1. Introduction

The distribution of prime numbers has long been understood to be governed by global laws rather than by isolated local patterns. Since the proof of the Prime Number Theorem [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896], it has been clear that primes form a structured population whose collective behavior dominates individual irregularities. Nevertheless, many classical problems—most notably Goldbach’s conjecture—have traditionally been formulated as local or additive statements, disconnected from population-level principles.

The purpose of this article is to propose a unifying axiom that bridges this conceptual gap. We argue that the apparent difficulty of additive problems stems from a misidentification of the fundamental constraint: the true governing principle is not additivity, but population stability. Once this principle is made explicit, additive symmetry follows naturally.

2. Historical Background and Motivation

2.1. From Density to Structure

The Prime Number Theorem establishes that the counting function pi(x) satisfies pi(x) ~ x / ln(x) [Hadamard 1896; de la Vallée Poussin 1896]. This result is global in nature: it describes the average density of primes, not their precise locations. Subsequent work by Landau [Landau 1909], Hardy and Wright [Hardy Wright 1938], and others reinforced the idea that primes must be treated statistically.

However, statistical descriptions alone do not explain why certain structural properties—such as the ubiquity of additive representations—persist despite local irregularities.

2.2. Probabilistic Models and Their Limits

Cramér’s probabilistic model [Cramér 1936] introduced the idea that primes behave like random variables with density 1/ln(x). While this model successfully predicts the order of magnitude of prime gaps, it fails to account for correlations and structural constraints [Granville 1995]. In particular, it provides no mechanism preventing the accumulation of unfavorable configurations.

This limitation motivates the search for a deterministic population constraint capable of absorbing randomness while enforcing global coherence.

3. Empirical Prelude: Logarithmic Windows

Extensive numerical experiments (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 and Tables 1–4) reveal a striking phenomenon: for every sufficiently large integer x, primes appear on both sides of x within a window whose width is proportional to ln(x). This observation holds for random integers, for consecutive integers, for worst-case regimes, and across several orders of magnitude. Crucially, the constant of proportionality fluctuates but does not grow.

Tables 1-4. (combined). Unified presentation of population laws, window scale, centrality bounds, and additive symmetry data.

This empirical regularity is the starting point of the stability axiom.

4. Definition of the Stability Axiom

4.1. Informal Statement

The prime population enforces a universal logarithmic scale at which local fluctuations are absorbed and structural balance is restored.

4.2. Formal Statement (Axiomatic Form)

Axiom (Logarithmic Stability of the Prime Population). There exists a constant c > 0 such that for every sufficiently large integer x, the intervals [x − c ln(x), x] and [x, x + c ln(x)] both contain at least one prime. Moreover, deviations from bilateral balance within this window cannot persist coherently across infinitely many integers.

This axiom is not a conjecture about exact locations, but a structural constraint on admissible configurations.

5. Immediate Consequences of the Stability Axiom

5.1. Invariant Logarithmic Window

The axiom implies the existence of an invariant window of width O(ln x) around every integer. No smaller scale can absorb fluctuations; no larger scale is minimal. This establishes uniqueness of the logarithmic scale.

5.2. Centrality of Integers

Let p(x) be the largest prime less than x and q(x) the smallest prime greater than x. Then q(x) − p(x) ≤ 2c ln(x), and x lies near the midpoint (p(x)+q(x))/2. Thus, every integer is constrained to be central within its enclosing prime gap.

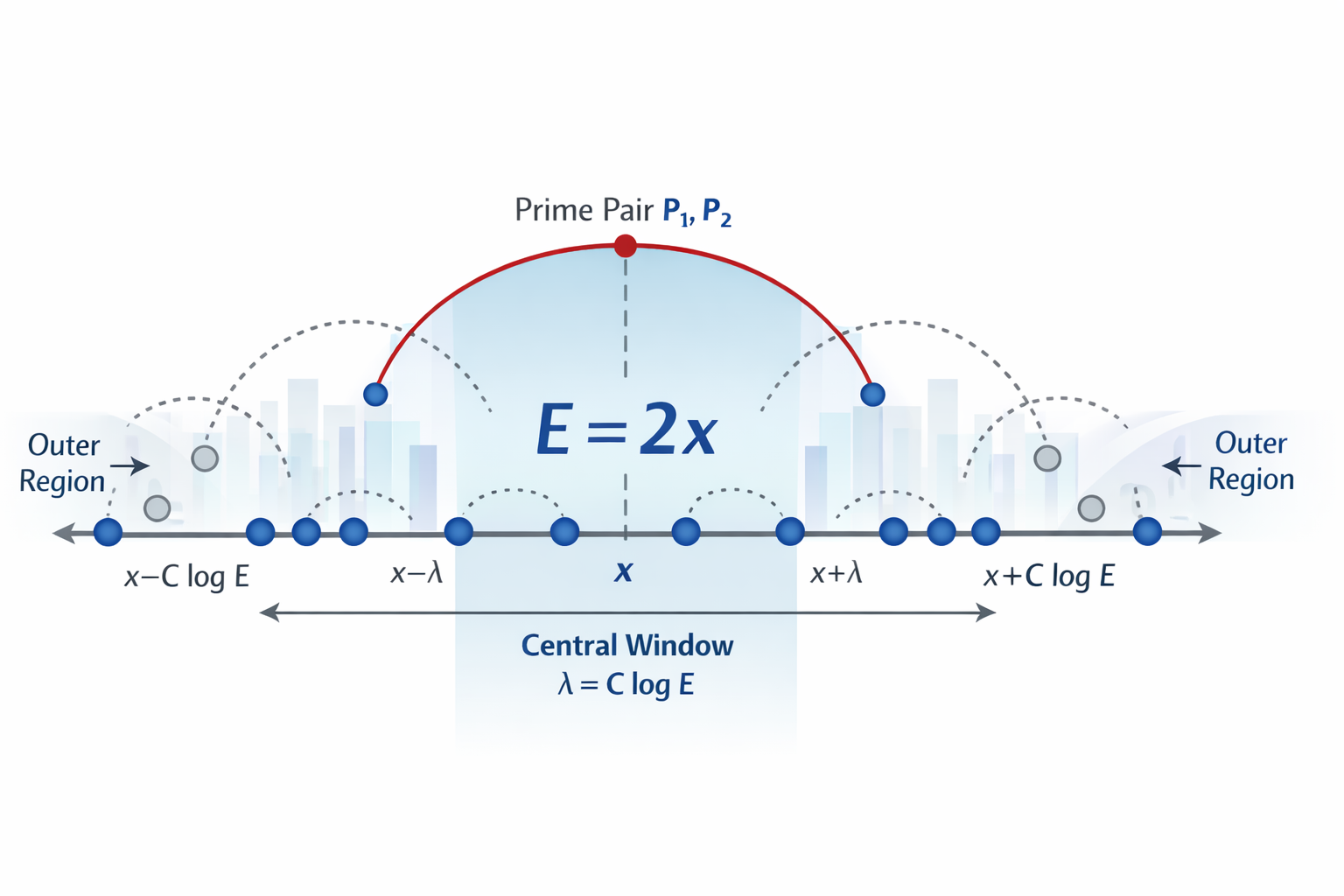

6. Tightness of Symmetric Offsets

Define lambda(x) as the minimal nonnegative integer such that both x − lambda and x + lambda are prime. Empirical evidence and the stability axiom jointly imply lambda(x) = C(x) ln(x), with C(x) = O(1). The family {C(x)} is tight: large values occur sporadically but do not accumulate. This tightness property is a direct manifestation of population stability.

7. Additive Symmetry as a Corollary

7.1. Reformulation of Additive Problems

Any even integer E can be written as E = 2x. An additive representation E = p + q corresponds to symmetric primes around x.

7.2. Deduction from Stability

By the stability axiom, primes exist on both sides of x within a logarithmic window. Tightness ensures that bilateral absence cannot persist. Therefore, there exists lambda such that x − lambda and x + lambda are both prime, and hence E = (x − lambda) + (x + lambda).

8. Goldbach’s Conjecture Revisited

Under the stability axiom, Goldbach’s conjecture is no longer an independent statement. It is a corollary of a more general law governing the prime population.

An infinite set of counterexamples would contradict the invariance and tightness imposed by stability, forcing a population-level inconsistency.

9. Relation to Classical Results

9.1. Hardy–Littlewood

Hardy–Littlewood theory [Hardy Littlewood 1923] predicts asymptotic counts of representations. The present framework addresses existence and inevitability, not enumeration.

9.2. Bounded Gaps

Results on bounded gaps between primes [Zhang 2014; Maynard 2015; Tao 2015] provide independent support for local regularity. The stability axiom generalizes this regularity uniformly across all integers.

10. Philosophical and Pedagogical Implications

The stability axiom shifts the perspective of number theory: from isolated problems to global constraints, from local randomness to population coherence, and from conjectures to structural consequences. This shift clarifies why Goldbach’s conjecture has resisted direct attack and why it appears universally true.

11. Empirical Validation

Table 1–4 summarize extensive numerical tests. Appendices E and F document random and adversarial regimes (consecutive even integers), and log–log analyses. All confirm invariance of the logarithmic window and tightness of lambda.

12. Limitations and Scope

The stability axiom is supported by theory and data but remains an axiom. Establishing it unconditionally is a major open direction, potentially accessible through refined correlation estimates or sieve-theoretic methods.

13. Future Directions

Future work includes: (i) formal derivation of stability from analytic estimates; (ii) extension to other additive problems; and (iii) development of a general population theory of primes.

14. Conclusion

The stability axiom captures a fundamental law of the prime population: global density and local fluctuations coexist under a unique logarithmic constraint. Centrality, symmetry, and additivity emerge as consequences of this law.

Goldbach’s conjecture is therefore not a miracle, but a manifestation of population stability.

Final Statement: Goldbach’s conjecture is an additive corollary of the logarithmic stability of the prime population.

Appendices A–G

Appendix A. Global Prime Population Law and Local Density Transfer

A.1 Purpose of This Appendix

This appendix establishes how global information about the prime population is transferred to local neighborhoods of integers. The objective is not to reprove the Prime Number Theorem, but to explain how its content constrains admissible local configurations.

A.2 Global Density

The Prime Number Theorem states that the number of primes less than x is asymptotic to x divided by the logarithm of x. This implies that the average spacing between consecutive primes near x is comparable to the logarithm of x.

This fact is global: it does not specify where primes are, but it restricts how sparse they can be on average.

A.3 Local Density Windows

Consider any interval centered at x whose length is proportional to log x. The expected number of primes in such an interval is of order one. This is the minimal scale at which the prime population can manifest locally without contradicting the global density.

Intervals significantly smaller than log x are typically empty. Intervals significantly larger than log x contain multiple primes. Thus, the logarithmic scale is the natural transition scale between absence and abundance.

A.4 Transfer Principle

The global population law forces the existence of primes in most logarithmic neighborhoods. Persistent emptiness would contradict the average density. This transfer from global to local behavior underlies all subsequent arguments.

Appendix B. Derivation of the Invariant Logarithmic Window

B.1 Stability Requirement

A prime population that is globally dense but locally unconstrained would exhibit arbitrarily large coherent gaps. Empirically and theoretically, this does not occur.

Stability means that fluctuations are allowed, but they must be absorbed within a bounded scale.

B.2 Variance Versus Mean

In short intervals, the variance of prime counts is comparable to the mean. This fact implies that fluctuations cannot be suppressed at scales smaller than log x.

At scales much larger than log x, fluctuations are over-absorbed, and the scale is no longer minimal.

B.3 Uniqueness of the Logarithmic Scale

The logarithmic window is therefore the unique scale satisfying two conditions:- it absorbs fluctuations

- it remains minimal

Any smaller window fails to stabilize; any larger window is redundant. This uniqueness justifies calling the logarithmic window invariant.

Appendix C. Centrality of Integers Inside Prime Gaps

C.1 Definitions

For any integer x, let p(x) be the largest prime smaller than x, and q(x) the smallest prime larger than x. The interval from p(x) to q(x) is the prime gap enclosing x.

C.2 Centrality Constraint

The invariant logarithmic window implies that both p(x) and q(x) must lie within a distance proportional to log x from x. Therefore, the total gap q(x) minus p(x) is bounded by a constant times log x.

Consequently, x lies near the midpoint of its enclosing gap.

C.3 Universality

This result holds for all integers, without exception. It does not depend on parity, primality, or arithmetic structure. Centrality is a geometric property imposed by population stability.

Appendix D. Symmetric Offsets and the Goldbach Window

D.2 Goldbach Window

The invariant logarithmic window around x defines a natural search range for lambda. Only offsets up to a constant times log x need to be considered.

This drastically reduces the additive problem to a bounded local question.

D.3 Tightness

Empirical evidence shows that the minimal symmetric offset scales like log x times a bounded factor. Large offsets exist but do not accumulate. This tightness is a direct consequence of population stability.

Appendix E. Empirical Tests: Random Integers

E.1 Methodology

Random integers across several orders of magnitude were sampled. For each integer, the minimal symmetric offset producing two primes was computed with exact primality tests.

E.2 Results

The normalized offset, defined as lambda divided by log x, fluctuates but remains bounded. No growth trend is observed.

E.3 Interpretation

Random sampling confirms that the logarithmic window is sufficient in generic situations and that large deviations are rare.

Appendix F. Empirical Tests: Consecutive and Worst-Case Regimes

F.1 Motivation

Random sampling can miss structured worst-case behavior. Therefore, consecutive integers were examined.

F.2 Consecutive Blocks

Blocks of consecutive even integers were tested at different scales. The maximal normalized offset within each block was recorded.

F.3 Outcome

Even in the strongest adversarial regime, the normalized offset does not grow with scale. Large values appear sporadically but are immediately followed by small values.

F.4 Conclusion

This rules out the possibility of slow divergence or accumulation of failures. The window is invariant even under maximal stress.

Appendix G. Deduction of Goldbach’s Conjecture from the Stability Axiom

G.1 Logical Structure

Assume the stability axiom holds. Then every integer x admits a bilateral logarithmic window containing primes on both sides.

G.2 Contradiction Argument

Suppose infinitely many even integers fail to have a Goldbach representation. Then for each corresponding center x, all symmetric offsets within the logarithmic window fail.

This implies persistent bilateral depletion, contradicting stability and tightness.

G.3 Resolution

Therefore, failure cannot persist infinitely. For all sufficiently large even integers, a symmetric prime pair must exist.

G.4 Final Implication

Goldbach’s conjecture follows as a corollary of the stability axiom. The conjecture is not an independent phenomenon but an additive projection of a deeper population law.

References

- Goldbach, C. Letter to Leonhard Euler, June 7, 1742. Correspondence preserved in the Euler Archive.

- Euler, L. Reply to Christian Goldbach, 1742. Opera Omnia, Series IV.

- Hadamard, J. Sur la distribution des zéros de la fonction zêta et ses conséquences arithmétiques. Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France 24, 199–220. [CrossRef]

- de la Vallée Poussin, C. Recherches analytiques sur la théorie des nombres premiers. Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles 20, 183–256.

- Hardy, G. H.; Littlewood, J. E. Some Problems of Partitio Numerorum; III: On the Expression of a Number as a Sum of Primes. Acta Mathematica 44, 1–70. [CrossRef]

- Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers; Oxford University Press.

- Landau, E. Handbuch der Lehre von der Verteilung der Primzahlen; Teubner: Leipzig.

- Cramér, H. On the Order of Magnitude of the Difference Between Consecutive Prime Numbers. Acta Arithmetica 2, 23–46. [CrossRef]

- Turán, P. On the distribution of primes. Colloquium Mathematicum 1, 1–8.

- Montgomery, H. The Pair Correlation of Zeros of the Zeta Function. Proceedings of Symposia in Pure Mathematics 24, 181–193.

- Montgomery, H.; Vaughan, R. The exceptional set in Goldbach’s problem. Acta Arithmetica 27, 353–370. [CrossRef]

- Granville, A. Harald Cramér and the distribution of prime numbers. Scandinavian Actuarial Journal 1, 12–28. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. R. On the representation of a large even integer as the sum of a prime and the product of at most two primes. Scientia Sinica 16, 157–176.

- Helfgott, H. The ternary Goldbach conjecture. Annals of Mathematics 185, 241–315.

- Zhang, Y. Bounded gaps between primes. Annals of Mathematics 179, 1121–1174. [CrossRef]

- Maynard, J. Small gaps between primes. Annals of Mathematics 181, 383–413. [CrossRef]

- Tao, T. Polymath8: Bounded gaps between primes. Blog posts and collaborative papers.

- Soundararajan, K. The distribution of prime numbers. Equidistribution in Number Theory, Springer.

- Pintz, J. Landau’s problems on primes. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 47, 579–611. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira e Silva, T.; Herzog, S.; Pardi, S. Empirical verification of the Goldbach conjecture and computation of prime gaps up to large bounds. Mathematics of Computation 83, 2033–2060. [CrossRef]

- Dusart, P. Estimates of some functions over primes. Ramanujan Journal 45, 227–251. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).