In 1874 Stoney interpreted Faraday’s laws of electrolysis to mean that “positive as well as negative electricity”, like matter, comprises “indivisible particles” [

1]. He proposed the name “electron” for the “atom of electricity” [

2]. By then it was known that electricity exists in positive and negative types. Thus, in Stoney’s original terminology, electricity comprises discrete positive and negative “electrons”.

With time, Stoney’s “electron” was renamed charge and his atoms of positive and negative electricity came to be known as positive and negative charges. Later, Millikan proved “very directly” [

3] that a quantity of charge consists of individual elementary charges. (The words ‘charge’ and ‘charges’ are hereafter used to describe, respectively, elementary charge and charges). Millikan’s oil drop experiment provides hard evidence that charge, consistent with Stoney’s description, is a particle. Charges behave like infinitesimal, perfectly uniform billiard balls that exist in electrically opposite types. For instance, charges are countable, [

4] storable [

5] and transferable from one object to another. Regardless, the physical nature of the Stoney-Millikan charge is enigmatic [

6,

7,

8]. The mystery is that rest mass (hence volume) defines a physical particle but no one has ever ascertained whether charge, a physical particle on other counts, has rest mass.

In 1897 Thomson discovered a definite physical particle that was finally named “electron”. Accurately, he discovered the negative electron and demonstrated that it has rest mass. (For the sake of clarity, the terms positron and negatron are hereafter used, per the original proposal, [

9] to denote positive and negative electrons respectively and ‘electron’ to denote both). After Thomson’s discovery, Anderson found the positron – proving that electrons, like charges, have positive-negative electric symmetry.

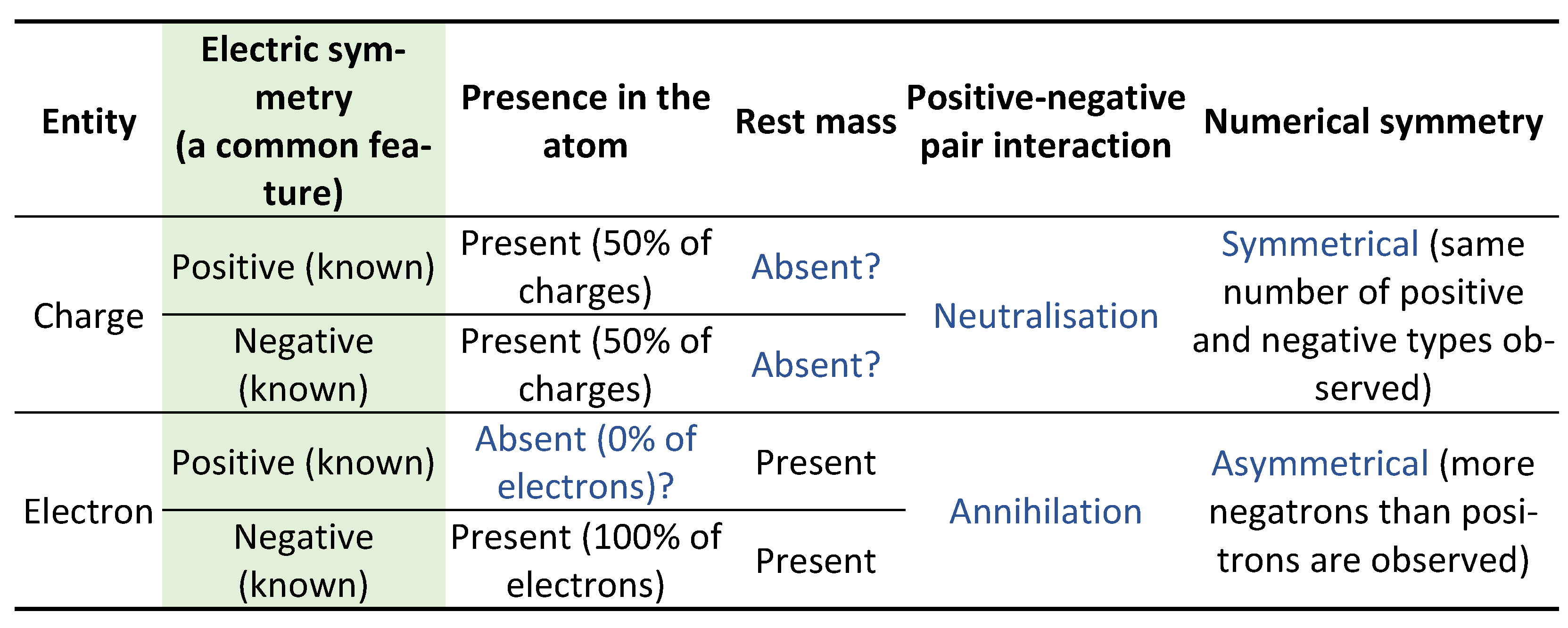

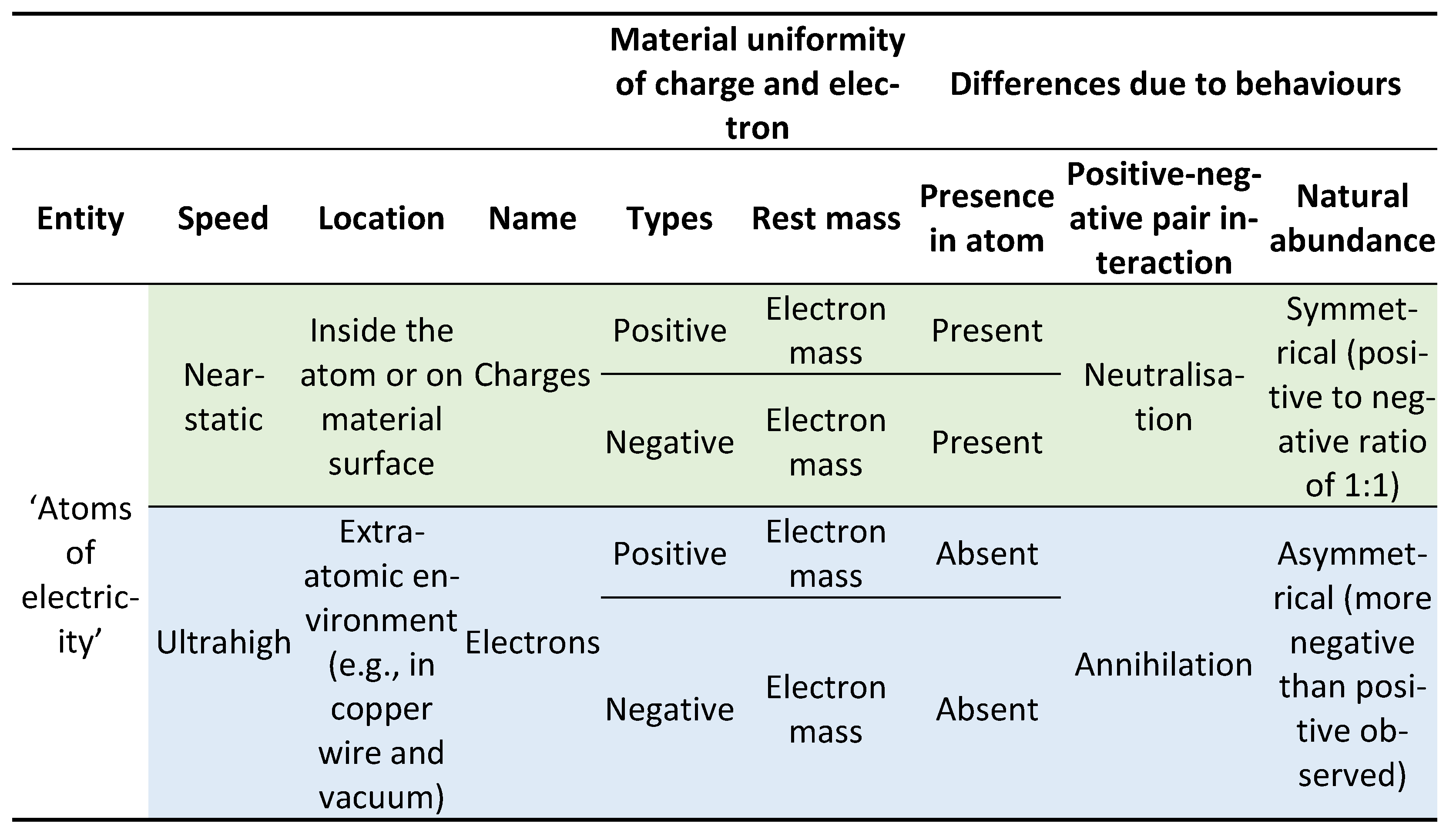

Besides the positive-negative electric symmetry, however, it seemed like ‘positive and negative charges’ and ‘positive and negative electrons’ have nothing in common. The prevailing view is that a charge and an electron are fundamentally different entities that are cojoined in such a way that the comprehensible particle – electron – carries [

10] the incomprehensible charge. The view arises from four considerations (

Table 1). 1) The atomic ratio of negative to positive charges is 1:1; but the atomic ratio of negative to positive electrons is 1:0 – positrons are deemed absent in the atom [

11]. 2) Rest mass defines an electron as a physical particle; but a charge is tacitly considered massless. 3) Opposite electrons annihilate; but opposite charges neutralise. 4) The observational ratio of negative to positive charges is 1:1, resulting in the conservation of electric charge; but by far more negatrons than positrons are observed [

12,

13].

According to CERN, “one of the greatest challenges in physics is to figure out … why we see an asymmetry between matter and antimatter.” [

14]. Notably, negatrons are deemed present in the atom and positron absent [

15]. Further, CERN puts the chances of observing a positron in the environment, instead of a negatron, at one in a billion. Does nature prefer more negatrons than positrons? Or, does it have an equal number of both but, for some reasons, more negatrons that positrons can be observed?

By early 1930s positive beta (β

+) decay was interpreted as evidence that physical positrons exist in the atomic nuclei [

16,

17]. The interpretation was based on the Curie-Joliot inference that proton is a “complex structure” that breaks up into a “positron” and an electrically neutral particle they termed “neutron.” [

18]. That is, a proton (p

+) as a whole is no more an electric object than, for example, a sodium ion (Na

+). Its electric effects stem from a discrete positron that it carries, and which beta decay frees (along with a neutrino), leaving behind the “neutron”. Hence, from the Curie-Joliot deduction, there is a positron on every proton; which can be termed the ‘positron-on-proton’. And since for every proton there is a negatron, the atomic negatron to positron ratio is 1:1.

Elsasser, among others, recognised the Curie-Joliot explanation as “superior to Dirac’s hole theory.” [

19]. Essentially, the explanation means that ‘positron-on-proton’ is an atomic building block – the natural counterpart of the negatron. The view solves an important problem. It was initially thought that proton is the “positive electron” [

20] or negatron’s natural opposite. However, proton is 1,837 times heavier than the negatron. The mass difference disqualifies proton as negatron’s natural counterpart. Prior to the discovery of the actual positive electron, Rutherford wrote, “It might a priori have been anticipated that the positive electron should be the counterpart of the negative electron and have the same small mass. There is, however, not the slightest evidence of the existence of such a counterpart.” [

21].

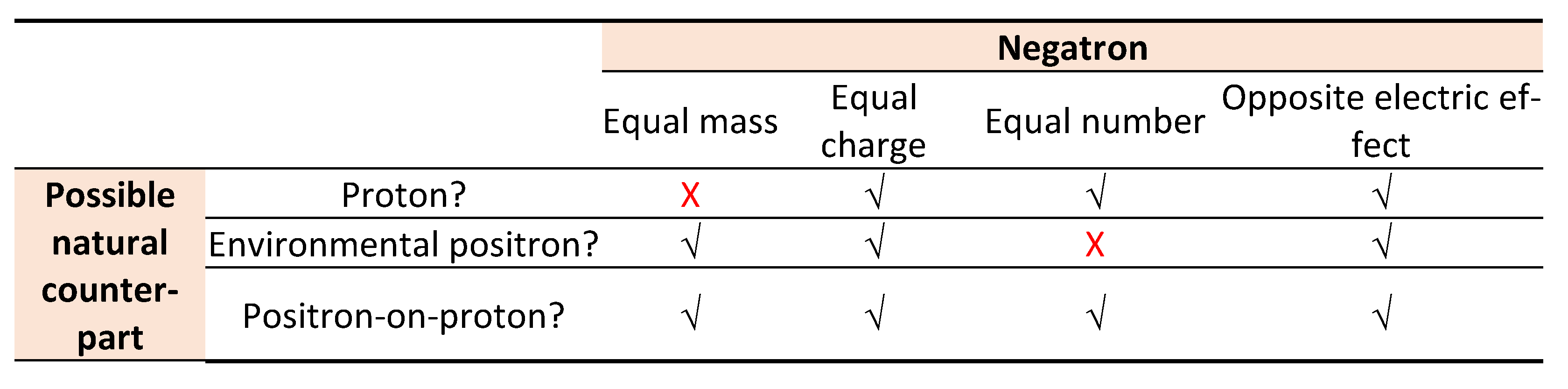

A few years later, “such a counterpart” (positron) with “the same small mass” was found. Still, the positron did not fit as negatron’s natural opposite. Whereas negatron and proton fail to match due to their mass asymmetry, negatron and environment (observable) positron fail to match due to numerical asymmetry. Against these difficulties, the Curie-Joliot positron-on-proton emerges as the negatron’s natural match – equal in mass, in magnitude of charge and in natural abundance; but opposite in electric effects (

Table 2).

Despite its ability to identify positron-on-proton as negatron’s natural match, the Curie-Joliot version of β+ decay was downplayed and finally forgotten. This is because the distinction between positron-on-proton and the environmental positron was missed. If Curie and Joliot described the environmental positron, then their inference contradicts experiment. First, it would imply that positrons and negatrons have a ratio of 1:1, whereas the observable negatrons considerably outnumber positrons. Second, it would imply that opposite electrons coexist in the short intra-atomic distances whereas, empirically, at such short distance a pair of opposite electrons ‘annihilates’ [

22]. But Curie and Joliot described positron-on-proton, not the environmental positron. The difference is significant because positron-on-proton and environmental positron behave differently. Notably, positrons-on-protons and atomic negatrons are numerically equal and interact by pair neutralisation rather than pair annihilation.

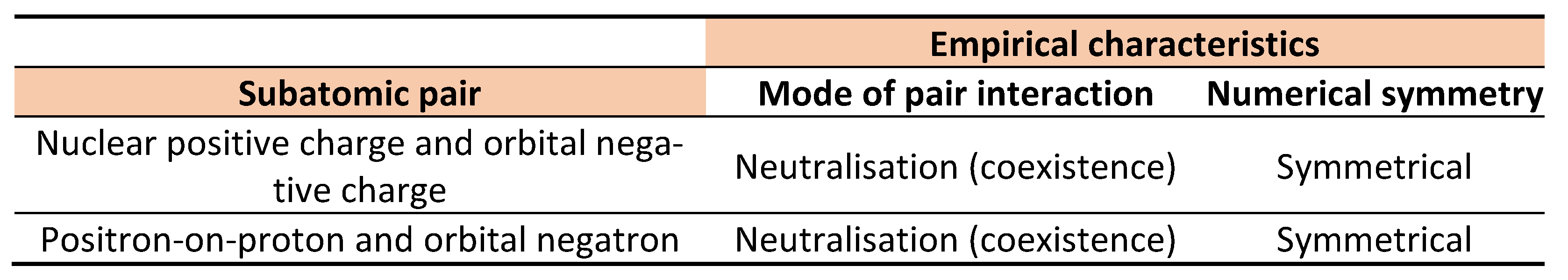

Table 3 shows that positron-on-proton and orbital negatron, respectively, are practically the positive and negative charges. The inevitable inference is that inside the atom electricity is observable as positive and negative charges that are located in the nucleus and orbits respectively. Ejected from the atom, however, electricity is observable as opposite electrons. In other words, charge is the static (nonrelativistic) electron; electron is the ultrahigh speed (relativistic) charge. Collectively, electrons and charges are the same ‘atoms of electricity’; albeit in different states of motion. The inference agrees with observation (

Table 4).

Interpretation of charge as static electron explains, effortlessly, why more negatrons than positrons are observed in our environment. Located in the atomic nuclei, the Curie-Joliot positron-on-proton (positive charge) is heavily shielded by the orbital static negatrons (negative charges) and has negligible chances of escaping to the extra-atomic environment where it can be detected as the usual positron. Put differently, more energy is required to liberate a positive charge (static positron) from the nucleus than to liberate a negative charge (static negatron) from the orbit. However, whether positive or negative, an ‘atom of electricity’ is ejected from the ‘atom of an element’ at tremendous speed, losing the characteristics of a charge and gaining those of an electron. Rutherford (1925) reached the same conclusion when he identified Thomson’s negative electron as “an actual disembodied atom of electricity”. In plain terms, negatron is Stoney’s ‘atom of negative electricity’ detached from the ‘atom of an element’. Conversely, Anderson’s positron is Stoney’s ‘atom of positive electricity’, or the Curie-Joliot positron-on-proton, detached from the ‘atom of an element’. Two pieces of evidence leave no doubt that Rutherford was correct in identifying ‘environmental electron’ as detached (disembodied) ‘atomic charge’.

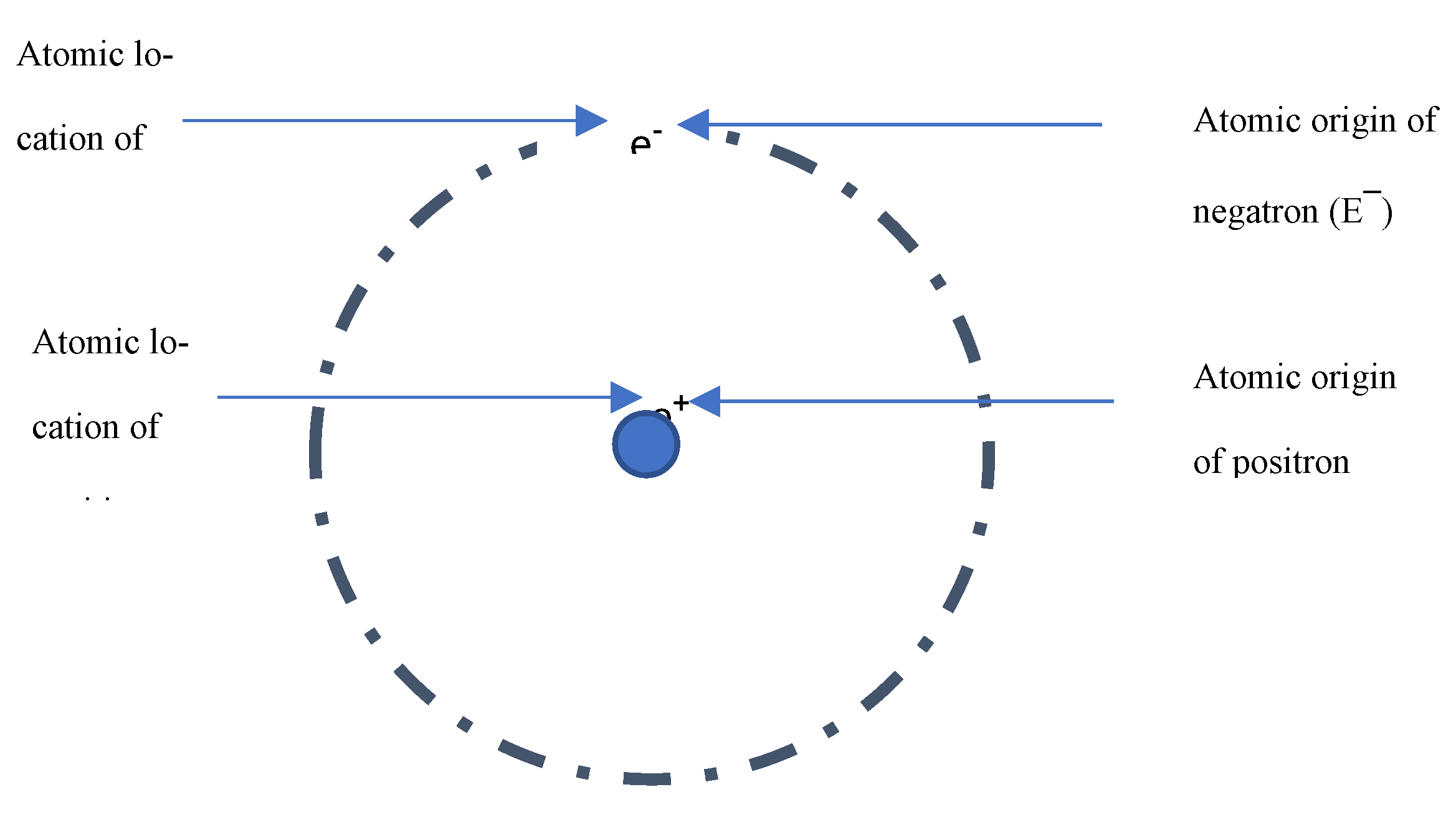

One, negatrons originate from the atomic orbits where Stoney’s negative charges are located. Likewise, Anderson [

23] and Curie [

24] concluded that positrons originate from the atomic nuclei – where Stoney’s positive charges are located (

Figure 1). But charge and electron are inseparable [

25]; nature has neither chargeless (electrically neutral) electron nor electronless (electron-independent) charge. Hence, the same entity identified as a charge within the atom is identified as electron outside the atom.

Two, the historical methods used to investigate electricity reveal that the sole difference between charges and electrons is the speed at which they are observed. Coulomb, Faraday, Millikan, and other ‘electrostatic students’ observed ‘atoms of electricity’ at near-static speeds – in jars, electrolytes, electroscopes, oil drops, glass rods, etc – and recognized them as charges. In contrast, Thomson, Anderson, Dirac [

26] and other ‘electrodynamic students’ observed the same ‘atoms of electricity’ detached from atoms of elements and moving at ultrahigh speed – through vacuumed cathode tubes, conductors and cosmic rays – and recognised them as electrons. Strictly, therefore, electrons – as ultrahigh speed ‘atoms of electricity’ – do not exist inside the atoms. Within the atoms, latent positive and negative electrons coexist as positive-negative charge pairs.

It is here concluded that elementary charge and electron are the same physical particle observed at drastically different speeds. The implication is that static positive and negative electrons (charges) have an equal natural status – both are subatomic building blocks of matter. Positrons are currently considered antimatter particles. Paradoxically, they invariably originate from the atoms of ordinary matter [

27]. Other than their rarity in the environment, which is justified in this article, positrons are fundamentally indistinguishable from negatrons. This finding reveals a new atomic structure.

References

- Wayman, P. A. Stoney’s electron, Europhysics News September/December, p. 159 (1997).

- George Johnstone Stoney 1826–1911, The Daily Express (1911).

- Millikan, R. A. On the elementary electrical charge and the Avogadro Constant, Phys Rev.2.109 (1913).

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Electric charge". Encyclopaedia Britannica, 26 Feb. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/science/electric-charge. Accessed 30 August 2021. 30 August.

- Lüttgens, G., Lüttgens, S., Schubert, W. A. Principles of static electricity. In book: Static Electricity: Understanding, Controlling, Applying (pp.19-39). (2017). [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, J. N. On the nature of electric charge, Int. J. Phys. Sci. 9(4), pp. 54-60, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Etkin, V. A. Modified Coulomb law, World Scientific News 87 163-174, (2017).

- Sus, B. Physical meaning of concepts “electrical charge” and “electric field”, Computational Problems of Electrical Engineering vol. 8, no. 1 (2018).

- Grieder, P. K.F. in Cosmic Rays at Earth, Researcher's Reference Manual and Data Book, pg. 669-891 (2001).

- Marton, L. & Marton, C. Evolution of the concept of the elementary charge, Advances in Electronics and Electron Physics, Vol. 50, pp. 449-472 (1980). [CrossRef]

- Ojovan, M.I. & Lee, W.E. An introduction to nuclear waste immobilization, Second Edition, Elsevier, Amsterdam, p.12. (2014).

- Simak, C.D. (ed.). “From Atom to Infinity, Readings in Modern Science”, p.282 (1964).

- Grimani, C. Upper limit to the cosmic-ray positron flux generated at the pulsar polar cap, 29th International Cosmic Ray Conference, Pune (2005).

- https://home.cern/science/physics/matter-antimatter-asymmetry-problem (accessed 13 November 2022). 13 November.

- Scholtz, J.J., Dijkkamp D.A., & Schmitz, R.W. Secondary electron emission properties, Philips Journal of Research, 50 (3–4), 375-389 (1996). [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C. Controversy and census: nuclear beta decay 1911-1934 (Springer Basel, Ag, 2000).

- Brown, L. M. Nuclear structure and beta decay (1932–1933), American Journal of Physics 56, 982 (1988). [CrossRef]

- Saha, M. N. & Kothari, D.S. A suggested explanation of β-Ray activity, Nature: Letters to the editor (1933). [CrossRef]

- Elsasser, W. A Possible property of the positive electron. Nature 131, 764 (1933). [CrossRef]

- Compton A. H. The elementary particle of positive electricity, Nature, 106, 828-828; (1921). [CrossRef]

- https://doi.org/10.1038/106828a0. [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, E. Electricity and matter, The Scientific Monthly, Vol. 20, No. 2 pp. 121-128 (1925).

- Frolov, A. M. & Farrukh, A. C. Annihilation of the electron-positron pairs in poly-electrons, Journal of Physics A, Mathematical and Theoretical 40(39) (2007). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. The positive electron, Phys. Rev., 43 (6), 491–494 (1933). [CrossRef]

- Curie, I., Joliot F. β-emission of positive electrons, C. R. Acad. Sci. 198, 254 (1934). [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G. The Electron (United States Atomic Energy Commission, Office of Information Services, 1972).

- Dirac, P. A. M. The quantum theory of electron, Proc. R. Soc. London A 117, 610–624 (1928). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).