Submitted:

17 December 2025

Posted:

18 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

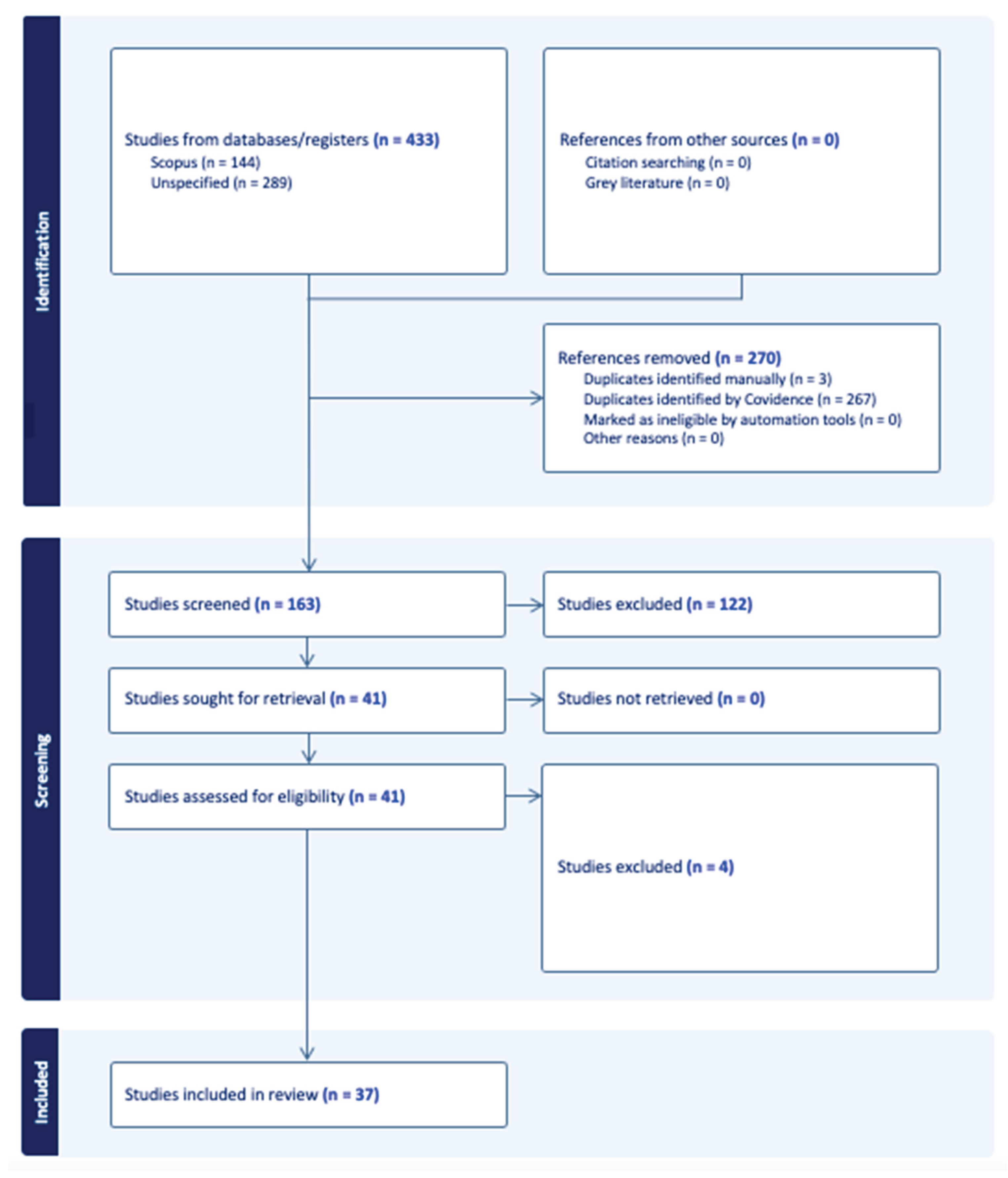

2. Materials and Methods

| Element | Description | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Adults who are mental health service users. | -Adults above 18 years of age who were mental health service users. -Community dwelling populations. |

-Adolescents under 18 years of age. -Populations not in community settings (eg. Prisons). |

| Concept | Perspectives of mental health service users. | -Studies reporting mental health data separately. -Studies reporting service user perspectives and/or lived experiences of cancer screening. |

-Studies not reporting mental health data separately. -Studies not reporting service user perspectives and/or lived experiences of cancer screening. |

| Context | Health system and community settings. | -Community based settings with primary/secondary/ tertiary health system contact points. | -Non-community settings/institutions. |

| Type of Evidence Source | Publication type | -Peer-reviewed journal articles. | -Editorials. -Conference papers. -Unpublished theses. -Reports. -Study protocol papers. -Epidemiological studies. |

| Time Frame | Publication period. | -Inception to February 18, 2024. | -Publications outside this time frame. |

| Language | Language of the publication. | -English. | -Non-English. |

3. Results

3.1. Social Determinants of Health as a Barrier

3.1.1. Education

3.1.2. Age

3.1.3. Low Income and Finances

3.1.4. Distance

3.1.5. Reduced Access

3.1.6. Gender and Socio-Economic Status

3.1.7. Culture

3.1.8. Never Married

3.1.9. Reproductive History

3.2. Mental Health or Medical Comorbidities as a Barrier

3.2.1. Mental Health Condition and Severity

3.2.2. Medical (Non-Psychiatric) Comorbidities

3.2.3. Cognitive Difficulties/Impairment and Motivation

3.2.4. Embarrassment/Stigma/Shame

3.2.5. Patient Concerns About Screening (eg. Trauma, Procedures, Fear)

3.2.6. Smoking

3.3. The Health System as a Barrier

3.3.1. Delaying Care/Prioritization

3.3.2. No Primary Care Provider

3.3.3. Siloed Health Systems

3.3.4. Physician Knowledge/Identification of Screening Candidates

3.3.5. Negative Attitudes and Diagnostic Overshadowing

3.4. Social Determinants of Health as a Facilitator

3.5. Increasing Uptake in the Health System as a Facilitator

3.5.1. Knowledge

3.5.2. Professional Role and Identity

3.5.3. Participation, Targeted Invitations, Phone Counselling

3.5.4. Test Convenience

3.5.5. Community-Based Cancer Navigators

3.5.6. Service Integration

3.6. Trust in the Service and Health Professionals as a Facilitator

3.6.1. Trust and Positive Experience

3.6.2. Healthcare Provider Gender

3.7. Presence and Nature of Support as a Facilitator

3.7.1. Support

3.7.2. Presence of a Primary Care Provider and Continuity of Care

3.8. Positive Approach to Self-Care as a Facilitator

3.8.1. Self-Care

3.8.2. Awareness of Physical Symptoms

3.8.3. Diagnosis and Mental Health

4. Discussion

4.1. Alignment with Broader Public Health Frameworks

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| v.18 | Version 2018 |

| CASP | Critical Appraisal Skills Programme |

| NSW | New South Wales |

| NHO | Non-Hispanic other |

| NHW | Non-Hispanic White |

| NHB | Non-Hispanic Black |

| FIT | Faecal Immunochemical Test |

| gFOBT | Guaiac Faecal Occult Blood Test |

| USA | United States of America |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| CMHC | Community Mental Health Clinic |

| PCP | Primary care providers |

| RACGP | Royal Australian College of General Practitioners |

| GP | General Practitioner |

| HPV | Human papilloma virus |

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer. Fact Sheet, World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- World Health Organizatio. Mental Disorders. Fact Sheet, World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Kaine, C.; Lawn, S.; Roberts, R.; Cobb, L.; Erskine, V. Review of Physical and Mental Health Care in Australia. Lived Experience Australia Ltd., Marden, South Australia, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://www.livedexperienceaustralia.com.au/_files/ugd/07109d_c21aa5b21f1d45c687b453f0adbb725f.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Equally Well Australia. Factsheer #8: Breast Cancer and Mental Health. Equally Well. 2025. Available online: https://equallywell.org.au/equally-well-factsheets/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Colton, C.W.; Manderscheid, R.W. Congruencies in Increased Mortality Rates, Years of Potential Life Lost, and Causes of Death Among Public Mental Health Clients in Eight States. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2006, 3(2), A42. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, R.; Johnson, C. The Potential Impact of a Public Health Approach to Improving the Physical Health of People Living with Mental Illness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19(18), 11746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R. The Physical Health of People Living With a Mental Illness: A Narrative Literature Review. Equally Well Publications and Reports. September 2019. Available online: https://www.equallywell.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Literature-review-EquallyWell-2a.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Kisely, S.; Siskind, D. Excess Mortality From Cancer in People With Mental Illness- Out of Sight and Out of Mind. Acta. Psychiatr. Scand. 2021, 144(4), 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Criteria and User Manual (Version 2018). 1 August 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_crtieria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2014).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2008, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Heealth. WHO Fact Sheets. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/social-determinants-of-health (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Aggarwal, A.; Pandurangi, A. Disparities in Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening in Women with Mental Illness: A Systematic Literature Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44(4), 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, E.; Juul, K.E. Factors Associated with Non-participation in Cervical Cancer Screening – A Nationwide Study of Nearly Half a Milion Women in Denmark. Prev. Med. 2018, 111, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, K.E.; Steffens, E.B. Lung Cancer Screening Eligiblity, Risk Perceptions, and Clinician Delivery of Tobacco Cessation Among Patients with Schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70(10), 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siantz, E.; Wu, B. Mental Illness Is Not Associated with Adherence to Colorectal Cancer Screening: Results from the California Health Interview Survey. Dig. Dis. Sci. Serv. 2017, 62, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Mkuu, R. Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms and Missing Breast Cancer and Cervical Screening: Results from Brazos Valley Community Health Survey. Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 25(4), 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, E.M.; Lau, M. Participation in a Swedish Cervical Cancer Screening Program Among Women with Psychiatric Diagnoses: A Population-based Cohort Study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cespedes, P.; Sanchez-Martinez, V. Delay in the Diagnosis of Breast and Colorectal Cancer in People with Severe Mental Disorders. Cancer Nurs. 2020, 43(6), E356–E362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, E.A.; Borschmann, R.D. Interventions to Encourage Uptake of Cancer Screening for People with Severe Mental Illness (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2013, Issue 7. Art. No., CD009641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley, E.A.; Borschmann, R.D. Interventions to Encourage Uptake of Cancer Screening for People with Severe Mental Illness (Review). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. 2016, Issue 9. Art. No., CD009641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrull-Guardeno, J.; Dominguez, A. Cervical Cancer Screening in Women with Severe Mental Disorders: An Approach to the Spanish Context. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 42(4), E31–E35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werneke, U.; Horn, O. Uptake of Screening for Breast Cancer in Patients with Mental Health Problems. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60(7), 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impelido, M.L.; Brewer, K. Age-specific Differences in Cervical Cancer Screening Rates in Women Using Mental Health Services in New South Wales, Australia. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2023, 58(10), 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeth, C.; Burgess, P. Breast Cancer Screening Participation in Women Using Mental Health Services in NSW, Australia: A Population Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2023, 59, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillargeon, J.; Kuo, Y. Effect of Mental Disorders on Diagnosis, Treatment, and Survival of Older Adults with Colon Cancer. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011, 59(7), 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, A.M.; Pirraglia, P.A. Quality of General Medical Care Among Patients with Serious Mental Illness: Does Colocation of Services Matter? Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62(8), 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.; Hancock, K.J. Cancer and Mental Illness. In Comorbidity of Mental and Physical Disorders, 1st ed.; Sartorius, N., Holt, R.I.G., Eds.; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 179, pp. 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkuu, R.S.; Staras, S.A. Clinicians’ Perceptions of Barriesr to Cervical Cancer Screening for Women Living With Behavioural Health Conditions: A Focus Group Study. BMC Cancer. 2022, 22(1), 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.A.; Stone, E.M. Cancer Screening Among Adults With and Without Serious Mental Illness: A Mixed Methods Study. Med. Care. 2021, 59(4), 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.; Bevel, M.S. Racial/Ethnic Disparity in the Relationship of Mental and Physical Health With colorectal Cancer Screening Utilization Among Breast and Prostate Cancer Survivors. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19(5), E714–E724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, A.; Burgess, C. Influences on Uptake of Cancer Screening in Mental Health Service Users: A Qualitative Study. JCO BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16(1), 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, C.; Cunningham, R. Cervical and Breast Cancer Screening Uptake Among Women with Serious Mental Illness: A Data Linkage Study. BMC Cancer. 2016, 16(1), 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Scott, D. Provision of Preventive Services for Cancer and Infectious Diseases Among Individuals With Serious Mental Illness. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2012, 26(3), 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linz, S.; Jerome-D’Emilia, B. Barriers and Facilitators to Breast Cancer Screening for Women With Severe Mental Illness. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2022, 30(3), 576–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouk, M.; Edwards, J.D. Psychiatric Morbidity and Cervical Cancer Screening: A Retrospective Population-Based Case-Cohort Study. CMAJ Open. 2020, 8(1), E134–E141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigod, S.N.; Kurdyak, P.A. Depressive Symptoms As A Determinant of Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening in Women: A Populaiton-based Study in Ontario, Canada. Arch. Women’s Ment. H/ealth. 2011, 14(2), 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koroukian, S.M.; Bakaki, P.M. Mental Illness and Use of Screening Mammography Among Medicaid Beneficiaries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42(6), 606–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Perelra, I.E.S. Breast Cancer Screning in Women with Mental Illness: Comparative Meta-Analysis of Mammography Uptake. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2014, 205(6), 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domino, M.E.; Wells, R. Serving Persons with Severe Mental Illness in Primary Care-based Medical Homes. Psychiatr. Serv. 2015, 66(5), 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, G.; Lambeth, C. Breast Screening Participation and Degree of Spread of Invasive Breast Cancer at Diagnosis in Mental Health Service Users, a Population Linkage Study. Cancer. 2023, 130(1), 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukhnaova, M.A.; Tillotson, C.J. Uptake of Preventive Services Among Patients With and Without Multimorbidity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59(5), 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, K.E.; Henderson, D.C. Cancer Care for Individuals With Schizophrenia. Cancer. 2014, 120(3), 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L.; McFarland, D. The Risk and the Course of Cancer Among People With Severe Mental Illness. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2023, 19, e174501792301032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarborough, B.J.H.; Hanson, G.C. Colorectal Cancer Screening Completion Among Individuals With and Without Mental Illnesses: A Comparison of 2 Screening Methods. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32(4), 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; James, M. Mammography Among Women With Severe Mental Illness: Exploring Disparities Through A Large Retrospective Cohort Study. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69(1), 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.K.; Jorgensen, M.D. Mental Disordres, Participation, and Tajectories in the Danish Colorectal Cancer Programme: A Population-based Cohort Study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023, 10(7), 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuelo, C.; Ashburner, J.M. Colorectal Cancer Screening Patient Navigation for Patients with Mental Illness and/or Substance Use Disorder: Pilot Randomized Control Trial. J. Dual Diagn. 2020, 16(4), 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodl, M.M.; Powell, A.A. Mental Health, Frequency of Healthcare Visits, and Colorectal Cancer Screening. Med. Care 2010, 48(10), 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Australia. Welcome- Australian Cancer Plan. Australian Cancer Plan. Available online: https://www.australiancancerplan.gov.au/welcome (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Tran, M.; Ee, C.; Rhee, J.; Bareham, M. General Practice, Mental Health and the Care of People with Cancer. Australian Journal of General Practice 2025, 54(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS England. NHS Long Term Plan Ambitions for Cancer. NHS England. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/strategy/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Public Health England. Severe Mental Illness (SMI): Inequalities in Cancer Screening Uptake Report. GOV.UK. Pubished 21 September 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk.government/publications/severe-mental-illness-inequalities-in-cancer-screening-uptake/severe-mental-illness-smi-inequalities-in-cancer-screening-uptake-report (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- National Cancer Plan. About the National Cancer Plan. NationalCancerPlan.cancer.gov. Available online: https://nationalcancerplan.cancer.gov/about (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Cancer Strategy for Cancer Control. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Available online: https://www.partnershipagainstcancer.ca/cancer-strategy/ (accessed on 9 December 2025).

| Type of Cancer Screening Focused on | Number of studies/ articles | Cited Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | 8 | [22,24,34,37,38,40,45]. |

| Cervical | 6 | [13,17,21,23,28,35]. |

| Breast and cervical | 4 | [12,16,32,36]. |

| Colon | 3 | [15,25,46]. |

| Lung | 1 | [14]. |

| Breast and colon | 1 | [18]. |

| Breast and bowel | 1 | [31]. |

| Breast and prostate | 1 | [30]. |

| Recommendation | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Improve health system | -Tailored interventions. -Target groups, risk factors, areas of concern. -Physical and mental health system integration. -Address barriers at service user and physician levels. -Revise current care models. Consider implementing co-location of services. |

| Social determinants of health | -Increase funding. -Understand insurance schemes. -Cultural safety. Address racial/ethnic disparities. Various languages. -Patient navigation programs. -Educate providers and patients. |

| Improve participation | -Directly ask about screening. -Prompt patients. -Address issues at screening invitation process. -Reduce stigma around mental illness. -Improve communication. -Support systems. |

| Research | -Barriers and facilitators of cancer screening. -Interventions and care settings. |

| Other / miscellaneous |

-Individual, policy, and system level strategies. -Guidelines and policies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).