1. Introduction

Dementia is the estimated prevalence and its growth rate is increasing, thus leading to increased medical expenditures to hundreds of billions of USD. Dementia-related health problems have become a prioritized topic at the national and community levels [

1]. Dementia is a neurodegenerative process that affects memory, social behavior, the activities of daily living, and sleep; reduced nocturnal parasympathetic activity may represent the early predictive factors for progression to dementia [

2]. Dementia is often characterized by autonomic dysfunction, particularly with reduced parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) activity. Moreover, greater sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity at night is related to poorer cognition and sleep quality [

3,

4]. Cognitive disorders in individuals with dementia lead to increased SNS activity; decreased PSNS activity appears to be associated with worse performance in cognitive domains, which may be related to impaired autonomic regulation and self-regulatory neural circuits [

2,

5].

The principal regulators of the sleep-wake cycle and the control of autonomic activity are located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), predominantly including the neuroendocrine and hypothalamic pathways that balance the mechanisms of nerve conduction [

6,

7]. While the SNS is similar to the gas pedal of an automobile, energizing the body to cope with external challenges, the PSNS acts like the braking system, decelerating the metabolic rate to facilitate the body to enter into a quality sleep mode. The PSNS maintains a default state, thereby contributing to baseline repair and nutrient storage functions. By contrast, the SNS includes neurological and humoral elements that facilitate real-time reactions to dyshomeostasis. The activity of the ANS, which consists of the SNS and PSNS, reflects normalized low-frequency (LF%) and high-frequency (HF) power in heart rate variability (HRV) data. The LF/HF ratio quantifies the sympathovagal balance to reflect the modulations of SNS activity [

8,

9].

BML is a non-invasive, simple, easy-to-operate, and cost-effective therapy with limited side effects for individuals with age-related sleep disturbances [

10]. These effects of light are mediated by intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs). IpRGCs involve a pacemaker-independent input to the SCN, which is the master circadian clock in the human body localized in the hypothalamus over the optic chiasm [

11]. The SCN is vulnerable to aging characterized by a decreased sensitivity of the eyes to light and the diminished transmission of light by the lenses, caused by a reduced pupil diameter and yellowing of the lenses. Consequently, these factors hinder the entry of light, which is necessary for rhythm synchronization, thus explaining the worsening of circadian disruption in older people with an insufficient exposure to daylight during the day [

12]. Light therapy can reduce nighttime awakenings, enhance sleep quality [

13], and advance the circadian rhythm phase, thus reducing the phase delay as well as nighttime awakening; eventually, it reduces sleep disturbances [

14]. An exposure to BML induces advances in sleep onset, delays sleep offset [

15], and improves cognitive function [

11,

16] in older adults with dementia. Hence, sleep quality can be used as an index of PSNS activation and SNS deactivation at night [

4,

8,

9,

17].

The ANS is strongly related to the central autonomic network. The bidirectional communication between these systems is the crossover of the connection between the brain and body, where the brainstem structures supposedly generate output to the heart [

18]. HRV is the complex beat-to-beat variation in the heart rate produced by the interactions of sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal) neural activity at the sinus node [

19]. HRV is a non-invasive valid measure for detecting awakenings during sleep and has been applied to understand the effects of insomnia, sleep disorders, cardiorespiratory function, immune function, cognitive function, and neurodegenerative diseases in individuals with dementia [

4,

5,

7,

20]. The relationships among HRV parameters provide additional insights into the mechanisms underlying autonomic homeostasis [

2,

4]. According to ANS studies conducted at night, washout light exposure reduces the effect and cognitive function. However, the impact of BML exposure on the ANS at night is unclear, particularly in older adults with dementia. There are insufficient data on the effects of BML exposure on the brain.

We hypothesized that an exposure to BML would exert beneficial effects on autonomic regulation at night, with an increase in PSNS activity and a decrease in SNS activity, and that a week-long washout BML exposure would reduce the effects. We aimed to perform longitudinal experiments using noninvasive recording methods. Furthermore, we intended to explore the relationship between BML exposure and cognitive function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

We performed a non-randomized controlled pilot study with repeated measures. The research protocol (YM107120F) was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board. The participants and family caregivers signed the written informed consent form prior to enrollment.

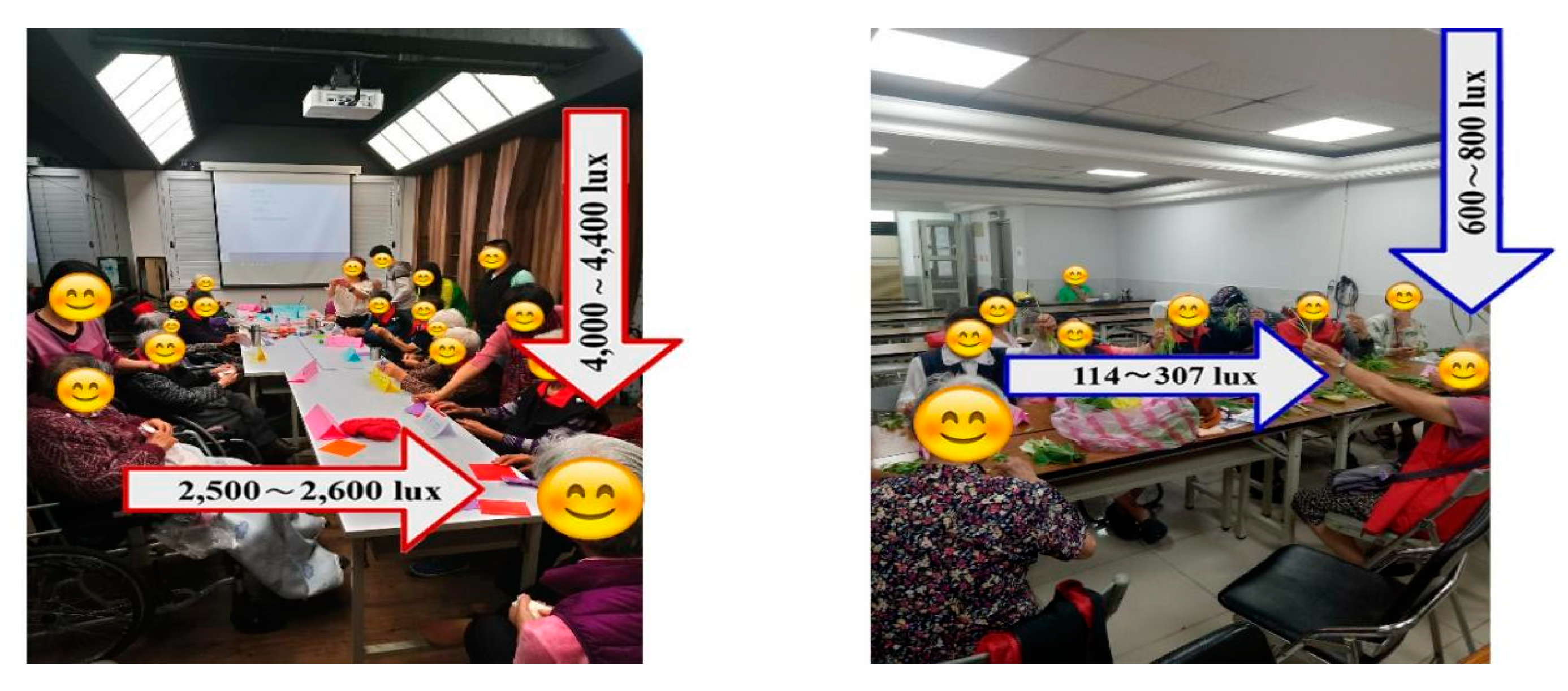

BML (2500 lx) and general light were used for the treatment group and control group, respectively, in a parallel intervention study design. The study protocol had a duration of 8 weeks. We assessed the outcome measures at the end of the baseline and following 5 weeks of intervention. Following 8 weeks of intervention, we performed a 1-week washout period. The outcome measures were assessed at the end of the week, thus generating data collected at three time points as follows: baseline, week 5 (Posttest 1, ongoing light intervention), and week 9 (posttest 2, following the 1-week washout period).

2.2. Participants

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) participants diagnosed with any type of dementia or cognitive disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition [

21]; 2) aged ≥60 years; 3) consented to participate in the study (both participants and their caregivers); and 4) willing to be monitored with an HRV instrument at the end of the study. The exclusion criteria were as 1) conditions that caused adverse reactions to light, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, epilepsy, retinal detachment, or macular degeneration, or 2) had a pacemaker and a medical history of arrhythmia

[22], according to the reports of the caregivers and nursing home staff.

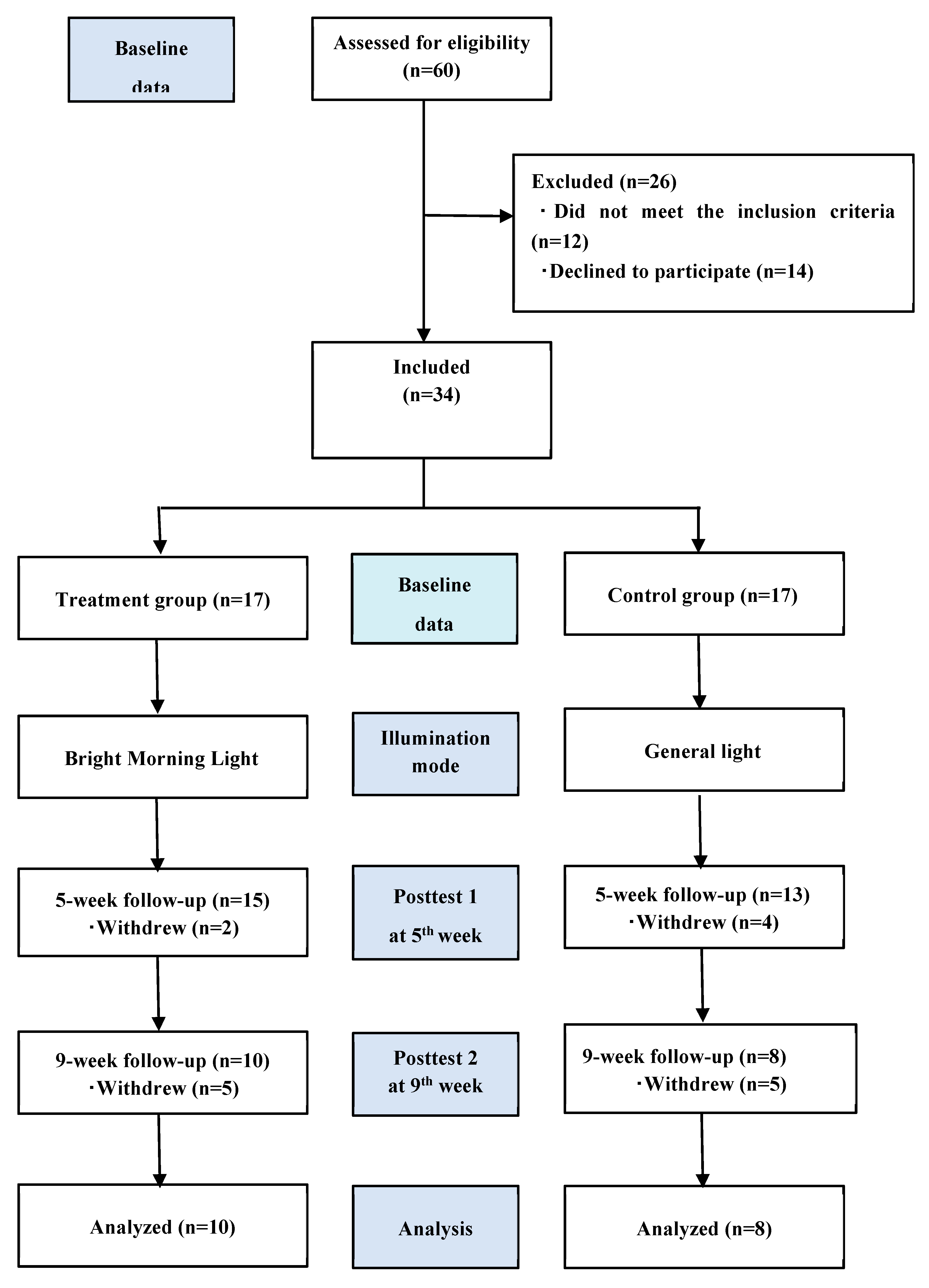

Of the 60 eligible participants, 12 did not meet the inclusion criteria and 14 dropped out of the study. Accordingly, we enrolled 34 patients who were consecutively allocated to the treatment (n=17) and control (n=17) groups. Eventually, only 18 patients completed the study (

Figure 1).

2.3. Intervention group

The treatment group received bright light therapy with horizontal illuminations of 2500 lx delivered by a panel light (

Figure 2) in a designated room from 9:00 AM to 10:00 AM over 8 weeks (5 days/week). They received bright light therapy for 40 h in a group setting. The intervention and screening procedures have been reported in a prior publication [

15,

16].

2.4. Instruments and outcome measures

We determined the primary outcome measures, including the mean values of the trial variables, HF power, LF power %, and LF/HF ratio, from HRV data. We used the PSNS activity indicator and HF component determined from HRV data. The SNS activity indicator and LF% component were determined from HRV data. The sympathovagal balance indicator and LF/HF ratio were derived from HRV measures. Data were analyzed at the baseline and at Posttest 1 and Posttest 2 (following a 1-week washout period) from April 2019 to December 2019. The data collectors were blinded to the group allocation. We determined the corresponding SNS outcomes using LF% power and the sympathovagal balance indicator with the LF/HF ratio; PSNS data were obtained using HF power. Cognitive function was the secondary outcome measure, which was assessed by the researchers who directly collected the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores. They explored the relationships between cognitive function and the HF power, LF% power, and LF/HF ratio.

2.4.1. Validity and reliability of HRV data

We assessed one component each in the LF range (i.e., 0/04–0.15 Hz) and HF range (i.e., 0.15–0.40 Hz). The LF power was normalized to HF power (e.g., [HF/(HF+LF)×100]) to remove the effects of very-low-frequency (VLF) bands and to detect the effects of SNS activity on HRV. We used the LF/HF ratio to quantify the sympathovagal balance and reflect the modulations of SNS activity. The LF/HF ratio is significantly negatively correlated with the delta power measured by electroencephalography (0.5–4.0 Hz) during quiet sleep, whereas cardiac sympathetic regulation is negatively correlated with the depth of sleep [

23]. Detailed procedures for the analysis of HRV have been reported in our previous study [

24]. Pacemaker use and arrhythmia were associated with increased heart rate fragmentation, which reduced the HRV accuracy [

25].

The HRV device (WG-103A, Taipei, Taiwan) was placed over the sinus node to enable continuous long-term recording during hours 1-7 of lying in bed overnight and for ≥1 day at the baseline, Posttest 1, and Posttest 2 using the KY laboratory software package (

http://xenon2.ym.edu.tw/hrv/). We adjusted the HRV parameters for interference factors, system settings, and statistical settings, besides excluding the extreme values. The real-time signal was transmitted to a smartphone using Xenon-Bluetooth Low Energy. Specifically, HRV was recorded as a precordial electrocardiograph. HRV exhibits a higher sensitivity and lower specificity than polysomnography [

26,

27]. HRV measurements were continuously performed between 7 PM (19:00) and 7 AM (07:00).

2.5. Statistical analyses

We used repeated measurement generalized linear models (GLMs) to analyze the effects of BML exposure on the HRV parameters at night [

28,

29]. The GLMs included results collected over seven consecutive hours. We compared the efficacy of bright light therapy to that of general light therapy and the time point (baseline, Posttest 1, and Posttest 2), whereas "interaction" (group × time point) was used to calculate the statistical significance. The analyses were performed using SPSS 24 software, and

P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant (

P<.05).

Thus, a significant interaction effect indicated a significant between-group (treatment vs. control groups) difference in the changes over hours 1-7 of lying in bed overnight (Posttest 1 and baseline vs. Posttest 2 and baseline). Eventually, we used the MMSE to determine the cognitive severity of dementia. This helped us explore the relationships between cognitive function and HRV parameters. Scores ≥21, ranging from 11 to 20, and from 0 to 10 indicated the presence of mild, moderate, and severe dementia, respectively [

16,

30].

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

Figure 1 presents the study flowchart. Thirty-four participants completed the baseline assessment. The retention rates were 58.8% and 47.1% in the treatment and control groups, respectively.

Table 1 summarizes the between-group comparisons of demographic characteristics using chi-squared tests. There were no differences in the baseline characteristics between the participants across the groups. Conversely, we observed a significant between-group difference in the sex ratio, with men comprising 5.9% and 35.3% of the patients in the treatment and control groups, respectively (

P<.05). Furthermore, Mann–Whitney U tests did not detect any significant between-group differences in the demographic factors, HF power, LF%, or LF/HF ratio at baseline. The patients’ ages were 83.9 (SD, 7.2) and 79.8 (SD, 7.1) years in the treatment and control groups, respectively.

3.2. Primary outcomes

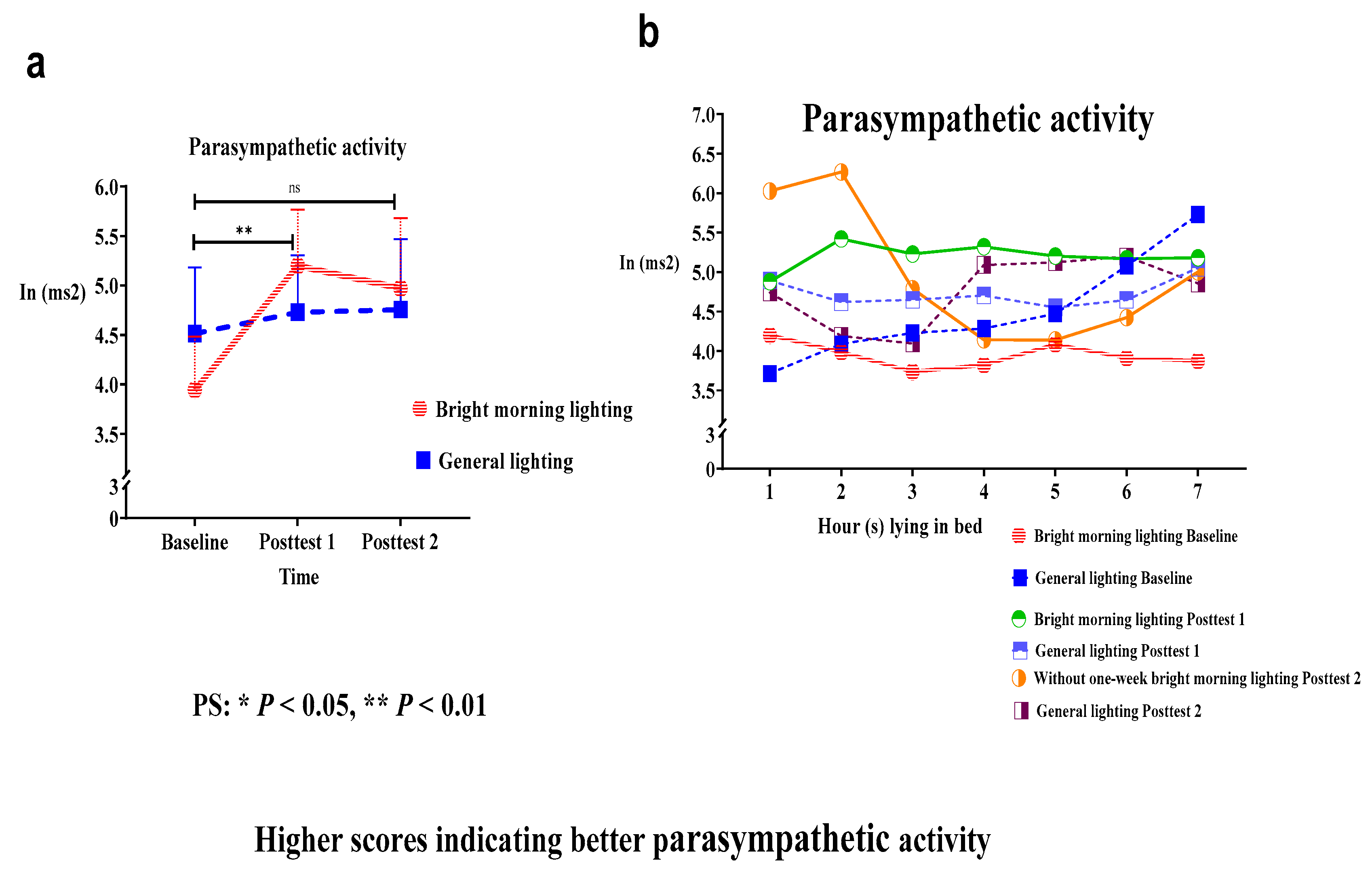

3.2.1. Effects of BML on PSNS activity

The present study used the PSNS activity indicator (i.e., the HF component determined from HRV data) to assess the effects of BML exposure. We analyzed the main effect of the group × time interaction on HF power; the HF power had significantly improved. Specifically, we identified significant differences in the HF power in the treatment group while lying in bed from hours 1 to 7 at baseline, compared with Posttest 1 (Roy's largest root=2.44;

P<.01) (

Figure 3a and

Table 2). The treatment group demonstrated an early decline in PSNS activity in early morning at Posttest 2 following a 1-week washout period (

Figure 3b).

Both treatment and control groups demonstrated a peak in HF power while lying in bed at hour 2 at the Posttest 1 and Posttest 2 time points. Compared with the treatment group, the control group displayed a greater reduction in the HF power at Posttest 1 and Posttest 2 relative to baseline (

Figure 3b). Therefore, the control group exhibited reduced PSNS activity than the treatment group, thereby resulting in unstable and irregular circadian rhythms.

3.2.2. Effects of BML on SNS activity

The present study used the SNS activity indicator (i.e., the LF% component of HRV) to assess the effects of BML exposure. We observed a significant main effect of the treatment on the LF% power (Roy's largest root=0.53;

P>.05). The treatment group displayed a decrease in the LF% power, compared with the control group. The LF% values at Posttest 1 were lower than those at baseline; however, the difference was statistically insignificant (

Figure 4a and

Table 2). Specifically, the treatment group demonstrated a marked decrease in the LF% power while lying in bed from hours 2 to 3, thus resulting in a U-shaped curve of the relationship between the LF% power and time at Posttest 1 (

Figure 4b). Following a 1-week washout period, the treatment group displayed elevated SNS activity at Posttest 2, with a mean increase of 23% (calculation method: (posttest–pretest)/pretest)) (

Figure 4b).

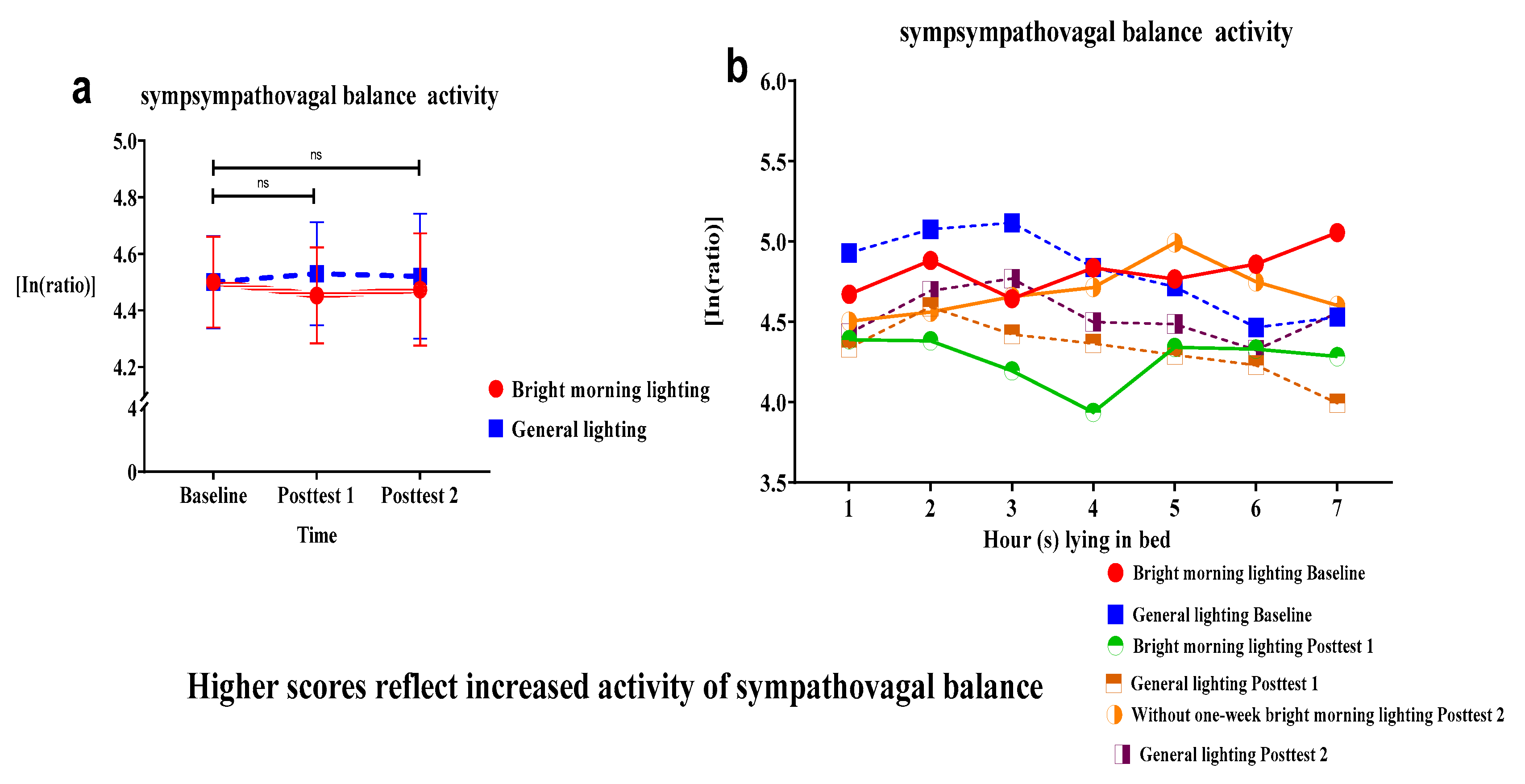

3.2.3. Effects of BML on sympathovagal balance

We used the sympathovagal balance indicator (i.e., the LF/HF ratio derived from HRV measures) to assess the effects of BML exposure. We analyzed the effect of the group × time interaction on the LF/HF ratio. We observed an insignificant decrease in the LF/HF ratio of the treatment group (Roy's largest root=1.09 P>.05). The treatment group displayed no change in the sympathovagal balance at Posttest 2.

It demonstrated a larger mean decrease than the control group at subsequent time points relative to the baseline (

Figure 5a and

Table 2). Specifically, individuals in the treatment group demonstrated a marked decrease in the LF/HF ratio while lying in bed from hours 3 to 4, thus generating a U-shaped curve of the relationship between the LF/HF ratio and time at Posttest 1 (

Figure 5b).

3.3. Secondary outcomes

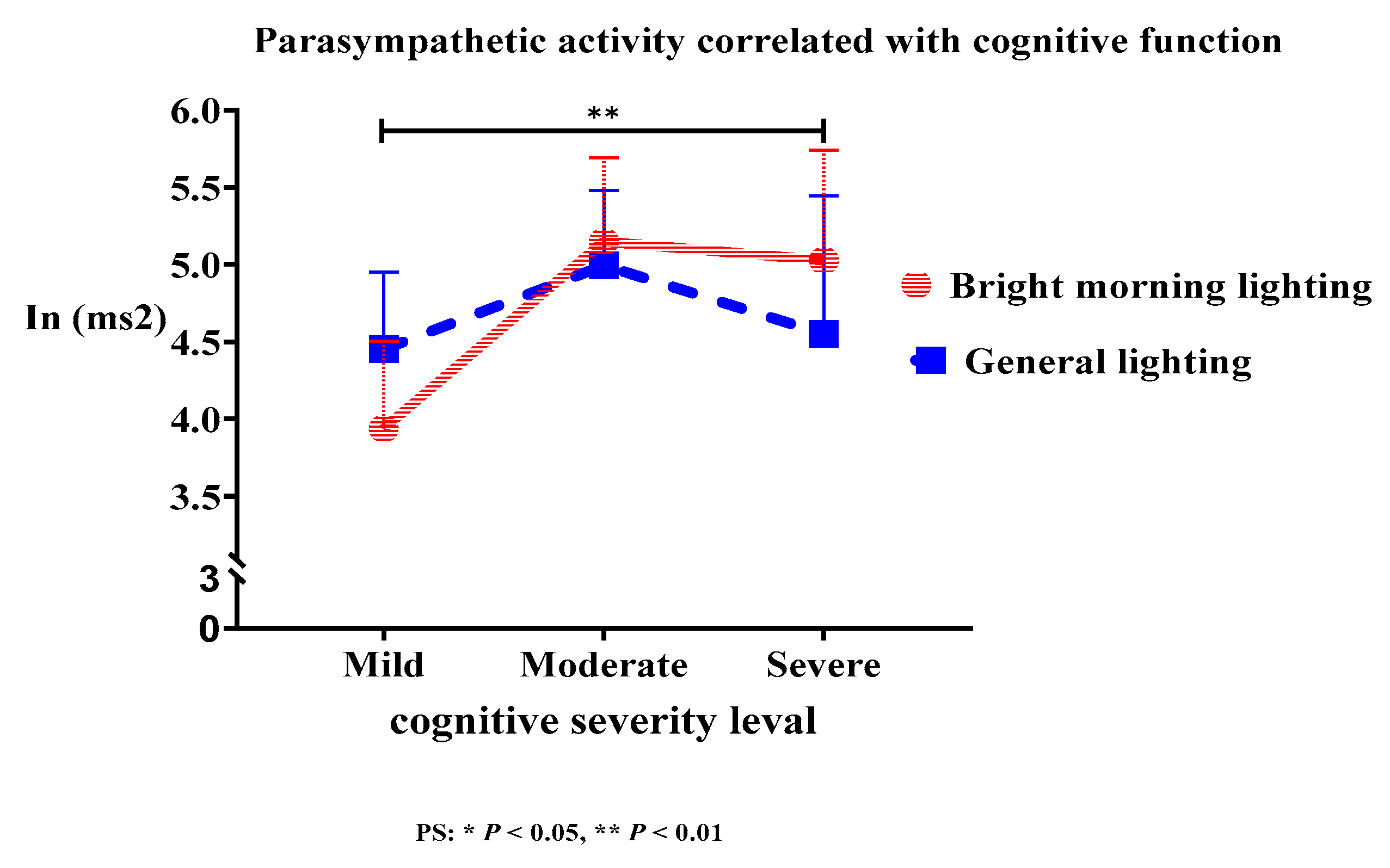

3.3.1. Effect of HF, LF%, and LF/HF on cognitive function

The treatment group demonstrated a significant correlation between cognitive function and HF power (Roy's largest root=3.92;

P<.01). BML exposure enhanced PSNS activity at night, which is more effective for moderate dementia than that for severe and mild dementia (

Figure 6). However, the differences in LF% power and LF/HF ratio did not reach statistical significance. Moreover, the activation of the PSNS in older adults with dementia was associated with cognitive function at night. This can be attributed to a significant correlation between PSNS activation and cognitive function (

Table 2).

4. Discussion

This pilot study demonstrated that BML exposure significantly enhanced PSNS activity and reduced SNS activity, thereby enabling the establishment of stable and regular circadian rhythms. By contrast, the rebound intervention markedly boosted SNS activity and decreased PSNS activity in the early morning 1 week following the light washout intervention.

BML exposure markedly enhanced PSNS activity, with a peak at Posttest 1. Moreover, nighttime PSNS activity was associated with cognitive function. Furthermore, the BML intervention increased the peak PSNS activity while the participants were lying in bed during hours 1 to 2. By contrast, the decrease in SNS activity while the participants were lying in bed during hours 2 to 3 resulted in a U-shaped curve of the relationship between SNS activity and time. The reduction in sympathovagal balance while the participants were lying in bed during hours 3 to 4 resulted in a U-shaped curve of the relationship between sympathovagal balance and time.

BML exposure markedly enhanced PSNS activity and reduced SNS activity at night, while markedly boosting SNS activity at night 1 week following the light washout period. Therefore, we recommend BML for driving sleep propensity. PSNS activity was correlated with cognitive function; however, the present study involved fewer participants. This necessitates additional research with a larger cohort to confirm our findings.

4.1. BML exposure enabled stable circadian rhythm and the postponement of dementia disease progression

A previous study reported that morning light cures and night light kills [

31]. Thus, an exposure to BML and darkness following dusk are beneficial for patients with sleep disturbances. The resulting synchronization of the circadian rhythm represents an effective intervention for individuals with neurodegenerative diseases [

11].

The effects of light exposure are mediated by ipRGC pathways involving a pacemaker-independent input to the SCN. The SCN is the biological basis for circadian rhythm (rest-activity, sleep-wake cycles, master circadian clock, autonomic activities, body temperature, and melatonin excretion rhythm). However, it becomes vulnerable in the aging process, particularly in people with dementia [

6,

7,

32], while longer sleep deprivation affects the circadian clock, which is less susceptible to light [

33].

BML increases the amplitude of SCN signals [

10,

13,

34], which indicates that a strong central clock induces periods of deep sleep and is efficacious against neurodegenerative diseases [

11,

33]. The circadian rhythm plays a fundamental role in regulating biological functions, including waking time and hormone secretion. Furthermore, clock genes play important roles in circadian regulation. However, a disruption in the expression of these genes underlies the pathological mechanisms of metabolic diseases, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases [

11,

14,

15,

35]). BML activates molecules and cells in the body, such as immune cells, inflammatory mediators, and bone marrow-derived stem cells. These cells help preserve neuronal functions by releasing nerve growth factors or brain-derived neurotrophic factors. These neurotrophic factors alter neurotransmission and disrupt the levels of neurotrophic factors, causing the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia [

11].

PSNS activity peaked while the participants at baseline were lying in bed from 3 to 4 AM, whereas maximal PSNS activity was observed in healthy participants at 2 AM [

36]. BML exposure advanced PSNS activity peaked, which potentially reduced the phase delay. PSNS activity peaked while the participants were lying in bed from 1 to 2 AM, whereas maximal PSNS activity was observed in healthy participants at 2 AM [

36]. The body reaches its lowest temperature between 4 AM and 5 AM; BML exposure following this time will adjust the biological clock to advance sleep onset [

29]. BML therapy is the forefront treatment to induce the resynchronization of circadian rhythms, reduce sleep disturbances, and mitigate the development of neurodegenerative diseases.

Our findings were consistent with previously reported outcomes. BML exposure resulted in improvements, such as the induction of stable and regular circadian rhythms, in the treatment group, compared with the control group.

4.2. BML exposure enhanced PSNS activity the maximum at night

The effects of BML may indicate THE possible integrations of recent work regarding the alleviation of the allostatic load, polyvagal theory, neurovisceral integration model, and emerging evidence on the roles of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and decreased glutamate [

37]. GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter that suppresses the arousal pathways from the brainstem to higher brain centers and initiates the release of relaxation-related neurotransmitters. (e.g., blocking glutamate release, adenosine release inhibitors). GABA is a key regulator of the vagus nerve and is involved in the PSNS. PSNS is largely mediated by the vagus nerve and can “turn off” in response to stressors, which can increase cerebral hyperperfusion [

37,

38]. For example, decreases in the heart rate and blood pressure at night may be positively correlated with PSNS activity [

39].

BML leads to promising outcomes and exerts immediate positive effects on the mood, energy level, and blood oxygen saturation, besides decreasing the mean heart rate in older adults with dementia. Biological responses are physiological indicators of a relaxation response [

29]. BML exposure immediately triggers PSNS activity even at night.

Kong et al. [

2] explored HRV during sleep in older people at a risk of dementia. Participants with amnestic mild cognitive impairment displayed impaired parasympathetic regulation, particularly during non-rapid eye movement sleep. Mental stress induces the activation of the amygdala via the central autonomic system. Efferent projections increase the activation of the SNS and lead to a proinflammatory state that initiates and promotes atherosclerosis, in which cerebral hypoperfusion affects autonomic, mood, and cognitive regulatory cerebral sites [

40]. Furthermore, SNS activity may represent the efferent arm of inflammatory responses, immune responses, and cardiovascular risk [

7]. The vagus nerve acts as a “brake” for the SNS when the PSNS deficit leads to an unrestrained SNS [

39], which leads to the washout BML intervention, such as reducing the vagus nerve actions and triggering boosts in the SNS.

BML exposure enhanced PSNS activity at night, whereas washout BML intervention boosted SNS activity. This feature is the key to postponing the deterioration associated with dementia and warrants further research.

4.3. BML therapy is more effective for severe dementia-enhanced PSNS activity

BML-enhanced nighttime PSNS activity was correlated with cognitive function, and the severity of dementia influenced the elevation of HF at night. In other words, BML therapy is more effective for moderate dementia than that for severe and mild dementia.

Our findings were consistent with previously reported systematic outcomes, in which increased SNS activity and decreased PSNS activity appeared to be associated with worse performance in cognitive domains. PSNS activity is associated with the optimal functioning of the prefrontal-subcortical inhibitory circuits that sustain quick and flexible responses to environmental demands [

41]. It has been associated with greater cortical thickness and a larger amygdala volume in prefrontal regions as well as better performance in attention and executive functioning tests [

39,

42]. By contrast, hyperarousal states have been associated with reduced activation of the brain regions that underlie cognitive control in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex [

18]. Enhancing PSNS activation at night can be used as an index of the sleep quality [

4,

8,

9,

17].

Memory consolidation is primarily attributed to rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. The ability to form and retain non-emotional fact-based memories is associated with the presence and integrity of slow-wave sleep (SWS) [

43,

44]. Disrupted sleep and decreased SWS impair frontal lobe restoration, whereas sleep quality treatments that facilitate amyloid beta clearance and SWS for memory processing specifically focus on memory encoding and memory consolidation [

43,

44,

45]. Cognitive function was correlated with PSNS activity, consistent with previous findings [

2,

5]. Bright light exposure improves attentiveness and cognitive function [

10,

14,

16]. Sleep is crucial in memory consolidation [

43,

46]. In this pilot study, BML exposure improved cognitive function, which may be mediated by the enhancement of the PSNS at night, markedly in deep sleep cycles.

Nighttime PSNS activity is the key predictive factor for sleep-dependent cognitive function because it mitigates a deterioration in cognitive function. Thus, reductions in nighttime PSNS activity may be an early marker of cognitive decline in older individuals with dementia.

4.4. Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the pilot design was reflected in the convenience sampling design, which affected generalizability beyond the present population. Second, the sample size was relatively small, thereby reducing the statistical power and increasing the margin of error, which may have potentially affected the results. Third, the majority of participants were women; therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to men. Fourth, we did not control for the factors affecting HRV, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or dementia type. Fifth, we could not control other aspects, such as the timing of metabolic disease medication use, monitor sleep-wake changes, or control for the age.

5. Conclusions

BML exposure enhanced PSNS activity and was correlated with cognitive function; the activity of the PSNS may have mediated this relationship, which was enhanced at night. Furthermore, the light washout intervention markedly boosted SNS activity at night. This intervention is a non-invasive, simple, and easy-to-operate therapy for older individuals with dementia. It should be continuously applied to maintain the effectiveness.

Author Contributions

All authors conceived and contributed to the design of the experiments and the writing of the manuscript and approved it in its final form. These authors contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, ROC (grant to Yiing Mei Liou, 108-2314-B-010-056-MY2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research protocol (YM107120F) was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University (Taiwan), and the study was developed following the ethical standards embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Ya-Hui Shih for her assistance with data collection. The authors would like to particularly thank the older adults and their caregivers who participated in this study. The authors gratefully acknowledge Tun-Hao Chen from the National Tsinghua University for the fruitful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 02 September 2021).

- Kong, S.D.X.; Hoyos, C.M.; Phillips, C.L.; McKinnon, A.C.; Lin, P.; Duffy, S.L.; Mowszowski, L.; LaMonica, H.M.; Grunstein, R.R.; Naismith, S.L.; et al. Altered Heart Rate Variability during Sleep in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Sleep. 2021, 44, zsaa232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulafia, C.; Duarte-Abritta, B.; Villarreal, M.F.; Ladrón-de-Guevara, M.S.; García, C.; Sequeyra, G.; Sevlever, G.; Fiorentini, L.; Bär, K.J.; Gustafson, D.R.; et al. Relationship between Cognitive and Sleep-Wake Variables in Asymptomatic Offspring of Patients with Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, V.P.; Ramalho Oliveira, B.R.; Tavares Mello, R.G.; Moraes, H.; Deslandes, A.C.; Laks, J. Heart Rate Variability Indexes in Dementia: A Systematic Review with a Quantitative Analysis. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2018, 15, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, G.; Morelli, M.; Grässler, B.; Casagrande, M. Decision Making and Heart Rate Variability: A Systematic Review. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2022, 36, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.M.; Ke, Y.D.; Vucic, S.; Ittner, L.M.; Seeley, W.; Hodges, J.R.; Piguet, O.; Halliday, G.; Kiernan, M.C. Physiological Changes in Neurodegeneration - Mechanistic Insights and Clinical Utility. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccoli, G.; Amici, R. Sleep and Autonomic Nervous System. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2020, 15, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sforza, E.; Pichot, V.; Cervena, K.; Barthélémy, J.C.; Roche, F. Cardiac Variability and Heart-Rate Increment as a Marker of Sleep Fragmentation in Patients with a Sleep Disorder: A Preliminary Study. Sleep. 2007, 30, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, P.K.; Pu, Y. Heart Rate Variability, Sleep and Sleep Disorders. Sleep Med. Rev. 2012, 16, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubiño, J.A.; Gamundí, A.; Akaarir, M.; Canellas, F.; Rial, R.; Nicolau, M.C. Bright Light Therapy and Circadian Cycles in Institutionalized Elders. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Gong, S.Y.; Xia, S.T.; Wang, Y.L.; Peng, H.; Shen, Y.; Liu, C.F. Light Therapy: A New Option for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 2020, 134, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, R.W.; McClung, C.A. Rhythms of Life: Circadian Disruption and Brain Disorders across the Lifespan. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.S.I.; Cheng, L.J.; Chan, E.Y.; Lau, Y.; Lau, S.T. Light Therapy for Sleep Disturbances in Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis and Meta-regression. Sleep Med. 2022, 90, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missotten, P.; Farag, L.; Delye, S.; Muller, A.; Grotz, C.; Adam, S. Role of “Light Therapy” among Older Adults with Dementia: An Overview and Future Perspectives. Geriatr. Psychol. Neuropsychiatr. Vieil. 2019, 17, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.R.; Liou, Y.M.; Jou, J.H. Ambient Bright Lighting in the Morning Improves Sleep Disturbances of Older Adults with Dementia. Sleep Med. 2022, 89, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.R.; Liou, Y.M.; Jou, J.H. Pilot Study of the Effects of Bright Ambient Therapy on Dementia Symptoms and Cognitive Function. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 782160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Goldstein, M.R.; Vazquez, M.; Williams, J.P.; Mullington, J.M. Effects of Sleep and Sleep Deficiency on Autonomic Function in Humans. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2021, 18, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thome, J.; Densmore, M.; Terpou, B.A.; Théberge, J.; McKinnon, M.C.; Lanius, R.A. Contrasting Associations between Heart Rate Variability and Brainstem-Limbic Connectivity in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Its Dissociative Subtype: A Pilot Study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 862192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.C.; Kao, L.C.; Tzeng, N.S.; Kuo, T.B.; Huang, S.Y.; Chang, C.C.; Chang, H.A. Heart Rate Variability in Major Depressive Disorder and after Antidepressant Treatment with Agomelatine and Paroxetine: Findings from the Taiwan Study of Depression and Anxiety (TAISDA). Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2016, 64, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, I. Defining Alzheimer as a Common Age-Related Neurodegenerative Process Not Inevitably Leading to Dementia. Prog. Neurobiol. 2012, 97, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeraki, L.; Michopoulos, I. [Hoarding Disorder in DSM-5: Clinical Description and Cognitive Approach]. Psychiatriki. 2017, 28, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.V.; Heffner, K.; Gevirtz, R.; Zhang, Z.; Tadin, D.; Porsteinsson, A. Targeting Autonomic Flexibility to Enhance Cognitive Training Outcomes in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials. 2021, 22, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, T.B.; Yang, C.C. Scatterplot Analysis of EEG Slow-Wave Magnitude and Heart Rate Variability: An Integrative Exploration of Cerebral Cortical and Autonomic Functions. Sleep. 2004, 27, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, T.B.; Lin, T.; Yang, C.C.; Li, C.L.; Chen, C.F.; Chou, P. Effect of Aging on Gender Differences in Neural Control of Heart Rate. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 277, H2233–H2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.E.V.; Moreira, H.T.; de Oliveira, M.M.; Cintra, L.S.S.; Salgado, H.C.; Fazan, R. Jr.; Tinós, R.; Rassi, A.; Schmidt, A.; Marin-Neto, J.A. Heart Rate Variability as a Biomarker in Patients with Chronic Chagas Cardiomyopathy with or without Concomitant Digestive Involvement and Its Relationship with the Rassi Score. Biomed. Eng. OnLine. 2022, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouchou, F.; Desseilles, M. Heart Rate Variability: A Tool to Explore the Sleeping Brain? Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlstrom, J.; Skog, I.; Handel, P.; Khosrow-Khavar, F.; Tavakolian, K.; Stein, P.K.; Nehorai, A. A Hidden Markov Model for Seismocardiography. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 64, 2361–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuksel, D.; Baker, F.C.; Goldstone, A.; Claudatos, S.A.; Forouzanfar, M.; Prouty, D.E.; Colrain, I.M.; de Zambotti, M. Stress, Sleep, and Autonomic Function in Healthy Adolescent Girls and Boys: Findings from the NCANDA Study. Sleep Health. 2021, 7, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibeira, N.; Maseda, A.; Lorenzo-López, L.; González-Abraldes, I.; López-López, R.; Rodríguez-Villamil, J.L.; Millán-Calenti, J.C. Bright Light Therapy in Older Adults with Moderate to Very Severe Dementia: Immediate Effects on Behavior, Mood, and Physiological Parameters. Healthcare (Basel). 2021, 9, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perneczky, R.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Komossa, K.; Grimmer, T.; Diehl, J.; Kurz, A. Mapping Scores onto Stages: Mini-Mental State Examination and Clinical Dementia Rating. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2006, 14, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, J.H. Eye Protection – Starting from Using the Light Right; Business Weekly Publications: Taipei, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Montaruli, A.; Castelli, L.; Mulè, A.; Scurati, R.; Esposito, F.; Galasso, L.; Roveda, E. Biological Rhythm and Chronotype: New Perspectives in Health. Biomolecules. 2021, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deboer, T. Sleep Homeostasis and the Circadian Clock: Do the Circadian Pacemaker and the Sleep Homeostat Influence Each Other’s Functioning? Neurobiol. Sleep Circadian Rhythms. 2018, 5, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellappa, S.L. Individual Differences in Light Sensitivity Affect Sleep and Circadian Rhythms. Sleep. 2021, 44, zsaa214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirz-Justice, A.; Benedetti, F. Perspectives in Affective Disorders: Clocks and Sleep. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 51, 346–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudreau, P.; Yeh, W.H.; Dumont, G.A.; Boivin, D.B. Circadian Variation of Heart Rate Variability across Sleep Stages. Sleep. 2013, 36, 1919–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, M.A.; Ciraulo, D.A. Bright Light Therapy for Depression: A Review of Its Effects on Chronobiology and the Autonomic Nervous System. Chronobiol. Int. 2014, 31, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.Z.; Cannizzaro, D.N.; Naughton, L.F.; Bove, C. Fluoroquinolones-Associated Disability: It Is Not All in Your Head. Neurosci. 2021, 2, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, P.; Mari, D.; Abbate, C.; Inglese, S.; Bertagnoli, L.; Tomasini, E.; Rossi, P.D.; Lombardi, F. Autonomic Function in Amnestic and Non-amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment: Spectral Heart Rate Variability Analysis Provides Evidence for a Brain-Heart Axis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Mikail, N.; Bengs, S.; Haider, A.; Treyer, V.; Buechel, R.R.; Wegener, S.; Rauen, K.; Tawakol, A.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; et al. Heart-Brain Interactions in Cardiac and Brain Diseases: Why Sex Matters. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3971–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, G.; Favieri, F.; Casagrande, M. Heart Rate Variability and Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.D.; Hoyos, C.M.; Phillips, C.L.; McKinnon, A.C.; Palmer, J.R.; Duffy, S.L.; Mowszowski, L.; Lin, P.; Gordon, C.J.; Naismith, S.L. Left Amygdala Volume Moderates the Relationship between Nocturnal High-Frequency Heart Rate Variability and Verbal Memory Retention in Older Adults with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment: Biomarkers (Non-neuroimaging) / Novel Biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 16, e044608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, K.J.; Cote, K.A. Contributions of Post-learning REM and NREM Sleep to Memory Retrieval. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 59, 101453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.P. The Role of Slow Wave Sleep in Memory Processing. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2009, 5, S20–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordone, S.; Annarumma, L.; Rossini, P.M.; De Gennaro, L. Sleep and β-Amyloid Deposition in Alzheimer Disease: Insights on Mechanisms and Possible Innovative Treatments. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.B.J.; Lai, C.T.; Chen, C.Y.; Lee, G.S.; Yang, C.C.H. Unstable Sleep and Higher Sympathetic Activity during Late-Sleep Periods of Rats: Implication for Late-Sleep-Related Higher Cardiovascular Events. J. Sleep Res. 2013, 22, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).