Submitted:

19 December 2025

Posted:

22 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

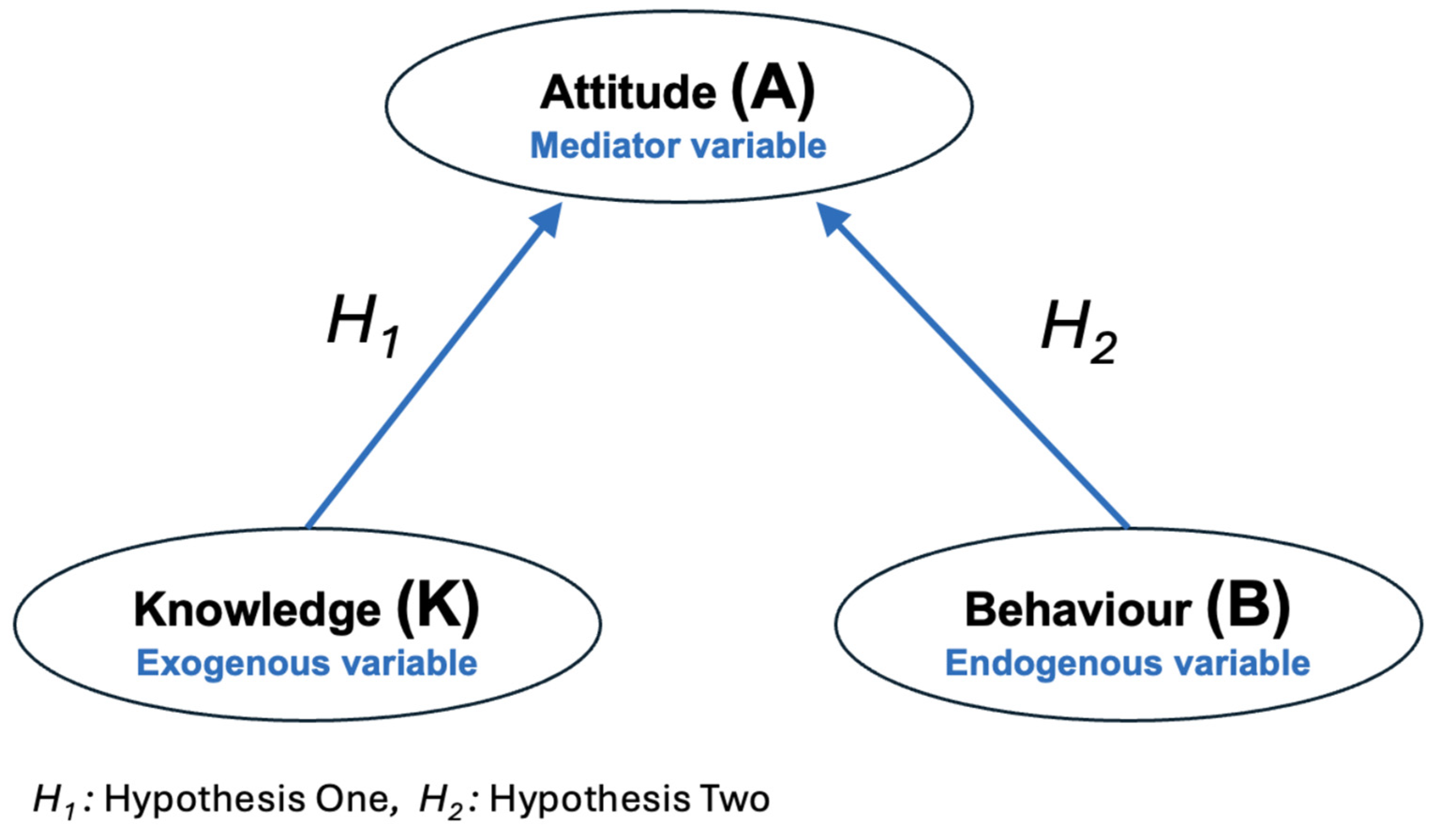

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Tool Development and Validation

Items and Domains Development

2.3. Validation and Reliability Assessment

2.4. Tool Description

2.5. Study Population and Participants’ Recruitment

2.6. Data Collection Procedures

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations and Approvals

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Model Global-Fits-Indices

3.3. Path Analysis Output

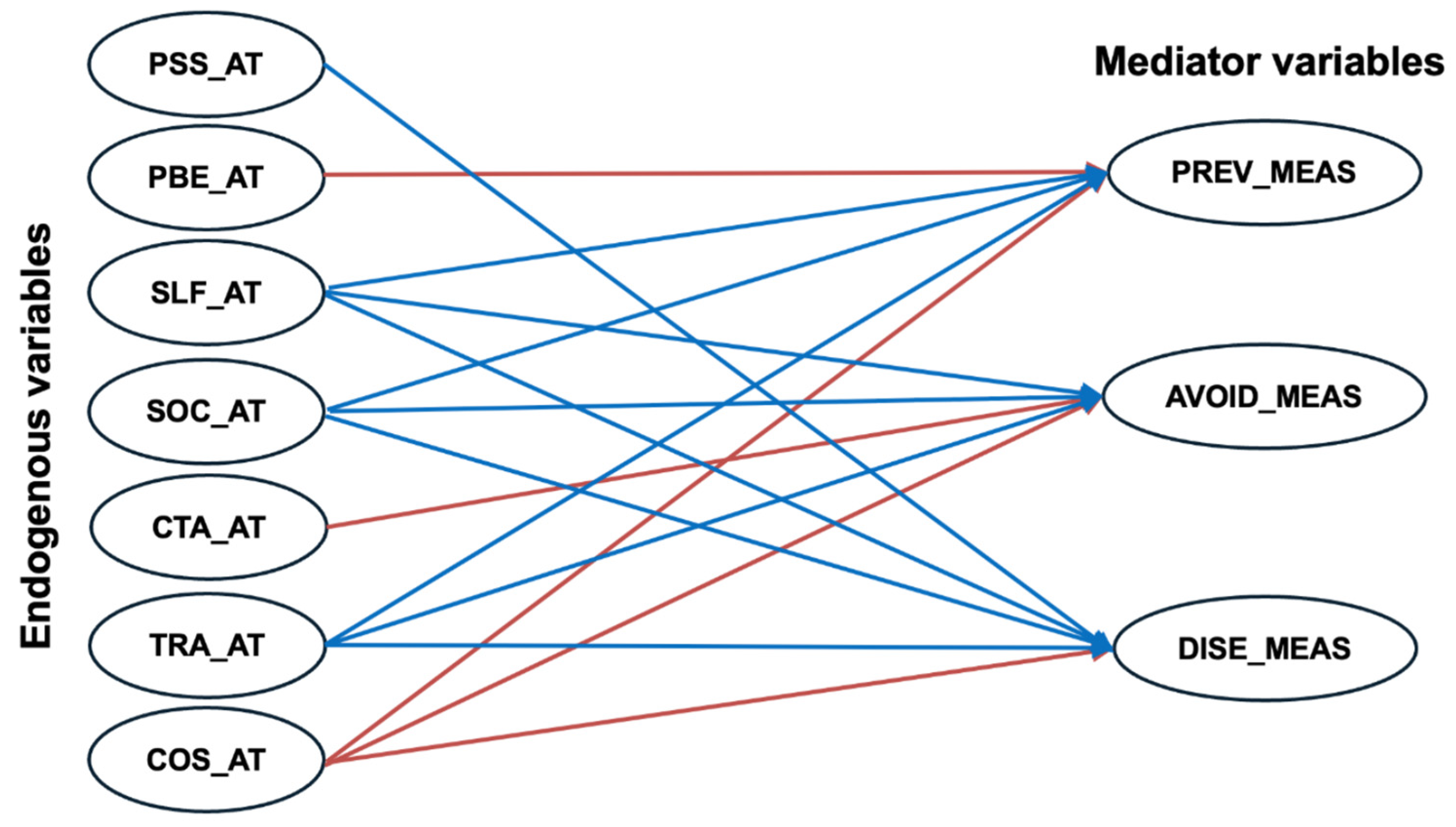

3.3.1. The Relationship Between Mediator and Endogenous Variables

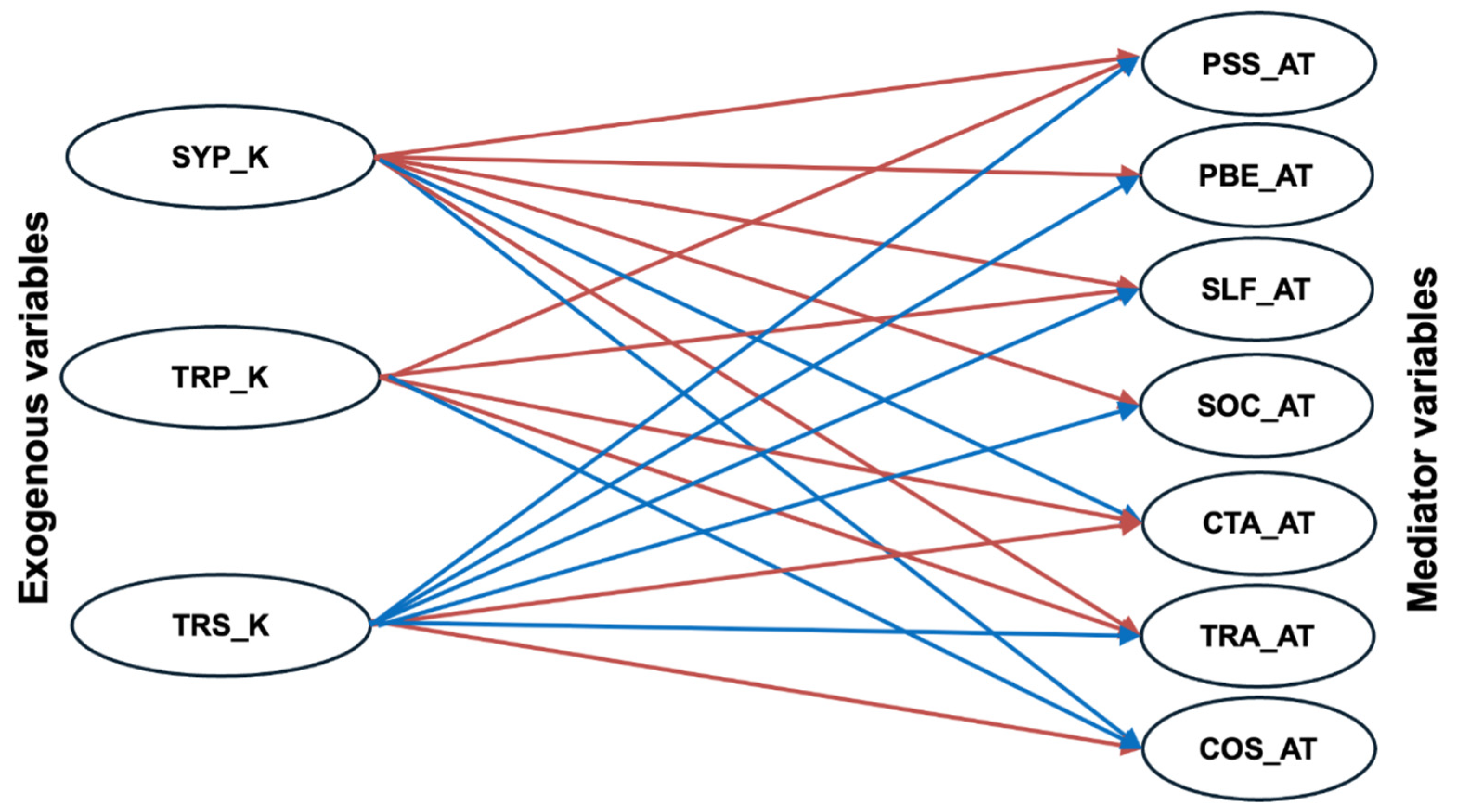

3.3.2. The Relationship Between Mediator and Exogenous Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | Attitude |

| CHERRIES | Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease of 2019 |

| B | Behaviour |

| HBM | Health Belief Model |

| HEI | Higher Education Institution |

| K | Knowledge |

| KAB | Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour model |

| MoH | Ministry of Health |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SEM | Structural Equation Model |

| SRMR | Standardised Root Mean Square Residual |

| TLI | The Tucker-Lewis Index |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

References

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020: WHO; 2020 [updated 11 March 202030 July 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it: WHO; 2020 [21 June 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it.

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). Off-label use of medicines for COVID-19: WHO; 2020 [updated 31 March 202030 July 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/off-label-use-of-medicines-for-covid-19.

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). Responding to community spread of COVID-19: interim guidance, 7 March 2020. World Health Organization; 2020.

- Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, Chapman A, Persad E, Klerings I, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020(4).

- US Department of Health-Human Services. Interim pre-pandemic planning guidance: Community strategy for pandemic influenza mitigation in the United States—Early targeted layered use of nonpharmaceutical interventions. Washington (District of Columbia): US Department of Health and Human Services. 2007.

- Tanne JH, Hayasaki E, Zastrow M, Pulla P, Smith P, Rada AG. Covid-19: how doctors and healthcare systems are tackling coronavirus worldwide. BMJ. 2020;368.

- Bedford J, Enria D, Giesecke J, Heymann DL, Ihekweazu C, Kobinger G, et al. COVID-19: towards controlling of a pandemic. The Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1015-8.

- Al Sharif O. Jordan announces lockdown in effort to contain coronavirus. Al-Monitor. 2020.

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public: Mythbusters: WHO; 2020 [5 July 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/myth-busters.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Learn about COVID-19 and how it spreads The United States (USA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),; 2024 [13 June 2024]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/about/index.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fprevent-getting-sick%2Fhow-covid-spreads.html.

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): How is it transmitted? Geneva The World Health Organisation 2021 [updated 23 December 202113 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted.

- Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schünemann HJ, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973-87.

- Gormley M, Marawska L, Milton D. It is time to address airborne transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clinical infectious diseases. 2020;71(9):2311-3.

- Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, Capraro V, Cichocka A, Cikara M, et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature human behaviour. 2020;4(5):460-71.

- Abdelrahman M. Personality traits, risk perception, and protective behaviors of Arab residents of Qatar during the COVID-19 pandemic. International journal of mental health and addiction. 2022;20(1):237-48.

- Zickfeld J, Schubert T, Herting A, Grahe J, Faasse K. Predictors of health-protective behavior and changes over time during the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Retrieved from osf io/crs2n. 2020.

- Brehm SS, Brehm JW. Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control: Academic Press; 2013.

- Geller ES. The challenge of increasing proenvironment behavior. Handbook of environmental psychology. 2002;2(396):525-40.

- Locke EA. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Personnel psychology. 1997;50(3):801.

- Matson-Koffman DM, Brownstein JN, Neiner JA, Greaney ML. A site-specific literature review of policy and environmental interventions that promote physical activity and nutrition for cardiovascular health: what works? American Journal of Health Promotion. 2005;19(3):167-93.

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes. 1991;50(2):179-211.

- Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health education monographs. 1974;2(4):328-35.

- Azlan AA, Hamzah MR, Sern TJ, Ayub SH, Mohamad E. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in Malaysia. Plos one. 2020;15(5):e0233668.

- Limbu DK, Piryani RM, Sunny AK. Healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitude and practices during the COVID-19 pandemic response in a tertiary care hospital of Nepal. PloS one. 2020;15(11):e0242126.

- Tang CS-k, Wong C-y. Factors influencing the wearing of facemasks to prevent the severe acute respiratory syndrome among adult Chinese in Hong Kong. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39(6):1187-93.

- Morrison LG, Yardley L. What infection control measures will people carry out to reduce transmission of pandemic influenza? A focus group study. BMC public health. 2009;9(1):258.

- Jones JH, Salathe M. Early assessment of anxiety and behavioral response to novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1). PLoS one. 2009;4(12):e8032.

- Yap J, Lee VJ, Yau TY, Ng TP, Tor P-C. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards pandemic influenza among cases, close contacts, and healthcare workers in tropical Singapore: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):442.

- Bish A, Michie S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. British journal of health psychology. 2010;15(4):797-824.

- The World Health Organization (WHO). A guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. Switzerland: WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. 2008.

- Rubin GJ, Bakhshi S, Amlôt R, Fear N, Potts HW, Michie S. The design of a survey questionnaire to measure perceptions and behaviour during an influenza pandemic: the Flu TElephone Survey Template (FluTEST). 2014.

- Bloom BS. Learning for Mastery. Instruction and Curriculum. Regional Education Laboratory for the Carolinas and Virginia, Topical Papers and Reprints, Number 1. Evaluation comment. 1968;1(2):n2.

- Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal. 1999;6(1):1-55.

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling: Guilford publications; 2015.

- Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling: psychology press; 2004.

- Devlieger I, Talloen W, Rosseel Y. New developments in factor score regression: Fit indices and a model comparison test. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2019;79(6):1017-37.

- Idris M, Alkhawaja L, Ibrahim H. Gender disparities among students at Jordanian universities during COVID-19. International Journal of Educational Development. 2023;99:102776.

- The Ministry of Higher Education. Annual Statistical Report. Amman-Jordan The Ministry of Higher Education; 2020.

- Bailey SC, Serper M, Opsasnick L, Persell SD, O’Conor R, Curtis LM, et al. Changes in COVID-19 knowledge, beliefs, behaviors, and preparedness among high-risk adults from the onset to the acceleration phase of the US outbreak. Journal of general internal medicine. 2020;35:3285-92.

- Quinn SC, Kumar S. Health inequalities and infectious disease epidemics: a challenge for global health security. Biosecurity and bioterrorism: biodefense strategy, practice, and science. 2014;12(5):263-73.

- Zhao Y, Zhang J. Consumer health information seeking in social media: a literature review. Health Information & Libraries Journal. 2017;34(4):268-83.

- Ferdous MZ, Islam MS, Sikder MT, Mosaddek ASM, Zegarra-Valdivia JA, Gozal D. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding COVID-19 outbreak in Bangladesh: An online-based cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2020;15(10):e0239254.

- Zhong B-L, Luo W, Li H-M, Zhang Q-Q, Liu X-G, Li W-T, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. International journal of biological sciences. 2020;16(10):1745.

- Chang J-H, Han D, Wang D. Comparison of Mental Health Status and Behaviour of Chinese Medical and Non-Medical College Students During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Psychosom Med Res. 2021;3:42-52.

- Zhu X, Liu J. Education in and after Covid-19: Immediate responses and long-term visions. Postdigital Science and Education. 2020;2:695-9.

- Wang X, Hegde S, Son C, Keller B, Smith A, Sasangohar F. Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of medical Internet research. 2020;22(9):e22817.

- Peng Y, Pei C, Zheng Y, Wang J, Zhang K, Zheng Z, et al. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitude and practice associated with COVID-19 among undergraduate students in China. BMC public health. 2020;20:1-8.

- Zhang M, Li Q, Du X, Zuo D, Ding Y, Tan X, et al. Health behavior toward COVID-19: the role of demographic factors, knowledge, and attitude among Chinese college students during the quarantine period. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2020;32(8):533-5.

- Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health education quarterly. 1988;15(2):175-83.

- Adli I, Widyahening IS, Lazarus G, Phowira J, Baihaqi LA, Ariffandi B, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice related to the COVID-19 pandemic among undergraduate medical students in Indonesia: A nationwide cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2022;17(1):e0262827.

- Pather N, Blyth P, Chapman JA, Dayal MR, Flack NA, Fogg QA, et al. Forced disruption of anatomy education in Australia and New Zealand: An acute response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Anatomical sciences education. 2020;13(3):284-300.

- Gardanova Z, Belaia O, Zuevskaya S, Turkadze K, Strielkowski W, editors. Lessons for medical and health education learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare; 2023: MDPI.

- Ross DA. Creating a “quarantine curriculum” to enhance teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Academic Medicine. 2020;95(8):1125-6.

- Boutros P, Kassem N, Nieder J, Jaramillo C, von Petersdorff J, Walsh FJ, et al., editors. Education and training adaptations for health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review of lessons learned and innovations. Healthcare; 2023: MDPI.

- Bults M, Beaujean DJ, Richardus JH, Voeten HA. Perceptions and behavioral responses of the general public during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic: a systematic review. Disaster medicine and public health preparedness. 2015;9(2):207-19.

- Reuben RC, Danladi MM, Saleh DA, Ejembi PE. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: an epidemiological survey in North-Central Nigeria. Journal of community health. 2021;46(3):457-70.

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Geneva: World Health Organisation 2020 [30 July 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/india/emergencies/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)#:~:text=On%2011%20March%202020%2C%20WHO,transmission%20to%20save%20people’s%20lives.

- The Ministry of Health (MoH). The COVID 19 Amman-Jordan The Ministry of Health (MoH); 2022 [13 August 2024]. Available from: https://corona.moh.gov.jo/en.

- Rana MM, Karim MR, Wadood MA, Kabir MM, Alam MM, Yeasmin F, et al. Knowledge of prevention of COVID-19 among the general people in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study in Rajshahi district. PloS one. 2020;15(12):e0243410.

- Rabbani MG, Akter O, Hasan MZ, Samad N, Mahmood SS, Joarder T. COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and practices among people in Bangladesh: telephone-based cross-sectional survey. JMIR Formative Research. 2021;5(11):e28344.

- Champion VL, Skinner CS. The health belief model. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 2008;4:45-65.

- Huang J, Zheng R, Emery S. Assessing the impact of the national smoking ban in indoor public places in china: evidence from quit smoking related online searches. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e65577.

- Kaliyaperumal K. Guideline for conducting a knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) study. AECS illumination. 2004;4(1):7-9.

- Launiala A. How much can a KAP survey tell us about people’s knowledge, attitudes and practices? Some observations from medical anthropology research on malaria in pregnancy in Malawi. Anthropology Matters. 2009;11(1).

- Rimal RN, Real K. Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change: Use of the risk perception attitude (RPA) framework to understand health behaviors. Human communication research. 2003;29(3):370-99.

- Schwarzer R. Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied psychology. 2008;57(1):1-29.

- Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Communication theory. 2003;13(2):164-83.

- Jiang X, Elam G, Yuen C, Voeten H, de Zwart O, Veldhuijzen I, et al. The perceived threat of SARS and its impact on precautionary actions and adverse consequences: a qualitative study among Chinese communities in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;16:58-67.

- Goodwin R, Haque S, Neto F, Myers LB. Initial psychological responses to Influenza A, H1N1 (“ Swine flu”). BMC Infectious Diseases. 2009;9:1-6.

- Cava MA, Fay KE, Beanlands HJ, McCay EA, Wignall R. Risk perception and compliance with quarantine during the SARS outbreak. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2005;37(4):343-7.

- Brug J, Aro AR, Oenema A, De Zwart O, Richardus JH, Bishop GD. SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, the Netherlands. Emerging infectious diseases. 2004;10(8):1486.

- Barr M, Raphael B, Taylor M, Stevens G, Jorm L, Giffin M, et al. Pandemic influenza in Australia: using telephone surveys to measure perceptions of threat and willingness to comply. BMC infectious diseases. 2008;8:1-14.

- Gercek A, Demirbas T, Giray F, Oguzlar A, Yuce M. The Factors Influencing Taxpayers’ Acceptance of E-Taxation System. Handbook of Research on Strategic Developments and Regulatory Practice in Global Finance: IGI Global; 2015. p. 105-21.

| Domain * | Construct | Details | |

| Knowledge (Exogenous Variable) | Symptoms Knowledge | Definition | The awareness and understanding of COVID-19 signs and symptoms |

| No. of Items† | 9 | ||

| Code | SYP_K | ||

| Used Scale | True, False, Do not Know | ||

| Treatment Knowledge | Definition | The comprehension and awareness an individual has about different approaches and interventions available to treat and manage COVID-19 | |

| No. of Items† | 10 | ||

| Code | TRP_K | ||

| Used Scale | True, False, Do not Know | ||

| Transmission Knowledge | Definition | The awareness and understanding of how COVID-19 transmits from one person to another or from the environment to a person | |

| No. of Items† | 12 | ||

| Code | TRS_K | ||

| Used Scale | True, False, Do not Know | ||

| Attitude (Mediator Variable) | Perceived Susceptibility and Severity | Definition | The perception about the likelihood of acquiring COVID-19 and being infected |

| No. of Items† | 7 | ||

| Code | PSS_AT | ||

| Used Scale | Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree | ||

| Perceived Efficacy of Behaviour | Definition | The perceived efficacy of a specific action or behaviour in attaining a COVID-19-related outcome | |

| No. of Items† | 13 | ||

| Code | PBE_AT | ||

| Used Scale | Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree | ||

| Perceived Self-efficacy | Definition | The perception of the ability to carry out and perform COVID-19 preventive and avoidance practices | |

| No. of Items† | 13 | ||

| Code | SLF_AT | ||

| Used Scale | Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree | ||

| Social Pressure | Definition | The perception regarding the expectations of the closed social cycle or authorities of an individual’s behaviour to avoid COVID-19 | |

| No. of Items† | 14 | ||

| Code | SOC_AT | ||

| Used Scale | Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree | ||

| Cues to Action | Definition | The environmental or self-based stimuli motivate an individual to engage in a certain behaviour linked to COVID-19 | |

| No. of Items† | 12 | ||

| Code | CTA_AT | ||

| Used Scale | Yes, No, Unsure | ||

| Trust in Authority | Definition | The perception regarding authority openness and transparency in communications related to COVID-19 | |

| No. of Items† | 4 | ||

| Code | TRA_AT | ||

| Used Scale | Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree | ||

| Perceived Cost | Definition | The perception regarding practical barriers to COVID-19-related behaviours, such as financial cost and time constraints | |

| No. of Items† | 15 | ||

| Code | COS_AT | ||

| Used Scale | Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree | ||

| Behaviour (endogenous Variable) | Avoidance Behaviour | Definition | The deliberate acts and tactics that individuals adopt in order to avert contact with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is responsible for causing COVID-19 |

| No. of Items† | 8 | ||

| Code | AVO_BEH | ||

| Used Scale | Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often and Always | ||

| Preventive Behaviour | Definition | Measures implemented to minimise the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, responsible for causing COVID-19 | |

| No. of Items† | 5 | ||

| Code | PRE_BEH | ||

| Used Scale | Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often and Always | ||

| Disease Awareness Behaviour | Definition | The acts and practices individuals adopt to improve their understanding of COVID-19 and effectively reduce the risk of infection and transmission | |

| No. of Items† | TRT_BEH | ||

| Code | 3 | ||

| Used Scale | Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often and Always | ||

| Domain | Category * | Total Score | (%) |

| Knowledge (K) | High | 25-31 out of 31 | 80–100% |

| Moderate | 19-24 out of 31 | 60–79% | |

| Low | < 19 out of 31 | <60% | |

| Attitude (A) | Positive | 293-366 out 366 | 80–100% |

| Neutral | 220-292 out of 366 | 60–79% | |

| Negative | < 220 out of 366 | <60% | |

| Behaviour (B) | Good | 64-80 out of 80 | 80–100% |

| Fair | 48-63 out of 80 | 60–79% | |

| Poor | < 48 out of 80 | <60% |

| Attributes | Participants’ Group | ||

|

Health Faculties 1 N (%) |

Scientific Faculties 2 N (%) |

Humanitarian Faculties 3 N (%) |

|

| Demographics and characteristics | |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 182 (67.2%) | 201 (61.3%) | 528 (68.0%) |

| Male | 85 (31.4%) | 115 (35.1%) | 227 (29.3%) |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (1.5%) | 12 (3.7%) | 21 (2.7%) |

| Age | |||

| Average (± SD) | 20.4 ± (3.8) | 19.4 ± (1.51) | 19.6 ± (2.78) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 266 (98.2%) | 318 (97.0%) | 755 (97.3%) |

| Married | 2 (0.7%) | 4 (1.2%) | 10 (1.3%) |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (1.1%) | 6 (1.8%) | 11 (1.4%) |

| Knowledge, attitude and behaviour scores | |||

| Knowledge * | |||

| High | 10 (3.7%) | 3 (0.9%) | 5 (0.6%) |

| Moderate | 51 (18.8%) | 32 (9.8%) | 47 (6.1%) |

| Low | 210 (77.5%) | 293 (89.3%) | 724 (93.3%) |

| Attitude † | |||

| Positive | 42 (15.5%) | 61 (18.6%) | 146 (18.8%) |

| Neutral | 216 (79.7%) | 230 (70.1%) | 558 (71.9%) |

| Negative | 13 (4.8%) | 37 (11.3%) | 72 (9.3%) |

| Behaviour ‡ | |||

| Good | 144 (53.1%) | 178 (54.3%) | 483 (62.2%) |

| Fair | 98 (36.2%) | 105 (32.0%) | 221 (28.5%) |

| Poor | 29 (10.7%) | 45 (13.7%) | 72 (9.3%) |

| Construct | Est. | S.E | Z.-value | P-value | Std.All | ||

| The Behaviour-Attitude Relationship (Endogenous and Mediator Variables ) | Preventive Behaviours | PSS_AT | 0.0018 | 0.0183 | 0.0968 | 0.9229 | 0.0025 |

| PBE_AT | -0.0742 | 0.0363 | -2.0435 | 0.0410 | -0.0760 | ||

| SLF_AT* | 0.4942 | 0.0417 | 11.8654 | 0.0000 | 0.4972 | ||

| SOC_AT* | 0.1570 | 0.0348 | 4.5056 | 0.0000 | 0.1616 | ||

| CTA-AT | -0.0414 | 0.0304 | -1.3644 | 0.1724 | -0.0314 | ||

| TRA_AT* | 0.1103 | 0.0162 | 6.8140 | 0.0000 | 0.1847 | ||

| COS_AT* | -0.1471 | 0.0288 | -5.0996 | 0.0000 | -0.1221 | ||

| Avoidance Behaviours | PSS_AT | 0.0335 | 0.0226 | 1.4817 | 0.1384 | 0.0377 | |

| PBE_AT | 0.0749 | 0.0445 | 1.6823 | 0.0925 | 0.0625 | ||

| SLF_AT* | 0.3246 | 0.0479 | 6.7823 | 0.0000 | 0.2656 | ||

| SOC_AT* | 0.2627 | 0.0432 | 6.0868 | 0.0000 | 0.2200 | ||

| CTA-AT | -0.1368 | 0.0376 | -3.6340 | 0.0003 | -0.0843 | ||

| TRA_AT* | 0.1235 | 0.0198 | 6.2306 | 0.0000 | 0.1682 | ||

| COS_AT* | -0.1520 | 0.0350 | -4.3417 | 0.0000 | -0.1026 | ||

| Disease Awareness Behaviours | PSS_AT | 0.0602 | 0.0304 | 1.9787 | 0.0478 | 0.0538 | |

| PBE_AT | -0.0767 | 0.0600 | -1.2792 | 0.2008 | -0.0507 | ||

| SLF_AT* | 0.4726 | 0.0640 | 7.3811 | 0.0000 | 0.3063 | ||

| SOC_AT* | 0.2436 | 0.0574 | 4.2452 | 0.0000 | 0.1616 | ||

| CTA-AT | -0.0682 | 0.0504 | -1.3534 | 0.1759 | -0.0333 | ||

| TRA_AT* | 0.2178 | 0.0266 | 8.1832 | 0.0000 | 0.2349 | ||

| COS_AT* | -0.2558 | 0.0477 | -5.3626 | 0.0000 | -0.1368 | ||

| The Attitude-Knowledge Relationship (Mediator and Exogenous Variables ) | Perceived Susceptibility and Severity | SYP_K* | -1.3319 | 0.3467 | -3.8416 | 0.0001 | -0.2819 |

| TRP_K* | -0.5898 | 0.1636 | -3.6047 | 0.0003 | -0.1355 | ||

| TRS_K* | 2.7356 | 0.3597 | 7.6045 | 0.0000 | 0.6160 | ||

| Perceived Efficacy of Behaviour | SYP_K* | -2.8605 | 0.3854 | -7.4218 | 0.0000 | -0.8187 | |

| TRP_K | -0.0484 | 0.1465 | -0.3302 | 0.7412 | -0.0150 | ||

| TRS_K* | 4.6951 | 0.4574 | 10.2641 | 0.0000 | 1.4295 | ||

| Perceived Self-efficacy | SYP_K* | -3.4048 | 0.4223 | -8.0621 | 0.0000 | -0.9932 | |

| TRP_K | -0.3715 | 0.1595 | -2.3291 | 0.0199 | -0.1176 | ||

| TRS_K* | 4.8184 | 0.4726 | 10.1954 | 0.0000 | 1.4952 | ||

| Social Pressure | SYP_K* | -3.2212 | 0.4078 | -7.8993 | 0.0000 | -0.9184 | |

| TRP_K | -0.1603 | 0.1527 | -1.0501 | 0.2937 | -0.0496 | ||

| TRS_K* | 4.7486 | 0.4622 | 10.2733 | 0.0000 | 1.4402 | ||

| Cues to Action | SYP_K* | 0.4677 | 0.1725 | 2.7120 | 0.0067 | 0.1812 | |

| TRP_K* | -0.4792 | 0.0924 | -5.1832 | 0.0000 | -0.2015 | ||

| TRS_K* | -0.6067 | 0.1543 | -3.9321 | 0.0001 | -0.2500 | ||

| Trust in Authority | SYP_K* | -3.1964 | 0.4962 | -6.4417 | 0.0000 | -0.5603 | |

| TRP_K* | -0.9933 | 0.2267 | -4.3814 | 0.0000 | -0.1890 | ||

| TRS_K* | 4.6562 | 0.5157 | 9.0282 | 0.0000 | 0.8683 | ||

| Perceived Cost | SYP_K* | 0.7544 | 0.1966 | 3.8362 | 0.0001 | 0.2668 | |

| TRP_K* | 0.5636 | 0.1070 | 5.2686 | 0.0000 | 0.2164 | ||

| TRS_K* | -0.8534 | 0.1785 | -4.7801 | 0.0000 | -0.3211 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).