Introduction

Schrödinger [

1], called entanglement not one but rather the characteristic trait of quantum mechanics. Schrödinger’s statement is prophetic. The departure from classical is the existence of quantum coherence in addition to polarized states. We embrace entanglement as a vital property of quantum mechanics, but reject that it persists in non-local situations.

This paper is the second of three in which quaternion spin is presented. The first paper, [

2], uses Quantum Field Theory to modify the Dirac equation by changing the symmetry of a spin from SU(2) to the quaternion group. This introduces a bivector,

which is the origin of helicity. It shows that spin carries two complementary properties, polarization and coherence.

This paper follows the first in which the ideas are used to study helicity applied to an EPR pair and which is responsible for the observed correlation. It shows the anti-symmetric part of a spin generates the spinning of the axis of linear momentum in free flight. The third paper, [

3] presents a computer simulation which shows that both polarized and coherent states are responsible for the apparent violation of Bell’s Inequalities (BI). In this work, there are no Local Hidden Variables (LHV) and consequently Bell’s theorem is either not applicable or is not violated.

An EPR pair refers to the two particles initially in a singlet state, then separate. Although it is commonly believed, as justified by Bell’s theorem, [

4] that entanglement persists to space-like separations, in this work persistent, non-local entanglement is not used. Rather EPR pairs are separated particles and form a product state. Correlation between EPR pairs is then due only to their history which depends upon their common orientation at the time of separation.

The correlation measured in coincidence EPR experiments, [

5,

7,

8] is considered evidence for non-local connectivity between EPR pairs [

4]. The three papers presented here give an alternate explanation. We show the property of hyper-helicity (or simply the helicity) accounts for the apparent violation of BI, [

9]. In this paper we present the geometric arguments that support the existence of helicity as an element of reality of spin, in addition to the usual measured polarization.

We stress that helicity defined here is different from the usual definition, [

10]. In this work, hyper-helicity is not the projection of the spin vector along the axis of linear momentum. Like polarized spin, it is an element of reality and is an additional source of the correlation that is present in EPR experiments. Hyper-helicity spins the axis whereas particle helicity measures it.

Polarizations,

, are measured directly, coherencies,

, are not. Helicity possesses no handle to couple to a probe field, and indeed helicity is destroyed in anisotropy. Nonetheless we find that coincidence EPR experiments are sensitive to both polarization and helicity which together contribute to the observed correlation without non-local connectivity [

11].

In the following, we examine the process of separation or an EPR pair that conserves linear momentum, angular momentum, handedness, or helicity, and correlation.

The treatment uses state operators, [

12] and projective measure of von Neumann, [

13], to calculate the spin correlation. The formulation of Irreducible Cartesian Tensors [

14] reveals the geometry of the singlet and its structure after separation.

The Singlet State and Separation

Our view of a singlet state is based upon the cancellation of polarization. Looking at the usual definition of the singlet, we express two generic states each for Alice and Bob,

, by the up/down outcomes, and so the singlet state is constructed in the usual way

These states display orthogonalities:

and

. By generic we mean that the orientation of the states is not specified and any direction may emerge as long as it is the same for both Alice and Bob.

From Equation (

1) we notice that the isotropy of the LHS is reflected in the way we construct the RHS from anti-parallel anisotropic states that obey the statistics of fermions, which we use in turn to ensure that the singlet is odd to particle interchange: that description

is too simplistic.

As a singlet separates into an EPR pair, it does so in opposite directions, with opposite polarization and opposite helicities. Separated EPR pairs conserve: linear momentum, angular momentum and helicity. We also find a new law describing the Conservation of Geometric Correlation between entangled and separated spins.

In the following section, these points are formalized. The apparent violation of BI is due entirely to the presence of correlation due to helicity. It has nothing to do with non-locality.

To reflect the experimental configuration where the two filters are co-planar, we set , , where represents the quantum correlation between EPR pairs.

Geometry

In this section it is shown there is no loss of correlation upon separation. The correlation measured in coincidence experiments, and present in the entangled local singlet state, is carried by the two particles being divided between the polarization of the spins and their quantum coherence, i.e. their helicities.

The singlet state density operator is found by taking the outer product of the singlet, Equation (

1) giving a 4x4 density matrix, which is entangled

In the process of separation, in contrast, we usually assume that the two oppositely polarized spins leave in a definite orientation, say

, given by the direct product of two spin state operators. This is expressed by

The Local Singlet

The expectation value for the correlation is defined by the quantum trace over the operators, [

12].

where † is the operator adjoint. The correlation due to polarization of the spins between different filter settings is given by

Remove the filter components

and

to focus on the expectation value only

giving the usual result for the spin correlation from quantum mechanics,

which leads to the apparent violation of Bell’s inequalities (BI).

Here

is the totally symmetric second rank tensor being the identity in 3D Cartesian space. Let us choose the representation of this tensor in a convenient basis to describe the spin,

with orthogonality of

. From Equation (

6), note the contractions between Alice and Bob. The only source of correlation between EPR pairs in this treatment is through these contractions. The two

’s must share the same coordinate frame in order to be correlated. This frame is determined as the EPR pair separated.

The Product State

Using Equation (

3) gives

and this result can only satisfy, and not violate, BI. In Equation (

9) we have set

which gives the two cosines shown.

The Source

As the particles leave the source, the filters and their settings,

, are far away and we do not need the quantum trace,

and the operator describing a spin in free flight is the dyadic,

, see Equation (

6). This can be expressed using Geometric Algebra, [

14] which for three-dimensional real space is

in terms of the three components of the Levi-Civita tensor,

which is the three dimensional totally anti-symmetric Cartesian tensor. The first term gives,

, is seen in Equation (

7), but the second term traces out and the anti-symmetric part makes no contribution to the correlation between the measured polarized states,

, see Equation (

5).

We deduce the formation of a local singlet involves two spins aligning to cancel their magnetic moments. Additionally, helicity spins the common axis of the singlet state, . Both physical quantities are still present in the singlet state, but both cancel out leaving isotropy.

Upon separation, the up/down polarized spins re-appear along with R/L coherent helicity.

Helicity

We define the geometric helicity as a second rank operator by

which is anti-Hermitian and rotates the plane perpendicular to the bivector,

. The sign of the helicity is due to its anti-symmetry. Introduce a permutation (parity) operator to permute the indices

i and

j, which are indistinguishable in isotropy. The operator

is odd to parity indicating helicity spins left or right,

The correlation between the helicity of the two spins in coincidence polarizing experiments is defined and given by

That is,

where the three vectors,

, are coplanar for

. Once again the correlation is determined by the contractions, and the vector

must be the same for both partners.

Conservation of Geometric Correlation

The correlation between two spins in a local singlet is:

The correlation from an EPR pair arises from both the polarization of the spins and their helicity,

Correlation is preserved between the entangled local singlet and the EPR pair which can be expressed in purely geometric terms,

which articulates the Conservation of Geometric Correlation between an isotropic singlet and its EPR pair. There are several equivalent ways to express this, e.g. Equation (

12). This result can also be generalized to

n-tuples, [

16] and correlation is always conserved.

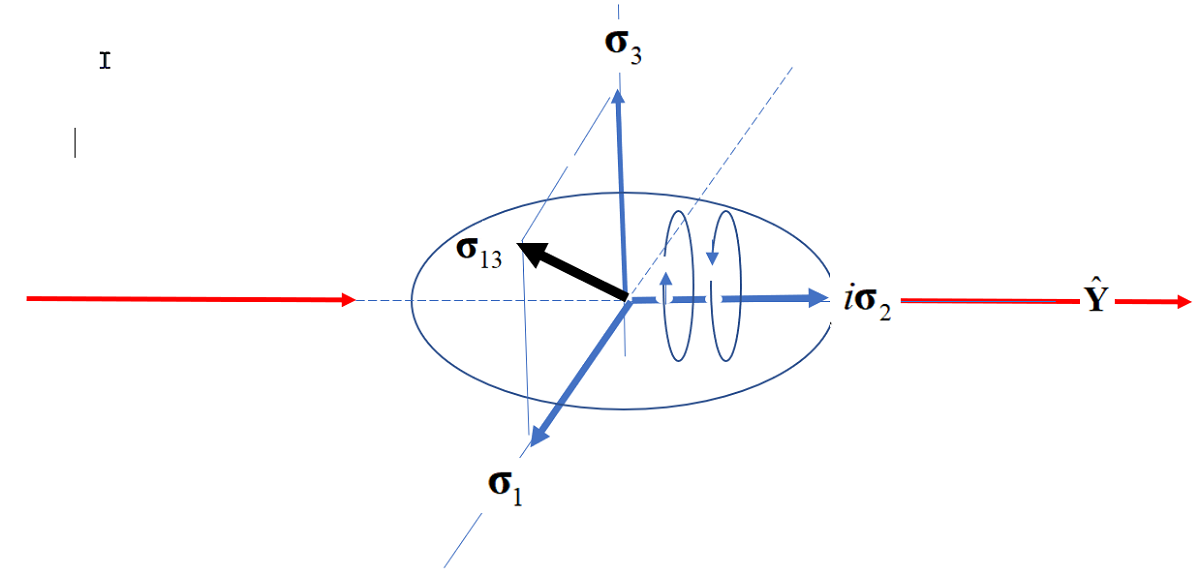

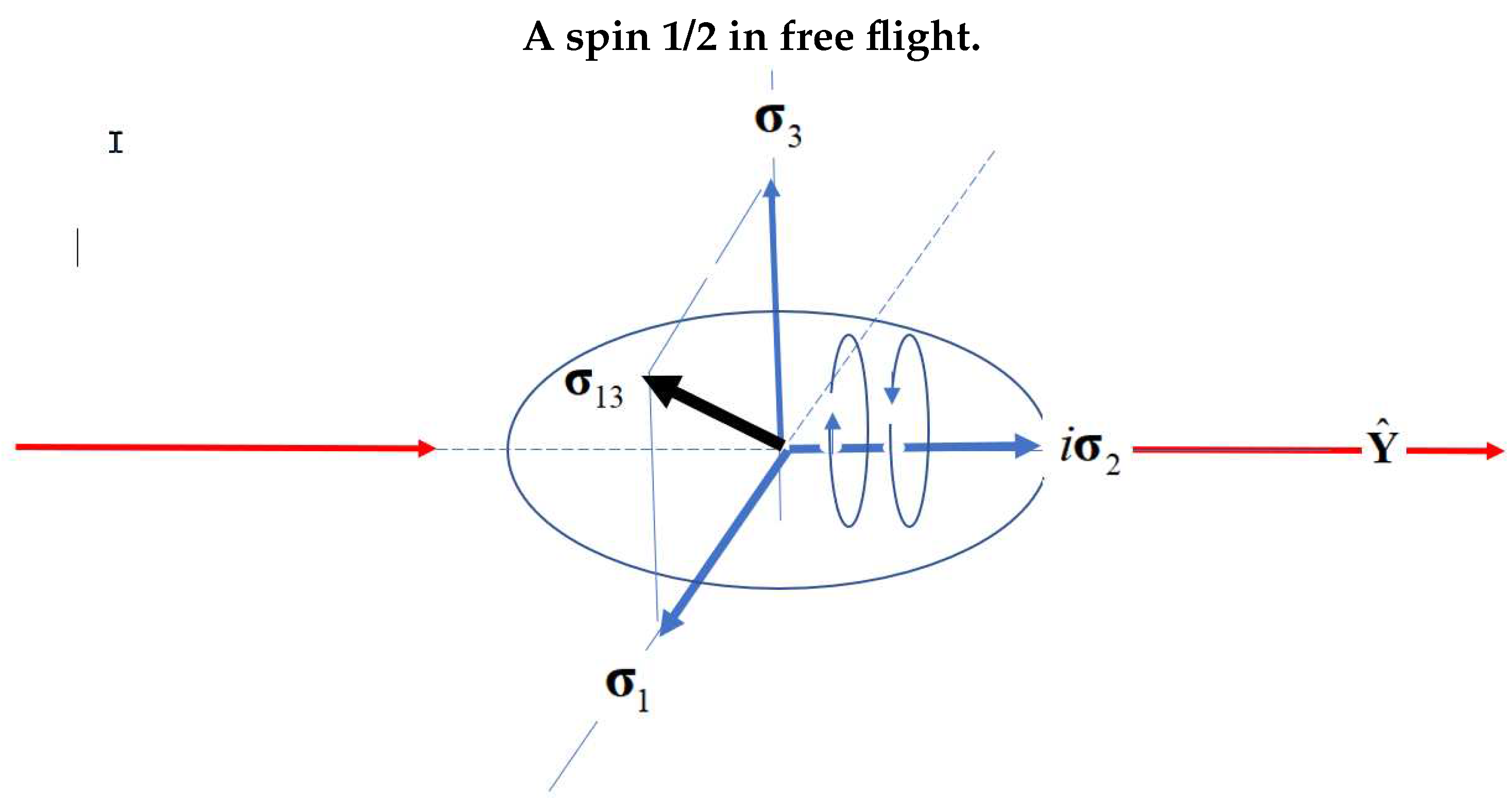

Visualization of a Spin in Free Flight

Dirac spin is described as a point particle of intrinsic angular momentum. It arises from the Dirac equation with spin emerging as a vector operator with components of the Pauli spin vector and belongs to the SU(2) group.

In contrast, the intrinsic angular momentum of Dirac spin becomes extrinsic for quaternion spin which is generated by the helicity. This requires the presence of a bivector, and the only mathematical alternative that includes it [

17], [

18] is obtained by changing the symmetry to the quaternion group [

2]. This leads to a geometric structure of spin identical to that of a photon: the free spin propagates with hyper-helicity in the direction of linear momentum with two orthogonal components of angular momentum perpendicular to that direction. These two spins of

couple to give a resonance spin of magnitude 1 as more fully explained in [

3]. The spinning axis averages the spin polarization of 1 to zero, see the

Figure 1.

The helicity defined here does not exist in Minkowski spacetime. Rather, it exists in coherent hyperspace,

, the 4th dimensional hypersphere that carries the unit quaternions, [

15], hence the name hyper-helicity. This is generated by the helicity operator, Equation (

13), a real property of spin distinct from polarization.

Conclusions

A spin in free flight carries both helicity and polarization but when encountering a probe field, only one angular momentum axis can align, giving the usual Dirac state. A Dirac spin has no degrees of freedom, it is a point particle, whereas quaternion spin has internal degrees of freedom from the helicity and axes of quantization. Helicity, , and angular momentum, are incompatible elements of reality. They epitomize the wave-particle duality of quantum theory.

Accepting helicity requires justification at the level of the Dirac equation, [

19]. This is presented in the first paper, [

2], by changing the spin symmetry to the quaternion group. This extension of the Dirac equation separates the Dirac field into two spaces: one for Hermitian polarization and the other anti-Hermitian coherence. Since a quaternion exists in the

hyperspace, then we conclude that Nature has spatial dimensions that exist beyond our spacetime.

A significant reason that it took us 100 years to discover hyper-helicity lies in being able to observe only the stereographic projection of spin onto our spacetime, that being the observed point particle of Dirac spin, . The helicity is lost in the projection leaving us with only the polarized states of the vector to observe.

A spin state is more fully expressed by

where the helicity is now included as a direct product with states polarized in direction

, and with helicity states of

, see the

Figure 1.

In Stern-Gerlach experiments the helicity is not observable and upon measurement information is lost .

If one wishes to accept that spin always carries values of either , and reject helicity, then non-locality appears to be the only alternative.

It is our view that the only physically reasonable definition of entanglement restricts it to local situations. The geometric consistency with the structure of a photon in the

Figure 1 gives an alluring credibility to our description of spin in free flight. Stretching out entangled “EPR" channels, [

11], to “connect" to a distant partner to account for correlation, rather than two partners knowing their right from left, is something Occam would have no difficulty with.

If the treatment here is accepted, then the violation of BI is not evidence for non-locality, but rather for local realism. We conclude that quantum mechanics is an elegant theory of measurement, but is restricted to our spacetime.

In the third paper, [

3], these ideas are verified with a computer simulation which brings out additional features and properties of quaternion spin.

References

- Schrödinger E., “Discussion of probability relations between separated systems". Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 31 (4): 555–563 (1935). [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. Extrinsic Quaternion Spin. Preprints 2023, 2023020055. [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. Non-local EPR correlations using Quaternion spin. Preprints 2023, 2023010570. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. S. (2004). p. 139 or 147, Speakable and unspeakable in quantum mechanics: Collected papers on quantum philosophy. Cambridge university press.

- Clauser, J. F., Horne, M. A., Shimony, A., & Holt, R. A. (1969). Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Physical review letters, 23(15), 880. [CrossRef]

- Aspect, Alain, Jean Dalibard, and Gérard Roger. “Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers.” Physical review letters 49.25 (1982): 1804. [CrossRef]

- Aspect, Alain (15 October 1976). “Proposed experiment to test the non separability of quantum mechanics”. Physical Review D. 14 (8): 1944–1951. [CrossRef]

- Weihs, G., Jennewein, T., Simon, C., Weinfurter, H., Zeilinger, A. (1998). Violation of Bell’s inequality under strict Einstein locality conditions. Physical Review Letters, 81(23), 5039. [CrossRef]

- Bell, John S. “On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox." Physics Physique Fizika 1.3 (1964): 195.

- Schwartz, M. D. (2014). Quantum field theory and the standard model. Cambridge University Press.

- Bennett, C. H., Brassard, G., Crépeau, C., Jozsa, R., Peres, A., Wootters, W. K. (1993). Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. Physical review letters, 70(13), 1895. [CrossRef]

- Fano, Ugo. “Description of states in quantum mechanics by density matrix and operator techniques." Reviews of modern physics 29.1 (1957): 74. [CrossRef]

- Von Neumann, John. Mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics. Princeton university press, 1955.

- Snider, Robert F., Irreducible Cartesian Tensors, Vol.43, De Gruyter Studies in Mathematical Physics, de Gruyter, Berlin, 2018.

- Doran, C., Lasenby, J., (2003). Geometric algebra for physicists. Cambridge University Press.

- Sanctuary, B. C. (1976). Multipole operators for an arbitrary number of spins. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 64(11), 4352-4361. [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. C. “The two dimensional spin and its resonance fringe." arXiv preprint arXiv:0707.1763 (2007).

- Sanctuary, B. C. “Structure of a spin 1/2." arXiv preprint arXiv:0908.3219 (2009)..

- Peskin, M. E., Schroeder, D. V. (1995). An Introduction To Quantum Field Theory (Frontiers in Physics), Boulder, CO.

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1928). The quantum theory of the electron. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character, 117(778), 610-624. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).