1. Introduction

In previous epidemiological studies, we have shown that increased levels of Galectin-4 (Gal-4) are linked with prevalent and incident diabetes [

1], as well as increased risk of future myocardial infarction, heart failure, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality [

2].

Gal-4 is a gastrointestinal tract protein involved in apical trafficking of proteins, including dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), which accumulates intracellularly in Gal-4-depleted mice [

3]. Soluble and membrane-bound DPP-4 inactivate gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) that are largely responsible for the incretin effect [

4]. The latter is defective in individuals with diabetes [

5], leading to cardio-metabolically adverse effects [

6]. Recent evidence suggests that incretin-based antihyperglycemic agents, including DPP-4 and GLP-1 receptor agonists, exert beneficial effects in patients with diabetes who suffer ischemic stroke by reducing infarct size and promoting recovery [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Thus, we tested whether Gal-4 increases after stroke dependent on the metabolic syndrome in a mouse model of stroke. To clinically validate results obtained in this experimental model, we tested for Gal-4 association with prevalent stroke in a population-based cohort study.

2. Results

2.1. Gal-4 plasma levels increase after experimental ischemic stroke

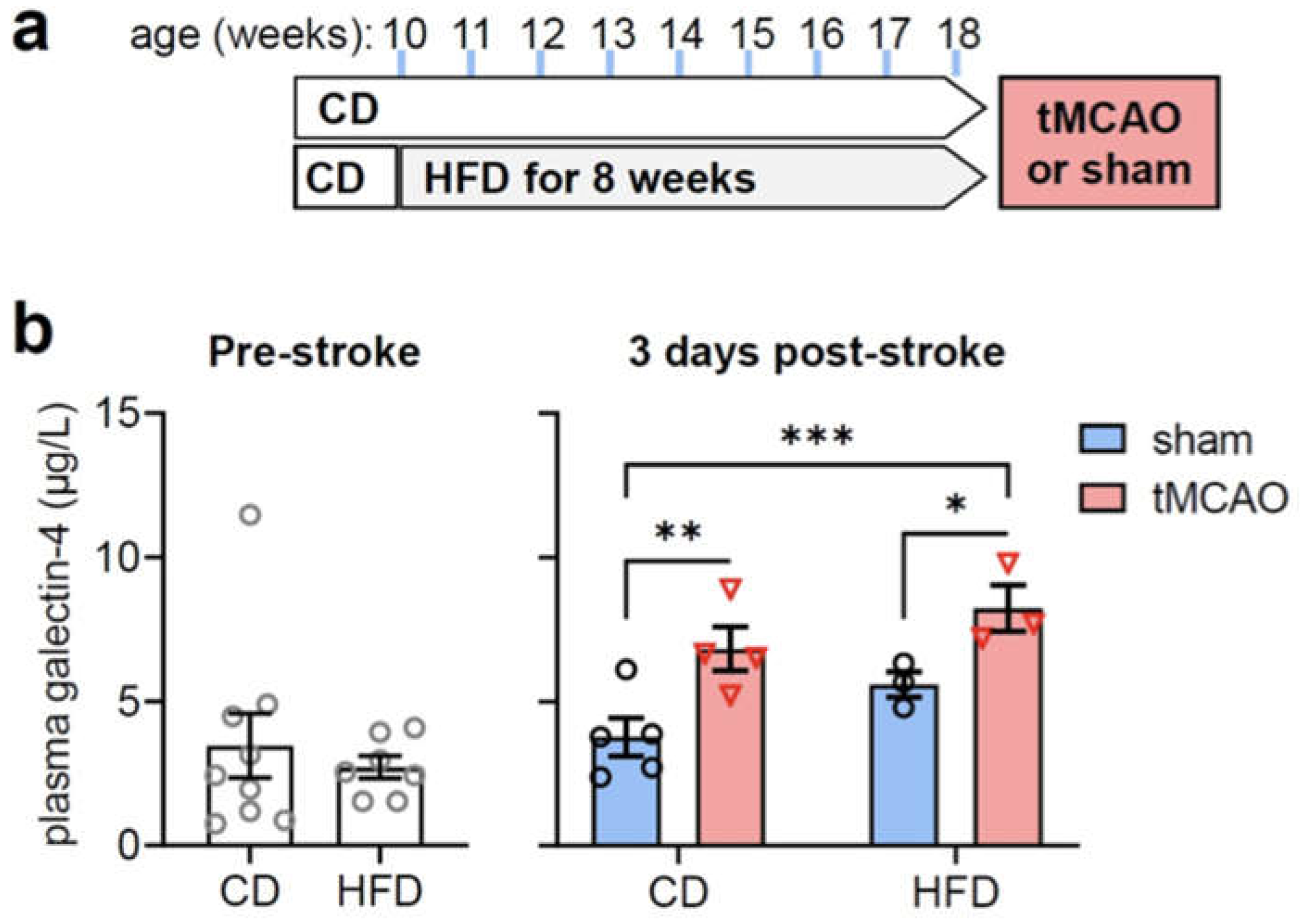

To induce metabolic syndrome, mice were fed a HFD for 8 weeks before stroke induction (

Figure 1a). HFD over 8 weeks led to increased body weight (in g: 29.8±0.9 in CD, 40.5±1.2 in HFD, P<0.001), plasma glucose (in mmol/L: 4.4±0.3 in CD, 6.2±0.5 in HFD, P=0.007) and plasma insulin (in µg/L: 3.2±1.8 in CD, 15.8±5.7 in HFD, P=0.035).

Stroke induced by tMCAO was confirmed by low neuro-score results (8.8±5.2 in CD, 6.7±3.2 in HFD) and apparent ischemic lesions (41±13% in CD, 37±15% in HFD).

While HFD had negligible impact on plasma Gal-4, tMCAO resulted in increased Gal-4 levels, as measured 3 days after stroke (

Figure 1b; ANOVA effects: diet F(1,11)=5.00, P=0.047, stroke F(1,11)=15.50, P=0.002, interaction F(1,11)=0.081, P=0.781).

2.2 Gal-4 Associates with prevalent stroke

Subjects with prevalent ischemic stroke (n=59) were older, more often men, had diabetes mellitus to higher extent and were more often treated for hypertension. Gal-4 was significantly higher in subjects with prevalent ischemic stroke then in subjects without (

Table 1).

In logistic regressions, Gal-4 was associated with prevalent ischemic stroke in an unadjusted model and also following adjustments for age and sex and well as main covariates related to weight, diabetes and cardiovascular health (

Table 2). In univariate regression analyses, each doubling in Gal-4 concentration was associated with higher BMI (β 0.87; P=8.3x10-8), and higher probability of antihypertensive treatment (OR 2.24 [1.90-2.63]; P=2.2x10-22). Gal-4 had no significant associations with systolic blood pressure (P=0.678).

3. Discussion

This is the first study to show higher plasma Gal-4 levels in patients with prevalent stroke. A verification in a murine model of experimental stroke supports an interaction between Gal-4 plasma levels and stroke. Although increases of Gal-4 associate with higher BMI in the tested human cohort, HFD feeding has negligible impact on plasma Gal-4 levels in mice. Herein presented results suggesting that impaired fasting glucose and diabetes status are not linked to alterations of Gal-4 levels in contrast to results from previous epidemiological studies that report associations between high Gal-4 levels and prevalent as well as incident diabetes [

1]. However, another study reports similar relationships between Gal-4 and incidence of myocardial infarction, heart failure as well as cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [

2], supporting the notion that changes in Gal-4 levels generally associate with occurrence of cardiovascular events, including stroke. In line with this, a recent study annotated Gal-4 with prognosis in heart failure patients [

16].

Gal-4 has been reported to involve in immunoregulatory functions through the activation and differentiation of monocytes [

17], which have been proposed as central players in the detrimental innate proinflammatory response post-stroke [

18]. Besides inflammation, the formation of new vessels through angiogenesis is thought to participate in functional stroke recovery [

19]. Gal-4 has been linked to augmented secretion of circulating cytokines responsible for endothelial activation related to angiogenesis and thus, cancer metastasis [

20]. Earlier studies supported its role in proliferation and migration of different cell types [

21], emphasizing a potential involvement in angiogenic processes that may also occur post-stroke. Similarly, arteriogenesis as a major process to improve collateral flow has been associated with Gal-4 [

22]. As patients with good collateral flow experience more favorable stroke outcomes and metabolic risk factors such as diabetes are associated with poor leptomeningeal collateral status [

23], investigating the role of Gal-4 in this respect may be promising.

Taken together, the relatively sparse knowledge base available on the role of Gal-4 in stroke pathology and related processes as well as its relationship to risk factors for stroke, such as metabolic syndrome and diabetes necessitates mechanistic and clinical studies to investigate the relative potential of Gal-4 as a prognostic marker for stroke outcome or even its potential as therapeutic target.

3.1. Study Limitations

The MMP-Res cohorts consist of mainly elderly, white European men. Thus, our findings might not be generalizable to all populations. As common to all observational studies, no conclusions about causality can be drawn.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mouse Study

Male C57BL/6J mice (8-weeks old; Taconic, Skensved, Denmark) were group-housed on a 12h light-dark cycle in enriched cages with access to food and water ad libitum and, after acclimatization, were fed high-fat (HFD, 60% fat kcal) or control diets (CD, 10% fat kcal) (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ-USA) as previously described [

11]. Experimenters were blinded to group allocation during sample processing and data analysis.

4.1.1. Mouse model of stroke

Transient middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion was performed as previously described 12. Briefly, the MCA was transiently occluded using a monofilament (9–10 mm coating length, 0.19±0.01 mm tip diameter; Doccol, Sharon, USA) in anesthetized mice (isoflurane in 70% N2O, 30% O2). Reperfusion was initiated after 60 minutes. Cerebral blood flow was monitored using Laser Doppler flowmetry (Moor Instruments, Axminster, UK). The same protocol without occlusion was used for sham surgery. Neurological function was evaluated using the sum of focal and general scores ranging between 0 (no deficits) and 56 (the poorest performance) [

12]. Coronal brains slices (1-mm thick) were stained with 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, #93140), and infarct area was determined and presented as percentage of contralateral hemisphere [

12].

4.1.2. Plasma analyses

Pre-surgery blood from the saphenous vein and post-stroke blood withdrawn from vena cava prior transcardial perfusion was collected into EDTA-coated tubes (Sarsedt, #41.1395.105), and separated by centrifugation at 1000×g for 10 minutes at room temperature. Plasma glucose was measured using the glucose oxidase method coupled to a peroxidase reaction oxidizing the AmplexRed reagent (#A12222, Invitrogen, ThermoFisher), as detailed before [

13]. Commercially available ELISA kits were used to determine plasma insulin (#10-1247-10, Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) and Gal-4 (#NBP2-76725, Novus Biologicals, Bio-Techne).

4.1.3. Statistics

Data was analyzed with Prism 9.3.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA-USA). After normality testing (Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests), data were analyzed by either Student t-tests (HFD effect pre-stroke) or 2-way ANOVAs with diet and stroke as factors. Significant diet, stroke or interaction effects were followed by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) tests for independent comparisons.

4.2. Human study

Within the Malmö Preventive Project [

14] Re-Examination cohort, a sub-sample of participants was randomly selected based on glucometabolic status [

15], i.e., 1/3 normoglycemic; 1/3 with impaired fasting glucose (IFG), and 1/3 with diabetes (n

total=1792). Blood samples provided by 1737 individuals were analyzed with proximity extension assay technology (Proseek Multiplex CVD III from Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden). The CVD III panel consists of 92 proteins, among them Galectin-4, with either established or proposed associations with CVD, inflammation, and metabolism. Complete data for all co-variates was available in 1688 subjects.

4.2.1. Examinations

Standardized methods were used to measure anthropometrics and blood pressure, as described elsewhere [

15]. Fasting plasma glucose and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were analyzed using Beckman Coulter LX20 (Beckman Coulter, Brea, USA) at Department of Chemistry, Skåne University Hospital, Malmö. Fasting blood samples for proteomic analyses were stored at -80°C until time of analysis.

4.2.2. Definitions

Data on prevalent ischemic stroke was collected through regional and national registers, defined as ICD9 code 433-434, or ICD10 codes I63.0-I63.9. IFG was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥5.6 mmol/L. Prevalent diabetes was defined as either previously known diabetes or new-onset diabetes (two separate measurements of fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L or one measurement ≥11.1 mmol/L) [

15]. Smoking was self-reported and defined as present smoking. Anti-hypertensive treatment was defined as use of any blood pressure lowering medicine and retrieved through The National Prescribed Drug Register (starting in 2005).

4.2.3. Statistics

Associations between Gal-4 and prevalent ischemic stroke were explored using logistic regression models in three steps: 1) unadjusted; 2) adjusted for age and sex (Model 1), and 3) adjusted for body mass index, systolic blood pressure, prevalent IFG/diabetes, HDL-cholesterol, antihypertensive treatment and smoking (Model 2). Groups were compared using students t-tests or χ²tests, where appropriate. Associations between Gal-4 and continuous variables were analyzed using univariate linear regressions, and associations between Gal-4 and binary variables using univariate logistic regressions.

Author Contributions

JPPV and HM performed mouse experiments and analyzed data. AM, JMND, AJ and MM designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The MPP was funded by the Heart and Lung Foundation of Sweden (2004045806), Region Skåne (PMN), Merck Sharp & Dohme, Hulda and E Conrad Mossfelts Foundation and Ernhold Lundströms Foundation. Further funding was provided from the Swedish Research council (2019-01130, JMND and 2022-00973, MM), Diabetesfonden (Dia2019-440, JMND), Direktör Albert Påhlssons Foundation (JMND, AM), Hjärnfonden (FO2021-0112, AM), Crafoord Foundation (20220654, AM, 20220566, MM) the Heart and Lung Foundation (20210354, MM), Stroke Riksförbundet (AM), German Academic Exchange Service (HM) and Sparbanken Stiftelse (V2021/1851, AM). The authors acknowledge generous financial support from The Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation, the Faculty of Medicine at Lund University and Region Skåne. JMND acknowledges support from the Lund University Diabetes Centre, which is funded by the Swedish Research Council (Strategic Research Area EXODIAB, grant 2009-1039) and the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (grant IRC15-0067).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Animal experiments were performed according to EU Directive 2010/63/EU and approved by the Malmö/Lund Committee for Animal Experiment Ethics (Dnr 5.8.18-08160/2021). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical review board of Lund University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from Steering Committee of the Malmö Preventive Project study by contacting data manager Anders Dahlin (anders.dahlin@med.lu.se), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available due to ethical and legal restrictions related to the Swedish Biobanks in Medical Care Act (2002:297) and the Personal Data Act (1998:204).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Molvin, J. et al. Using a Targeted Proteomics Chip to Explore Pathophysiological Pathways for Incident Diabetes– The Malmö Preventive Project. Scientific Reports 9, 272. (2019). [CrossRef]

- Molvin, J. et al. Proteomic exploration of common pathophysiological pathways in diabetes and cardiovascular disease. ESC Heart Failure 7, 4151-4158. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Delacour, D. et al. Galectin-4 and sulfatides in apical membrane trafficking in enterocyte-like cells. J Cell Biol 169, 491-501. (2005). [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D. J. & Nauck, M. A. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet 368, 1696-1705. (2006). [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M., Stöckmann, F., Ebert, R. & Creutzfeldt, W. Reduced incretin effect in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 29, 46-52. (1986). [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J., Maiseyeu, A., Davis, S. N. & Rajagopalan, S. DPP4 in cardiometabolic disease: recent insights from the laboratory and clinical trials of DPP4 inhibition. Circ Res 116, 1491-1504. (2015). [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. et al. Anti-inflammatory Effect of Glucagon Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist, Exendin-4, through Modulation of IB1/JIP1 Expression and JNK Signaling in Stroke. Exp Neurobiol 26, 227-239. (2017). [CrossRef]

- Filchenko, I., Simanenkova, A., Chefu, S., Kolpakova, M. & Vlasov, T. Neuroprotective effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist is independent of glycaemia normalization in type two diabetic rats. Diabetes and Vascular Disease Research 15, 567-570. (2018). [CrossRef]

- Holman, R. R. et al. Effects of Once-Weekly Exenatide on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 377, 1228-1239. (2017). [CrossRef]

- Marso, S. P. et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine 375, 311-322. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Serrano, A. M., Vieira, J. P. P., Fleischhart, V. & Duarte, J. M. N. Taurine and N-acetylcysteine treatments prevent memory impairment and metabolite profile alterations in the hippocampus of high-fat diet-fed female mice. Nutr Neurosci, 1-13. (2022). [CrossRef]

- Battistella, R. et al. Not All Lectins Are Equally Suitable for Labeling Rodent Vasculature. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, 11554 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J. M. N., Morgenthaler, F. D. & Gruetter, R. Glycogen Supercompensation in the Rat Brain After Acute Hypoglycemia is Independent of Glucose Levels During Recovery. Neurochem Res 42, 1629-1635. (2017). [CrossRef]

- Berglund, G. et al. Long-term outcome of the Malmo preventive project: mortality and cardiovascular morbidity. J Intern Med 247, 19-29. (2000). [CrossRef]

- Leosdottir, M. et al. Myocardial structure and function by echocardiography in relation to glucometabolic status in elderly subjects from 2 population-based cohorts: a cross-sectional study. American heart journal 159, 414-420.e414. (2010). [CrossRef]

- Rullman, E. et al. Circulatory factors associated with function and prognosis in patients with severe heart failure. Clinical Research in Cardiology 109, 655-672. (2020). [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-H., Shin, J.-S., Chung, H. & Park, C.-G. Galectin-4 Interaction with CD14 Triggers the Differentiation of Monocytes into Macrophage-like Cells via the MAPK Signaling Pathway. Immune Netw 19 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Urra, X. et al. Monocytes are major players in the prognosis and risk of infection after acute stroke. Stroke 40, 1262-1268. (2009). [CrossRef]

- Arai, K., Jin, G., Navaratna, D. & Lo, E. H. Brain angiogenesis in developmental and pathological processes: neurovascular injury and angiogenic recovery after stroke. Febs j 276, 4644-4652. (2009). [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. et al. Circulating galectins -2, -4 and -8 in cancer patients make important contributions to the increased circulation of several cytokines and chemokines that promote angiogenesis and metastasis. British Journal of Cancer 110, 741-752. (2014). [CrossRef]

- Etulain, J. et al. Control of Angiogenesis by Galectins Involves the Release of Platelet-Derived Proangiogenic Factors. PLOS ONE 9, e96402. (2014). [CrossRef]

- van der Hoeven, N. W. et al. The emerging role of galectins in cardiovascular disease. Vascular Pharmacology 81, 31-41. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Menon, B. K. et al. Leptomeningeal collaterals are associated with modifiable metabolic risk factors. Ann Neurol 74, 241-248. (2013). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).