1. Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. Pn) is a Gram-positive, encapsulated bacterium and a major cause of an array of diseases such as pneumonia, acute otitis media and meningitis. Transmission generally occurs through direct person-to-person contact via respiratory droplets through coughing and sneezing. In addition, people can be carrier without becoming unwell and possibly spread the bacteria to others. It is estimated that world-wide approximately one million children die every year due to S. Pn. [

1]. In Egypt, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates 6,500 deaths from S.Pn in 2021. Many of these deaths can be prevented through vaccination. The 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) protects against 13 types of the S. Pn. bacteria and has an effectiveness of around 45% for all-cause pneumonia [

2]. PCV13 therefore can reduce morbidity and mortality, and as a consequence related economic effects such as health care costs.

Vaccinating against S. Pn. leads to a range of positive impacts, however it also entails costs. These include vaccine procurement, program coordination and the resources required for vaccine introduction into the routine immunization program. It is therefore essential to understand the expected health and economic effects before introducing the vaccine. Experiences in other countries show that PCV introduction consistently leads to substantial health gains, with evaluations reporting ~860 deaths averted per year in childhood-focused models [

3], and ~2,490 deaths per year in a 100-year modelling horizon [

4]. Global evidence in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) further suggests 1,000–1,800 preventable deaths annually for countries of Egypt’s size (116 million in 2024) [

5], and demonstrates that PCV programs are highly cost-effective, with ICERs typically 0.2–0.6 × GDP per capita [

6].

Vaccinations against S. Pn are not currently part of Egypt's National Immunization Program. The decision to introduce was initially encouraged by a national cost-effectiveness analysis conducted by Sibak et al in 2013 [

3], which found PCV13 to be cost-effective (USD 3,916 per DALY averted). The 2013 national cost-effectiveness analysis is now outdated, having used earlier disease burden estimates and willingness-to-pay thresholds and omitted indirect (herd immunity) effects. Since then, the decision context has also shifted. In December 2021, the Egyptian President issued a directive to establish the Vaccines and Biotechnology City in Egypt, to strengthen domestic vaccine production [

7]. PCV13 was identified as one of the priorities for domestic production. In parallel Egypt can leverage external financing and technical support from the Gavi Alliance middle-income country scheme and UNICEF procurement mechanisms, creating near-term options for vaccine introduction while domestic capacity is developed [

8]. Against this backdrop, updated economic evidence is needed to inform a time-sensitive choice among plausible introduction and supply pathways. Decision-makers must weigh (i) introduction via continued procurement through UNICEF (with temporary Gavi support where applicable), (ii) a phased transition from imported to domestically produced PCVs, and (iii) alternative product pathways (PCV10 initially, with later switch to PCV13), recognizing that establishing local production typically requires 5–10 years [

9,

10]. This study therefore updates and extends the earlier national analysis to reflect current epidemiology, costs and Egyptian industrial development priorities. Further, the timing, affordability, and economic value of PCV introduction is compared under these alternative procurement and domestic manufacturing scenarios.

To do this, the cost-effectiveness, return on investment, and budget impact of introducing PCV for children under five versus no vaccination is assessed. Cost-effectiveness results summarise the cost per health gain, while ROI results capture the broader economic returns associated with reduced disease burden. Budget impact results summarise the expected financing implications for government and other payers, informing affordability and sustainability under constrained health budgets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

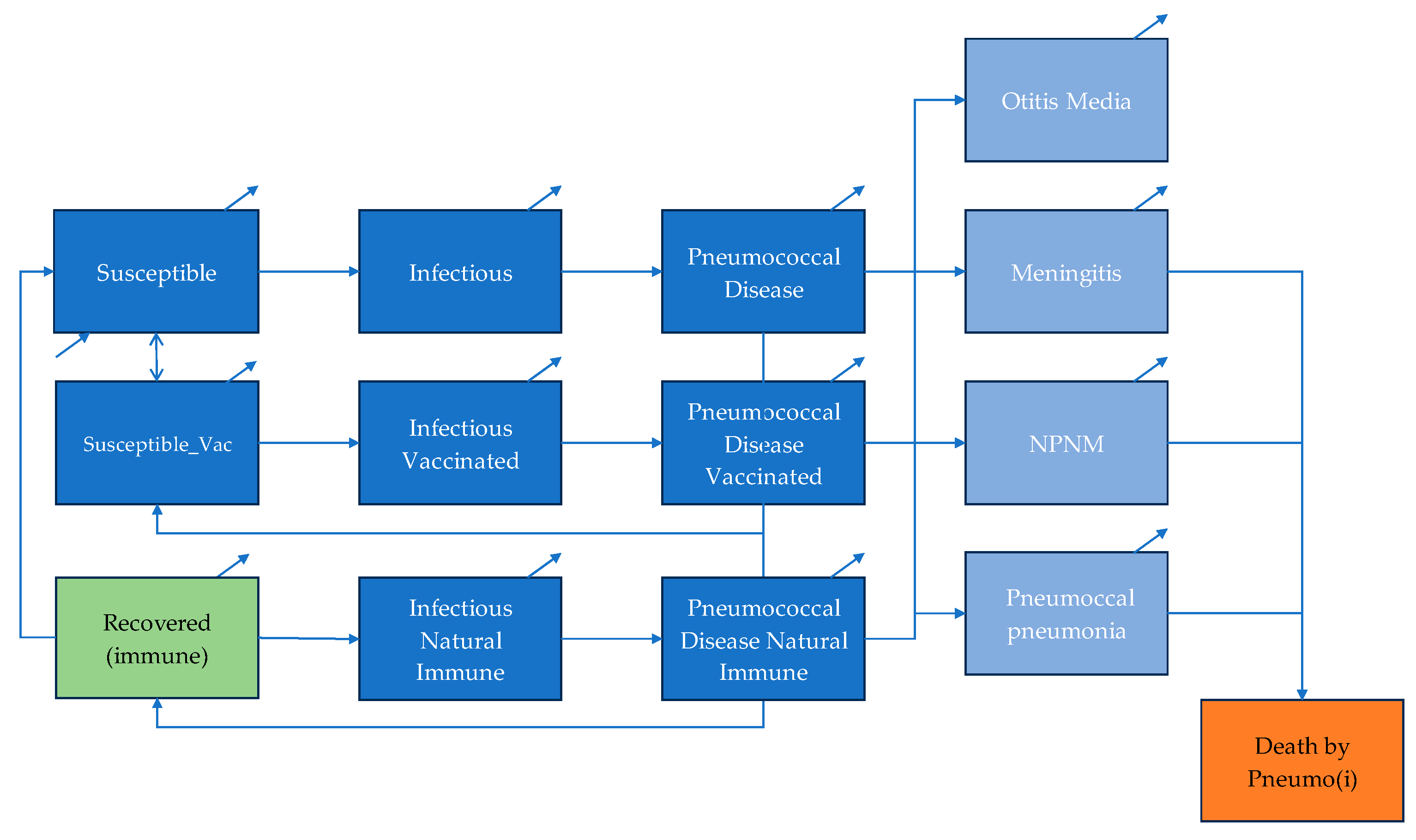

The analysis was structured and reported in accordance with the CHEERS 2022 guidelines for health economic evaluations [

11]. The cost-effectiveness of PCV introduction in Egypt from a health system perspective was studied. An age-structured, dynamic compartmental model was developed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of introducing PCV in Egypt over a 20-year time horizon. The model simulates pneumococcal transmission and disease progression across the entire population and was selected to capture both direct effects in children and indirect (herd immunity) effects in individuals aged >5 years, as well as the way these effects evolve following vaccine introduction. The core transmission component follows a standard SIRD framework (Susceptible–Infectious–Recovered–Death) [

12], in which the number of new infections depends on the interaction between susceptible and infectious individuals. The model was adapted to reflect the epidemiology of

Streptococcus pneumoniae and the mechanism of vaccine-derived protection. The population is divided into three immunity groups: susceptible unvaccinated, susceptible vaccinated, and recovered-immune. Individuals in each group progress through the same health state, susceptible, infectious, disease and either recovery or death. Natural immunity following infection provides partial protection, while vaccine-induced immunity confers higher protection [

13,

14]. Both forms of immunity wane over time, allowing individuals to return to the susceptible pool.

The disease state is disaggregated into four pneumococcal syndromes: acute otitis media (AOM), pneumococcal pneumonia, meningitis and non-pneumonia non-meningitis (NPNM) invasive disease, including sepsis. Age-specific incidence, case fatality and severity parameters determine transitions between infectious and disease states. Long-term sequelae were not specifically included to keep model outcomes conservative. Demographic processes, including births and background mortality, are incorporated to reflect population turnover and maintain epidemiological dynamics over the 20-year time frame. A schematic illustration of the transmission pathways, immunity transitions and disease compartments is presented in

Figure 1.

2.2. Dynamic Transmission Model

The dynamic transmission component operates across three age groups (0–4 years, 5–64 years and ≥65 years). Age-specific transmission patterns were modelled using a contact matrix derived from Prem et. al. [

15], adjusted to reflect the demographic structure of Egypt. The force of infection in each age group depends on the number of susceptible individuals and the number of infectious carriers (vaccinated, unvaccinated and recovered-immune), weighted by age-specific contact rates.

The transmission dynamics are governed by a system of differential equations that simulate transitions between susceptibility, infection and recovery for vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals (

Appendix A provides transmission and progression equations).

2.3. Model Assumptions and Analytical Framework

Table 1 summarizes the core modelling assumptions underpinning the economic evaluation, including the model type, analytic perspective, time horizon, discount rate and comparator. Economic parameters were selected to reflect Egypt’s health financing context and follow international guidance. Both PCV10 and PCV13 were included because they have substantially different price points but broadly similar effectiveness profiles, as noted by WHO SAGE [

16]. Evaluating both products enabled assessment of how vaccine pricing influences cost-effectiveness. The eligible population—children from birth to one year—follows WHO-recommended schedules for pneumococcal vaccination [

17]. A 3-dose vaccine schedule was analyzed without a booster (3+0), reflecting a pragmatic schedule for early implementation and following guidance from UNICEF. Vaccine coverage assumptions were based on historical DTP3 coverage in Egypt and validated with UNICEF Egypt data, ensuring realistic projections of PCV uptake.

A healthcare payer perspective was adopted because pneumococcal vaccine procurement and delivery are financed primarily through government budgets in Egypt, consistent with prior PCV evaluations in LMIC settings [

3,

4]. Direct medical costs were therefore used to reflect decision-relevant budgetary impacts. A 20-year time horizon was used to capture the long-term health and economic consequences of vaccine introduction, including the gradual accumulation of both direct and indirect effects. Future costs and outcomes were discounted at an annual rate of 3.5%, in line with local economic evaluation guidelines [

18]. Egypt-specific willingness-to-pay thresholds were applied to provide contextually appropriate interpretation of cost-effectiveness [

19].

Table 2 summarises the epidemiological, clinical and vaccine-related parameters incorporated into the dynamic model. Age-specific incidence rates and case-fatality ratios for pneumococcal pneumonia, meningitis, AOM and NPNM were drawn from Egyptian economic evaluations [

3,

4] and adjusted to remain consistent with Global Burden of Disease estimates [

1], providing locally relevant disease burden inputs.

Vaccine effectiveness estimates were based on Sibak et al. [

3] and then refined using PCV13 serotype coverage data from Badawy et al. [

20]. To reflect expected post-introduction epidemiology, vaccine effectiveness values for invasive disease were further adjusted for serotype replacement using evidence from Weinberger et al. [

21]. The model also applies a 20% reduction in vaccine-targeted serotype coverage for invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPDs) over the analysis period to account for replacement, ensuring realistic long-term impact estimates.

As natural immunity after infection is serotype-specific and short-lived, serotype prevalence ranges widely and multi-serotype carriage is common. Based on these considerations [

14,

21,

22], natural immunity was conservatively set at 33% of vaccine-induced protection, high enough to account for some cross-protection but low enough to avoid underestimating the incremental value of vaccination. An assumed reproduction number (R₀) of 1.25 was used to reflect pneumococcal transmission dynamics in high-burden settings. This value is consistent with estimates reported in the literature, where pre-vaccine R₀ for

Streptococcus pneumoniae typically ranges from 1.2 to 1.4 depending on serotype distribution, population density and age-mixing patterns [

23].

These inputs ensure that transmission dynamics, vaccine effects and disease outcomes reflect both local epidemiology and established biological mechanisms.

2.4. Cost and Effects

Budget impact and cost-effectiveness was assessed over the 20-year modelling horizon. Only direct healthcare costs were included, defined as the average cost per incident case of each pneumococcal syndrome (

Table 3), alongside vaccine procurement and delivery costs modelled under several price scenarios (

Appendix B). Procurement and delivery costs incorporated standard components used in global immunisation costing, including delivery unit costs, freight and handling fees, injection supplies, surcharge structures, and human resource inputs, drawing on WHO and UNICEF Supply Division methodologies and country-level delivery cost databases [

24,

25,

26,

31], with additional verification from UNICEF SD.

Health effects were measured in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), calculated each cycle as years of life lost plus years lived with disability. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were computed by dividing incremental costs by the DALYs averted relative to the business-as-usual (BAU) scenario. Vaccine procurement costs were set at USD 16.00 per dose for PCV13 and USD 3.45 for PCV10 [

32], resulting in total programme costs of USD 68.00 and USD 20.57 per fully vaccinated child, respectively.

Adverse events following immunization were not modelled in the analysis. This decision was based on the assumption that severe adverse events associated with both PCV10 and PCV13 vaccination are uncommon, in line with the decision made by existing economic evaluations [

33,

34].

2.5. Calibration

The model was calibrated to reproduce a realistic BAU scenario prior to vaccine introduction. To do this, a 21-year burn-in period was used to stabilise infection levels and align the simulated population with Egypt’s demographic structure in the first analysis year. Calibration targets included reported incidence rates for acute otitis media, meningitis, non-pneumonia/non-meningitis invasive disease, and pneumococcal pneumonia. Model parameters were iteratively adjusted until simulated age-specific incidence patterns matched observed BAU values.

Population dynamics were incorporated through a demographic transition matrix that moves individuals into older age groups or death over time, ensuring that age-specific transmission patterns evolve with the underlying population structure.

The model was implemented in R (version 4.2), with Excel used for supplementary tabulation and diagramming.

2.6. Scenario Analysis Reflecting Egyptian Context

To address the question of affordability and sustainable financing, reflecting the Egyptian context, the analysis explored various scenarios based on two key variables, the time of introduction (discussed here) and cost of vaccination (section 2.4). Firstly, the BAU scenario reflects the current situation in Egypt where no S.Pn vaccination occurs. The intervention scenarios vary the time of vaccination introduction from immediate, 5-year delay and 10-year delay. Regarding vaccine products, as PCV13 is the priority vaccine product for Egypt [

7], it was included in all modelled scenarios. To assess the price implications of introducing a lower-cost alternative, we also modelled two scenarios where immediate introduction of UNICEF-procured PCV10 was introduced, followed by either a switch or a gradual transition to domestically produced PCV13. For all scenarios that include UNICEF procurement, Gavi MICs support is incorporated.

2.7. Domestic Manufacturing Cost Assumptions

In addition to the 5 scenarios, the analysis considered varied domestic manufacturing cost assumptions. The analysis used the UNICEF long-term arrangement (LTA) price as a benchmark and explored potential deviations due to local manufacturing. The analysis allowed domestic manufacturing prices to be either higher or lower than the UNICEF LTA price, reflecting insights from both experts and the literature. Some evidence suggests local production could raise costs [

36], while expert opinion highlights potential cost reductions through economies of scale and lower logistics expenses [

37]. UNICEF LTA price was therefore used as a benchmark, and domestic manufacturing prices were estimated at a -10%, 0%, +10% change. For the immediate initiation two additional scenarios were defined. One with the change from PCV10 pricing to PCV13 pricing in year 5, and a second with gradual change of three years of change from PCV10 to PCV13.

Table 4 gives an overview of the scenarios.

2.8. Sensitivity Analysis

To test the robustness of the model and outcomes a one-way sensitivity analysis was performed on the cost of vaccination, vaccination uptake, years of life lost at premature death, vaccination effectiveness on transmission and effectiveness on transmission for natural immunity. In addition, the following parameters were included for every disease, including cost of treatment, disutility, duration, case-fatality rate, vaccine effectiveness and incidence. The key parameters were varied by +/- 20% in order to determine the impact. For parameters that applied to all three age groups, the values were varied simultaneously, generating a single sensitivity analysis outcome. The sensitivity was performed on the immediate vaccination scenario with 0% change on the vaccination cost.

3. Results

Results are first presented for the base-case analysis of immediate PCV13 introduction, followed by comparative scenario and sensitivity analyses. Outcomes are reported as deaths averted, ICERs expressed relative to GDP per capita, annual budget impact, and return on investment over a 20-year time horizon.

3.1. Base-Case Cost-Effectiveness, Budget Impact and ROI

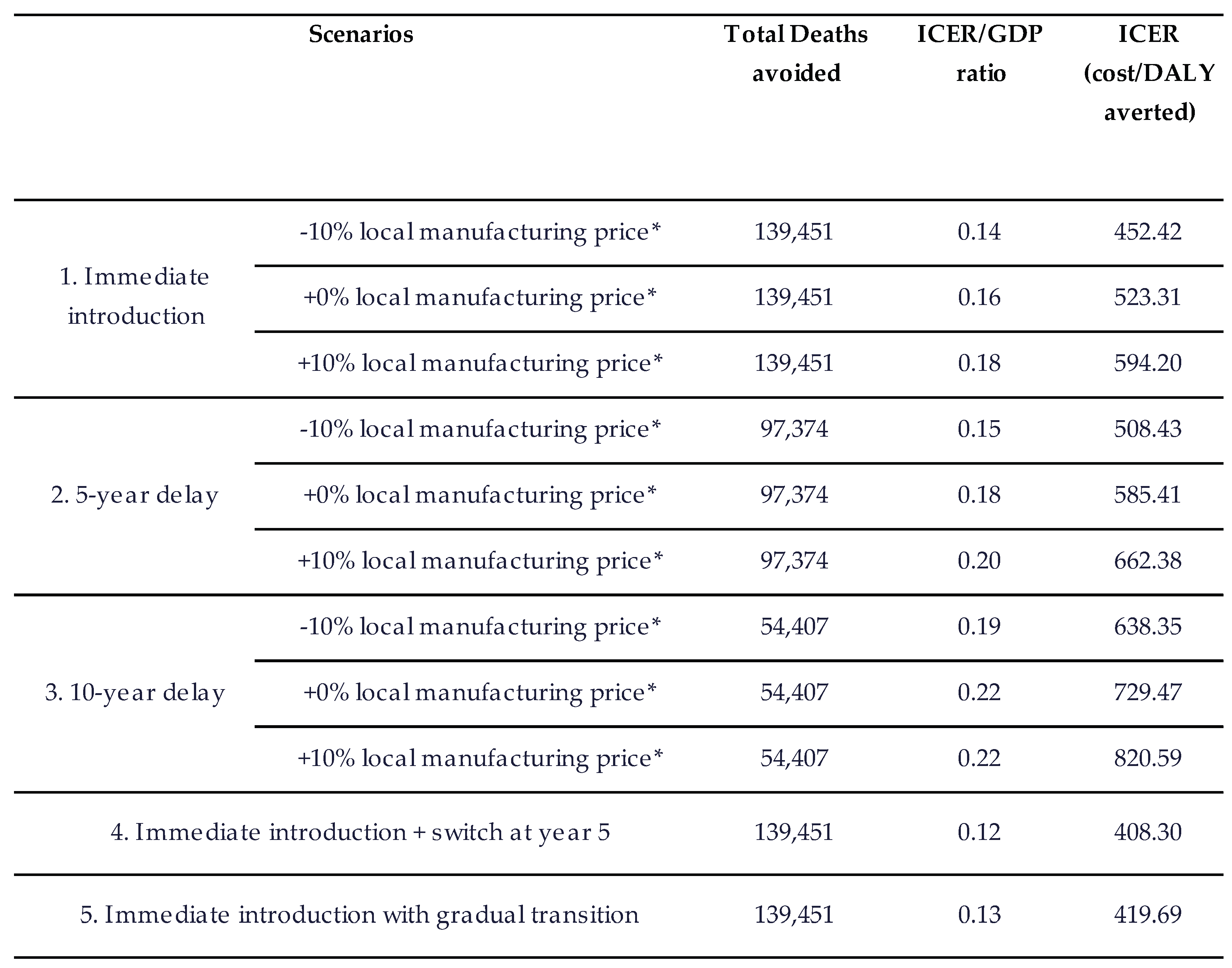

In the base-case scenario of immediate PCV13 introduction at the UNICEF LTA price, vaccination is projected to avert 139,451 deaths over 20 years compared with business as usual (

Table 5). The ICER/GDP ratio of 0.16 indicates that the intervention is highly cost-effective.

The base case results in a total annual budget impact of USD 124.91 million without Gavi support and USD 120.94 million with Gavi support. The programme delivers a return-on-investment of 23.12, reflecting substantial savings from reduced pneumococcal disease burden.

These findings form the benchmark for interpreting all subsequent scenario and sensitivity analyses.

Across all scenarios, earlier introduction of pneumococcal vaccination produced greater health impact than delayed implementation (

Table 6). Relative to the base case, a 5-year delay reduces deaths avoided from 139,451 to 97,374 (42,077 fewer deaths; 30.2% reduction). A 10-year delay further reduces deaths avoided to 54,407 (85,044 fewer deaths; 61.0% reduction) over 20 years.

Variation in domestic manufacturing price assumptions leads to modest increases in ICER/GDP ratios; however, all scenarios remain highly cost-effective. Differences are driven primarily by changes in program cost, as health outcomes remain comparable across price levels (

Table 6).

Alternative product pathways also perform favorably relative to the base case. Scenarios involving immediate PCV10 introduction followed by PCV13—via a direct switch in year 5 or a gradual transition, result in ICER/GDP ratios of 0.12 and 0.13, respectively, reflecting lower initial vaccination costs while achieving similar long-term health outcomes. Overall, the scenario results indicate that delaying PCV introduction substantially diminishes both health and economic benefits, while immediate introduction whether with PCV13 or a temporary PCV10 pathway provides the highest value.

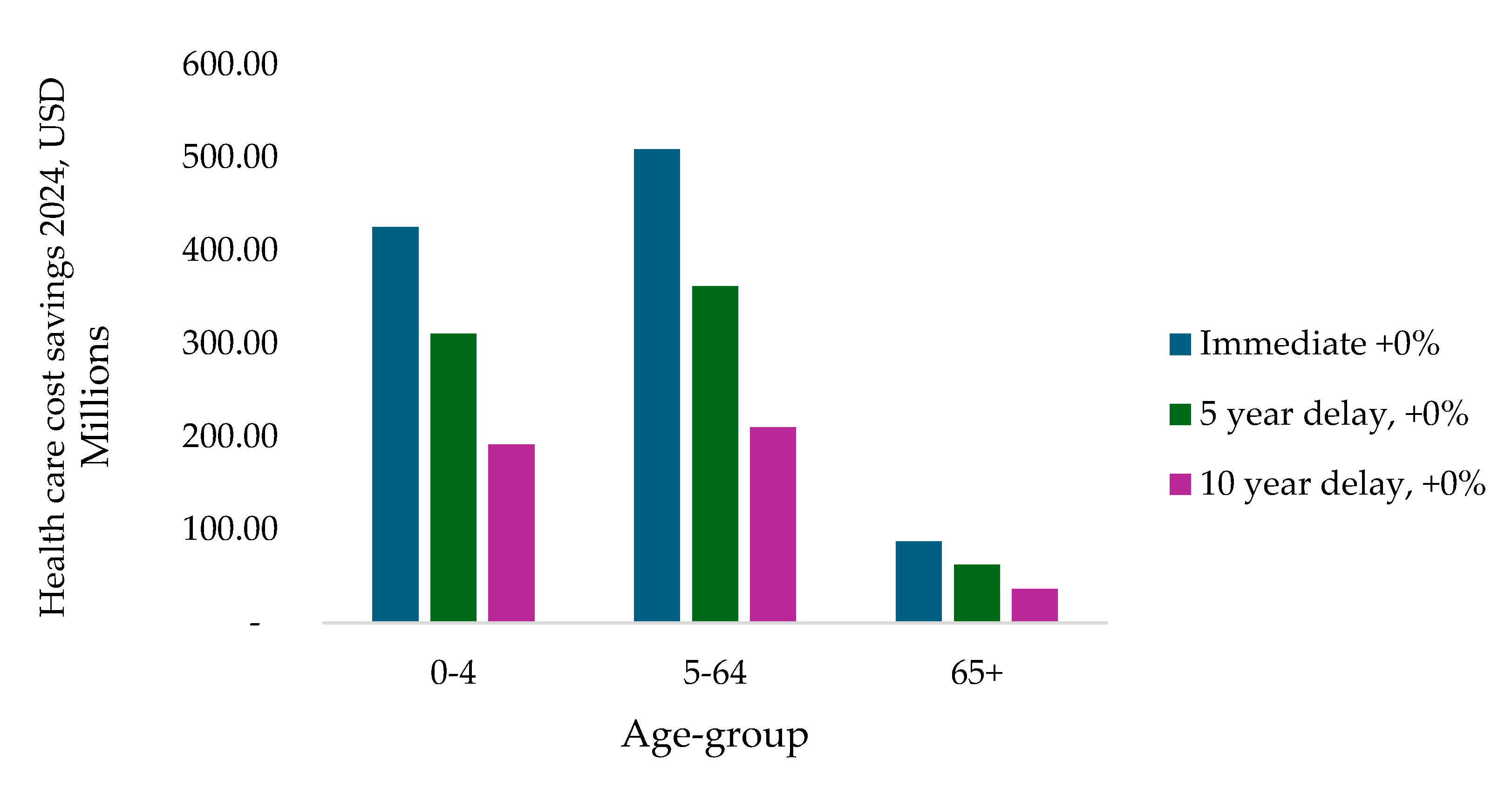

3.2. Age-Specific Distribution of Healthcare Cost Savings

Figure 2 presents the distribution of healthcare cost savings by age group across the immediate introduction, 5-year delay, and 10-year delay scenarios using the base PCV13 price. Immediate introduction produces the largest cost savings in all age groups. The greatest reductions occur in the 0–4 and 5–64 age groups, reflecting their higher burden of pneumococcal disease. Savings in the 65+ age group are smaller in absolute terms but remain positive across all scenarios. Overall, a substantial share of total healthcare cost savings occurs among individuals aged over five years.

3.3. Budget Impact

Table 7 presents the annual average budget impact of pneumococcal vaccination across all scenarios, with and without Gavi support, as well as the corresponding return-on-investment (ROI) over the 20-year horizon. Immediate introduction of PCV13 results in the highest budget expenditure but also the greatest long-term savings, reflected in the highest ROI among the PCV13 scenarios.

Delaying introduction reduces the overall budget impact; however, these scenarios are associated with lower ROI values compared with the base case. Alternative product pathways show favorable performance, with immediate PCV10 introduction followed by a switch to PCV13 yielding the highest ROI and the lowest budget impact within the immediate-introduction scenarios.

3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

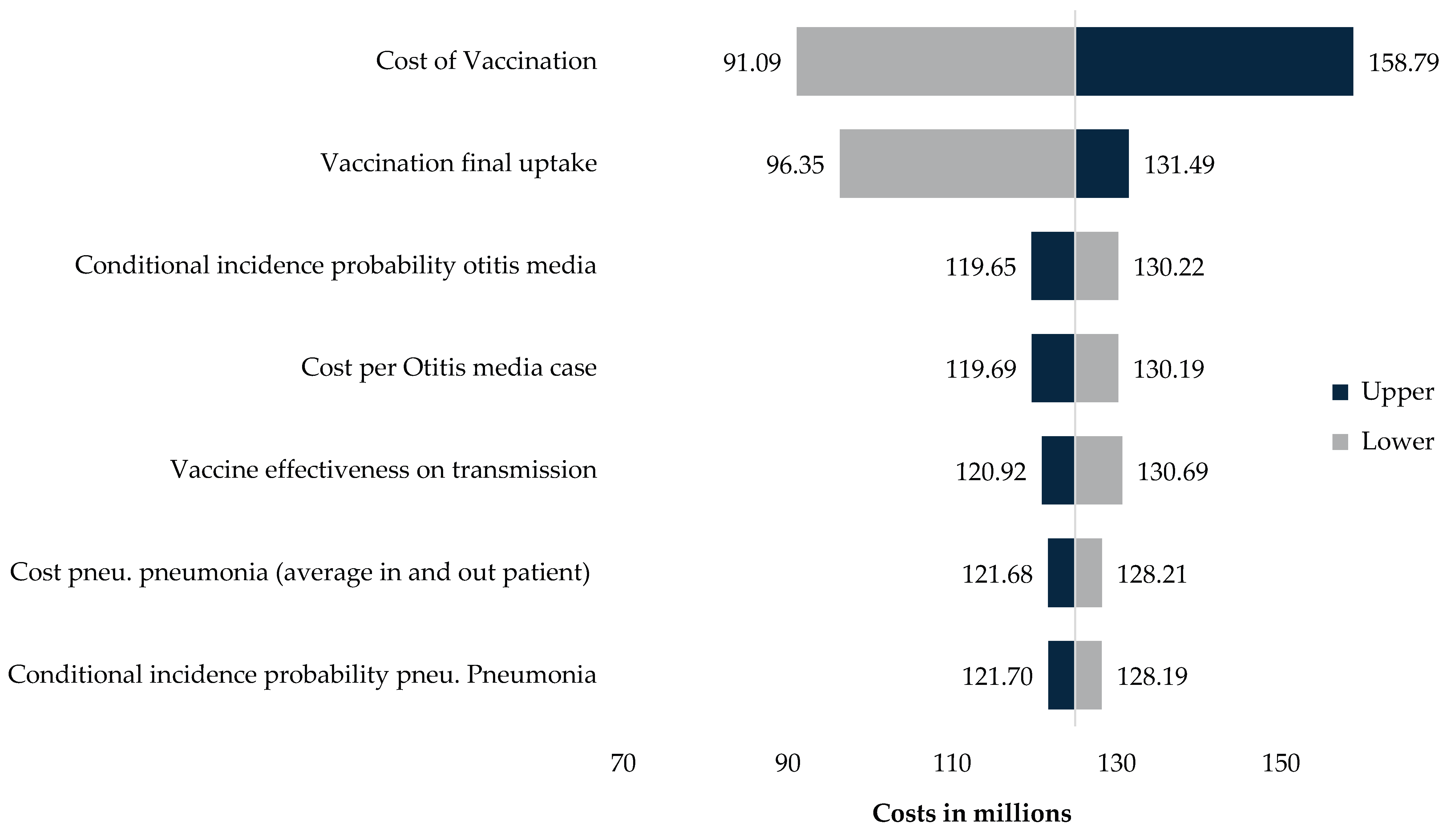

One-way sensitivity analysis (

Appendix C) shows that vaccine price and vaccination uptake are the are the two parameters with the greatest influence on cost-effectiveness and budget impact outcomes. A ±20% change in vaccine price results in annual average costs ranging from approximately USD 91 million to USD 159 million, compared with around USD 125 million in the base case. A ±20% change in vaccination uptake produces annual budget impacts between approximately USD 96 million and USD 131 million.

Other parameters, including disease-specific incidence, case-fatality rates, and disutility values, produced comparatively smaller changes in outcomes. Overall, the sensitivity analysis shows that model results are most responsive to changes in program cost and uptake levels.

As an internal validation step, we modelled a direct-effects-only scenario (excluding herd protection). This reduced total deaths averted to approximately 46,000 over 20 years (≈2,300 per year), with corresponding ICERs of 0.27–0.38× GDP per capita and an ROI of USD 6–8 per dollar invested (

Appendix C).

4. Discussion

This dynamic, age-structured cost-effectiveness analysis shows that introducing PCVs into Egypt’s routine immunization schedule is highly cost-effective and yields substantial health and economic benefits. Across all implementation scenarios, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were well below commonly used willingness-to-pay thresholds, and the ROI ranged from roughly US$16 to US$28 per dollar spent. Immediate introduction of PCV13 was projected to avert about 139 451 deaths over twenty years, or nearly 6 972 deaths per year, and to generate significant savings in health-care expenditure through reductions in pneumonia, meningitis, non-pneumonia non-meningitis invasive disease and acute otitis media (AOM).

Earlier Egyptian economic evaluations of PCVs have produced more conservative estimates of health gains and higher cost-effectiveness ratios. Sibak et al. [

3] evaluated PCV13 using a static model that restricted benefits to children under five years and estimated roughly 800–2,500 deaths averted per year, with ICERs between 0.26 and 1.2 times Egypt’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita [

3]. Sevilla et al. employed a pseudo-dynamic Markov model over a 100-year horizon and reported about 2,300 deaths averted per year with ICERs near one times GDP per capita [

4]. A global pseudodynamic analysis across 112 LMICs by Chen et al. suggested that PCV13 introduction could avert approximately 697,000 deaths and 46 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally, with an incremental cost of 851 International dollars per DALY averted; scaled to Egypt, this implies 1,000–1,800 preventable under-five deaths per year [

6]. Other LMIC analyses that account for indirect protection report cost-effectiveness ratios of about 0.20 × GDP per capita and above [

38,

39,

40]. The direct-effects-only sensitivity analysis further supports the validity of the model. Under this scenario, the model projects ~46,000 deaths averted over 20 years (≈2,300 annually) with ICERs of 0.27–0.38× GDP per capita, more closely matching estimates from earlier Egypt-specific evaluations and global LMIC analyses of under-five mortality [

3,

4,

6]. This concordance indicates that the higher mortality reductions observed in the full dynamic model arise from the inclusion of older age groups and indirect protection rather than from overly optimistic assumptions. Compared with these studies, our model predicts substantially greater health gains and more favorable cost-effectiveness.

Several methodological features help explain why this dynamic model produces larger estimated health and economic benefits than earlier Egyptian evaluations [

3,

4]. Unlike previous studies that focused primarily on children under five or used static herd-immunity-effect assumptions, our model applies the nationally adjusted disease burden across all age groups and explicitly simulates transmission, capturing substantial indirect protection in older children and adults. The 20-year horizon concentrates outcomes within a policy-relevant timeframe, whereas longer horizons dilute annualized effects. Inclusion of acute otitis media and outpatient pneumonia, major contributors to morbidity and cost [

41], also increases overall gains compared with models limited to invasive disease. We additionally assume more conservative natural immunity (one-third of vaccine-derived protection), which increases the incremental benefit of vaccination [

14,

21,

22]. Finally, updated 2024 cost data and inclusion of the value of prevented premature deaths yield higher return-on-investment estimates than earlier analyses based mainly on direct medical costs.

4.1. Policy Implications and Optimal Introduction Strategy

The base case of immediate PCV13 introduction using UNICEF long-term agreement pricing produces the largest health gains and strongest economic returns. Delaying introduction by five or ten years reduces deaths averted by approximately 30% and 61%, respectively, and lowers ROI, even though delayed scenarios require lower annual budgets in absolute terms. Variation in domestic manufacturing prices has only a modest effect on ICERs; however, lower local prices improve ROI. Scenarios that begin with PCV10 procurement through UNICEF and then transition to locally manufactured PCV13 achieve health benefits comparable to immediate PCV13 introduction and yield the highest ROIs and the lowest annual budget requirements. These findings suggest that a dual-track approach, early adoption through international procurement, followed by a gradual shift to domestic production, can balance immediate health gains with long-term fiscal sustainability and industrial policy objectives.

PCV10 is only slightly less effective against currently prevalent serotypes but may offer lower long-term protection because of serotype replacement [

42]. Its price, however, is roughly 80% lower than PCV13 [

32], making it an attractive alternative when budget constraints preclude immediate PCV13 adoption. In such circumstances, implementing PCV10 first and transitioning to PCV13 once local manufacturing is established can still deliver strong health benefits and economic value.

Our pricing assumptions were intended to capture higher unit costs during the early phases of domestic production and lower costs once manufacturing reaches scale and enables regional export, operationalized as ±10% relative to the UNICEF long-term agreement price. This approach is supported by evidence showing that domestically manufactured vaccines are often more expensive per dose in their early years than vaccines procured through Gavi or UNICEF pooled mechanisms [

43,

44]. This pattern has been observed for PCVs and other vaccines, reflecting high upfront R&D and technology-transfer costs, limited initial production scale, and restricted early market access [

43,

45]. In South Africa, local fill-and-finish production of PCV13 was reported to be more expensive than an imported alternative, leading to a subsequent switch [

45]. While realized prices will depend on country-specific production arrangements and scale, these scenarios reflect a plausible, evidence-informed range rather than precise price forecasts.

The annual average budget impact of PCV as a proportion of the latest available annual healthcare expenditure for Egypt (2022), is 0.46–0.47% [

5]. For comparison, the latest vaccine expenditure data (2022) suggests Morocco and Tunisia spend 0.07% and 0.24% of annual healthcare expenditure respectively, on all vaccines combined [

46]. Compared to international benchmarks, the budget impact for all PCV scenarios in Egypt falls within the spending range for vaccine investments which typically account for 0.4–1.4% of total health expenditure [

47,

48,

49,

50].

4.2. Limitations and Generalizability

This analysis has some limitations. Estimates of incidence and case fatality were derived from older published Egyptian and regional sources rather than comprehensive up to date Egyptian surveillance data, and may therefore reflect measurement uncertainty. Assumptions regarding natural immunity, serotype replacement, and the duration of vaccine-derived protection may also differ from real-world dynamics. Indirect societal costs were not included, suggesting that the cost-effectiveness of PCV introduction may be conservative. Although the dynamic model captures herd immunity effects within Egypt, generalizability to other settings will depend on local epidemiology, coverage levels, and cost structures. The model also did not incorporate a one-time catch-up campaign recommended by SAGE [

17], though its exclusion is unlikely to materially affect 20-year results. Finally, the use of three age groups and the assumption of comparable effectiveness for PCV10 and PCV13 reflect modelling constraints and introduce additional uncertainty, although WHO considers both vaccines highly immunogenic.

5. Conclusions

This dynamic evaluation confirms that PCV introduction in Egypt represents a high-value investment. By including all age groups, adopting a decision-relevant time horizon, incorporating outpatient disease, using realistic natural immunity assumptions, modelling herd immunity effects and serotype replacement, and applying updated economic valuation, the model estimates far larger health and economic gains than earlier under-five-only analyses. Immediate introduction maximizes benefits; delays come with substantial opportunity costs in preventable deaths and health-care savings. Combining early PCV10 adoption with a timely transition to PCV13 can preserve strong health impact while supporting domestic manufacturing goals and maintaining fiscal sustainability.

Author Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work - Chrissy Bishop, Arnold Hagens, Federico Carioli, Zicheng Wang, Konstantina Politopoulou, Saadia Farrukh, Motuma Abeshu, Sowmya Kadandale, Ibironke Oyatoye. Methodology, Arnold Hagens, Chrissy Bishop. Validation, Federico Cairoli, Saadia Farrukh, Motuma Abeshu, Sowmya Kadandale, Ibironke Oyatoye. Formal analysis – Arnold Hagens and Chrissy Bishop. Investigation – Arnold Hagens, Federico Cairoli and Chrissy Bishop. Data curation – Arnold Hagens, Chrissy Bishop, Federico Cairoli, Zicheng Wang and Konstantina Politopoulou; Writing—original draft preparation, Chrissy Bishop, Arnold Hagens. Writing and drafting of the work or revising critically for important intellectual content - Chrissy Bishop, Arnold Hagens, Federico Cairoli, Saadia Farrukh, Motuma Abeshu, Sowmya Kadandale, Ibironke Oyatoye. Visualization – Arnold Hagens; Final approval of version to be published - Chrissy Bishop, Arnold Hagens, Federico Cairoli, Zicheng Wang, Konstantina Politopoulou, Saadia Farrukh, Motuma Abeshu, Sowmya Kadandale, Ibironke Oyatoye.

Funding

UNICEF Regional Office for Middle East and North Africa undertook this work in collaboration with Triangulate Health Ltd through the gracious financial support from Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request to the author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Maureen Gallagher, Dr. Essam Allam, and Dr. Mutribjon Bahruddinov from the UNICEF Egypt Country Office, as well as Ms. Caitlin Longden from Gavi, the vaccine Alliance for their valuable contributions to the situational analysis and for providing general technical support throughout the development of this study. We also thank the Egyptian Ministry of Health for its collaboration and policy-relevant guidance. The authors have reviewed and edited the manuscript and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DALYs |

Disability-adjusted life years |

| ICER |

Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product |

| Gavi |

Gavi the Vaccine Alliance |

| IPD |

Invasive pneumococcal disease |

| LMICs |

Low-and middle-income countries |

| LTA |

Long-term arrangement |

| PCV10 |

10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

| PCV13 |

13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

| ROI |

Return on Investment |

| S.Pn |

Streptococcus Pneumoniae |

| WTP |

Willingness to pay |

Appendix A. Dynamic Transition Model

Table A1.

Dynamic transition model equations.

Table A1.

Dynamic transition model equations.

For each age group

i, the rate of change in the number of infectious individuals is defined by equations 1, 2 and 3. These equations allow the model to capture how vaccination alters susceptibility, transmission and progression across the population, and how indirect protection evolves over time.

where:

Appendix B. Cost per Child Vaccinated

Table A2.

Cost per child vaccinated using UNICEF LTA prices, 2024 USD.

Table A2.

Cost per child vaccinated using UNICEF LTA prices, 2024 USD.

| Product |

Cost of vaccine |

Handling |

Injection supply |

Buffer applied to product price (6%) |

Total vaccination cost per child, USD (3 doses) |

| PCV price, USD (3 doses) |

Wastage 17% (cost, USD) |

Delivery (cost, USD) |

Vaccines 3.5% |

Freight 3.2% |

Injection supply, 3 doses (cost, USD) |

Wastage 10% (cost, USD) |

Handling AD syringes, 16% |

Freight fees (20%) |

Surcharge (8%) |

| PCV13 |

48.00 |

8.16 |

7.02 |

1.68 |

0.22 |

0.16 |

0.016 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.0026 |

2.88 |

68.20 |

| PCV10 |

10.35 |

1.76 |

7.02 |

0.36 |

0.22 |

0.16 |

0.016 |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.0026 |

0.62 |

20.57 |

Appendix C. Sensitivity Analyses

Figure A1.

Tornado diagram.

Figure A1.

Tornado diagram.

Table A3.

Key results of budget-impact analysis, cost-effectiveness, and return on investment for each scenario, focusing exclusively on the health benefits for children under 5 years old.

Table A3.

Key results of budget-impact analysis, cost-effectiveness, and return on investment for each scenario, focusing exclusively on the health benefits for children under 5 years old.

| Scenarios |

Total Deaths avoided |

ICER/GDP ratio |

Disability adjusted life years (DALYs) averted. |

Total budget Impact without Gavi (Annual avg) |

Total budget Impact with Gavi (Annual avg) |

Return-on investment |

| Immediate |

-10% local manufacturing price |

46,047 |

0.27 |

2,160,398 |

133.60 |

130.02 |

7.8 |

| +0% local manufacturing price |

46,047 |

0.30 |

2,160,398 |

150.52 |

146.55 |

6.9 |

| +10% local manufacturing price |

46,047 |

0.33 |

2,160,398 |

167.44 |

163.08 |

6.2 |

| 5-year delay |

-10% local manufacturing price |

32,847 |

0.29 |

1,419,346 |

99.94 |

96.58 |

7.2 |

| +0% local manufacturing price |

32,847 |

0.33 |

1,419,346 |

113.25 |

109.49 |

6.3 |

| +10% local manufacturing price |

32,847 |

0.36 |

1,419,346 |

125.87 |

121.74 |

5.7 |

| 10-year delay |

-10% local manufacturing price |

19,188 |

0.34 |

767,431 |

66.19 |

63.06 |

6.1 |

| +0% local manufacturing price |

19,188 |

0.38 |

767,431 |

74.84 |

71.34 |

5.3 |

| +10% local manufacturing price |

19,188 |

0.38 |

767,431 |

75.33 |

71.80 |

4.8 |

| Immediate, switching price from PCV10 to PCV13 in year 5, +10% local manufacturing price |

46,047 |

0.25 |

2,160,398 |

130.15 |

129.45 |

8.4 |

| Immediate, gradually switching from PCV10 to PCV13 (years 4-7) +10% local manufacturing price |

46,047 |

0.25 |

2,160,398 |

132.12 |

130.86 |

8.2 |

References

- IHME. Institute For Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Data Resources | GHDx. 2019. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019.

- Farrar, J.L.; Childs, L.; Ouattara, M.; Akhter, F.; Britton, A.; Pilishvili, T.; Kobayashi, M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy and Effectiveness of Pneumococcal Vaccines in Adults. Pathogens 2023, Vol 12, [Internet]. 18 May 2023, 12. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/12/5/732.

- Sibak, M.; Moussa, I.; El-Tantawy, N.; Badr, S.; Chaudhri, I.; Allam, E.; Baxter, L.; Abo Freikha, S.; Hoestlandt, C.; Lara, C.; et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) in the Egyptian national immunization program, 2013. Vaccine [Internet] 2015, 33 Suppl 1(S1), A182–91. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25919159/. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevilla, JP; Burnes, D; El Saie, RZ; Haridy, H; Wasserman, M; Pugh, S; et al. Cost-utility and cost-benefit analysis of pediatric PCV programs in Egypt. In Hum Vaccin Immunother [Internet]; 2022; 18, 6. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36070504/.

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data | Data [Internet]. 18 Sep 2024. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/.

- Chen, C; Ang, G; Akksilp, K; Koh, J; Scott, JAG; Clark, A; et al. Re-evaluating the impact and cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine introduction in 112 low-income and middle-income countries in children younger than 5 years: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2024, 12(9), e1485–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egyptian Vaccine Manufacturers Alliance (EVMA). EGYPT NATIONAL STRATEGY FOR VACCINE MANUFACTURING LOCALIZATION [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://evma-egypt.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Strategy-Combined-.pdf.

- Gavi. Gavi’s approach to engagement with middle-income countries. 2022.

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). Establishing Manufacturing Capabilities for Human Vaccines Key cost drivers and factors to consider when planning the establishment of a vaccine production facility [Internet]. 2017. Available online: www.unido.org.

- Chadwick, C; Friede, M; Moen, A; Nannei, C.; Sparrow, E. Technology transfer programme for influenza vaccines – Lessons from the past to inform the future. Vaccine [Internet] 2022 Aug 5 [cited 2025 Nov 24], 40(33), 4673. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9406834/. [CrossRef]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Augustovski, F.; de Bekker-Grob, E.; Briggs, A.H.; Carswell, C.; Caulley, L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N.; Greenberg, D.; Loder, E.; et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. BMC Med [Internet] 2022, 20(1), 1–8. Available online: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-021-02204-0.

- Vynnycky, E.; White, R. An Introduction to Infectious Disease Modelling.

- Weiser, JN; Ferreira, DM; Paton, JC. Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018 Mar 29 [cited 2025 Dec 15], 2018 16 16(6), 355–67. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-018-0001-8. [CrossRef]

- van Zandvoort, K; Hassan, AI; Bobe, MO; Pell, CL; Ahmed, MS; Ortika, BD; et al. Pre-vaccination carriage prevalence of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes among internally displaced people in Somaliland: a cross-sectional study. Pneumonia 2024 Dec 5 [cited 2025 Dec 15, 2024 16:1 16(1), 25. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s41479-024-00148-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prem, K.; Cook, AR; Jit, M. Projecting social contact matrices in 152 countries using contact surveys and demographic data. PLoS Comput Biol [Internet] 2017 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Nov 13], 13(9), e1005697. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005697. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) [Internet]. 2019. Available online: https://terrance.who.int/mediacentre/data/sage/SAGE_Docs_Ppt_Oct2019/0_SAGE_Yellow_Book_October_2019.pdf.

- WHO. Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) - SAGE Working Group on Pneumococcal Vaccines [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/strategic-advisory-group-of-experts-on-immunization/working-groups/pneumococcal-vaccines.

- Elsisi, G.H.; Kaló, Z.; Eldessouki, R.; Elmahdawy, M.D.; Saad, A.; Ragab, S.; Elshalakani, A.M.; Abaza, S. Recommendations for Reporting Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations in Egypt. Value Health Reg Issues 2013, 2(2), 319–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichon-Riviere, A; Drummond, M; Palacios, A; Garcia-Marti, S; Augustovski, F. Determining the efficiency path to universal health coverage: cost-effectiveness thresholds for 174 countries based on growth in life expectancy and health expenditures. Lancet Glob Health [Internet] 2023 Jun 1 [cited 2024 Jun 11], 11(6), e833–42. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S2214109X23001626/fulltext. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badawy, M.; ElKholy, A.; Sherif, M.M.; Rahman, E.A.; Ashour, E.; Sherif, H.; Mahmoud, H.E.; Hamdy, M. Serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Egyptian children: are they covered by pneumococcal conjugate vaccines? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis [Internet]. 2017, 36(12), 2385–9. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28744663/. [PubMed]

- Weinberger, D.M.; Warren, J.L.; Dalby, T.; Shapiro, E.D.; Valentiner-Branth, P.; Slotved, H.-C.; Harboe, Z.B. Differences in the Impact of Pneumococcal Serotype Replacement in Individuals With and Without Underlying Medical Conditions. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2019 Jul 7 [cited 2024 Sep 18, 69(1), 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nawawy, AA; Hafez, SF; Meheissen, MA; Shahtout, NMA; Mohammed, EE. Nasopharyngeal Carriage, Capsular and Molecular Serotyping and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Streptococcus pneumoniae among Asymptomatic Healthy Children in Egypt. J Trop Pediatr [Internet] Available from. 2015 Dec 1 [cited 2025 Dec 15], 61(6), 455–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoti, F; Erästö, P; Leino, T; Auranen, K. Outbreaks of Streptococcus pneumoniaecarriage in day care cohorts in Finland – implications for elimination of transmission. BMC Infectious Diseases 2009 Jun 27 [cited 2025 Nov 24, 2009 9 9(1), 1 102. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2334-9-102. [CrossRef]

- IMMUNIZATION ECONOMICS. Standardized country-level immunization delivery unit cost estimates. Available at: StandardizedDeliveryUnitCosts4Dec2020-5.xlsx Standardized country-level immunization delivery unit cost estimates. 2020. Available online: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fimmunizationeconomics.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F10%2FStandardizedDeliveryUnitCosts4Dec2020-5.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK.

- UNICEF; UNICEF. Pricing data | UNICEF Supply Division. 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/supply/pricing-data.

- WHO. Vaccine Wastage Rates Calculator [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/vaccine-wastage-rates-calculator.

- Costs of Fully Vaccinating a Child Countries Eligible for Gavi Vaccine Prices. 2024.

- McCabe, C; Paulden, M; Awotwe, I; Sutton, A.; Hall, P. One-Way Sensitivity Analysis for Probabilistic Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Conditional Expected Incremental Net Benefit. Pharmacoeconomics 2020, 38(2), 135–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, A; Abe, M; Weaver, J; Huang, M. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pediatric immunization program with 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Japan. J Med Econ [Internet] 2023, 26(1), 1034–46. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13696998.2023.2245291. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Garcia, C.; Wu, D.; Deloria Knoll, M.; Zhang, H.; Xu, T.; Jing, R.; Yin, Z.; Wahl, B.; Fang, H. Estimating national, regional and provincial cost-effectiveness of introducing childhood 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in China: a modelling analysis. Lancet Reg Health West Pac [Internet]. 1 Mar 2023, p. 32. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S2666606522002814/fulltext.

- UNICEF. Vaccine pricing data. 2024. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/supply/vaccines-pricing-data.

- UNICEF. PCV Vaccine Prices [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/supply/media/23001/file/PCV-vaccine-prices-31012025.pdf.

- Kim, SY; Lee, G.; Goldie, SJ. Economic evaluation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in The Gambia. BMC Infectious Diseases 2010, 2010 10 10(1), 260. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2334-10-260. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwood, M; Beausoleil, L; Breton, MC; Laferriere, C.; Sato, R.; Weycker, D. Cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies for use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) in Canadian adults. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2018 May 9 [cited 2026 Jan 19, 2018 109:5 109(5), 756–68. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.17269/s41997-018-0050-9. [CrossRef]

- Pugh, SJ; Fletcher, MA; Charos, A; Imekraz, L; Wasserman, M.; Farkouh, R. Cost-Effectiveness of the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (10- or 13-Valent) Versus No Vaccination for a National Immunization Program in Tunisia or Algeria. Infect Dis Ther [Internet] 2019, 8(1), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellcome. Scaling Up African Vaccine Manufacturing Capacity: Perspectives from the African vaccine-manufacturing industry on the challenges and the need for support. 2023. Available online: https://cms.wellcome.org/sites/default/files/2023-01/Wellcome-Biovac-BCG-Scaling-up-African-vaccine-manufacturing-capacity-report-2023_0.pdf.

- Triangulate Health Ltd. Interview with Gavi focal point. 2025.

- Dorji, K.; Phuntsho, S.; Pempa; Kumluang, S.; Khuntha, S.; Kulpeng, W.; Rajbhandari, S.; Teerawattananon, Y. Towards the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in Bhutan: A cost-utility analysis to determine the optimal policy option. Vaccine 2018, 36(13), 1757–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K; Wasserman, M; Liu, D; Yang, YH; Yang, J; Guzauskas, GF; et al. Estimating the cost-effectiveness of an infant 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine national immunization program in China. PLoS One 2018, 13(7), e0201245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cervero Liceras, F.; Flasche, S.; Sidharta, S.; Yoong, J.; Sundaram, N.; Jit, M. Effect and cost-effectiveness of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination: a global modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health [Internet] 2019 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Jun 5, 7(1), e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, NX; Pham, HL; Bui, UM; Ho, HT; Bui, TT. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Pneumococcal Vaccines in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12(19), 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Considerations for Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) Product Choice [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/ee6b3c21-9853-4b51-b81f-d4945e2b2982/content.

- UNICEF. Manufacturing immunisation supplies locally - Q&A series, Discussion with Egypt and South Africa [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.technet-21.org/media/com_groupresources/uploads/468/10.%20QnA%20Series_Local%20Vaccine%20Manufacturing_13-05-2025.pdf#:~:text=%E2%80%A2%20Many%20of%20Biovac%E2%80%99s%20agreements,scale%2C%20and%20become%20more%20competitive.

- AVAC. Local Vaccine Production: Harnessing Its Potential for Equity [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://avac.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/LabToJab-LocalVaxProduction-Nov2023.pdf?utm.

- Cullinan, K. Health Policy Watch Despite Hosting MRNA Hub, South Africa Buys Vaccines From India – Highlighting Tension Between Price Pressures And Local Production -. 2023. Available online: https://healthpolicy-watch.news/despite-hosting-mrna-hub-south-africa-buys-vaccines-from-india-highlighting-tension-between-price-and-local-production/.

- Immunization data - UNICEF DATA [Internet]. 6 Jun 2024. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/dataset/immunization/.

- Kaddar, M; Saxenian, H; Senouci, K; Mohsni, E; Sadr-Azodi, N. Vaccine procurement in the Middle East and North Africa region: Challenges and ways of improving program efficiency and fiscal space. Vaccine 2019, 37(27), 3520–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/vaccine-access/planning-and-financing/immunization-financing-indicators.

- Tunnicliffe, E; Hayes, H; O’neill, P; Chin, S; Brassel, YS; Steuten, L. A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS: Analysing Global Immunisation Expenditure. 6 Nov 2025. Available online: https://www.ohe.org/publications/analysing-global-immunisation-expenditure.

- Onishchenko, K; Hill, S; Wasserman, M; Jones, C; Moffatt, M; Ruff, L; et al. Trends in vaccine investment in middle income countries. Hum Vaccin Immunother [Internet] 2019 Oct 3 [cited 2025 Nov 6], 15(10), 2378. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6816376/. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |