Submitted:

20 February 2023

Posted:

27 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Authors | Year | Animal model | ECLS support mode | Oxygenator design and membrane type | Priming volume | Effective membrane surface area | Flow during experiment | Duration of experiment | Tested DIN EN ISO 7199 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali et al. | 2014 | Sprague-Dawley rat | ECPR | Undisclosed design/vendor. Images show axial intraluminar flow oxygenator. Silicone membrane. | 8ml | Undisclosed | 5-6ml/min. Note: Flow was recorded at targeted ECPR-induced arterial pressure of 25-30mmHg. | 7.3±2.8min ECPR + 30 min weaning | Undisclosed | [21] |

| Fichter et al. | 2016 | Fischer-344-rat | Extracorporeal organ perfusion | Oxygenator named "Small Animal Micro Oxygenator” (SAMO). 3-layer of stacked membrane mats of undisclosed size (5-10cm edge length, approximated from published image). Polypropylene membranes. | 10ml for the entire ECC | Undisclosed | 2ml/min to perfuse isolated free flap | 8h | Undisclosed | [22] |

|

Warenits et al. |

2016 | Sprague–Dawley rat | ECPR | "SAMO"-oxygenator, please refer to Fichter et al. in this table. Membrane type undisclosed in this publication; group has worked with the same device with polypropylene fibers (see Magnet et al. and Fichter et al. in this table). | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | 100ml/kg/min | 10min + 43- 83 min weaning |

Undisclosed | [23] |

|

Wiegmann et al. |

2016 | In vitro | N/A | In-house design. Single-fiber-mat design. Not for actual ECLS therapy, but for experimental endothelialization of hollow fiber surfaces (oxygenator-like flow chamber). Membranes heparin/albumin-coated polymethylpentene fibers with experimental endothelialization. | 4.275ml | 18.75cm² fiber mat area which translates to 40cm² effective membrane surface area | 15, 30, 60, 90ml/min | 96h | Undisclosed | [24] |

| Magnet et al. | 2017 | Sprague–Dawley rat | ECPR, typical CBP features | "SAMO"-oxygenator, please refer to Fichter et al. in this table. Polypropylene membrane. | Undisclosed, 15ml for the entire ECC | Undisclosed | 100ml/kg/min with rats between 460 and 510g. | Max. 10 min + 30min weaning | Undisclosed | [25] |

| Chang et al. | 2017 | Wistar–Kyoto rat | ECPR | "Micro-1"-Rat oxygenator (Dongguan Kewei Medical Instrument Co., Ltd., Guangdong, China). Current commercial availability unclear. Axial flow oxygenator, with unknown intra- and extraluminar phases. Membrane type undisclosed in this publication; a different group also listed in this table has worked presumably with the same device by the same vendor with polypropylene fibers (Cho2021). | Undisclosed, 19-20 ml for the entire ECC | Undisclosed in this publication; Cho et al., also listed in this table, have worked likely with the same device by the same vendor with 500cm². | Undisclosed | 30min | Undisclosed | [26] |

| Madrahimov et al. | 2018 | C57BL/6 mouse | VV-ECMO | CPB-oxygenator, in-house design, axial intraluminar flow. Polypropylene membrane. Further information in other publications of Madrahimov et al. [27,28] | Undisclosed, <0.3ml in referenced [27] |

Undisclosed, 50 fibers of 80 mm each of undisclosed outer diameter | 1.5-5ml/min | 2h ECC + 5min weaning | Undisclosed | [29] |

|

Natanov et al. |

2019 | C57BL/6 mouse | VV-ECMO | CPB-oxygenator, in-house design, axial intraluminar flow. Polypropylene membrane. Please refer to Madrahimov et al. in this table for further information. | Undisclosed, 500µl for the entire ECC | Undisclosed, 50 fibers of 80 mm each of undisclosed outer diameter | Undisclosed, 3-5ml/min in [29] | 4h | Undisclosed | [30] |

| Vu et al. | 2019 | Sprague–Dawley rat | ECCO2R/ Dialysis | “M10” miniaturized dialyzer (Gambro, Lakewood, USA). Only previously described by the group in May et al. [31] and by Goldstein et al. [32]. Axial intraluminar flow oxygenator for neonates. Membrane so-called "AN69" hydrophilic hollow fiber made of s a copolymer of acrylonitrile and sodium methallyl sulfonate. See Thomas et al. [33] for details. | Undisclosed, but the device was designed for infants of 2-15kg. | 420cm² | 1ml/min | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | [34] |

|

Wollborn et al. |

2019 | Sprague–Dawley rat | VA-ECMO vs. ECPR | “OX” miniature gas exchange oxygenator, Living Systems Instrumentation, St. Albans City, Vermont, USA. Not further described in the study. Product description by the vendor shows an axial extraluminar flow oxygenator and a polypropylene membrane [20]. | Undisclosed, 6ml for entire ECC. Product sheet by the vendor: 1.6ml |

Undisclosed. Supplier: 115cm² [20] |

10-18ml/min, to reach target mean arterial pressure of 65 mmHg | 2.5h + undisclosed weaning | Undisclosed | [35] |

| Fujii et al. | 2020 | Sprague–Dawley rat | VA-ECMO | “Micro-1” (Senko Medical Instrument Mfg. Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Image shows an axial flow oxygenator, apparently with intraluminar flow. The oxygenator seems shorter but larger in diameter than other axial flow oxygenators in this table. The oxygenator could not be identified on the vendor’s product lists. Membrane type undisclosed. | Undisclosed, 8ml for entire ECC | Undisclosed | 70ml/kg/min | 2h | Undisclosed | [36] |

|

Edinger et al. |

2020 | Lewis rat | VA-ECMO | The “Micro-1” (please refer to Chang et al. in this table) was tested against the “SAMO” (please refer to Fichter et al. in this table) without further device specifications. Both membrane types undisclosed, both polypropylene in other publications with the same devices (Magnet et al and Cho et al. in this table) | SAMO: 7ml Micro-1: 3.5ml |

SAMO: 500cm² Micro-1: Published with 50cm² in potentially erroneous contrast to Cho et al. who published 500cm². |

90ml/kg/min | 2h | Undisclosed, gas transfer evaluated in CPB-study [37]. | [38] |

|

Wilbs et al. |

2020 | New Zealand white rabbit | VV-ECMO | In-house design with 40 stacked fiber mat layers. Despite incorporating genuine hollow fibers, the oxygenator was built non-functional regarding gas-transfer. It can be considered a simplified mock-oxygenator for hemocompatibility testing.. Polymethylpentene membrane. This fiber arrangement and fiber bundle design is similar to the RatOx-oxygenator. The stacked fiber mat layers have a cross-sectional flow area that is half of the RatOx. In consequence, the oxygenator requires twice as many fiber mat layers for the same effective surface area with potentially higher pressure drop. | Undisclosed | 263cm2. | 45ml/min | 4h | Undisclosed | [39] |

| Li et al. | 2021 | Sprague-Dawley rat | VV-ECMO | CPB-oxygenator, axial extraluminar flow. Produced by Xi'an Xijing Medical Appliance Co. Limited, Xi'An, China. The membrane type is undisclosed in the publication but following an inquiry at the supplier, polypropylene fibers are used. | 3ml | 200cm² | 80–90ml/kg/min | 3.5h | Undisclosed. | [40] |

| Cho et al. | 2021 | Sprague-Dawley rat | VA-ECMO vs. VV-ECMO | "Micro-1"-oxygenator; please refer to Chang et al. in this table. Polypropylene membrane. | 3.5ml | 500cm² | 50ml/min | 2h | Undisclosed | [41] |

| Fujii et al. | 2021 | Sprague-Dawley rat | VV-ECMO | Axial, extraluminar flow oxygenator. Note that in this publication, the figure suggests an intraluminal flow, while the original publication by Yamada et al. clearly states an extraluminar flow. This original publication covers two further slightly larger oxygenator variants. They also state that polypropylene fibers are used. [17] | Undisclosed, 8ml for entire ECC. Yamada et al. state a priming volume of 3ml [17]. | Undisclosed. Yamada et al.: 236cm² [17] |

50-60ml/kg/min | 2h | Yes, in Yamada et al. [17] | [16] |

| Umei et al. | 2021 | Sprague-Dawley rat | Mock-ECLS, pump-supported AV-cannulation | 3D-printed flow cell designed to simulate the local geometry, blood flow patterns and surface area to blood volume ratio of a commercially available oxygenator hollow fiber bundle. Unable to transfer gas. The membrane type is non-functional, clear acrylate resin (PR-48, Colorado Polymer Solutions, Boulder, CO). | 0.3ml for the oxygenator, 2.5ml for the entire ECC | 15cm² | 1.9ml/min | 8 h | Undisclosed | [13] |

|

Edinger et al. |

2021 | Lewis rat | VA-ECMO | "SAMO"-oxygenator; please refer to Chang et al 2017 in this table. Polypropylene membrane. | Undisclosed, 11ml for the entire ECC |

Undisclosed, 500cm² in publication of Edinger et al. (2020) in this table | 90ml/min | 2h | Undisclosed | [42] |

|

Govender et al. |

2022 | Syrian golden hamster | VA-ECMO | ECC-setup without oxygenator. | Not applicable | Not applicable | 15% of CO | 1.5h ECC | Not applicable | [43] |

| Greite et al. | 2022 | C57BL/6 mouse | VV-ECMO | Redesigned from [28]; CPB-oxygenator, in-house-design, axial intraluminar flow. Polypropylene membrane. | 200µl | Undisclosed, 50 fibers of 80mm each of undisclosed outer diameter | Undisclosed, 2.34-6.5ml/min in [28] | 2h ECC + 2h weaning | Undisclosed | [44] |

| Huang et al. | 2022 | Sprague-Dawley rat | VV-ECMO | See details from Li et al. in this table. | See details from Li et al. in this table. | See details from Li et al. in this table. | See details from Li et al. in this table. | 3h | Undisclosed | [45] |

| Zhang et al. | 2022 | Sprague-Dawley rat | VV-ECMO | See details from Li et al. in this table. | See details from Li et al. in this table | See details from Li et al. in this table | 80–90ml/kg/min | 2h | Undisclosed | [46] |

|

Edinger et al. |

2022 | Lewis rat | VA-ECMO | "Micro-1 "-oxygenator; please refer to Chang et al. 2017 in this table. Polypropylene membrane | 9ml | Undisclosed, 500cm² in publication by Cho et al. in this table | 90ml/min | 2h | Undisclosed | [47] |

|

Kharnaf et al. |

2022 | C57BL/6 mouse | VA-ECMO | “OX” miniature gas exchange oxygenator; please refer to Wollborn et al. in this table. | 1.6ml oxygenator priming (NaCl, Hetastarch,), 2 ml in remaining ECC (blood from two donor mice) | 115cm² (supplementary Materials) | 3–5ml/min | 1h | Undisclosed | [48] |

|

Alabdullh et al. |

2022 | In vitro | N/A | In-house design. Single-fiber-mat design. Not for actual ECLS therapy, but for experimental endothelialization of hollow fiber surfaces (oxygenator-like flow chamber). The oxygenator design is an advancement of the previously published device by Wiegmann et al. in this table. Heparin/albumin-coated polymethylpentene fibers with endothelialization. | 4ml | 19cm² | Static | 6h and 24h | Undisclosed | [49] |

Materials and Methods

Oxygenator design:

In-vitro proof-of-concept:

3. Results

Oxygenator design:

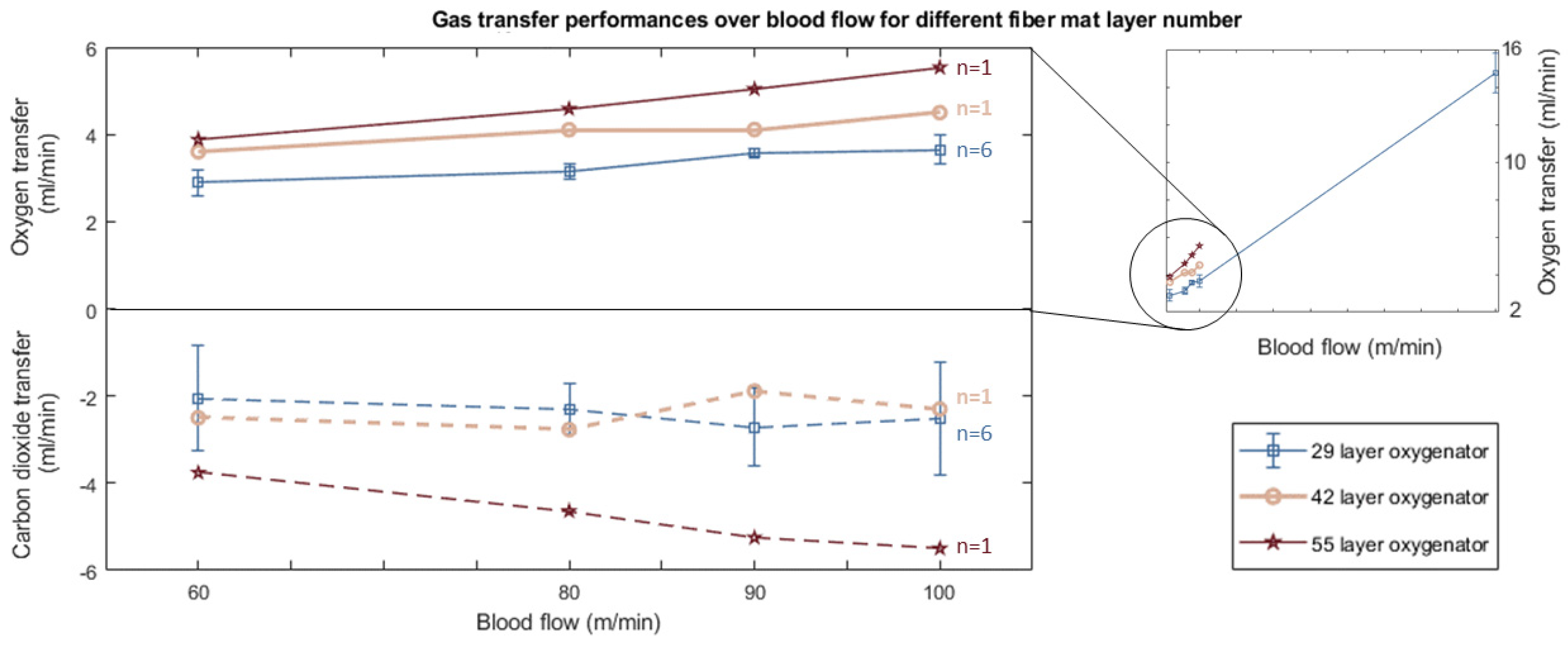

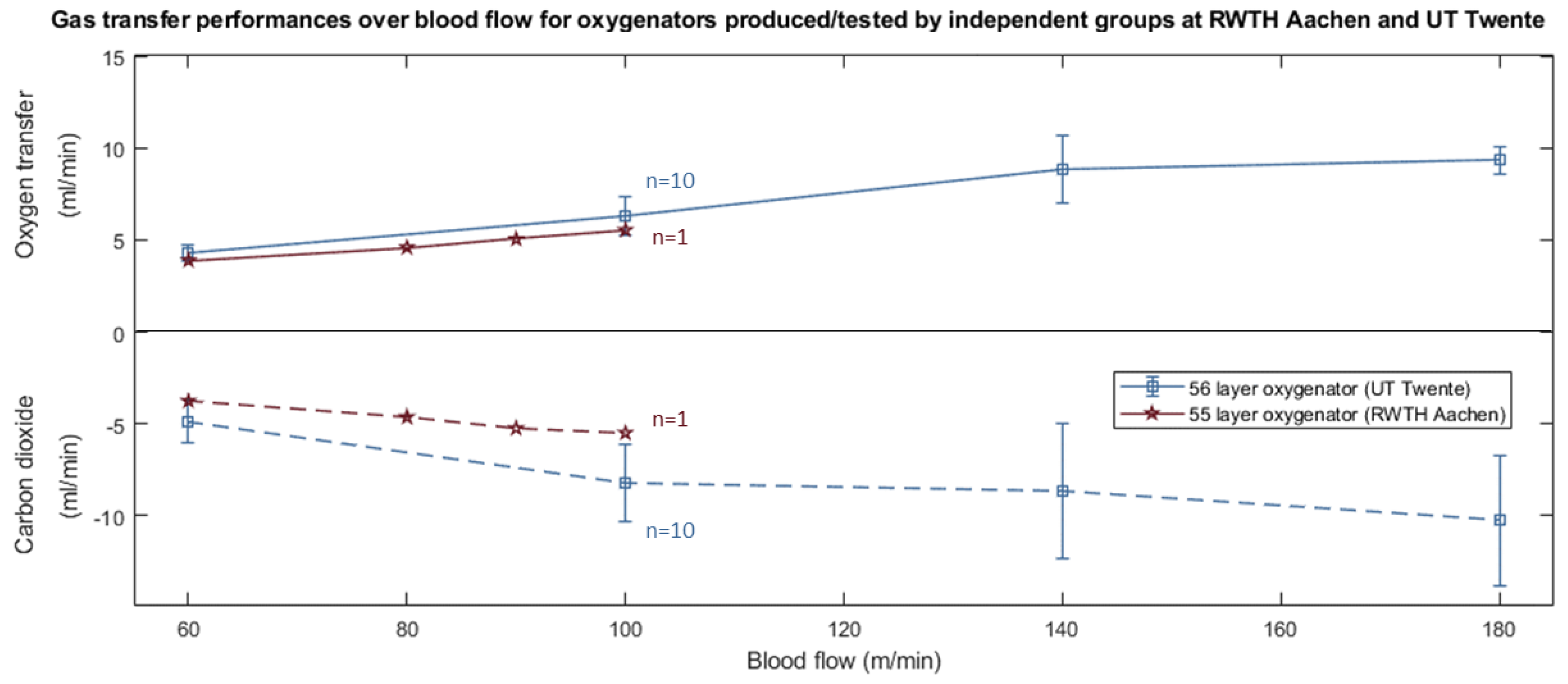

In-vitro proof-of-concept:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and outlook

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tramm, R.; Ilic, D.; Davies, A.R.; Pellegrino, V.A.; Romero, L.; Hodgson, C. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD010381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannon, W.D.; Trindade, A.J.; Stokes, J.W.; Casey, J.D.; Benson, C.; Patel, Y.J.; Pugh, M.E.; Semler, M.W.; Bacchetta, M.; Rice, T.W. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Selection by Multidisciplinary Consensus: The ECMO Council. ASAIO J. 2023, 69, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. ECLS registry report, international summary 2022. Available online: https://www.elso.org/registry/internationalsummaryandreports/internationalsummary.aspx (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Bartlett, R.H. ECMO: The next ten years. The Egyptian Journal of Critical Care Medicine 2016, 4, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescouflair, T.; Figura, R.; Tran, A.; Kilic, A. Adult veno-arterial extracorporeal life support. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, S1811–S1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, J.E.; Bartnikowski, N.; Bahr, V. von; Malfertheiner, M.V.; Obonyo, N.G.; Belliato, M.; Suen, J.Y.; Combes, A.; McAuley, D.F.; Lorusso, R.; et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a systematic review of pre-clinical models. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2019, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, F.; Amanvermez Senarslan, D.; Yersel, S.; Bayram, B.; Taneli, F.; Tetik, O. Systemic inflammatory response during cardiopulmonary bypass: Axial flow versus radial flow oxygenators. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2022, 45, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungatscher, A.; Tessari, M.; Stranieri, C.; Solani, E.; Linardi, D.; Milani, E.; Montresor, A.; Merigo, F.; Salvetti, B.; Menon, T.; et al. Oxygenator Is the Main Responsible for Leukocyte Activation in Experimental Model of Extracorporeal Circulation: A Cautionary Tale. Mediators Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 484979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballaux, P.K.; Gourlay, T.; Ratnatunga, C.P.; Taylor, K.M. A literature review of cardiopulmonary bypass models for rats. Perfusion 1999, 14, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, M.; Clément, D.; Stadelmann, M.; Kistler, M.; Boone, Y.; Carrel, T.P.; Tevaearai, H.T.; Longnus, S.L. Development of an ultra mini-oxygenator for use in low-volume, buffer-perfused preparations. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2012, 35, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarska, I.V.; Henning, R.H.; Buikema, H.; Bouma, H.R.; Houwertjes, M.C.; Mungroop, H.; Struys, M.M.R.F.; Absalom, A.R.; Epema, A.H. Troubleshooting the rat model of cardiopulmonary bypass: effects of avoiding blood transfusion on long-term survival, inflammation and organ damage. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2013, 67, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungwirth, B.; Lange, F. de. Animal models of cardiopulmonary bypass: development, applications, and impact. Semin. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2010, 14, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umei, N.; Lai, A.; Miller, J.; Shin, S.; Roberts, K.; Ai Qatarneh, S.; Ichiba, S.; Sakamoto, A.; Cook, K.E. Establishment and evaluation of a rat model of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) thrombosis using a 3D-printed mock-oxygenator. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evseev, A.K.; Zhuravel, S.V.; Alentiev, A.Y.; Goroncharovskaya, I.V.; Petrikov, S.S. Membranes in Extracorporeal Blood Oxygenation Technology. Membr. Membr. Technol. 2019, 1, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, S.R.; Murphree, C.R.; Zonies, D.; Meyer, A.D.; Mccarty, O.J.T.; Deloughery, T.G.; Shatzel, J.J. Thrombosis and Bleeding in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) Without Anticoagulation: A Systematic Review. ASAIO J. 2021, 67, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Sumikura, H.; Nagahama, D. Establishment of a novel miniature veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation model in the rat. Artif. Organs 2021, 45, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, T.; Sumikura, H.; Fujii, Y.; Arafune, T.; Ohgoe, Y.; Yaguchi, T.; Homma, A. Fundamental Examination of an Extracapillary Blood Flow Type Oxygenator for Extracorporeal Circulation Model of a Rat. Journal of Life Support Engineering 2018, 30, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 7199:2020-10: Kardiovaskuläre Implantate und künstliche Organe - Blut-Gas-Austauscher (Oxygenatoren), 2020-10; Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, 11.040.40. Available online: https://www.beuth.de/de/norm/din-en-iso-7199/317329787.

- XiJing Medical. Xi'an xijing medical appliance co.,ltd of product catalogue 2022.10 - Membrane oxygenator for animal experiments. Available online: https://www.alibaba.com/product-detail/Membrane-oxygenator-for-animal-experiments_62468042966.html?spm=a2700.shop_index.74.6.3c5e1627VqckuQ (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Living Systems Instruments. Gas Exchange Oxygenator, Miniature. Available online: https://livingsys.com/product/miniature-gas-exchange-oxygenator/ (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Ali, A.A.; Downey, P.; Singh, G.; Qi, W.; George, I.; Takayama, H.; Kirtane, A.; Krishnan, P.; Zalewski, A.; Freed, D.; et al. Rat model of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichter, A.M.; Ritschl, L.M.; Borgmann, A.; Humbs, M.; Luppa, P.B.; Wolff, K.-D.; Mücke, T. Development of an Extracorporeal Perfusion Device for Small Animal Free Flaps. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0147755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warenits, A.-M.; Sterz, F.; Schober, A.; Ettl, F.; Magnet, I.A.M.; Högler, S.; Teubenbacher, U.; Grassmann, D.; Wagner, M.; Janata, A.; et al. Reduction of Serious Adverse Events Demanding Study Exclusion in Model Development: Extracorporeal Life Support Resuscitation of Ventricular Fibrillation Cardiac Arrest in Rats. Shock 2016, 46, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegmann, B.; Seggern, H. von; Höffler, K.; Korossis, S.; Dipresa, D.; Pflaum, M.; Schmeckebier, S.; Seume, J.; Haverich, A. Developing a biohybrid lung - sufficient endothelialization of poly-4-methly-1-pentene gas exchange hollow-fiber membranes. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2016, 60, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnet, I.A.M.; Ettl, F.; Schober, A.; Warenits, A.-M.; Grassmann, D.; Wagner, M.; Schriefl, C.; Clodi, C.; Teubenbacher, U.; Högler, S.; et al. Extracorporeal Life Support Increases Survival After Prolonged Ventricular Fibrillation Cardiac Arrest in the Rat. Shock 2017, 48, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.-W.; Luo, C.-M.; Yu, H.-Y.; Chen, Y.-S.; Wang, C.-H. Investigation of the pathophysiology of cardiopulmonary bypass using rodent extracorporeal life support model. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2017, 17, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrahimov, N.; Natanov, R.; Boyle, E.C.; Goecke, T.; Knöfel, A.-K.; Irkha, V.; Solovieva, A.; Höffler, K.; Maus, U.; Kühn, C.; et al. Cardiopulmonary Bypass in a Mouse Model: A Novel Approach. J. Vis. Exp. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrahimov, N.; Boyle, E.C.; Gueler, F.; Goecke, T.; Knöfel, A.-K.; Irkha, V.; Maegel, L.; Höffler, K.; Natanov, R.; Ismail, I.; et al. Novel mouse model of cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 53, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrahimov, N.; Khalikov, A.; Boyle, E.C.; Natanov, R.; Knoefel, A.-K.; Siemeni, T.; Hoeffler, K.; Haverich, A.; Maus, U.; Kuehn, C. Veno-Venous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in a Mouse. J. Vis. Exp. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natanov, R.; Khalikov, A.; Gueler, F.; Maus, U.; Boyle, E.C.; Haverich, A.; Kühn, C.; Madrahimov, N. Four hours of veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation using bi-caval cannulation affects kidney function and induces moderate lung damage in a mouse model. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2019, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, A.G.; Sen, A.; Cove, M.E.; Kellum, J.A.; Federspiel, W.J. Extracorporeal CO2 removal by hemodialysis: in vitro model and feasibility. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2017, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.L.; Hackbarth, R.; Bunchman, T.E.; Blowey, D.; and Brophy, P.D. Evaluation of the PRISMA M10® Circuit in Critically Ill Infants with Acute Kidney Injury: A Report from the Prospective Pediatric CRRT Registry Group. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Moriyama, K.; Ledebo, I. AN69: Evolution of the world's first high permeability membrane. Contrib. Nephrol. 2011, 173, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, L.H.; Kellum, J.A.; Federspiel, W.J.; Cove, M.E. Carbon dioxide removal using low bicarbonate dialysis in rodents. Perfusion 2019, 34, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollborn, J.; Siemering, S.; Steiger, C.; Buerkle, H.; Goebel, U.; Schick, M.A. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition reduces ECLS-induced vascular permeability and improves microcirculation in a rodent model of extracorporeal resuscitation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2019, 316, H751–H761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Tatsumi, E.; Nakamura, F.; Oite, T. PaO2 greater than 300 mmHg promotes an inflammatory response during extracorporeal circulation in a rat extracorporeal membrane oxygenation model. J. Thorac. Dis. 2020, 12, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, G.-H.; Xu, B.; Wang, C.-T.; Qian, J.-J.; Liu, H.; Huang, G.; Jing, H. A rat model of cardiopulmonary bypass with excellent survival. J. Surg. Res. 2005, 123, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinger, F.; Schneck, E.; Schulte, C.; Gehron, J.; Mueller, S.; Sander, M.; Koch, C. Comparison of the effect of membrane sizes and fibre arrangements of two membrane oxygenators on the inflammatory response, oxygenation and decarboxylation in a rat model of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2020, 20, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbs, J.; Kong, X.-D.; Middendorp, S.J.; Prince, R.; Cooke, A.; Demarest, C.T.; Abdelhafez, M.M.; Roberts, K.; Umei, N.; Gonschorek, P.; et al. Cyclic peptide FXII inhibitor provides safe anticoagulation in a thrombosis model and in artificial lungs. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhai, K.; Wang, W.; Liu, D.; Gao, B. Establishment of a venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a rat model of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Perfusion 2021, 38, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-J.; Kayumov, M.; Kim, D.; Lee, K.; Onyekachi, F.O.; Jeung, K.-W.; Kim, Y.; Suen, J.Y.; Fraser, J.F.; Jeong, I.-S. Acute Immune Response in Venoarterial and Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Models of Rats. ASAIO J. 2021, 67, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinger, F.; Schmitt, C.; Koch, C.; McIntosh, J.M.; Janciauskiene, S.; Markmann, M.; Sander, M.; Padberg, W.; Grau, V. Application of alpha1-antitrypsin in a rat model of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, K.; Cabrales, P. Extracorporeal circulation impairs microcirculation perfusion and organ function. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2022, 132, 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greite, R.; Störmer, J.; Gueler, F.; Khalikov, R.; Haverich, A.; Kühn, C.; Madrahimov, N.; Natanov, R. Different Acute Kidney Injury Patterns after Renal Ischemia Reperfusion Injury and Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhai, K.; Li, J.; Yao, M.; Wei, S.; Cheng, X.; Yang, J.; Gao, B.; Wu, X.; et al. Venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation promotes alveolar epithelial recovery by activating Hippo/YAP signaling after lung injury. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2022, 41, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhai, K.; Huang, J.; Wei, S.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Gao, B. Sevoflurane alleviates lung injury and inflammatory response compared with propofol in a rat model of VV ECMO. Perfusion 2022, 2676591221131217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinger, F.; Schneck, E.; Schulte, C.; Schmidt, G.; Gehron, J.; Sander, M.; Koch, C. Impact of the inspiratory oxygen fraction on the cardiac output during jugulo-femoral venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the rat. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharnaf, M.; Hogue, S.; Wilkes, Z.; Reagor, J.A.; Leino, D.G.; Gourley, B.; Rosenfeldt, L.; Ma, Q.; Devarajan, P.; Palumbo, J.S.; et al. A Murine Model of Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2022, 68, e243–e250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabdullh, H.A.; Pflaum, M.; Mälzer, M.; Kipp, M.; Naghilouy-Hidaji, H.; Adam, D.; Kühn, C.; Natanov, R.; Niehaus, A.; Haverich, A.; et al. Biohybrid lung Development: Towards Complete Endothelialization of an Assembled Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenator. Bioengineering (Basel) 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, T.G.; Tipton, C.M.; Wilson, N.C.; Oppliger, R.A.; Gisolfi, C.V. Maximum oxygen consumption of rats and its changes with various experimental procedures.

- Brands, M.W.; Lee, W.F.; Keen, H.L.; Alonso-Galicia, M.; Zappe, D.H.; Hall, J.E. Cardiac output and renal function during insulin hypertension in Sprague-Dawley rats.

- Probst, R.J.; Lim, J.M.; Bird, D.N.; Pole, G.L.; Sato, A.K.; Claybaugh, J.R. Gender Differences in the Blood Volume of Conscious Sprague-Dawley Rats. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 2006, 45, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.G. Laboratory Animal Medicine, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Science & Technology: San Diego, 2015; ISBN 9780124095274. [Google Scholar]

- The laboratory rabbit, guinea pig, hamster, and other rodents; Suckow, M.A.; Stevens, K.A.; Wilson, R.P., Eds., 1st ed.; Elsevier: London, 2012, ISBN 978-0-12-380920-9.

- Barbee, R.W.; Perry, B.D.; Re, R.N.; Murgo, J.P. Microsphere and dilution techniques for the determination of blood flows and volumes in conscious mice. American Journal of Physiology 1992, 263, 728–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, P.R. Oxygen consumption in several small wild mammals. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 1948, 31, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesenberry, K.E.; Carpenter, J.W. Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents; Elsevier (Saunders): Philadelphia, 2012; ISBN 9781416066217. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrales, P.; Acero, C.; Intaglietta, M.; Tsai, A.G. Measurement of the cardiac output in small animals by thermodilution. Microvasc. Res. 2003, 66, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, P.L.; Dittmer, D.S. Biological Handbooks: Respiration and circulation, 1971, ISBN 9780913822050.

- Ross, B.; McIntosh, M.; Rodaros, D.; Hébert, T.E.; Rohlicek, C.V. Systemic arterial pressure at maturity in rats following chronic hypoxia in early life. Am. J. Hypertens. 2010, 23, 1228–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drożdż, D.; A. Gorecki. Oxygen Consumption and Heat Production in Chinchillas. Acta Theriologica 1987, 81–86.

- Hesselmann, F.; Scherenberg, N.; Bongartz, P.; Djeljadini, S.; Wessling, M.; Cornelissen, C.; Schmitz-Rode, T.; Steinseifer, U.; Jansen, S.V.; Arens, J. Structure-dependent gas transfer performance of 3D-membranes for artificial membrane lungs. Journal of Membrane Science 2021, 634, 119371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaesler, A.; Rosen, M.; Schlanstein, P.C.; Wagner, G.; Groß-Hardt, S.; Schmitz-Rode, T.; Steinseifer, U.; Arens, J. How Computational Modeling can Help to Predict Gas Transfer in Artificial Lungs Early in the Design Process. ASAIO J. 2020, 66, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arens, J.; Schraven, L.; Kaesler, A.; Flege, C.; Schmitz-Rode, T.; Rossaint, R.; Steinseifer, U.; Kopp, R. Development and evaluation of a variable, miniaturized oxygenator for various test methods. Artif. Organs 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesselmann, F.; Focke, J.M.; Schlanstein, P.C.; Steuer, N.B.; Kaesler, A.; Reinartz, S.D.; Schmitz-Rode, T.; Steinseifer, U.; Jansen, S.V.; Arens, J. Introducing 3D-potting: a novel production process for artificial membrane lungs with superior blood flow design. Bio-des. Manuf. 2022, 5, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannidis, C.; Joost, T.; Strassmann, S.; Weber-Carstens, S.; Combes, A.; Windisch, W.; Brodie, D. Safety and Efficacy of a Novel Pneumatically Driven Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Device. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2020, 109, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; He, J.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Z. Modification strategies to improve the membrane hemocompatibility in extracorporeal membrane oxygenator (ECMO). Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2021, 4, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maul, T.M.; Massicotte, M.P.; Wearden, P.D. ECMO Biocompatibility: Surface Coatings, Anticoagulation, and Coagulation Monitoring. In Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Advances in Therapy; Firstenberg, M.S., Ed.; InTech, 2016, ISBN 978-953-51-2552-5.

- Alentiev, A.Y.; Bogdanova, Y.G.; v. d. Dolzhikova; Belov, N.A.; Nikiforov, R.Y.; Alentiev, D.A.; Karpov, G.O.; Bermeshev, M.V.; Borovkova, N.V.; Evseev, A.K.; et al. The Evaluation of the Hemocompatibility of Polymer Membrane Materials for Blood Oxygenation. Membr. Membr. Technol. 2020, 2, 368–382. [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Song, Y.; Yi, E.; Duy Nguyen, B.T.; Han, D.; Sohn, E.; Park, Y.; Jung, J.; Lee, Y.M.; Cho, Y.H.; et al. Blood Oxygenation Using Fluoropolymer-Based Artificial Lung Membranes. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 6424–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ontaneda, A.; Annich, G.M. Novel Surfaces in Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Circuits. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2018, 5, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajkowski, E.F.; Herrera, G.; Hatton, L.; Velia Antonini, M.; Vercaemst, L.; Cooley, E. ELSO Guidelines for Adult and Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Circuits. ASAIO J. 2022, 68, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Requirement | Design target |

|---|---|

| State of the art design | The oxygenator is built using state-of-the-art design principles. The basic functions are scaled-down from commercially available oxygenators. |

| Interchangeable fiber type | All available and similar hollow fiber membrane types can be used. |

| Effective gas transfer | Based on a rodent body weight of 280 g and a (resting) O2 demand of 0.028 mlO2 per gram body weight per minute (Sprague-Dawley rats, both parameters published by Bedfort et al. already in 1979 [50]), the maximum oxygen transfer capacity of the rodent oxygenator should be at a minimum of 7.9 mlO2/min. This is valid at a blood flow value similar to the physiologic cardiac output (121 ml/min, for a 350 g Sprague-Dawley rat, published by Brands et al. [51] translates to approximately 100 ml/min for a 280 g rat, assuming validity of a linear interpolation). |

| Variable gas exchange surface | The oxygenator design allows for using differently large fiber modules for different animal models and ECLS modalities. The surface size is between 10 cm² for experimental incubation with scarce endothelial cells (25 % of the surface area seeded in a specifically designed incubator by Wiegmann et al. [24]) and sufficient gas transfer exchange area to allow the targeted 7.9 mlO2/min of transfer. |

| Low priming volume | Static priming volume is as low as possible to keep hemodilution low. The gas exchange surface is adjustable to keep the variable priming volume low (see above). The blood volume of a 280 g Sprague-Dawley rat can be estimated to be 20,44 ml [52]. Depending on the model, a hemodilution of 20-30 % can be tolerated, which translates to approximately 5-9 ml maximum priming volume. |

| Low pressure loss | To avoid the need of large pumps and to allow for arteriovenous ECLS cannulation, the pressure differential due to flow resistance over the oxygenator does not exceed 25 % of the average mean arterial pressure of the animal, analog to full sized oxygenators in humans. In the Sprague-Dawley rat, this means a tolerable pressure drop of 25 mmHg. |

| Hemocompatibility | Blood leading components of the oxygenator do not cause avoidable hemocompatibility issues and undesired influences for hemocompatibility testing. |

| Transparent housing | The oxygenator is designed to allow spotting of air bubbles and plasma leakage, using transparent materials where necessary. |

| Reusable housing and removable fiber bundle | To decrease economic burden and to increase availability, the oxygenator design allows non-destructive disassembly, e.g. without adhesives. All blood-leading materials are made from sterilizable materials. The (disposable) fiber bundle can be explanted and mechanically opened for visual inspection (e.g. immunofluorescence, microscopy). |

| Reproducibility, cross-lab usability and manufacturability | The oxygenator manufacturing and assembly process is simple and yields highly reproducible oxygenators. Fabrication and deployment of the oxygenator does not require any special equipment. The manufacturing process uses low-tech equipment so that other laboratories and working groups can produce test objects on their own. If other working groups do not possess sufficient equipment or resources, the oxygenator can be produced by collaborating institutions. This allows the reproduction of results as well as cross-study data interpretation, despite the large influence the oxygenator unit has on physiologic systems like hemostasis/thrombosis or inflammatory response [8]. |

| Rodent | Bodyweight (g) |

Blood volume (ml/kg) |

Hgb (g/dl) |

Hct (%) |

Gas demand O2 (l/kg/h) |

Heart rate (min-1) |

Mean art. pressure (mmHg) |

Cardiac index (ml/min/kg) |

Ref. | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse (C3H/HeJ,C57BL/6) | 30±5 | 80±4 | 14±2 (a) | 45±7(a) | 3.5±1.5(b) | 652±25 | 92±3 | 591±49 | [28,29,30,54,55,56] |

(a) Deer Mouse (b) Approximation for 6 mouse species based on data from [56]. |

| Gerbil | 89±43 | 73±12 | 14±4 | 44±8 | N/A | 430±170 | 89±11 | N/A | [54,57] | |

| Golden Syrian Hamster | 100±40 | 73±7 (c) | 15±5(d) | 45±15(d) | 2.2±0.9 (e) | 390±110 | 113±12 | 197.0±19 | [43,54,58,59] |

(c) listed in [57] without specified hamster strain (d) listed in [54] without specified hamster strain (e) Gas demand decreasing distinctly with age (11-70 days) |

| Sprague Dawley rat | 410±190 | 58±2 | 15±2(f) | 50±3(g) | 1.7±0.1(h) | 378±64 | 105±20 | 345±20(i) | [23,40,50,52,54,55,60] |

(f) Values for rat strains Kangaroo rat and Cotton rat, in [54] (g) Values for rat strains Kangaroo rat, listed in [54] (h) calculated from values of 280 g bodyweight animals (i) calculated from values of 350 g bodyweight animals |

| Chinchilla | 500±100 | 57±24(j) | 12±3 | 43±12 | 0.7±0.1 | 125±25 | N/A | N/A | [54,57,61] | (j) Estimate from absolute values listed in [54] |

| Guinea Pig | 950±250 | 80±13 | 14±3 | 40±10 | 0.8±0.04 | 395±75 | 67±3 | 270±30 | [53,54,57] |

| Blood flow (ml/min) |

Aachen (55 layers) |

Twente (56 layers) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen transfer (ml/min) |

Carbon dioxide transfer (ml/min) |

Oxygen transfer (ml/min) |

Carbon dioxide transfer (ml/min) |

||

| 60 | 3.88 | -3.76 | 4.30±0.41 | -4.97±1.10 | |

| 80 | 4.59 | -4.64 | N/A | N/A | |

| 90 | 5.04 | -5.25 | N/A | N/A | |

| 100 | 5.53 | -5.50 | 6.27±0.98 | -8.20±1.97 | |

| 140 | N/A | N/A | 8.83±1.77 | -8.64±3.50 | |

| 180 | N/A | N/A | 9.33±0.73 | -10.28±3.37 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).