Introduction

In the current digital era, Artificial Intelligence (AI) can enhance the provision of healthcare and other services that promote human health and well-being. AI can help to enhance disease diagnosis, develop personalised healthcare systems, and aid clinicians in decision-making (Price 2019). AI algorithms are trained on large datasets to learn hidden patterns from real-world instances, based on which they make informed decisions (Alowais et al. 2023). In healthcare, most disease diagnoses are typically made by manually examining patient reports or scans. This process is tedious, time-consuming, and prone to human error (Saba 2020). AI, with its abilities to process large amounts of data, can be used to automate clinical tasks that enable rapid disease diagnosis, efficient treatment delivery, and help reduce healthcare costs as well (Kumar et al., 2022).

Despite all these advancements, AI algorithms still have some limitations, including the lack of generalisability, such that models trained on a specific dataset might not perform the same way in different conditions or when used on other datasets, and the issue of privacy preservation, especially when dealing with healthcare data (Team, 2024). Also, patient data is highly sensitive in nature, due to which different regulations, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), prohibit the sharing of such information to protect the privacy of patients and medical information. While such protections are necessary, these measures may lead to medical data scarcity by making data inaccessible (Sufi 2024). Therefore, the available real-world medical datasets are usually small in size or imbalanced, i.e., they do not well represent different classes, ethnicities, genders, and races (Hameed et al. 2024, Mehmood Qureshi et al. 2024). AI models trained on such datasets will inherit and replicate those shortcomings in their decisions (Mehrabi et al. 2021). These models usually favour the majority group or class and provide ill-suited recommendations for minority or the least represented groups (Qureshi et al. 2026).

Since real-world medical data is scarce and not readily available to the large research community, one solution to this problem is the generation of synthetic or artificial data (Ali et al. 2023, Mittermaier et al. 2023). Synthetic data generation can be defined as the generation of artificial data that is statistically similar to real-world data (Hradec et al. 2022). As synthetic data is generated, it minimises the risk of revealing sensitive information (Hradec et al. 2022). Also, it increases the data volume, improves data accessibility, and introduces diversity in the datasets (Pezoulas et al. 2024).

Motivation

The inclusion of AI in the health industry can help in various clinical activities, including disease diagnosis, treatment planning, drug discovery, and many more (Hajizadeh, 2024). To build effective AI models, large training datasets that are well-represented of all possible scenarios, groups, and communities are required (Ashik

et al. 2024). As large and diverse medical datasets are not easily accessible, synthetic data generation provides a potential solution to mitigate imbalance, increase data volume, and introduce diversity in the existing datasets (Hameed

et al. 2024). Most disease diagnoses in the medical field are made by analysing a broad spectrum of medical imaging, such as Computed Tomography (CT), ultrasound, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), etc (Aamir

et al. 2024). Therefore, this paper explores different synthetic image generation techniques, highlighting opportunities and challenges. The formulated hypothesis and related research questions are as follows:

Hypothesis: Synthetic data can help improve medical image datasets by generating samples that enhance diversity, address imbalances, and increase dataset volume.

RQ1: What are the different techniques used to generate synthetic medical images?

RQ2: What are the challenges of the techniques used to generate synthetic data?

Search Methodology

To identify recent research articles in the field of synthetic medical image generation, we searched various databases, including Science Direct, IEEEXplore, Google Scholar, ACM Digital Library, and Springer. To query these databases, we formulated the following research query that consists of keywords: ((Synthetic OR Artificial) AND (Artificial Intelligence OR Deep Learning OR Machine Learning) AND (image OR scans OR medical image)). To identify recent and relevant studies, we devised the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

Research articles that discuss synthetic image generation or synthetic data employed in the medical field.

Research studies published between 2021 and 2025.

Research articles published in journals, conferences, or proceedings and written in English were included.

Exclusion Criteria

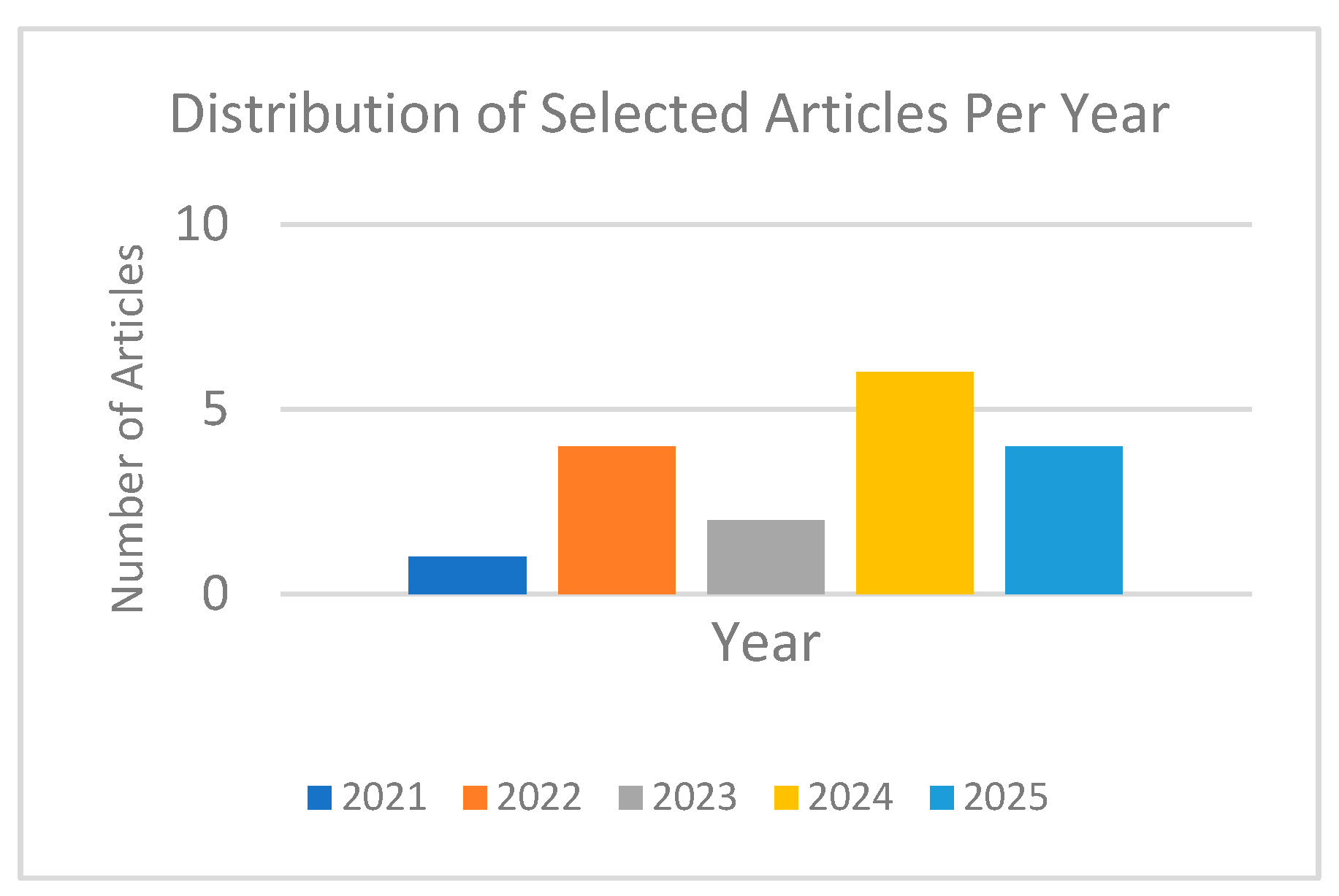

The initial searches result in 2,360,000 articles. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, the number was reduced to 18,100 papers. Based on the title and abstract relevancy, we selected 56 articles. Finally, 17 research articles were selected after being thoroughly assessed through full article reading.

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the selected research articles over the years.

Synthetic Medical Image Generation

Table 1 shows an overview of different synthetic image data generation techniques, the dataset used, and the evaluation metrics used in selected studies. Deep Learning (DL) models are the most commonly used techniques, with a large number of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and their proposed variants.

Techniques for Synthetic Image Generation

With the improved computational capabilities, DL architectures with their deep neural networks have transformed image processing and computer vision

industry (Zulfiqar et al. 2024). These deep architectures have significantly improved the image generation capabilities of the computer, which are helpful to mitigate imbalances and increase the volume of datasets used for AI model training.

This section discusses the synthetic data generation techniques in detail. To enhance readability, we have organised these techniques into two subsections: the first focuses on Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) and its variants, followed by a second subsection covering other approaches.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

GANs are most commonly used for synthetic image data generation. A GAN architecture consists of two neural network architectures: the generator and the discriminator, as shown in

Figure 2. The generator is responsible for generating synthetic data that looks real, and the discriminator tries to identify if the image is real or synthetic. These two models are trained to reduce the difference between generated and real data (Goodfellow

et al. 2014).

To improve the quality of image data generated by GAN and to overcome limitations such as vanishing gradients, sensitivity to hyperparameters, mode collapse, and training instability, various variants of GAN have been proposed in the literature. Some of these recent variants are discussed in detail below:

SinGAN-seg

SinGAN-Seg is a GAN variant that generates synthetic images and their segmentation mask, which is a pixel map that shows anatomical regions of the image with only a single training image. SinGAN-seg helps improve performance when only limited data is available, unlike traditional GANs, which need large datasets for training. It usually takes a single image as input, learns its internal distribution, including textures, scale, shape, and structures, and then generates new variations with changes in distribution (Thambawita et al.,2022).

A study by (Thambawita et al. 2022) is focused on SinGAN-seg, which was trained on the Hyperkvasir dataset. This dataset consists of endoscopic images of the gastrointestinal tract and their polyp segmentation masks. The results showed that the accuracy score on generated data is very close to that trained on real data. However, the data generated by this technique is not diverse since it uses one image to generate synthetic data.

DCGAN

Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN) uses convolutional layers to improve the image generation process. A random noise with n dimensions is given as input to the generator, which is passed through convolutional layers, increasing the spatial resolution until a fake image is generated. The generated image is then passed onto a discriminator, which also consists of convolutional layers, to label it as real or a fake image (Heenaye-Mamode Khan et al. 2022). DCGAN can generate high-quality images compared to traditional GANs (Ali et al. 2024).

The study (Vipul Arya and Sathya 2025) has employed DCGAN to generate synthetic images trained on a dataset named Coronary CT Angiography, which consists of coronary artery images of 500 patients, 250 patients of positive cases and 250 patients of negative cases. A pretrained model called MobileNet was used for classifications. The original and synthetic data are divided into six subsets: Full Data Negative (FDN), Full Data Positive (FDP), High-Confidence Data Negative (HCDN), High-Confidence Data Positive (HCDP), Low-Confidence Data Negative (LCDN), and Low-Confidence Data Positive (LCDP). The DCGAN model achieved a maximum accuracy of 92% and FID scores as low as 7.8, especially in FDN and FDP. The low confidence dataset gave a low accuracy of 79% with an FID of 25.2 for LCDP. DCGAN helps in preserving the properties of real images. However, this technique is computationally very expensive, as it takes about 4 to 7 hours for training.

In another study by (Heenaye-Mamode Khan et al. 2022) DCGAN was used to address the limitation of the inaccessibility of annotated data sets in dermatology. They used a dataset of 13,650 images to classify 15 types of skin diseases, utilizing both labelled and unlabelled images. DCGAN uses the generator and discriminator with 4 convolutional layers in each. The DCGAN outperforms the traditional data augmentation method by achieving an accuracy score of 92.3% on labelled data and 91.1% on unlabelled data. DCGAN shows promising results in the classification of skin conditions; however, it lacks expert validation of the model.

cGAN

Conditional GAN or cGAN is a variant of GAN in which the discriminator and generator are conditioned on some information, such as a class label. In cGAN, random noise, along with the condition, is given as input to the generator. The synthetic images will be generated based on labels and conditions. These generated images are passed onto the discriminator trained on real images and their corresponding labels that classify the newly generated images as real or fake. cGAN is one of the best among basic GAN architectures because it can learn specific features from the input data via conditional information that improves the feature details in generation (Makhlouf et al. 2023).

The study (Waisberg et al. 2025) have reviewed generative AI techniques in ophthalmology. While discussing the utility of cGAN, the study reported the use of cGAN for the generation of retinal fundus images (images of the interior surface of the eye) to train a Deep CNN algorithm for the diagnosis of exudate in retinal fundus images. The results show an improvement in model generalisation and network robustness when trained on synthetic data. Another study investigates the potential of cGANs in the generation of synthetic images. Based on cGAN, two new models named Enhancement and Segmentation GAN (ESGAN) and Enhancement GAN (EnhGAN) are proposed. In ESGAN, classifier loss is combined with adversarial loss to predict input patch labels, and EnhGAN is used to generate high-contrast images. ESGAN and EnhGAN are tested on publicly available BraTS 2013 and 2018 datasets, consisting of 3D Brain MRI scans. The results showed that the use of synthetic data improved the segmentation performance as compared to other state-of-the-art techniques (Hamghalam and Simpson 2024).

Pix2pix

Pix2pix is another variant of the cGAN designed for image-to-image translation. Like cGAN, Pix2pix output is also conditioned on an input image. This technique has demonstrated capabilities on a variety of image-to-image translation tasks, such as converting maps to satellite images and changing black and white images into coloured ones, etc (Brownlee, 2021). A study by (Vadisetty et al. 2024) used Pix2Pix for the segmentation of pulmonary abnormalities using chest X-rays. They used the Montgomery dataset for model training, and then the Shenzhen dataset was used for validation. Different data augmentation techniques, such as rotation, shifting, shearing, and horizontal flipping, were used to introduce diversity in the dataset. The model achieved an accuracy score of 95.87% on the Shenzhen dataset, outperforming other techniques.

SPADE GAN

Spatially Adaptive Denormalisation GAN (SPADE GAN) is an improved variant of the pix2pix technique, which is specifically developed for semantic image synthesis. The most important part of SPADE GAN is the use of SPADE layers, which are conditional normalisation layers that propagate semantic information throughout the network. The results from SPADE GAN show that the proposed technique produced high-quality images that better preserve semantic information (Park et al. 2019). Moreover, the comparison of different GAN variants for generating synthetic images shows that the output from SPADE GAN was comparable to real-world images; however, the training time is very long, such that it can take up to 10 days per dataset (Skandarani et al., 2023).

StyleGAN

StyleGAN is designed to offer a more controlled image generation process. The generator of StyleGAN includes an Adaptive Instance Normalisation (AdaIN) block. It uses an 8-layer Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) mapping function on the input latent vector, and the noise is injected at every level of the network. The generated image quality improved considerably (Karras et al. 2019). The comparison of Style GAN, as demonstrated by (Skandarani et al., 2023) shows that synthetic images generated by Style GAN were visually very similar to the original dataset, such that the accuracy of manual classification performed by experts to differentiate real and generated images was recorded to be 60%. However, StyleGAN has a long training time; it can take up to 30 days to train on a dataset.

LSGAN

Least Squares GAN (LSGANs) are a variant of GAN that can generate better quality images as compared to traditional GANs and has stable performance during the learning process. The difference between LSGAN and a traditional GAN is that in a traditional GAN, the discriminator uses a sigmoid cross-entropy loss, which suffers from the problem of vanishing gradients, which makes the learning process of the model very slow, and it also prevents the model from improving its performance. LSGAN addresses this issue by using a least squares loss function, which makes the learning process more stable and generates high-quality outputs (Mao et al. 2017). In a study, LSGAN is used to generate synthetic images trained and tested on three datasets: ACDC, a cardiac cine-MRI; IDRiD, a retinal fundus image dataset; and SLiver07, a liver CT dataset. After training, the model generated 10,000 synthetic images for each dataset; these synthetic images were used to train a U-Net to evaluate the semantic segmentation. The results showed that LSGAN was much more sensitive to hyperparameters and did not perform well when compared to StyleGAN and SPADEGAN, despite intensive hyperparameter tuning (Skandarani et al., 2023).

WGAN

Wasserstein GAN (WGAN) is developed to improve model learning stability, hyperparameter searches, and vanishing gradients etc. The loss function of traditional GANs uses the Jensen-Shannon divergence, which results in unreliable gradients when the real and generated data lie on low-dimensional manifolds. WGAN overcame this issue by replacing the Jensen-Shannon divergence with the Wasserstein Earth Mover distance, thus reducing mode collapse and stabilising the learning process (Arjovsky et al. 2017). The comparison of GAN variants by training them on 3 datasets shows that WGAN has more stable and consistent training than LSGAN; however, it is still not considered as very effective compared to advanced models (Skandarani et al. 2023).

Geometric GAN

The Geometric GAN is another variant of GAN that aims to ease the optimisation process by converging to the Nash equilibrium between the generator and discriminator. It divides the GAN training into three geometric steps, i.e., separating SVM hyperplane search, discriminator parameter update, and generator update. The discriminator learns how to separate real and generated images using a separating hyperplane with a maximal margin between classes. The generator then learns to generate data that looks similar to the real distribution. The mode collapse reduces with the Geometric GAN, and the training becomes more stable (Lim and Ye 2017, Skandarani et al. 2023).

Other Techniques

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

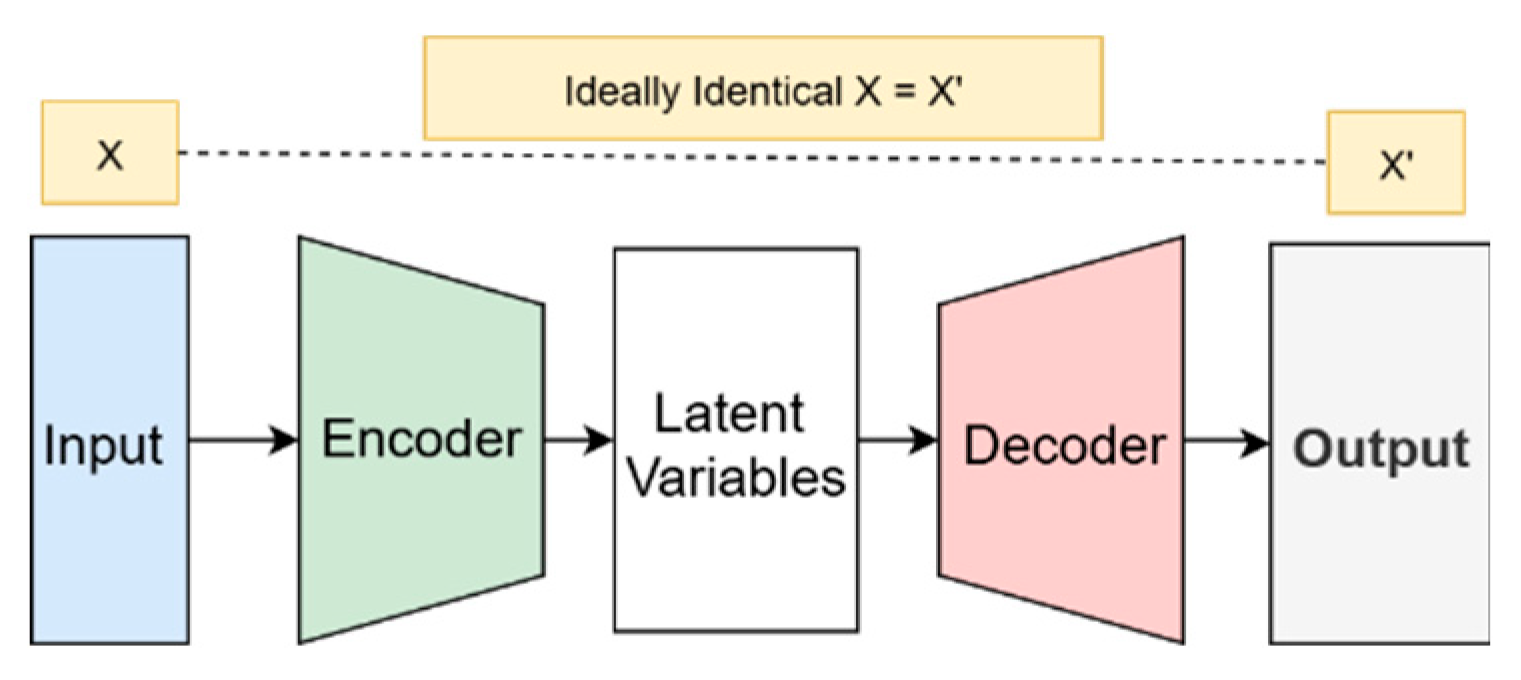

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), as shown in

Figure 3, are also a DL technique for generating synthetic data. The architecture of VAEs consists of an encoder and decoder. The encoders map the input data into a latent space, a compressed representation of data, producing mean and standard deviation vectors. The decoder reconstructs a synthetic image by decoding the latent space (Huang

et al. 2018, Diamantis

et al. 2022). The training of VAEs is fast due to backpropagation (Doersch 2016).

In a study by (Diamantis et al. 2022) VAEs are used to generate endoscopic images called Endoscopic VAE (EndoVAE). This study aims to use synthetic images as a substitute for real images in order to preserve privacy. To generate synthetic images, a publicly available KID dataset consisting of 2371 images of different parts of the gastrointestinal tract, with 728 normal cases and 227 abnormal cases, is used. To assess the generated images, a classifier is trained on both generated and real images. The classifier achieved an Area Under Curve (AUC) of 81.9% on synthetic images, comparable to the AUC of 90.9% achieved on real images. This technique surpassed GAN, which has achieved an AUC score of 79.2%. However, the quality of the generated image is compromised due to blurriness and lower resolution, and colour inconsistency.

Diffusion Models

Diffusion models are generative models inspired by non-equilibrium thermodynamics. Diffusion models consist of two steps. In the first step, noise is gradually added to the input data, and then the model learns to eliminate the noise, generating synthetic data starting from noisy inputs (Pozzi et al. 2024). A study by (Pozzi et al., 2024) focused on diffusion models and, more particularly, the Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM). In this study, the author used 648 whole slide images from the Genotype Tissue Expression (GTEx) dataset. The diffusion model was trained in 215,000 steps, and it generated 3,001 synthetic images per tissue. Diffusion models take longer to generate synthetic images as compared to GAN architectures.

Discussion

The findings from the literature review suggest that synthetic image generation techniques can produce images that look similar to real-world data. The performance of the classifiers improved when synthetic data was used in conjunction with real data, and the evaluation metric scores remained comparable even when real-world data was entirely replaced with synthetic data (Diamantis et al. 2022, Heenaye-Mamode Khan et al. 2022). Therefore, we fail to reject our hypothesis stating that synthetic data can help improve medical image datasets by generating samples that enhance diversity, address imbalances, and increase dataset volume. The corresponding research questions are answered below:

RQ1. What are the different techniques used to generate synthetic medical images?

DL techniques have progressed rapidly in the field of artificial data generation. Different image generation techniques are discussed in this paper. GAN is one of the most commonly used techniques. There are various variants of GAN proposed in the literature to optimise the working of traditional GAN architecture to improve the quality of generated data. These variants include SinGAN-seg (Thambawita et al. 2022), DCGAN (Heenaye-Mamode Khan et al. 2022), cGAN, LSGAN, Geometric GAN and WGAN. Apart from GANs, Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are another DL technique that mainly consists of an encoder and decoder to generate synthetic data. Furthermore, diffusion models generate synthetic data by adding noise to input data and then reversing the process. 3D simulation tools are also used to generate 3D simulations of images using different software.

RQ2. What are the challenges of the techniques used to generate synthetic data?

There are several limitations of data generation techniques discussed below:

Lack of effective evaluation metrics: All these techniques employed different evaluation metrics, which shows the absence of effective metrics that make the performance comparison of different generative models difficult (Rujas et al. 2025). Also, the existing metrics do not capture visual quality, which is usually evaluated manually by human experts (Ali et al. 2025).

Lack of Explainability: DL architectures consist of neural networks that lack explainability, and medical domain experts find it very difficult to understand the output of models and how the data is being generated.

Mode Collapse: Another limitation highlighted most often is the mode collapse, where the generator ignores the data distribution and can only produce limited outputs, which decreases the model’s performance as well as diversity in the dataset (Chen et al. 2022, Kapania et al. 2025).

Training Instability: Due to the adversarial nature of GAN, the stable convergence of the model is a challenging task.

Limited training datasets: One of the key challenges in the field of synthetic image generation is the small size of datasets used for training models. Low-quality training images depreciate the performance of the model, which may lead to poor generalisation and biased models (Altalib et al., 2025b).

High computational cost: The computational cost of DL techniques is very high. For example, SPADE GAN take days for its training (Skandarani et al. 2023). Other than intensive computational resource requirements, they also generate excessive heat, which is harmful to the environment.

Conclusion & future work

This paper reviews synthetic image generation techniques, particularly focusing on the medical domain. For this purpose, we have searched different databases. A total of 17 articles are reviewed for their technique, dataset, evaluation metric, and limitations. The findings of the review show that synthetic data generation techniques have the capability to generate realistic data that improves the quality of existing datasets as well performance of the AI models trained on them. GAN is the most commonly used DL technique. There are various variants of GAN proposed in the literature to address the limitations of the traditional GAN. Other than that, VAE, diffusion models and 3D simulation are also used for medical image generation. The limitations of these techniques include limited training datasets, model collapse, vanishing gradient, lack of explainability and training instability of DL architectures. Efforts are underway to address these challenges to fully realise the potential of AI in the healthcare domain. In future, we will extend our review to other databases to increase the scope of this study. Also, we will include synthetic data generation techniques for other data modalities to provide broader coverage and enhance the findings of this study.

Acknowledgments

This research was managed by the CREATE-DkIT project, supported by the HEA’s TU-Rise programme and co-financed by the Government of Ireland and the European Union through the ERDF Southern, Eastern Midland Regional Programme 2021-27 and the Northern Western Regional Programme 2021-27. This research is also partially supported by the Research Ireland under Grant Number 21/FFP-A/9255.

References

- Aamir, A., Iqbal, A., Jawed, F., Ashfaque, F., Hafsa, H., Anas, Z., Oduoye, M.O., Basit, A., Ahmed, S., Abdul Rauf, S., Khan, M., and Mansoor, T., 2024. Exploring the current and prospective role of artificial intelligence in disease diagnosis. Annals of Medicine & Surgery, 86 (2), 943–949. [CrossRef]

- Abufadda, M. and Mansour, K., 2021. A survey of synthetic data generation for machine learning. 2021 22nd International Arab Conference on Information Technology, ACIT 2021.

- Ali, H., Grönlund, C., and Shah, Z., 2023. Leveraging GANs for Data Scarcity of COVID-19: Beyond the Hype.

- Ali, M., Ali, M., Hussain, M., and Koundal, D., 2025. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for Medical Image Processing: Recent Advancements. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 32 (2), 1185–1198. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., Ali, M., and Javed, M., 2024. DCGAN for Synthetic Data Augmentation of Cervical Cancer for Improved Cervical Cancer Classification. 2024 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science, SCEECS 2024.

- Alowais, S.A., Alghamdi, S.S., Alsuhebany, N., Alqahtani, T., Alshaya, A.I., Almohareb, S.N., Aldairem, A., Alrashed, M., Bin Saleh, K., Badreldin, H.A., Al Yami, M.S., Al Harbi, S., and Albekairy, A.M., 2023. Revolutionizing healthcare: the role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Medical Education 2023 23:1, 23 (1), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, H., Kavakli-Thorne, M., and Kumar, G., 2021. Applications of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): An Updated Review. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 28 (2), 525–552. [CrossRef]

- Altalib, A., McGregor, S., Li, C., and Perelli, A., 2025. Synthetic CT Image Generation From CBCT: A Systematic Review. IEEE Transactions on Radiation and Plasma Medical Sciences, 1–1.

- Arjovsky, M., Chintala, S., and Bottou, L., 2017. Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Networks.

- Ashik, M., Hameed, S., Mehmood Qureshi, A., and Kaushik, A., 2024. Mitigating Bias in Medical Datasets: A Comparative Analysis of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) Based Data Generation Techniques ⋆.

- Brownlee, J., 2021. How to Develop a Pix2Pix GAN for Image-to-Image Translation. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from https://machinelearningmastery.com/how-to-develop-a-pix2pix-gan-for-image-to-image-translation/.

- Chen, Y., Yang, X.H., Wei, Z., Heidari, A.A., Zheng, N., Li, Z., Chen, H., Hu, H., Zhou, Q., and Guan, Q., 2022. Generative Adversarial Networks in Medical Image augmentation: A review. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 144, 105382. [CrossRef]

- Diamantis, D.E., Gatoula, P., and Iakovidis, D.K., 2022. EndoVAE: Generating Endoscopic Images with a Variational Autoencoder. IVMSP 2022 - 2022 IEEE 14th Image, Video, and Multidimensional Signal Processing Workshop.

- Doersch, C., 2016. Tutorial on Variational Autoencoders.

- Goodfellow, I.J., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., Courville, A., and Bengio, Y., 2014. Generative Adversarial Nets. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 27.

- Hajizadeh, A., 2024. How AI Is Helping Doctors Make Better Decisions in Healthcare. Communications of the ACM. Retrieved July 28, 2025, from https://cacm.acm.org/blogcacm/how-ai-is-helping-doctors-make-better-decisions-in-healthcare/.

- Hameed, S., Qureshi, M.A.;, Kaushik, A.M.;, Bias, A., Ashik, M., Qureshi, A.M., and Kaushik, A., 2024. Bias Mitigation via Synthetic Data Generation: A Review. Electronics 2024, Vol. 13, Page 3909, 13 (19), 3909.

- Hamghalam, M. and Simpson, A.L., 2024. Medical image synthesis via conditional GANs: Application to segmenting brain tumours. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 170, 107982. [CrossRef]

- Heenaye-Mamode Khan, M., Gooda Sahib-Kaudeer, N., Dayalen, M., Mahomedaly, F., Sinha, G.R., Nagwanshi, K.K., and Taylor, A., 2022. Multi-Class Skin Problem Classification Using Deep Generative Adversarial Network (DGAN). Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022 (1), 1797471. [CrossRef]

- Hradec, J.., Craglia, M.., Di Leo, M.., De Nigris, S.., Ostlaender, N.., and Nicholson, N.., 2022. Multipurpose synthetic population for policy applications.

- Huang, H., li, zhihang, He, R., Sun, Z., and Tan, T., 2018. IntroVAE: Introspective Variational Autoencoders for Photographic Image Synthesis. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 31.

- Kapania, S., Ballard, S., Kessler, A., and Vaughan, J.W., 2025. Examining the Expanding Role of Synthetic Data Throughout the AI Development Pipeline, 45–60.

- Karras, T., Laine, S., and Aila, T., 2019. A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks.

- Kumar, Y., Koul, A., Singla, R., and Ijaz, M.F., 2022. Artificial intelligence in disease diagnosis: a systematic literature review, synthesizing framework and future research agenda. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2021 14:7, 14 (7), 8459–8486. [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.H. and Ye, J.C., 2017. Geometric GAN.

- Makhlouf, A., Maayah, M., Abughanam, N., and Catal, C., 2023. The use of generative adversarial networks in medical image augmentation. Neural Computing and Applications, 35 (34), 24055–24068. [CrossRef]

- Mao, X., Li, Q., Xie, H., Lau, R.Y.K., Wang, Z., and Paul Smolley, S., 2017. Least Squares Generative Adversarial Networks.

- Mehmood Qureshi, A., Kaushik, A., Regan, G., Mcdaid, K., and Mccaffery, F., 2024. Handling Class Imbalance via Counterfactual Generation in Medical Datasets.

- Mehrabi, N., Morstatter, F., Saxena, N., Lerman, K., and Galstyan, A., 2021. A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 54 (6). [CrossRef]

- Mittermaier, M., Raza, M.M., and Kvedar, J.C., 2023. Bias in AI-based models for medical applications: challenges and mitigation strategies. npj Digital Medicine, 6 (1), 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Park, T., Liu, M.-Y., Wang, T.-C., and Zhu, J.-Y., 2019. Semantic Image Synthesis With Spatially-Adaptive Normalization.

- Pezoulas, V.C., Zaridis, D.I., Mylona, E., Androutsos, C., Apostolidis, K., Tachos, N.S., and Fotiadis, D.I., 2024. Synthetic data generation methods in healthcare: A review on open-source tools and methods. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 23, 2892–2910. [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, M., Noei, S., Robbi, E., Cima, L., Moroni, M., Munari, E., Torresani, E., and Jurman, G., 2024a. Generating and evaluating synthetic data in digital pathology through diffusion models. Scientific Reports 2024 14:1, 14 (1), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Price, W.N.I., 2019. Medical AI and Contextual Bias. Harvard Journal of Law & Technology (Harvard JOLT), 33.

- Qureshi, A.M., Kaushik, A., Loughran, R., and McCaffery, F., 2026. BCONDS: Borderline Counterfactual Oversampling with Noise Elimination and Density Scoring, 422–432.

- Rujas, M., Martín Gómez del Moral Herranz, R., Fico, G., and Merino-Barbancho, B., 2025. Synthetic data generation in healthcare: A scoping review of reviews on domains, motivations, and future applications. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 195, 105763. [CrossRef]

- Saba, T., 2020. Recent advancement in cancer detection using machine learning: Systematic survey of decades, comparisons and challenges. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 13 (9), 1274–1289. [CrossRef]

- Skandarani, Y., Jodoin, P.M., and Lalande, A., 2023. GANs for Medical Image Synthesis: An Empirical Study. Journal of Imaging, 9 (3), 69. [CrossRef]

- Sufi, F., 2024. Addressing Data Scarcity in the Medical Domain: A GPT-Based Approach for Synthetic Data Generation and Feature Extraction. Information 2024, Vol. 15, Page 264, 15 (5), 264. [CrossRef]

- Team, K., 2024. 5 Major Disadvantages of AI in Healthcare. Retrieved July 28, 2025, from https://www.keragon.com/blog/disadvantages-of-ai-in-healthcare.

- Thambawita, V., Salehi, P., Sheshkal, S.A., Hicks, S.A., Hammer, H.L., Parasa, S., de Lange, T., Halvorsen, P., and Riegler, M.A., 2022. SinGAN-Seg: Synthetic training data generation for medical image segmentation. PLOS ONE, 17 (5), e0267976. [CrossRef]

- Vadisetty, R., Polamarasetti, A., and Sufiyan, M., 2024. Generative AI: A Pix2pix-GAN-Based Machine Learning Approach for Robust and Efficient Lung Segmentation. 2024 Asian Conference on Intelligent Technologies, ACOIT 2024.

- Vipul Arya, K. and Sathya, D., 2025. Generation of Synthetic Dataset for Electronic Health Record (EHR) and Medical Images. Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems, ICICCS 2025, 749–756.

- Waisberg, E., Ong, J., Kamran, S.A., Masalkhi, M., Paladugu, P., Zaman, N., Lee, A.G., and Tavakkoli, A., 2025. Generative artificial intelligence in ophthalmology. Survey of Ophthalmology, 70 (1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., 2024. Variational Autoencoder. Medium. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from https://medium.com/@jimwang3589/variational-autoencoder-vae-7609893c80f4.

- Zulfiqar, A., Muhammad Daudpota, S., Shariq Imran, A., Kastrati, Z., Ullah, M., and Sadhwani, S., 2024. Synthetic Image Generation Using Deep Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Computational Intelligence, 40 (5), e70002. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).