1. Introduction

The Swiss Personalized Health Network (SPHN) is a national initiative designed to enable FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) [

1] use of health data for research across Switzerland. Within a landscape of diverse technical solutions for clinical data platforms and data standards, SPHN provides the foundation and tooling for data exploration and sharing with a federated infrastructure connecting hospitals and research institutions. Its goal is to make routine clinical data semantically interoperable and computationally accessible for secondary use.

To achieve interoperability, SPHN developed an overarching semantic framework [

2] based on Resource Description Framework (RDF) and clinical terminologies such as the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine - Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) [

3], Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) [

4], Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) [

5], German Modification of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10-GM) [

6] and Swiss Classification of Surgical Interventions (CHOP) [

7]. This framework, implemented through the SPHN RDF Schema, defines a shared vocabulary and structure for representing key healthcare concepts such as diagnoses, laboratory tests, drug administrations, and demographic information. Each participating institution uses the SPHN Connector [

8], a tool to convert local clinical data into standardized RDF according to the SPHN RDF Schema. The resulting semantically enriched and standardized knowledge graphs (KGs) are locally stored in each hospital using a scalable OpenLink Virtuoso RDF triple store [

9] and the data can be shared with researchers in a trusted research environment [

10]. This design ensures that hospitals retain full control over their data while adhering to a common semantic model. The platform provides the technical layer that allows querying these KGs using SPARQL.

The SPHN federated infrastructure comprises the SPHN Federated Clinical Routine Dataset (SPHN FedData) [

11], with data from approximately 800,000 patients and over 12 billion RDF triples. Each individual hospital hosts datasets with up to 2 to 3 billion triples, including approximately 100,000 patients. Despite schema standardization, there is heterogeneity in data completeness, value codings, and population densities across hospitals. For instance, some hospitals use more SNOMED CT than ATC codes and vice versa. There are cases in which different laboratory machines emit different codes for the same type of observation. Another important factor towards data heterogeneity is based on institutions having divergent scopes where codes relevant to children are more present, for instance, in children’s hospitals. The SPHN RDF Schema with the external terminologies provides a composable and semantically consistent framework for representing data. It is designed to have readability, correctness and flexibility following structural patterns such as Event - Test - Result, the explicit separation of Quantity in Value and Unit, or on more complex entities a hierarchical model is applied such as “DrugAdministrationEvent” - “Drug” - “Substance” - “ActiveIngredient”. Additionally, the framework supports historized terminology version (e.g., ICD-10-GM, ATC, CHOP), allowing queries on older but semantically equal codes. Within these considerations, even though query performance is an important factor, it was not the primary goal of the schema as it is to maintain semantic interoperability across heterogeneous data. The integrated RDF data platform uses the SPHN RDF Schema unchanged and does not introduce any read-optimized data model such as having a “HeightMeasurementQuantity” and a “WeightMeasurementQuantity” instead of “Quantity” for both. The advantage is that the schema updates once without requiring to adapt query patterns and user interfaces or re-alignment in general. Querying caching is implemented only on the frontend side. Since most of the SPARQL queries are highly specific and infrequent, the cache offers low benefits. On a very detailed level, Virtuoso offers per table partition which was not offered in other triple store alternatives. An RDFS inference model is built for the global graph and no triples are materialized making Virtuoso the natural choice for our environment setting.

Within this infrastructure, each patient’s data is stored in an individual named graph, and hospitals provide their RDF datasets through SPARQL endpoints backed by scalable Virtuoso deployments. Virtuoso was selected for its open-source nature, Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) transparency, and proven scalability in large, production-grade RDF installations such as UniProt [

12]. It supports RDF quad storage, a key requirement for enabling fine-grained management of patient-level data, including updates and deletions, and offers RDFS reasoning capabilities. In the context of SPHN, a lightweight RDFS inference layer is used to apply minimal but essential RDFS-level reasoning over the global schema and terminology hierarchies. This enables basic RDFS features, such as interpreting subclass and sub property relationships, allowing queries to traverse the ontology structure without requiring full RDFS entailment. Materializing all inferred triples would be infeasible as Virtuoso must execute

rdfs:subClassOf reasoning efficiently at query time.

The size and complexity of SPHN FedData, due to high-cardinality relationships and individual patients having thousands of associated instances, such as >10,000 laboratory results or >50,000 drug administrations, can quickly make SPARQL queries computationally expensive when they are built without a proper execution planning. In this paper, we describe the challenges and optimization strategy for our two key use cases: feasibility queries and value distribution. Feasibility queries compute the number of patients matching a combination of specified clinical, temporal, and logical criteria, whereas value distribution queries characterize cohort-level attributes such as age, sex, or BMI. Both types of queries rely on complex joins across multiple named graphs, hierarchical reasoning, and filtering over high-cardinality relationships, which contributes substantially to computational cost.

To support these use cases, feasibility and value distribution queries follow structured templates and patterns that include:

Temporal relations between instances, particularly events

Boolean operators such as AND, OR, XOR, and NEG

Filters on codes from multiple terminologies, including inference and code versioning

Filters on values and value ranges

Filters on dates and date ranges

Age calculation from BirthDate, with filtering on age or age ranges

Entities such as “DrugAdministrationEvents” and “LabTestEvents”

These patterns define the analytical workload characteristics and set the constraints for SPARQL optimization.

This paper presents methods for optimizing SPARQL queries in this federated healthcare context, with a focus on making feasibility and distribution queries performant across billions of triples in SPHN FedData and different infrastructure setups across hospitals. We explore optimization strategies that leverage query structure, join ordering, selective pattern evaluation, and targeted inference, all while respecting the constraints of the SPHN RDF Schema and the federated infrastructure. By grounding optimization in the real-world use cases, query patterns, and dataset characteristics, we demonstrate how large-scale, heterogeneous clinical RDF datasets can be queried efficiently without compromising semantic interoperability or data governance.

2. Methods

2.1. Requirements

The optimization methods were chosen to address three performance dimensions that are rather uncommon in a homogenous setting:

The slowest datasource needs to be as fast as possible. It is not sufficient if a query is very fast for 5 out of 6 datasources. In the federated approach, the overall query time is constrained by the slowest datasource, even if the remaining datasources perform well.

The runtime variability should be minimized both across queries and datasources. It is not sufficient that very specific queries run fast. Instead, we aim to have repeatable patterns that give predictable runtimes even when changing codes (e.g., queries targeting rare diseases should not be several orders of magnitude slower than equivalent ones on common diseases).

Defined patterns should ensure computability on the platform without running into complexity issues and timeouts where it is usually set to 600 s. To better understand what users, consider acceptable performance, we conducted a survey with 50 potential users, offering runtime options ranging from “<1 minute” to “>24 hours.” Most respondents (66%) selected the option “1–10 minutes”.

The methods can be categorized into three main categories:

Setup of the database environment;

Developing queries and assessing their performance on both mock data and real data of one hospital;

Assessing the queries performance with all participating datasources and iterating.

2.2. Local Database Setup

All participating university hospitals have the same core component to create the data, and the Virtuoso database is set up locally in a comparable manner.

While the content of patient data is heterogeneous across hospitals, some elements are constant:

The SPHN RDF Schema and its terminologies.

The version and configuration of Virtuoso used but scaled to the number of patients.

The data modelling inside the database with the graph partitioning.

The generation of patient RDF data with the SPHN Connector guarantees conformance to the SPHN RDF Schema and a consistent instance of generation.

The infrastructure used to run Virtuoso is comparable among the university hospitals, but the actual size is scaled on the number of patients. The available main memory for the database ranges between 56 GB to 116 GB and the number of available central processing unit (CPU) cores (logical core or thread) is between 7 and 14. While the scaling of the memory ensures that the indices can be held in memory and enough space for aggregate queries is reserved, the CPU scaling is mainly intended to scale the loading speed and satisfy a higher amount of parallel and potentially longer sessions.

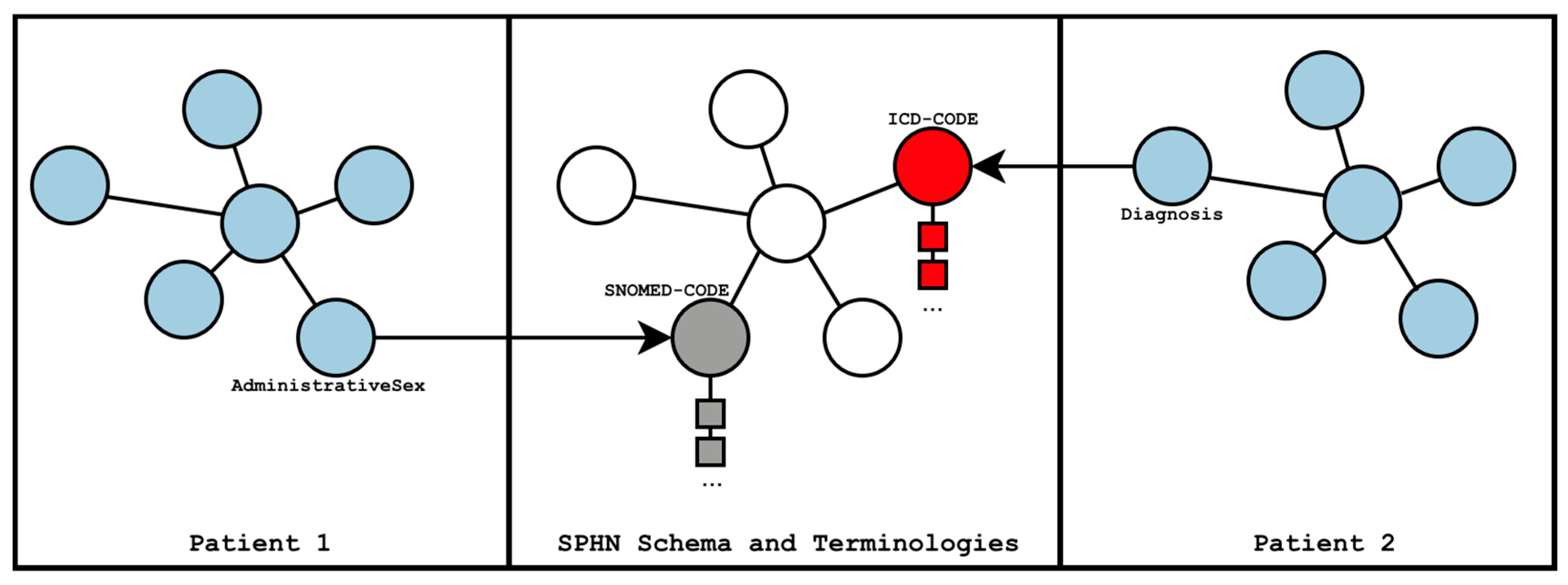

In Virtuoso, every patient is loaded into a separate named graph (see

Figure 1), partitioning individual patient data into a dedicated graph. In addition to the patient graphs, the SPHN RDF Schema and the referenced terminologies are loaded into one separate graph. An RDFS Inference model is built using the SPHN RDF Schema and the terminologies, to support querying of parent classes of codes when the data is annotated with specific

subClassOf codes. For example, a query for icd-10-gm:E11 (i.e., Diabetes mellitus, Type 2) can retrieve all relevant data without specifying all descendant codes such as icd-10-gm:E11.2 (i.e., “Diabetes mellitus, Type 2 with kidney complications”). Virtuoso does not materialize the inferred information in the database but expands it in the model during runtime.

2.3. Performance Testing and Profiling of SPARQL Queries

Our optimization strategies evolved through iterative testing and performance profiling. We first defined reusable query patterns and built SPARQL queries based on these patterns. These queries were initially executed on mock datasets to establish the baseline performance and were subsequently tested on real data at University Hospital of Zurich (USZ), our main partner hospital. Only a few special queries showed suboptimal performance at other sites because of the difference in amount of data or data heterogeneity needed to be further analyzed in all hospitals. To further ensure robustness in our optimization strategy, we developed performance scripts to systematically evaluate the behaviour and runtime of each query type across all sites.

The performance profiling was carried out using the EXPLAIN and PROFILE functionality of the Virtuoso Database [

13]. With this information we were able to assess which access patterns and what order the database planned to use and how effective they were. In some cases, there were differences in the access patterns on mock data compared to real data distributions. Evaluation of the same query on mock data vs real data with query profiling enabled us to study and understand the differences and behaviours of the database on this dataset and use mock data to develop the queries further and without the need to rely on real data at all times and be able to extrapolate whether a query will work on other real data according to the SPHN RDF Schema as well.

As shown in the results (see 3.2.1) the start was using straightforward queries and analyzing their query behaviour. We analyze the behavior of reordering Basic Graph Patterns (BGP), the expansion of SPARQL 1.1 property paths [

14] and the different access paths used through the database. In addition, the PROFILE of a working query indicates the intermediary result of bindings.

A first step chosen to ensure that the order of the BGP is done correctly and in the same manner as we intended to, is to use the ‘sql:select-option “order”’ pragma ([

15]). Using this pragma, the query is executed in the order of appearance, which enables us to overcome the need for deeply nested sub-queries or bad queries where the instantiation of SPHN classes was given precedence. A downside of using this pragma was that the support of the database for optimizing the query order was disabled and the query had to be written in the most optimal way already.

In the process of optimizing the queries, it always has been cross checked whether the queries produce the right result. Sometimes corner cases have been missed which required another approach to the development of the queries and adaptation of the patterns.

After the correctness and performance of the queries in USZ was confirmed, a structured approach to running these queries was developed and the results were captured on the other datasources.

3. Results

3.1. SPARQL Optimization Strategies

Based on hands-on experience and detailed technical profiling, applying optimization techniques significantly improved the performance of SPARQL queries in the SPHN FedData setting. The most significant ones are highlighted below and can be considered as general optimization guidelines.

3.1.1. Leverage Named Graph Partitioning

Each patient’s data resides in its own named subgraph. This structure improves the QUAD pattern execution by allowing the query engine to restrict its evaluation to a specific graph rather than scanning the entire data. This enables efficient per-patient evaluation of eligibility criteria. Because the patient’s subject pseudo identifier is implicit in the named graph, explicit filtering of it is no longer required.

3.1.2. Prioritize Coded Elements

Coded elements (e.g., SNOMED, LOINC) are the most selective components in the data. Query execution should therefore begin with triple patterns involving these codes, forcing the engine to reduce the result space early. SPARQL query plans are manually tuned to enforce this order when automatic optimization fails. The goal of the query plan is to maximize the usage of full indices such as predicate-object-graph-subject (POGS) and predicate-subject-object-graph (PSOG), as well as partial indices with filter pushdown, to reduce the amount of data processed. Moreover, since the SPHN schema contains a lot of codes, there is no realistic use case for querying textual fields.

3.1.3. Avoid Expensive Constructs

Knowing the approximate cardinalities in the data helps in the query design process that operates from entities with smaller upper-bound result sets. This reduces the search space right from the beginning and prevents constructs that would otherwise generate very large intermediate results. For example, if a hospital has around 200,000 patients but 10 million Drug Administration Events, starting the query from patients instead of the drug administration significantly limits the search space.

Where possible:

Avoid OPTIONAL; instead, split queries and use UNION.

Avoid DISTINCT and GROUP BY on large, unfiltered sets.

Avoid multiple unrelated BGPs lacking a common patient identifier.

Replace SPARQL 1.1 property paths with explicit property chains.

Use the identity filter (comparison to all patients) only when explicitly required (e.g., for the NOT filter).

Avoid SPARQL 1.1 paths, as they are often evaluated back to front, which is not the intended order.

3.1.4. Precompute and Reuse

Augmented entities (e.g., “DrugAdministrationEvent”, “LabTestEvent)” and computed values (e.g., hasCalculatedBirthDate) are used to reduce triple traversal depth and improve consistency across hospitals. Relying on such precomputed structures improves query execution while ensuring that the derived values retain their semantic meaning.

3.1.5. Optimize Aggregate and Specialized Queries

When queries require the use of MIN, MAX, AVG, or concept counts, the aggregation should be pushed as close as possible to the datasource to reduce generating intermediate results.

3.2. Example of a Query Optimized Process

To illustrate the query optimization process, we present a representative feasibility query that counts patients with a specific billed diagnosis (coded with ICD-10-GM E11 Type 2 diabetes mellitus) and an administrative sex (coded with SNOMED CT 248152002 female). During the optimization process, the iteratively built queries were tested locally using mock data, followed by execution on real data in the USZ environment.

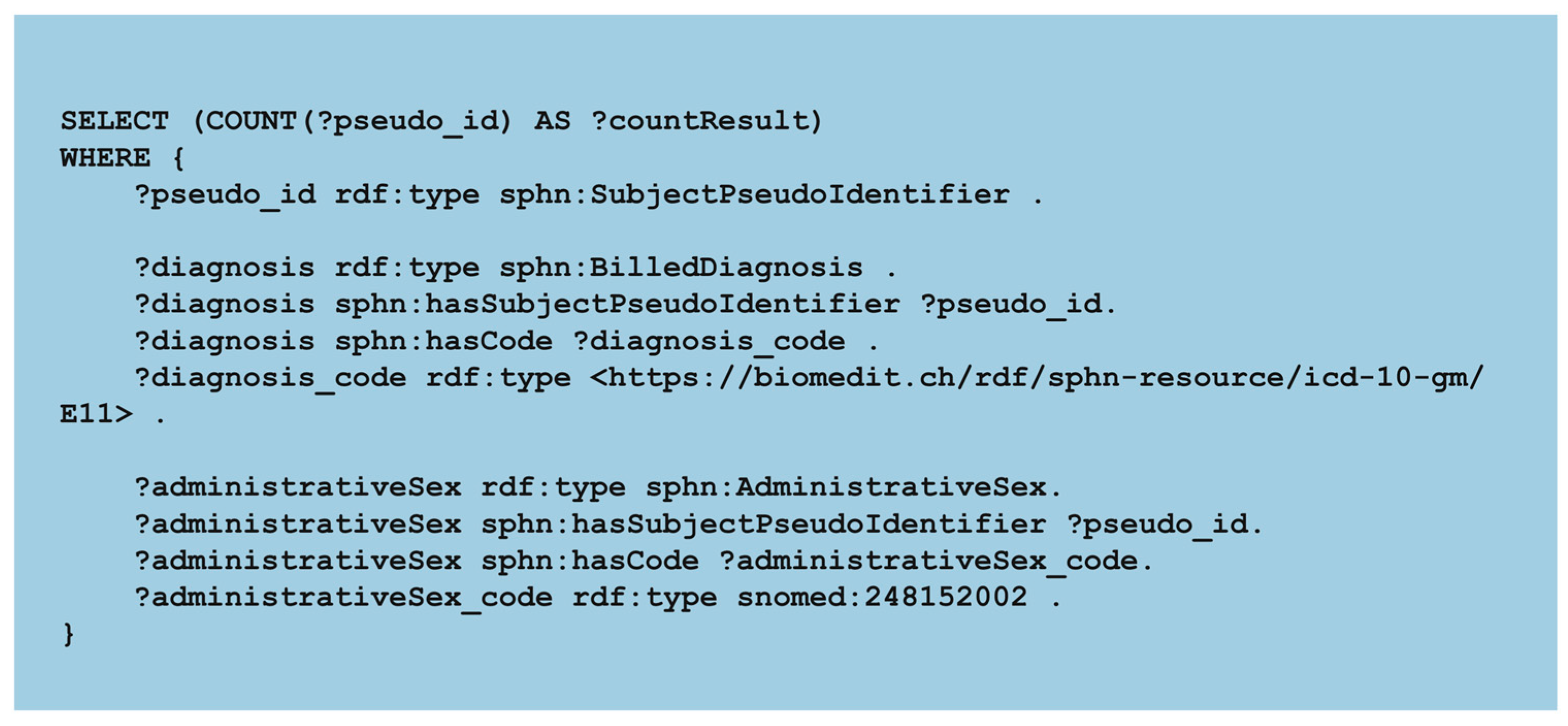

3.2.1. Starting Query

The starting query expresses both conditions over the full graph and relies on the Virtuoso optimizer for doing the join operation. It also filters the patient over the “rdf:type” filtering. As a result, the query goes into timeout with large intermediate result sets. When running the query without timeout constraints, even after 3 hours no result was returned. The patterns “sphn:BilledDiagnosis” and “sphn:AdministrativeSex” are expanded before applying the filtering conditions.

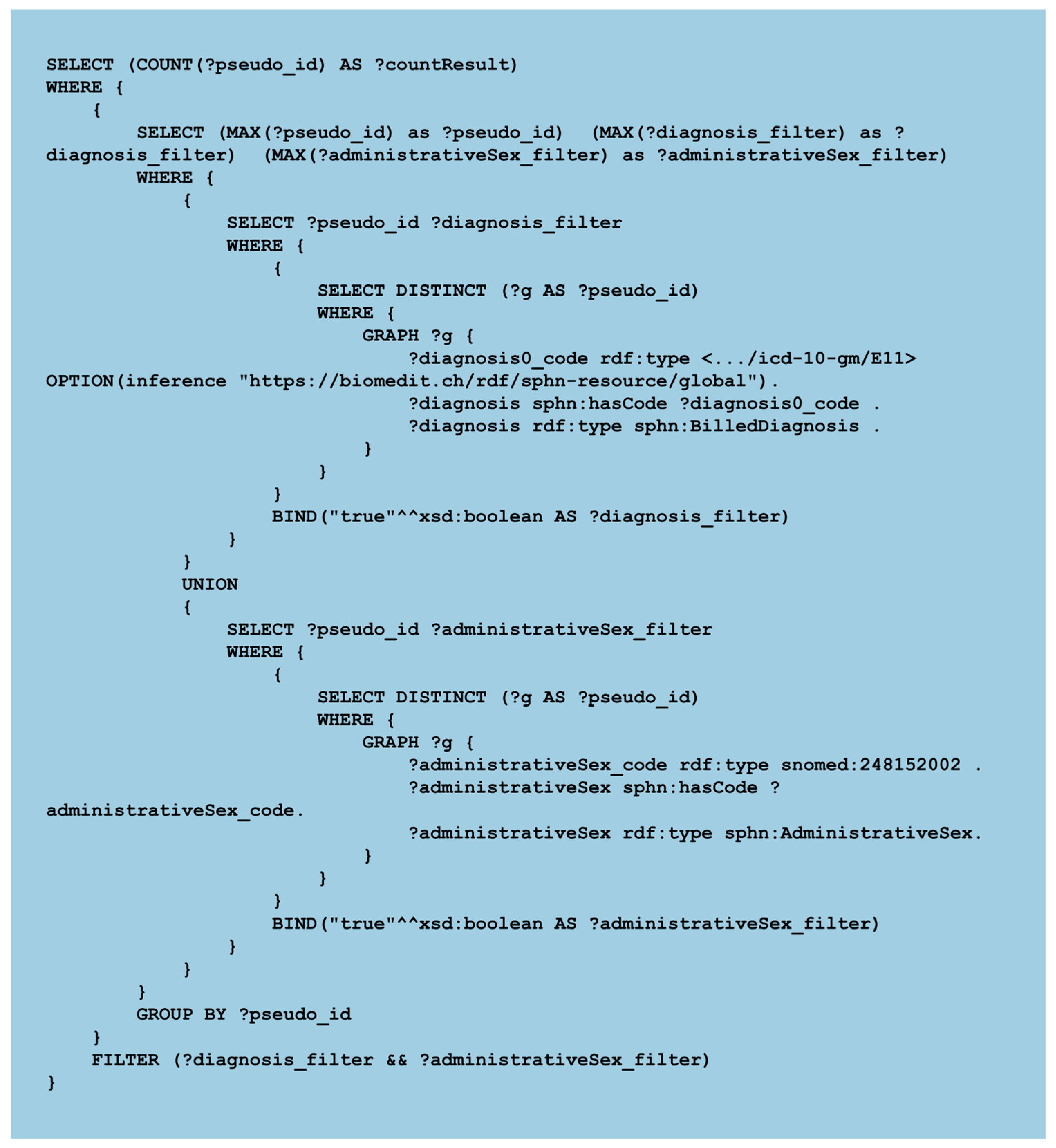

3.2.2. Step A

In the first optimized version, the execution is explicitly constrained to the patient named graphs instead of filtering the type “SubjectPseudoIdentifier”. This ensures that only relevant subgraphs are scanned, preventing global expansion across all patients and each condition is evaluated in its own subquery reducing the intermediate results. The “UNION” operator is used to combine the results and apply the filter on it for the presence of Diagnosis and AdministrativeSex. Additionally, we disallow BGP reordering by the Virtuoso optimizer using the sql:select-option “order”. Query at step A was stopped after 3 h. (

https://git.dcc.sib.swiss/sphn-semantic-framework/outreach/sparql-optimization/-/blob/main/Example_queries/StepA.rq).

3.2.6. Execution Time

The primary goal is to reduce the execution time after iterative query optimization, as shown in

Table 1. The starting query and the first “optimization” (Step A) were both terminated after 3 h.. From Step B, the second optimization, the processing time decreased to ~40 s to finally reach less than 1 s on the fourth optimization (Step D).

3.3. Validation of Query Patterns Across Multiple Hospitals

The proposed SPARQL optimization strategies address key performance challenges in federated cohort queries. The performance was evaluated using a set of feasibility and distribution SPARQL queries, first executed at USZ, with end-to-end runtime measured in seconds, including the result of transmission. After identifying a set of performant queries, we validated them using a dedicated performance notebook executed at all hospitals (see

Table 2. for feasibility queries and

Table 3. for distribution queries). This benchmarking approach enabled us to assess overall performance across sites, highlight remaining gaps, and identify queries requiring further optimization.

Overall, most feasibility queries executed within seconds at all hospitals. The only notable exception was the Lab value restriction query, which showed substantially slower execution at one hospital (discussed in the Discussion section). Importantly, even the more computationally intensive distribution queries executed well below our target of 10 minutes across all sites.

4. Discussion

The optimization strategies demonstrate how query performance can be improved, as demonstrated in the SPHN FedData setting. While some behaviours of the Virtuoso optimizer may limit performance, we must consider other aspects such as the scale, heterogeneity of the data population and the lack of specific statistics to guide preference in terms of BGP and knowledge of the “Schema”. Equally important is the SPHN RDF Schema, which is semantically correct and highly reusable, but not specifically designed for low-latency analytical querying. Introducing more dedicated classes (e.g., make a “HeightMeasurementQuantity” and a “WeightMeasurementQuantity”) would help the optimizer to find the right element much faster. Since the SPHN RDF Schema was defined to be implementation agnostic and is continuously evolving aiming to be general and stable, introducing read-optimized schema is not suitable. Thus, the approach focuses on query side optimization to preserve semantic interoperability and schema stability while still having performant feasibility and distribution analysis queries. The optimization strategies can be further improved by introducing defined assumptions. For instance, the optimized query at step D can be further improved by reducing the evaluated search space to the minimum for the clinical conditions. Instead of traversing the full “BilledDiagnosis” or “AdministrativeSex”, the query now targets only the most selective code elements. Specifically, ICD-10-GM code E11 can only occur in “Diagnosis” context, and the SNOMED code 248152002 can only be “AdministrativeSex” already implying the surrounding class structure without the need to traverse the full path. This query version (not introduced in the results section as it remains experimental) runs in 0.48s, hence reducing the runtime to half of the result observed in step D.

In some queries, such as the “Lab value restriction” and the “Lab value restriction++” (including Age and Sex distribution of the resulting patient cohort) there is still a large variety in the runtime of this query. This was analyzed in detail and tracked down to the different style of modelling the data. In this case, the Internationalized Resource Identifiers (IRI) on the “LabResult” instances were reassigned to different patients. Which results in a sub-optimal performance on these queries. We are investigating different strategies to further optimize our queries including testing further query patterns, expanding the compute capacity of infrastructure or change the IRI generation pattern.

5. Conclusion

This work presents an approach for optimizing SPARQL queries over large, interconnected, and federated clinical RDF datasets, in the context of the Swiss Personalized Health Network. Using key structural characteristics such as patient-level named graph partitioning, coded clinical terminologies, and lightweight inference, we developed and validated a set of practical optimization strategies to improve query performance for feasibility and distribution analyses. Our results show that careful query planning can avoid building costly constructs and reduce execution times by several orders of magnitude. The strategies were validated across all participating hospitals, demonstrating that performance challenges in complex and semantically driven data infrastructures can be addressed at the query level, without required changes to the underlying data schema. While SPARQL is not a bottleneck, it is true that efficiency in a semantically rich environment depends on designing queries on what is not known to the database. The SPHN RDF Schema is intentionally general supporting interoperability, and it is not read-optimized. Likewise, the triple store lacks specific statistics such as code cardinalities that would normally guide the optimization. Because the system cannot make these assumptions, queries can still be optimized following the presented strategies making queries a lot faster as shown in the example.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and Institutional Review Board (IRB) review were not required for this study because only query run times and aggregated patient counts, and no identifiable patient-level information was shared outside the hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank teams in hospitals involved with the iterative testing of the query performances, especially Yves Jaggi, Jesus Fernandez, Xeni Deligianni, Maren Diepenbruck, Luca Leuenberger, Pedram Bürgin, Janshah VeettuvalappilIkbal, Klaas Kreller, Helena Peic Tukuljac, Abdel Zalmate, Mathias Gassner, Jan Armida, Rita Achermann, Marouan Borja.

Funding

This work was funded by the State Secretariat for Education, Research, and Innovation (SERI) via SPHN.

Declaration on Generative AI

During the preparation of this work, the authors used GPT-4 to fix formulations, grammar, and spelling checks. After using these services, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the publication’s content.

References

- Lawrence, A.K.; Selter, L.; Frey, U. SPHN - The Swiss Personalized Health Network Initiative. Stud Health Technol Inform 2020, 270, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touré, V.; et al. FAIRification of health-related data using semantic web technologies in the Swiss Personalized Health Network. Scientific Data 2023, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, T.; Grieve, G. SNOMED CT,” pp. 155–172, 2016. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.J.; et al. LOINC, a universal standard for identifying laboratory observations: a 5-year update. Clin Chem 2003, 49, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- “ATCDDD - Home.” Accessed: Dec. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://atcddd.fhi.no/.

- “BfArM - ICD-10-GM.” Accessed: Dec. 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.bfarm.de/EN/Code-systems/Classifications/ICD/ICD-10-GM/_node.html.

- “Schweizerische Operationsklassifikation (CHOP) - Systematisches Verzeichnis - Version 2025 | Publikation.” Accessed: Dec. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/gesundheit/nomenklaturen/medkk/instrumente-medizinische-kodierung.assetdetail.32128591.html.

- Touré, V.; et al. SPHN Connector - A scalable pipeline for generating validated knowledge graphs from federated and semantically enriched health data,” Nov. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Erling, O. Virtuoso, a Hybrid RDBMS/Graph Column Store,” IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin, 2012.

- Schmid, D.C.; et al. SPHN - The BioMedIT Network: A Secure IT Platform for Research with Sensitive Human Data. Stud Health Technol Inform 2020, 270, 1170–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armida, J.; et al. Semantic Interoperability at National Scale: The SPHN Federated Clinical Routine Dataset,” Dec. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.; et al. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D609–D617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “Chapter 6. Administration.” Accessed: Dec. 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://docs.openlinksw.com/virtuoso/ch-server/#perfdiagqueryplans.

- “SPARQL 1.1 Property Paths.” Accessed: Dec. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.w3.org/TR/sparql11-property-paths/.

- “16.17.5. Erroneous Cost Estimates and Explicit Join Order.” Accessed: Dec. 02, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://docs.openlinksw.com/virtuoso/rdfperfcost/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).