1. Introduction

Cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE) is a severe and potentially life-threatening form of acute heart failure (AHF), caused by an abrupt rise in left atrial and pulmonary capillary pressures due to acute LV systolic and/or diastolic dysfunction or rapid intravascular volume overload [

1,

2]. Despite advances in pharmacological and device-based therapy, AHF continues to carry high short-term mortality rates and frequent readmissions [

3,

4]. Prompt risk stratification is critical to optimize early management and improve patient outcomes [

5,

6].

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is central to the initial evaluation of AHF, providing real-time information on ventricular performance, valve function, and hemodynamic status at the bedside [

7,

8]. While LVEF remains a widely used measure, it often fails to capture the hemodynamic complexity of acute decompensation, especially in presentations such as CPE [

9,

10]. Other parameters, including LV outflow tract velocity–time integral (LVOT VTI), have emerged as reliable surrogates of stroke volume and cardiac output, and have demonstrated prognostic value in both chronic and acute HF settings [

11,

12].

The prognostic relevance of RV function in CPE has historically been underappreciated, although numerous studies have demonstrated that RV dysfunction is common in AHF and independently associated with adverse outcomes [

13,

14,

15]. Simple and reproducible measurements—such as tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), tissue Doppler–derived systolic velocity of the lateral tricuspid annulus (S RV), and the RV–RA pressure gradient provide valuable insights into RV longitudinal systolic performance [

16,

17]. An imbalance between preserved RV output and impaired LV filling capacity may exacerbate pulmonary congestion, thereby contributing to the onset of CPE even when LVEF is preserved. At the acute presentation of CPE, this mismatch may result in a small but repetitive fraction of RV output not being accommodated by the LV, creating hemodynamic conditions that facilitate rapid pulmonary overfilling and alveolar flooding [

18,

19].

Given the multifactorial hemodynamic mechanisms involved, a comprehensive biventricular echocardiographic assessment at presentation could improve diagnostic accuracy and prognostic evaluation. Integrating LV and RV metrics into a combined prognostic index has been suggested to enhance outcome prediction in acute HF [

20].

In this study, we aimed to describe the clinical and echocardiographic profile of patients with CPE and to assess the comparative prognostic contribution of RV and LV dysfunction for in-hospital outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

This retrospective observational study was conducted between January 2024 and July 2025. From a registry of 222 consecutive patients hospitalized for acute heart failure (AHF), we included 28 patients who presented with cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE) as the predominant clinical phenotype.Cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE) was diagnosed based on the presence of acute respiratory distress supported by at least two of the following criteria: bilateral alveolar infiltrates on chest radiography, multiple B-lines on lung ultrasound consistent with interstitial–alveolar fluid, pulmonary auscultation revealing crackles, and arterial blood gas analysis showing hypoxemia. A rapid clinical and radiographic improvement following intravenous diuretics and/or vasodilators further supported the diagnosis [

21,

22].

From the initial group, patients with incomplete echocardiographic datasets, concomitant acute coronary syndrome, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, primary valvular emergencies, or absence of NT-proBNP measurement at admission were excluded. The final analytic cohort included 28 patients with complete echocardiographic and laboratory data suitable for comparative biventricular function analysis.

Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years, primary presentation with CPE as the dominant AHF phenotype, complete echocardiographic and laboratory evaluation within the first 24 hours of admission, including NT-proBNP measurement.

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the institutional ethics committee [

23].

2.2. Data Collection

Demographic, clinical, laboratory, and outcome data were extracted from the hospital’s electronic medical records. Clinical variables included age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, blood pressure and heart rate at presentation, and signs of congestion. Laboratory parameters included serum NT-proBNP, creatinine, hemoglobin, electrolytes, and high-sensitivity troponin [

24,

25,

26].

The in-hospital outcomes of interest were:

In-hospital mortality;

Need for respiratory support (non-invasive ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation);

Need for inotropic support;

Total duration of intensive care stay (days).

2.3. Echocardiographic Assessment

Comprehensive transthoracic echocardiography was performed within 24 hours of admission using a GE Vivid E95 ultrasound system. All measurements adhered to current ASE/EACVI recommendations [

27,

28] and were interpreted by two experienced echocardiographers blinded to patient outcomes.

Right ventricular function was assessed by:

Tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE, mm) using M-mode in the apical 4-chamber view;

Tissue Doppler–derived systolic velocity at the lateral tricuspid annulus (S RV, cm/s);

Peak systolic RV–RA pressure gradient (mmHg), derived from tricuspid regurgitation velocity using the modified Bernoulli equation [

29,

30].

Left ventricular function was assessed by:

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, %) using the biplane Simpson method;

Left ventricular outflow tract velocity–time integral (LVOT VTI, cm) measured by pulsed-wave Doppler in the apical 5-chamber view;

Tissue Doppler–derived systolic velocity at the lateral mitral annulus (S LV, cm/s) [

31,

32].

Diastolic function was characterized by:

The S LV/S RV ratio was calculated for each patient as an index of interventricular longitudinal systolic balance [

19].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), as appropriate. Group comparisons (survivors vs. non-survivors; IMV vs. no-IMV; inotrope vs. no-inotrope) were made using the independent-samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, depending on data distribution. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test [

34,

35].

Paired within-patient comparisons (e.g., S LV vs. S RV) employed the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Correlations between echocardiographic parameters and NT-proBNP, as well as with the total number of days spent in intensive care, were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for key echocardiographic parameters (TAPSE, S RV, RV-RA gradient, TAPSE/RV-RA gradient LVEF, LVOT VTI, E/E′, S LV, S LV/ S RV) to evaluate their prognostic value for in-hospital mortality and ventilatory support requirement. The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated with 95% confidence intervals using bootstrap resampling. The optimal cut-off was determined by the Youden index [

36].

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and JASP, Version 0.19 (University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), with a two-sided p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Generative artificial intelligence tools (ChatGPT, version GPT-5.1, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) were used for figure generation and minor linguistic adjustments to improve text clarity and readability.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

A total of 28 patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE) at presentation fulfilled the predefined inclusion criteria, all undergoing comprehensive echocardiographic evaluation of right and left ventricular function. Baseline demographic, clinical, and echocardiographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1.

The mean age of the study population was 73.8 ± 12.1 years, and 61.9% were male. Active smoking was reported in 21.4% of cases. Hypertension was present in all patients (100%), while dyslipidemia was highly prevalent (96.4%). Obesity was recorded in 29.6%, and diabetes mellitus in 53.6%.

At admission, the mean systolic blood pressure was 173.39 ± 38.52 mmHg and the mean diastolic blood pressure was 99.39 ± 21.23 mmHg, with a mean heart rate of 105.61 ± 23.04 bpm. The average NT-proBNP concentration was 10,514 ± 10,381 pg/mL, reflecting severe hemodynamic stress [

24,

25]. Echocardiographic measurements showed a mean TAPSE of 22.61 ± 8.20, LVOT VTI of 16.20 ± 4.52 cm, RV–RA gradient of 28.93 ± 9.74mmHg, and LVEF of 38.68 ± 15.42%. Valvular heart disease was present in 71.4 of patients.

3.2. Echocardiographic Parameters and Predictive Analysis for In-Hospital Mortality

Four patients (14.3%) died during hospitalization. Comparative analysis of echocardiographic parameters between survivors (n = 24) and non-survivors (n = 4) is presented in

Table 2. While none of the parameters reached statistical significance, several clinically relevant trends were observed.

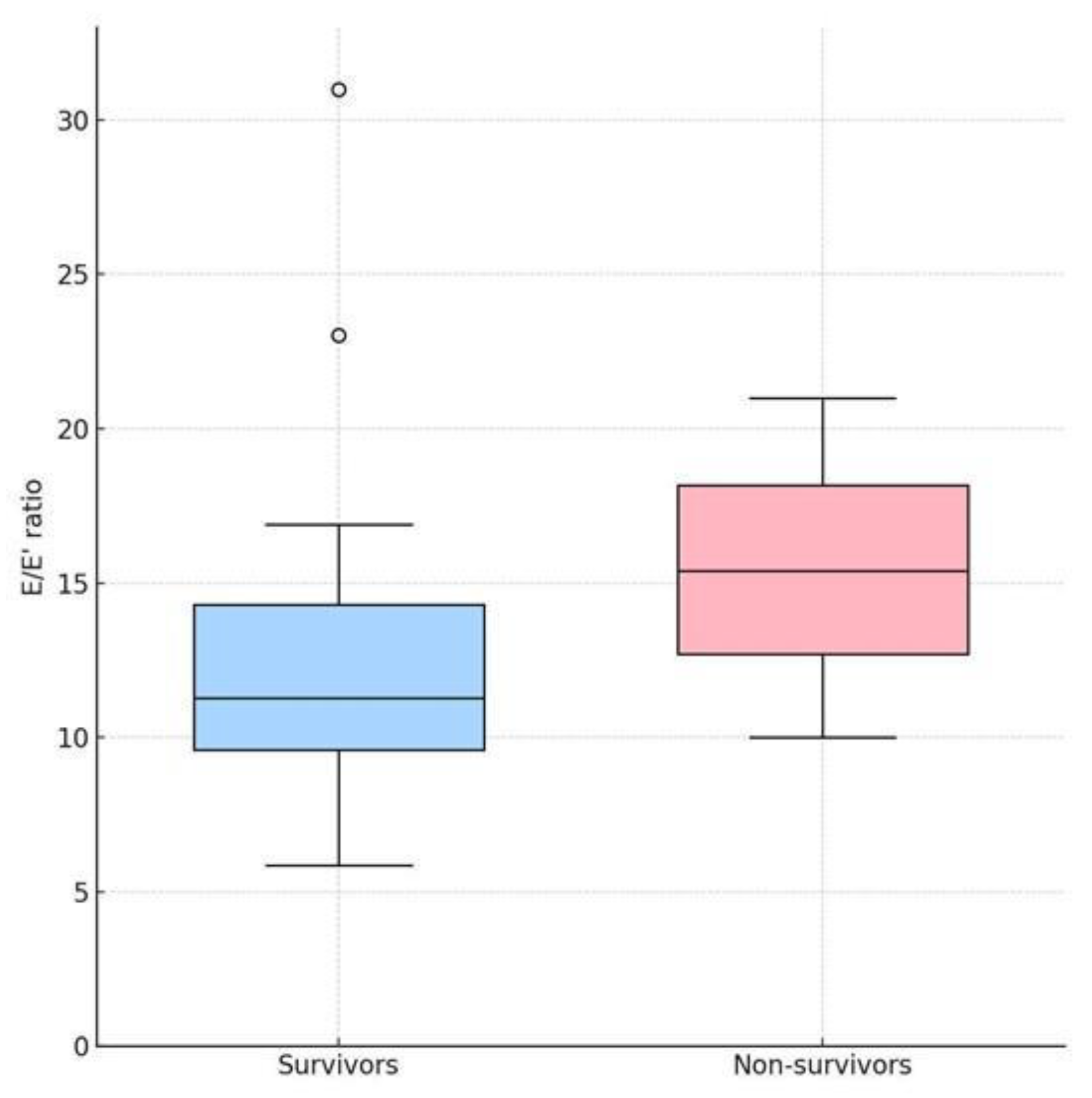

The E/E′ ratio, a surrogate of LV filling pressures, was higher in non-survivors compared to survivors (median: 15.4 vs. 11.3; p = 0.291), suggesting that elevated diastolic pressures may be associated with worse prognosis [

33,

37]. This distribution is illustrated in

Figure 1, where the median E/E′ is visibly higher in the non-survivor group, though with overlapping interquartile ranges.

TAPSE and S RV, markers of RV longitudinal systolic function, tended to be lower in non-survivors (TAPSE: 19.0 vs. 20.0 mm, p = 0.323; S RV: 10.0 vs. 12.0 cm/s, p = 0.339), indicating possible RV impairment in patients with fatal outcomes [

13,

15]. S LV was slightly lower in non-survivors (6.75 vs. 6.90 cm/s; p = 0.669), reflecting mild LV longitudinal systolic impairment across the cohort. The S LV/S RV ratio was marginally higher in non-survivors (0.73 vs. 0.61; p = 0.533).

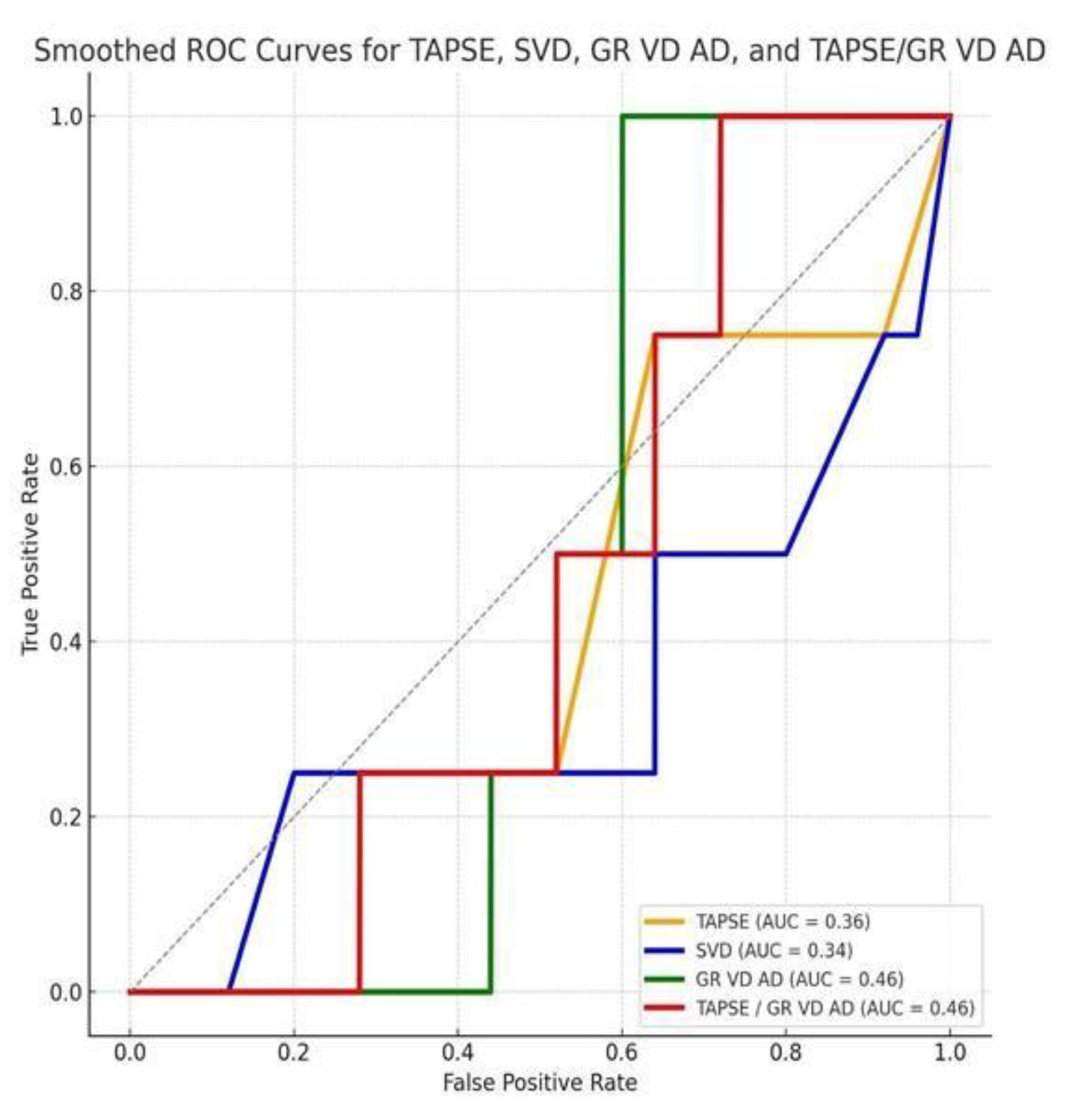

ROC curve analysis was therefore performed for key RV parameters (

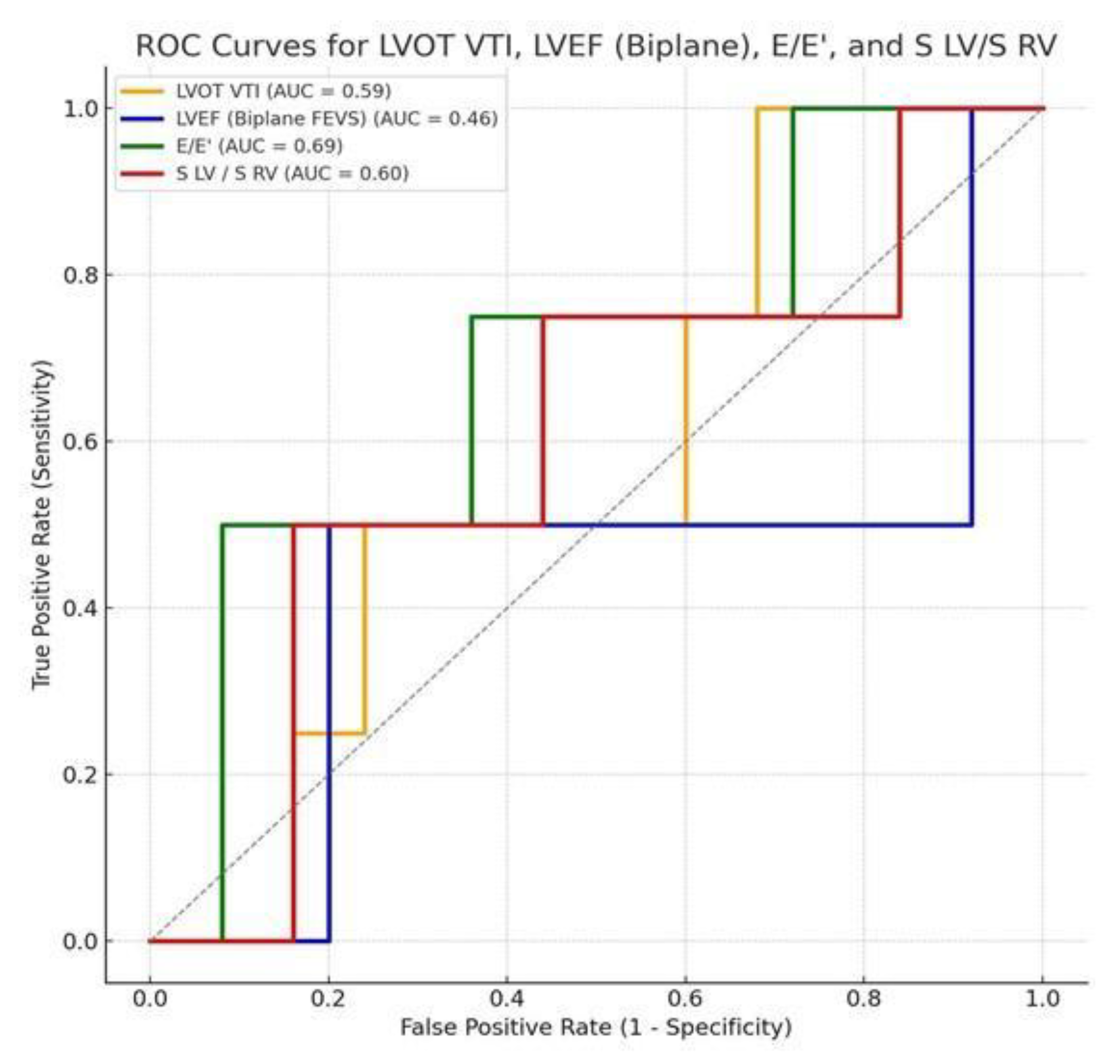

Figure 2), LV parameters and S LV/S RV ratio (

Figure 3).

Figure 2 displays ROC curves for TAPSE, S RV, the RV–RA gradient, and the TAPSE/RV–RA gradient ratio; all showed only modest discriminative performance, with curves clustering near the diagonal and no single RV metric clearly outperforming the others.

Figure 3 depicts the ROC curves for LVOT VTI, LVEF, E/E′, and the S′ LV/S′ RV ratio. Among the evaluated parameters, the E/E′ ratio demonstrated the highest discriminatory performance (AUC = 0.69), although this did not reach statistical significance. The S′ LV/S′ RV ratio showed moderate discrimination (AUC = 0.60), with an optimal threshold of 0.83 according to Youden’s index. LVOT VTI yielded an AUC of 0.59, with an exploratory cut-off value of 13.9 cm (p = 0.47), consistent with previously reported prognostic ranges (<14–17 cm) [

11,

12]. In contrast, LVEF exhibited limited discriminatory ability.

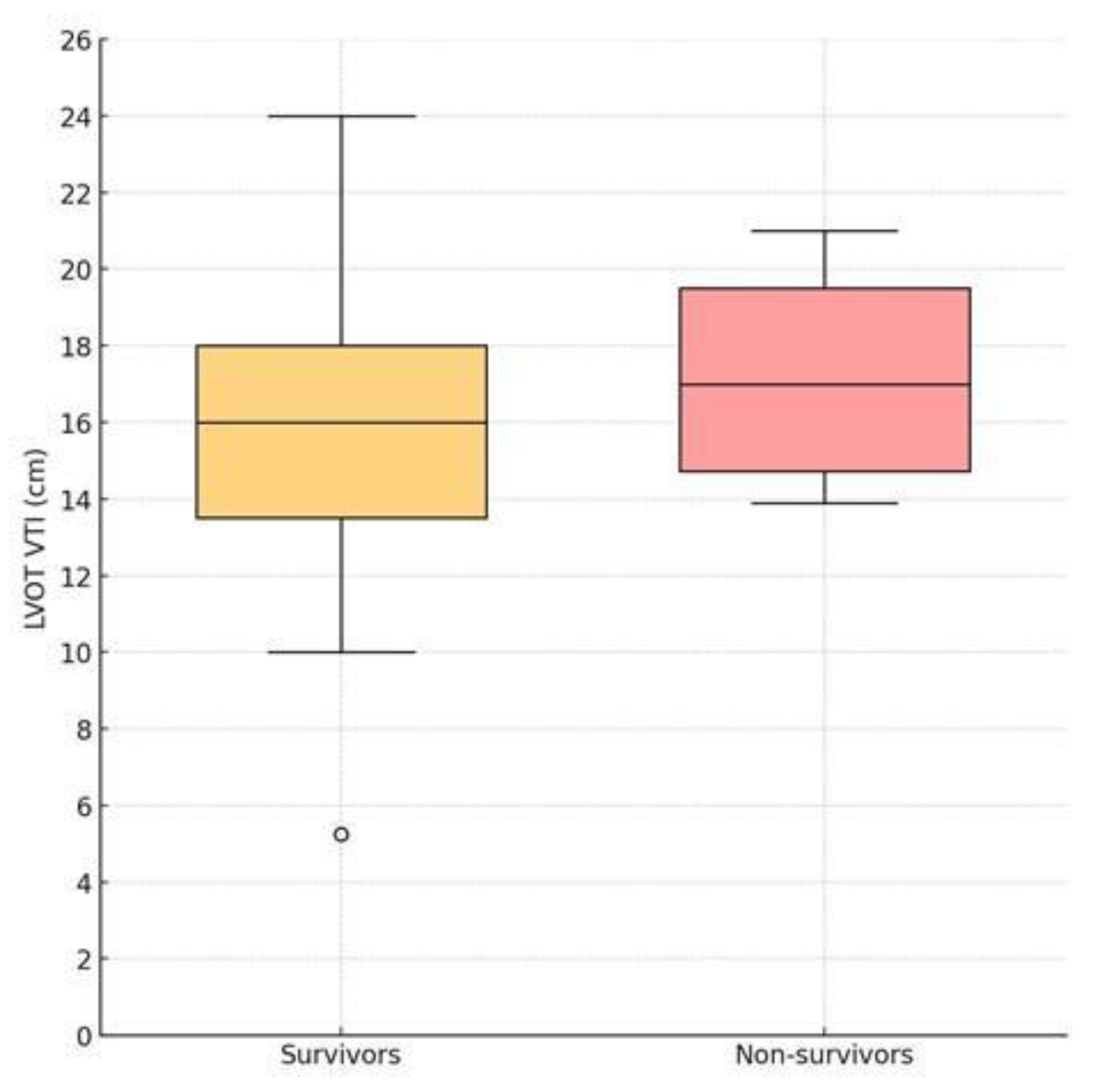

Contrary to our a priori hypothesis, LVOT VTI was not lower in non-survivors: median 17.0 cm (IQR 14.7–19.5) vs. 16.0 cm (13.4–18.3) in survivors (p = 0.645). The ROC-derived cut-off of 13.9 cm showed limited discrimination in this cohort. However, prior data suggest that LVOT VTI < 17 cm is associated with low cardiac output and poor outcomes in acute heart failure [

11,

12].

To further illustrate the distribution of left ventricular outflow tract velocity–time integral (LVOT VTI) according to in-hospital survival status, we performed a boxplot-based comparative analysis between survivors and non-survivors (

Figure 4).

None of the evaluated ROC curves reached statistical significance, and all results should therefore be interpreted as exploratory given the limited sample size.

3.4. Ventilation and Intensive Care Requirements

In the analyzed cohort, 7 patients (25%) required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), while 11 patients (39.3%) underwent at least one episode of non-invasive ventilation (NIV/CPAP). The median duration of cardiac intensive care unit stay was 4 days (IQR: 2–6), with a range from 0 to 33 days. To evaluate the association between ventricular function and the need for invasive ventilation, we compared echocardiographic parameters between patients with and without IMV (

Table 3). Although no parameter reached statistical significance, S RV showed the lowest p-value, suggesting a trend toward more pronounced right ventricular systolic impairment in ventilated patients. However, when interpreted alongside the concomitant reduction in LVEF, these findings indicate a tendency toward predominantly right-sided dysfunction within an overall context of biventricular systolic involvement in patients who required invasive ventilatory support.

Spearman correlation analysis showed no statistically significant associations between echocardiographic parameters and ICU length of stay. However, S LV and E/E’ displayed the lowest p-values, suggesting a non-significant trend whereby patients with lower LV systolic velocities and higher filling pressures tended to remain longer in the ICU. A similar, albeit weaker, tendency was observed for LVEF and TAPSE, consistent with more advanced biventricular dysfunction in patients requiring prolonged intensive care, as shown in

Table 4.

From a clinical perspective, these exploratory findings suggest that subtle alterations in LV diastolic filling (reflected by higher E/E’ ratio) and biventricular systolic impairment could contribute to the complexity of acute management in CPE, potentially prolonging intensive care needs. Although not statistically significant in this limited cohort, the observed patterns are pathophysiologically plausible and highlight the value of integrated biventricular and diastolic assessment in predicting the intensity of care required [

12,

22].

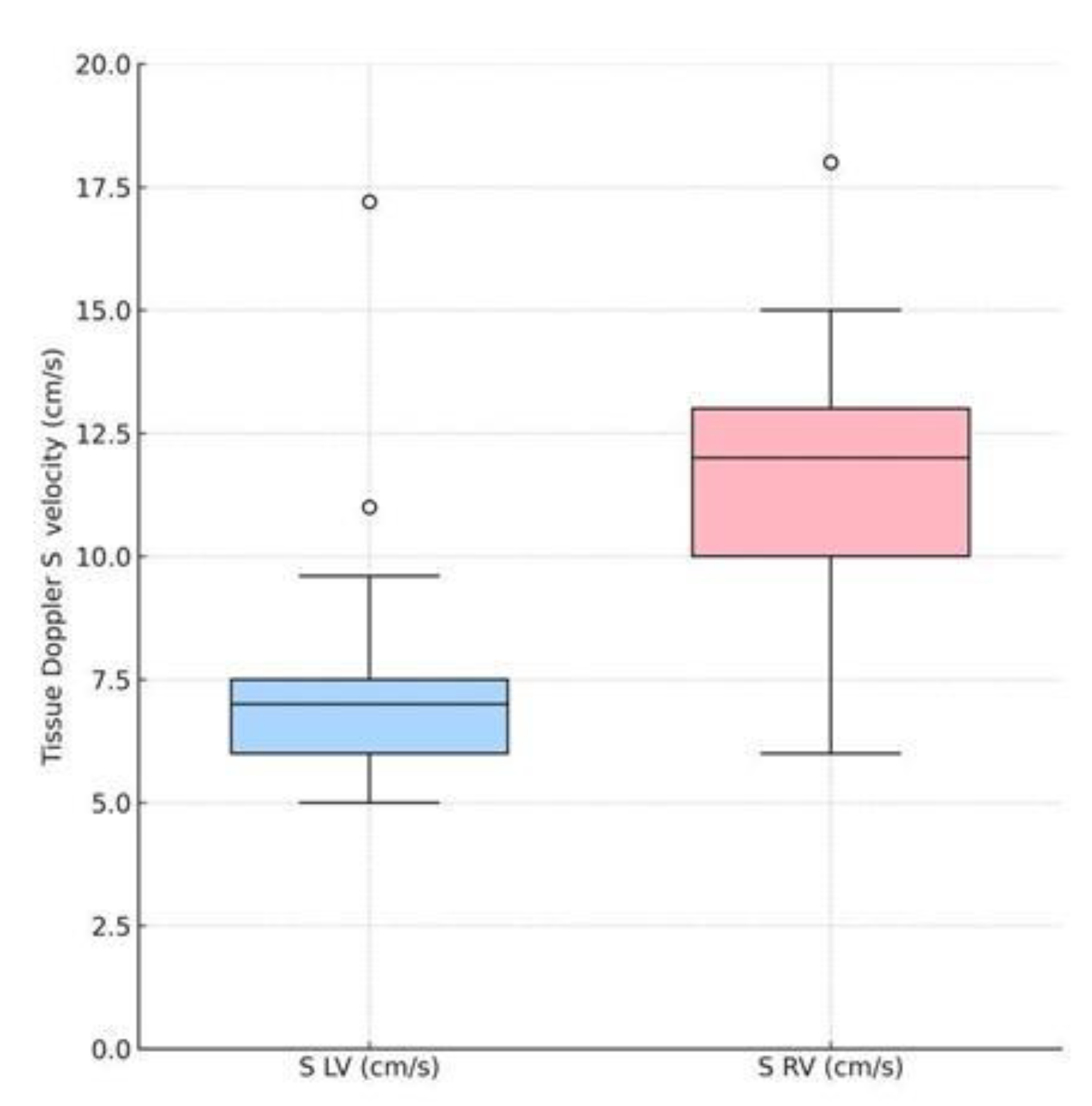

3.5. Comparative Analysis of S LV and S RV

To explore potential differences in longitudinal systolic performance between the left and right ventricles in patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE), we compared the tissue Doppler–derived systolic velocity of the lateral mitral annulus (S LV) with that of the lateral tricuspid annulus (S RV). This analysis included all 28 patients with complete data for both parameters.

The mean S LV was 7.34 ± 2.38 cm/s, significantly lower than the mean S RV of 11.49 ± 2.70 cm/s (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p < 0.001), indicating a substantial imbalance in longitudinal systolic velocities favoring the right ventricle [

18].

Figure 5 shows the paired distribution of S LV and S RV values, with the median S RV clearly exceeding S LV, highlighting predominant left ventricular longitudinal systolic impairment.

Interpretation:

The significantly lower S LV compared to S RV suggests that, at presentation, left ventricular longitudinal systolic function is more compromised than right ventricular function in this CPE population. This finding aligns with the pathophysiological model in which acute increases in left atrial and pulmonary venous pressures—secondary to LV diastolic and/or systolic dysfunction—are primary drivers of pulmonary edema.

Preserved or relatively higher S RV values may indicate maintained RV longitudinal performance in the acute phase, allowing the right ventricle to sustain forward flow into the pulmonary circulation. This could exacerbate the transcapillary pressure gradient across the pulmonary microvasculature when LV filling pressures are elevated, thereby contributing to alveolar flooding.

These results complement the descriptive and exploratory analyses presented in previous sections, suggesting that ventricular systolic imbalance—particularly when LV longitudinal contraction is disproportionately reduced compared to RV—may be a relevant hemodynamic profile in acute CPE. Further studies with larger cohorts are warranted to assess whether the degree of S LV to S RV disparity has independent prognostic implications.

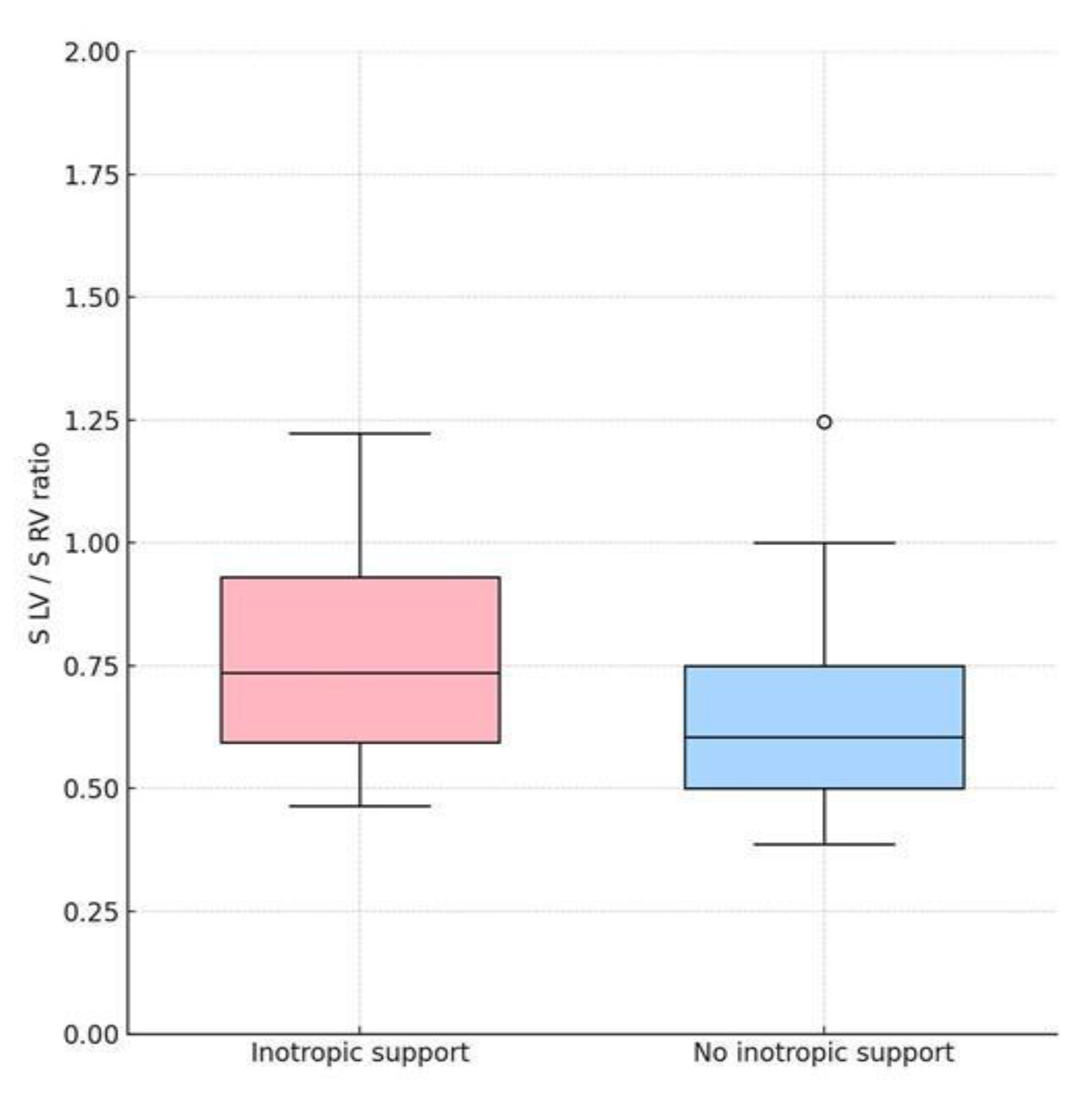

3.6. Association between Echocardiographic Parameters and Inotropic Support

In the study cohort, 7 patients (24.1%) required inotropic support during hospitalization. Comparative analysis of key echocardiographic markers of right and left ventricular function between patients with and without inotropic therapy is shown in

Table 5.

No statistically significant differences were observed for any of the measured parameters. However, a trend toward higher S LV/S RV ratio was noted among patients requiring inotropes as shown in

Figure 6 (p = 0.393). LVEF also showed slightly lower values in the inotrope group, but without statistical significance (p = 0.449).

These findings suggest that in this small cohort, the need for inotropic therapy was not clearly associated with any single echocardiographic measure of systolic function. The observed trends could indicate that subtle RV systolic impairment or interventricular systolic imbalance might be related to hemodynamic instability requiring pharmacologic support, but larger sample sizes are needed to validate this hypothesis [

17,

30].

4. Discussion

This study investigated the comparative systolic function of the left and right ventricles in patients presenting with cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE), using tissue Doppler–derived systolic velocities (S LV and S RV), conventional echocardiographic indices (TAPSE, LVEF, LVOT VTI, E/E′), and selected outcome measures, including in-hospital mortality, need for ventilatory and inotropic support, and intensive care stay.

Our main findings are:

Left ventricular longitudinal systolic function (S LV) was significantly lower than right ventricular function (S RV) at presentation, indicating predominant LV systolic impairment in the longitudinal axis despite preserved RV velocities.

No echocardiographic parameter demonstrated strong discriminatory power for in-hospital mortality. E/E′ ratio demonstrated the highest discriminatory performance (AUC = 0.69), but without statistical significance.Contrary to our initial hypothesis, LVOT VTI was not lower in non-survivors, but the ROC-derived cut-off of 13.9 cm overlapped with values previously reported as prognostically relevant in acute heart failure cohorts [

12,

20].

No echocardiographic parameter was significantly associated with the need for invasive ventilation or inotropic support, but exploratory analysis suggested trends toward lower RV systolic velocities and altered interventricular balance in patients requiring hemodynamic support.

Regarding intensive care stay, none of the echocardiographic indices correlated significantly with its duration. However, patients with higher mitral E velocity and reduced S LV tended to require longer intensive care hospitalization, suggesting that impaired LV filling and systolic imbalance may contribute to more complex trajectories [

33,

37].

4.1. Comparison with Previous Studies

Previous work has emphasized the central role of elevated LV filling pressures in the pathophysiology of CPE, often in the setting of preserved or mildly reduced LVEF [

1,

2]. Our finding of markedly reduced S LV compared to S RV complements this understanding by demonstrating a measurable imbalance in longitudinal systolic velocities between ventricles at the acute phase.

Studies in acute heart failure populations have shown that tissue Doppler velocities, particularly S RV, are independent predictors of outcome, reflecting RV–pulmonary artery coupling [

13,

15]. In our cohort, S RV was relatively preserved, possibly allowing sustained pulmonary forward flow and contributing to rapid alveolar flooding when LV compliance and systolic performance are impaired.

The ROC-derived LVOT VTI cut-off of 13.9 cm identified in our analysis is consistent with previous reports linking low stroke volume to poor prognosis [

11,

12]. The paradoxical observation that non-survivors exhibited slightly higher median VTI than survivors is most likely explained by small sample size and Doppler variability, but it does not negate the alignment of the cut-off with prior literature. Similarly, the S LV/S RV ratio, although not statistically significant, suggested a tendency toward worse outcomes when interventricular systolic imbalance was present [

20].

4.2. Clinical Implications

From a hemodynamic perspective, the observed ventricular imbalance supports the hypothesis that RV–LV stroke volume mismatch may be an important driver of acute decompensation in CPE, particularly in hypertensive presentations [

18,

19]. Tissue Doppler–derived systolic velocities are simple to obtain in the emergency setting and may help identify patients with disproportionate LV impairment despite preserved RV performance.

Although no single parameter showed robust predictive power in this dataset, the combined assessment of LV and RV systolic velocities, LVOT VTI, and diastolic filling pressures could contribute to a rapid, non-invasive evaluation framework for CPE patients. Such an approach might assist in early identification of individuals who could benefit from intensified hemodynamic monitoring, tailored diuretic–vasodilator strategies, or early escalation to advanced therapies.

4.3. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it is retrospective and single-center, with a small sample size, limiting the statistical power to detect significant associations. Second, echocardiographic measurements were performed at a single time point, without serial follow-up to capture dynamic changes during hospitalization. Third, invasive hemodynamic data were not available to corroborate echocardiographic findings. Finally, the exclusion of patients with incomplete datasets, while necessary for analytic consistency, may have introduced selection bias.

4.4. Future Directions

Prospective multicenter studies with larger patient populations are needed to validate the prognostic value of interventricular systolic imbalance in CPE. Incorporating advanced imaging techniques such as speckle-tracking strain, pulmonary artery coupling indices, and validated integrated measures like the cardiac power index could enhance risk stratification [

22,

29].

Furthermore, integrating echocardiographic parameters with biomarkers (e.g., NT-proBNP) and clinical profiles into multiparametric predictive models may improve early risk stratification and guide individualized therapeutic interventions. Comparative validation of such models against established indices would clarify the incremental prognostic utility of biventricular functional assessment in this high-risk population.

5. Conclusions

In this study of patients presenting with cardiogenic pulmonary edema (CPE), we identified a marked imbalance between left and right ventricular longitudinal systolic performance, with significantly lower S LV compared to S RV at presentation. This observation supports the concept that left ventricular dysfunction , particularly in the longitudinal axis, is a key driver of pulmonary edema, even when right ventricular function remains relatively preserved [

38].

Although no single echocardiographic parameter demonstrated strong independent prognostic power in this limited cohort, several clinically relevant trends emerged. Reduced LVOT VTI, altered S LV/S RV ratios, and lower S RV values were associated with adverse outcomes, including mortality and the need for inotropic support, consistent with previous studies linking impaired forward flow and biventricular imbalance to poor prognosis in acute heart failure [

11]. Trends toward longer intensive care stays were observed in patients with higher mitral E velocity and reduced S LV, suggesting that impaired LV filling and interventricular imbalance may contribute to more severe clinical trajectories [

33,

38].

These findings reinforce the importance of comprehensive biventricular assessment in patients with CPE, moving beyond conventional reliance on LVEF. The observed patterns align with the conceptual framework of multiparametric indices, such as the Virtue Index, which integrate LV systolic, RV systolic, and diastolic markers to improve risk stratification [

20].

While limited by its retrospective, single-center design and small sample size, this study underscores the potential role of combined echocardiographic assessment in guiding clinical decision-making for patients with CPE. Prospective multicenter trials incorporating advanced imaging, biomarkers, and integrated prognostic indices are warranted to validate these findings and to refine early risk stratification strategies [

37].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Popescu Dan and Diana Țînț; Data curation, Popescu Dan; Formal analysis, Popescu Dan; Investigation, Popescu Dan and Nechita Alexandru; Methodology, Popescu Dan and Ciobanu Mara; Supervision, Diana Țînț; Writing – original draft, Popescu Dan; Writing – review & editing, Ciobanu Mara, Diana Țînț and Nechita Alexandru.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As stated in the Methods section, the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Emergency Clinical Hospital “Sf. Pantelimon”, Bucharest (Approval No. 77 / 09.09.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to patient privacy and confidentiality restrictions.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (version GPT-5.1, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) to assist in generating visual representations of data (graphs). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC |

area under the curve |

| BP |

blood pressure |

| bpm |

beats per minute |

| CPE |

cardiogenic pulmonary edema |

| CW |

continuous wave |

| E-wave (E) |

peak early mitral inflow velocity |

| E/E′ |

ratio of early mitral inflow velocity to early diastolic mitral annular velocity |

| ICU |

intensive care unit |

| IMV |

invasive mechanical ventilation |

| IQR |

interquartile range |

| IVC |

inferior vena cava |

LV

LVEF |

left ventricle

left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LVOT |

left ventricular outflow tract |

| LVOT VTI |

left ventricular outflow tract velocity–time integral |

| NIV |

non-invasive ventilation |

| NT-proBNP |

N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide |

| PW |

pulsed wave |

| ROC |

receiver operating characteristic |

RV

RV-RA gradient |

right ventricle

right ventricle–right atrium systolic pressure gradient |

| S LV |

systolic velocity of the lateral mitral annulus |

| S RV |

systolic velocity of the lateral tricuspid annulus |

| TAPSE |

tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion |

References

- Gandhi, SK; Powers, JC; Nomeir, AM; Fowle, K; Kitzman, DW; Rankin, KM; Little, WC. The pathogenesis of acute pulmonary edema associated with hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344(1), 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiade, M; De Luca, L; Fonarow, GC; Filippatos, G; Metra, M; Francis, GS. Pathophysiologic targets in the early phase of acute heart failure syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2005, 96(6A), 11G–17G. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chioncel, O; Lainscak, M; Seferovic, PM; Anker, SD; Crespo-Leiro, MG; Harjola, VP; et al. Epidemiology and one-year outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction: an analysis of the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017, 19(12), 1574–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosy, AP; Fonarow, GC; Butler, J; Chioncel, O; Greene, SJ; Vaduganathan, M; et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014, 63(12), 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, SP; Lindsell, CJ; Jenkins, CA; Harrell, FE; Fermann, GJ; Miller, KF; et al. Risk stratification in acute heart failure: rationale and design of the STRATIFY and DECIDE studies. Am Heart J. 2012, 164(6), 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harjola, VP; Mebazaa, A; Čelutkienė, J; Bettex, D; Bueno, H; Chioncel, O; et al. Contemporary management of acute right ventricular failure: a statement from the Heart Failure Association and the Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016, 18(3), 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, RM; Bierig, M; Devereux, RB; Flachskampf, FA; Foster, E; Pellikka, PA. American Society of Echocardiography’s Nomenclature and Standards Committee; Task Force on Chamber Quantification; American College of Cardiology Echocardiography Committee; American Heart Association; European Association of Echocardiography, European Society of Cardiology. Recommendations for chamber quantification. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006, 7(2), 79–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, SF; Smiseth, OA; Appleton, CP; Byrd, BF, 3rd; Dokainish, H; Edvardsen, T; et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016, 29(4), 277–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, SJ; Katz, DH; Deo, RC. Phenotypic spectrum of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Clin Epub. 2014, 10(3), 407–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ponikowski, P; Voors, AA; Anker, SD; Bueno, H; Cleland, JGF; Coats, AJS; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016, 37(27), 2129–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C; Rubenson, D; Srivastava, A; Mohan, R; Smith, MR; Billick, K; et al. Left ventricular outflow tract velocity time integral outperforms ejection fraction and Doppler-derived cardiac output for predicting outcomes in a select advanced heart failure cohort. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2017, 15(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez, J; Mainar, L; Bodí, V; Sanchis, J; Núñez, E; Miñana, G; et al. Valor pronóstico de la fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo en pacientes con insuficiencia cardíaca aguda [Prognostic value of the left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with acute heart failure]. Med Clin (Barc) 2008, 131(5), 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F; Doyle, R; Murphy, DJ; Hunt, SA. Right ventricular function in cardiovascular disease, part II: pathophysiology, clinical importance, and management of right ventricular failure. Circulation 2008, 117(13), 1717–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzano, A; D’Assante, R; Iacoviello, M; Triggiani, V; Rengo, G; Cacciatore, F; Maiello, C; Limongelli, G; Masarone, D; Sciacqua, A; Filardi, PP; Mancini, A; Volterrani, M; Vriz, O; Castello, R; Passantino, A; Campo, M; Modesti, PA; De Giorgi, A; Arcopinto, M; Gargiulo, P; Perticone, M; Colao, A; Milano, S; Garavaglia, A; Napoli, R; Suzuki, T; Bossone, E; Marra, AM; Cittadini, A. T.O.S.CA. Investigators. Progressive right ventricular dysfunction and exercise impairment in patients with heart failure and diabetes mellitus: insights from the T.O.S.CA. Registry. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022, 21(1), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zimbarra Cabrita, I; Ruisanchez, C; Dawson, D; Grapsa, J; North, B; Howard, LS; Pinto, FJ; Nihoyannopoulos, P; Gibbs, JS. Right ventricular function in patients with pulmonary hypertension; the value of myocardial performance index measured by tissue Doppler imaging. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2010, 11(8), 719–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edward, J; Banchs, J; Parker, H; Cornwell, W. Right ventricular function across the spectrum of health and disease. Heart 2023, 109(5), 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, N; Rajagopalan, N; Edelman, K; López-Candales, A. Tricuspid annular systolic velocity: a useful measurement in determining right ventricular systolic function regardless of pulmonary artery pressures. Echocardiography 2006, 23(9), 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, KL; Dabiri, Y; Franz, T; Solomon, SD; Burkhoff, D; Guccione, JM. Investigating the role of interventricular interdependence in development of right heart dysfunction during LVAD support: a patient-specific methods-based approach. Front Physiol. 2018, 9, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donker, DW; Sallisalmi, M; Broomé, M. Right-left ventricular interaction in left-sided heart failure with and without venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: a simulation study. ASAIO J 2021, 67(3), 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, DC; Ciobanu, M; Țînț, D; Nechita, AC. Linking Heart Function to Prognosis: The Role of a Novel Echocardiographic Index and NT-proBNP in Acute Heart Failure. Medicina 2025, 61, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ural, D; Çavuşoğlu, Y; Eren, M; Karaüzüm, K; Temizhan, A; Yılmaz, MB; et al. Diagnosis and management of acute heart failure. Anatol J Cardiol. 2015, 15(11), 860–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, G; Moshkovitz, Y; Kaluski, E; Milo, O; Nobikov, Y; Schneeweiss, A; et al. The role of cardiac power and systemic vascular resistance in the pathophysiology and diagnosis of patients with acute congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003, 5(4), 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310(20), 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, PA; Nowak, RM; McCord, J; Hollander, JE; Herrmann, HC; Steg, PG; et al. B-type natriuretic peptide and clinical judgment in emergency diagnosis of heart failure: analysis from Breathing Not Properly (BNP) Multinational Study. Circulation 2002, 106(4), 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisel, AS; Krishnaswamy, P; Nowak, RM; McCord, J; Hollander, JE; Duc, P. Breathing Not Properly Multinational Study Investigators. Rapid measurement of B-type natriuretic peptide in the emergency diagnosis of heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002, 347(3), 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Januzzi, JL, Jr.; Camargo, CA; Anwaruddin, S; Baggish, AL; Chen, AA; Krauser, DG; et al. The N-terminal pro-BNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am J Cardiol. 2005, 95(8), 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, RM; Badano, LP; Mor-Avi, V; Afilalo, J; Armstrong, A; Ernande, L; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015, 16(3), 233–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C; Rahko, PS; Blauwet, LA; Canaday, B; Finstuen, JA; Foster, MC; et al. Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiographic examination in adults: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019, 32(1), 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudski, LG; Lai, WW; Afilalo, J; Hua, L; Handschumacher, MD; Chandrasekaran, K; et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010, 23(7), 685–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, VC; Takeuchi, M. Echocardiographic assessment of right ventricular systolic function. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2018, 8(1), 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, NP; Loh, PH; Silva, Rd; Ghosh, J; Khaleva, OY; Goode, K; et al. Prognostic value of systolic mitral annular velocity measured with Doppler tissue imaging in patients with chronic heart failure caused by left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Heart 2006, 92(6), 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M; Yip, GW; Wang, AY; Zhang, Y; Ho, PY; Tse, MK; et al. Tissue Doppler imaging provides incremental prognostic value in patients with systemic hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. J Hypertens. 2005, 23(1), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagueh, SF; Middleton, KJ; Kopelen, HA; Zoghbi, WA; Quiñones, MA. Doppler tissue imaging: a noninvasive technique for evaluation of left ventricular relaxation and estimation of filling pressures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997, 30(6), 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, TK. T test as a parametric statistic. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2015, 68(6), 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, JH. Handbook of Biological Statistics, 3rd ed.; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Youden, WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950, 3(1), 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J; de la Espriella, R; Rossignol, P; Voors, AA; Mullens, W; Metra, M; et al. Congestion in heart failure: a circulating biomarker-based perspective. A review from the Biomarkers Working Group of the Heart Failure Association, European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2022, 24(10), 1751–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okura, H; Kubo, T; Asawa, K; Toda, I; Yoshiyama, M; Yoshikawa, J; Yoshida, K. Elevated E/E′ predicts prognosis in congestive heart failure patients with preserved systolic function. Circ J 2009, 73(1), 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).