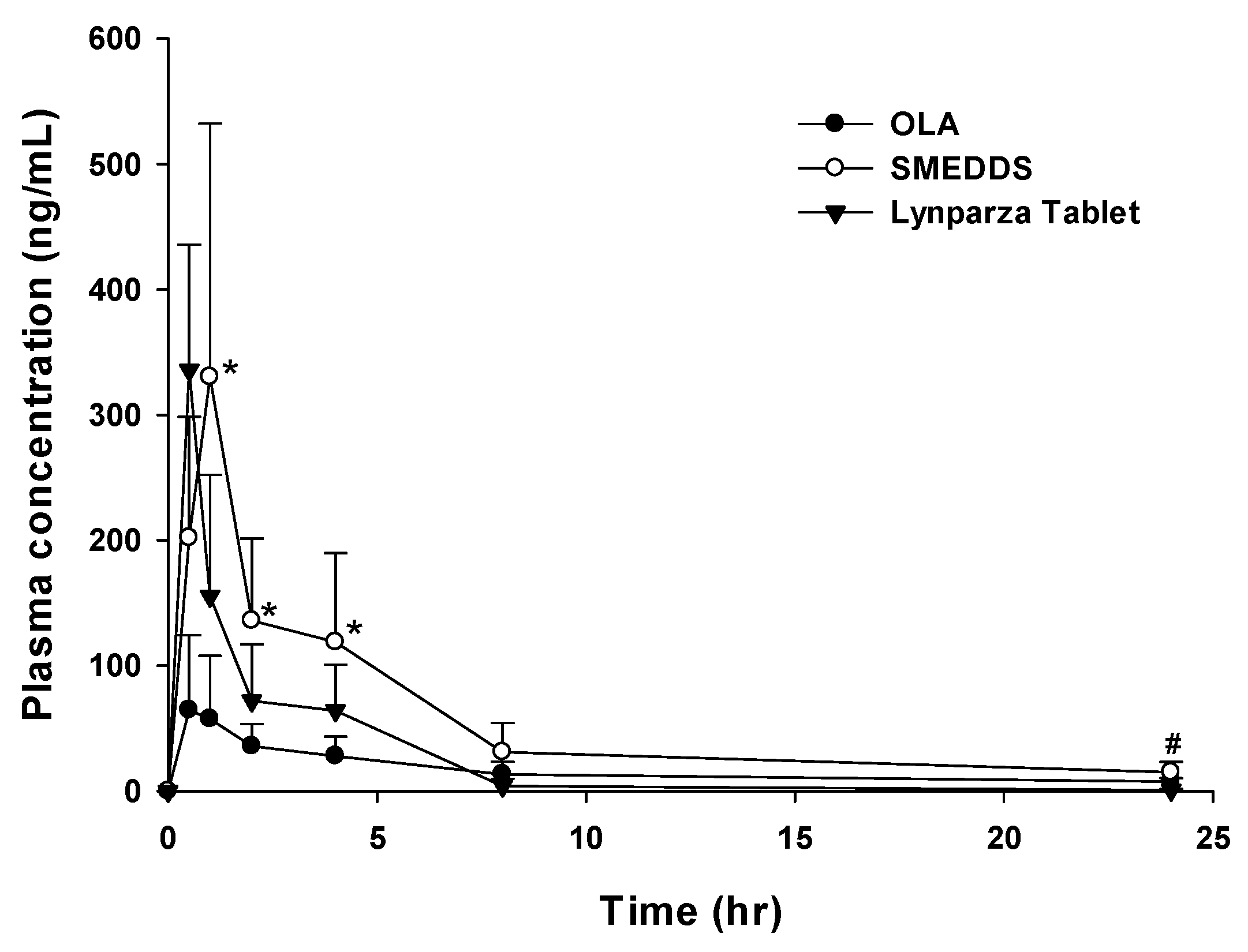

3.6. In vivo pharmacokinetic study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amidon, G. L. Lennernäs, H., Shah, V. P., & Crison, J. R. (1995). A theoretical basis for a biopharmaceutic drug classification: the correlation of in vitro drug product dissolution and in vivo bioavailability. Pharmaceutical research, 12(3), 413-420.

- Dahan, A.; Miller, J.M.; Amidon, G.L. Prediction of Solubility and Permeability Class Membership: Provisional BCS Classification of the World’s Top Oral Drugs. AAPS J. 2009, 11, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karashima, M.; Kimoto, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Kojima, T.; Ikeda, Y. A novel solubilization technique for poorly soluble drugs through the integration of nanocrystal and cocrystal technologies. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2016, 107, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.D.; Trevaskis, N.L.; Charman, S.A.; Shanker, R.M.; Charman, W.N.; Pouton, C.W.; Porter, C.J.H. Strategies to Address Low Drug Solubility in Discovery and Development. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65, 315–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadka, P.; Ro, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, I.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, H.; Cho, J.M.; Yun, G.; Lee, J. Pharmaceutical particle technologies: An approach to improve drug solubility, dissolution and bioavailability. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 9, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, Y.; Wada, K.; Nakatani, M.; Yamada, S.; Onoue, S. Formulation design for poorly water-soluble drugs based on biopharmaceutics classification system: Basic approaches and practical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 420, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, S.Y.K.; Ibisogly, A.; Bauer-Brandl, A. Solubility enhancement of BCS Class II drug by solid phospholipid dispersions: Spray drying versus freeze-drying. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 496, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savjani, K. T. , Gajjar, A. K., & Savjani, J. K. (2012). Drug solubility: importance and enhancement techniques. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, A. , Nagaich, U., Gulati, N., Sharma, V. K., Khosa, R. L., & Partapur, M. U. (2012). Enhancement of solubilization and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs by physical and chemical modifications: A recent review. J Adv Pharm Educ Res, 2(1), 32-67.

- Sikarra, D. , Shukla, V., Kharia, A. A., & Chatterjee, D. P. (2012). Techniques for solubility enhancement of poorly soluble drugs: an overview. JMPAS, 1, 1-22. 1.

- Singh, A.; Worku, Z.A.; Mooter, G.V.D.; Bpharm; Mpharm; D, P. Oral formulation strategies to improve solubility of poorly water-soluble drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2011, 8, 1361–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahr, A.; Liu, X.; D, P. Drug delivery strategies for poorly water-soluble drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2007, 4, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Holm, R.; Müllertz, A. Lipid-based formulations for oral administration of poorly water-soluble drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 453, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannin, V.; Chevrier, S.; Michenaud, M.; Dumont, C.; Belotti, S.; Chavant, Y.; Demarne, F. Development of self emulsifying lipid formulations of BCS class II drugs with low to medium lipophilicity. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 495, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalepu, S. , Manthina, M., & Padavala, V. (2013). Oral lipid-based drug delivery systems–an overview. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 3(6), 361-372.

- Humberstone, A.J.; Charman, W.N. Lipid-based vehicles for the oral delivery of poorly water soluble drugs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1997, 25, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göke, K.; Lorenz, T.; Repanas, A.; Schneider, F.; Steiner, D.; Baumann, K.; Bunjes, H.; Dietzel, A.; Finke, J.H.; Glasmacher, B.; et al. Novel strategies for the formulation and processing of poorly water-soluble drugs. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2018, 126, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J. Liposomal formulations for enhanced lymphatic drug delivery. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 8, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Sawant, K.K. Self Micro-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System: Formulation Development and Biopharmaceutical Evaluation of Lipophilic Drugs. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2009, 6, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouton, C.W. Lipid formulations for oral administration of drugs: non-emulsifying, self-emulsifying and ‘self-microemulsifying’ drug delivery systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000, 11, S93–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, F.; Jannin, V.; Chevrier, S.; Boulghobra, H.; Hristov, D.R.; Ritter, N.; Miolane, C.; Chavant, Y.; Demarne, F.; Brayden, D.J. Labrasol® is an efficacious intestinal permeation enhancer across rat intestine: Ex vivo and in vivo rat studies. J. Control. Release 2019, 310, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukozturk, F.; Benneyan, J.C.; Carrier, R.L. Impact of emulsion-based drug delivery systems on intestinal permeability and drug release kinetics. J. Control. Release 2010, 142, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokania, S.; Joshi, A.K. Self-microemulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS) – challenges and road ahead. Drug Deliv. 2014, 22, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.S.; Gurram, A.; Deshpande, P.; Kar, S.; Nayak, U.; Udupa, N. Role of components in the formation of self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 77, 249–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyatanwar, A. U. , Jadhav, K. R., & Kadam, V. J. (2010). Self micro-emulsifying drug delivery system (SMEDDS). Journal of Pharmacy Research, 3(2), 75-83.

- Narang, A.S.; Delmarre, D.; Gao, D. Stable drug encapsulation in micelles and microemulsions. Int. J. Pharm. 2007, 345, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Dong, B.; Qin, S.; Chu, Q.; Wu, K.; Luo, S. Advances and perspectives of PARP inhibitors. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, M.K.; Chen, A.P. PARP Inhibitor Treatment in Ovarian and Breast Cancer. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2011, 35, 7–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D.L. Patent Review of Manufacturing Routes to Recently Approved PARP Inhibitors: Olaparib, Rucaparib, and Niraparib. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 2017, 21, 1227–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathade, A.D.; Kommineni, N.; Bulbake, U.; Thummar, M.M.; Samanthula, G.; Khan, W. Preparation and Comparison of Oral Bioavailability for Different Nano-formulations of Olaparib. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedlander, M.; Banerjee, S.; Mileshkin, L.; Scott, C.; Shannon, C.; Goh, J. Practical guidance on the use of olaparib capsules as maintenance therapy for women with BRCA mutations and platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Asia-Pacific J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 12, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Li, J.; Bui, K.; Learoyd, M.; Berges, A.; Milenkova, T.; Al-Huniti, N.; Tomkinson, H.; Xu, H. Bridging Olaparib Capsule and Tablet Formulations Using Population Pharmacokinetic Meta-analysis in Oncology Patients. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 58, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledermann, J.; Harter, P.; Gourley, C.; Friedlander, M.; Vergote, I.; Rustin, G.; Scott, C.; Meier, W.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Safra, T.; et al. Olaparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive Relapsed Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 1382–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadi, R.; Dand, N. BCS class IV drugs: Highly notorious candidates for formulation development. J. Control. Release 2017, 248, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Chaurasiya, A.; Singh, M.; Upadhyay, S.C.; Mukherjee, R.; Khar, R.K. Exemestane Loaded Self-Microemulsifying Drug Delivery System (SMEDDS): Development and Optimization. Aaps Pharmscitech 2008, 9, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, X.; Fahr, A. Skin penetration and deposition of carboxyfluorescein and temoporfin from different lipid vesicular systems: In vitro study with finite and infinite dosage application. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 408, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Firempong, C.K.; Zhu, Y.; Omari-Siaw, E.; Zheng, Y.; Pu, Z.; Xu, X.; Yu, J. Enhanced oral bioavailability of [6]-Gingerol-SMEDDS: Preparation, in vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 27, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powis, G. Dose-Dependent Metabolism, Therapeutic Effect, and Toxicity of Anticancer Drugs in Man. Drug Metab. Rev. 1983, 14, 1145–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, J.; Moreno, V.; Gupta, A.; Kaye, S.B.; Dean, E.; Middleton, M.R.; Friedlander, M.; Gourley, C.; Plummer, R.; Rustin, G.; et al. An Adaptive Study to Determine the Optimal Dose of the Tablet Formulation of the PARP Inhibitor Olaparib. Target. Oncol. 2016, 11, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Vehicle | Solubility (mg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Aqueous solution | |

| Distilled Water | 0.07 ± 0.25 |

| pH 1.2 | 0.06 ± 0.57 |

| pH 6.8 | 0.06 ± 0.42 |

| Oils | |

| Capmul MCM EP/NF | 41.68 ± 0.02 |

| Cotton Seed Oil | 0.06 ± 0.20 |

| Labrafil M 1944 CS | 0.95 ± 0.71 |

| Labrafac PG | 0.13 ± 0.10 |

| Oleic acid | 3.83 ± 0.22 |

| Surfactants and co-surfactants | |

| Kolliphor EL | 7.83 ± 6.06 |

| Tween 80 | 8.82 ± 0.28 |

| Span 80 | 4.82 ± 3.52 |

| Labrasol | 36.60 ± 0.07 |

| Transcutol HP | 19.69 ± 0.14 |

| Plurol Oleique CC 497 | 4.99 ± 0.09 |

| Isopropyl Myristate | 0.04 ± 0.02 |

| PEG 400 | 47.66 ± 0.38 |

| Time (month) | Droplet size (nm) | Zeta potential (mV) | Drug content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) 25 °C, 60% RH | |||

| 0 | 141.1 ± 0.24 | -15.83 ± 1.09 | 101.05 ± 0.45 |

| 1 | 142.7 ± 0.39 | -18.75 ± 0.43 | 101.09 ± 0.17 |

| 3 | 164.1 ± 0.33 | -16.31 ± 0.65 | 101.01 ± 0.24 |

| (b) 40 °C, 75% RH | |||

| 0 | 141.1 ± 0.24 | -15.83 ± 1.09 | 101. 05 ± 0.45 |

| 1 | 143.0 ± 0.70 | -13.45 ± 0.82 | 99.02 ± 0.14 |

| 3 | 166.1 ± 2.69 | -15.99 ± 0.65 | 98.50 ± 0.15 |

| PK Parameters | OLA | Lynparza® tablet | SMEDDS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax(hr) | 0.8 | ± | 0.3 | 0.5 | ± | 0.0 | 0.9 | ± | 0.2# |

| Cmax(ng/mL) | 83.1 | ± | 49.6 | 335.7 | ± | 100.2 | 351.2 | ± | 173.3* |

| T1/2(hr) | 9.4 | ± | 0.1 | 4.0 | ± | 0.9 | 7.3 | ± | 3.2 |

| AUClast(ng·hr/mL) | 384.1 | ± | 136.2 | 518.2 | ± | 154.9 | 1242.7 | ± | 420.3**,# |

| AUCinf(ng·hr/mL) | 634.0 | ± | 437.2 | 522.0 | ± | 155.9 | 1427.3 | ± | 460.3*,# |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).