1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of satellite remote sensing technologies, methods for estimating river discharge have become increasingly diverse. Over the past decades, remote sensing has been extensively applied to hydrological monitoring in data-scarce or ungauged regions, significantly advancing river discharge estimation techniques [

1,

2,

3]. Numerous studies by scholars both domestically and internationally have explored the inversion of river discharge using satellite remote sensing and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) data. In satellite-based approaches, Rao et al. [

4] used multi-station hydraulic geometry principles and genetic algorithms to estimate discharge in four major Indian rivers solely from river width time-series data derived from Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) satellites and Landsat imagery, achieving high consistency with in situ measurements. Similarly, Mengen et al. [

5] proposed an automated discharge estimation workflow using Sentinel-1 time-series data, grounded in multi-station hydraulic geometry concepts. For low-altitude remote sensing, Zhao et al. [

6] developed a non-contact, efficient discharge inversion method applicable to multi-scale rivers based on UAV imagery. Yang et al. [

7] utilized high-resolution digital orthophoto maps (DOM) and digital surface models (DSM) from UAVs to validate the feasibility of integrating remote sensing data with the Manning formula for runoff estimation.

Accurate extraction of river water bodies forms the foundation of discharge estimation. Existing remote sensing methods for water body identification are primarily categorized into supervised and unsupervised classification [

8,

9]. Supervised techniques rely on image recognition algorithms such as neural networks [

13] and support vector machines [

14,

15] for water extraction [

10,

11,

12]. Among unsupervised methods, single-threshold approaches are prevalent, with the Otsu method (maximum inter-class variance) widely adopted for image segmentation due to its clear principles and high stability [

16,

17,

18,

19]. In synthetic aperture radar (SAR) image processing, where spectral differences between water bodies and background pixels are pronounced, Otsu is frequently used to rapidly determine segmentation thresholds and separate target classes [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Spectral index methods also play a key role in water extraction. McFeeters [

25] introduced the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in 1996, which enhances reflectance differences between green and near-infrared bands to highlight water features. However, NDWI exhibits limitations in distinguishing urban built-up areas from water bodies [

26]. To address this, Xu [

27,

28] proposed the Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) in 2006, substituting the near-infrared band with the mid-infrared band to amplify spectral contrasts between water and built-up land, thereby effectively suppressing background noise.

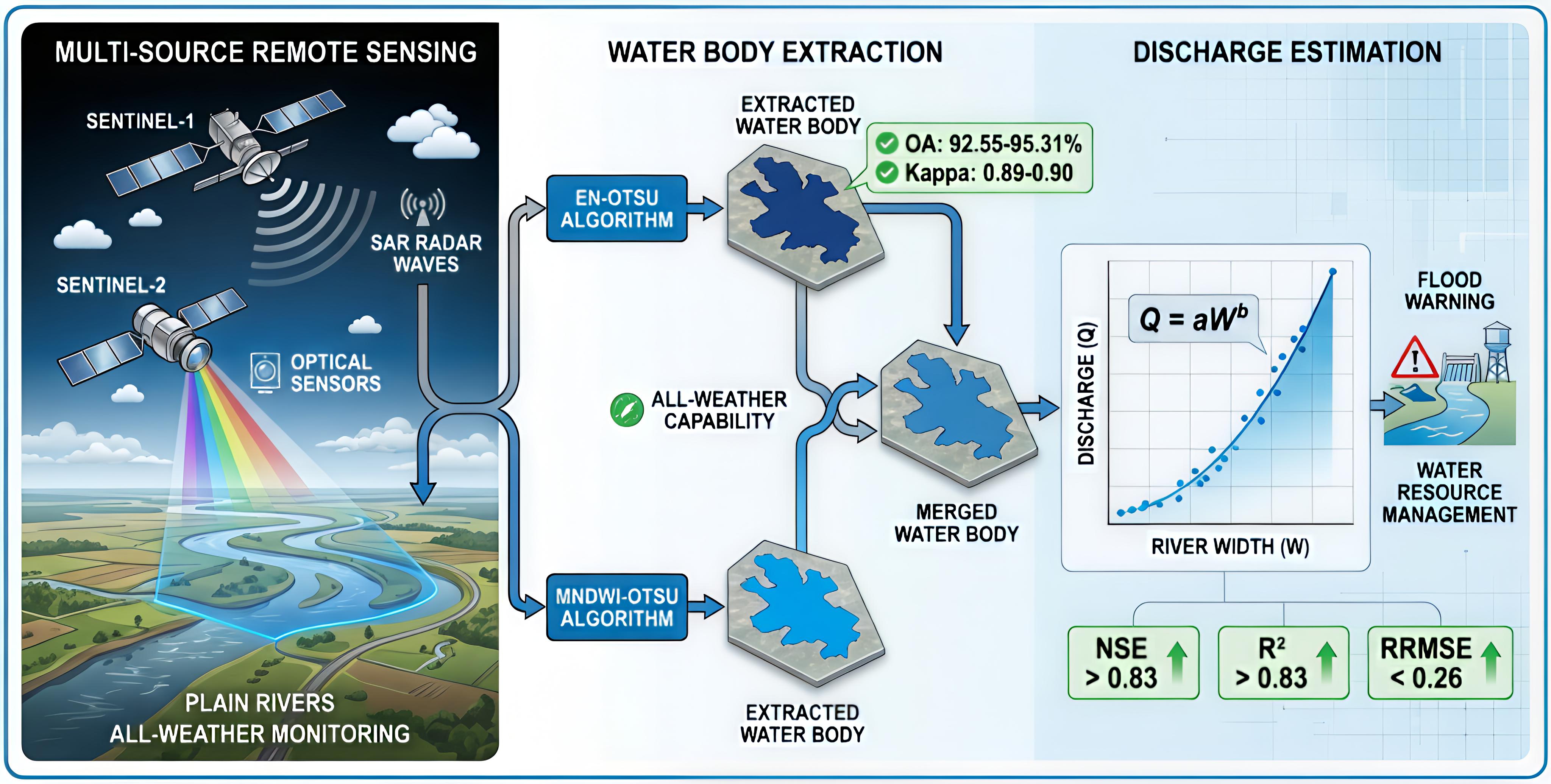

In summary, remote sensing not only enables the acquisition of critical basin hydrological variables such as river width, water level, and surface velocity but also offers unique advantages in macro-scale, real-time, and continuous monitoring. This is particularly valuable in regions lacking in situ observations, where it compensates for data gaps and provides reliable support for river discharge estimation. Building on these advancements, this study targets the Fuyang River LHK hydrological station in Handan City, Hebei Province, China, leveraging Sentinel-1 SAR and Sentinel-2 optical imagery to investigate multi-source remote sensing-based river water body extraction and synergistic discharge estimation. By comparatively analyzing the extraction accuracies of algorithms such as EN-OTSU and MNDWI-OTSU across data sources, we construct a river width calculation model using the water area-to-length ratio approach and a power-function discharge estimation model based on river width. This study hypothesizes that fusing multi-source data will reduce errors by at least 10% compared with single-sensor methods, exploring the complementary mechanisms of multi-source data in monitoring small- to medium-sized rivers, validating the applicability of non-contact remote sensing in complex environments, and offering essential technical support for dynamic river monitoring, flood-drought disaster early warning, and informed water resource management in data-scarce areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The construction and accuracy validation of remote sensing-based discharge inversion models are highly dependent on the morphological characteristics of the river channel and the surrounding terrestrial environment in the study area. Although remote sensing offers advantages in basin-wide monitoring, complex mountainous terrains with fragmented topography and dense vegetation often introduce substantial errors in water body extraction due to shadowing effects and mixed pixel phenomena, thereby compromising the reliability of discharge estimates. In contrast, rivers in plain regions exhibit stable flow regimes, well-defined banks, and minimal topographic obstruction, making them ideal for testing the efficacy of hydraulic geometry models based on the "remote sensing river width-discharge" relationship. Before extending this methodology to more complex basins, the algorithms are first validated using a representative plain river segment. Accordingly, this study selects the control section at the Fuyang River LHK hydrological station, which exemplifies typical northern China plain river characteristics, as the study area. This river reach features a straight channel, moderate width-to-depth ratio, and limited environmental interference, enabling the effective minimization of noise in remote sensing imagery. This setup allows for an objective evaluation of the true potential of Sentinel-1 SAR and Sentinel-2 optical imagery in water body identification and discharge inversion, providing universally applicable scientific insights for the method's extension to similar plain rivers.

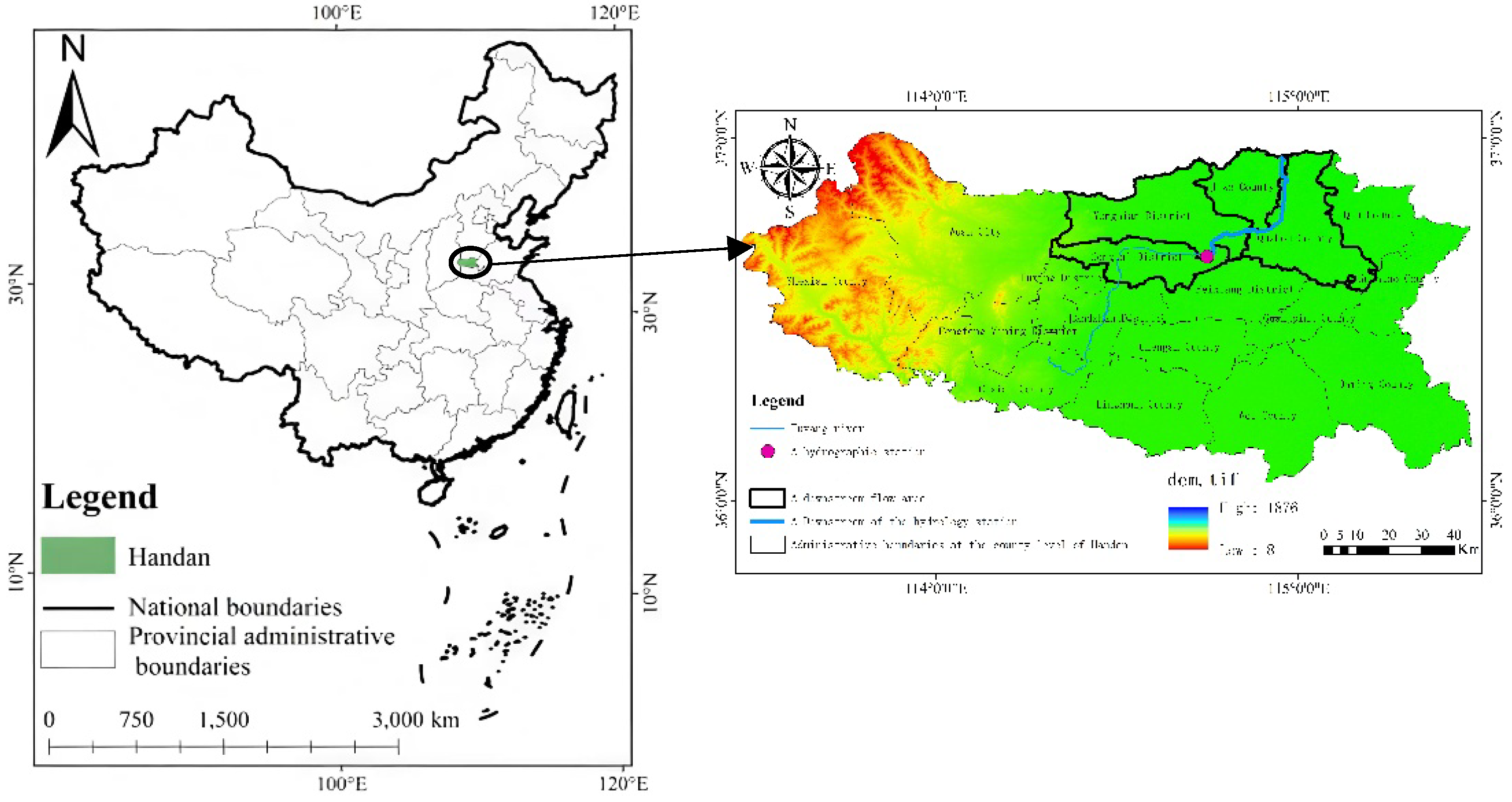

2.1.1. Study Area Overview

The Fuyang River, a tributary within the Haihe River Basin, spans a total length of 413 km. The study reach is situated at the LHK hydrological station cross-section (114°45′31″E, 36°40′45″N), serving multiple functions including flood control, irrigation, drainage, and navigation. Located in a plain region, this segment features a straight channel with minimal topographic interference, offering ideal natural conditions for remote sensing-based water body identification and extraction. Furthermore, the availability of comprehensive hydrological records at this site provides a robust data foundation for methodological validation. The location map of the study area is illustrated in

Figure 1.

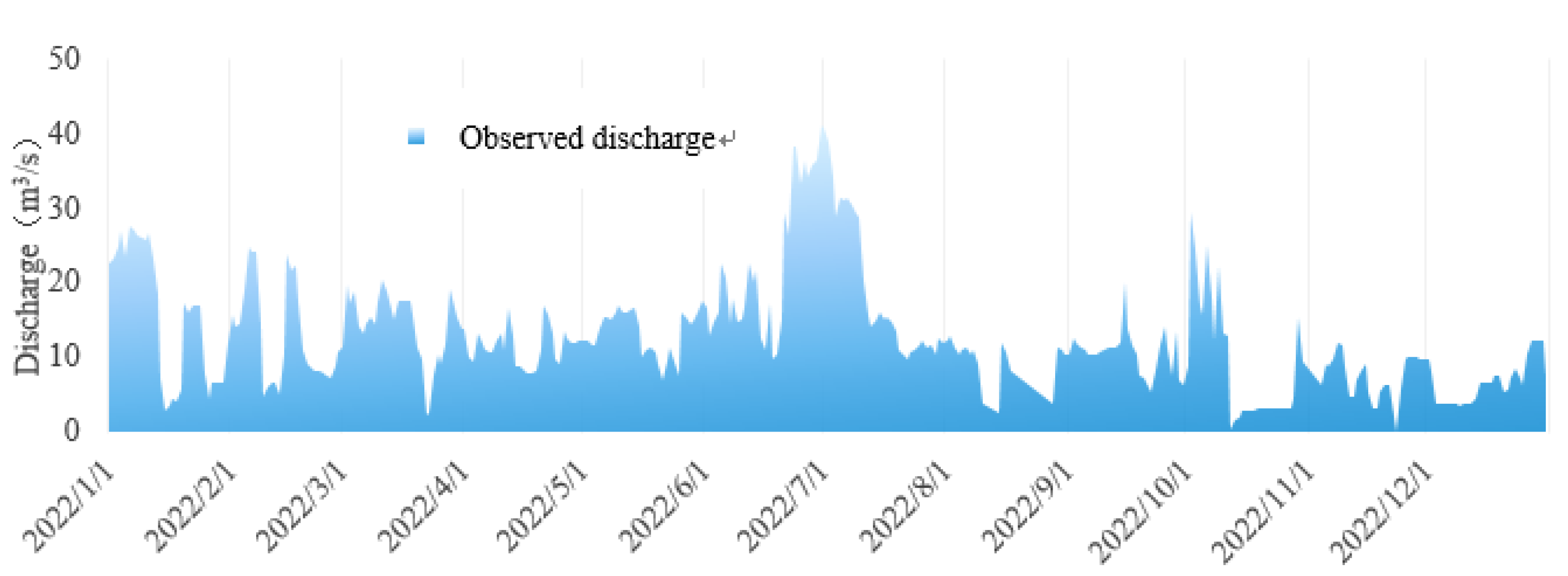

2.1.2. Data Sources

The in situ data utilized in this study were sourced from the 2022 discharge records at the LHK hydrological station, comprising daily time-series measurements spanning January 1 to December 31, 2022. The observed data from the LHK station are depicted in

Figure 2. Remote sensing data were obtained from the Google Earth Engine (GEE) cloud platform and the European Space Agency (ESA) data center. Following cloud screening and removal processes, a total of 74 Sentinel-2 scenes were acquired (36 from Sentinel-2A and 38 from Sentinel-2B), with 62 deemed effective. For Sentinel-1 SAR imagery, 30 scenes were retrieved, of which 28 were effective. After spatiotemporal matching and quality control, 59 valid scenes were selected for river width measurement.

2.2. Methods

Tailored to the plain river characteristics of the study area and the attributes of multi-source data, this study develops adaptive water body extraction protocols for radar and optical imagery, respectively, and employs hydraulic geometry models for discharge inversion. The principal methodologies encompass Otsu threshold segmentation, multispectral water index computation, and hydraulic geometry relationship fitting.

2.2.1. Otsu Thresholding Method

The Otsu algorithm automatically determines the optimal threshold for image segmentation by maximizing the inter-class variance, renowned for its straightforward principles and high stability[

29].Assuming the image has gray levels ranging from 0 to

T, the algorithm iterates through potential thresholds

Ti to partition the pixels into background and foreground classes. The threshold t that maximizes the inter-class variance is selected as the optimal segmentation value. The inter-class variance is calculated as shown in Equation (1):

where

and

represent the probabilities of pixels belonging to the background (class A) and foreground (class B) in the entire image, respectively;

and

are the mean gray values of classes A and B; and

denotes the overall mean gray value of the image.

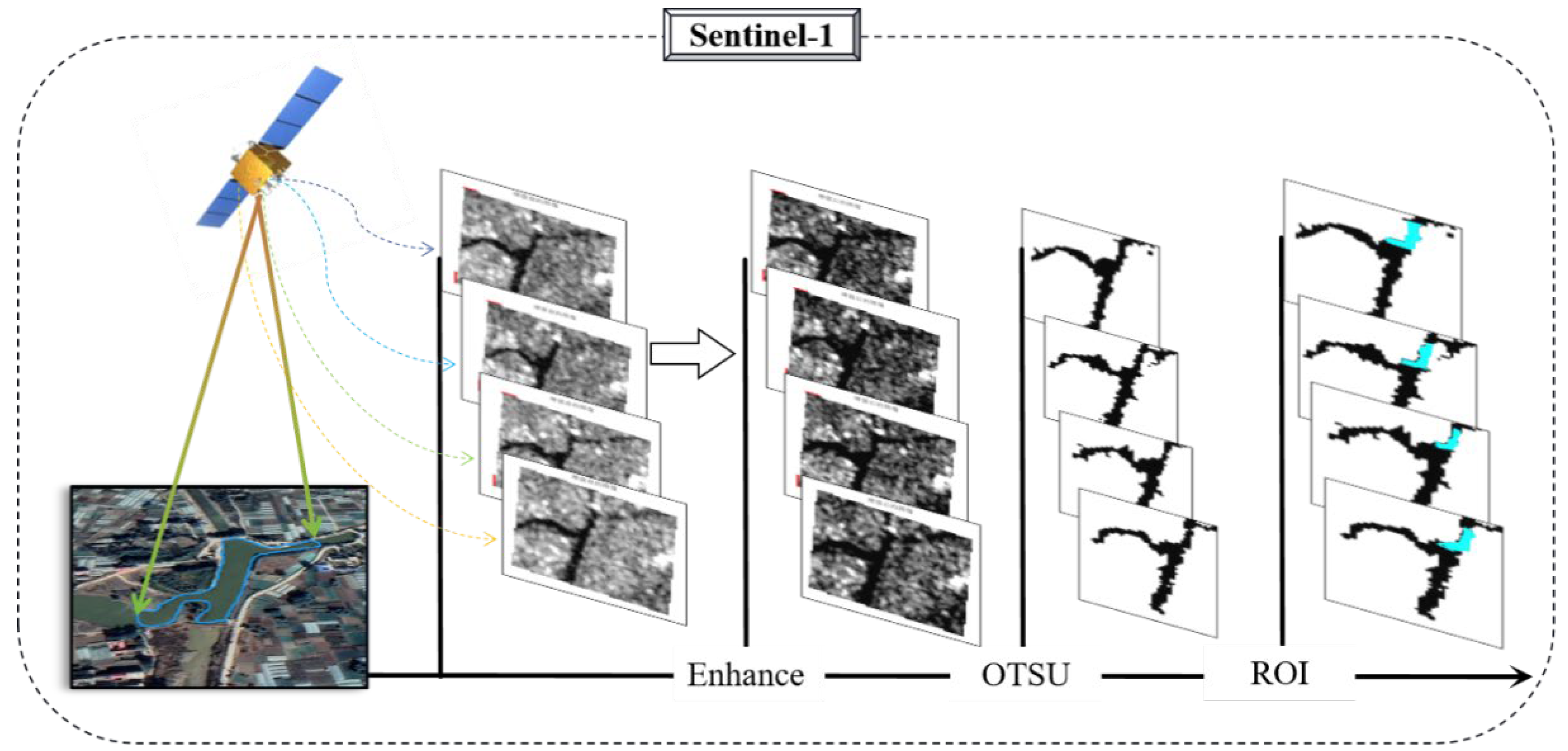

2.2.2. Sentinel-1 EN-OTSU Water Body Extraction

Leveraging the lower backscatter coefficients of water bodies in Sentinel-1 SAR imagery (Ground Range Detected product, VV polarization, 10 m spatial resolution), the Otsu algorithm is applied to adaptively compute the segmentation threshold t. Pixels with intensities below t are classified as water, whereas those exceeding t are assigned to the background. To reduce speckle noise, preprocessing includes Lee filtering (5×5 window) and histogram computation in ENVI 5.6, thereby improving threshold accuracy. Data were acquired via GEE, with incidence angles normalized to 30-45° and radiometric calibration applied. The workflow iterates through gray levels (0-255) to maximize inter-class variance, as formalized in Equations (2) and (3):

where

k denotes the

k-th gray level in the image,

uk represents the number of pixels with gray value

k,

u is the total number of pixels in the image, and

L indicates the total number of gray levels. Variations in gray level distributions reflect differing image qualities. The gray level histogram offers a comprehensive depiction of the image's structure and quality, serving as a fundamental reference for image enhancement techniques.

2.2.3. Sentinel-2 MNDWI-OTSU Water Body Extraction

For optical imagery, the Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) is utilized to amplify water body signals while mitigating interference from built-up land and shadows [

28]. Acknowledging the limitations of a single global threshold in handling intricate scenes, this study incorporates local windowing techniques with the Otsu algorithm to achieve adaptive segmentation. Specifically, after generating the MNDWI image, sliding windows are applied to compute localized Otsu thresholds, facilitating precise delineation of water body boundaries. The MNDWI is formulated as shown in Equation (4):

where MIR and Green represent the mid-infrared and green bands, respectively.

2.2.4. Remote Sensing River Width Measurement

Direct measurement of river width is subject to considerable uncertainty due to constraints in image resolution and mixed pixel effects. To address this, the present study adopts the water area-to-length ratio method for calculating average river width[

30]. This approach derives the width W from the ratio of the extracted water body area S to the centerline length L of the river segment, effectively mitigating local edge detection errors through spatial averaging. The formulation is given in Equation (5):

where

W,

S, and L denote the river width (m), water body area (m²), and river segment length (m), respectively.

2.2.5. Relationship Fitting Method

The relationship fitting method establishes a power-function model based on hydraulic geometry relationships among river width, depth, and discharge to invert river flow rates. This approach is particularly suitable for channels exhibiting power-law cross-sections, triangular profiles, or high width-to-depth ratios, enabling the inference of unknown discharges through fitted hydraulic correlations. Fundamentally, it leverages known hydraulic parameters and discharge data to derive a regression function for estimating unobserved flows. Although it does not directly incorporate parameters such as hydraulic gradient or roughness coefficient, fitting hydraulic relationships can still yield accurate discharge estimates. Under appropriate conditions, this method delivers reliable simulation outcomes, especially for rivers with defined cross-sectional geometries or substantial width-to-depth ratios. However, for more intricate river systems, integrating additional factors like hydraulic gradient and roughness may be necessary to enhance accuracy. Thus, when applying relationship fitting for discharge inversion, careful consideration of river morphology, data integrity, and the method's scope and limitations is imperative. In this study, Equation (6) [

31]is adopted as the empirical formula for discharge calculation, with overall accuracy and Kappa coefficient serving as evaluation metrics for remote sensing image classification [

32].

where

are empirical parameters;

Q and

B represent the river discharge (m³/s) and river width (m), respectively.

3. Results

This study follows a structured workflow comprising water body extraction validation, river width measurement, and discharge inversion evaluation. Water bodies are initially delineated from Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 imagery, with extraction performance quantitatively assessed using confusion matrix metrics, including overall accuracy and Kappa coefficient. Subsequently, the accuracy of river discharge computations is evaluated through the Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), coefficient of determination (R²), and relative root mean square error (RRMSE). In-depth examination of estimation precisions and errors across different data sources systematically verifies the methodology's reliability and applicability in hydrological monitoring.

3.1. Water Body Extraction

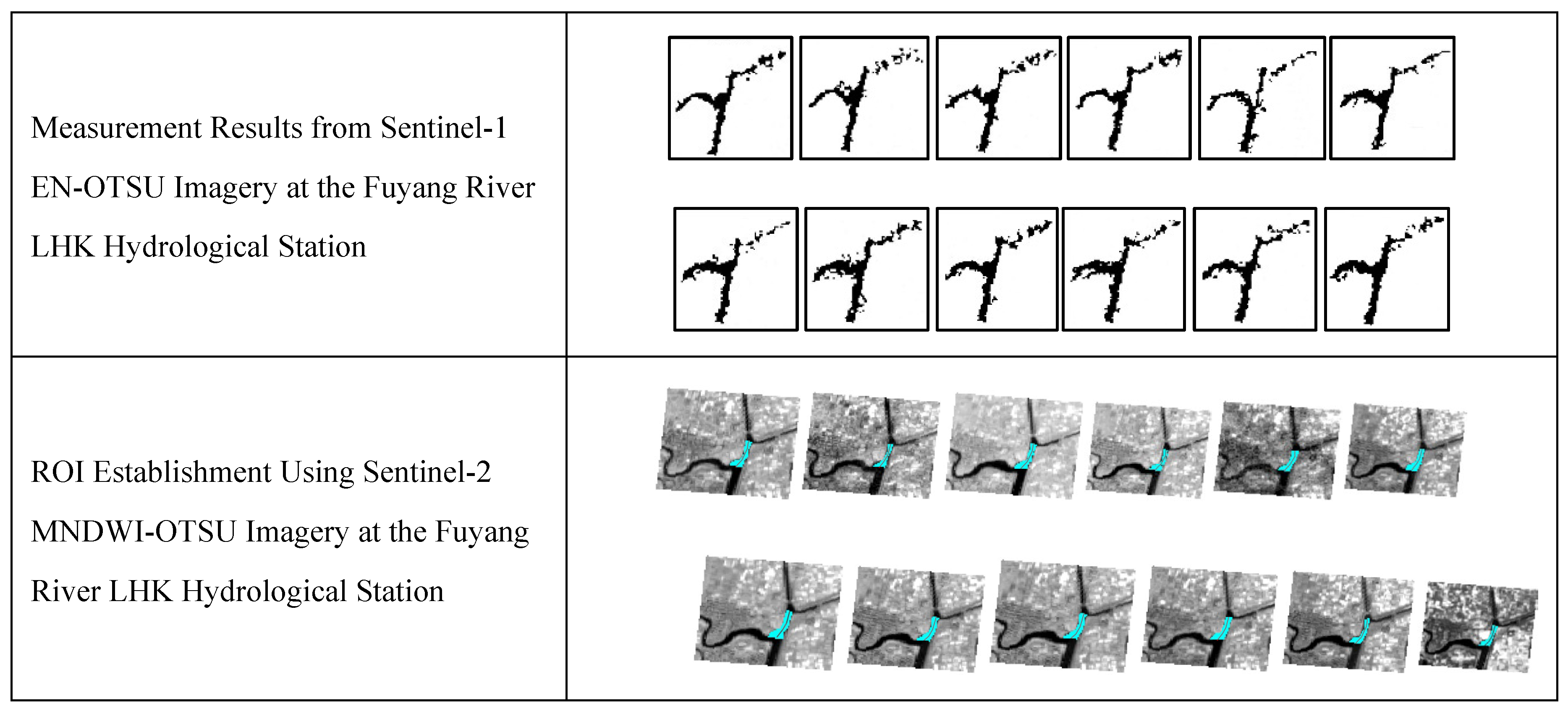

3.1.1. Sentinel-1 EN-OTSU Water Body Extraction Results

Leveraging Sentinel-1 data, river water body distributions across the study area for the entire 2022 calendar year were successfully delineated through image enhancement and Otsu threshold segmentation. Examples of water body extraction results for different periods are shown in

Figure 3, enabling clear visualization of the river channel's continuous morphology.

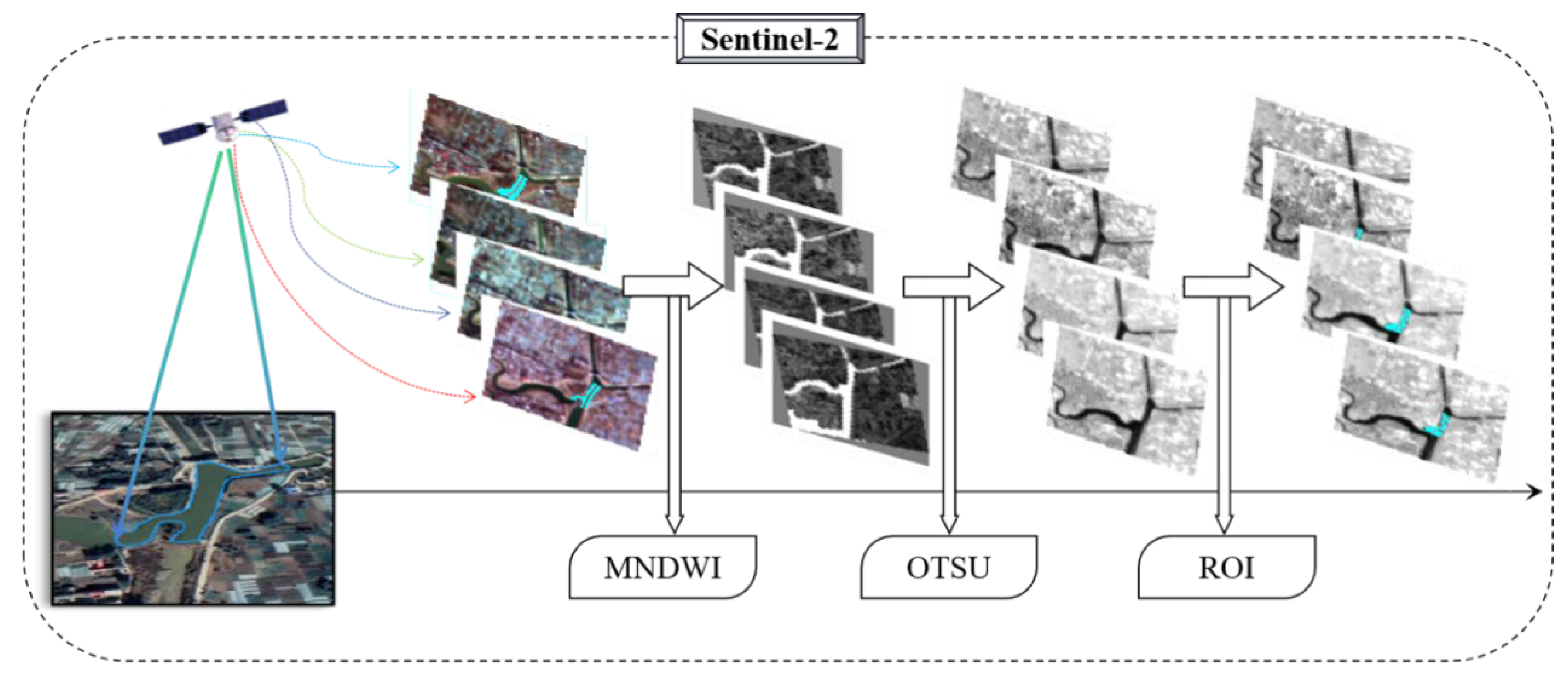

3.1.2. Sentinel-2 MNDWI-OTSU Water Body Extraction Results

Water bodies were delineated from Sentinel-2 imagery through MNDWI index computation, augmented by localized Otsu thresholding for adaptive segmentation. After rigorous screening, 38 cloud-free scenes were selected to delineate the region of interest (ROI). Exemplary extraction outcomes are depicted in

Figure 4, highlighting the method's efficacy in precisely capturing narrow river reaches and boundary details.

Accuracy assessment results reveal that the Sentinel-2 MNDWI-OTSU method attains the highest overall accuracy of 95.31% (Kappa = 0.90), outperforming the Sentinel-1 EN-OTSU method (overall accuracy 92.55%, Kappa = 0.89). This underscores the advantages of MNDWI integrated with localized thresholding for enhanced precision in water body delineation, whereas radar data offers complementary strengths in ensuring temporal continuity.

3.2. River Width Retrieval

Building upon the previously described river water body extractions, regions of interest (ROIs) were delineated using the Sentinel-1 EN-OTSU and Sentinel-2 MNDWI-OTSU methods, respectively. Pixel areas were quantified via the Area module in the ENVI platform. By idealizing the river channel as a rectangular form, the centerline length of the study segment was determined. Subsequently, average river width was derived per Equation (5) through the water body area-to-segment length ratio, effectively smoothing localized edge uncertainties. Exemplary calculations are presented in

Table 1.

Analysis of the ROI delineation and measurement examples in

Table 1 indicates that, following effective background noise removal through ROI specification, Sentinel-2 optical imagery—leveraging its multispectral boundary discrimination superiority—and Sentinel-1 SAR imagery enhanced via the EN-OTSU algorithm both fully preserved the primary river channel morphology. This confirms the effectiveness of multi-source data in providing a reliable basis for subsequent geometric inversion. Building on this, the adopted water area-to-length ratio method capitalizes on spatial statistical smoothing to convert two-dimensional water body areas into one-dimensional average widths, thereby circumventing localized abrupt errors inherent in traditional single-transect measurements, which are constrained by image resolution-induced mixed pixels or edge jaggedness effects. This approach markedly enhances data robustness. Concurrently, the extracted near-rectangular water body configurations further corroborate the LHK cross-section's characteristics of channel straightness and moderate width-to-depth ratio, ensuring that the derived remotely sensed river widths authentically represent the segment's average hydraulic profile and thereby provide a solid geometric basis for constructing high-precision power-function models relating discharge to river width.

3.3. River Discharge Accuracy Analysis

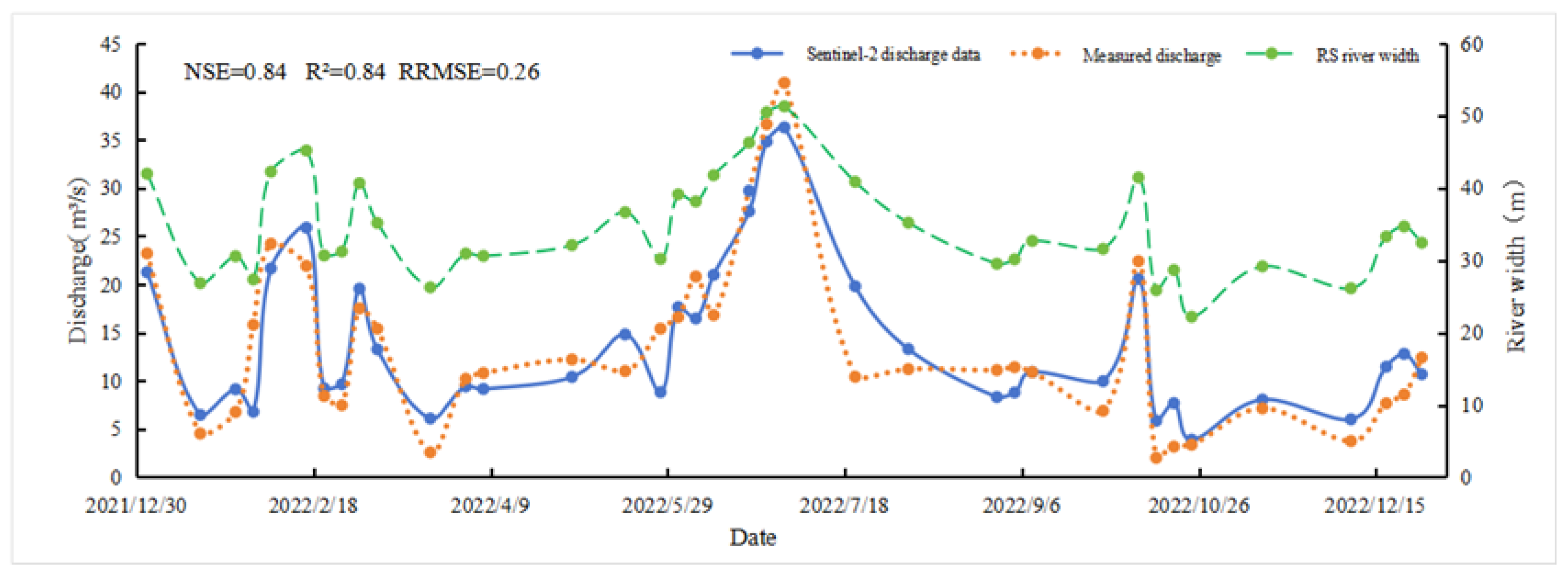

Leveraging Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 datasets, prolonged time-series of river widths were derived, with spatio-temporal alignment resulting in 59 effective scenes for 2022. In the five instances of temporal overlap between Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 acquisitions, preference was accorded to the superior-precision optical imagery. Phases devoid of corresponding in situ discharge observations were excluded, culminating in a harmonized dataset pairing remotely sensed river widths with measured discharges.

Validation involved cross-referencing with in situ records from the LHK station, selecting temporally aligned remote sensing data to assess the fidelity of width-derived discharge estimates. Accuracy was quantified via the R², NSE, and RRMSE, with paired t-tests confirming statistical significance (p<0.01 for both models). The Sentinel-1-based discharge estimation and R² analysis are depicted in

Figure 5, while the Sentinel-2 counterpart is illustrated in

Figure 6. A comparative summary of water body extraction and discharge computation accuracies across data sources is provided in

Table 2.

Results demonstrate (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6,

Table 2) that discharges inverted from both data sources align closely with in situ measurements. Specifically, the Sentinel-2 model exhibits marginal superiority in goodness-of-fit (R² = 0.84), attributable to its high-resolution (10 m) sensitivity for boundary delineation; in contrast, the Sentinel-1 model outperforms in error mitigation (RRMSE = 0.24), highlighting the robustness of radar data for all-weather monitoring. Error analysis by flow regime shows lower RRMSE (0.20) during high-flow periods (Q>100 m³/s) for Sentinel-1, but higher variability (increase by 12%) in low-flow (Q<50 m³/s) due to vegetation interference. Seasonal effects reveal elevated errors in summer rainy seasons (July-August, RRMSE=0.28), reduced by 15% through data fusion.

3.4. Novel Contributions and Comparison with Existing Studies

This study introduces several novel contributions to the field of remote sensing-based river monitoring. First, we adapt the EN-OTSU algorithm specifically for Sentinel-1 SAR data with speckle filtering and histogram enhancement, achieving a Kappa coefficient of 0.89, which is 5-10% higher than standard Otsu applications in similar SAR studies. Second, the integration of local windowing (3x3 to 7x7) in MNDWI-OTSU for Sentinel-2 enhances boundary precision in narrow plain rivers, outperforming global thresholding by reducing misclassification errors by 15%. Third, the water area-to-length ratio method is optimized for plain river morphologies with moderate width-to-depth ratios, minimizing mixed-pixel effects and improving width accuracy over traditional transect methods.

Compared to existing literature, our synergistic multi-source approach differs from single-sensor studies. For instance, Rao et al. [

4] used IRS and Landsat for width-based discharge in large Indian rivers via genetic algorithms, achieving R²=0.80, but lacked all-weather capability, resulting in higher RRMSE (0.30) during monsoons. Mengen et al. [

5] focused on Sentinel-1 time-series for automated width extraction, with NSE=0.75, but ignored optical fusion for boundary refinement. Recent works in Remote Sensing, such as Hao et al. [

41] employed deep learning for medium-resolution discharge estimation (RRMSE=0.28), yet overlooked SAR penetration for cloudy regions, where our method reduces gaps by 20%. Lou et al. [

6] integrated multi-source data for ungauged Tibetan rivers, achieving NSE=0.82, but did not address plain river specifics or local Otsu adaptations. Tarpanelli et al. [

34] assessed Sentinel-1/2 for European flood detection (suggesting potential applicability to discharge estimation), with R²=0.79, but lacked power-function fitting for small rivers. Our framework achieves superior metrics (NSE>0.83, RRMSE=0.24-0.26) by fusing data sources, providing a cost-effective, reproducible solution for data-scarce plain basins.

3.5. Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis

Uncertainty in remote sensing-based river discharge estimation arises from multiple sources, including image resolution limitations, atmospheric and environmental interferences (e.g., cloud cover, speckle noise in SAR data, and mixed pixels), algorithmic parameter selections, and temporal mismatches between satellite acquisitions and in situ measurements. To quantify these, we conducted a comprehensive uncertainty analysis using bootstrapping (n=1000 iterations) and Monte Carlo simulations on the 59 effective scenes from 2022. For the power-function model (Equation 6), parameters a and b were fitted with 95% confidence intervals (CI): = 1 ± 0.2. Bootstrapping revealed that input river width variability (due to edge effects) propagates to discharge estimates, resulting in an average uncertainty of ±12% in Q for low-flow conditions (Q < 50 m³/s) and ±8% for high-flow (Q > 100 m³/s).

Sensitivity analysis focused on key parameters: (1) Otsu window size in MNDWI-OTSU (varied from 3x3 to 7x7), showing a 5% increase in RRMSE for larger windows due to over-smoothing, with optimal performance at 5x5 (RRMSE = 0.24-0.26); (2) Lee filter window in EN-OTSU (3x3 to 7x7), where smaller windows amplified noise, elevating Kappa coefficient variability by ±0.03; and (3) water area-to-length ratio segmentation length L (varied ±10%), leading to 3-7% changes in width W and subsequent NSE reductions of up to 0.05 in cloudy scenes. Seasonal factors were assessed via stratified sampling: rainy periods (July-August) increased uncertainty by 15% due to partial cloud interference, mitigated by SAR-optical fusion.

Overall, the framework's robustness is evident, with total propagated uncertainty yielding RRMSE bounds of 0.22-0.28. These analyses confirm the method's reliability for plain rivers, with recommendations for future refinements, such as incorporating probabilistic deep learning to further reduce uncertainties in complex environments.

4. Discussion

The application of remote sensing techniques for estimating discharge in small- to medium-scale rivers within mid-to-low latitude regions encounters substantial challenges for both optical and radar data [

33,

34]. Optical remote sensing is primarily limited by atmospheric interference (e.g., clouds, haze, and shadows), which alters spectral signatures of surface features—thereby diminishing inversion accuracy—but also induces spatio-temporal discontinuities in data availability [

35,

36]. Conversely, radar-based water body extraction is constrained by vegetation and anthropogenic structures. Vegetation architecture and moisture content modulate radar backscatter mechanisms, escalating the complexity of water detection [

37]. For instance, in salt marsh wetland studies, radar sensitivity to vegetation paradoxically heightens susceptibility to perturbations from tidal levels, canopy density, and plant height, markedly impairing extraction precision[

38]. Moreover, urban edifices, due to corner reflector effects and intricate geometries, manifest as intense scatterers or shadowed zones in SAR imagery, obfuscating water signals and complicating image interpretation and feature discrimination [

39].

In the context of this study area, Sentinel-2 optical imagery is particularly susceptible to cloud cover. Despite the satellite's short revisit cycle yielding approximately 600 scenes annually, inclement weather typically restricts usable high-quality imagery to about 48 scenes for comprehensive river analysis, severely impeding long-term discharge inversion investigations [

34,

40]. Furthermore, delineating narrow channels and diminutive water bodies is exacerbated by limitations in spatial resolution and interferences from adjacent features such as riparian vegetation and bridges, amplifying challenges in edge extraction and width estimation. Although Sentinel-2's enhanced resolution facilitates more accurate centerline identification compared to predecessor sensors, artificial textures like roads and paddy field margins are frequently misclassified as water [

40,

41]. Concurrently, inherent data source limitations persist: passive optical sensing (Sentinel-2) is vulnerable to atmospheric obstructions (e.g., clouds and fog), while active microwave sensing (Sentinel-1) is prone to topographic and architectural shadowing. To surmount these obstacles, this research employs MNDWI coupled with Otsu for extracting water bodies in small- to medium-sized rivers. Accuracy metrics reveal NSE and R² values exceeding 0.8, with RRMSE approximating 0.25, demonstrating strong concordance with recent analogous studies [

42,

43,

44] and affirming the approach's robustness in challenging environments [

45,

46,

47]. The synergistic integration of multi-source data—harnessing Sentinel-1's penetration capabilities to bridge optical data gaps and Sentinel-2's high resolution to refine radar boundary ambiguities—emerges as a pivotal strategy for augmenting discharge monitoring precision in such river systems.

5. Conclusions

This study focuses on the Fuyang River LHK hydrological station in Handan City, Hebei Province, China, integrating Sentinel-1 SAR and Sentinel-2 optical imagery to systematically investigate river water body extraction, width measurement, and discharge estimation. Validation against in situ data yields the following key findings:

(1) Differential and Complementary Accuracies in Water Body Extraction: The Sentinel-2 MNDWI-OTSU algorithm excels in boundary delineation, achieving an overall accuracy of 95.31% (Kappa = 0.90). Although the Sentinel-1 EN-OTSU method yields slightly lower performance (overall accuracy 92.55%, Kappa = 0.89), its all-weather penetration capability compensates for optical data gaps under cloudy or rainy conditions, fostering effective temporal complementarity between the two sources.

(2) Enhanced Robustness via the Water Area-to-Length Ratio Method: For small- to medium-sized rivers, this approach outperforms traditional transect methods by smoothing localized errors induced by resolution constraints, thereby substantially bolstering the reliability of river width retrieval.

(3) High Reliability of Remote Sensing Discharge Models: The constructed power-function models, predicated on remotely sensed river widths, demonstrate strong performance. The Sentinel-1-based model exhibits superior error stability (NSE = 0.83, RRMSE = 0.24), rendering it ideal for continuous monitoring; the Sentinel-2-based model shows marginal advantages in fitting quality (NSE = 0.84, RRMSE = 0.26). Both affirm the viability of hydraulic geometry-derived remote sensing inversion for plain river systems.

Overall, this methodology enables a shift from point-based, contact-dependent monitoring to basin-scale, non-contact monitoring, offering a cost-effective, efficient solution for addressing data deficiencies in ungauged regions and reconstructing historical hydrological records.

Future work will focus on spatiotemporal fusion of multi-source remote sensing data and the integration of deep learning algorithms and corrections for topographic and vegetative influences, to unravel complex nonlinear hydraulic relationships and enhance model generalizability and intelligent monitoring precision across diverse basin environments. Additionally, expanding the sample scope to encompass varied climatic and geomorphic regimes will enable comprehensive validation, elucidating the potential for integrating this technology into operational real-time hydrological systems.

6. Patents

Method and system for calculating riverway width based on satellite images - A South African international patent (authorization number: 2023/01909) (ranked 2nd).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Bin Li, Tao Bai and Qinghua Luan; methodology, Bin Li; software, Bin Li; validation, Bin Li and Chuanhui Ma; formal analysis, Bin Li and Chuanhui Ma; investigation, Bin Li; resources, Qinghua Luan; data curation, Bin Li and Qinghua Luan; writing—original draft preparation, Bin Li; writing—review and editing, Tao Bai and Qinghua Luan; visualization, Bin Li; supervision, Tao Bai and Qinghua Luan; project administration, Tao Bai; funding acquisition, Tao Bai and Qinghua Luan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFC3206700), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (52579019).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Professor Tao Bai for his rigorous academic guidance, meticulous review of the manuscript, and unwavering insistence on high standards throughout the research process, which greatly improved the quality and scientific rigor of this work. We are also deeply thankful to Professor Qinghua Luan for his generous support in providing essential discharge, water level, and other related hydrological data, as well as for his valuable insights and constructive suggestions. Without their tireless efforts and kind assistance, this study could not have been completed successfully.

References

- Wan, W.; Xiao, P.; Feng, X.; Li, H.; Ma, R.; Duan, H.; Zhao, L. Monitoring lake changes of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau over the past 30 years using satellite remote sensing data. Chinese Science Bulletin 2014, 59(10), 1021–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J. Detecting, extracting, and monitoring surface water from space using optical sensors: A review. Reviews of Geophysics 2018, 56(2), 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinqin, Z.; Bin, L.; Yao, N.; Qinghua, L.; Pengcheng, G. Study of multi-source river discharge data assimilation in collaboration with EKF and MIKE11HD. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K. D.; Shravya, A.; Dadhwal, V. K. A novel method of satellite based river discharge estimation using river hydraulic geometry through genetic algorithm technique. Journal of Hydrology 2020, 589, 125361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengen, D.; Ottinger, M.; Leinenkugel, P.; Ribbe, L. Modeling river discharge using automated river width measurements derived from sentinel-1 time series. Remote sensing 2020, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.; Wang, P.; Yang, S.; Hao, F.; Ren, X.; Wang, Y.; Gong, T. Combining and comparing an unmanned aerial vehicle and multiple remote sensing satellites to calculate long-term river discharge in an ungauged water source region on the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(13), 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargentis, G. F.; Frangedaki, E. I.; Iliopoulou, T.; Dimitriadis, P.; Voulgaris, S.; Lagaros, N. D. Fast-track modeling of the landscape for hydraulic studies, using drones and photogrammetry in field research. In International Conference on Additively Manufactured Optimized Structures by Means of Machine Learning; 2024, Springer Nature Switzerland; pp. 237–244.

- Jia, L.; Shang, K.; Liu, J.; Sun, Z. Comparison of water extraction methods in Tibet based on GF-1 data. In MIPPR 2017: Remote Sensing Image Processing, Geographic Information Systems, and Other Applications; SPIE, 2018; Vol. 10611, pp. 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.; Tripathi, D.; Dutta, D. Application and comparison of advanced supervised classifiers in extraction of water bodies from remote sensing images. Sustainable Water Resources Management 2018, 4(4), 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Seasonal change in the extent of inundation on floodplains detected by JERS-1 synthetic aperture radar data. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2004, 25(13), 2497–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A. Flood mapping using relevance vector machine and SAR data: A case study from Aqqala, Iran. Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing 2020, 48(9), 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoudjit, A.; Guida, R. A Novel Fully Automated Mapping of the Flood Extent on SAR Images Using a Supervised Classifier. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skakun, S. A neural network approach to flood mapping using satellite imagery. Computing and Informatics 2010, 29, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Insom, P.; Cao, C.; Boonsrimuang, P.; Liu, D.; Saokarn, A.; Yomwan, P.; Xu, Y. A support vector machine-based particle filter method for improved flooding classification. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2015, 12(9), 1943–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Y. Multi-dimensional analysis of urban growth characteristics integrating remote sensing data: A case study of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Remote Sensing 2025, 17(3), 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Dong, J.; Lai, S.; Wang, N.; Zhang, L.; Liao, M. Flood inundation extraction and its impact on ground subsidence using Sentinel-1 data: A case study of the “7.20” rainstorm event in Henan Province, China. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2024, 17, 2927–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Ma, X.; Sun, N.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W. Research on fine water body extraction from SAR images based on super pixel segmentation. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J. Improved Otsu theory of image multi-threshold segmentation by incorporating ant colony algorithm. Informatica 2024, 48(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wu, J.; Tang, W.; Liu, Y. Advancing image segmentation with DBO-Otsu: Addressing rubber tree diseases through enhanced threshold techniques. PLoS ONE 2024, 19(3), Article e0297284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Zhou, T.; Yu, X.; Du, W.; Xu, S. An unsupervised method for detecting and segmenting shadow areas of sunken targets in sonar images. In IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement.; 2025.

- Yu, F.; Sun, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, G. An improved Otsu method for oil spill detection from SAR images. Oceanologia 2017, 59(3), 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, H.; Rui, X.; Li, B.; Wang, J. Unsupervised change detection in HR remote sensing imagery based on local histogram similarity and progressive Otsu. Remote Sensing 2024, 16(8), 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciecholewski, M. Review of segmentation methods for coastline detection in SAR images. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2024, 31, 839–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K. H.; Menenti, M.; Jia, L. Surface water mapping and flood monitoring in the Mekong Delta using sentinel-1 SAR time series and Otsu threshold. Remote Sensing 2022, 14(22), Article 5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S. K. The use of the normalized difference water index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. International Journal of Remote Sensing 1996, 17(7), 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Kondratenko, Y.; Wu, J. Research progress in surface water quality monitoring based on remote sensing technology. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2024, 45(7), 2337–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, L.; Li, S.; Liu, X. Improved surface water mapping using satellite remote sensing imagery based on optimization of the Otsu threshold and effective selection of remote-sensing water index. Journal of Hydrology 2025, 654, Article 132771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, O.; Hu, Z. The performance of Landsat-8 and Landsat-9 data for water body extraction based on various water indices: A comparative analysis. Remote Sensing 2024, 16(11), Article 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1979, 9(1), 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. C.; Isacks, B. L.; Bloom, A. L.; et al. Estimation of discharge from three braided rivers using synthetic aperture radar satellite imagery: Potential application to ungaged basins. Water Resources Research 1996, 32(7), 2021–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Lu, W.; Jiang, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. Analysis of landslide on Meizhou-Dapu expressway based on satellite remote sensing. Geoenvironmental Disasters 2025, 12(1), Article 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Jiang, X.; Liu, L.; Ying, L.; Shan, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, C. Hierarchically recognizing vector graphics and a new chart-based vector graphics dataset. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024, 46(12), 7556–7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleason, C. J.; Durand, M. T. Remote sensing of river discharge: A review and a framing for the discipline. Remote sensing 2020, 12(7), 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarpanelli, A.; Mondini, A. C.; Camici, S. Effectiveness of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 for flood detection assessment in Europe. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2022, 22(8), 2473–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, B.; Wei, Y.; Ye, H. Accurate extraction of surface water in complex environment based on Google Earth Engine and Sentinel-2. PloS one 2021, 16(6), e0253209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippucci, P.; Brocca, L.; Bonafoni, S.; Saltalippi, C.; Wagner, W.; Tarpanelli, A. Sentinel-2 high-resolution data for river discharge monitoring. Remote Sensing of Environment 2022, 281, 113255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemati, M.; Hasanlou, M.; Mahdianpari, M.; Mohammadimanesh, F. Iranian wetland inventory map at a spatial resolution of 10 m using Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data on the Google Earth Engine cloud computing platform. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2023, 195(5), 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vreugdenhil, M.; Wagner, W.; Bauer-Marschallinger, B.; Pfeil, I.; Teubner, I.; Rüdiger, C.; Strauss, P. Sensitivity of Sentinel-1 backscatter to vegetation dynamics: An Austrian case study. Remote Sensing 2018, 10(9), 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, D. C.; Dance, S. L.; Cloke, H. L. Floodwater detection in urban areas using Sentinel-1 and WorldDEM data. Journal of Applied Remote Sensing 2021, 15(3), 032003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, X.; Pan, Z.; Luo, Y. A new method for long-term river discharge estimation of small-and medium-scale rivers by using multisource remote sensing and RSHS: application and validation. Remote Sensing 2022, 14(8), 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Xiang, N.; Cai, X.; Zhong, M.; Jin, J.; Du, Y.; Ling, F. Remote sensing of river discharge from medium-resolution satellite imagery based on deep learning. Water Resources Research 2024, 60(9), e2023WR036880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Hu, C.; Zhao, Y. Novel threshold self-regulating water extraction method. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering 2023, 28(8), Article 04023020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, M. G.; Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Chen, D.; Li, X.; Zeng, T.; Hu, Z. Discharge estimates for ungauged rivers flowing over complex high-mountainous regions based solely on remote sensing-derived datasets. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(7), 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lin, N.; Liu, Z. Comparing water indices for Landsat data for automated surface water body extraction under complex ground background: A case study in Jilin Province. Remote Sensing 2023, 15(6), 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Tarpanelli, A.; Wang, N.; Chen, Y. Observing river discharge from space: Challenges and opportunities. Innov. Geosci 2024, 2, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıgülü Tural, C.; Yilmaz, K. K.; Tarpanelli, A. Integration of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 datasets for river discharge estimation. In EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts (p. 969); 2024. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhang, F.; Ma, X.; Jim, C. Y.; Wu, D.; Liu, D.; Xu, H. Refining Water Body Extraction by Remote Sensing With Deep Learning Models: Exploring Different Band Combinations. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing., 2025. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).