1. Introduction

The world demand of energy is rising mainly due to an increase of the world population and a more energy intensive industrial sector. The depletion of fossil fuel resources and the harmful effects of burning them for energy such as climate change (Sadeghi, 2022) [

1] has prompted the development of renewable and clean sources of energy such as solar energy.

Worldwide, photovoltaic energy has grown exponentially thanks to the integration of photovoltaic panels on existing buildings but also by occupying agricultural land. Initially they were the photovoltaic fields: more or less vast expanses of solar panels on the ground, that in fact subtracted land for agriculture or grazing (Nonhebel, 2005) [

2]. But, in recent years, research has produced a new form of combination between photovoltaics and agriculture, called agrivoltaic (AV) (or agrovoltaic, or agrophotovoltaic), in which the solar collectors are placed at a height of 2-5 meters above the ground, creating a virtuous synergy between energy and agricultural production (Agostini et al., 2021) [

3]. The concept of the AV was initially proposed in the1982 by Goetzberger and Zastrow [

4], but it took about three decades until this concept was implemented in various projects and pilot plants worldwide (Weselek et al., 2019) [

5].

Over time, the technical characteristics of AV systems have been improved by passing from the application of fixed photovoltaic modules (vertical, horizontal, inclined) to dynamic ones (single and biaxial tracking systems), optimizing electricity generation and also increasing solar radiation at plant level compared to fixed modules (Valle et al., 2017) [

6]. With 1-axial tracking photovoltaics, the modules track the sun horizontally according to the angle of incidence (elevation) or vertically according to the orbit of the sun (azimuth). Biaxial trackers do both while maximizing energy yield.

Although the AV technology is increasingly being applied all over the world, there is very little accompanying scientific research to examine its impacts on agronomic parameters, such as crop performance and crop yields (Lee et al., 2022) [

7]. Some studies (Marrou et al., 2013a and b, Ravi et al., 2016, Amaducci et al., 2018) [

8,

9,

10,

11] indicate that the presence of the photovoltaic panels creates, especially in semi-arid and arid regions, a microclimate (temperature and humidity) favorable for plant growth, which can improve the performance of some crops that often suffer from the adverse effects of high solar radiation and concomitant water losses. Indeed, AV systems can bring various synergistic effects such as the reduction of global radiation on crops, benefiting production and greater water savings thanks to the reduction of evapotranspiration and the negative effects of excessive radiation. In this context, however, the impact of AV has so far been studied for a small number of crops. In a field experiment (Marrou et al., 2013c) [

12] yields of different lettuce varieties grown underneath a AV ranged from 81 to 99% of control values in full sun, with some varieties even exceeding control values. In another experiment (Schindelea et al., 2020) [

13] the potato tuber yield was decreased by 38.2% in crops grown under APV compared to the conventional potato tuber yield. Lee et al. (2022) [

7] reported that the potato yield was similar in the AV system and the control plot, on the other hand, the yields of sesame, soybean, and rice crops were 19%, 18–20%, and 13–30% lower than those grown in the control plot, respectively. The reduction of light resources (ranged from 25–32%) underneath the AV systems could be directly responsible for the slower growth and development of crop plants in the shade.

Also in previous studies, showed that artificial shade conditions reduced yields in maize and potatoes (Midmore et al.,1988, Kuruppuarachchi et al., 1990) [

14,

15]. Some plant species are able to grow at low light conditions (termed shade plants). They have low light compensation and saturation points. However, most plants can adapt to a range of low light conditions, inducing physiological and morphological changes in plants exposed to such conditions. In general, low light intensities induce stem elongation to overcome the shade conditions. Leaves of shaded plants increase their size and reduce their thickness and have a higher chlorophyll concentration (Ferrante and Marian. 2018) [

16]. Thus, the effects of shading must be considered when exploring potential AV conditions. In this regard, the cultivation of agricultural species underneath photovoltaic panels is possible using species that tolerate partial shading or that can take advantage of it. For example, strong lighting increases the accumulation of reserve substances, favors flowering and is suitable for potatoes, beets, cereals and fruit plants, while modest light availability is favorable for lengthening the vegetative parts of plants and, therefore, suitable for crops cultivated for the production of leaves and stems (Giardini, 1992) [

17]. The latter could be the case of medicinal plants, that could be very suitable for cultivation under a partially shaded AV system. Among the medicinal plants, an extremely interesting group of plants, capable of offering natural substances and raw materials of high quality value, is represented by the

Lamiaceae. Most of them are used as parts of plants (stems, leaves, flowers) fresh or dried (called drug) from which to extract essential oil. Therefore, the choice of medicinal herbs grown in this study fell on: sage, oregano, rosemary, lavender and thyme. Their role in recent years, in fact, has assumed increasingly diversified aspects, linked to the emergence of needs and opportunities that have promoted their development both in terms of business areas, and of new agricultural enterprises operating in this sector.

Italy, with 6,000 active companies and 24,000 hectares of cultivated land, is the 4th country in the EU in terms of Pamc surfaces (medicinal aromatic plants and condiments), after Poland, Bulgaria and France (IiSole24Ore, 2020)

Medicinal aromatic plants and condiments develop a market of enormous interest for Italy which produces 25 million kilos in over 6,000 companies involved and more than 24,000 cultivated hectares (with a 110% growth in three years), covering only 70 % of the entire national requirement.

It is estimated that the use of medicinal products amounts to a value at the wholesale stage of around 115 million euro. The potential volumes of use for an Italian production would amount to almost 18 thousand tons, equal to 73% of the total.

The sector records double-digit growth rates, managing to fully grasp the new requests that come both from the consumer side, such as greater attention to well-being, and from the side of community policies, which provide for the protection of biodiversity, sustainability, multifunctionality, as well as of course to represent a very promising market opportunity for farmers.

The best-selling products are parsley, basil, sage, rosemary, mint and wild fennel. Instead those that show the most interesting dynamics are coriander, chives, thyme and chilli pepper. In Italian organized distribution, aromatic herbs are considered a service product to complete the fruit and vegetable department and have a more limited range than in large-scale foreign distribution chains.

Given the total lack of studies on the AV cultivation of medicinal plants, the aim of this work is to evaluated the yield qualitative characteristics of six medicinal species (Salvia officinalis L., Origanum vulgare L., Rosmarinus officinalis L., Lavandula angustifolia L., Thymus citriodorus L. and Mentha spicata L.) underneath a dynamic AV system, compared with the same crops in the full sun.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. The dynamic Agrivoltaic system

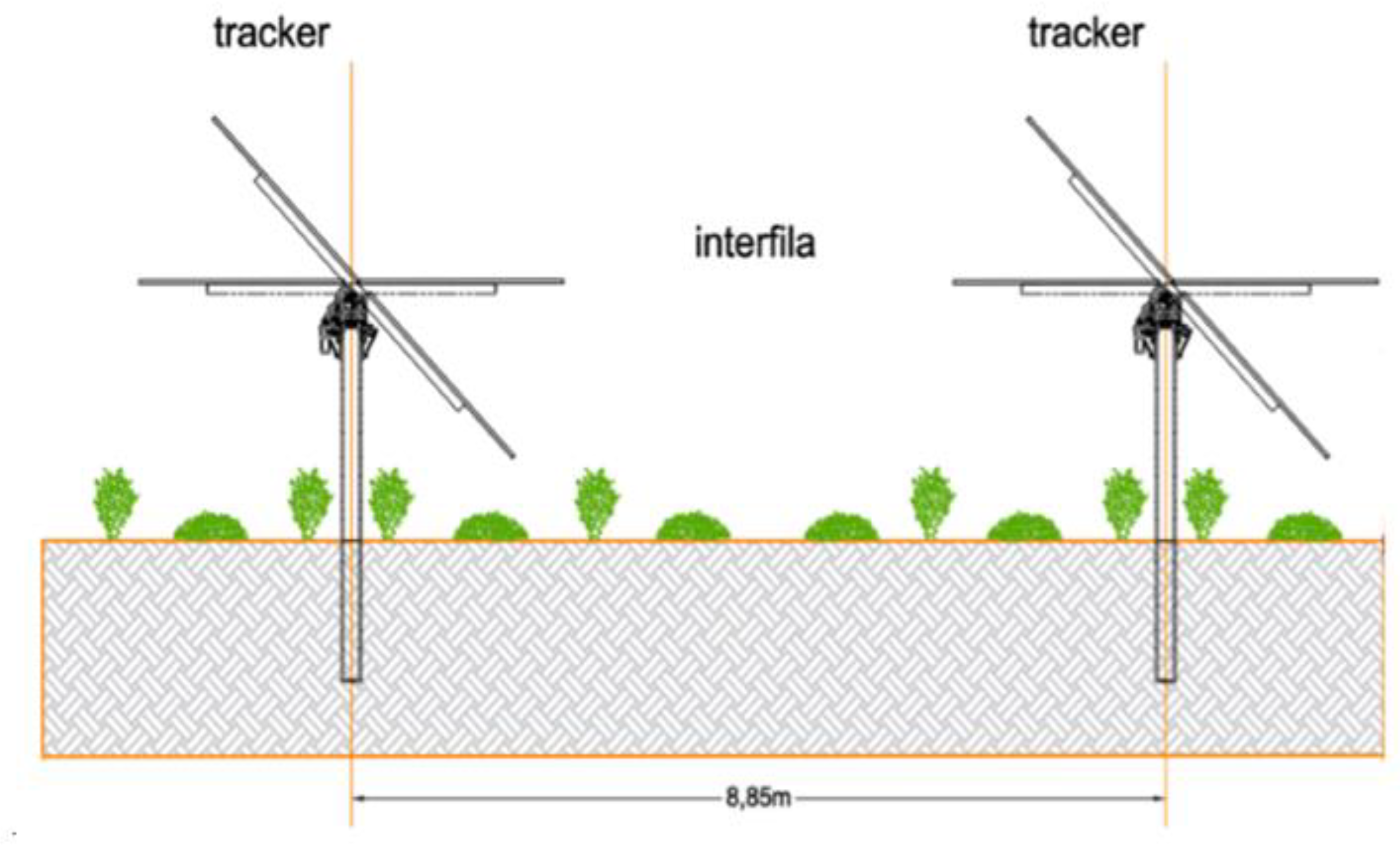

The dynamic Agrivoltaic system used in this study is the single-axis tracking photovoltaics, built on suspended structures (stilts). On the stilts are mounted horizontal main axis, on which secondary axis holding the solar panels are hinged.

The dynamic Agrivoltaic system (

Figure 1) consisting of photovoltaic solar panels (positioned 2,50 m above the crops) that can rotate in an angle of +/- 50° to adjust the level of shading.

Solar tracking system managed by an electronic unit that allows the panels to always be oriented towards the sun and avoid that they shade each other. This mechanism maximizes the photovoltaic yield and improves the availability of light.

The support structures, made of metallic material, have been arranged in a North-South direction in parallel rows and appropriately spaced apart to reduce the effects of shadows. The panels rotate on the axis from East to West, following the daily trend of Sun. The maximum angle of rotation of the modules is about 55°, while the height of the axis of rotation from the ground is equal to 2.50 m. The minimum free space between the takers, when these are arranged parallel to the ground (i.e. at midday), is 4.166 m; while when the inclination of the modules is approximately 45° the minimum height is 0.80 m.

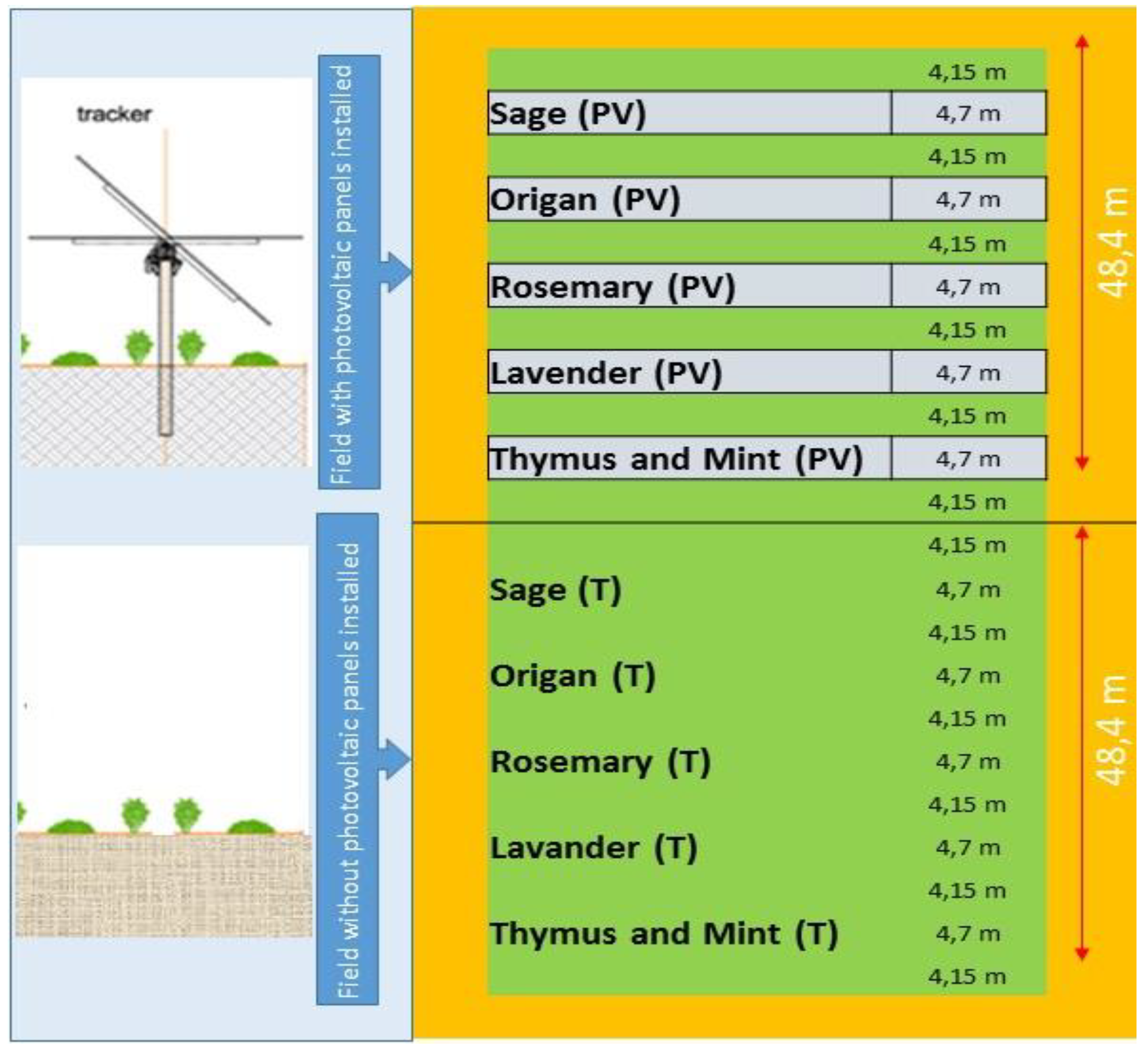

Below the dynamic agrivoltaic system, following the rotation of the solar panels, on the soil surface, two zones were distinguished: one in which it is always in the shade (indicated as UP plot), and the other in which it is alternately in the shade (indicated as BP plot). The aromatic crops grown in these two plots were compared with those grown in full sun (indicated as T plot).

2.2. Field experiment

The field experiment was carried out during 2022 season, at the countryside of San Severo (Foggia province, Apulia region, Southern Italy). The site of the research was in a typical semi-arid zone, characterized by a Mediterranean climate, classified as an “accentuated thermomediterranean” (UNESCO/FAO, 1963) [

18], with temperature that may fall below 0 °C in winter and exceed 40 °C in summer. Rainfall is unevenly distributed throughout the year and is mostly concentrated in the winter months with a long- term annual average of 559 mm (Ventrella et al. 2012) [

19].

The study was designed by the Department of Agriculture, Food, Natural resources and Engineering (DAFNE), University of Foggia and M2 Energia S.r.l., on 6 medicinal and aromatic crops: sage (

Salvia officinalis var.

latifolia L.), oregano (

Origanum vulgar L.), rosemary (

Rosmarinus officinalis L.), lavender (

Lavandula angustifolia L.), thyme (

Thymus citriodorus L.) and mint (

Mentha spicata L.). The experimental trial included the compared aromatic crops grown among the UP, BP and T plots. The soil texture was clay-loam (USDA classification) [

20], with an effective depth over 120 cm, and vertisol of alluvional origin having the following characteristics: sand = 38.6%, loam = 22.4%, clay= 39,0%; total N (Kjeldahl) = 2.7 ‰, assimilable P

2O

5 (Olsen) = 58 ppm; exchangeable K

2O (Schollemberger) = 539 ppm; Ca exchangeable = 2928 ppm; Mg exchangeable = 317 ppm; Na exchangeable = 34 ppm; ratio C/N = 5:2; electrical conductivity (ECe) = 0,63 dS cm−1; pH (in water) = 8.1; organic matter (Walkley and Black) = 2.5%. The tillage system was: 40 cm plowing depth and two treatments with disk harrow.

Figure 2.

Dynamic agrivoltaic system in San Severo (FG).

Figure 2.

Dynamic agrivoltaic system in San Severo (FG).

Before the transplanting the aromatic plants, the soil was plowed to a depth of 40 cm and refined with two treatments with a disc harrow.

The field experimental trial was carried out on 30x115 m surface (3450 m2): half underneath the AV system and the other in a full sun adjacent area.

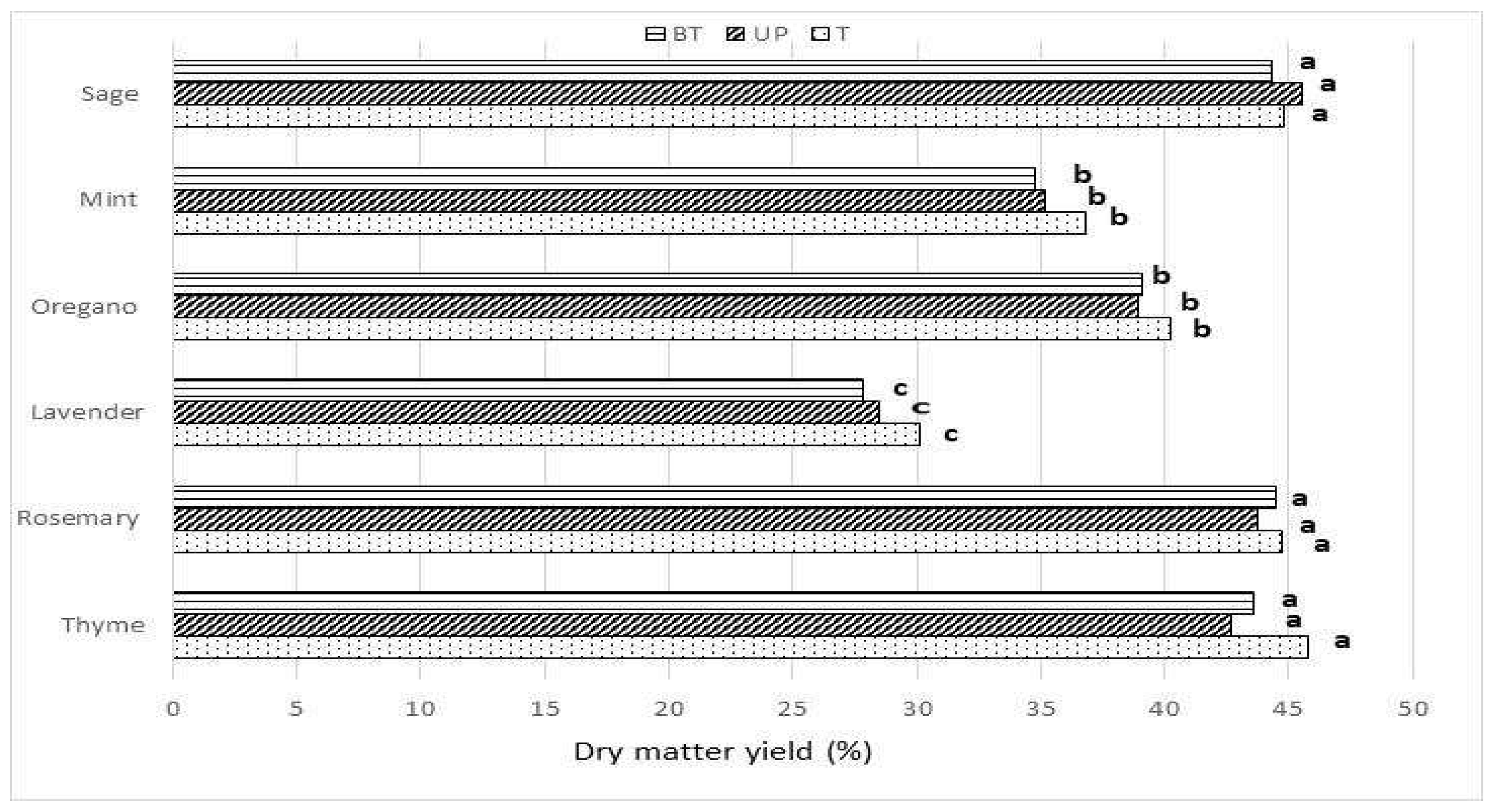

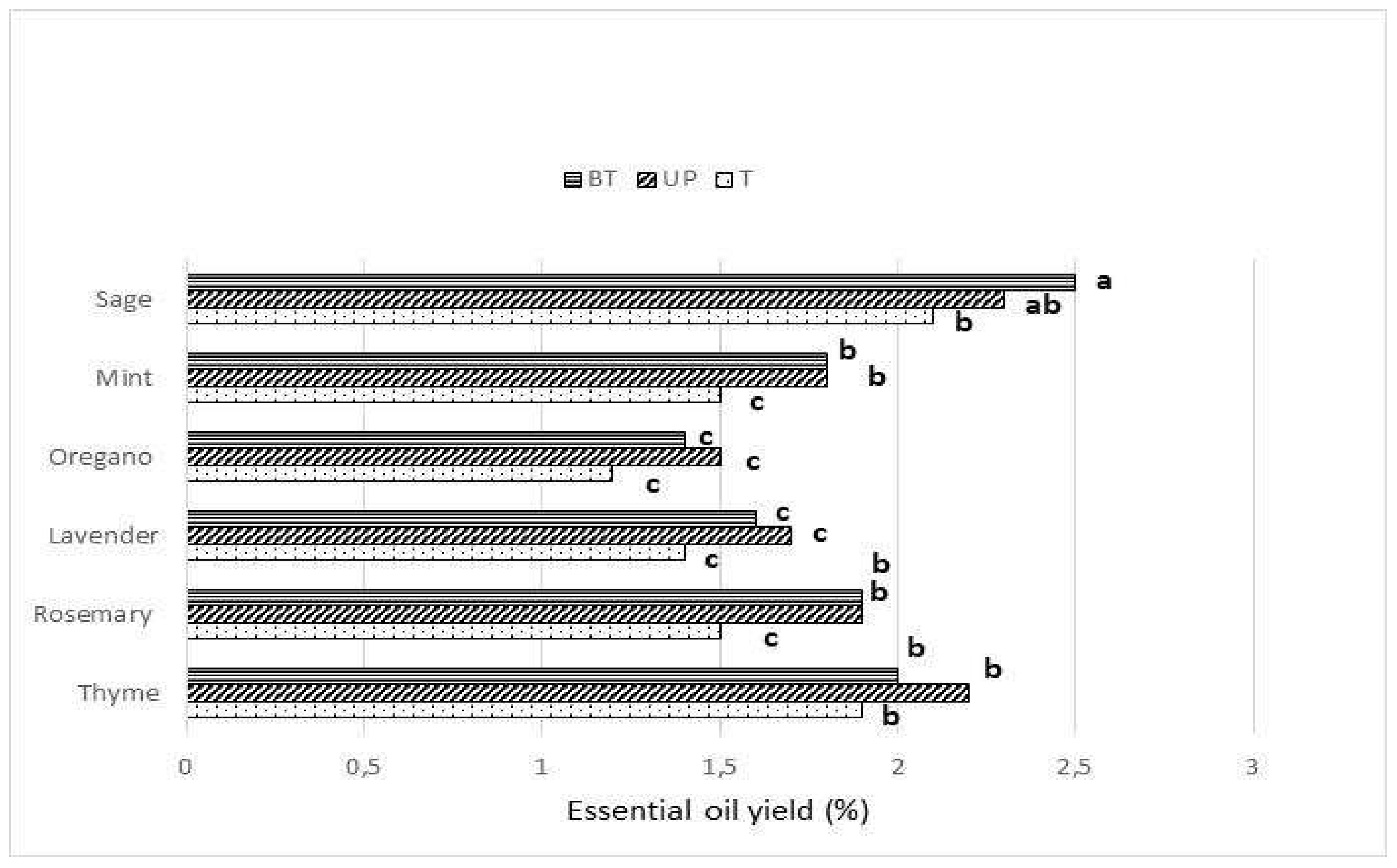

Each medicinal crop was transplanted, in continuous plant rows, 1x1m apart, on May 2022. During the growing season, drip irrigation and standard agronomic practices were applied. All the crops were harvested by hand in the balsamic phase (in July 2022). At harvest, the fresh leaves of each aromatic plants were collected, dried in an oven at 30°C, mixed for homogenization and used for essential oils (EOs) extractions by distillation for 2 hours in a current stream. The EOs yields (% of dry matter yield) were determined. EOs were isolated by direct steam distillation using a 62 L steel extractor apparatus (Albrigi Luigi EO 131, Verona, Italy). With this type of steam distillation apparatus, the remaining water (a by-product), called floral water or hydrosol, can be recycled after condensation, thereby limiting the process duration. The EOs were stored in hermetically-sealed dark-glass containers and kept in rooms at 5–6 °C.

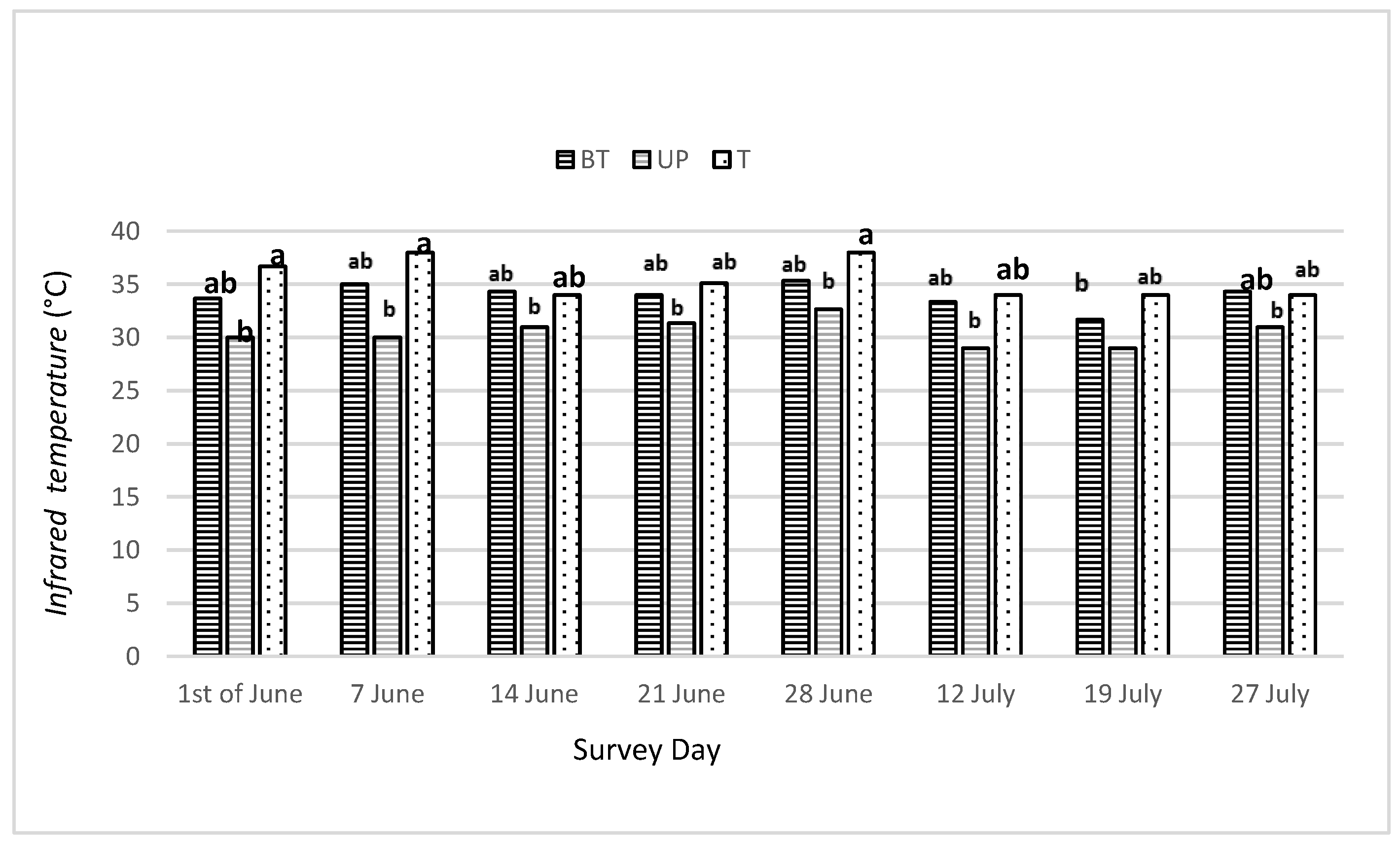

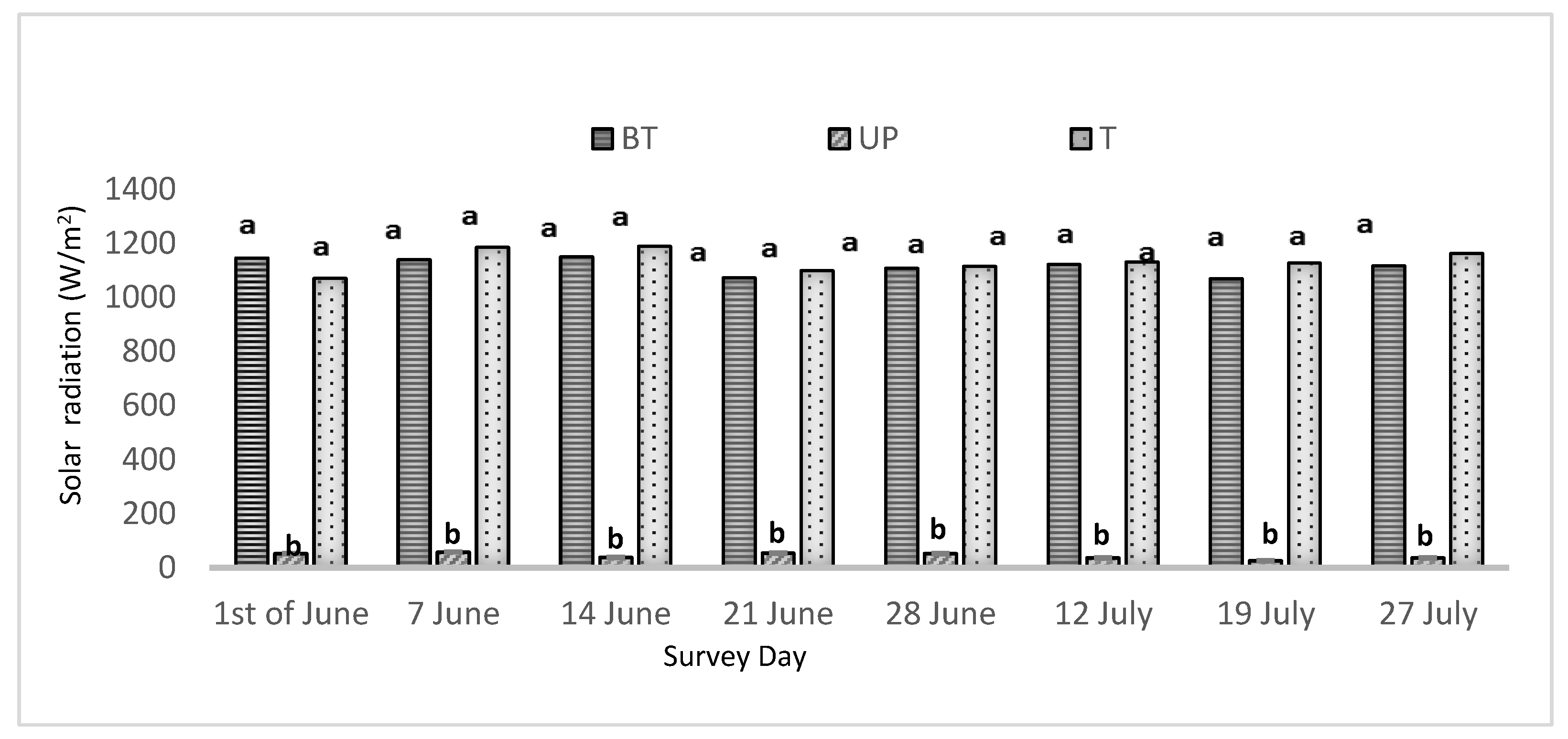

2.3. Microclimatic condition and Floristic surveys

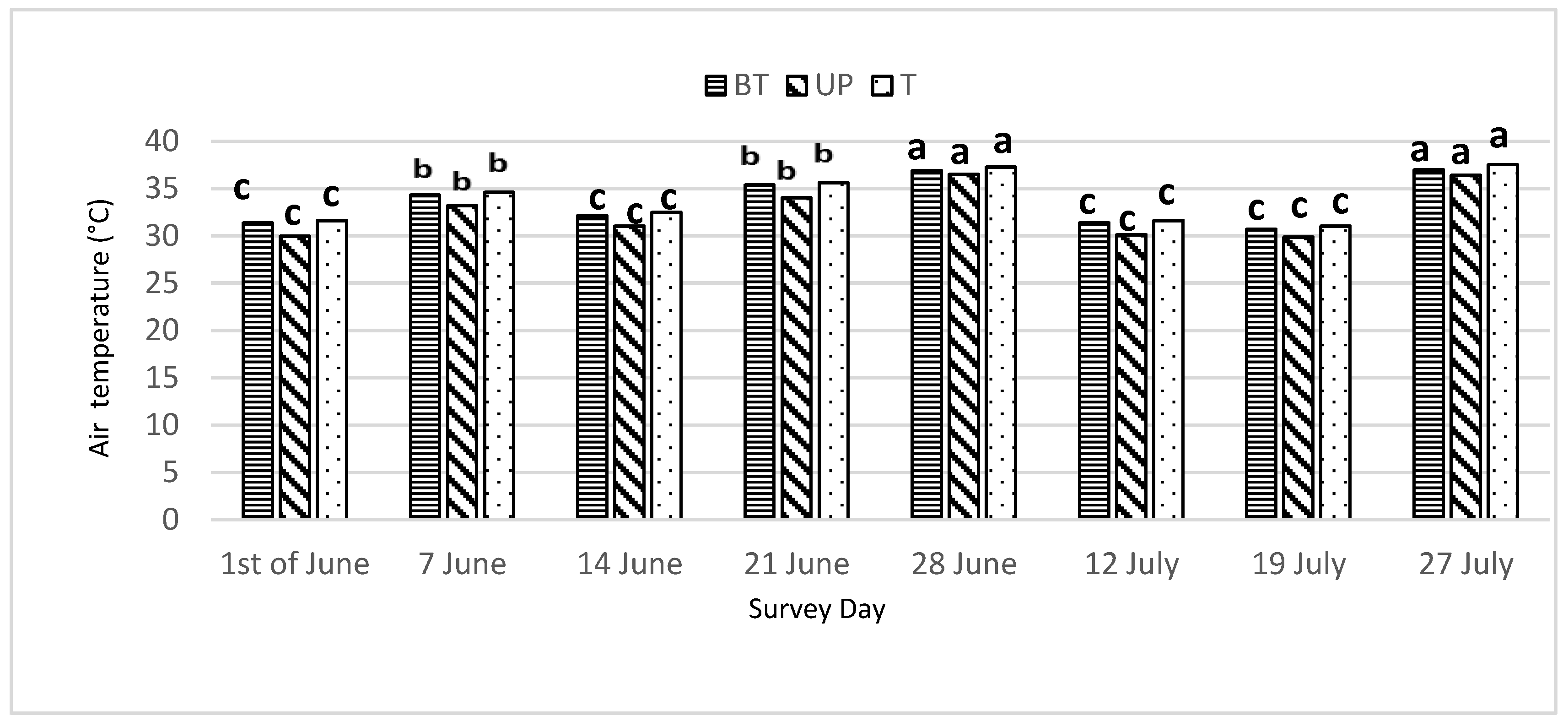

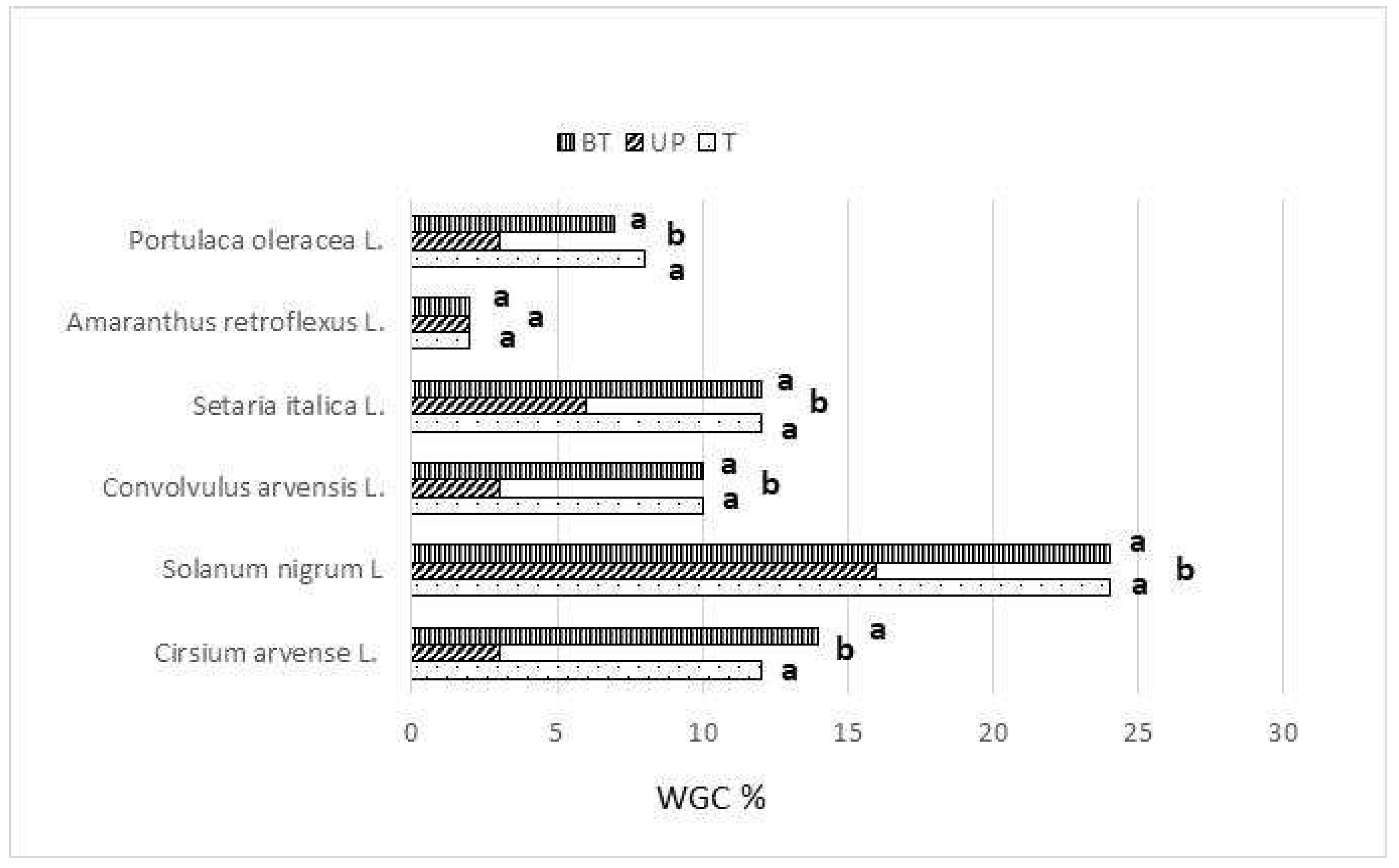

During the crop cycles of each aromatic crop, every 15 days, the solar radiation (W m2), air temperature (°C) and infrared leaf temperature (°C) in UP, BP and T plots at the hottest hours of the day (between 12 and 14), were measured. They were taken manually with solar power meter (TES, Taiwan), thermometer (TorAnn S.A.S Strumenti, Italy) and infrared thermometer (TorAnn S.A.S Strumenti, Italy), respectively. Moreover, the weed survey was carried out at harvest time. The infestation of the different weed species was manifested by the weed ground cover percentage (WGC %). The WGC % was rated visually for each weed species, according to the Braun-Blanquet (1964) cover abundance-dominance method, by assigning to each species a value ranging from 1 to 5, based on the proportion of the plot area covered. Classes of presence and abundance were transformed in cover percentage using the following scale: 0 = absent; 1 = 1–4%; 2 = 5–24%; 3 = 25–49%; 4 = 50–74%; 5 = 75–100%.

Each microclimatic parameters measurement and the floristic survey were replicated three times.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The results were evaluated with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using JMP software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and average values were compared with Tukey's test. p values < 0.05 were considered significant.