1. Introduction

Polyphosphate (polyP) is a highly anionic inorganic polymer composed of phosphate monomers, and the length and cell-associated content of biological polyP are dependent on the type of organism, for example, bacteria and mammalian cells [

1]. Due to these differences and probably the simplicity of organisms compared to bacteria, the functions of polyP in mammalian cells are still poorly understood. From a practical point of view, it could also be said that delayed development and standardization of polyP quantification and preservation of biological samples have interfered with advances in the elucidation of polyP functions in mammalian cells.

However, recent challenges have enabled the convenient quantification of biological polyP levels using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) [

2,

3]. Although DAPI does not specifically bind to polyP [

4,

5,

6], the right shift of the wavelength selected for fluorometric analysis increases the specificity of polyP-dependent signals in the presence of cellular compounds that bind to DAPI [

2,

7]. The conventional quantification method that requires complete degradation of the monomer and purification is time-consuming and not suitable for comparison between medium and large sample sizes. However, the development of such fluorescent quantification techniques enables the handling of many samples. The remaining practical issue is the preservation of biological samples.

To overcome this issue, we optimized the preservation conditions for human platelets based on previously reported quantification methods [

7,

8,

9]. Among several possible protocols, fixation, removal of fixative, replacement with pure water, and preservation at −80 °C appear to be essential elements for successful preservation.

2. Experimental Design

Pure-platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) was prepared from the blood obtained from five non-smoking healthy male donors (age:24−62 years) using the double-spin method [

9,

10]. Platelet suspensions were prepared by centrifugation and resuspension in PBS. The basic scheme consisted of fixation (or not), replacement of solution (or not), preservation (4 or −80 °C), and quantification. The possible combinations of individual steps are listed in

Table 1.

In a preliminary study, because of practical difficulties, several protocols were excluded, and because of theoretical incompatibility, several protocols were not tested. Three possible protocols (expressed in bold letters) were tested as promising candidates in this study.

3. Procedure

3.1. Preparation of Pure Platelet-Rich Plasma and Platelet Suspension in PBS

The study design and consent forms for all procedures (project identification code: 2021-0126) were approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Participants at Niigata University (Niigata, Japan) and complied with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013.

Blood samples were collected from five non-smoking, healthy male donors (n = 6 or 7; ages 24–62 years). Despite having lifestyle-related diseases and taking medications, these donors (i.e., our team members and relatives) had no limitations in their daily activities. These donors were also negative for HIV, HBV, HCV, or syphilis infections. A prothrombin test was performed on all blood samples using a CoaguChek® XS (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and all results were normal. Platelet and other blood cell counts were measured using a pocH 100iV automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). Platelet distribution width (PDW), a conventional index for the variation in platelet volume, and mean platelet volume (MPV), a conventional index for the average size (volume) of platelets, were also determined.

Approximately 9 mL of peripheral blood was collected in plain glass vacuum blood collection tubes (Vacutainer®; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) containing 1.5 mL of an acid-citrate-dextrose solution. Whole blood samples were stored in a rotating agitator at an ambient temperature (18–22 °C) until use (<20 h). The samples were centrifuged horizontally at 415×g for 10 min (soft spin) (Kubota, Tokyo, Japan). The upper plasma fraction, which was ~1 mm above the interface of the plasma and red blood cell fractions, was collected and further centrifuged at 664×g for 3 min (hard spin) using an angle-type centrifuge (Sigma Laborzentrifugen, Osterode am Harz, Germany) to prepare P-PRP or to collect the resting platelet pellets for the preparation of platelet suspension in PBS. Platelet counts were adjusted to 2–3.0 × 105/µL.

3.2. Fixation and Preservation conditions

Platelets in the forms of P-PRP and PBS suspensions were fixed with ThromboFix (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA) for 20–24 h [

7]. For preservation at 4 °C, platelets were incubated without the removal of the fixative. For preservation at −80 °C, platelets were resuspended in pure water and immediately frozen at −80 °C. In both cases, it should be noted that the pipetting of the platelet suspension should be minimized. We have often observed that excessive or rough pipetting or vortexing significantly decreased platelet polyP levels.

3.3. Quantification of Platelet polyP Levels

PolyP quantification was performed as described previously [watanabe, Ushiki]. In brief, fixed platelets were centrifuged at 664×

g for 3 min, gently suspended in pure water, and incubated with DAPI (4 μg/mL) for 15 min at room temperature (18–22 °C). This mixture was directly subjected to fluorescence measurements using a fluorometer (FC-1; Tokai Optical Co., Ltd., Okazaki, Japan) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 425 and 525 nm, respectively, based on the red-shift fluorescence of DAPI bound to polyP [

2].

3.4. Preservation at 4°C

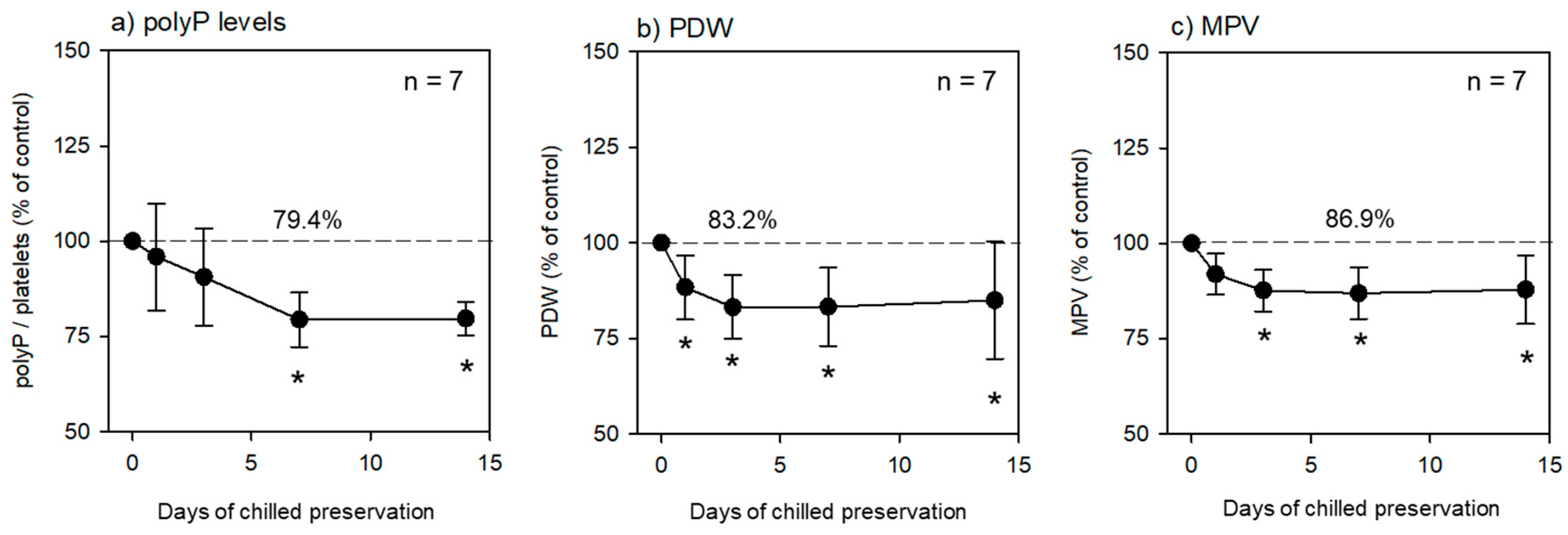

As shown in

Table 1 platelets in the fixative-containing PBS were preserved at 4 °C for the initial 24 h and further preserved without replacement of solution for up to 2 weeks. The time-course changes in polyP, PDW, and MPV levels are shown in

Figure 1. PolyP levels gradually decreased in a time-dependent manner after chilled preservation. PolyP levels at 1 week and later were significantly lower than those in the control at 0 h (

Figure 1a). Similarly, but more drastically, the PDW and MPV levels started to decrease immediately after chilled preservation (

Figure 1b,c).

3.5. Preservation at −80 °C

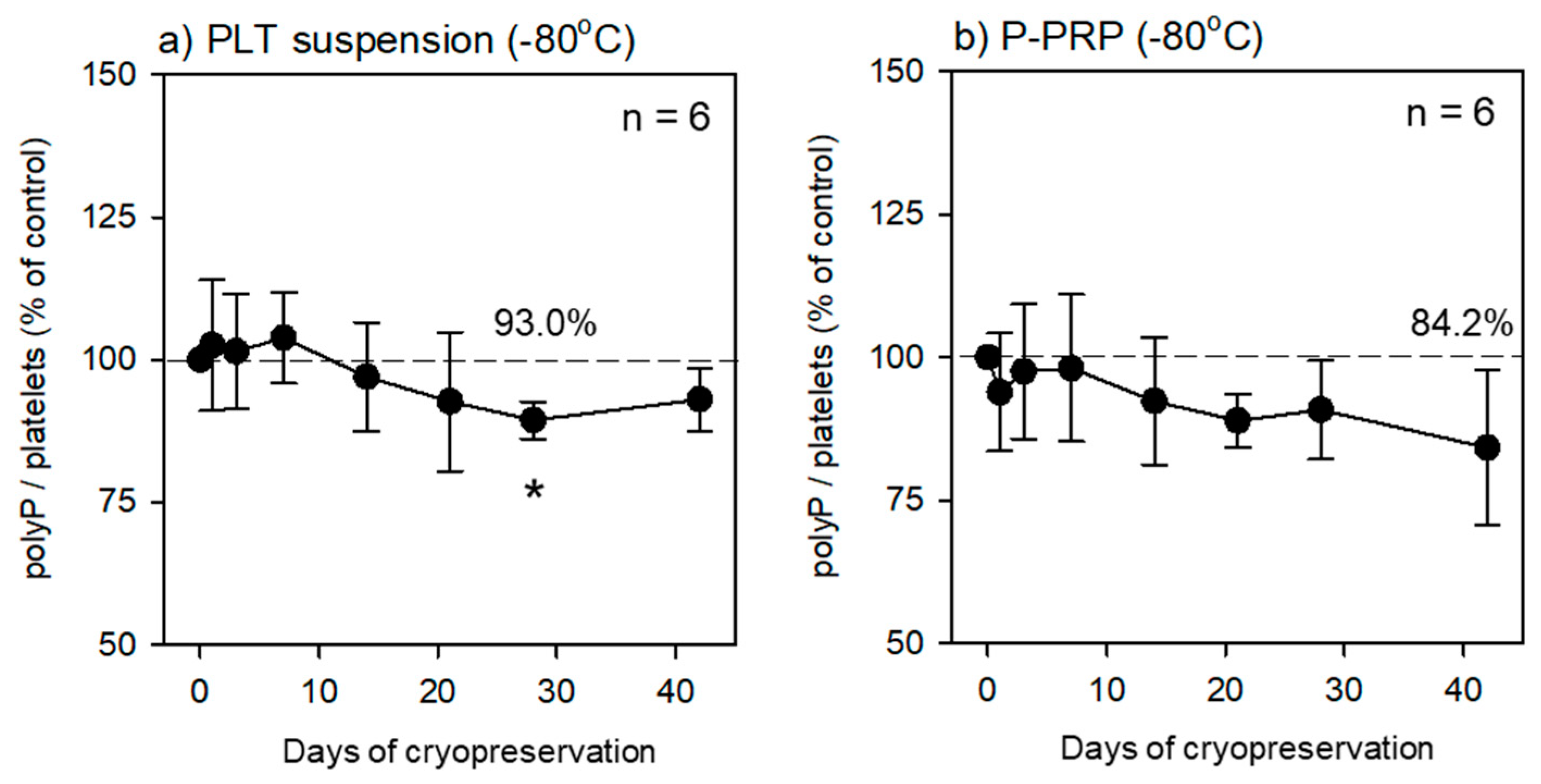

As shown in Table 2, platelets in the fixative-containing PBS were preserved at 4 °C for the initial 24 h. At the end of the initial preservation, the fixative-containing solution was replaced with pure water, and platelets were counted prior to cryopreservation at −80 °C. At each time point, the frozen platelets were thawed at room temperature and directly subjected to fluorescence quantification. The time-course changes in polyP levels are shown in

Figure 2. PolyP levels did not decrease significantly throughout the preservation period (~6 weeks). In addition, no significant reduction was observed, regardless of the initial solution type (i.e., PBS suspension or plasma suspension) used for fixation.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

To compare the mean values, a non-parametric analysis was performed using the Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison method. Differences (vs. controls) were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

4. Expected Results and Discussion

In previous studies [

7,

8,

9], pure water was found to be the most suitable solution for platelet suspensions for fluorometric polyP quantification. Furthermore, in a preliminary study, we found that platelet suspensions, including the fixative, produced insoluble compounds after thawing and interfered with polyP quantification. Thus, in this study, we postulated that the fixative solution should be replaced with pure water prior to freezing. For biological samples, pH-controlled buffer solutions are generally accepted to be suitable for preservation. However, because we experienced that some additives for buffering action increased the fluorescent signals, we again chose pure water for preservation.

Even at −80 °C, phosphatases contained in the frozen biological samples may release inorganic phosphate from polyP, thus reducing the fluorescent signal. In this study, no significant decrease in polyP levels was observed for up to 6 weeks in frozen samples. However, a tendency toward decrease was observed. This was probably caused by spontaneous hydrolysis and dephosphorylation by platelet-associated phosphatases. The former possibility may be prevented by lowering the preservation temperature below −80 °C. The latter can be preserved by adding appropriate phosphatase inhibitors, if any, for further prolongation of stable preservation.

To discuss the necessity of fixation, we have only limited data. Without fixation, an appropriate range in the linearity of the calibration curve was not obtained for the frozen and thawed samples. The thawed solution became clouded by cell nano-debris and the linear range was always narrow. Unlike formalin, fixation with ThromboFix does not cause autofluorescence and, to some extent, reduces cloudiness. In addition, fixation may be beneficial for the stabilization of polyP on the plasma membrane and in cellular organelles such as dense granules. Further studies are required to clarify this possibility.

In conclusion, regardless of the initial forms of platelet suspension, the protocol in which the main elements are the replacement with pure water and freezing at −80 °C, was validated as optimized long-term preservation of platelet samples for fluorometric polyP quantification. This protocol enables us to save time, cost, and labor by allowing simultaneous polyP quantification of accumulated samples. Thus, this protocol can be utilized in medium- or large-cohort studies for polyP and to further clarify the functions of platelet polyP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.; methodology, T.K.; validation, T.U.; investigation, T.K., K.S., M.K., T.M., and T.U.; data curation, T.K. and T.U.; writing—original draft preparation, T.K., T.M., and T.U.; writing—review and editing, T.K. and T.U.; supervision, T.U.; project administration, T.U.; funding acquisition, T.U. and T.K. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI (#21K09932, #22K11496) and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (#21bk0104129h0001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study design and consent forms for all procedures (project identification code: 2021-0126) were approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Participants at Niigata University (Niigata, Japan) and complied with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects for publication of this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kus, F.; Smolenski, R.T.; Tomczyk, M. Inorganic Polyphosphate-Regulator of Cellular Metabolism in Homeostasis and Disease. Biomedicines. 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Omelon, S.; Georgiou, J.; Habraken, W. A cautionary (spectral) tail: red-shifted fluorescence by DAPI-DAPI interactions. Biochem Soc Trans. 2016, 44, 46-49. [CrossRef]

- Aschar-Sobbi, R.; Abramov, A.Y.; Diao, C.; Kargacin, M.E.; Kargacin, G.J.; French, R.J.; Pavlov, E. High sensitivity, quantitative measurements of polyphosphate using a new DAPI-based approach. J Fluoresc. 2008, 18, 859-866. [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.M.; Leonhardt, H.; Cardoso, M.C. DNA labeling in living cells. Cytometry A. 2005, 67, 45-52. [CrossRef]

- Tanious, F.A.; Veal, J.M.; Buczak, H.; Ratmeyer, L.S.; Wilson, W.D. DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) binds differently to DNA and RNA: minor-groove binding at AT sites and intercalation at AU sites. Biochemistry. 1992, 31, 3103-3112. [CrossRef]

- Grossgebauer, K.; Küpper, D. Interactions between DNA-binding fluorochromes and mucopolysaccharides in agarose-diffusion test. Klin Wochenschr. 1981, 59, 1065-1066. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Aizawa, H.; Masuki, H.; Tsujino, T.; Sato, A.; Kawabata, H.; Isobe, K.; Nakata, K.; Kawase, T. Fluorometric Quantification of Human Platelet Polyphosphate Using 4’,6-Diamidine-2-phenylindole Dihydrochloride: Applications in the Japanese Population. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 7257. [CrossRef]

- Ushiki, T.; Mochizuki, T.; Suzuki, K.; Kamimura, M.; Ishiguro, H.; Suwabe, T.; Kawase, T. Modulation of ATP Production Influences Inorganic Polyphosphate Levels in Non-Athletes’ Platelets at the Resting State. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022, 23, 11293. [CrossRef]

- Ushiki, T.; Mochizuki, T.; Suzuki, K.; Kamimura, M.; Ishiguro, H.; Watanabe, S.; Omori, G.; Yamamoto, N.; Kawase, T. Platelet polyphosphate and energy metabolism in professional male athletes (soccer players): A cross-sectional pilot study. Physiol Rep. 2022, 10, e15409. [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Aizawa, H.; Tsujino, T.; Isobe, K.; Watanabe, T.; Kitamura, Y.; Kawase, T. Fluorescent Cytochemical Detection of Polyphosphates Associated with Human Platelets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021, 22, 1040. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).