Submitted:

28 March 2023

Posted:

28 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

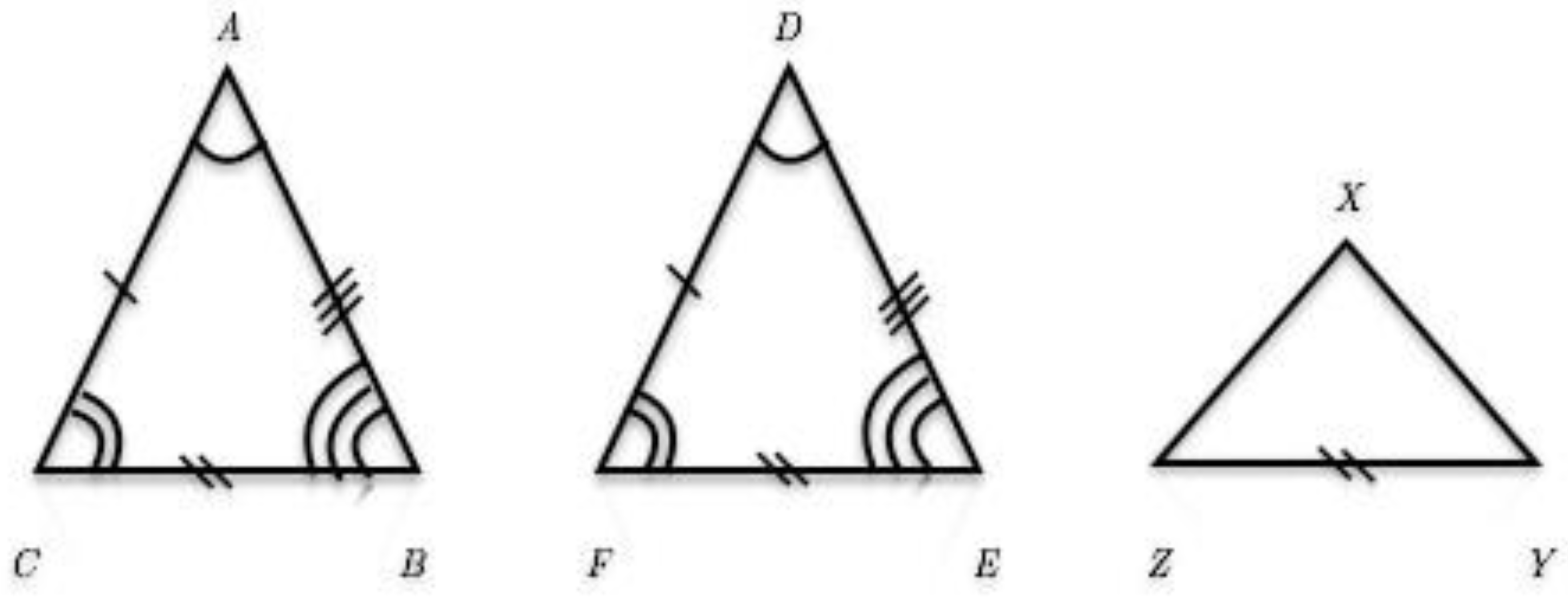

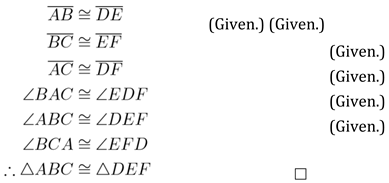

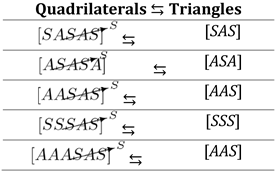

1. Introduction with Triangles

- Here:

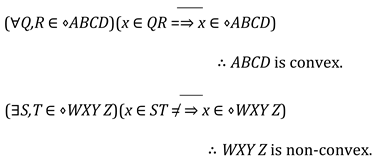

2. The Problem

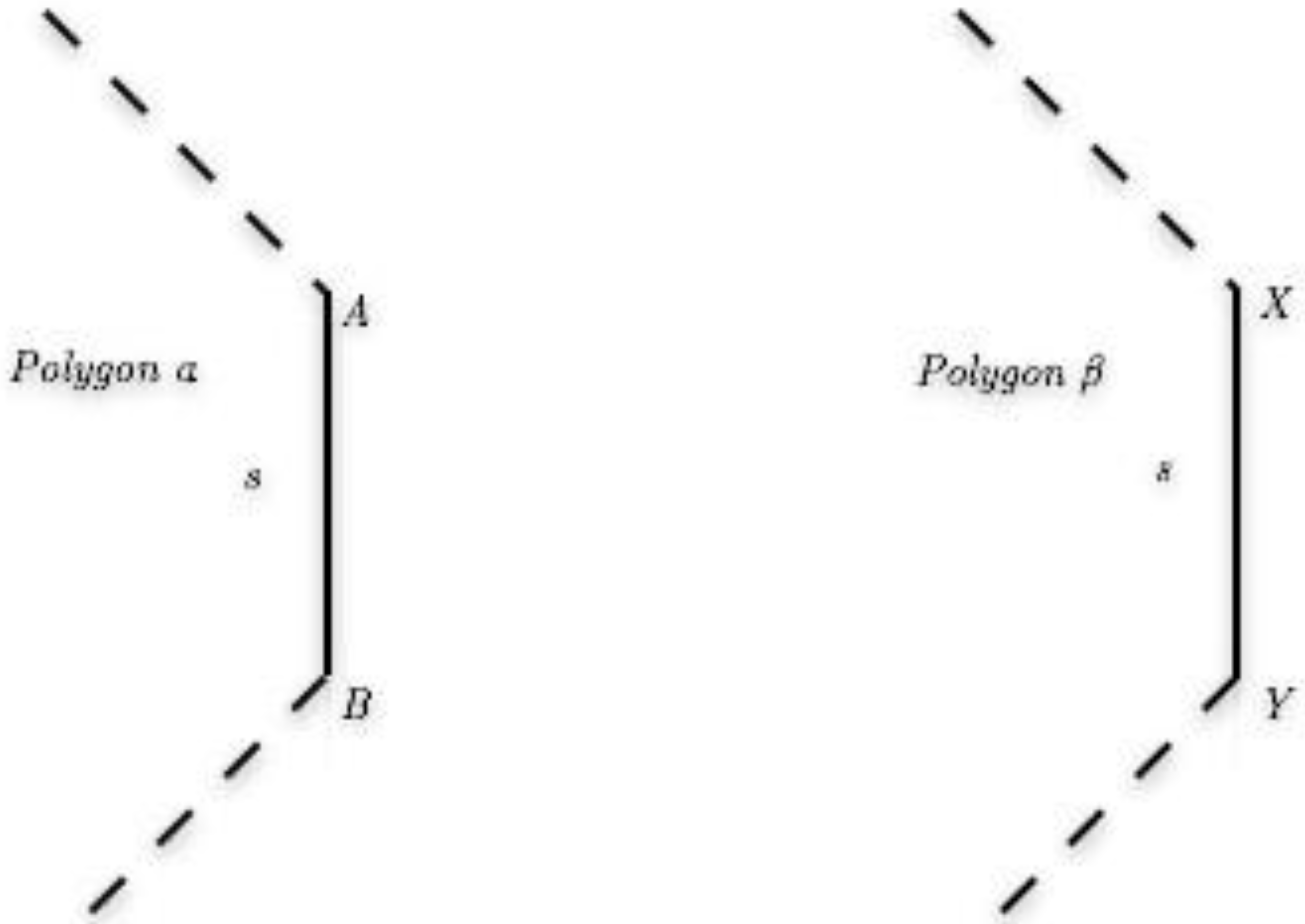

3. The Hypothesis

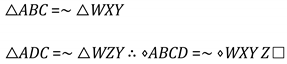

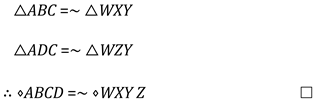

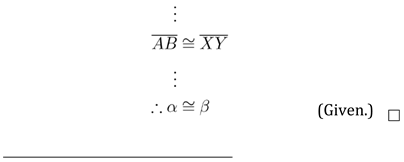

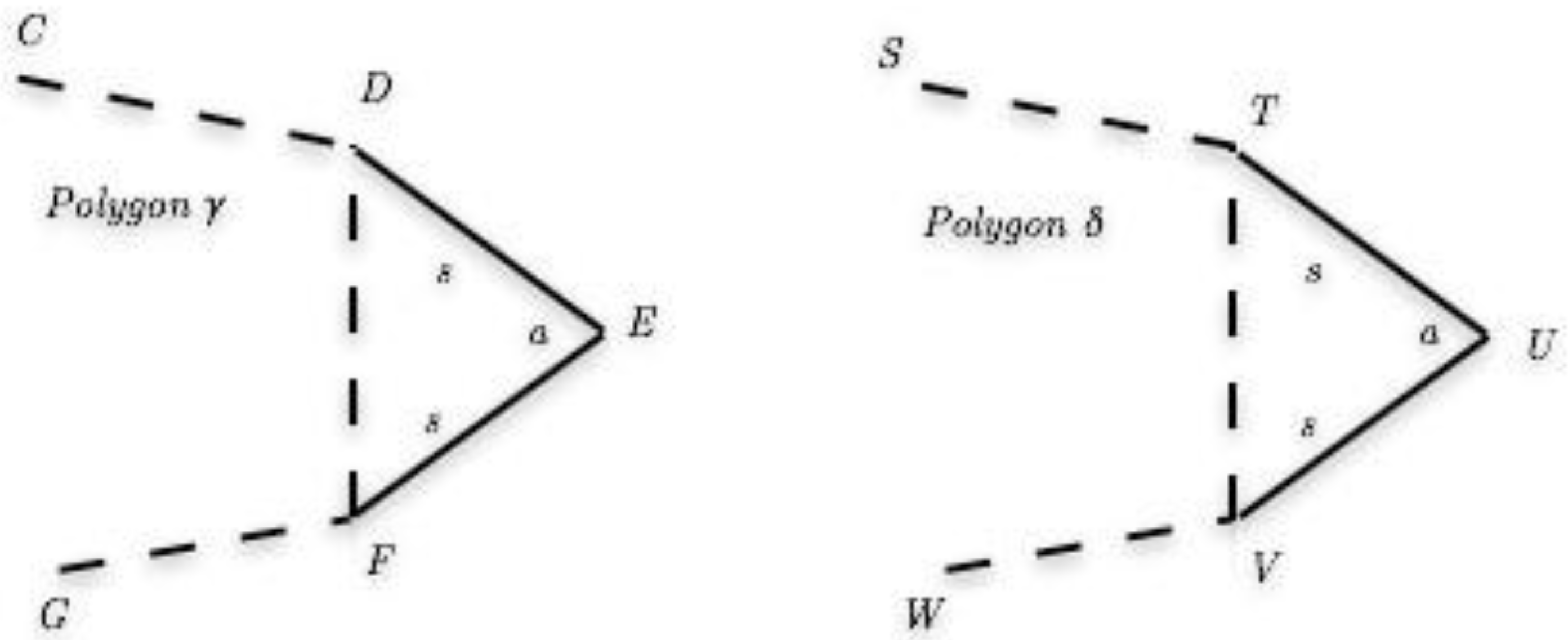

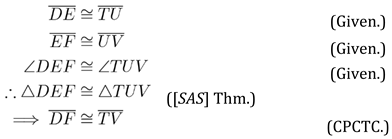

4. Proof

4.1. Hypothesis

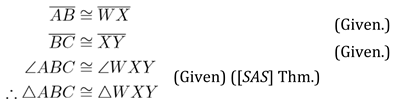

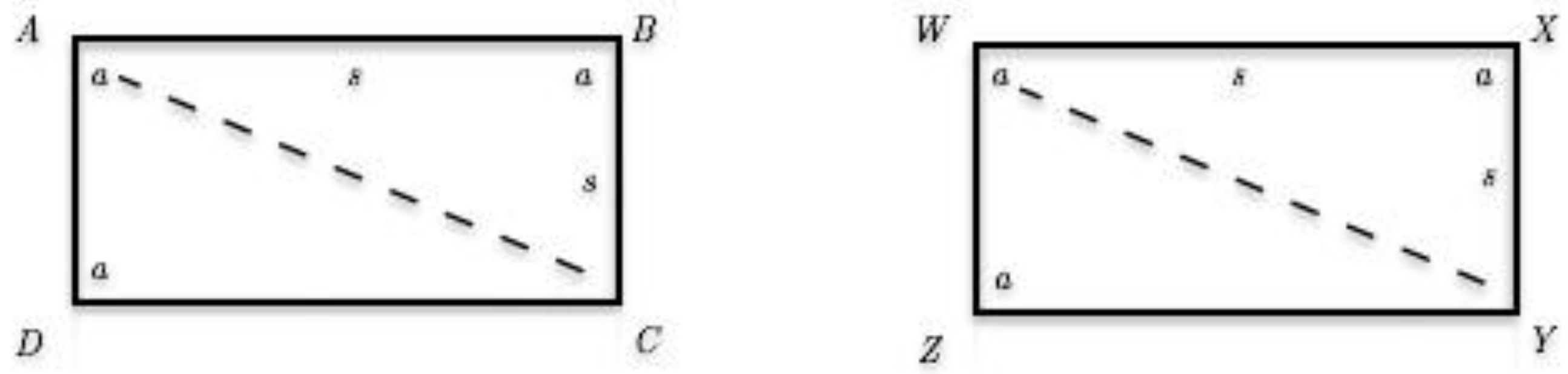

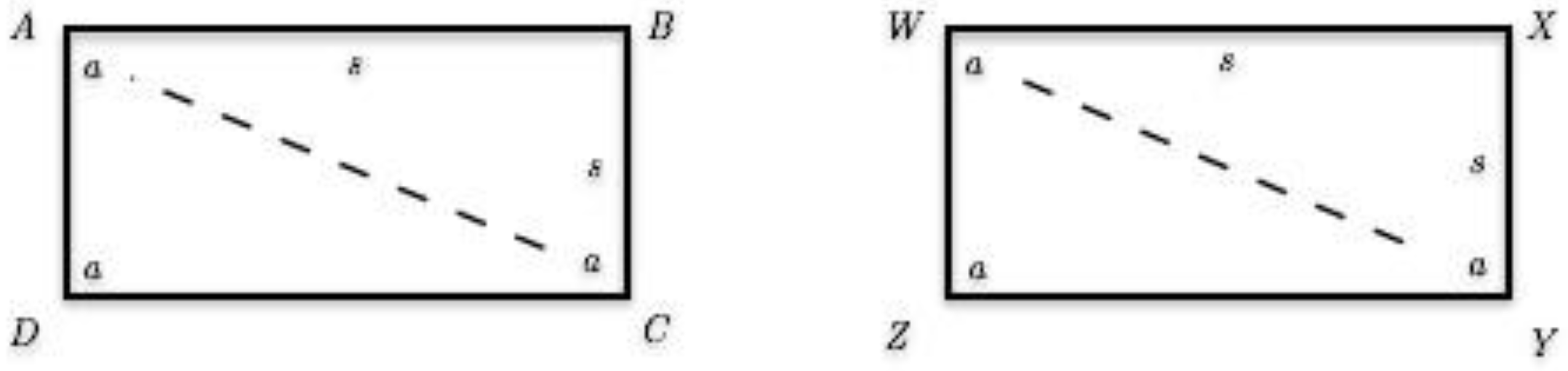

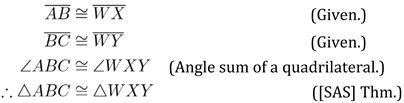

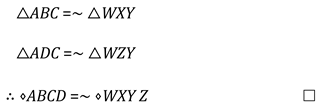

4.2. Base Case

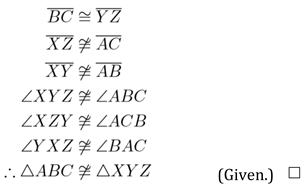

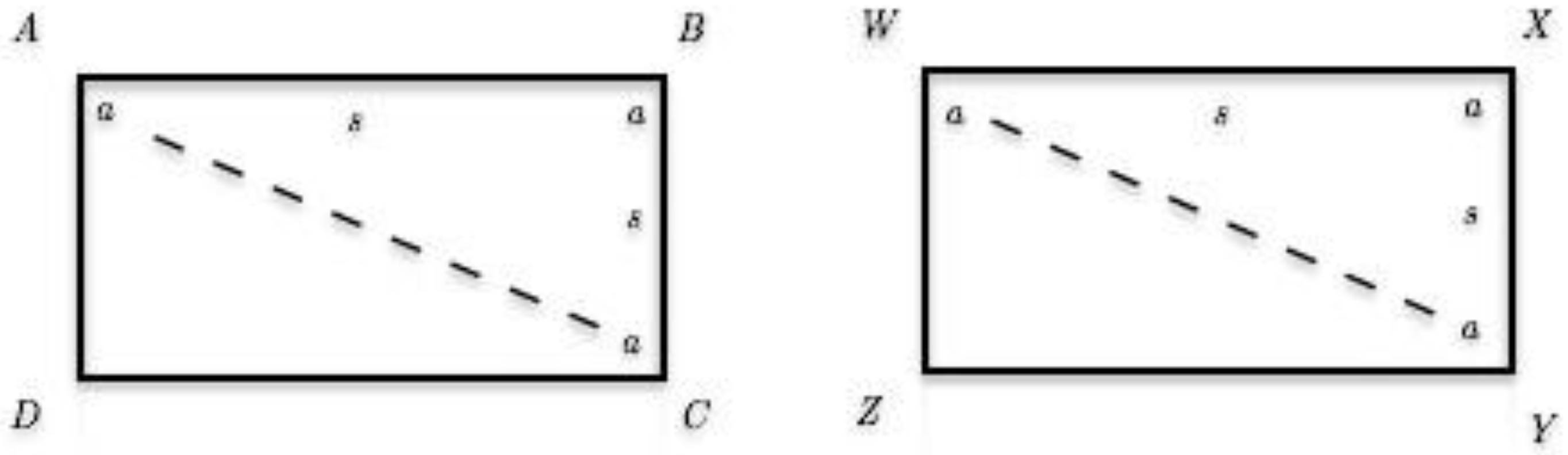

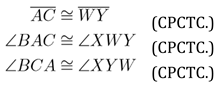

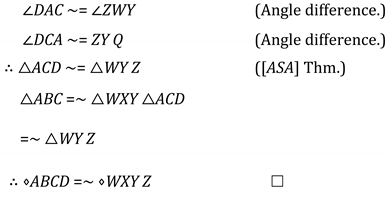

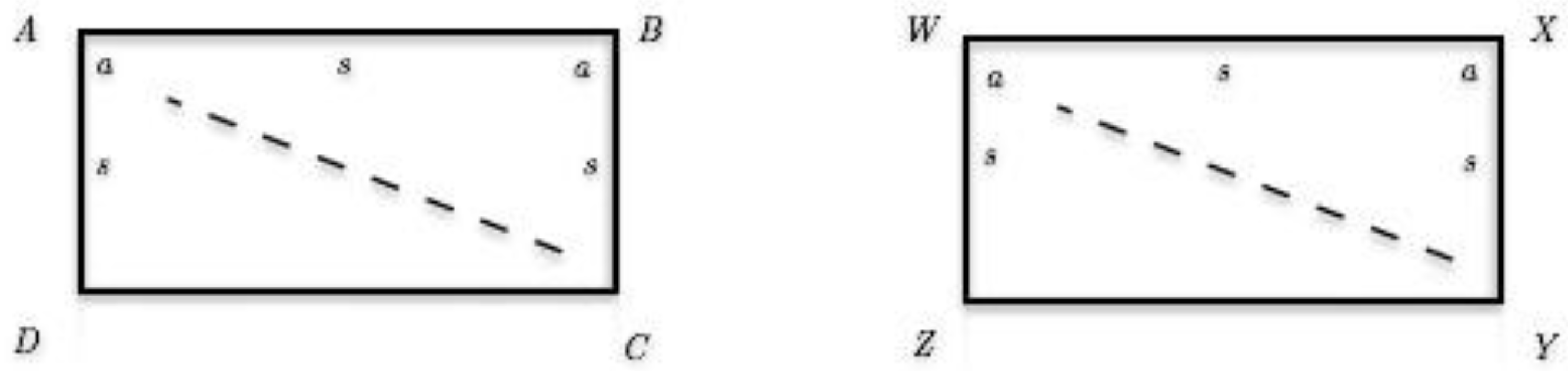

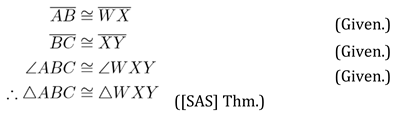

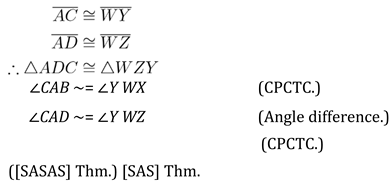

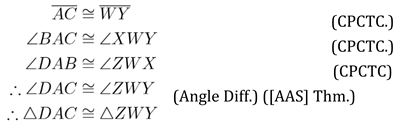

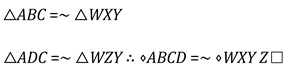

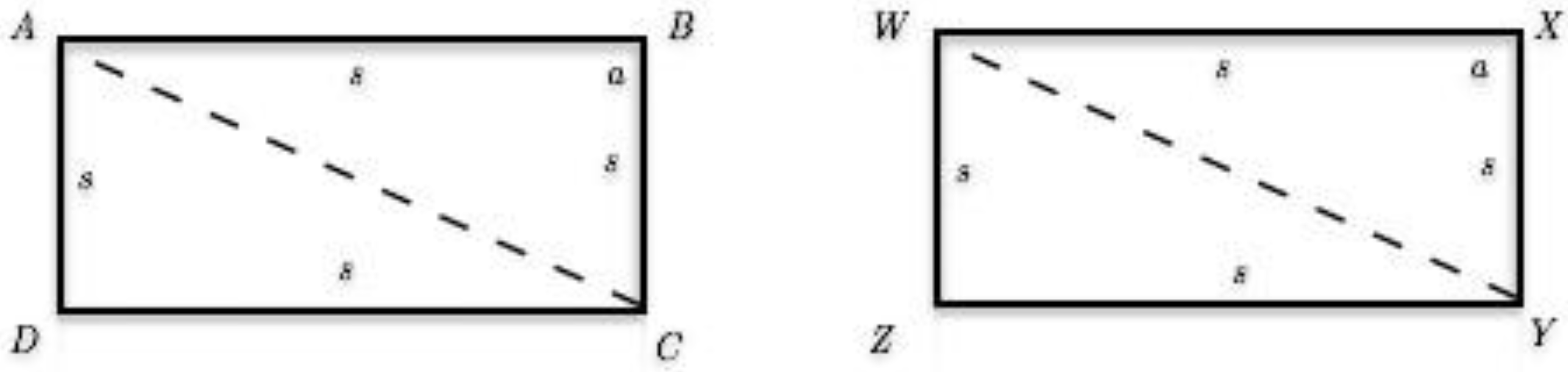

4.2.1. Proving [ASASA]

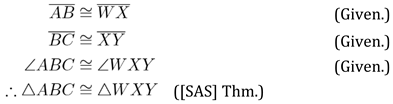

| ∠DAB ∼= ZWX | ([ASASA] Thm.) |

| ∠DCB ∼= ZY X | ([ASASA] Thm.) |

4.2.2. Proving [SASAS]

4.2.3. Proving [AASAS]

4.2.4. Proving [SSSSA]

4.2.5. Proving [AAASS]

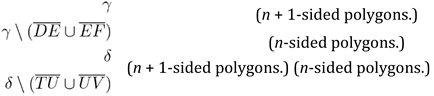

4.3. Inductive Step

this will come in use when we do a case-by-case analysis later.

this will come in use when we do a case-by-case analysis later.

if ai (from α and β) is A then bi is also A and if ai (from.

if ai (from α and β) is A then bi is also A and if ai (from.

if ai (from α and β) is A then bi is also A and if ai (from.

if ai (from α and β) is A then bi is also A and if ai (from.

4.4. Cases

- [b1,b2,b3 ···ASAS ···bk−2,bk−1,bk].

- [b1,b2,b3 ···SSAS ···bk−2,bk−1,bk].

- [b1,b2,b3 ···ASASA···bk−2,bk−1,bk].

- [b1,b2,b3 ···SSASS ···bk−2,bk−1,bk].

- [b1,b2,b3 ···SSASA···bk−2,bk−1,bk]

- Case 1: Case of [b1,b2,b3 ···ASAS ···bk−2,bk−1,bk]:

- Case 2: Case of [b1,b2,b3 ···SSAS ···bk−2,bk−1,bk]:

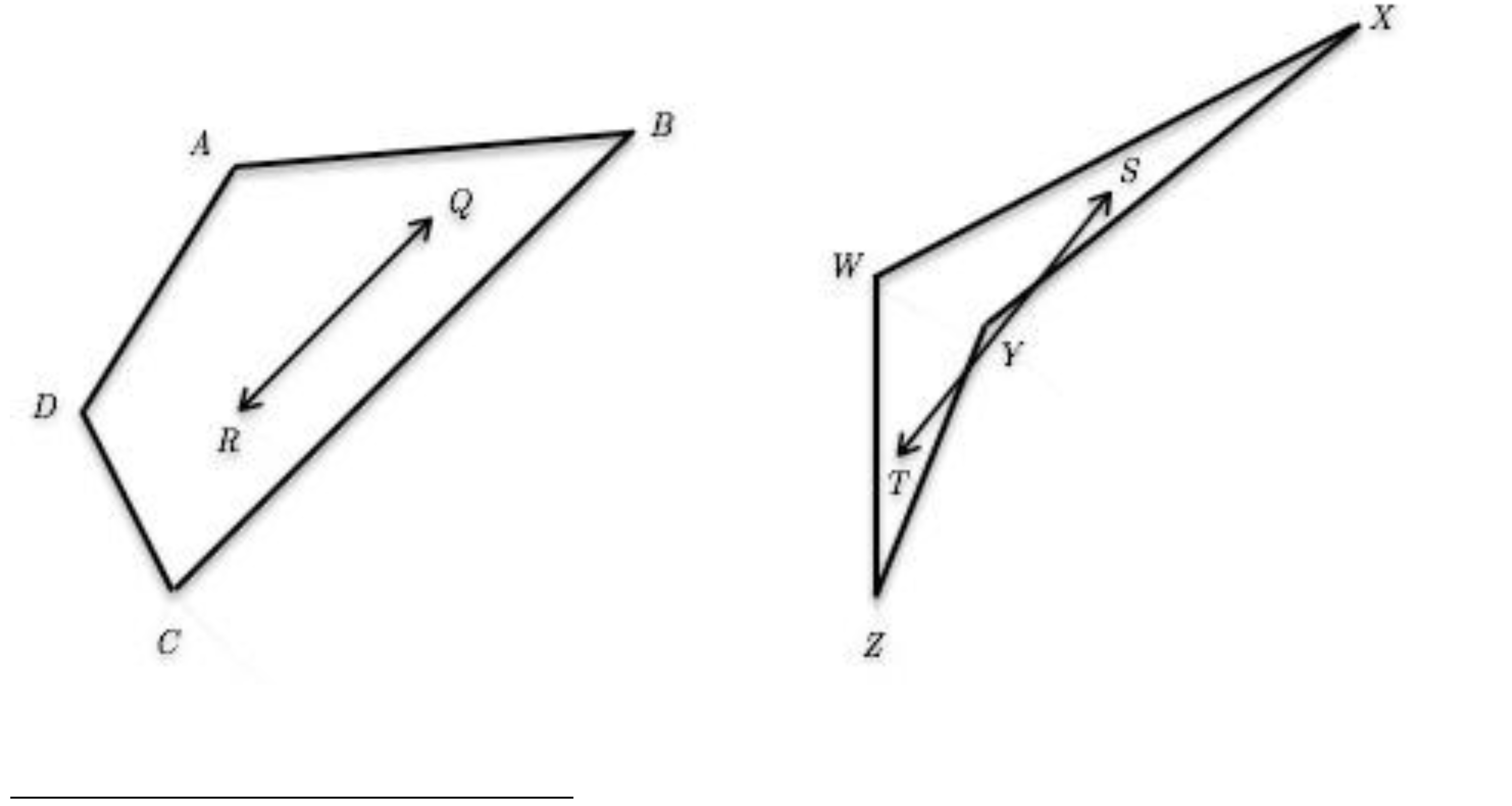

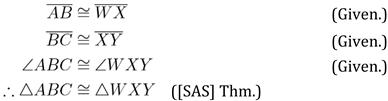

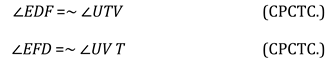

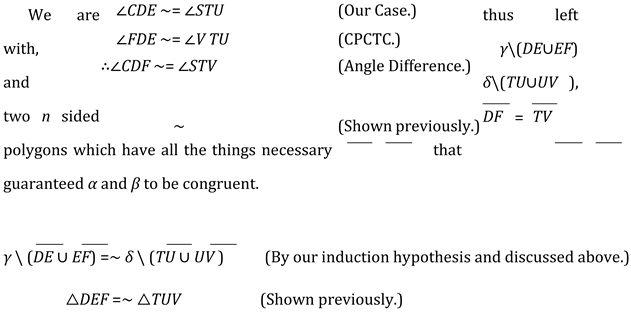

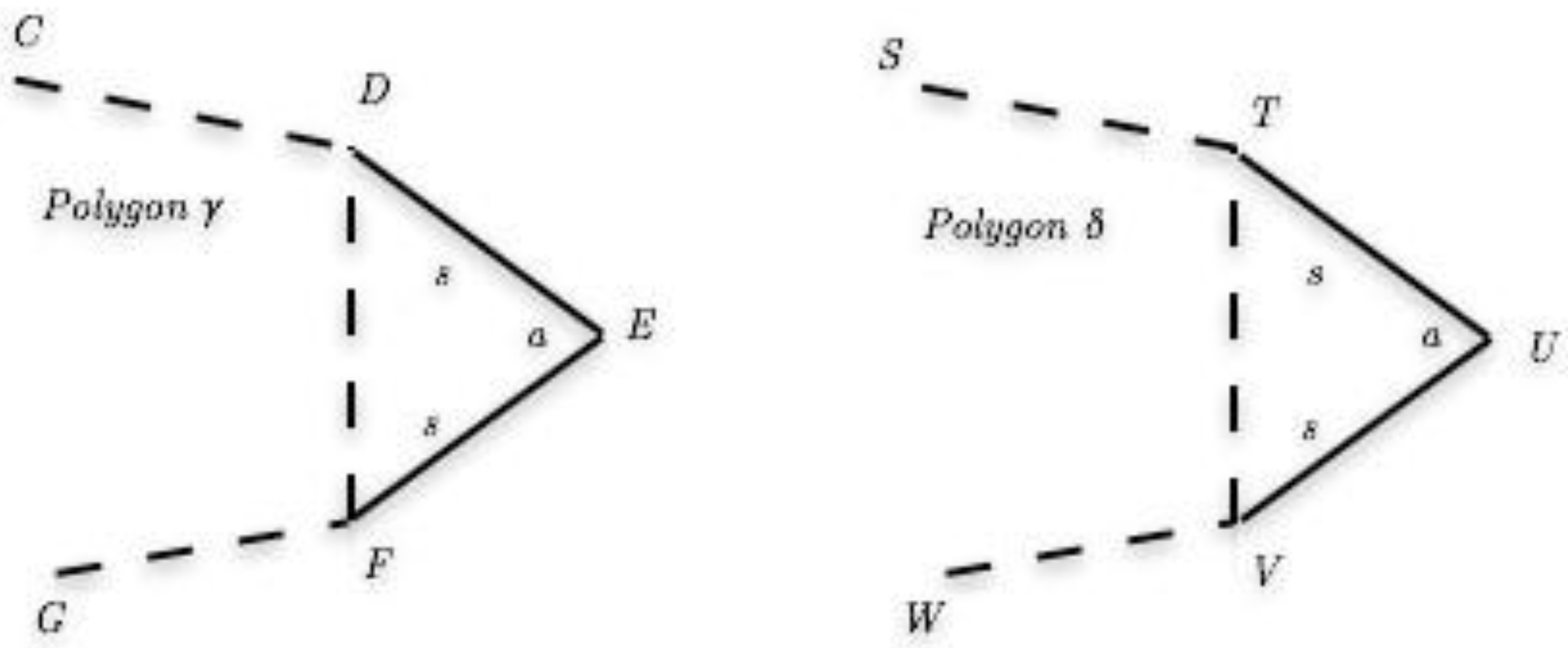

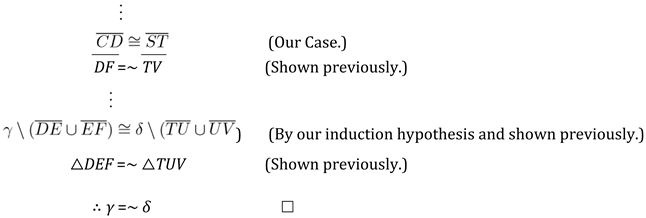

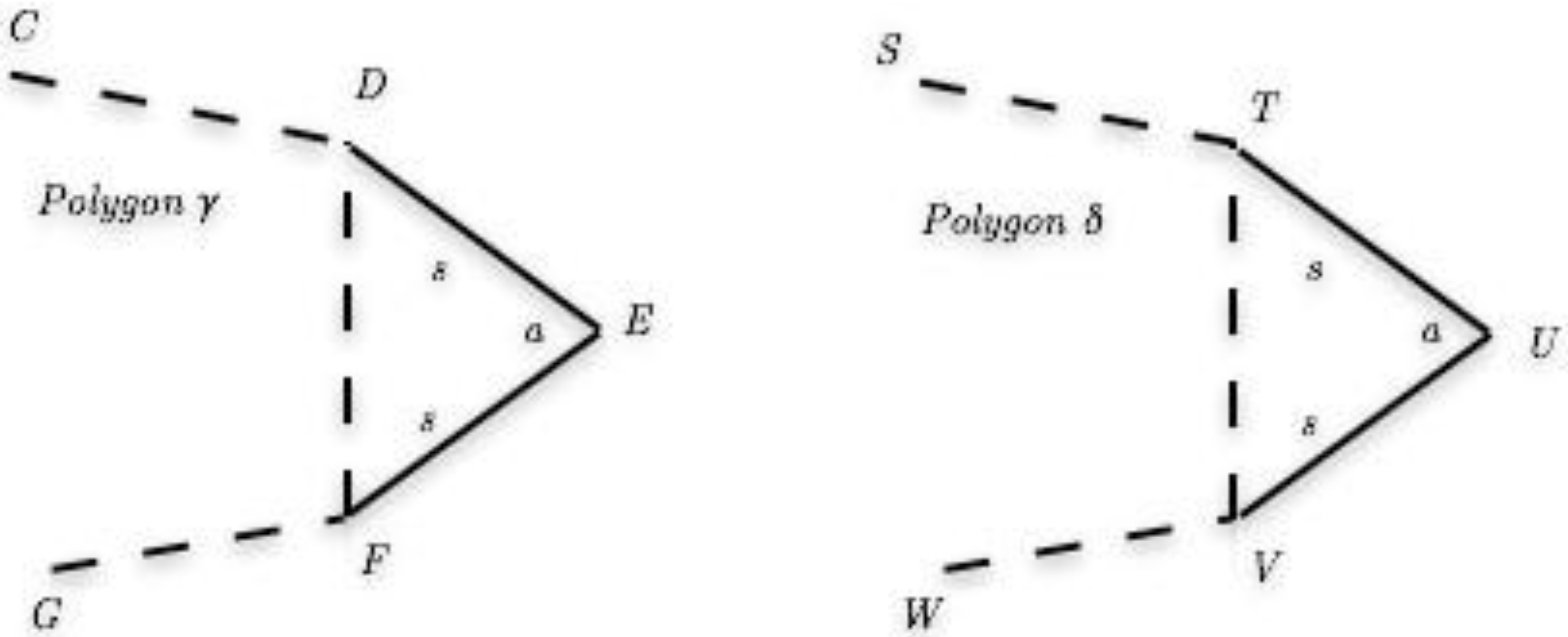

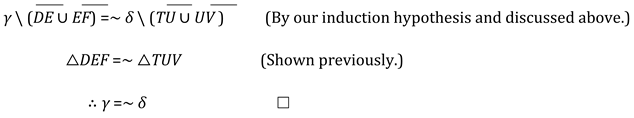

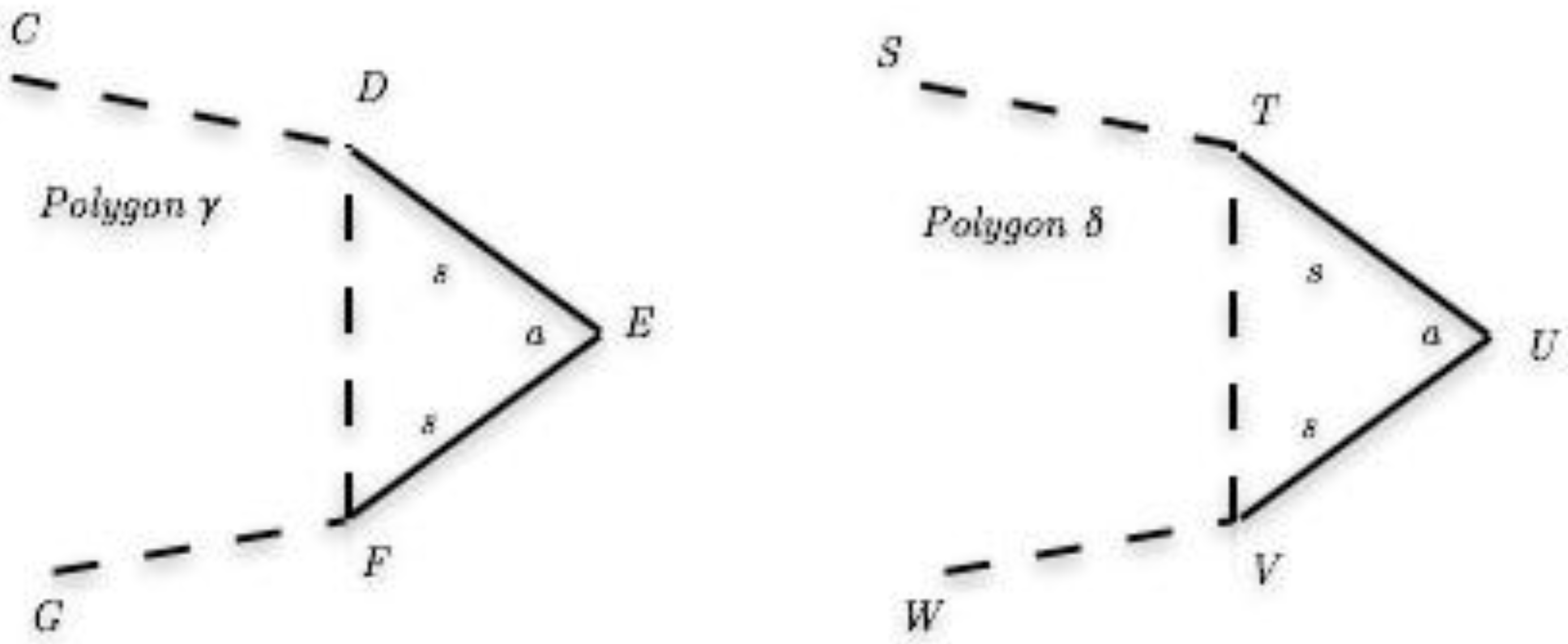

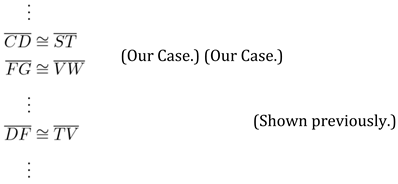

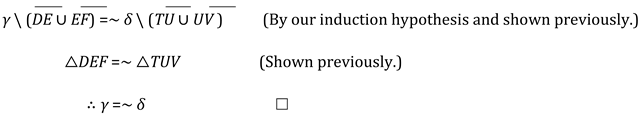

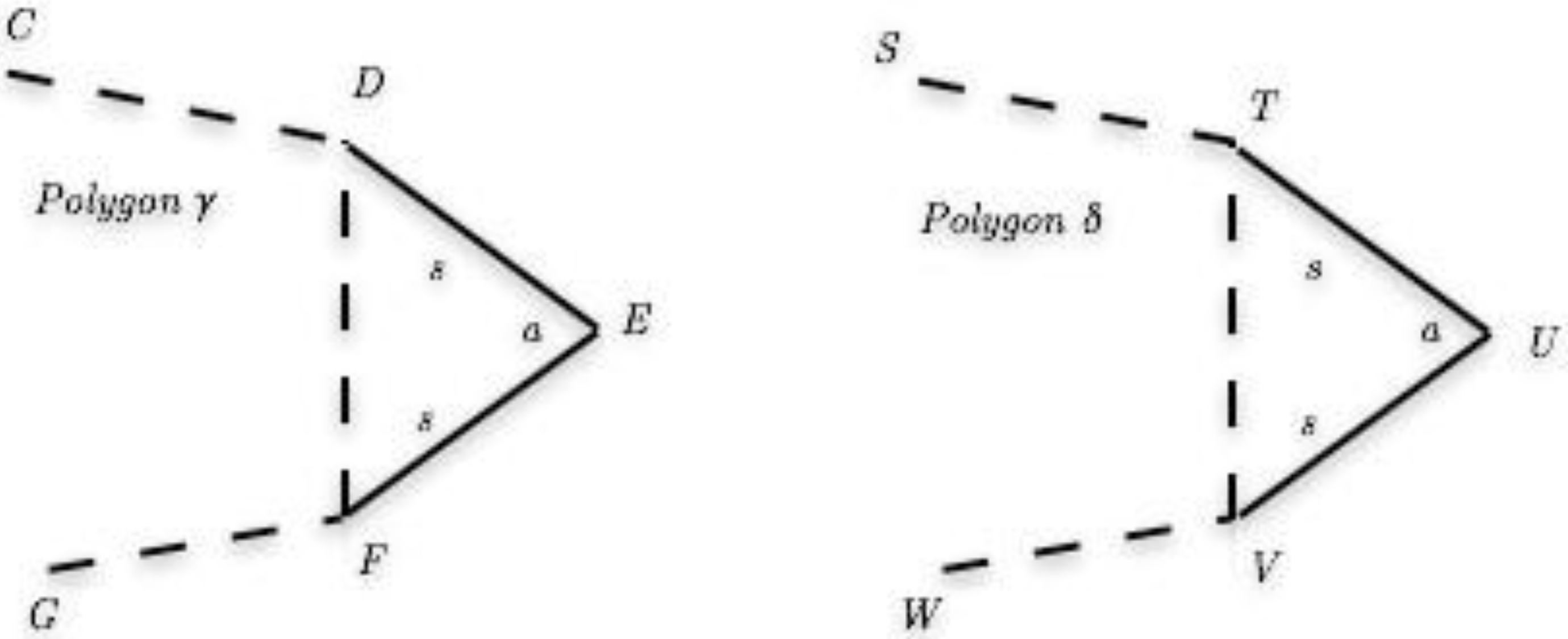

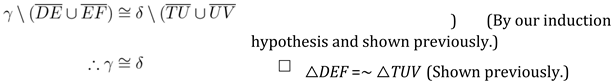

- Case 3: Case of [b1,b2,b3 ···ASASA···bk−2,bk−1,bk]:

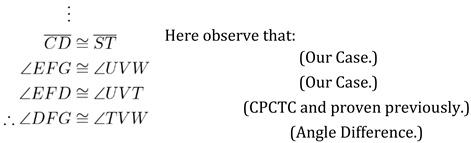

| ∠CDE ∼= ∠STU | (Our case.) |

| ∠EFT ∼= ∠UV W | (Our case.) |

| ∠FDE ∼= ∠V TU | (CPCTC.) |

| ∴∠FDC ∼= ∠V TS | (Angle Difference.) |

| ∠DFE ∼= ∠TV U | (CPCTC.) |

| ∴∠DFC ∼= ∠TV W | (CPCTC.) |

- Case 4: Case of [b1,b2,b3 ···SSASS ···bk−2,bk−1,bk]:

- Case 5: Case of [b1,b2,b3 ···SSASA···bk−2,bk−1,bk]:

4.5. Corollary

5. Conclusion

References

- Kay, David C, College Geometry: A Discovery Approach. pg. 132. HarperCollins College Puglishers, 1994.

- Kay, David C, College Geometry: A Discovery Approach. pg. 135. HarperCollins College Puglishers, 1994.

- University of Virginia’s College at Wise, 12. Six Easy Pieces: Quadrilateral Congruence Theorems. Mar, 2014. Available online: http://www.mcs.uvawise.edu/msh3e/ resources/geometryBook/12Quadrilaterals.pdf.

- Weisstein, Eric W, Convex Polygon – Wolfram MathWorld. Mar, 2014. Available online: http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ConvexPolygon.html.

| 1 | All congruence criteria are denoted within square brackets (e.g. [SAS]). This is a stylistic choice is intended to aid in clarity throughout the text. Sides and angles are also represented within square brackets (e.g. [S] and [A]) |

| 2 | Notice that between α and β, we have not only the letters in common, but also the values that the letters represent. But between the pairs α,β and γ,δ, only the letters are common. Imagine for example two pairs of triangles. The first pair is common by [SAS] as is the second pair. The first pair has two sides and an angle in common, the values of which are also equal. Between the two pairs, only the letters are common. It may be the case that between the pairs, no side or no angle whatsoever are equal. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).