1. Introduction

The ectoparasitosis tungiasis occurs in resource-poor communities in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and several Caribbean islands. Despite recent recognition as a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) by the World Health Organization (WHO), its inclusion in the WHO’s NTD road map (2021-2030), and its widespread occurrence, systematic data on the occurrence of disease and severe disease are still scarce [

1,

2]. A recent study based on ecological niche modeling estimated that a total of 450 million people are living in areas of risk for tungiasis, in 17 Latin American countries, but this study is based on limited published data, spanning several decades [

3].

There are only few population-based studies from Brazil, indicating that tungiasis is a severe problem in human and animal populations in several settings [

1,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Thus, there is a dire need for data on the distribution of tungiasis in possibly endemic regions.

As a first step to fill this gap, a rapid assessment method – based on the visual inspection of the periungual region of the feet - has been developed and validated in Brazil and Nigeria [

8]. This approach requires field visits and quick inspection of individuals. In settings with very limited resources and a wide geographic range, this may be a challenge. Obtaining information from key informants and health care networks may thus be a more cost-effective and quicker approach to estimate general disease occurrence and severity on the municipality level.

In 2021, a WHO informal expert meeting to develop a conceptual framework for tungiasis raised awareness that the information status on disease mapping, surveillance, prevention and treatment is “

desperate” [

9]. The same informal WHO meeting concluded that research priorities should include i.a. mapping “

the spatial distribution and dimensions of human and animal tungiasis at district and country levels”.

In line with these needs and priorities, and the paucity of specific funds dedicated to tungiasis research, we have a developed and applied a rapid assessment method in Ceará State in Northeast Brazil. This method relies on the snowball system and is based on an online open questionnaire for health care professionals and other key stakeholders, to obtain basic data on tungiasis [

10]. Here we present an analysis of this state-wide assessment, serving as a basis for the planning of evidence-based control measures, and in-depth field studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Study Design

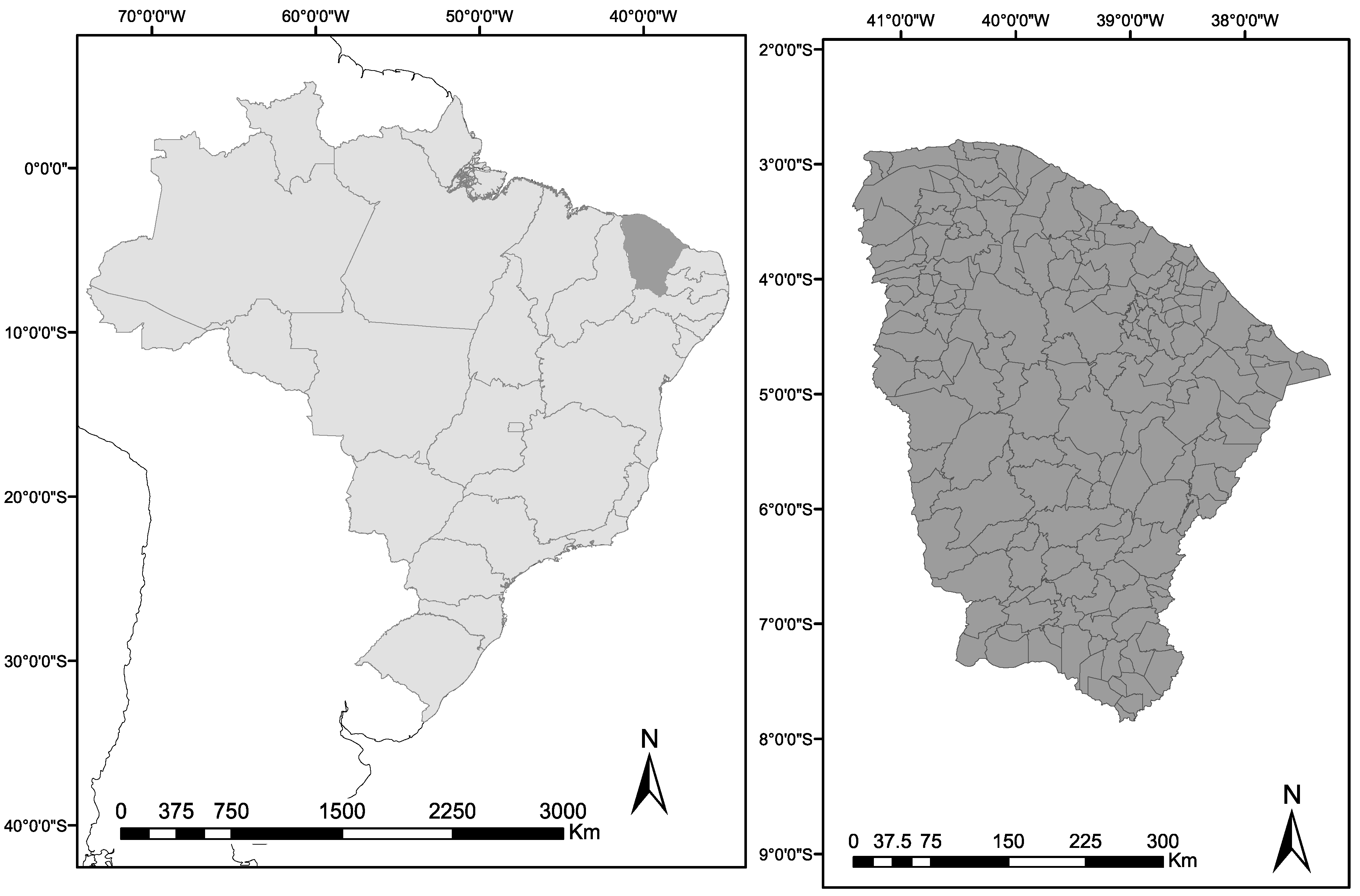

Within the broader context of assembling nationwide data on the occurrence of tungiasis in Brazil, we selected Ceará State in northeast Brazil for a case study (

Figure 1). Ceará State consists of 184 municipalities (population about 9.2 million). The climate is predominantly semiarid with irregular rainfalls, usually concentrated in three months (February to April) [

11,

12].

Previous population-based studies have shown that tungiasis occurs commonly in several municipalities of the state [

8,

13,

14,

15], but the distribution of the disease throughout the state is not known. Here we analyzed the respective data set regarding occurrence of tungiasis and severe disease in all municipalities of Ceará State. Data were collected from online survey tool from March to September 2021, as described in detail previously [

10].

2.2. Variables, data set and statistical analysis

In total, there were 1,265 individual data entries available. The number of entries for each of the 184 municipalities varied considerably, from 1 to 104. The present analysis used the municipalities as observation units. For this purpose, the individual entries were merged into one datum per municipality.

First, we performed a descriptive analysis of these 184 entries: occurrence of human and animal tungiasis and severe disease, stratified by periods (during this study – year 2021 or in the past - before the year 2021); seasonality of occurrence; existence of specific control programs. Secondly, descriptive spatial analysis was carried out using ArcGIS 9.2 for analysis and construction of thematic maps.

3. Results

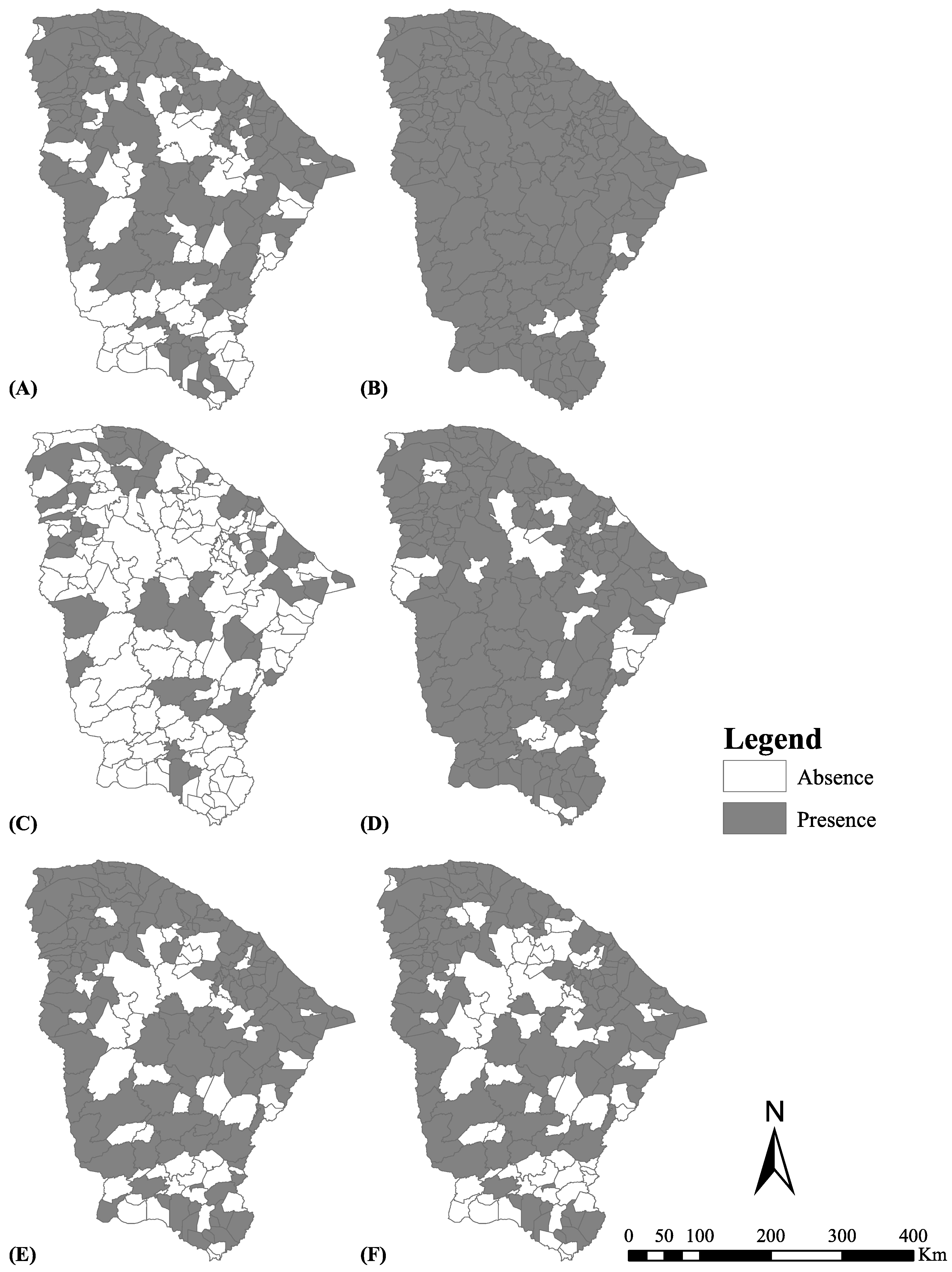

A total of 181 (98.3%) municipalities reported the occurrence of tungiasis in the past or currently, and 120 (65.2%) reported current occurrence (

Table 1). There were only three municipalities (namely Iracema, Larvras da Mangabeira and Várzea Alegre) that did not report tungiasis. However, only one to three responses (online data entries) were available for these municipalities. A total of 155 (84.2%) municipalities reported severe cases of tungiasis in the past or currently, and 47 (25.5%) severe current cases.

Respondents described severe cases observed in their communities as: “amputation of fingers and toes”; “simultaneous lesions in an entire family”; “multiple injuries at a child’s hands”; “secondary infection”; “person with walking difficulties”; “amputation of the toes of a diabetic lady”; “lesions on the buttocks”; “loss of nails”; “children needed hospital care to remove the fleas”; “death due to worsening”; “hospitalization”; “children from pig-raising families, who did not have adequate family support and who needed the guardianship council to refer the case to hospital care”.

About 72% of municipalities reported tungiasis in animals (

Table 1). Most mentioned dogs (n=97) and pigs (80) as affected animal species, followed by cats (50), horses (20), cattle (8) and goats (6). In animals, severe cases were described as: “tungiasis leading to death”; “swollen and bleeding paws”; “pigs with exaggerated lesions”; “occurrence of secondary infections”; “mutilation”; “loss of ability to walk”; “loss of nails”; “apathy”; “loss of weight and appetite”; “lesions on teats”; “loss of the hoof”; “loss of limbs”.

Most municipalities mentioned seasonality for tungiasis occurrence. There was no report of any specific tungiasis control program in Ceará state.

Figure 2 depicts the distribution of the municipalities regarding the current and past occurrence of tungiasis and severe tungiasis, and occurrence in animals.

4. Discussion

This is the first systematic study on tungiasis, covering a broad and complete geographic area. Our data based on a previously developed rapid assessment method show that tungiasis and severe tungiasis commonly occur in Ceará state and that this ectoparasitosis is a significant public health issue in the region. Tungiasis occurs in all regions of Ceará state, independent from the predominant ecosystem. Severe cases in humans and animals were also described.

Rapid assessment methods have been developed for a variety of Neglected Tropical Diseases, as they generate data for disease control measures quickly, easy and at low cost [

10]. Here we described tungiasis patterns in Ceará, based on primary data, also regarding severity, and temporal, zoonotic and seasonal aspects. Our study provided data on a vast geographic area, and the online questionnaire method can be easily adapted to other regions and infectious diseases. For example, this approach can be expanded to other Neglected Tropical Diseases, to elaborate joint control measures on the state, national and regional levels, especially in settings with well-established health systems.

Severe cases were reported from a high number of municipalities, evidencing an urgent need for the implementation of systematic control measures. In the case of massive infection, chronic inflammation, difficulty walking, deformation of digits, loss of toenails and superinfection with pathogenic bacteria are common [

4,

7]. During past decades – mostly because of increasing urbanization and better living conditions – the number of affected municipalities and of those reporting severe cases has been reduced. However, in our study, hospitalization and even deaths were still mentioned by key stakeholders.

Tungiasis is a zoonosis, and in fact, the majority of municipalities reported tungiasis also in animals. In our study dogs, pigs and cats were most commonly mentioned. These domestic animals have been considered the most important animal reservoirs [

1,

7,

14,

17]. However, farm animals are also affected, which may pose an economical threat to their owners. In fact, in our study, severe disease in animals leading to considerable economic loss were described, including infections leading to loss of limbs and death. In addition, rats and sylvatic animals serve as animal reservoirs. Eggs are expelled from penetrated female fleas, and this is how infected humans, domestic animals and sylvatic animals spread the ectoparasite in the communities. In the environment, under favorable temperature and humidity conditions, the eggs develop into larvae and pupae [

7].

Considering the complex life cycle and the abundance of reservoirs, a multisectoral One Health approach is needed for sustainable control of tungiasis in highly affected communities [

2]. In resource-poor communities, high attack rates are observed on the compounds and inside houses, as a consequence of precarious housing conditions, presence of animals, abundant waste scattered around, and low educational level. In addition to the focus on human and animal reservoirs, off-host stages need to be reduced, and high density breeding sites eliminated – in the communities, and inside houses. This will considerable increase the quality of life of the affected populations. A variety of disciplines should thus work hand in hand within the One Health approach [

18]. These would include not only human and veterinary medicine, but also biology, architecture, and social sciences, among others [

7].

Seasonality of the occurrence of tungiasis has been well reported [

4,

19,

20]. Usually, there are only a few cases during the rainy season and higher incidences and consequently prevalences during the dry season [

21]. Indeed, in our study, many respondents were aware of this phenomenon, and many municipalities reported an increase in the number of cases in the dry season. Control measures should be planned and timed in line with the seasonal variation, preventing severe cases during the high transmission season.

Our study is subject to limitations. There was a considerable variety of the number of respondents by municipality, and in addition the size of municipalities differed considerably. With a higher number of respondents, the probability of positive responses increased, and underreporting of tungiasis may have occurred especially in the case of few responses. Thus, it can be assumed than tungiasis may also occur (or occurred in the past) in the municipalities with few responses. It was also observed that a low number of responses was related to personal engagement of individuals in their respective municipalities, size of municipalities, and other factors.

During the data collection period, many community health agents were heavily involved with measures directed toward the covid-19 pandemic, which may have reduced participation in several municipalities [

22]. Some survey respondents were mourning relatives, or diseased with covid-19.

Similarly, it can also be assumed that severe tungiasis was considerably underreported in our study, as severe disease may go unnoticed by many health care providers: most heavily affected patients are often living in remote settings in the hinterland, hide themselves as a result of embarrassment and bullying, and do not have easy access to health care [

23]. Tungiasis is usually not perceived as an important condition, neither by the populations affected nor by decision makers or health personnel, as well are often no district or countrywide control programs [

16].

5. Conclusions

Our study identified the geographic distribution of both human and animal tungiasis and severe disease on the municipality level in Ceará State. The results serve as a first step to fill the gap of missing data on the geographic distribution of tungiasis in endemic regions. This is important to design focused and evidence-based control measures. There was not a single municipality with an established tungiasis disease control program, highlighting further the need for action. In-depth studies should be performed, focusing on the mostly affected areas within the municipalities, to define areas to be targeted for intervention measures. An integrated One Health approach is paramount.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Nathiel Silva, Claudia Calheiros and Jorg Heukelbach; Data curation, Nathiel Silva, Carlos Alencar and Jorg Heukelbach; Formal analysis, Nathiel Silva, Claudia Calheiros, Carlos Alencar and Jorg Heukelbach; Investigation, Nathiel Silva and Jorg Heukelbach; Methodology, Nathiel Silva and Jorg Heukelbach; Resources, Nathiel Silva and Jorg Heukelbach; Supervision, Carlos Alencar and Jorg Heukelbach; Validation, Claudia Calheiros, Carlos Alencar and Jorg Heukelbach; Writing – original draft, Nathiel Silva and Jorg Heukelbach; Writing – review & editing, Nathiel Silva, Claudia Calheiros, Carlos Alencar and Jorg Heukelbach.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study complied with the National Health Council Resolution number 466 of October 12, 2012 and was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Federal University of Ceará no. 4.919.773 of August 20, 2021.

Acknowledgments

We thank participants in the municipalities for providing information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harvey, T.; Linardi, P.M.; Carlos, R.S.A.; Heukelbach, J. Tungiasis in domestic, wild, and synanthropic animals in Brazil. Acta Tropica 2021, 222, 106068. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: a road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010352. (accessed on 10 Mar 2023).

- Deka, M.A.; Heukelbach, J. Distribution of Tungiasis in Latin America: Identification of Areas for Potential Disease Transmission Using an Ecological Niche Model. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022, 5, 100080. [CrossRef]

- Saboyá-Díaz, M.I.; Nicholls, R.S.; Castellanos, L.G.; Feldmeier, H. Current status of the knowledge on the epidemiology of tungiasis in the Americas. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2022, 46, e124. [CrossRef]

- Heukelbach, J.; Tungiasis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2005, 47(6), 307–13. [CrossRef]

- Ariza, L.; Seidenschwang, M.; Buckendahl, J.; Gomide, M.; Feldmeier, H.; Heukelbach, J. Tungíase: doença negligenciada causando patologia grave em uma favela de Fortaleza, Ceará. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2007, 40(1), 63-7. [CrossRef]

- Heukelbach, J.; Harvey, T.V.; Calheiros, C.M.L. Tunga Spp. and Tungiasis in Latin America. In: Mehlhorn, H.; Heukelbach, J. (eds) Infectious Tropical Diseases and One Health in Latin America. Parasitology Research Monographs 2022, Springer, Cham, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ariza, L.; Wilcke, T.; Jackson, A.; Gomide, M.; Ugbomoiko, U.S.; Feldmeier, H.; Heukelbach, J. A simple method for rapid community assessment of tungiasis. Trop Med Int Health 2010, 15(7),856-64. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Report of a WHO informal meeting on the development of a conceptual framework for tungiasis control: virtual meeting, 11-13, January 2021. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland 2022. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/363972.

- Heukelbach, J.; Silva, N.S. A rapid assessment method for the estimation of the occurrence of epidermal parasitic skin diseases in Brazil: tungiasis and scabies as case studies. One Health Implement Res 2023, 3, 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/ohir.2022.26.

- IPECE - Instituto de Pesquisa e Estratégia Econômica do Ceará. Sistema de Informações Geossocioeconômicas do Ceará 2022. Available from: http://ipecedata.ipece.ce.gov.br/ipece-data-web (accessed on 10 Mar 2023).

- Silva, N.S.; Alves, J.M.B.; Silva, E.M. Avaliação da relação entre a climatologia, as condições sanitárias (lixo) e a ocorrência de arboviroses (dengue e chikungunya) em Quixadá-CE no Período entre 2016 e 2019. Rev Bras Met 2020, 35(3), 485-92. [CrossRef]

- Pilger, D.; Schwalfenberg, S.; Heukelbach, J.; Witt, L.; Mencke, N.; Khakban, A.; Feldmeier, H. Controlling tungiasis in an impoverished community: An intervention stud. Plos Negl Trop Dis 2008, 2(10), e324. [CrossRef]

- Heukelbach, J.; Costa, A.M.; Wilcke, T.; Mencke, N.; Feldmeier, H. The animal reservoir of Tunga penetrans in severely affected communities of north-east Brazil. Med Vet Entomol 2004, 18(4),329-35. [CrossRef]

- Feldmeier, H.; Eisele, M.; Sabóia-Moura, R.C.; Heukelbach, J. Severe tungiasis in underprivileged communities: case series from Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2003, 9(8), 949-55. [CrossRef]

- Heukelbach, J.; Ariza, L.; Adegbola, R.Q.; Ugbomoiko, U.S. Sustainable control of tungiasis in rural Nigeria: a case for One Health. One Health Implement Res 2021, 1, 4–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/ohir.2021.01.

- Ugbomoiko, U.S.; Ariza, L.; Heukelbach, J. Pigs are the most important animal reservoir for Tunga penetrans (jigger flea) in rural Nigeria. Trop Doct 2008, 38(4),226-227. [CrossRef]

- Heukelbach, J. One health & implementation research: Improving health for all. One Health Implement Res 2020, 1, 1–3. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/ohir.2020.01.

- Heukelbach, J.; Wilcke, T.; Harms, S.G.; Feldmeier, H. Seasonal variation of tungiasis in an endemic community. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005, 72(2),145-49. [CrossRef]

- Heukelbach, J.; Jackson, A.; Ariza, L.; Calheiros, C.; Soares, V.; Feldmeier, H. Epidemiology and clinical aspects of tungiasis (sand flea infestation) in Alagoas State, Brazil. J Infect Dev Ctries 2007, 1, 202–9.

- Harvey, T.V.; Heukelbach, J.; Assunção, M.S.; Fernandes, T.M.; da Rocha, C.M.; Carlos, R.S. Canine tungiasis: High prevalence in a tourist region in Bahia state, Brazil. Prev Vet Med 2017, 139(part A), 76-81. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, L.R.F.S.; Kendall, C. The COVID-19 pandemic and the disaster of the response of a right-wing government in Brazil. One Health Implement Res. 2021, 1, 80-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/ohir.2021.11.

- Miller, H.; Ocampo, J.; Ayala, A.; Trujillo, J.; Feldmeier, H. Severe tungiasis in Amerindians in the Amazon lowland of Colombia: A case series. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13(2), e0007068. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).