Submitted:

24 January 2026

Posted:

26 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

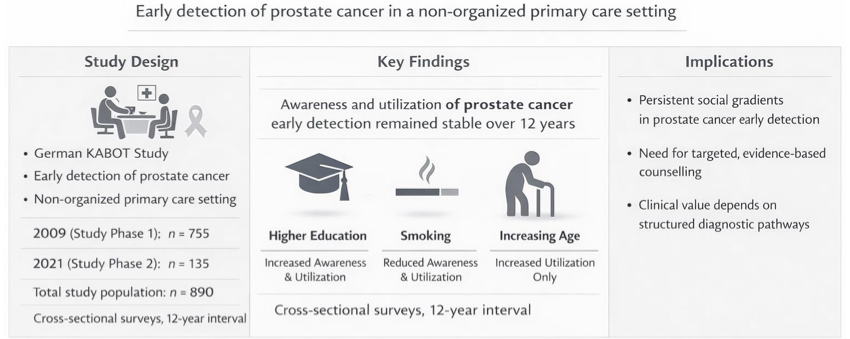

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Implementation of the Study

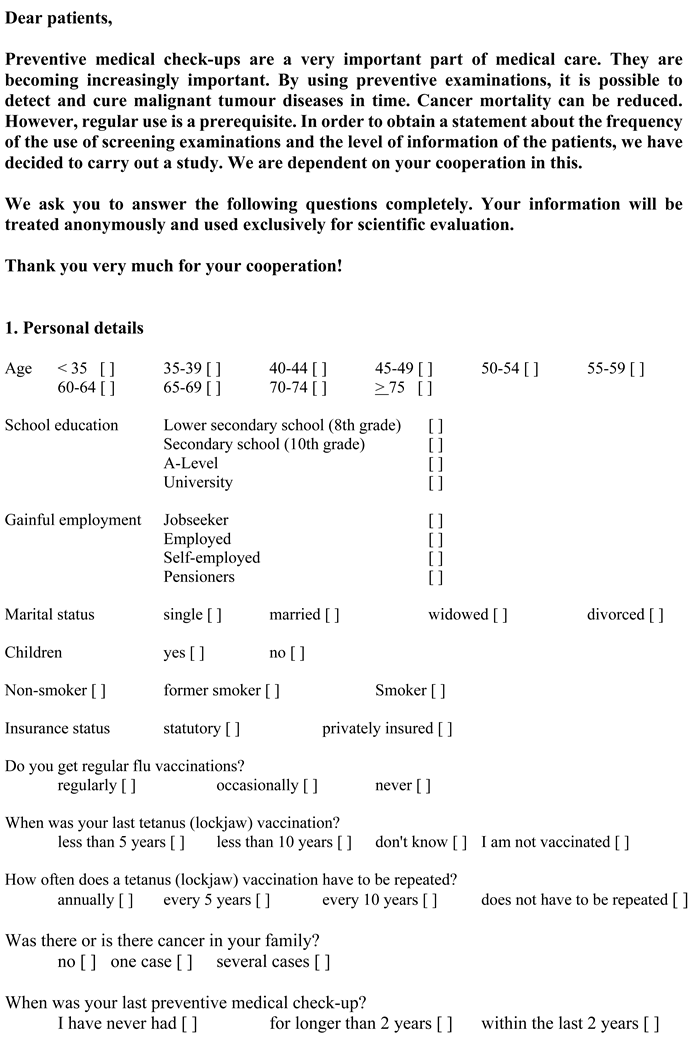

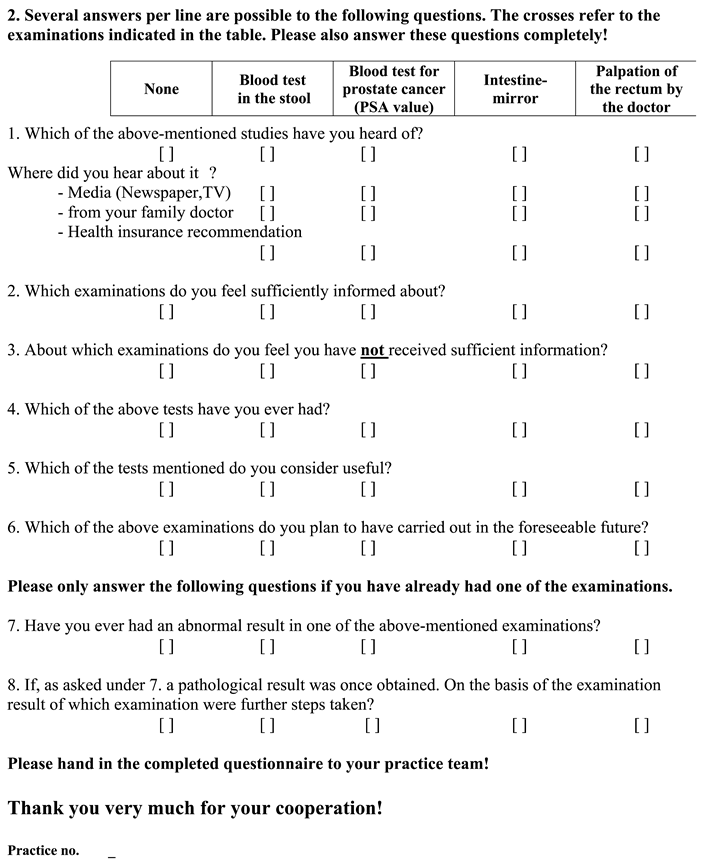

2.2. Structure of the Questionnaires

2.3. Research Questions and Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Awareness of PSA-Based Early Detection

3.3. Utilization of PSA-Based Early Detection

3.4. Subgroup Analysis in Men Aged 45–69 Years

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Clinical Trial Registration

Appendix A

| Section/topic | Item | Item description | Reported on page # |

| Title and abstract | |||

| Title and abstract | 1a | State the word “survey” along with a commonly used term in title or abstract to introduce the study’s design. | AT2 |

| 1b | Provide an informative summary in the abstract, covering background, objectives, methods, findings/results, interpretation/discussion, and conclusions. | AT2 | |

| Introduction | |||

| Background | 2 | Provide a background about the rationale of study, what has been previously done, and why this survey is needed. | AT2 |

| Purpose/aim | 3 | Identify specific purposes, aims, goals, or objectives of the study. | AT2 |

| Methods | |||

| Study design | 4 | Specify the study design in the methods section with a commonly used term (e.g., cross-sectional or longitudinal). | AT2 |

| 5a | Describe the questionnaire (e.g., number of sections, number of questions, number and names of instruments used). | AT2 | |

| Data collection methods | 5b | Describe all questionnaire instruments that were used in the survey to measure particular concepts. Report target population, reported validity and reliability information, scoring/classification procedure, and reference links (if any). | AT2 |

| 5c | Provide information on pretesting of the questionnaire, if performed (in the article or in an online supplement). Report the method of pretesting, number of times questionnaire was pre-tested, number and demographics of participants used for pretesting, and the level of similarity of demographics between pre-testing participants and sample population. | AT2 | |

| 5d | Questionnaire if possible, should be fully provided (in the article, or as appendices or as an online supplement). | AT2 | |

| Sample characteristics | 6a | Describe the study population (i.e., background, locations, eligibility criteria for participant inclusion in survey, exclusion criteria). | AT2 |

| 6b | Describe the sampling techniques used (e.g., single stage or multistage sampling, simple random sampling, stratified sampling, cluster sampling, convenience sampling). Specify the locations of sample participants whenever clustered sampling was applied. | AT2 | |

| 6c | Provide information on sample size, along with details of sample size calculation. | AT2 | |

| 6d | Describe how representative the sample is of the study population (or target population if possible), particularly for population-based surveys. | AT2 | |

| Survey administration |

7a | Provide information on modes of questionnaire administration, including the type and number of contacts, the location where the survey was conducted (e.g., outpatient room or by use of online tools, such as SurveyMonkey). | AT2 |

| 7b | Provide information of survey’s time frame, such as periods of recruitment, exposure, and follow-up days. | AT2 | |

| 7c | Provide information on the entry process: | AT2 | |

| –>For non-web-based surveys, provide approaches to minimize human error in data entry. | |||

| –>For web-based surveys, provide approaches to prevent “multiple participation” of participants. | |||

| Study preparation | 8 | Describe any preparation process before conducting the survey (e.g., interviewers’ training process, advertising the survey). | AT2 |

| Ethical considerations | 9a | Provide information on ethical approval for the survey if obtained, including informed consent, institutional review board approval, Helsinki declaration, and good clinical practice [GCP] declaration (as appropriate). | AT2 |

| 9b | Provide information about survey anonymity and confidentiality and describe what mechanisms were used to protect unauthorized access. | AT2 | |

| Statistical analysis |

10a | Describe statistical methods and analytical approach. Report the statistical software that was used for data analysis. | AT2 |

| 10b | Report any modification of variables used in the analysis, along with reference (if available). | AT2 | |

| 10c | Report details about how missing data was handled. Include rate of missing items, missing data mechanism (i.e., missing completely at random [MCAR], missing at random [MAR] or missing not at random [MNAR]) and methods used to deal with missing data (e.g., multiple imputation). | AT2 | |

| 10d | State how non-response error was addressed. | AT2 | |

| 10e | For longitudinal surveys, state how loss to follow-up was addressed. | AT2 | |

| 10f | Indicate whether any methods such as weighting of items or propensity scores have been used to adjust for non-representativeness of the sample. | AT2 | |

| 10g | Describe any pre-specified subgroup analysis conducted. | AT2 | |

| Results | |||

| Respondent characteristics | 11a | Report numbers of individuals at each stage of the study. Consider using a flow diagram, if possible. | AT2 |

| 11b | Provide reasons for non-participation at each stage, if possible. | AT2 | |

| 11c | Report response rate, present the definition of response rate or the formula used to calculate response rate. | AT2 | |

| 11d | Provide information to define how unique visitors are determined. Report number of unique visitors along with relevant proportions (e.g., view proportion, participation proportion, completion proportion). | AT2 | |

| Descriptive results | 12 | Provide characteristics of study participants, as well as information on potential confounders and assessed outcomes. | AT2 |

| Main findings | 13a | Give unadjusted estimates and, if applicable, confounder-adjusted estimates along with 95% confidence intervals and p-values. | AT2 |

| 13b | For multivariable analysis, provide information on the model building process, model fit statistics, and model assumptions (as appropriate). | AT2 | |

| 13c | Provide details about any pre-specified subgroup analysis performed. If there are considerable amount of missing data, report sensitivity analyses comparing the results of complete cases with that of the imputed dataset (if possible). | AT2 | |

| Discussion | |||

| Limitations | 14 | Discuss the limitations of the study, considering sources of potential biases and imprecisions, such as non-representativeness of sample, study design, important uncontrolled confounders. | AT2 |

| Interpretations | 15 | Give a cautious overall interpretation of results, based on potential biases and imprecisions and suggest areas for future research. | AT2 |

| Generalizability | 16 | Discuss the external validity of the results. | AT2 |

| Other sections | |||

| Role of funding source | 17 | State whether any funding organization has had any roles in the survey’s design, implementation, and analysis. | AT2 |

| Conflict of interest | 18 | Declare any potential conflict of interest. | AT2 |

| Acknowledgements | 19 | Provide names of organizations/persons that are acknowledged along with their contribution to the research. | AT2 |

| Section/Topic | Item | Reported on page # or explanation for non-inclusion |

| Title and abstract | ||

| Title and abstract | 1a | 1 |

| Title and abstract | 1b | 3 |

| Introduction | ||

| Background | 2 | 5 |

| Purpose/Aim | 3 | 7 |

| Methods | ||

| Study design | 4 | 7 |

| Data collection methods | 5a | 9 |

| Data collection methods | 5b | 8 |

| Data collection methods | 5c | 8 and 9 |

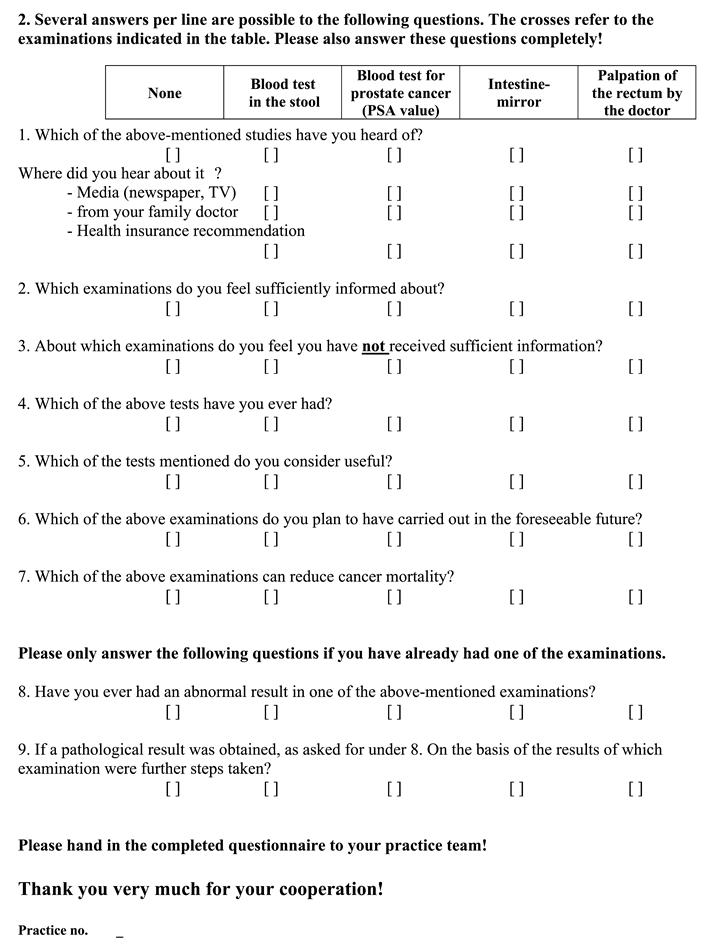

| Data collection methods | 5d | Appendices A1 and A2 |

| Sample characteristics | 6a | 8 |

| Sample characteristics | 6b | 8 |

| Sample characteristics | 6c | The KABOT study fundamentally serves as a hypothesis-generating investigation, thereby lacking precedent studies from other research groups to validate a reliable effect size necessary for biometric sample size calculation. Furthermore, the study employed a highly structured form of cluster sampling in recruiting the study cohort, aiming to motivate the inclusion of approximately 50 patients from all general practitioners within clearly defined regions. This approach, too, posed challenges in conducting a biometric sample size calculation. |

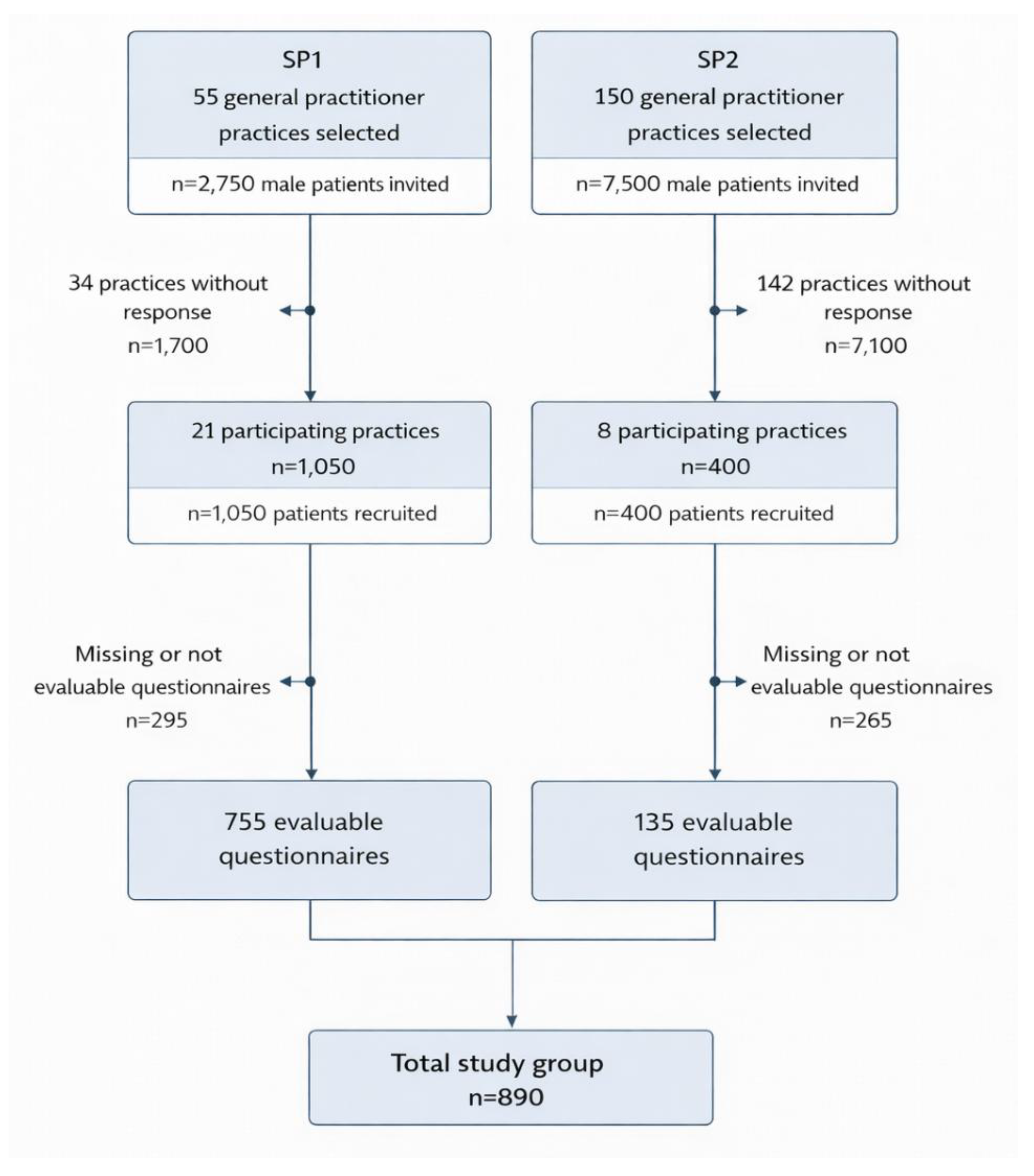

| Sample characteristics | 6d | Throughout both study periods, 29 general practitioners in the Berlin (urban) and Brandenburg (rural) region participated, resulting in the distribution of 1450 questionnaires to eligible male patients. The overall response rate was 61.4% (890/1450), with 72.0% in Study Phase 1 (SP1) and 33.8% in Study Phase 2 (SP2). The ethics approval covered this anonymous, non-interventional survey; participation was voluntary and implied by the return of a completed questionnaire. No data were collected from non-responders (n=560). Accordingly, we were unable to compare characteristics of responders and non-responders and cannot formally assess the representativeness of the responding sample. |

| Survey administration | 7a | 7 and 8 |

| Survey administration | 7b | 8 |

| Survey administration | 7c | The transfer of the entire dataset from the returned questionnaires into the SPSS table used for statistical exploration was independently performed by two members of the research team (KPB and TV). Subsequently, various data entries were identified and cross-checked with patient information in the original questionnaires. This process significantly mitigated the presence of erroneous entries in the final SPSS table utilized for statistical analysis. |

| Study preparation | 8 | 8 and 9 |

| Ethical considerations | 9a | 8 |

| Ethical considerations | 9b | 8 |

| Statistical analysis | 10a | 10 |

| Statistical analysis | 10b | No modification of study variables was conducted. |

| Statistical analysis | 10c | 10 |

| Statistical analysis | 10d | 8 |

| Statistical analysis | 10e | For these analyses, this statement does not apply to the KABOT study. |

| Statistical analysis | 10f | For these analyses, this statement does not apply to the KABOT study. |

| Statistical analysis | 10g | Sensitivity analyses, in the strict sense, were not conducted in this analysis of the KABOT study. However, the validity of the presented results was examined concerning different age groups and also in relation to the patient's insurance status, which was an identified study objective (pre-specified subgroup analysis) |

| Results | ||

| Respondent characteristics | 11a | 10 and 22 |

| Respondent characteristics | 11b | Due to the design of the KABOT study, there are two types of non-responders: |

| 1. The addressed general practitioners, of whom only 29 out of a total of 205 (14.2%) participated in the study despite reminders for their involvement. This is largely attributable to the insufficient density of general practices in the federal state of Brandenburg, where many general practitioners routinely work over 80 hours per week. The extensive workload simply leaves many colleagues with no spare time to support academic research. This observation was undoubtedly exacerbated during Study Phase 2 (SP2) due to the burdens of the COVID-19 pandemic. While 38.2% of the initially addressed general practitioners participated in SP1, this figure dropped to a mere 5.3% in SP2. | ||

| 2. The non-participation of 38.6% of male patients, on the other hand, falls within the expected range as known from other questionnaire-based studies involving patients. The reasons for this are diverse and have been analyzed in numerous studies on the subject. | ||

| Respondent characteristics | 11c | 9 |

| Respondent characteristics | 11d | The response to this item has been documented in Figure 1. Here's a brief summary: 1450 questionnaires were distributed by the 29 general practitioners to 1450 male patients, which were subsequently viewed by these patients. Ultimately, out of these initially 1450 patients, 890 patients (61.4%) opted to participate in the study and returned the completed questionnaires. |

| Descriptive results | 12 | Table 1 |

| Main findings | 13a | The descriptive analyses presented in the KABOT study were unadjusted. |

| Main findings | 13b | For the analyses presented in the KABOT study, this statement does not apply. |

| Main findings | 13c | The handling of non-respondent patients was previously addressed in our response to Item 6d, and the execution of subgroup analyses (as a substitute for sensitivity analyses) was detailed in our response to Item 10g. Among the 890 patients constituting the study group, some of the returned questionnaires were not fully completed for every question (the criterion for questionnaire inclusion was >95% completeness of responses). In Table 1, all missing data in individual questions were labeled as 'not specified,' with missing responses to individual study endpoints ranging between 1 and 12 (equivalent to 0.11% to 1.3%). |

| Discussion | ||

| Limitations | 14 | 15 |

| Interpretations | 15 | 15 and 16 |

| Generalizability | 16 | 12 to 15 |

| Other sections | ||

| Role of funding source | 17 | 17 |

| Conflict of interest | 18 | 17 |

| Acknowledgements | 19 | There are no additional doctors or institutions beyond those listed in the author group who require acknowledgment. A comprehensive acknowledgment was extended to the general practitioners participating over the 12-year study period, as well as to the patients. |

Appendix A1. Questionnaire SP1 (Original Questionnaire in German, Translation for Publication)

Appendix A2. Questionnaire SP2 (Original Questionnaire in German, Translation for Publication)

References

- "Krebs in Deutschland für 2019/2020. 14. Ausgabe. Robert Koch-Institut (Hrsg) und die Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V. (Hrsg). Berlin, 2023." https://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/DE/Content/Publikationen/Krebs_in_Deutschland/krebs_in_deutschland_2023.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. (accessed on 11-Jan-2026).

- "SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Prostate Cancer. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD." https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html. (accessed on 11-Jan-2026).

- Sung, H., J. Ferlay, R. L. Siegel, M. Laversanne, I. Soerjomataram, A. Jemal and F. Bray. "Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries." CA Cancer J Clin 71 (2021): 209-49. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33538338. [CrossRef]

- Bostwick, D. G., H. B. Burke, D. Djakiew, S. Euling, S. M. Ho, J. Landolph, H. Morrison, B. Sonawane, T. Shifflett, D. J. Waters, et al. "Human prostate cancer risk factors." Cancer 101 (2004): 2371-490. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15495199. [CrossRef]

- Dickerman, B. A., S. C. Markt, M. Koskenvuo, E. Pukkala, L. A. Mucci and J. Kaprio. "Alcohol intake, drinking patterns, and prostate cancer risk and mortality: a 30-year prospective cohort study of Finnish twins." Cancer Causes Control 27 (2016): 1049-58. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27351919. [CrossRef]

- Watling, C. Z., R. K. Kelly, Y. Dunneram, A. Knuppel, C. Piernas, J. A. Schmidt, R. C. Travis, T. J. Key and A. Perez-Cornago. "Associations of intakes of total protein, protein from dairy sources, and dietary calcium with risks of colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer: a prospective analysis in UK Biobank." Br J Cancer 129 (2023): 636-47. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37407836. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Y. Zhao, Z. Tao and K. Wang. "Coffee consumption and risk of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis." BMJ Open 11 (2021): e038902. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33431520. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Y., D. M. Yoo, C. Min and H. G. Choi. "Association between Coffee Consumption/Physical Exercise and Gastric, Hepatic, Colon, Breast, Uterine Cervix, Lung, Thyroid, Prostate, and Bladder Cancer." Nutrients 13 (2021): 10.3390/nu13113927. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34836181.

- Perez-Cornago, A., T. J. Key, N. E. Allen, G. K. Fensom, K. E. Bradbury, R. M. Martin and R. C. Travis. "Prospective investigation of risk factors for prostate cancer in the UK Biobank cohort study." Br J Cancer 117 (2017): 1562-71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28910820. [CrossRef]

- Rowles, J. L., 3rd, K. M. Ranard, C. C. Applegate, S. Jeon, R. An and J. W. Erdman, Jr. "Processed and raw tomato consumption and risk of prostate cancer: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis." Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 21 (2018): 319-36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29317772. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., H. Feng, B. Qluwakemi, J. Wang, S. Yao, G. Cheng, H. Xu, H. Qiu, L. Zhu and M. Yuan. "Phytoestrogens and risk of prostate cancer: an updated meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies." Int J Food Sci Nutr 68 (2017): 28-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27687296. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., H. Chen, S. Zhang, X. Chen, Y. Sheng and J. Pang. "Association of cigarette smoking habits with the risk of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis." BMC Public Health 23 (2023): 1150. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37316851. [CrossRef]

- May, M., O. Maurer, S. Lebentrau and S. Brookman-May. "Lower use of prostate specific antigen testing by cigarette smokers-Another possible explanation for the unfavorable prostate cancer (PCA) specific prognosis in smokers?" Cancer Epidemiol 46 (2017): 34-35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28012442. [CrossRef]

- Islami, F., D. M. Moreira, P. Boffetta and S. J. Freedland. "A systematic review and meta-analysis of tobacco use and prostate cancer mortality and incidence in prospective cohort studies." Eur Urol 66 (2014): 1054-64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25242554. [CrossRef]

- Oesterling, J. E. "Prostate specific antigen: a critical assessment of the most useful tumor marker for adenocarcinoma of the prostate." J Urol 145 (1991): 907-23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1707989. [CrossRef]

- Ilic, D., M. M. Neuberger, M. Djulbegovic and P. Dahm. "Screening for prostate cancer." Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013 (2013): CD004720. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23440794. [CrossRef]

- de Vos, A. Meertens, R. Hogenhout, S. Remmers, M. J. Roobol and E. R. S. Group. "A Detailed Evaluation of the Effect of Prostate-specific Antigen-based Screening on Morbidity and Mortality of Prostate Cancer: 21-year Follow-up Results of the Rotterdam Section of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer." Eur Urol 84 (2023): 426-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37029074. [CrossRef]

- Desai, M. M., G. E. Cacciamani, K. Gill, J. Zhang, L. Liu, A. Abreu and I. S. Gill. "Trends in Incidence of Metastatic Prostate Cancer in the US." JAMA Netw Open 5 (2022): e222246. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35285916. [CrossRef]

- Moyer, V. A. and U. S. P. S. T. Force. "Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement." Ann Intern Med 157 (2012): 120-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22801674. [CrossRef]

- Force, U. S. P. S. T., D. C. Grossman, S. J. Curry, D. K. Owens, K. Bibbins-Domingo, A. B. Caughey, K. W. Davidson, C. A. Doubeni, M. Ebell, J. W. Epling, Jr., et al. "Screening for Prostate Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement." JAMA 319 (2018): 1901-13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29801017. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J. A., C. E. Wang, J. C. Lakeman, J. C. Silverstein, C. B. Brendler, K. R. Novakovic, M. S. McGuire and B. T. Helfand. "Primary care physician PSA screening practices before and after the final U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation." Urol Oncol 32 (2014): 41 e23-30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23911680. [CrossRef]

- Frendl, D. M., M. M. Epstein, H. Fouayzi, R. Krajenta, B. A. Rybicki and M. H. Sokoloff. "Prostate-specific antigen testing after the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation: a population-based analysis of electronic health data." Cancer Causes Control 31 (2020): 861-67. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32556947. [CrossRef]

- Kearns, J. T., S. K. Holt, J. L. Wright, D. W. Lin, P. H. Lange and J. L. Gore. "PSA screening, prostate biopsy, and treatment of prostate cancer in the years surrounding the USPSTF recommendation against prostate cancer screening." Cancer 124 (2018): 2733-39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29781117. [CrossRef]

- Halpern, J. A., C. Oromendia, J. E. Shoag, S. Mittal, M. F. Cosiano, K. V. Ballman, A. J. Vickers and J. C. Hu. "Use of Digital Rectal Examination as an Adjunct to Prostate Specific Antigen in the Detection of Clinically Significant Prostate Cancer." J Urol 199 (2018): 947-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29061540. [CrossRef]

- "Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): S3-Leitlinie Prostatakarzinom, Langversion 6.2, 2021, AWMF Registernummer: 043/022OL" http://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/prostatakarzinom/. (accessed on 11-Jan-2026).

- Bailey, J. A., A. J. Morton, J. Jones, C. J. Chapman, S. Oliver, J. R. Morling, H. Patel, A. Banerjea and D. J. Humes. "Sociodemographic variations in the uptake of faecal immunochemical tests in primary care: a retrospective study." Br J Gen Pract 73 (2023): e843-e49. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37845084. [CrossRef]

- Golijanin, B., V. Bhatt, A. Homer, K. Malshy, A. Ochsner, R. Wales, S. Khaleel, A. Mega, G. Pareek and E. Hyams. ""Shared decision-making" for prostate cancer screening: Is it a marker of quality preventative healthcare?" Cancer Epidemiol 88 (2024): 102492. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/38056246. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. A., R. P. Moser, G. L. Ellison and D. N. Martin. "Associations of Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) Testing in the US Population: Results from a National Cross-Sectional Survey." J Community Health 46 (2021): 389-98. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33064229. [CrossRef]

- Littlejohns, T. J., R. C. Travis, T. J. Key and N. E. Allen. "Lifestyle factors and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in UK Biobank: Implications for epidemiological research." Cancer Epidemiol 45 (2016): 40-46. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27693812. [CrossRef]

- Mondragon Marquez, L. I., D. L. Dominguez Bueso, L. M. Gonzalez Ruiz and J. J. Liu. "Associations between sociodemographic factors and breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening in the United States." Cancer Causes Control 34 (2023): 1073-84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37486400. [CrossRef]

- Nair-Shalliker, V., A. Bang, M. Weber, D. E. Goldsbury, M. Caruana, J. Emery, E. Banks, K. Canfell, D. L. O'Connell and D. P. Smith. "Factors associated with prostate specific antigen testing in Australians: Analysis of the New South Wales 45 and Up Study." Sci Rep 8 (2018): 4261. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29523809. [CrossRef]

- Pickles, K., L. D. Scherer, E. Cvejic, J. Hersch, A. Barratt and K. J. McCaffery. "Preferences for More or Less Health Care and Association With Health Literacy of Men Eligible for Prostate-Specific Antigen Screening in Australia." JAMA Netw Open 4 (2021): e2128380. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34636915. [CrossRef]

- Trinh, Q. D., H. Li, C. P. Meyer, J. Hanske, T. K. Choueiri, G. Reznor, S. R. Lipsitz, A. S. Kibel, P. K. Han, P. L. Nguyen, et al. "Determinants of cancer screening in Asian-Americans." Cancer Causes Control 27 (2016): 989-98. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27372292. [CrossRef]

- Vogelaar, I., M. van Ballegooijen, D. Schrag, R. Boer, S. J. Winawer, J. D. F. Habbema and A. G. Zauber. "How much can current interventions reduce colorectal cancer mortality in the U.S.?" Cancer 107 (2006): 1624-33. https://acsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/cncr.22115. [CrossRef]

- Kohar, A., S. M. Cramb, K. Pickles, D. P. Smith and P. D. Baade. "Changes in prostate specific antigen (PSA) "screening" patterns by geographic region and socio-economic status in Australia: Analysis of medicare data in 50-69 year old men." Cancer Epidemiol 83 (2023): 102338. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36841020. [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, S. V., A. Krilaviciute, R. Al-Monajjed, P. Seibold, M. Kuczyk, J. E. Gschwend, J. Debus, G. Antoch, L. Schimmoller, H. P. Schlemmer, et al. "Risk-adapted Prostate Cancer Screening Achieves Mammography-like Benefits: Evidence and Implications for Europe." Eur Urol (2025): 10.1016/j.eururo.2025.12.002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/41419391.

- Albers, P., A. Krilaviciute, P. Seibold, M. de Vrieze, J. Lakes, M. A. Kuczyk, N. N. Harke, J. Debus, C. A. Grott, J. E. Gschwend, et al. "Do We Need Early Detection of Grade Group 2 Prostate Cancer in a Screening Program for Young Men? Results from the PROBASE Screening Trial." Eur Urol Oncol (2025): 10.1016/j.euo.2025.06.007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40640052.

- Boschheidgen, M., P. Albers, H. P. Schlemmer, S. Hellms, D. Bonekamp, A. Sauter, B. Hadaschik, A. Krilaviciute, J. P. Radtke, P. Seibold, et al. "Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Prostate Cancer Screening at the Age of 45 Years: Results from the First Screening Round of the PROBASE Trial." Eur Urol 85 (2024): 105-11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37863727. [CrossRef]

- "Kassenärztliche Vereinigung Brandenburg: Arztsuche. Available online." https://arztsuche.kvbb.de/ases-kvbb/. (accessed on 11-Jan-2026).

- "Kassenärztliche Vereinigung Brandenburg: KV Regiomed Lehrpraxen." https://www.kvbb.de/praxiseinstieg/studium-weiterbildung/kv-regiomed-lehrpraxis. (accessed on 11-Jan-2026).

- "Deutsches Register klinischer Studien." https://drks.de/search/de. (accessed on 11-Jan-2026).

- Sharma, A., N. T. Minh Duc, T. Luu Lam Thang, N. H. Nam, S. J. Ng, K. S. Abbas, N. T. Huy, A. Marusic, C. L. Paul, J. Kwok, et al. "A Consensus-Based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS)." J Gen Intern Med 36 (2021): 3179-87. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33886027. [CrossRef]

- Bretthauer, M., P. Wieszczy, M. Loberg, M. F. Kaminski, T. F. Werner, L. M. Helsingen, Y. Mori, O. Holme, H. O. Adami and M. Kalager. "Estimated Lifetime Gained With Cancer Screening Tests: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials." JAMA Intern Med 183 (2023): 1196-203. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37639247. [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A., S. A. Fedewa, J. Ma, R. Siegel, C. C. Lin, O. Brawley and E. M. Ward. "Prostate Cancer Incidence and PSA Testing Patterns in Relation to USPSTF Screening Recommendations." JAMA 314 (2015): 2054-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26575061. [CrossRef]

- Miller, A., J. Yates, M. M. Epstein, J. Fantasia, D. Frendl, A. Afiadata, M. Sokoloff and R. Luckmann. "Impact of 2012 USPSTF Screening PSA Guideline Statement: Changes in Primary Care Provider Practice Patterns and Attitudes." Urol Pract 4 (2017): 126-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37592666. [CrossRef]

- Patel, N. H., J. Bloom, J. Hillelsohn, S. Fullerton, D. Allman, G. Matthews, M. Eshghi and J. L. Phillips. "Prostate Cancer Screening Trends After United States Preventative Services Task Force Guidelines in an Underserved Population." Health Equity 2 (2018): 55-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29806045. [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A., M. B. Culp, J. Ma, F. Islami and S. A. Fedewa. "Prostate Cancer Incidence 5 Years After US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations Against Screening." J Natl Cancer Inst 113 (2021): 64-71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32432713. [CrossRef]

- Logan, C. D., A. K. Mahenthiran, M. R. Siddiqui, D. D. French, M. T. Hudnall, H. D. Patel, A. B. Murphy, J. A. Halpern and D. J. Bentrem. "Disparities in access to robotic technology and perioperative outcomes among patients treated with radical prostatectomy." J Surg Oncol 128 (2023): 375-84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37036165. [CrossRef]

- Nemirovsky, D. R., C. Klose, M. Wynne, B. McSweeney, J. Luu, J. Chen, M. Atienza, B. Waddell, B. Taber, S. Haji-Momenian, et al. "Role of Race and Insurance Status in Prostate Cancer Diagnosis-to-Treatment Interval." Clin Genitourin Cancer 21 (2023): e198-e203. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36653224. [CrossRef]

| SP1 (n= 755) | SP2 (n= 135) | Total (n= 890) | p-value | |||||

| n | Percentage | n | Percentage | n | Percentage | |||

| Age | <35 | 29 | 3.8% | 2 | 1.5% | 31 | 3.5% | .068 |

| 35–39 | 38 | 5.0% | 7 | 5.2% | 45 | 5.1% | ||

| 40–44 | 43 | 5.7% | 8 | 5.9% | 51 | 5.7% | ||

| 45–49 | 61 | 8.1% | 7 | 5.2% | 68 | 7.6% | ||

| 50–54 | 86 | 11.4% | 15 | 11.1% | 101 | 11.3% | ||

| 55–59 | 120 | 15.9% | 21 | 15.6% | 141 | 15.8% | ||

| 60–64 | 70 | 9.3% | 15 | 11.1% | 85 | 9.6% | ||

| 65–69 | 126 | 16.7% | 22 | 16.3% | 148 | 16.6% | ||

| 70–74 | 117 | 15.5% | 14 | 10.4% | 131 | 14.7% | ||

| From 75 | 64 | 8.5% | 21 | 15.6% | 85 | 9.6% | ||

| Not specified | 1 | 0.1% | 3 | 2.2% | 4 | 0.4% | ||

| School education | Basic Secondary School Qualification | 199 | 26.4% | 14 | 10.4% | 213 | 23.9% | .002 |

| Secondary school | 276 | 36.6% | 55 | 40.7% | 331 | 37.2% | ||

| Higher school | 44 | 5.8% | 8 | 5.9% | 52 | 5.8% | ||

| University degree | 230 | 30.5% | 52 | 38.5% | 282 | 31.7% | ||

| Not specified | 6 | 0.8% | 6 | 4.4% | 12 | 1.3% | ||

| Employment status | Jobseeker | 62 | 8.2% | 5 | 3.7% | 67 | 7.5% | <.001 |

| Employed | 273 | 36.2% | 7 | 5.2% | 280 | 31.5% | ||

| Self-employed | 37 | 4.9% | 61 | 45.2% | 98 | 11.0% | ||

| Pensioner | 374 | 49.5% | 58 | 43.0% | 432 | 48.5% | ||

| Not specified | 9 | 1.2% | 4 | 3.0% | 13 | 1.5% | ||

| Family cancer history | no | 395 | 52.3% | 61 | 45.2% | 456 | 51.2% | .102 |

| One case | 241 | 31.9% | 43 | 31.9% | 284 | 31.9% | ||

| several cases | 106 | 14.0% | 28 | 20.7% | 134 | 15.1% | ||

| Not specified | 13 | 1.7% | 3 | 2.2% | 16 | 1.8% | ||

| Children | Yes | 645 | 85.4% | 108 | 80.0% | 753 | 84.6% | .019 |

| No | 98 | 13.0% | 24 | 17.8% | 122 | 13.7% | ||

| Not specified | 12 | 1.6% | 3 | 2.2% | 15 | 1.7% | ||

| Smokers | Non-smoker | 366 | 48.5% | 85 | 63.0% | 451 | 50.7% | <.001 |

| Former smoker | 231 | 30.6% | 18 | 13.3% | 249 | 28.0% | ||

| Smoker | 155 | 20.5% | 29 | 21.5% | 184 | 20.7% | ||

| Not specified | 3 | 0.4% | 3 | 2.2% | 6 | 0.7% | ||

| Insurance status | Statutory | 700 | 92.7% | 118 | 87.4% | 818 | 91.9% | .344 |

| Private | 50 | 6.6% | 13 | 9.6% | 63 | 7.1% | ||

| Not specified | 5 | 0.7% | 4 | 3.0% | 9 | 1.0% | ||

| Influencing factor | univariate logistic regression | multivariate logistic regression | ||||||

| Odds-ratio | 95%-confidence interval | p-value | Odds-ratio | 95%-confidence interval | p-value | |||

| Study phase | 1.028 | .699 | 1.513 | .888 | 1.021 | .664 | 1.571 | .924 |

| Age | 1.063 | 1.005 | 1.124 | .032 | .990 | .926 | 1.058 | .766 |

| School education | 2.021 | 1.496 | 2.730 | <.001 | 1.709 | 1.239 | 2.357 | .001 |

| Smoking | .553 | .397 | .770 | <.001 | .688 | .479 | .989 | .043 |

| Paternity | 2.081 | 1.414 | 3.064 | <.001 | 1.939 | 1.249 | 3.012 | .003 |

| Employment status | 1.829 | 1.108 | 3.018 | .018 | 1.528 | .888 | 2.631 | .126 |

| History of cancer in family | 1.210 | .915 | 1.599 | .182 | 1.137 | .844 | 1.531 | .397 |

| Insurance | 1.556 | .893 | 2.711 | .119 | 1.281 | .711 | 2.305 | .410 |

| Influencing factor | univariate logistic regression | multivariate logistic regression | ||||||

| Odds-ratio | 95%-confidence interval | p-value | Odds-ratio | 95%-confidence interval | p-value | |||

| Study phase | 1.476 | 1.022 | 2.131 | .038 | 1.365 | .885 | 2.105 | .160 |

| Age | 1.417 | 1.327 | 1.513 | <.001 | 1.391 | 1.291 | 1.498 | <.001 |

| School education | 1.873 | 1.422 | 2.469 | <.001 | 1.632 | 1.190 | 2.239 | .002 |

| Smoking | .378 | .264 | .541 | <.001 | .608 | .405 | .912 | .016 |

| Paternity | 2.646 | 1.718 | 4.076 | <.001 | 1.327 | .793 | 2.239 | .282 |

| Employment status | 2.473 | 1.402 | 4.362 | .002 | .981 | .525 | 1.831 | .951 |

| History of cancer in family | 1.147 | .0877 | 1.498 | .316 | 1.197 | .884 | 1.622 | .245 |

| Insurance | 1.085 | .669 | 1.761 | .741 | 1.314 | .751 | 2.299 | .338 |

| Influencing factor | univariate logistic regression | multivariate logistic regression | ||||||

| Odds-ratio | 95%-confidence interval | p-value | Odds-ratio | 95%-confidence interval | p-value | |||

| Study phase | 1.287 | .747 | 2.217 | .363 | 1.252 | .693 | 2.262 | .456 |

| Age | .987 | .862 | 1.130 | .845 | .924 | .795 | 1.075 | .308 |

| School education | 1.875 | 1.258 | 2.794 | .002 | 1.717 | 1.113 | 2.647 | .014 |

| Smoking | .525 | .343 | .804 | .003 | .595 | .375 | .945 | .028 |

| Paternity | 1.665 | .930 | 2.981 | .086 | 1.707 | .891 | 3.271 | .107 |

| Employment status | 1.429 | .750 | 2.722 | .278 | 1.311 | .664 | 2.586 | .435 |

| History of cancer in family | 1.255 | .864 | 1.825 | .233 | 1.113 | .747 | 1.660 | .599 |

| Insurance | 1.413 | .710 | 2.811 | .325 | 1.025 | .495 | 2.122 | .946 |

| Influencing factor | univariate logistic regression | multivariate logistic regression | ||||||

| Odds-ratio | 95%-confidence interval | p-value | Odds-ratio | 95%-confidence interval | p-value | |||

| Study phase | 1.350 | .838 | 2.175 | .217 | 1.227 | .717 | 2.098 | .455 |

| Age | 1.528 | 1.338 | 1.745 | <.001 | 1.520 | 1.315 | 1.757 | <.001 |

| School education | 1.879 | 1.322 | 2.670 | <.001 | 1.590 | 1.077 | 2.347 | .020 |

| Smoking | .469 | .307 | .716 | <.001 | .627 | .393 | 1.001 | .051 |

| Paternity | 1.320 | .748 | 2.330 | .338 | .934 | .484 | 1.803 | .838 |

| Employment status | 1.708 | .901 | 3.236 | .101 | 1.073 | .543 | 2.123 | .839 |

| History of cancer in family | 1.284 | .914 | 1.803 | .150 | 1.382 | .949 | 2.014 | .092 |

| Insurance | 1.153 | .645 | 2.059 | .632 | 1.136 | .594 | 2.170 | .700 |

| Author | Study Period | Region | Number of participants | Question | Factors with a significant impact on the endpoint | |

| Johnson et al. [28] | 2010 and 2015 | USA | 15,372 | Had PSA testing | Survey year, Nativity, Region, Age, Education, Martial status, Insurance, Family history, Age, Race/ethnicity | |

| Pickles et al. [32] | 2018 | Australia | 2,993 | Preference for health care regarding PSA-based ED | Education, Health literacy | |

| Littlejohns et al. [29] | 2006-2010 | UK | 212,039 | Had PSA testing | Age, Townsend deprivation score, Region, Family history of cancer, Ethnicity, Employment, Lives with a wife or partner, Smoking, Alcohol intake, Standing high, Private healthcare, Vasectomy, Diabetes (self-reported), Heart disease (self-reported), Hypertension (self-reported), Stroke (self-reported) | |

| Golijanin et al. [27] | 2020 | USA | 56,801 | Shared decision-making, Talked about PSA, Had PSA testing | Age, Racial disparities, Shared decision-making, Smoking, Colonoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy, Stool test, Insurance, Regular exercise, Vaccinating | |

| Cohn et al. [21] | 2007 and 2012 | USA | 112,221 | Had PSA testing | Survey year, Age, Previous PSA value | |

| Frendl et al. [22] | 2000-2014 | USA | 253,139 | Receiving >1 PSA-test per year | Time period, Age | |

| Nair-Shalliker et al. [31] | 2012-2014 | Australia | 62,765 | Had PSA testing | Number of general practitioner consultations, Treatment of Benign prostatic hyperplasia, Age, Household income, Living area, Education, Lives with wife or partner, Insurance, Region of birth, Number of medications, Stool test, Overall health, Quality of life, Psychosocial distress, Family history of cancer, Diabetes, Overweight, Alcohol, Physical activity, Urinary bother, Smoking, Erectile dysfunction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.