1. Introduction

Metaplasticity is the dynamic ability of the brain to manage the degree and direction of synaptic plasticity in response to past neuronal activity. Often referred to asthe “plasticity of synaptic plasticity” [

1], it is a process of a higher order that manages the brain’s learning and memory capability by maintaining neural circuits within an optimal range of responsiveness. This mechanism is thought to place homeostatic control over long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP), preventing runaway depression or excitation and allowing adaptive flexibility in terms of changing environmental or internal states [

2].

Metaplasticity has been thoroughly explored in preclinical cellular and molecular studies, particularly in hippocampal and cortical slice preparation. However, its relevance to human brain function, and specifically to the modulation of cognition via non-invasive brain stimulation, has been less explored, despite the fact that there is emerging evidence that suggests that the effectiveness of interventions such as tDCS and tACS depends on the brain’s baseline activity state and previous stimulation history, which are consistent with metaplasticity mechanisms [

3,

4].

Cantone et al. [

3] have operationalized metaplasticity as state-dependent modulation of synaptic plasticity that emphasizes its state-dependent and adaptive nature. Two properties are the characteristics of this phenomenon: 1. priming, where previous neural activation enforces a novel physiological condition that affects subsequent plastic change, and 2. state-dependent responsiveness, where synaptic plasticity is either enhanced or reduced depending on this previous activity. Combined, the two mechanisms act as a homeostatic gain-control system, enabling flexible but stable neuroplastic adaptation.

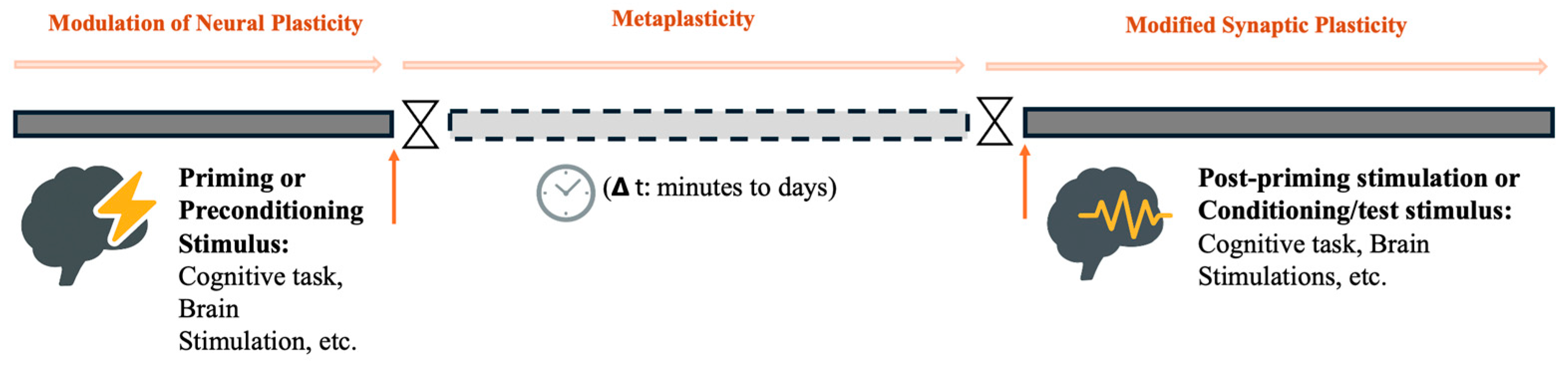

Figure 1.

Illustration of metaplasticity as a time-dependent modulation of synaptic plasticity. The diagram highlights the temporal gap (Δt), potential expression (homo- or heterosynaptic), and function (homeostatic or non-homeostatic) of the plastic changes.

Figure 1.

Illustration of metaplasticity as a time-dependent modulation of synaptic plasticity. The diagram highlights the temporal gap (Δt), potential expression (homo- or heterosynaptic), and function (homeostatic or non-homeostatic) of the plastic changes.

There is growing interest in the involvement of metaplasticity in cognition, particularly in non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques such as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), and transcranial random noise stimulation (tRNS). These techniques entail the use of weak electrical currents on the scalp to alter the excitability of neurons and synaptic efficacy in certain cortical regions and are widely employed both in cognitive improvement and clinical rehabilitation.

tDCS is among the most extensively researched non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) methods. It involves sending a steady, low-intensity current, usually 1–2 mA, between two electrodes that are placed on the scalp. Anodal tDCS tends to cause depolarization, which makes the cortex more excitable, while cathodal tDCS causes hyperpolarization and makes the cortex less excitable [

5]. These phenomena occur both during and after stimulation and are believed to underlie improvements in cognitive domains such as working memory and attention [

6,

7]. The waveform is defined by a steady current offset from zero, with a polarity-dependent direction.

Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), by contrast, delivers oscillating sinusoidal currents whose frequency and phase can be precisely controlled. These parameters allow tACS to entrain endogenous brain oscillations by causing neural synchrony and resonance, particularly when stimulation is phase-locked with cognitive task timing. Frequencies are selected that are associated with specific neural oscillatory bands (e.g., theta with memory, alpha with attention), enabling individualized modulation of network function [

8]. The effect of tACS, especially at higher frequencies (>100 Hz), can influence cortical excitability as well as native oscillation power and phase, effects measurable during and after stimulation [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The waveform consists of a smooth sine wave alternating symmetrically between positive and negative polarities.

tRNS delivers an alternating current that quickly switches among randomly changing amplitudes and frequencies across a broad spectral band, say between 0.1 Hz and 640 Hz. This stimulation is believed to enhance cortical excitability because of stochastic resonance, a mechanism through which randomly added electrical noise enhances weak or subthreshold neural signals and therefore the probability of neuron firing. tRNS has been shown to have promise in facilitating perceptual learning, neuroplastic adaptation, and cognitive performance, particularly in conjunction with the performance of a task or multiple repeated training procedures [

13,

14,

15]. The waveform resembles a fluctuating, noise-like signal symmetrically distributed around zero current.

While each of the three modalities holds promise for cognitive function enhancement, such as memory, attention, and executive control, outcomes across studies have been highly variable. Recent evidence indicates that variability may occur, at least in part, due to insufficient integration of metaplasticity principles, the history-dependent adaptation of synaptic plasticity [

16]. The effects of prior brain activity, baseline excitability, task performance, stimulation order, and inter-session timing can have profoundly different directions and magnitudes of plastic changes. Thus, stimulation effects are not homogeneous or additive; the same protocol can facilitate, suppress, or have no effect at all depending on the context of the neurons [

17,

18].

tRNS consists of a continuously fluctuating current with randomized frequencies and amplitudes within a defined intensity range. All waveforms are illustrated within a ±1 mA range for comparison.

As heterogeneity and complexity of tES protocols continue to increase, as well as the suggested key contribution of metaplasticity in modulating cognitive impact, evidence needs to be accumulated to identify patterns underlying successful stimulation design. Hence, the aim of this current systematic review is to explore the effect of protocol-specific characteristics of tDCS, tRNS, and tACS on metaplasticity-induced modulation of cognition. This review will critically examine the impact of priming paradigms, stimulation intensity, timing, and electrode montage on cognitive processes, including memory, attention, and executive function. The present review aims to create a comprehensive conceptual and empirical framework that may be helpful for the optimization of neuromodulation protocols, grounded in the synthesis of evidence derived from human studies, with the objective of enhancing cognitive performance and facilitating clinical translation. Rather than merely cataloguing heterogeneous findings, this work posits that variability in the cognitive effects of tES is largely systematic and predictable when interpreted within a metaplasticity-based framework.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

This systematic review was prospectively registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; registration number: CRD420251071720). The review process adhered to the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines to uphold standards of transparency, methodological rigor, and reproducibility.2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included in this systematic review if they met predefined eligibility criteria. Eligible studies involved human participants of any age, including healthy individuals as well as clinical populations presenting cognitive impairment, neurological disorders, or psychiatric conditions. Interventions had to employ tES techniques, including tDCS, tACS, or tRNS. Importantly, only studies implementing stimulation protocols explicitly or implicitly designed to recruit metaplasticity mechanisms were considered. These protocols included, but were not limited to, priming paradigms (e.g., cognitive, emotional, or physiological priming), repeated or multi-session stimulation, polarity sequencing, manipulation of stimulation timing (online versus offline), or multi-site stimulation approaches. Eligible studies were required to assess behavioral and/or neurophysiological markers of cognitive function, such as memory, attention, executive functions, or learning, and to relate these outcomes to state-, timing-, or history-dependent effects consistent with a metaplasticity framework. Only experimental studies published in peer-reviewed journals were included, encompassing randomized controlled trials, crossover designs, and quasi-experimental studies. Studies published in English, or providing an English-language abstract with sufficient methodological detail to allow reliable screening and data extraction, were considered eligible. Studies were excluded if they were conducted in animals, presented as case reports, reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, or conference abstracts without accessible full-text data. Additionally, studies that did not involve tES, did not assess cognitive outcomes, or applied standard single-session stimulation protocols without any metaplasticity-related manipulation were excluded.

2.3. Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was systematically conducted across the electronic databases PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, selected to provide extensive coverage of biomedical, psychological, and cognitive neuroscience research. No temporal restrictions were imposed, thereby encompassing both foundational and contemporary investigations. The search strategy integrated controlled vocabulary terms (e.g., Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] in PubMed) with free-text keywords to maximize both sensitivity and specificity. It was structured around three principal conceptual domains: (1) the intervention, encompassing terms such as *transcranial electrical stimulation*, *tDCS*, *transcranial direct current stimulation*, *tACS*, *transcranial alternating current stimulation*, *tRNS*, and *transcranial random noise stimulation*; (2) the underlying mechanism, including *metaplasticity*, *homeostatic plasticity*, *synaptic plasticity*, *priming*, *state-dependent*, and *history-dependent*; and (3) cognitive outcomes, incorporating *cognition*, *memory*, *working memory*, *executive function*, *attention*, and *learning*.

An illustrative Boolean search string employed in PubMed was: (“tDCS” OR “transcranial direct current stimulation” OR “tACS” OR “transcranial alternating current stimulation” OR “tRNS” OR “transcranial random noise stimulation”) AND (“metaplasticity” OR “homeostatic plasticity” OR “synaptic plasticity” OR “priming”) AND (“cognition” OR “memory” OR “attention” OR “executive function” OR “learning”). The search syntax was adapted as necessary for each database. In addition to electronic searches, the reference lists of included studies and pertinent review articles were manually examined to identify further eligible publications. All retrieved records were imported into reference management software, and duplicate entries were removed prior to the screening phase.

2.4. Study Selection

All records retrieved from the database searches were imported into the Rayyan systematic review platform (

https://rayyan.ai) for screening and management. Duplicate entries were identified automatically by the software and subsequently verified manually. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers using Rayyan’s blinded review function to minimize selection bias. Full-text versions were obtained for all studies deemed potentially eligible and were independently assessed against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies between reviewers at either the title/abstract or full-text screening stages were resolved through discussion, and consensus was reached in all cases; when necessary, a third reviewer was consulted to adjudicate unresolved disagreements.

2.5. Data Extraction

Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers using a standardized data extraction form developed specifically for this review. Extracted information included study characteristics (authors, year of publication, and study design), sample characteristics (sample size and population type), stimulation parameters (tES modality, stimulation intensity and duration, electrode montage, and timing of stimulation), metaplasticity-related features (such as priming paradigms, repeated sessions, polarity sequencing, or timing manipulations), cognitive domains assessed and corresponding outcome measures, main behavioral and/or neurophysiological findings, and the nature of control or comparator conditions. Any discrepancies identified during data extraction were resolved through discussion, with consensus achieved between reviewers; a third reviewer was consulted when necessary.

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

Risk of bias was assessed independently by two reviewers using tools appropriate to the study design. Randomized controlled trials were evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2), whereas non-randomized or quasi-experimental studies were assessed using the ROBINS-I tool. Disagreements in risk-of-bias judgments were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

2.7. Data Synthesis

Given the substantial heterogeneity in stimulation protocols, metaplasticity strategies, cognitive domains, and outcome measures across studies, a quantitative meta-analysis was not performed. Instead, a qualitative narrative synthesis was conducted. Studies were grouped according to stimulation modality (e.g., tDCS, tACS, tRNS), metaplasticity strategy (e.g., priming, repetition, timing or polarity sequencing), and cognitive domain assessed. Findings were interpreted with a particular emphasis on state-, timing-, and history-dependent effects relevant to metaplasticity.

2.8. Assessment of Reporting Bias

Potential reporting bias was assessed qualitatively by examining the availability of study protocols (when accessible), evaluating selective outcome reporting, and assessing the consistency between reported methods and results across studies.

2.9. Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of evidence across cognitive outcomes was evaluated using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach. This assessment considered study limitations, inconsistency of results, indirectness of evidence, imprecision of estimates, and the potential risk of publication bias.

3. Results

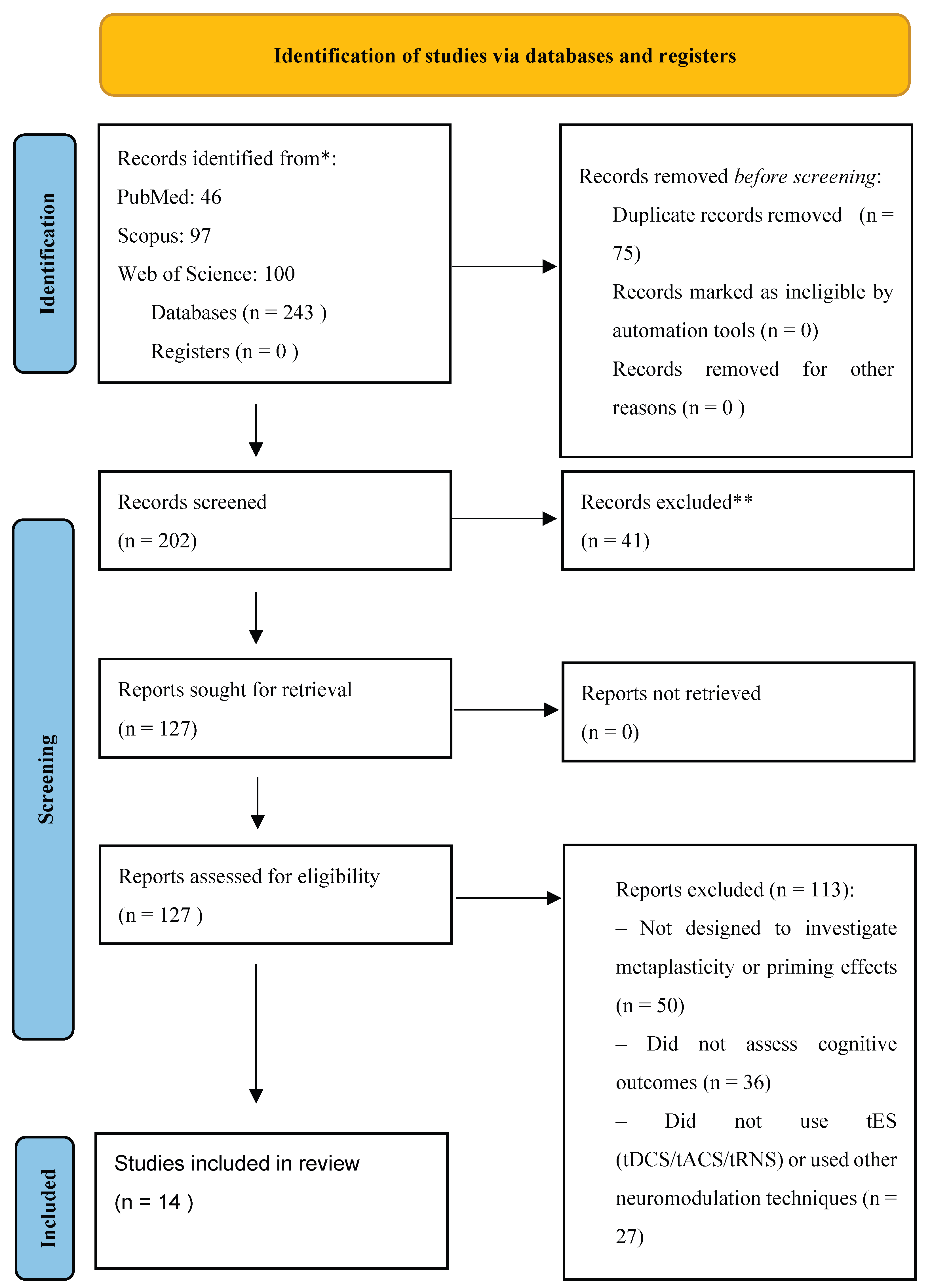

3.1. Study Selection

A total of 243 records were identified through database searches, including PubMed (n = 46), Scopus (n = 97), and Web of Science (n = 100). After removal of duplicate records (n = 75), 202 records were screened based on titles and abstracts. Of these, 41 records were excluded at this stage. The full texts of 127 articles were subsequently retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Following full-text evaluation, 113 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, primarily due to the absence of metaplasticity-related protocol features, lack of cognitive outcome measures, or use of neuromodulation techniques other than transcranial electrical stimulation. Out of the 243 records initially retrieved through database and manual searches, 14 studies ultimately met all predefined eligibility criteria and were included in the final qualitative synthesis. The stepwise progression from identification to inclusion, along with the number of records excluded at each screening stage, is presented in the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. (

Figure 2).

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies and Metaplasticity-Related Cognitive Outcomes

The 14 studies included in this systematic review were published between 2008 and 2024 and investigated metaplasticity-related effects of tES on cognitive function using diverse experimental designs and stimulation protocols (

Table 1). Across studies, tDCS was the predominant modality, employed in 13 of the 14 studies, either as a standalone intervention or combined with priming procedures, multisite stimulation, or repeated-session designs. tRNS was examined in three studies, including conventional, high-frequency, or high-definition (HD) configurations, either alone or in direct comparison with tDCS. No studies using tACS met the inclusion criteria of the present review.

Most studies were conducted in healthy adult populations, with a primary emphasis on probing the mechanisms underpinning plasticity-related cognitive modulation. A subset of studies extended to metaplasticity-focused approaches beyond strictly cognitive paradigms, by incorporating brain state manipulation such as emotional stress induction or physiological priming via exercise.

Study designs were heterogeneous, and included randomized controlled trials, within-subject crossover protocols, and between-subject factorial designs, with several studies implementing repeated stimulation sessions or task-concurrent stimulation to explore activity-dependent effects.

Similarly to what happened with study designs, stimulation parameters exhibited considerable heterogeneity across studies, varying in current intensity (typically 1–2 mA), duration (ranging from brief trial-locked stimulation to sessions lasting up to 30 min), session number (single versus repeated), timing relative to task performance (online versus offline), and electrode configuration (unilateral, bifrontal, bilateral, high-definition, or using an extracephalic reference). Importantly, every study included at least one protocol element explicitly or implicitly intended to engage metaplasticity-related processes, such as cognitive, emotional, or physiological priming; polarity sequencing; repeated stimulation; task-locked timing; or multimodal intervention strategies (

Table 1).

Regarding stimulation targets, most studies focused on the prefrontal cortex—particularly the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)—given its established role in working memory, executive control, and other higher-order cognition. Depending on the specific cognitive domain under investigation, other targets included bilateral DLPFC, posterior parietal cortex, and occipital regions. Cognitive outcomes encompassed a broad range of domains, including working memory, declarative and visuospatial memory, inhibitory control, perceptual learning, and creativity. These were primarily assessed using behavioral performance metrics, often complemented by neurophysiological measures such as EEG-derived indices of cortical excitability, inhibition, or functional connectivity.

Across studies summarized in

Table 1, the cognitive effects of tES demonstrated substantial variability in both direction and magnitude. Facilitatory outcomes were generally observed under conditions involving task engagement, optimal priming states, short inter-session intervals, or lower baseline performance levels. Conversely, null effects were frequently reported when stimulation was applied outside active task performance or in the absence of prior state modulation. In some paradigms, detrimental outcomes, such as impaired long-term memory retention during complex learning, were also reported. Notably, identical stimulation parameters occasionally yielded divergent effects (facilitatory, neutral, or detrimental) depending on contextual and temporal factors.

Collectively, the findings summarized in

Table 1 indicate that cognitive responses to tES are not uniform across protocols or individuals but instead vary systematically according to stimulation timing, protocol configuration, prior neural state, and baseline characteristics.

4. Discussion

This systematic review explored how protocol-specific features of tES influence cognitive outcomes through mechanisms that can be explained by metaplasticity, offering insights with direct implications for the evolution of neurorehabilitation technologies. Across the fourteen studies included, a converging pattern emerges: cognitive effects of tES are neither uniform nor inherently facilitatory. Instead, outcomes appear to reflect complex, state-dependent interactions between stimulation parameters and the functional neural context at the time of application. And as such, factors such as preceding neural activity, task engagement, stimulation history, temporal dynamics, and contextual modulation are critical for the tES-induced effects.

From a rehabilitation standpoint, these findings challenge the notion of tES as a purely additive or dose-dependent intervention. Rather, tES should be conceptualized as a dynamic, state-contingent modulator of ongoing plasticity processes, capable of either enhancing or constraining cognitive performance depending on its temporal and contextual integration. This metaplasticity-oriented perspective reframes tDCS, tACS, and tRNS as adaptive neuromodulatory tools whose efficacy hinges on their coordination with task demands, training schedules, and individual neurophysiological profiles, rather than on stimulation parameters alone.

In practical terms, using the mechanistic foundation of metaplasticity as a guiding principle may be useful for developing more reliable, flexible, and individualized neurorehabilitation strategies. As the field advances, incorporating behavioral and physiological markers of brain state into stimulation protocols may represent a pivotal step toward optimizing cognitive outcomes and achieving precision neuromodulation in clinical settings.

4.1. Timing- and State-Dependent Modulation of Cognitive Function

A central and theoretically significant observation across the reviewed studies concerns the pivotal influence of stimulation timing relative to ongoing cognitive processing. Rather than eliciting uniform effects, tES outcomes were highly dependent on whether stimulation was applied concurrently with active task performance (online) or outside the task context (offline). This temporal sensitivity underscores the crucial role of transient brain states in determining the direction and magnitude of plasticity induction.

Multiple studies demonstrated that tES exerted cognitive benefits only when synchronized with task-relevant neural activity. For example, Oldrati et al. [

26] reported that visuospatial learning improvements emerged exclusively under online tDCS application during training, with identical offline stimulation yielding no measurable effects. Similarly, Pirulli et al. [

29] showed that tRNS enhanced perceptual learning only when delivered online, whereas anodal tDCS produced greater effects when applied offline. Collectively, these findings reveal that identical stimulation parameters can produce distinct, and occasionally opposing, effects depending solely on task engagement, illustrating the state-dependent nature of tES-induced plasticity.

Evidence from trial-specific paradigms further refines this temporal specificity. Javadi, Cheng, and Walsh [

23] showed that brief, precisely timed stimulation during early encoding phases facilitated declarative memory formation, whereas stimulation applied post-encoding had no effect. Consistent results by Javadi and Walsh [

24] showed that stimulation influenced memory performance only when delivered during encoding, with polarity-dependent outcomes, and remained ineffective during retrieval. Together, these studies indicate that tES interacts with discrete temporal windows of neural susceptibility within which synaptic plasticity can be selectively modulated.

These findings suggest that tES does not directly impose plastic changes but instead tunes the gain of endogenous learning processes. Task engagement and associated neural activation appear to prime cortical networks, defining the physiological conditions under which stimulation can bias plasticity in a facilitatory or inhibitory manner. When delivered outside these optimal windows, identical stimulation protocols may fail to exert measurable effects or may even dampen subsequent learning capacity. From an applied and clinical perspective, the temporal alignment between stimulation and cognitive engagement emerges as a key determinant of therapeutic efficacy. These findings imply that tES should be strategically integrated with cognitive training, behavioral therapy, or task-specific rehabilitation exercises rather than administered in isolation. Designing protocols that dynamically synchronize stimulation with task demands and individual neural states may be crucial for achieving consistent and functionally meaningful outcomes in neurorehabilitation contexts.

4.2. Priming and History-Dependent Effects

A growing body of evidence converges on priming as a pivotal mechanism through which metaplasticity modulates the cognitive outcomes of tES. Across studies, tES rarely produced significant effects in isolation; rather, its efficacy depended on preceding cognitive, emotional, or physiological states that appeared to tune in neural systems for subsequent plastic modification. These preparatory conditions likely act by tuning cortical excitability and network dynamics, thereby determining whether tES facilitates or suppresses adaptive plasticity.

Cognitive priming provides a compelling demonstration of this principle. Colombo et al. [

21] reported that stimulation enhanced creative performance exclusively when participants first engaged in a divergent thinking task—an activity known to activate associative and integrative neural processes. When the same stimulation was applied following convergent thinking, or in the absence of prior cognitive engagement, no effects were observed. This pattern indicates that tES does not evoke creativity directly but rather amplifies task-relevant neural configurations that have already been mobilized through cognitive priming. The finding underscores a fundamental metaplasticity concept: the brain’s prior functional state determines the efficacy and direction of external modulation.

Emotional context has emerged as another potent modulator of stimulation efficacy. De Smet et al. [

22] showed that improvements in emotional working memory occurred only when stimulation was coupled with experimentally induced stress, whereas stimulation under neutral conditions yielded no measurable benefits. These results suggest that affective states influence prefrontal excitability and network gating, shaping the system’s responsiveness to plasticity induction. Stress-related neuromodulatory signaling—particularly changes in catecholaminergic tone—may transiently alter the threshold for long-term potentiation (LTP)-like processes, thus modulating whether tES produces facilitative or null effects. This aligns with the broader view that emotion acts as a physiological “switch” that determines when stimulation can drive meaningful plastic reorganization.

Physiological priming further extends this framework to encompass body–brain interactions. Yue et al. [

31] found that inhibitory control improved only when stimulation followed high-intensity interval exercise, while stimulation or exercise alone produced negligible effects. This synergy points to the role of exercise-induced arousal, neurotrophic factor release, and autonomic activation in modulating cortical plasticity thresholds. Such evidence suggests that transient physiological states can bias the neural milieu toward greater responsiveness, thereby increasing the likelihood that stimulation yields measurable behavioral gains. From a translational perspective, this mechanism offers a promising pathway for neurorehabilitation: strategically combining tES with physical exercise or sensorimotor training may amplify the impact of both interventions, maximizing functional recovery potential.

Finally, history-dependent effects illustrate the cumulative and directional nature of metaplastic modulation. Carvalho et al. [

20] showed that two successive cathodal tDCS sessions enhanced working memory only when separated by a short inter-session interval, whereas anodal sessions produced no improvement regardless of spacing. This polarity- and timing-specific pattern exemplifies homeostatic metaplasticity—the principle that prior stimulation history constrains subsequent plastic change. By this account, the brain dynamically adjusts its plastic potential based on preceding activity levels, maintaining network stability while permitting context-specific adaptability.

Taken together, these converging findings underscore a unifying message for the field of applied neuromodulation: the brain’s response to tES is determined not merely by the stimulation parameters in isolation but by the context (i.e., temporal, cognitive, emotional, and physiological) in which stimulation occurs. Designing effective interventions therefore requires integrating tES within broader behavioral and environmental frameworks. Priming and stimulation history should be viewed as core mechanistic determinants, not peripheral modifiers, of stimulation efficacy. Embedding these principles into protocol design may represent a decisive step toward achieving reliable, state-contingent, and individually optimized neuromodulation strategies for cognitive enhancement and rehabilitation.

4.3. Baseline Sensitivity and Individual Differences

A consistent theme emerging across the reviewed literature is that the effects of tES are profoundly influenced by baseline cognitive performance and the individual’s preexisting neural state. Rather than producing uniform benefits, tES often exerts its most pronounced effects in individuals starting from a lower functional baseline. For example, Ai et al. [

19] showed that improvements in visual working memory following high-definition stimulation were largely confined to participants with low baseline capacity. In contrast, individuals with higher baseline performance exhibited measurable neurophysiological changes but negligible behavioral enhancement. This dissociation implies that stimulation can modulate neural processing even in the absence of overt performance gains. Comparable findings were reported by Nikolin et al. [

27], who observed selective alterations in electrophysiological indices of working memory maintenance without corresponding behavioral improvements. Collectively, these results indicate that neural responsiveness and behavioral performance do not necessarily scale in parallel and that the observable impact of stimulation may differ across individuals as a function of their initial cognitive and physiological state.

From a metaplasticity standpoint, these findings are consistent with baseline-dependence models, which posit that the efficacy and direction of plasticity induction are constrained by prior neural activity levels. In this framework, tES acts not as a uniform cognitive enhancer but as a state-sensitive modulator, exerting the greatest influence when cortical networks are operating below their optimal efficiency. This interpretation provides a mechanistic basis for the substantial interindividual variability frequently noted in the literature and underscores the importance of integrating baseline measures into both experimental design and clinical application. Furthermore, it cautions against the assumption that null behavioral results equate to an absence of underlying neural modulation, emphasizing the need for concurrent neurophysiological assessment to fully capture stimulation-induced effects.

4.4. Beneficial Versus Maladaptive Metaplasticity

Crucially, metaplasticity does not inherently equate to improvement. Several studies demonstrate that tES can yield neutral or even detrimental cognitive outcomes when administered under suboptimal conditions. Pyke et al. [

30] offered a particularly illustrative example, showing that stimulation applied during complex, retrieval-based learning impaired long-term memory retention, even though immediate learning performance remained unaffected. This finding suggests that stimulation delivered at sensitive stages of memory processing may interfere with consolidation mechanisms rather than enhance them. Further evidence of non-beneficial or opposing effects emerges from studies reporting null outcomes or directionally reversed effects contingent on stimulation parameters or cognitive state. Rather than contradicting the metaplasticity account, such results reinforce it, highlighting that tES can bias neural plasticity toward either adaptive or maladaptive trajectories depending on the timing of stimulation, ongoing task demands, and the preexisting neural context.

From a translational perspective, these observations carry significant implications. They emphasize that tES cannot be presumed universally beneficial or physiologically neutral. When misaligned with cognitive state or temporal dynamics, stimulation may disrupt the very processes it aims to facilitate. This underscores the importance of precision in protocol design, particularly in neurorehabilitation contexts where interventions target already vulnerable neural systems. Optimizing stimulation timing and contextual alignment is therefore essential to ensure therapeutic efficacy and minimize the risk of iatrogenic interference with cognitive function.

4.5. Implications for Protocol Optimization and Applied Neuroscience

Collectively, the evidence synthesized in this review underscores that the design of effective tES protocols must be firmly rooted in metaplasticity principles. Across studies, beneficial effects were most consistently achieved when stimulation was temporally aligned with task-relevant neural activity, preceded by suitable cognitive or physiological priming, and tailored to participants’ stimulation history and baseline functional state. In contrast, protocols that disregarded these state- and history-dependent dynamics were more prone to yield variable, null, or even adverse outcomes.

These findings advocate for a conceptual shift in neuromodulation research—from emphasizing the magnitude or duration of stimulation toward optimizing its timing, contextual integration, and individual specificity. Embedding tES within cognitive training paradigms, emotional or physiological priming conditions, and personalized baseline assessments may substantially enhance both the efficacy and reproducibility of outcomes. Moreover, adopting a metaplasticity-informed perspective may confer important safety benefits by minimizing the risk of maladaptive plastic responses.

Ultimately, positioning metaplasticity as a central organizing framework represents a critical evolution in the field, advancing the transition from uniform, parameter-driven interventions to adaptive, context-sensitive neuromodulation. This paradigm aligns closely with emerging trends in rehabilitation technology, where personalization, temporal precision, and multimodal integration are increasingly recognized as key determinants of successful neurocognitive intervention.

4.6. Underrepresentation of tACS and tRNS and Directions for Future Research

Despite their strong theoretical relevance to metaplasticity research, one of the clearest observations from this review is the pronounced underrepresentation of tACS and tRNS in human cognitive studies explicitly designed to engage metaplastic mechanisms. Among the fourteen studies that met inclusion criteria, the large majority employed tDCS, with only a small subset incorporating tRNS and none integrating tACS within a metaplasticity-oriented cognitive framework. This methodological bias defines a significant limitation of the current evidence base and highlights a critical avenue for future inquiry.

From a mechanistic standpoint, this absence is especially notable. In contrast to tDCS, which primarily induces tonic alterations in cortical excitability, tACS interfaces directly with the temporal structure of neural activity, modulating oscillatory phase, frequency, and synchrony. Given that both synaptic plasticity and metaplasticity are intrinsically dependent on oscillatory dynamics and their temporal coordination, tACS is uniquely positioned to probe frequency- and phase-specific thresholds for plasticity induction, as well as history-dependent modulation of large-scale network synchronization. Yet, to date, these temporally structured mechanisms remain largely unexamined within the domain of human cognition using oscillatory stimulation paradigms.

Similarly, tRNS represents an underexplored but mechanistically promising modality for metaplasticity-informed cognitive modulation. By introducing controlled stochastic perturbations across a broad frequency range, tRNS is proposed to enhance neural signal fidelity through stochastic resonance. Within a metaplastic framework, such noise-induced fluctuations may act as a permissive or threshold-lowering process, thereby facilitating subsequent learning-related or task-evoked plasticity. These characteristics are particularly relevant for neural systems operating below optimal efficiency, such as individuals with low baseline cognitive performance or early neurocognitive vulnerability. However, systematic investigations assessing how stimulation timing, prior neural state, or priming conditions interact with tRNS-induced cognitive outcomes remain exceedingly limited.

The limited use of tACS and tRNS likely reflects both historical and methodological factors, including greater interindividual variability, the technical complexity of parameter optimization (e.g., frequency, bandwidth, phase alignment), and a legacy of smaller or less consistent behavioral effects relative to tDCS. Nonetheless, recent methodological advances, such as individualized stimulation modeling, closed-loop designs, and concurrent multimodal neurophysiological monitoring, now provide concrete strategies to address these challenges. In particular, the integration of real-time EEG or task-based neural markers holds substantial promise for exploiting the metaplastic potential of tACS and tRNS with greater temporal precision. Looking forward, future research must expand beyond the dominant tDCS paradigm to systematically examine tACS and tRNS within explicitly metaplasticity-informed experimental designs. This entails deliberate manipulation of antecedent brain state, oscillatory context, stimulation history, and cognitive engagement, as well as direct within-study comparisons across tES modalities. Such efforts will be essential for disentangling the distinct and potentially synergistic mechanisms through which different stimulation waveforms interact with endogenous plasticity.

Accordingly, the current predominance of tDCS in the metaplasticity literature should be regarded as a reflection of historical accessibility rather than mechanistic superiority. Broadening the empirical scope to include tACS and tRNS is vital for capturing the temporal, oscillatory, and probabilistic dimensions of human neuroplasticity and for driving the next generation of adaptive, individualized, and precision-based neuromodulation approaches in both cognitive enhancement and clinical rehabilitation contexts.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrates that the cognitive effects of tES are governed also by metaplasticity-related mechanisms, rather than by stimulation parameters alone. Across the fourteen studies examined, cognitive outcomes were consistently shaped by dynamic interactions among brain state, timing relative to task engagement, stimulation history, priming context, and individual baseline performance. Collectively, the evidence indicates that tES does not produce uniform or additive effects on cognition but instead acts as a state-dependent modulator that interacts with ongoing neural activity and prior plastic adaptations.

Across diverse experimental paradigms, stimulation yielded the most robust enhancements when precisely aligned with task-relevant neural processing, preceded by appropriate cognitive, emotional, or physiological priming, and tailored to individual baseline characteristics. In contrast, stimulation applied outside these optimal temporal or contextual windows frequently produced null or even detrimental effects, including disruptions of long-term memory consolidation. These findings underscore the importance of conceptualizing tES not as a general-purpose enhancer, but as a context-sensitive intervention whose impact is governed by metaplastic constraints.

From an applied and translational perspective, this evidence carries significant implications for neurorehabilitation and cognitive intervention design. Optimal protocol development should emphasize timing, contextual integration, and individualization rather than the mere adjustment of stimulation intensity or duration. Embedding tES within multimodal frameworks, combining stimulation with cognitive training, physical exercise, or affective engagement, offers a promising path toward improving efficacy, reducing interindividual variability, and mitigating maladaptive outcomes.

In conclusion, adopting a metaplasticity-informed framework provides a unifying explanation for the heterogeneity observed across the tES literature and establishes a principled foundation for advancing the field toward more precise, adaptive, and safe cognitive neuromodulation. Future clinical and rehabilitative applications will depend on protocols that explicitly leverage metaplastic principles to determine when, how, and for whom tES should be applied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.; methodology, S.C.; protocol registration, S.C.; literature search, S.C. and J.L.; study selection, S.C. and J.L.; data extraction, S.C. and J.L.; risk of bias assessment, S.C. and J.L.; data synthesis and interpretation, S.C. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, S.C. and J.L.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, S.C. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

N/A.

Informed Consent Statement

N/A.

Data Availability Statement

N/A.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5, 2025) for assistance in language editing, formatting, and figure preparation. The authors have reviewed and edited all AI-generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviation |

Definition |

| tES |

Transcranial Electrical Stimulation |

| tDCS |

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| tACS |

Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation |

| tRNS |

Transcranial Random Noise Stimulation |

| DLPFC |

Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex |

| NIBS |

Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation |

References

- Abraham, W.C.; Bear, M.F. Metaplasticity: The plasticity of synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 1996, 19, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, S.R.; Jones, O.D.; Raymond, C.R.; Sah, P.; Abraham, W.C. Mechanisms of heterosynaptic metaplasticity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 369, 20130148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantone, M.; Lanza, G.; Ranieri, F.; Opie, G.M.; Terranova, C. Editorial: Non-invasive brain stimulation in the study and modulation of metaplasticity in neurological disorders. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 721906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Dahlhaus, F.; Ziemann, U. Metaplasticity in human cortex. Neuroscientist 2014, 21, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J. Physiol. 2000, 527, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, C.J.; Nitsche, M.A. Physiological basis of transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroscientist 2011, 17, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmashiri, A.; Akbari, F. The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on cognitive functions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2025, 35, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.; Leite, J.; Fregni, F. Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation and Transcranial Random Noise Stimulation. In Neuromodulation, 2nd ed.; Lozano, A.M., Hallett, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.S.; Rach, S.; Neuling, T.; Strüber, D. Transcranial alternating current stimulation: A review of the underlying mechanisms and modulation of cognitive processes. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, R.F.; Schneider, T.R.; Rach, S.; Trautmann-Lengsfeld, S.A.; Engel, A.K.; Herrmann, C.S. Entrainment of brain oscillations by transcranial alternating current stimulation. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.; Gonçalves, Ó.F.; Carvalho, S. Speed of Processing Training Plus α-tACS in People with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Double-Blind, Parallel, Placebo-Controlled Trial Study Protocol. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 880510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, A.J.; Lema, A.; Carvalho, S.; Leite, J. Tailoring transcranial alternating current stimulation based on endogenous event-related P3 to modulate premature responses: A feasibility study. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliadze, V.; Antal, A.; Paulus, W. Boosting brain excitability by transcranial high-frequency stimulation in the ripple range. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 4891–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lema, A.; Carvalho, S.; Fregni, F.; Gonçalves, Ó.F.; Leite, J. The effects of direct current stimulation and random noise stimulation on attention networks. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terney, D.; Chaieb, L.; Moliadze, V.; Antal, A.; Paulus, W. Increasing human brain excitability by transcranial high-frequency random noise stimulation. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 14147–14155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Groen, O.; Potok, W.; Wenderoth, N.; Edwards, G.; Mattingley, J.B.; Edwards, D. Using noise for the better: The effects of transcranial random noise stimulation on the brain and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 138, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Dahlhaus, F.; Ziemann, U. Metaplasticity in human cortex. Neuroscientist 2015, 21, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantone, M.; Lanza, G.; Ranieri, F.; Opie, G.M.; Terranova, C. Editorial: Non-invasive Brain Stimulation in the Study and Modulation of Metaplasticity in Neurological Disorders. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 721906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Y.; Yin, M.; Zhang, L.; Hu, H.; Zheng, H.; Feng, W.; Ku, Y.; Hu, X. Effects of Different Types of High-Definition Transcranial Electrical Stimulation on Visual Working Memory and Contralateral Delayed Activity. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2024, 21, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.; Boggio, P.S.; Gonçalves, Ó.F.; Vigário, A.R.; Faria, M.; Silva, S.; Gaudencio do Rego, G.; Fregni, F.; Leite, J. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation-Based Metaplasticity Protocols in Working Memory. Brain Stimul. 2015, 8, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, B.; Bartesaghi, N.; Simonelli, L.; Antonietti, A. The Combined Effects of Neurostimulation and Priming on Creative Thinking: A Preliminary tDCS Study on the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, S.; Razza, L.B.; Pulopulos, M.M.; De Raedt, R.; Baeken, C.; Brunoni, A.R.; Vanderhasselt, M.A. Stress Priming Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) Enhances Updating of Emotional Content in Working Memory. Brain Stimul. 2024, 17(2), 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadi, A.H.; Cheng, P.; Walsh, V. Short Duration Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) Modulates Verbal Memory. Brain Stimul. 2012, 5(4), 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadi, A.H.; Walsh, V. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Modulates Declarative Memory. Brain Stimul. 2012, 5(3), 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafontaine, M.-P.; Théoret, H.; Gosselin, F.; Lippé, S. Transcranial direct current stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex modulates repetition suppression to unfamiliar faces: An ERP study. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e81721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldrati, V.; Colombo, B.; Antonietti, A. Combination of a short cognitive training and tDCS to enhance visuospatial skills: A comparison between online and offline neuromodulation. Brain Research 2018, 1678, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolin, S.; Martin, D.; Loo, C.K.; Boonstra, T.W. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Modulates Working Memory Maintenance Processes in Healthy Individuals. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2023, 35(3), 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohn, S.H.; Park, C.I.; Yoo, W.K.; Ko, M.H.; Choi, K.P.; Kim, G.M.; Lee, Y.T.; Kim, Y.H. Time-Dependent Effect of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on the Enhancement of Working Memory. NeuroReport 2008, 19(1), 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirulli, C.; Fertonani, A.; Miniussi, C. The Role of Timing in the Induction of Neuromodulation in Perceptual Learning by Transcranial Electric Stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2013, 6(4), 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, W.; Vostanis, A.; Javadi, A.H. Electrical Brain Stimulation during a Retrieval-Based Learning Task Can Impair Long-Term Memory. J. Cogn. Enhanc. 2021, 5, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Liu, L.; Nitsche, M.A.; Kong, Z.; Zhang, M.; Qi, F. Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training Combined with Dual-Site Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Inhibitory Control and Working Memory in Healthy Adults. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2024, 96, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |