Submitted:

31 January 2023

Posted:

07 February 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Perceived stress

1.2. Social Support

1.3. Health Anxiety

1.4. Coping

1.5. Gender

1.6. Students

1.7. Lockdown

1.8. Dissociation

1.9. Aims of the study

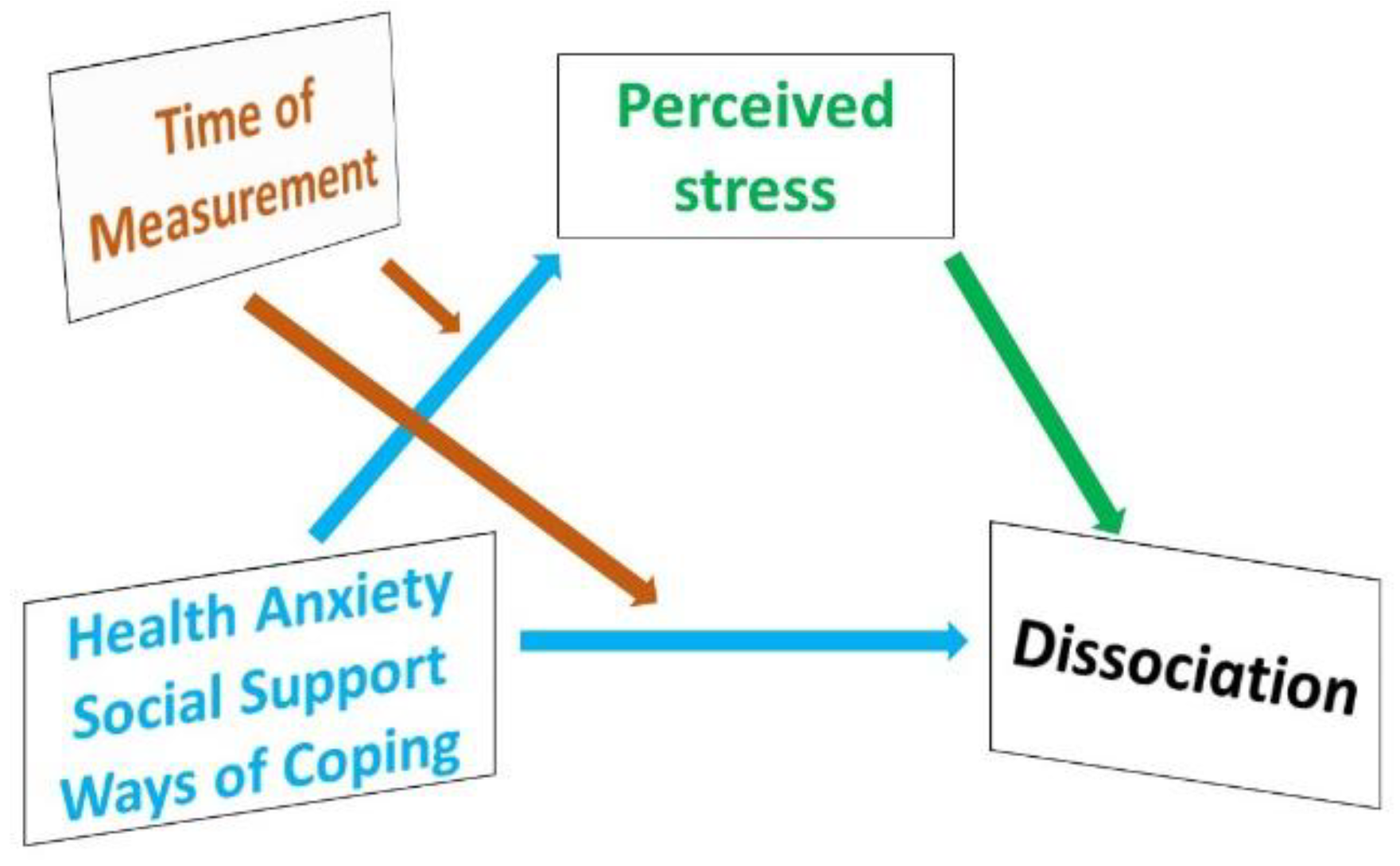

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Participants and Sampling

2.3. Survey Instruments

2.3.1. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

2.3.2. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)

2.3.3. Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI)

2.3.4. Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ)

2.3.5. The Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES)

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- About Hungary. Hungary - COVID-19. Available online: http://abouthungary.hu/coronavirus/.

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; McIntyre, R.S. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, R.P. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020, 102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vindegaard, N.; Benros, M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020, 89, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aknin, L.B.; De Neve, J.E.; Dunn, E.W.; Fancourt, D.E.; Goldberg, E.; Helliwell, J.F.; Jones, S.P.; Karam, E.; Layard, R.; Lyubomirsky, S.; Rzepa, A.; Saxena, S.; Thornton, E.M.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Whillans, A.V.; Zaki, J.; Karadag, O.; Ben Amor, Y. Mental Health During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review and Recommendations for Moving Forward. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2022, 17, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health. 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyeaka, H.; Anumudu, C.K.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Egele-Godswill, E.; Mbaegbu, P. COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci Prog. 2021, 104, 368504211019854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prati, G.; Mancini, A.D. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: a review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol Med. 2021, 51, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983, 24, 385–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchia, M.; Gathier, A.W.; Yapici-Eser, H.; Schmidt, M.V.; de Quervain, D.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Bisson, J.I.; Cryan, J.F.; Howes, O.D.; Pinto, L.; van der Wee, N.J.; Domschke, K.; Branchi, I.; Vinkers, C.H. The impact of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 22–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Syme, S.L. Social Support and Health.1st ed. Academic Press, San Fransisco, USA, 1985, pp.3-22.

- House, J.S.; Umberson, D.; Landis, K.R. Structures and processes of social support. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1988, 14, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, L.Y.; Hansel, T.C.; Bordnick, P.S. Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychol Trauma. 2020, 12, S55–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szkody, E.; Stearns, M.; Stanhope, L.; McKinney, C. Stress-Buffering Role of Social Support during COVID-19. Fam Process. 2021, 60, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Luo, S.; Mu, W.; Li, Y.; Ye, L.; Zheng, X.; Xu, B.; Ding, Y.; Ling, P.; Zhou, M.; Chen, X. Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grey, I.; Arora, T.; Thomas, J.; Saneh, A.; Tohme, P.; Abi-Habib, R. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrague, L.J.; De Los Santos, J.A.A.; Falguera, C.C. Social and emotional loneliness among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The predictive role of coping behaviors, social support, and personal resilience. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021, 57, 1578–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramowitz, J.S.; Braddock, A. Hypochondriasis and Health Anxiety. 1st ed. Hogrefe Publishing, Cambridge, USA, 2011, pp.1-9.

- Asmundson, G.J.G.; Taylor, S. How health anxiety influences responses to viral outbreaks like COVID-19: What all decision-makers, health authorities, and health care professionals need to know. J Anxiety Disord. 2020, 71, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Sutin, A.R.; Daly, M.; Jones, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J Affect Disord. 2022, 296, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus R, Folkman S, Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. 1st ed. Springer Publishing, New York, USA, 1984, pp.1-60.

- Erick, T.B. Knowledge, Attitudes, Anxiety, and Coping Strategies of Students during COVID-19 Pandemic, J Loss Trauma, 2020, 25, 635-642. [CrossRef]

- Budimir, S.; Probst, T.; Pieh, C. Coping strategies and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. J Ment Health. 2021, 30, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Liu, H.; Bai, X.W. The “psychological eye of typhoon" effect in wenchuan "5. 12" earthquake. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2009, 27, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Lei, W.; Xu, F.; Liu, H.; Yu, L. Emotional responses and coping strategies in nurses and nursing students during Covid-19 outbreak: A comparative study. PLOS One. 2020, 15, e0237303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. EJP. 1987, 1, 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, N.; Kar, B.; Kar, S. Stress and coping during COVID-19 pandemic: Result of an online survey. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashazadeh Kan, F.; Raoofi, S.; Rafiei, S.; Khani, S.; Hosseinifard, H.; Tajik, F.; Raoofi, N.; Ahmadi, S.; Aghalou, S.; Torabi, F.; Dehnad, A.; Rezaei, S.; Hosseinipalangi, Z.; Ghashghaee, A. A systematic review of the prevalence of anxiety among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2021, 293, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, S.; Biswas, P.; Ghosh, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Dubey, M.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Lahiri, D.; Lavie, C.J. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020, 14, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibaut, F.; van Wijngaarden-Cremers, P.J.M. Women's Mental Health in the Time of Covid-19 Pandemic. Front Glob Womens Health. 2020, 1, 588372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, M.; Shrestha, A.D.; Stojanac, D.; Miller, L.J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women's mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020, 23, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wen, W.; Zhang, H.; Ni, J.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Ye, L.; Feng, Z.; Ge, Z.; Luo, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W. Anxiety, depression, and stress prevalence among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Health. 2021, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharake, J.A.; Akbar, F.; Malik, A.A.; Gilliam, W.; Omer, S.B. Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 among Children and College Students: A Systematic Review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2022, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, P. Closure of Universities Due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on Education and Mental Health of Students and Academic Staff. Cureus. 2020, 12, e7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, Y.; Han, N.; Huang, H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of College Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol. 2021, 12, 669119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, K.; Vishwakarma, D.K.; Singh, N. COVID-19 and its impact on education, social life and mental health of students: A survey. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021, 121, 105866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaparounaki, C.K.; Patsali, M.E.; Mousa, D.V.; Papadopoulou, E.V.K.; Papadopoulou, K.K.K.; Fountoulakis, K.N. University students' mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, M.J.; James, R.; Magistro, D.; Donaldson, J.; Healy, L.C.; Nevill, M.; et al. Mental health and movement behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic in UK university students: Prospective cohort study. MENPA. 2020, 19, 100357. [Google Scholar]

- Sundarasen, S.; Chinna, K.; Kamaludin, K.; Nurunnabi, M.; Baloch, G.M.; Khoshaim, H.B.; Hossain, S.F.A.; Sukayt, A. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 and Lockdown among University Students in Malaysia: Implications and Policy Recommendations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commodari, E.; La Rosa, V.L.; Carnemolla, G.; Parisi, J. The psychological impact of the lockdown on Italian university students during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic: psychological experiences, health risk perceptions, distance learning, and future perspectives. MJCP, 2021, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Onyeaka, H.; Anumudu, C.K.; Al-Sharify, Z.T.; Egele-Godswill, E.; Mbaegbu, P. COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the global lockdown and its far-reaching effects. Sci Prog. 2021, 104, 368504211019854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Kolk, B.A.; van der Hart, O. Pierre Janet and the breakdown of adaptation in psychological trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1989, 146, 1530–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, E.M.; Putnam, F.W. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986, 174, 727–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabe, H.J.; Rainermann, S.; Spitzer, C.; Gänsicke, M.; Freyberger, H.J. The relationship between dimensions of alexithymia and dissociation. Psychother Psychosom. 2000, 69, 128–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, N.; Putnam, F.W.; Carlson, E.B. Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychol. Methods. 1996, 1, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, C.; Barnow, S.; Freyberger, H.J.; Grabe, H.J. Recent developments in the theory of dissociation. World Psychiatry. 2006, 5, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lynn, C.D. Adaptive and Maladaptive Dissociation: An Epidemiological and Anthropological Comparison and Proposition for an Expanded Dissociation Model. Anthropol Conscious. 2005, 16, 16–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kolk, B.A.; Fisler, R. Dissociation and the fragmentary nature of traumatic memories: overview and exploratory study. J Trauma Stress. 1995, 8, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schauer, M.; Elbert, T. Dissociation following traumatic stress: Etiology and treatment. J.Psychol. 2010, 218, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, V.L.; Gori, A.; Faraci, P.; Vicario, C.M.; Craparo, G. Traumatic Distress, Alexithymia, Dissociation, and Risk of Addiction During the First Wave of COVID-19 in Italy: Results from a Cross-sectional Online Survey on a Non-clinical Adult Sample. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022, 20, 3128–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiara, C.; Giorgio, V.; Claudio, B.; Virginia, C.; Antonio, D.C.; Carlo, L. Escaping the Reality of the Pandemic: The Role of Hopelessness and Dissociation in COVID-19 Denialism. JPM. 2022, 12, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velotti, P.; Civilla, C.; Rogier, G.; Beomonte Zobel, S. A Fear of COVID-19 and PTSD Symptoms in Pathological Personality: The Mediating Effect of Dissociation and Emotion Dysregulation. Front Psychiatry. 2021, 23, 590021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azoulay, E.; Cariou, A.; Bruneel, F.; Demoule, A.; Kouatchet, A.; Reuter, D.; Souppart, V.; Combes, A.; Klouche, K.; Argaud, L.; Barbier, F.; Jourdain, M.; Reignier, J.; Papazian, L.; Guidet, B.; Géri, G.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Guisset, O.; Labbé, V.; Mégarbane, B.; Van Der Meersch, G.; Guitton, C.; Friedman, D.; Pochard, F.; Darmon, M.; Kentish-Barnes, N. Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Peritraumatic Dissociation in Critical Care Clinicians Managing Patients with COVID-19. A Cross-Sectional Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020, 202, 1388–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daglis, T. The Increase in Addiction during COVID-19. Encyclopedia 2021, 1, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmes, P.; Brunet, A.; Benoit, M.; Defer, S.; Hatton, L.; Sztulman, H.; Schmitt, L. Validation of the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire self-report version in two samples of French-speaking individuals exposed to trauma. Eur Psychiatry. 2005, 20, 145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004, 6, e34, Erratum in: 10.2196/jmir.2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spacapan, S.; Oskamp, S. The Social Psychology of Health 1st ed. SAGE Publications, USA, 1988, pp.31-67.

- Stauder, A.; Thege, B.K. Az Észlelt Stressz Kérdőív (PSS) Magyar Verziójának Jellemzői. Mentálhig és Pszichoszomatika. 2006, 7, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsolya, P.-Z.; Zoltán, K.M.; Szilvia, J. A Multidimenzionális Észlelt Társas Támogatás Kérdőív magyar nyelvű validálása. Mentálhig És Pszichoszomatika. 2017, 18, 230–262. [Google Scholar]

- Salkovskis, P.M.; Rimes, K.A.; Warwick, H.M.C. The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002, 32, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köteles, F.; Simor, P.; Bárdos, G. Validation and psychometric evaluation of the Hungarian version of the Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI). Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika. 2011, 12, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R. S. If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. J Pers Soc Psychol, 1985, 48, 150–170. [CrossRef]

- Sørlie, T.; Sexton, H.C. The factor structure of “The Ways of Coping Questionnaire” and the process of coping in surgical patients. Pers Individ Dif. 2001, 30, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rózsa, S.; Purebl, G.; Susánszky, É.; Kő, N.; Szádóczky, E.; Réthelyi, J.; et al. Dimensions of coping: Hungarian adaptation of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Mentálhigiéné És Pszichoszomatika. 2008; 217–241. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, E.B.; Putnam, F.W. Dissociation: An update on the Dissociative Experience Scale. Univ Oregon Sch Bank 1993, 6, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dóra, P.-F.; Gyöngyi, A.; Csilla, B.; Zsófia, K.; Sarolta, K. Kérdőívek, becslőskálák a klinikai pszichológiában. 3rd ed. Semmelweis Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary.

- Alberts, N.M.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Jones, S.L.; Sharpe, D. The Short Health Anxiety Inventory: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2013, 27, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderlinden, J.; Van Dyck, R.; Vandereycken, W.; Vertommen, H. The Dissociation Questionnaire (Dis-G): development, reliability and validity of a new self-reporting Dissociation Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatr Belg 1994, 94, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chu, J.A. Rebuilding shattered lives: Treating complex PTSD and dissociative disorders, 2nd ed. US: John Wiley & Sons Inc, USA.

- Ray, S.; Ray, R.; Singh, N.; Paul, I. Dissociative experiences and health anxiety in panic disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2021, 63, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Xiong, S.; Zhang, W.; Guo, S. The Effect of Perceived Threat Avoidability of COVID-19 on Coping Strategies and Psychic Anxiety Among Chinese College Students in the Early Stage of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 3, 854698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, L.M.; Litt, D.M.; Stewart, S.H. Drinking to cope with the pandemic: The unique associations of COVID-19-related perceived threat and psychological distress to drinking behaviors in American men and women. Addict Behav. 2020, 110, 106532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle N (Australian National University, Canberra, Australia), Sollis K (Australian National University, Canberra, Australia) Determinants of participation in a longitudinal survey during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of a low-infection country, 2021.

| Factor | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||

| item4 | 0.772 | ||||||||

| item3 | 0.635 | ||||||||

| item5 | 0.499 | ||||||||

| item1 | 0.414 | ||||||||

| item15 | 0.31 | ||||||||

| item9 | 0.565 | ||||||||

| item8 | 0.551 | ||||||||

| item16 | 0.425 | ||||||||

| item10 | 0.399 | ||||||||

| item14 | 0.304 | ||||||||

| item7 | .231 | ||||||||

| item2 | 0.984 | ||||||||

| item11 | 0.68 | ||||||||

| item6 | 0.5 | ||||||||

| item13 | 0.383 | ||||||||

| item12 | 0.335 | ||||||||

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | α | ||

| DES | .00 | 100.00 | 20.374819.038) | .953 | |

| DES amnesia | .00 | 100.00 | 13.012(17.517) | .882 | |

| DES depersonalization | .00 | 100.00 | 14.859(20.687) | .871 | |

| DES absorption | .00 | 100.00 | 33.251(25.087) | .899 | |

| PSS | .00 | 4.00 | 2.287(.864) | .866 | |

| SHAI | 1.00 | 3.44 | 1.939(.439) | .864 | |

| MSPSS_others | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.683(1.937) | .926 | |

| MSPSS_family | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.939(1.704) | .902 | |

| MSPSS_friends | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.701(1.725) | .925 | |

| WCQ_wishfulthinking | .00 | 3.00 | 1.992(.703) | .750 | |

| WCQ_goal-oriented | .00 | 3.00 | 1.876(.730) | .803 | |

| WCQ_seeksupport | .00 | 3.00 | 1.325(796) | .808 | |

| WCQ_thinkover | .00 | 3.00 | 1.676(.780) | .803 | |

| WCQ_avoid | .00 | 3.00 | 1.548(.751) | .750 |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | α | |

| DES | .00 | 100.00 | 17.092(15.356) | .939 |

| DES amnesia | .00 | 85.00 | 10.259(13.720) | .830 |

| DES depersonalization | .00 | 96.00 | 10.833(16.772) | .861 |

| DES absorption | .00 | 100.00 | 30.134(21.528) | .877 |

| PSS | .07 | 4.00 | 2.129(.840) | .910 |

| SHAI | 1.00 | 4.00 | 1.929(.421) | .865 |

| MSPSS_others | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.512(.914) | .908 |

| MSPSS_family | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.82481.168) | .919 |

| MSPSS_friends | 1.00 | 5.00 | 4.126(1.101) | .935 |

| WCQ_humor | .00 | 3.00 | 1.700 (1.108) | - |

| WCQ_positive | .00 | 3.00 | 1.384(.743) | .708 |

| WCQ_distancing | .00 | 3.00 | .821(.549) | .530 |

| WCQ_outer_persepctive | .00 | 3.00 | 1.646(.702) | .606 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| 1 DES | - | ||||||||||||

| 2 DES_amnesia | ,800*** | - | |||||||||||

| 3 DES_deperson | ,856*** | ,685*** | - | ||||||||||

| 4 DES_absorption | ,936*** | ,628*** | ,701*** | - | |||||||||

| 5 Perceived stress | ,436*** | ,268*** | ,351*** | ,473*** | - | ||||||||

| 6. SHAI | ,393*** | ,253*** | ,327*** | ,423*** | ,481*** | - | |||||||

| 7. MSPSS_others | -,139** | -,059 | -,197*** | -,107* | -,199*** | -,168*** | - | ||||||

| 8. MSPSS_family | -,171*** | -,116* | -,183*** | -,155*** | -,287*** | -,220*** | ,530*** | - | |||||

| 9. MSPSS_friends | -,145*** | -,048 | -,180*** | -,119** | -,221*** | -,147*** | ,610*** | ,518*** | - | ||||

| 10. WCQ_wishfulthink | ,413*** | ,262*** | ,351*** | ,443*** | ,480*** | ,411*** | -,025 | -,107* | -,006 | - | |||

| 11. WCQ_goal-oriented | -,061 | -,005 | -,069 | -,068 | -,283*** | -,095* | ,265*** | ,279*** | ,260*** | ,165*** | - | ||

| 12. WCQ_seeksupport | -,072 | ,049 | -,061 | -,104* | -,152*** | -,048 | ,462*** | ,383*** | ,479*** | ,053 | ,427*** | - | |

| 13. WCQ_thinkover | ,106* | ,111* | ,099* | ,095* | -,145*** | ,073 | ,169*** | ,205*** | ,145*** | ,283*** | ,540*** | ,398*** | - |

| 14. WCQ_avoid | ,163*** | ,123** | ,160*** | ,125** | -,014 | -,011 | -,163*** | -,048 | -,126** | ,240*** | ,312*** | -,036 | ,293*** |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| 1 DES | - | |||||||||||

| 2 DES_amnesia | ,809*** | - | ||||||||||

| 3 DES_deperson | ,818*** | ,603*** | - | |||||||||

| 4 DES_absorption | ,952*** | ,684*** | ,682*** | - | ||||||||

| 5 Perceived stress | ,450*** | ,340*** | ,372*** | ,438*** | - | |||||||

| 6. SHAI | ,316*** | ,213*** | ,278*** | ,304*** | ,437*** | - | ||||||

| 7. MSPSS_others | -,200*** | -,185*** | -,215*** | -,159*** | -,265*** | -,124*** | - | |||||

| 8. MSPSS_family | -,285*** | -,244*** | -,245*** | -,265*** | -,395*** | -,222*** | ,526*** | - | ||||

| 9. MSPSS_friends | -,158*** | -,121*** | -,186*** | -,125*** | -,274*** | -,208*** | ,562*** | ,481*** | - | |||

| 10.WCQ_humor | -,039 | -,031 | ,008 | -,053 | -,274*** | -,210*** | ,111*** | ,153*** | ,198*** | - | ||

| 11. WCQ_positive | -,078** | -,066* | -,042 | -,070* | -,400*** | -,241*** | ,235*** | ,329*** | ,269*** | ,444*** | - | |

| 12. WCQ_distancing | ,322*** | ,240*** | ,296*** | ,307*** | ,367*** | ,247*** | -,095*** | -,153*** | -,050 | ,032 | ,002 | - |

| 13.WCQ_outer_pers | ,006 | -,005 | ,022 | ,010 | -,164*** | -,071* | ,228*** | ,200*** | ,297*** | ,259*** | ,468*** | ,137*** |

| dependent variables | independent variables |

indirect effects | direct effects | index of moderated mediation | ||

| measurement 1 | measurement 2 | measurement 1 | measurement 2 | |||

| absorption | SHAI | 3.930* (2.817; 5.253) | 4.617* (2.958; 6.441) | 5.890* (2.772; 9.008) | 7.044* (1.284; 12.083) | .687 (-1.012; 2.437) |

| MSPSS_others | -.000 (.283; -.565) | 4.617* (2.958; 6.441) | .197 (-.592; .989) | -.597 (-3.161; 1.968) | .197 (-.558; .971) | |

| MSPSS_family | -1.149* (-1.590; -.732) | -.940* (-1.5656; -.316) | -2,322* (-3.597; -1.048) | -3,902* (-5,944; -1,859) | -.209 (-.384; .836) | |

| MSPSS_friends | -.244 (-.738; .219) | -.824* (-1,486; -.165) | .627 (-.777; 2.032) | -.289 (-2,452; 1.875) | -.580 (-1.250; 0.057) | |

| WCQ_humor | -.568* (-.980; -.192) | -.967* (-1.629; -.352) | .706 (-1,439; 2.850) | .104 (-1.108; 1.316) | -.400 (-1,095; .271) | |

| WCQ_positive | -2.232* (-2.994; -1.538) | -2.470* (-3.594; -1.434) | 4.191* (2.157; 6.225) | 2.697 (-.581; 5.976) | -.238 (-1.243; .775) | |

| WCQ_distancing | 3.949* (2.954; 5.007) | 3.637* (2.386; 5.016) | 4.887* (2.407; 7.367) | 5.678* (1.725; 9.632) | -.312 (-1.540; .968) | |

| WCQ_outer_pers | .142 (-0.450; .748) | .053 (-.834; .939) | .7034 (-1.270; 2.677) | -1,856 (-5.215; 1.503) | -.089 (-1.077; .903) | |

| depersonalization | SHAI | 1.834* (1.174; 2.595) | 2.155* (1.239; 3.254) | 4.984* (2,499; 7.470) | 5.311* (.720; 9.902) | .321 (-.497; 1.167) |

| MSPSS_others | 0.000 (-.258; .271) | 0.092 (-.279; .482) | -2,042* (-3.449; -0.635) | -2,611* (-4.655; -0.567) | 0.092 (-.275; .476) | |

| MSPSS_family | -.536* (-.788; -.313) | -.438* (-.764; -.149) | -1.414* (-2.430; -.397) | -2.034* (-3.663; -0.405) | .098 (-0.188; .402) | |

| MSPSS_friends | -.114 (-0.359; .110) | -.385* (-.722;-.069) | .068 (-1.052; 1.187) | -.195 (-1.920; 1.530) | -.271 (-.606; .415) | |

| WCQ_humor | -.265* (-.479; -.084) | -.452* (-.782; -.154) | .715 (-.251; 1.681) | 1.061 (-.649; 2.770) | -.186 (-.512; .139) | |

| WCQ_positive | -1.042* (-1.493; -.637) | -1,153 (-1.783; .607) | 2,354* (.732; 3.976) | 2,115 (-.499; 4.729) | -.111 (-.608;.381) | |

| WCQ_distancing | 1.849* (1.216; 2.556) | 1.703* (1.019; 2,525) | 4,091* (2.117; 6.065) | 7.481* (4.334; 10.628) | -,146 (-.765; .464) | |

| WCQ_outer_pers | .066 (-.221; .369) | .025 (-.388; .452) | .802 (-1.200; 1.949) | 1.366 (-2.928; 2.430) | -,041 (-.515; .444) | |

| amnesia | SHAI | 1.576* (.980; 2.336) | 1,851* (1.068; 2.839) | 1,768 (-.364; 3.901) | 1.136 (-2.803; 5.075) | .275 (-.415; .986) |

| MSPSS_others | 0.000 (-.240; .226) | .079 (-.250; .406) | -0.722 (-1,928; .485) | -1.864* (-3,617; .-.111) | 0.079 (-.231; .410) | |

| MSPSS_family | -.460* (-.681; -,269) | -.377* (-.674; -.132) | -1.155* (-2.027; -2.083) | -1,993* (-3.390;-.596) | .0838 (-.167; .339) | |

| MSPSS_friends | -,097 (-0.301; 0.096) | -.328* (-.623; -.064) | .484 (-.477; 1.444) | -,341 (-1.821; 1.138) | -,231 (-0.516; .028) | |

| WCQ_humor | -.229* (-.415; -.077) | -.390* (-.694; -.133) | .183 (.665; -.646) | 1.435 (-.030; 2.901) | -.161 (-.4709; .106) | |

| WCQ_positive | -.893* (-1.296; -.543) | -.989* (-1.572; -.511) | 1.770* (.379; 3.162) | 1.211 (-1.032; 3,453) | -.095 (-.552; .326) | |

| WCQ_distancing | 1.580* (1.020; 2.215) | 1.456* (.854; 2.179) | 3.092* (1.396; 4.788) | 3.373* (.669; 6.077) | -.125 (-.667; .398) | |

| WCQ_outer_pers | .057 (-.193; .308) | .021 (-,334; .407) | -.473 (-1.824; .877) | -1.282 (-3.5809; 1.016) | -.035 (-.441; .372) | |

| Dissociation sum | SHAI | 2.447* (1.688; 3.293) | 2.875* (.582; 4.092) | 4.214* (1.989; 6.440) | 4.4969* (.386; 8.607) | .427 (-.651; 1.557) |

| MSPSS_others | -.000 (-.349; .353) | .122 (-,373; .611) | -..892 (-2.151; .368) | -1.691 (-3,52; .139) | .123 (-.358; .591) | |

| MSPSS_family | -.715* (-1.004; -.458) | -.585* (-.993; -.195) | -1.630* (-2,540; -.721) | -2.643* (-4.101; -1.185) | .130 (-.258;.536) | |

| MSPSS_friends | -.151 (-.445; .144) | -.512* (-.930; -.110) | .392 (-.609; 1.395) | -.275 (-1.819; 1.269) | -.361 (-.776; .030) | |

| WCQ_humor | -.354* (-.625; -.113) | -.603* (-1.035; -.222) | .334 (-.531; 1.199) | 1.067 (-.463; 2.598) | -.249 (-.702; .168) | |

| WCQ_positive | -1.389* (-1.900; -.935) | -1.537* (-2.268; -.868) | 2.772 (1.320; 4.224) | 2.008 (-.332; 4,348) | -.148 (-.798; .523) | |

| WCQ_distancing | 2.459* (1.787; 3.177) | 2.265* (1.467; 3.180) | 4,023* (2.254; 5,793) | 5,511* (2.690; 8.331) | -,194 (-1.009; .590) | |

| WCQ_outer_pers | .088 (-.287; .456) | .033 (-.548; .609) | .202 (-1.207; 1.611) | -1,129 (-3.527; 1,269) | -.055 (-.672; .577) | |

| dependent variables |

independent variables |

indirect effects | direct effects | index of moderated mediation | ||

| measurement 1 | measurement 2 | measurement 1 | measurement 2 | |||

| absorption | SHAI | 3.841* (1.963; 5.974) | 3.304* (1.157; 6.103) | 9.230* (3.532; 14.928) | 19.143* (10.651; 27.636) | -.537 (-2.802; 1.822) |

| MSPSS_others | .079 (-.213; .381) | -.087 (-.597; .420) | .043 (-1.376; 1,462) | .697 (-1.370; 2.765) | -.166 (-.730; .369) | |

| MSPSS_family | -.167 (-.546; .164) | -.380 (-.996; .159) | .2938 (-1.210; 1.798) | 1.300 (-.978; 3.578) | -.213 (-.836; .340) | |

| MSPSS_friends | -.420* (-.830; -.067) | -.574* (-1.254; -.018) | -.205 (-1.792; 1.382) | 1.379 (-.994; 3.752) | -.153 (-.792; .482) | |

| WCQ_wishfulthinking | 3.628* (2.010; 5.093) | 5.1169* (2.720; 7.976) | 8.604* (4.659; 12.550) | 5.835* (.524; 11.147) | 1,488* (.121; 3.353) | |

| WCQ_goal-oriented | -2.561* (-4.038; -1.299) | -.678 (-2.118;.515) | -1.765 (-5.691; 2.161) | 2.682 (-8,164; 2.377) | 1.883* (.524; 3.508) | |

| WCQ_seeksupport | .735 (-.048; 1.598) | .255 (-.791; 1.397) | -3.924* (-7.353; -.494) | 2.451 (-9,0807; .552) | -.480 (-1.749; .771) | |

| WCQ_thinkover | -1.472* (-2.597; -.622) | -.939 (-2.273; .234) | 4.187 (.694; 7.680) | 5.244 (-.014; 10.502) | .533 (-.793; 2.036) | |

| WCQ_avoid | -.087 (-.839; .722) | -.006 (-1.056; 1.219) | 3.575* (.269; 6.882) | -4.392 (-1.056; 1.219) | .081 (-1.224; 1.455) | |

| depersonalization | SHAI | 1.393* (.080; 2.913) | 1.198 * (.046; 2.888) | 6.512* (1.340; 11.683) | 3.923* (6,111; 21.527) | -.195 (-1.186; .779) |

| MSPSS_others | .029 (-.086; .161) | -.031 (-.248; .174) | -.732 (-2.019; .555) | -,394 (-2.268; 1.480) | -.060 (-.309; .151) | |

| MSPSS_family | -.060 (-.251; .051) | -.137 (-.456; .053) | .281 (-1.083; 1.645) | .771 (-1.295; 2.837) | -.077 (-.370; .132) | |

| MSPSS_friends | -.152 (-.374; .003) | -.207 (-.522; .029) | -.918 (-2.357; .521) | .054 (-2.098; 2.206) | -.055 (-.311; .206) | |

| WCQ_wishfulthinking | 1.410* (.136; 2.710) | 1.988* (.189; 3.863) | 6.189* (2.624; 9.754) | 1.139 (-3.660; 5.938) | .578 (-.010; 1.511) | |

| WCQ_goal-oriented | -.930* (-1.939; -,037) | -.246 (-1.007; .193) | -2.143 (-5.701; 1.415) | -2.963 (-7.740; 1.813) | .683 (.004; 1.578) | |

| WCQ_seeksupport | .264 (-.041; .725) | .092 (-.319; .641) | .225 (-2.883; 3.333) | 2.221 (-4.254; 4.477) | -.173 (-.763; .335) | |

| WCQ_thinkover | -.532* (-1.219; -.033) | -,339 (-.969; .103) | 2.121 (-1.045; 5,287) | 1.749 (-3,017; 6.515) | .193 (-.285; .909) | |

| WCQ_avoid | -.031 (-.358; .304) | -.002 (-.504; .474) | 4,226* (1.211; 7.240) | .258 (-4.131; 4.648) | .029 (-.552; .570) | |

| amnesia | SHAI | 1.417* (.373; 2.709) | 1.219* (.244; 2.571) | 4.507 (-.022; 9.036) | 9,654* (2.904; 16.404) | -.198 (-1.172; .684) |

| MSPSS_others | .029 (-.082; .154) | -.032 (-.237; .160) | -.135 (-1.260; .991) | -.641 (-2.280; .998) | -,061 (-.300; .136) | |

| MSPSS_family | -.061 (-.220; .055) | -.139 (-.421; .056) | .041 (-1.152; 1,235) | .053 (-1,754; 1.861) | -,077 (-.334; .133) | |

| MSPSS_friends | -.152* (-.338; -.014) | -.207 (-.487; .009) | .420 (-.839; 1.679) | -.474 (-2.357; 1.409) | -.055 (-.294; .192) | |

| WCQ_wishfulthinking | 1.401* (.454; 2.457) | 1.975* (.631; 3.547) | 2.809 (-.314; 5.931) | -.765 (-4.969; 3.439) | .575* (.015; 1.431) | |

| WCQ_goal-oriented | -.959* (-1.744; -.260) | -.254 (-.936; .179) | -1.278 (-4.390; 1.834) | -2.443 (-6.621; 1.735) | .705* (.124; 1.444) | |

| WCQ_seeksupport | .270 (-.014; .693) | .094 (-.317; .564) | 1.486 (-1.232; 4.205) | 1.407 (-2.412; 5.225) | -.177 (-.742; .266) | |

| WCQ_thinkover | -.552* (-1.146; -.119) | -,352 (-.976; .078) | 2,724 (-.043; 5,490) | .485 (-3,679; 4.650) | .200 (-.300; .836) | |

| WCQ_avoid | -.032 (-.339; .271) | -.002 (-.452; .455) | 3.633* (.992; 6.273) | 1,129 (-2,716; 4.973) | .030 (-.496; .571) | |

| Dissociation sum | SHAI | 2.217* (.998; 3.695) | 1.907* (.583; 3.790) | 6.750* (2.199; 11.300) | 14.205* (7.423; 20.987) | -.310; (-.634; 1.081) |

| MSPSS_others | -.125 (.046; .233) | -.050 (-.357; .247) | -.274 (-1.407; .859) | -,112 (-1.763; 1.538) | -.096 (-.439; .225) | |

| MSPSS_family | -,096 (-.328; .084) | -,219 (-.587; .087) | ,205 (-.995; 1,406) | .708 (-1.111; 2,527) | -,122 (-.495; .210) | |

| MSPSS_friends | -.241* (-.500; -.035) | -.330 (-.730; .005) | -.234 (-1.503; 1.034) | .320 (-1,577; 2.216) | -,088 (-.456; .300) | |

| WCQ_wishfulthinking | 2,146* (1.025; 3,424) | 3,027* (1.440; 4.886) | 5,867* (2.724; 9,011) | 2,070 (-2.162; 6.301) | .880* (.059; 1.962) | |

| WCQ_goal-oriented | -1.484* (-2.449; -.655) | -.393 (-1.330; .316) | -1.729 (-4.862; 1.405) | -2.767 (-6.973; 1.440) | 1.091* (.262; 2.098) | |

| WCQ_seeksupport | .423 (-.016; 1.009) | .147 (-.453; .869) | -,737 (-3,475; 3.000) | -.915 (-4,760; 2.929) | -.276 (-1.056; .484) | |

| WCQ_thinkover | -.852* (-1.567; -.307) | -.543 (-1.352; .141) | 3.011* (.222; 5.799) | 2.493 (-1.704; 6.690) | .309 (-.462; 1.238) | |

| WCQ_avoid | -.050 (-,496; .427) | -,003 (-.646; .706) | 3,811* (1.162; 6,460) | -1.001 (-4,858; 2.855) | ,047 (-.731; .813) | |

| dependent variables | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Perceived stress | Absorption | Depersonalization | Amnesia | Dissociation | ||||||||||||||||

| independent variable | Coeff | SEa | Coeff | SEa | Coeff | SEa | Coeff | SEa | Coeff | SEa | ||||||||||

| Perceived stress | - | - | 8.611*** | .842 | 4.019*** | .671 | 3.453*** | .576 | 5.361*** | .601 | ||||||||||

| SHAI | .456*** | .53 | 5.890*** | 1.589 | 4.985*** | 1.267 | 1.768 | 1.087 | 4.214*** | 1.134 | ||||||||||

| MSPSS_others | -.093 | .028 | .089 | .833 | -2.189** | .664 | -1.005 | .570 | -1.096 | .595 | ||||||||||

| MSPSS_family | -.127*** | .020 | -2.675*** | .602 | -1.552** | .480 | -1.343** | .412 | -1.857*** | 0.430 | ||||||||||

| MSPSS_friends | -.044 | .023 | .416 | .666 | .007 | .531 | .295 | .456 | .239 | .475 | ||||||||||

| WCQ_humor | -.076*** | .019 | .228 | .560 | .789 | .446 | .460 | .383 | 0.492 | 0.400 | ||||||||||

| WCQ_pos | -.264*** | .032 | 3.880*** | .964 | 2.307** | .768 | 1.636* | .659 | 2.608*** | .688 | ||||||||||

| WCQ_avoid | .448*** | .036 | 5,092*** | 1.112 | 4.982*** | .886 | 3.168*** | .761 | 4.414*** | .794 | ||||||||||

| WCQ_out | .014 | .032 | .140 | .921 | .237 | .734 | -.650 | .630 | -0,091 | .657 | ||||||||||

| Constant | 2.036*** | .155 | -.968 | 4.81 | -.758 | 3.836 | 3.285 | 3.291 | .520 | 3.434 | ||||||||||

| R2 = .411 F(10,1186) = 82.65*** |

R2 = .244 F(11,1185) = 34.836*** |

R2 = .199 F(11,1185) = 26.818*** |

R2 = .130 F(11,1185) = 16.067*** |

R2 = .244 F(11,1185) = 38.685*** |

||||||||||||||||

| dependent variables | |||||||||||||||||||

| Perceived stress | Absorption | Depersonalization | Amnesia | Dissociation | |||||||||||||||

| independent variable | Coeff | SEa | Coeff | SEa | Coeff | SEa | Coeff | SEa | Coeff | SEa | |||||||||

| Perceived stress | - | - | 7.310*** | 1.483 | 2.651* | 1.346 | 2.697* | 1.178 | 4.219*** | 1.184 | |||||||||

| SHAI | .525*** | .087 | 9.230** | 2.900 | 6.512* | 2.632 | 4.507 | 2.305 | 6.750** | 2.316 | |||||||||

| MSPSS_others | .005 | .020 | .173 | .658 | -.674 | .597 | -.290 | .523 | -.264 | .525 | |||||||||

| MSPSS_family | -.031 | .021 | .616 | .689 | .453 | .626 | .075 | .548 | .381 | .551 | |||||||||

| MSPSS_friends | -.063** | .023 | .147 | .748 | -.706 | .679 | .190 | .595 | -.123 | .598 | |||||||||

| WCQ_wishful | .560*** | .050 | 7.512*** | 1.800 | 4.465** | 1.634 | 1.589 | 1.431 | 4.522** | 1.438 | |||||||||

| WCQ_goaloriented | -.274*** | .054 | -2.248 | 1.779 | -2,496 | 1.615 | -1.708 | 1.414 | -2.151 | 1.421 | |||||||||

| WCQ_seeksupport | .079 | .049 | -3.597* | 1.571 | .506 | 1.426 | 1.684 | 1.249 | -.469 | 1.255 | |||||||||

| WCQ_avoid | -.010 | .046 | 1.398 | 1.466 | 3.191* | 1.331 | 2.176 | 1.293 | 2.893* | 1.299 | |||||||||

| WCQ_thinkover | -.186 | .050 | 4.464** | 1.627 | 2.039 | 1.477 | 2.991* | 1.165 | 2.527* | 1.171 | |||||||||

| Constant | 1.310*** | .219 | -23.218** | 7.325 | -14.271* | 6.649 | -13.786* | 5.822 | -17.091** | 5.850 | |||||||||

| R2 = .456 F(11,471) = 35,910*** |

R2 = .334 F(12,470) = 19.643*** |

R2 = .193 F(12,470) = 9.373*** |

R2 = .137 F(12,470) = 6.217*** |

R2 = .262 F(12,470) = 13.936*** |

|||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).