3.1. Motivation for Stochastic Modelling of Trust

In

Section 2 we introduced the continuum limit of the probabilistic network model on a hierarchical directed acyclic graph (DAG) and obtained the degenerate logistic–diffusion equation

where

x denotes the depth in the hierarchy and

is the probability that agents at depth

x have adopted the assertion

A by time

t. In this deterministic setting,

u quantifies local social conformity or conviction with respect to a fixed assertion. A notion of

trust—a robust, long-lived disposition to accept or reject information from a given source or about a given assertion—does not yet appear as an independent dynamical object; it emerges only once the intrinsic randomness of social interactions and information flows around the hierarchical backbone (

15) is taken into account.

Real hierarchical societies are exposed to irregular signals and heterogeneous micro-events that cannot be captured by a purely deterministic evolution. Even if the averaged network structure is well approximated by

and

, belief formation at a given depth layer is subject to randomness in the structure and timing of micro-interactions, the arrival of external messages (media, rumours, exogenous shocks), and fluctuations in the size and responsiveness of each depth level. These sources of uncertainty induce random deviations of

from the deterministic trajectory (

15). The long-time effect of such fluctuations is precisely what we interpret as the emergence of stable “trust” and “distrust” phases along the hierarchy, in the spirit of noise-induced transitions in extended systems [

21,

22,

23].

To model these fluctuations it is natural to perturb (

15) by a stochastic term. A purely

additive noise, say

with

a space–time white noise, would attribute the same level of randomness to depth layers with almost complete consensus (

or

) and to layers that are internally split (

). This is at odds with microscopic and phenomenological intuition: in nearly unanimous layers the aggregated state should be relatively insensitive to sporadic perturbations, whereas in strongly polarised layers small events can cause substantial shifts of the local average. Additive noise also tends to push

u outside the physically meaningful interval

, unless one enforces artificial reflecting or absorbing boundaries.

These considerations point instead to a multiplicative noise whose amplitude depends on the current state u. A simple microscopic picture is to regard each depth layer as a finite group of n agents with independent Bernoulli states , where denotes acceptance of A and rejection, and to set

If , then for large n one has , which is maximal for and vanishes for or . In the continuum description this suggests that the natural scale of spontaneous fluctuations of at depth x should be proportional to . We interpret as a local measure of polarisation or internal tension in that layer: when the layer is almost unanimous ( or ) the polarisation , and hence the effective noise level, are negligible; when the layer is sharply divided (), the polarisation and the effective noise are maximal.

We are thus led to adopt a multiplicative stochastic perturbation with amplitude proportional to

. In the stochastic extension of (

15) we shall use noise terms of the form

, where

is a global noise intensity and

is a space–time noise, interpreted in the Stratonovich sense in time, as is natural for smooth approximations of coloured noise [

22,

24]. Our guiding principle can be summarised as follows:

Random fluctuations of the belief field should be maximal in internally polarised (split) layers of the hierarchy and should vanish in layers with near-complete consensus. Accordingly, the amplitude of stochastic forcing is taken proportional to the local polarisation .

In the subsequent subsections we show that this choice of multiplicative noise, combined with the Stratonovich interpretation, generates an effective double-well potential for u and gives rise to two robust phases of the belief field, and , which we interpret as persistent distrust and trust, respectively.

3.2. Local Stochastic Dynamics at a Single Depth Layer

To analyse how trust emerges from noisy belief dynamics at a fixed hierarchical depth, we freeze the depth coordinate and focus on a single layer of the DAG. We consider a scalar process

representing the coarse-grained probability that agents in this layer have adopted the assertion

A by time

t. In the deterministic continuum model (

15), this quantity evolves according to a local logistic law driven by the effective amplification rate

. At a fixed depth, where

can be approximated by a constant

, the dynamics reduces to the ordinary differential equation

which describes the monotone increase of the local adoption probability from its initial value

towards the saturated state

, interpreted here as the formation of a stable trusting attitude towards the assertion within the layer.

To incorporate the random microstructure of social interactions at this depth, we perturb (

16) by multiplicative noise. Following the motivation in

Section 3.1, we choose the noise amplitude proportional to

, so that fluctuations are strongest in internally polarised layers and vanish under near-complete consensus. The resulting local stochastic dynamics is given by the Stratonovich stochastic differential equation

where

is the noise intensity,

is a standard Wiener process, and ∘ indicates Stratonovich integration in time [

22,

24].

The multiplicative factor

in (

17) has a direct probabilistic interpretation. When

or

, the layer is nearly unanimous in rejecting or accepting the assertion, internal polarisation is small, and the amplitude of stochastic perturbations is correspondingly suppressed. When

, the layer is sharply split, the polarisation

is maximal, and even small random informational events can produce appreciable shifts in the aggregate belief. Dynamically, the choice of the factor

ensures that both the deterministic drift and the stochastic forcing vanish at the endpoints

and

: the interval

is invariant, and the boundary states act as natural absorbing configurations. Once a layer has fully consolidated in distrust (

) or trust (

), infinitesimal fluctuations cannot immediately move it away from that state.

In the following subsections we show that, under the Stratonovich interpretation, (

17) is equivalent to an Itô diffusion with an additional noise-induced drift term. This effective drift can be written in gradient form with respect to a double-well potential, and endows

and

with the meaning of two robust stochastic phases of the local belief field. These phases correspond, respectively, to persistent distrust and persistent trust at the level of a single depth layer.

3.3. Stratonovich–Itô Conversion and Noise-Induced Drift

The local stochastic dynamics at a single depth layer was introduced in

Section 3.2 as the Stratonovich SDE

where

is the local amplification rate,

is the noise intensity,

is a standard Wiener process, and ∘ denotes Stratonovich integration in time [

22,

24]. To analyse the induced drift and the long-time behaviour of

it is convenient to rewrite (

18) in Itô form.

For a one-dimensional SDE of the generic Stratonovich type

the equivalent Itô equation is

with

. In the present setting

and

, so that

and

Substituting into (

20) yields the Itô form of (

18),

Thus the Stratonovich multiplicative noise generates an additional,

noise-induced drift term proportional to

.

For subsequent use we introduce the effective drift

and the noise amplitude

Equation (

21) can then be written succinctly as

The structure of the noise-induced drift becomes transparent if we introduce the quartic “polarisation potential”

A direct computation gives

so that the noise-induced part of the drift can be written as

Hence

It is therefore natural to represent the drift as the negative derivative of an effective potential

,

where the integration constant in

V is irrelevant for the dynamics.

The first term in (

29),

is entirely due to the Stratonovich multiplicative noise. For

it defines a symmetric double-well landscape:

vanishes at

and

and attains its maximum at

, so that

has minima at

and

and a local maximum at

. When the logistic term

is small or absent, this noise-induced contribution dominates and

exhibits two nearly equivalent wells centred at

and

, separated by a barrier near

. In this regime the states

and

become two robust stochastic phases of the local belief field, corresponding to persistent distrust and persistent trust, while the intermediate state

is unstable and statistically suppressed.

The deterministic term

in (

22) adds an asymmetric component to

via the integral in (

29). It does not destroy the double-well structure created by the noise but

tilts the potential, making one well deeper than the other. Thus both

and

remain locally stable configurations, but one of them becomes statistically preferred, with higher occupation probability and longer residence times in the presence of noise. The balance between the deterministic tilt, controlled by

r, and the noise-induced double well, controlled by

, determines whether the layer is more likely to consolidate in distrust or in trust and how easily it can switch between these phases under random perturbations.

The associated Fokker–Planck equation for the density

of

on

[

22,

25] admits a quasi-stationary solution

whose shape is governed by the potential

. In the regime where the noise-induced polarisation term dominates the deterministic bias

r,

develops two pronounced peaks near

and

and a pronounced minimum around

. This structure is illustrated in

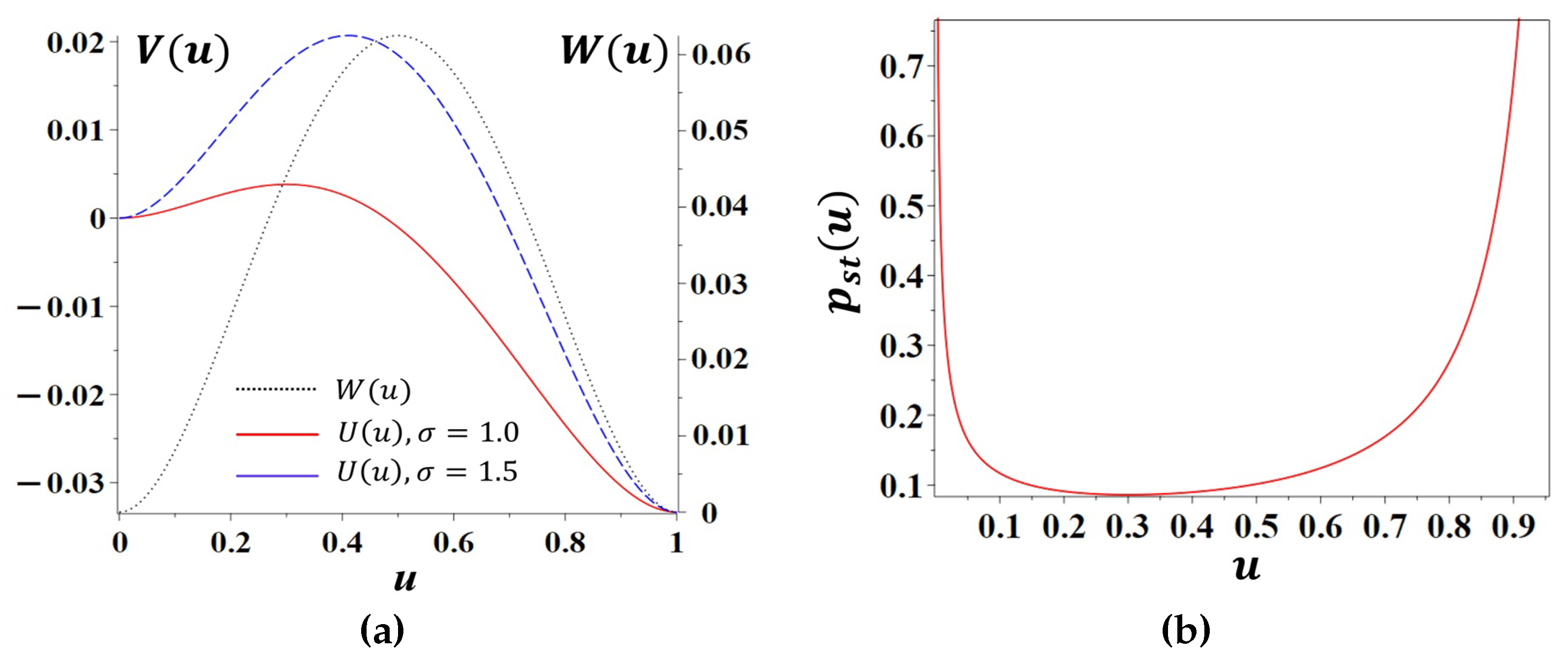

Figure 1.

Figure 1 summarises the message of the local stochastic trust model. The polarisation potential

and the effective potential landscape encoded in

both single out the consensus configurations

and

as preferred states, while the internally polarised configuration

is energetically and probabilistically disfavoured. Accordingly, a single hierarchical layer does not remain in a permanently split state: it tends to resolve internal polarisation by collapsing either into a stable trust phase (

) or into a stable distrust phase (

), with noise-induced transitions between the two phases occurring on exponentially large time scales. These local bistable dynamics form the microscopic building blocks for the spatial domain formation and phase diagrams discussed in the subsequent subsections.

3.4. Fokker–Planck Equation and Stationary Distribution

The Itô form of the local stochastic dynamics at a single depth layer was obtained in

Section 3.3 as

with drift and diffusion

as in (

22)–(

23). The evolution of the density

of

on

is governed by the associated Fokker–Planck equation

supplemented by boundary conditions at

and

[

22,

25]. In the present setting both

and

vanish at the endpoints, so these boundaries are natural candidates for absorbing states. On very long time scales the true stationary distribution of (

30) is therefore concentrated at

and

, corresponding to persistent distrust and persistent trust in the layer.

To understand how the robust phases

and

emerge and how they are separated by an unstable intermediate region, it is convenient to consider the

stationary Fokker–Planck equation in the interior

under the assumption of vanishing probability flux. This corresponds either to reflecting regularisations at the endpoints or to a quasi-stationary description conditioned on not having yet reached

or

. Denoting the stationary density by

, stationarity

and zero stationary flux give

Equation (

33) is a first-order linear ODE that admits the standard explicit solution (see, e.g., [

25])

where

is a normalising constant whenever the integral converges.

Using (

31), we have

The integral in (

34) is elementary and can be evaluated in closed form. Since the explicit expression is somewhat cumbersome, we relegate its full derivation to Appendix A and only summarise the structure here. The stationary density on

can be written as

where the effective potential

is a smooth function incorporating both the noise-induced double-well structure and the deterministic logistic tilt. More precisely,

contains a quartic contribution inherited from the potential

in (

29), together with additional logarithmic terms arising from the state-dependent diffusion coefficient

.

In the regime where the noise-induced part of the drift dominates the deterministic term (for instance, when

r is small compared to

), the leading contribution to

is proportional to

, so that

for some

and a slowly varying prefactor

that remains bounded and non-vanishing on

. The qualitative shape of (

36) is that of a

double-peaked density:

attains local maxima near

and

and a local minimum near

. Thus, for a single depth layer, the noisy dynamics (

18) admits two preferred configurations: one in which almost all agents persistently reject the assertion (

) and another in which almost all agents persistently accept it (

), see

Figure 1(

b). The intermediate state

, in which the layer is sharply divided, is statistically suppressed: it corresponds to the top of the effective potential barrier and plays the role of an unstable “saddle” between the two phases.

The parameters

r and

control the relative weight of these phases and the height of the barrier separating them. When

is large and

r is small, the noise-induced double well is nearly symmetric: the two peaks of

have comparable height, and the layer has roughly symmetric chances to reside in a high-trust or high-distrust configuration, with rare noise-driven transitions between them, cf. Kramers-type transitions in double-well potentials [

25,

26]. When

is not negligible, the deterministic logistic term

tilts the effective potential

in favour of trust: the well near

becomes deeper and more probable, while the well near

becomes shallower and less frequently visited. In this regime the layer still possesses two locally stable phases, but persistent trust dominates in the stationary statistics, and distrust appears mainly as a metastable configuration that can be overcome by fluctuations.

Thus, at the level of a single depth layer, the Fokker–Planck analysis confirms the picture suggested by the drift representation in

Section 3.3: Stratonovich multiplicative noise with amplitude

generates an effective double-well potential for the local trust variable

u, with robust phases concentrated near

and

and a probabilistically suppressed intermediate state around

.

While the stationary density

in

Figure 1 describes the long-run distribution over the trust level

u, it is also instructive to visualise typical sample paths of the local process (

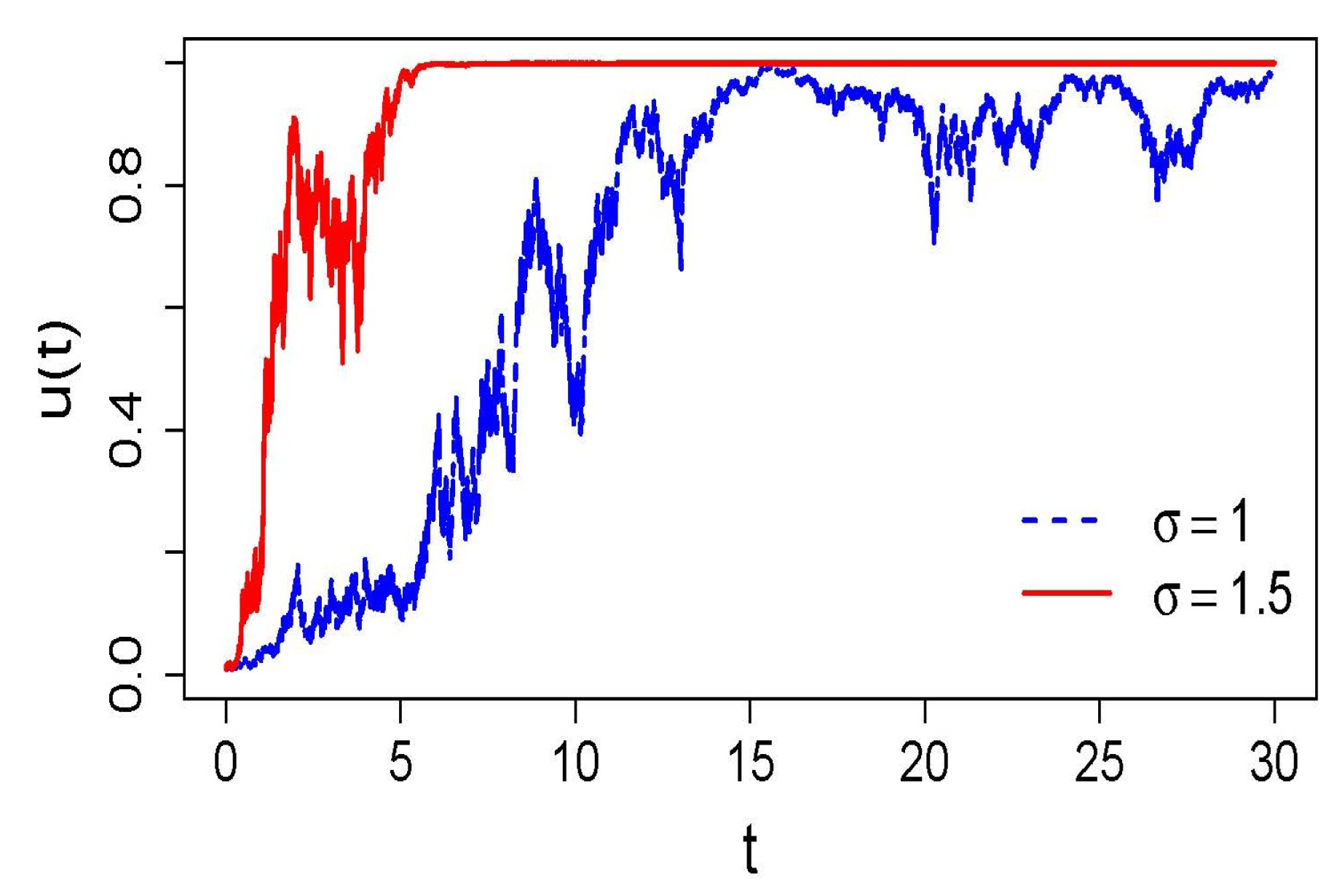

30). The next figure shows numerically simulated trajectories for two noise intensities, illustrating how the same double-well landscape leads to very different escape times from the distrusting phase and different fluctuation patterns near full trust.

Figure 2 highlights the temporal manifestation of the two phases identified by the Fokker–Planck analysis. In the weak-noise regime, a layer may spend a very long time in the vicinity of

before a sufficiently large fluctuation drives it across the potential barrier into the trusting phase

, after which it undergoes only relatively small fluctuations around near-consensus. As

increases, the effective barrier becomes easier to overcome, leading to much earlier entry into the trust well and stronger short-time variability near

. In the hierarchical setting, such local episodes of slow escape from distrust and subsequent consolidation in trust form microscopic building blocks for the spatial patterns and domain dynamics discussed in the following subsections, where many layers interact along the depth axis of the hierarchy.

3.5. Field-Theoretic MSRJD Formulation of Noisy Trust Dynamics

We now return to the spatially extended setting and reintroduce the depth coordinate

of the hierarchical DAG. The deterministic continuum limit of the network model is given by the degenerate logistic–diffusion equation (

15), in which

denotes the adoption probability (local social conformity) at depth

x. To incorporate random fluctuations as discussed in

Section 3.1–

Section 3.4, we augment (

15) by a multiplicative noise term with amplitude proportional to the local polarisation

, interpreted in the Stratonovich sense in time. The resulting SPDE reads

where

is the global noise intensity and

is a Gaussian white noise with covariance

.

As in the local analysis, it is convenient to convert (

37) to Itô form before constructing the field-theoretic representation. The Stratonovich–Itô correction acts pointwise in

x and produces the same noise-induced drift as in

Section 3.3. Thus, in Itô form we obtain

with deterministic part

and noise-induced contribution

identical to the local term in (

22). The function

encodes, in the continuum setting, the effective double-well structure derived in

Section 3.3 and is responsible for the emergence of robust local phases

and

at each depth.

To analyse rare events, nucleation of domains of trust and distrust, and large-scale fluctuations in the extended system, it is natural to use the Martin–Siggia–Rose–Janssen–De Dominicis (MSRJD) field-theoretic formalism [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. In this approach one introduces an auxiliary response field

and represents the statistics of (

38) by a functional integral over paths

weighted by an action

. Formally, starting from (

38), imposing the dynamics via a functional Dirac delta and integrating out the Gaussian noise

yields the MSRJD action

where

is given by (

39) and

is the observation horizon. The first term in (

41) enforces the deterministic part of the SPDE through the response field

, while the quadratic term in

is the direct outcome of integrating over Gaussian noise with multiplicative amplitude

.

Crucially, the deterministic functional

in (

41) contains exactly the same effective drift and noise-induced potential as those obtained from the Stratonovich–Itô conversion and the Fokker–Planck analysis in

Section 3.3–

Section 3.4. In particular,

encodes the double-well structure associated with the quartic term

, rendering

and

locally stable configurations of the belief field and

an unstable saddle. The MSRJD formulation therefore does not change the underlying dynamics; it recasts the same noisy trust model in a form well suited for the systematic treatment of fluctuations and rare events.

Heuristically, functional variation of (

41) with respect to

reproduces the Itô SPDE (

38), while variation with respect to

u yields adjoint (instanton) equations describing the most probable paths associated with rare transitions between the trust and distrust phases. The Fokker–Planck equation (

32) and its stationary solution (

35) describe the same dynamics at the level of probability densities for

at fixed depth. Thus the Itô Langevin formulation (

38), the Fokker–Planck description, and the MSRJD action (

41) are mutually consistent and complementary perspectives on the same stochastic model of trust formation in hierarchical societies.

From the modelling standpoint, the MSRJD framework is particularly useful in two contexts. First, it provides a natural language for analysing

large deviations and

nucleation events, in which a small domain of trust (or distrust) spontaneously appears within a background phase and either collapses or grows into a macroscopic region along the depth axis; in the weak-noise limit such events are governed by saddle points of (

41). Second, the MSRJD action is the starting point for renormalisation-group analyses in higher-dimensional settings, where geometric fluctuations and long-range correlations may substantially modify the effective propagation and pinning of trust and distrust fronts. In the present work we use the MSRJD representation primarily as a conceptual bridge between the microscopic noise model and the emergent bistable potential structure; a more detailed study of instantons, nucleation rates and coarse-grained effective theories is deferred to future work and is briefly outlined in

Appendix B.

3.6. Phase Selection and Social Interpretation of Trust/Distrust Phases

The analysis of the local SDE (

18) and its Fokker–Planck equation (

32) shows that multiplicative Stratonovich noise with amplitude

generates an effective double-well structure for the belief variable

at a fixed depth layer. Dynamically, the boundary states

and

act as two robust attractors of the stochastic dynamics (persistent distrust and persistent trust of the assertion within the layer), while the intermediate region near

is unstable and statistically disfavoured. We now make this phase-selection picture explicit and connect it to the social interpretation of trust and distrust.

At the level of a single depth layer, the Itô SDE (

30) describes a one-dimensional diffusion on

with absorbing endpoints. Let

be the first hitting time of

,

and let

be the probability that a trajectory starting from

is absorbed at

rather than at

,

It is standard [

25,

32] that

solves the boundary-value problem

with drift

and diffusion coefficient

given by (

31). Although the explicit solution of (

42) is cumbersome, its qualitative dependence on

,

r, and

is clear. When the noise-induced double-well potential dominates (e.g. for small

r and moderate

),

is strongly curved: for

slightly above

the absorption probability at

is close to one, whereas for

slightly below

it is close to zero, reflecting the unstable nature of the intermediate region and the strong attraction of the endpoints. When

is sufficiently large compared to

, the deterministic logistic term tilts the effective potential towards trust, and

becomes biased in favour of

, so that even initial conditions with

may have a substantial chance to end in the trusting phase. Thus, for an individual layer, the noisy dynamics induces a

probabilistic phase selection: starting from an internally mixed configuration, the layer ultimately consolidates either into distrust (

) or into trust (

), with selection probabilities determined by

and the parameters

.

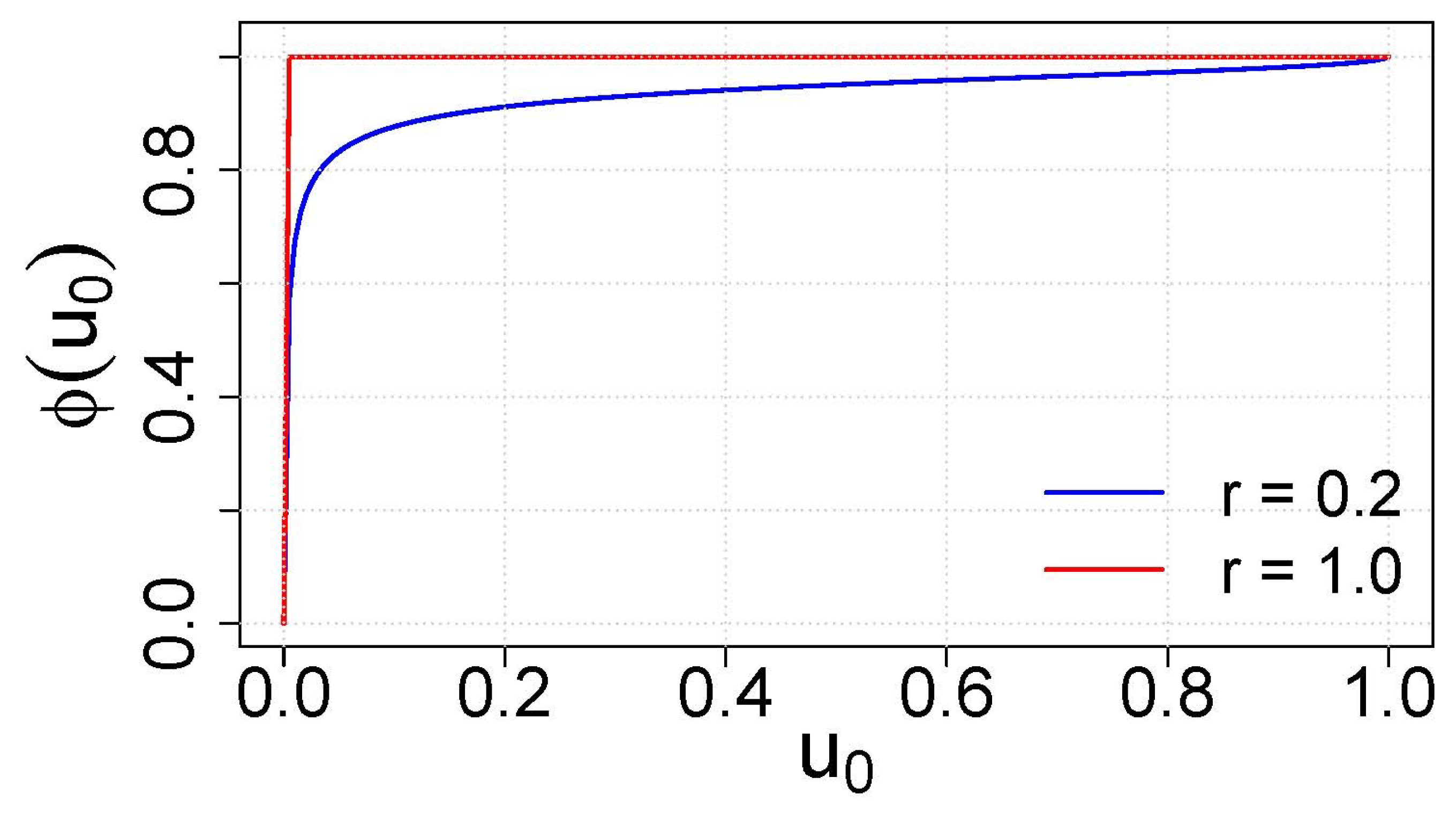

To illustrate these phase-selection probabilities quantitatively, we solve the boundary-value problem (

42) numerically for a fixed noise level

and two values of the amplification rate

r. The resulting hitting probabilities for the trusting phase are shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 confirms the strong tendency of the local process to end in the trusting phase. In the weakly biased case

, the curve

still exhibits a gradual increase as

moves away from the fully distrusting state, reflecting some residual sensitivity to the initial trust level. When

r is increased to

, the graph is essentially saturated at

except in an extremely small neighbourhood of

, indicating that even layers starting with very low trust almost surely converge to

. From a social perspective, this means that in a sufficiently favourable informational environment distrust becomes only metastable, while trust is the overwhelmingly preferred long-run outcome at the level of a single layer.

In the spatially extended model (

38) along the depth axis

x, this local bistability is coupled to degenerate diffusion via the term

. For an initial profile

that contains regions of intermediate values (polarised layers), the combined effect of spatial coupling, local double-well structure, and multiplicative noise produces a

mosaic of trust and distrust along the hierarchy. In regions where

is biased towards low values and the local tilt

is weak, the dynamics drives the field towards the distrust phase

; in regions where

is biased towards high values and/or

is sufficiently positive, the field is driven towards the trust phase

. At intermediate depths, where competing influences balance, the system develops narrow transition zones where

passes sharply from values close to 0 to values close to 1. These zones act as

domain walls or fronts separating stable trusting and distrusting regions, and their motion, pinning, and nucleation are governed by the interplay between degenerate diffusion, spatially varying

, and noise level

, in analogy with front dynamics and domain coarsening in bistable media [

33,

34].

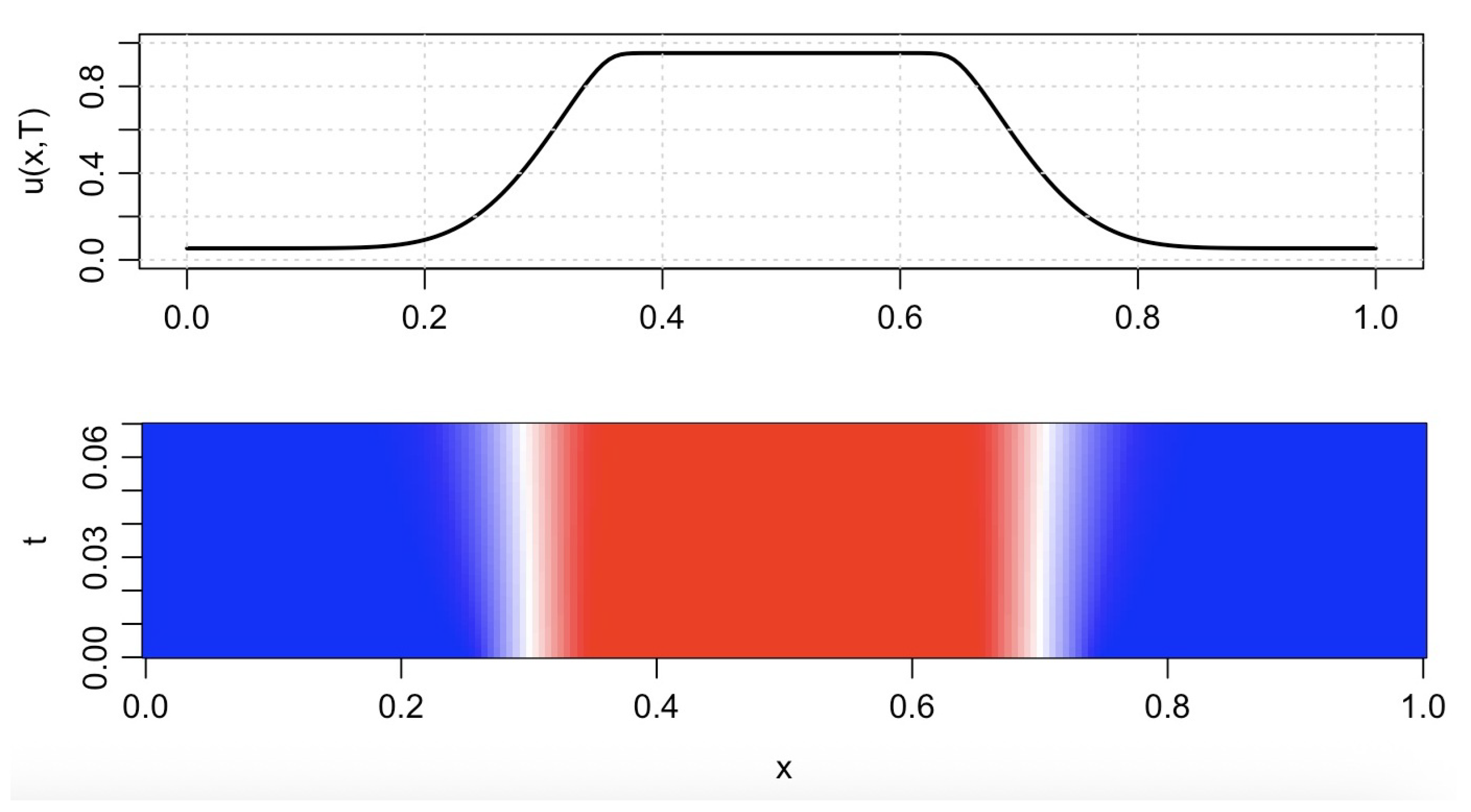

To visualise these depth-wise domains of trust and distrust,

Figure 4 shows a numerically computed long-time profile and the corresponding space–time evolution of

for the degenerate logistic–diffusion equation (

15) along the depth axis of the hierarchy.

In the top plot of

Figure 4, the final profile

is almost piecewise constant, with large intervals in which layers have converged either to

or to

. The narrow interfaces between these plateaus correspond to domain walls where the degenerate diffusion term

and the local bias

balance each other. The bottom plot shows that such profiles arise dynamically from an initially nearly homogeneous configuration: as time evolves, the local bistability of the effective potential amplifies small perturbations, nucleating domains of trust and distrust that then sharpen into plateaus and remain separated by relatively sharp fronts. In the full stochastic hierarchical model, these fronts become the natural mesoscopic objects whose motion and interactions encode large-scale reconfigurations of trust across the depth of the network.

The parameters of the model have a transparent interpretation in this phase-selection picture. The noise intensity plays the role of a “temperature of informational turbulence”: when is very small, transitions between phases are rare, domain walls are sharp and relatively immobile, and the pattern of trust and distrust is largely determined by the deterministic structure encoded in and . As increases, rare large fluctuations become more likely, enabling local patches of trust to nucleate within distrusting regions, and vice versa, and making domain walls more mobile and irregular. The effective amplification rate acts as a local “field” that biases the double–well potential towards trust or distrust at depth x: for the well at is deeper and more frequently occupied, while for negative the well at is favoured in the nearly deterministic regime. On intermediate time scales and for spatially varying , the hierarchy may therefore exhibit a transient polarised configuration in which some layers are locked in a trust phase and others in a distrust phase, separated by slowly evolving fronts.

To quantify the net outcome of this competition in the homogeneous case, we consider the long-time, depth-averaged trust level

obtained from the SPDE (

38) with constant coefficients. For each pair

we simulate the hierarchical field

over a long observation window, discard an initial transient, and compute the space–time average of

along the depth axis.

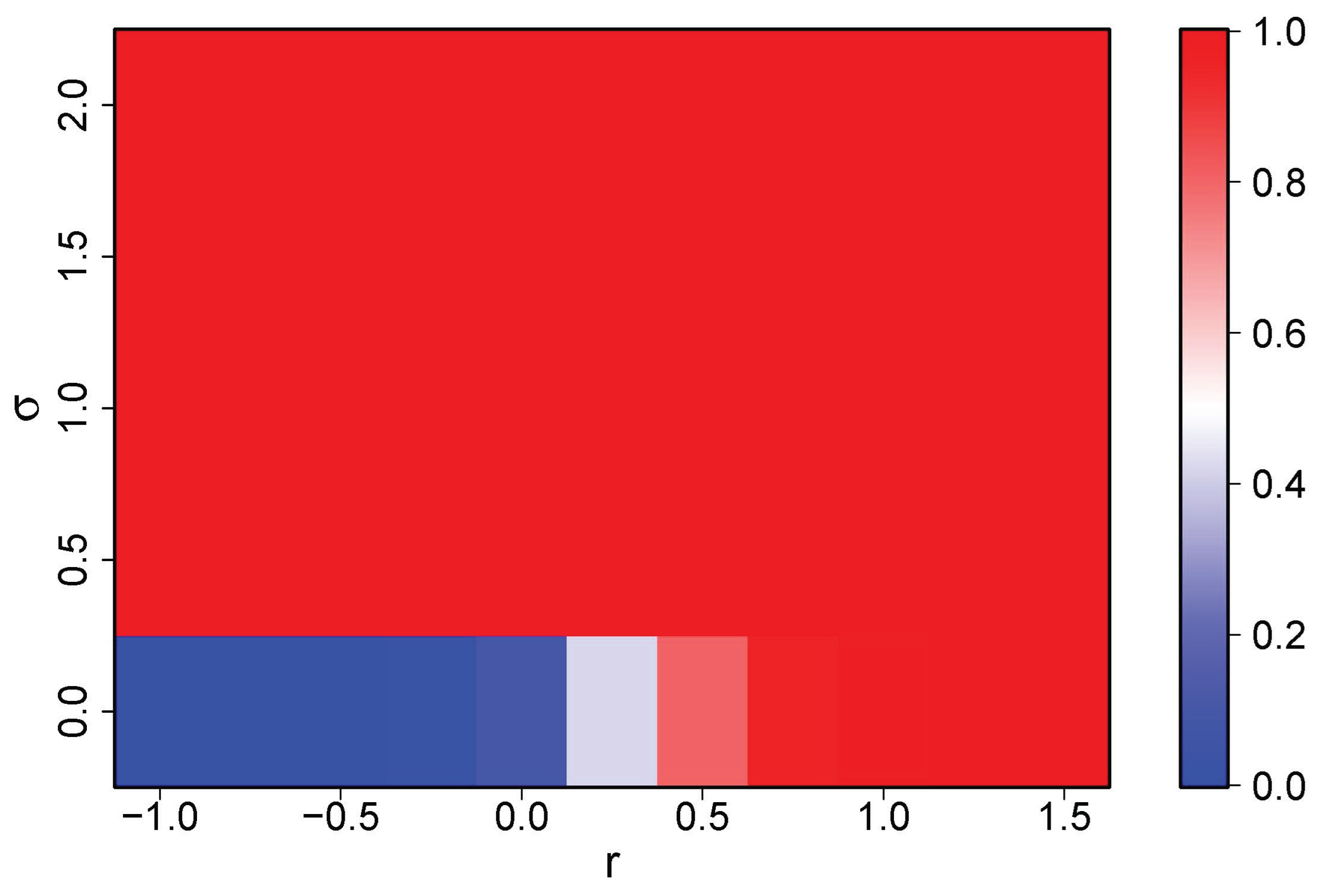

Figure 5 shows the resulting numerical phase diagram.

Figure 5 shows that, in this simple homogeneous setting, the distrust phase is only sustained when the amplification rate is negative and the informational turbulence is almost absent. As soon as

is increased to moderate values, the diagram becomes essentially saturated in red: noise-assisted escapes from the low-trust well, combined with the logistic amplification towards

, drive the hierarchy into a robust high-trust phase across the entire depth. Intermediate colours appear only in a thin low-noise band near

, reflecting parameter combinations for which the system still spends a non-negligible fraction of time in both phases. Thus the phase diagram complements the local Kramers-type switching picture [

26]: microscopic bistability at a single depth layer leads, at the macroscopic level, to either a global high-trust state or a narrow region of long-lived distrust, with only a very limited parameter window supporting persistent probabilistic coexistence of the two phases.

From a social perspective, the bistable structure of the local dynamics means that each depth layer is effectively faced with a communal choice of phase: over time, the layer either consolidates into a stable trusting disposition towards the assertion or into a stable distrusting disposition. The multiplicative noise with amplitude captures the empirical intuition that this choice is negotiated most intensely in internally divided layers, where disagreement and informational turbulence are greatest, while nearly unanimous layers are relatively inert to random perturbations. In contrast to the purely deterministic logistic model, which typically leads to a unique homogeneous attractor, the stochastic model naturally accommodates stable polarisation and metastable transitions between trust and distrust. It thereby provides a probabilistic theory of trust formation over a hierarchical backbone: long-lived trust and distrust emerge as stochastic phases of the belief field , shaped jointly by the underlying network structure and by the intensity and structure of random informational shocks.