Submitted:

16 December 2025

Posted:

17 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

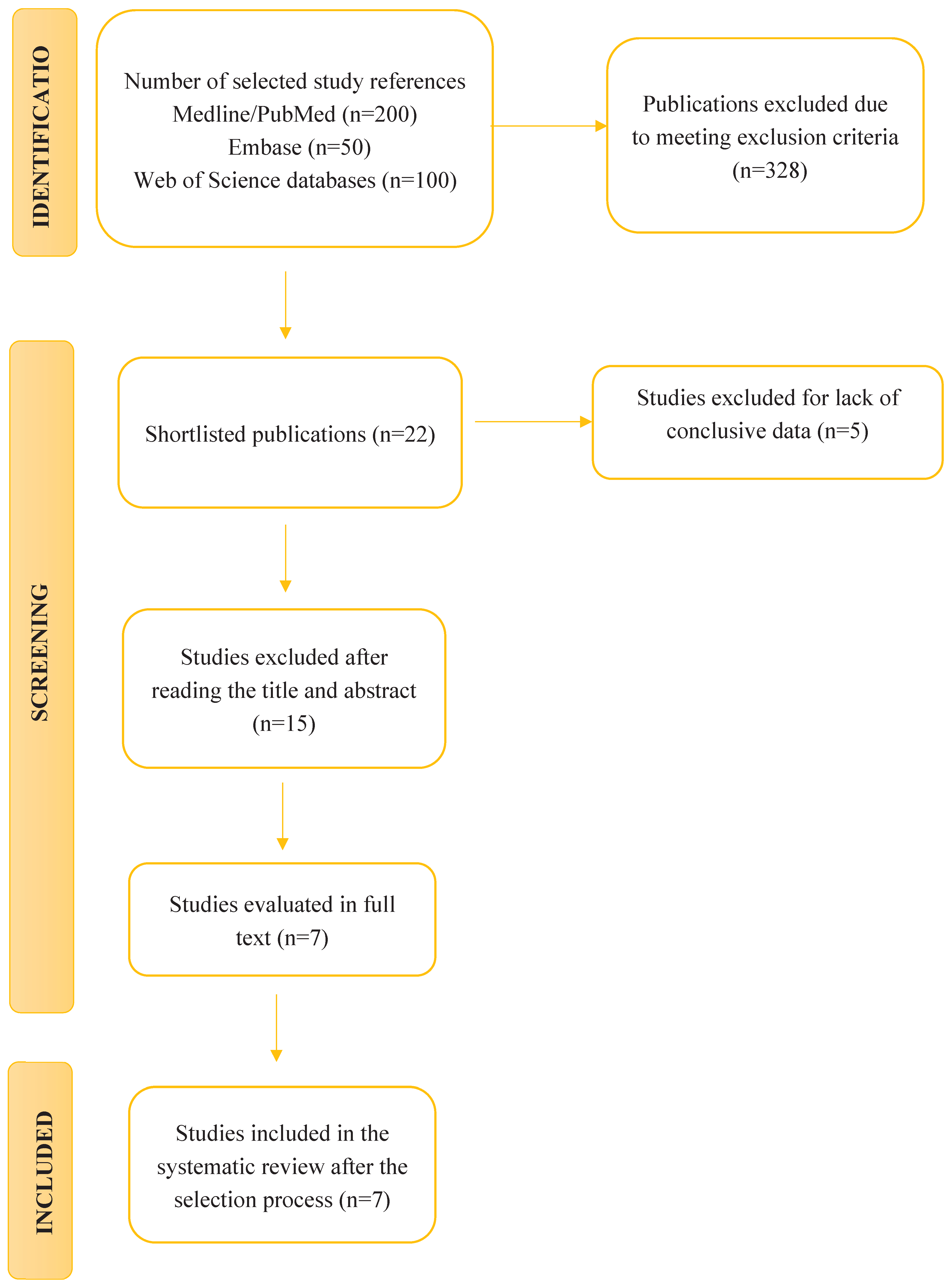

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Article Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Study Selection

3.2. Results of the Effects of Pesticides Exposure on Humans

| AUTHOR YEAR |

PESTICIDE | SAMPLE AND/OR TYPE OF STUDY | CHANGES IN THE INTESTINAL MICROBIOME/BRAIN DISORDERS | RESULTS | CONCLUSIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Yue, Y. et al. 2024 |

Insecticide (β-HCH) | Human mothers | Weight loss in offspring. | This study concludes that prenatal exposure to pesticides induces changes in the gut microbiome that lead to intestinal dysbiosis, impacting health and behavior, affecting key bacterial strains and contributing to conditions such as weight fluctuations, energy homeostasis and neurobehavioral symptoms like autism. Low body weight and modifications in bacterial genes associated with carbohydrate and lipid metabolism have been identified, as well as behavioral abnormalities in offspring. Obesity, metabolic disorders, alterations in immunity and inflammation have also been observed. These findings underscore the importance of investigating the effects of pesticides on the microbiome and their role in the development of metabolic and neurological diseases. | |

| Insecticide (Mecarbam) | Human mothers | Weight loss in offspring. | |||

| Herbicide (Ammonium glufosinate) | Father mice | Behavioral abnormalities. | |||

| Insecticide (Combination of boscalid, captan, chlorpyrifos, thiacloprid, thiophanate, and ziram) |

Father mice | Obesity and metabolic disorders. | |||

| Insecticide (Chlorpyrifos) | Rat offspring | Hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia in female offspring. Changes in rat behavior when faced with new situations. Changes in glutamine function and GABA signaling in the amygdala. |

|||

| Mouse offspring | Interference with developing neurones. | ||||

| Insecticide (Nitenpyram | Parent mice | Decrease in serum glucose in female offspring. | |||

| Fungicide (Procymidone) | Progenitor rats | Metabolic disorders. Neurological impairments throughout life. | |||

| Parent mice | Metabolic disorders. Neurodevelopmental disorders in sex-dependent offspring. | ||||

| Insecticide (Fenvalerate) | Parent mice | Increased intrauterine wet weight. Increased height of luminal epithelial cells. Increased LH. | |||

| Insecticide (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) | Parent mice | Neurodevelopmental defects in male mice. | |||

| Insecticide (Cypermethrin) | Parent mice | Hearing impairments that develop slowly over time. | |||

| Fungicide (Triticonazole) | Progenitor rats | Alteration of endocrine effects. Changes in the genome transcription of the external genitalia of the male fetus. |

|||

| Fungicide (Flusilazole) | Progenitor rats | Alteration of endocrine effects. | |||

| Insecticide (Chlordecone) | Parent mice | Defects and reduction in sperm count. | |||

| Herbicide (Glyphosate) | Progenitor rats | Prostate disease, obesity, kidney disease, ovarian disease, and birth abnormalities. Changes related to inflammation and oxidative stress genes in the cortex and cerebellum of offspring. |

|||

| Herbicide (paraquat) | Baby mice | Increased weight in adults among descendants. | |||

| Herbicide (ammonium glufosinate) | Parent mice | Abnormal behaviour. | |||

| Insecticide (permethrin) | Baby mouse | Negative impact on gut microbiota | |||

| Insecticide (endosulfan) | Parent mice | Metabolic disorders. Obesity. | |||

| Insecticide (chlorpyrifos) | Parent rats | Negative impact on gut microbiota Profound changes in the microbiome of the caecum |

Bacterial translocation in the liver and spleen. Lower birth rate. | ||

| Mouse offspring | egative impact on gut microbiota | Dysbiosis at an early age in the intestinal membrane. | |||

| Rat offspring | Microbiome modifications | Hyperlipidemia in female offspring. Hypoglycemic alterations in female offspring. Alterations in rat behavior in new situations. Reduced immune response in females. Asthma. | |||

| Insecticide (Nitenpyram) | Parent mice | Decrease in blood glucose in female offspring. | |||

|

Yang, Y. et al. 2023 |

Glyphosate | Case-control study of pregnant women | Increased risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring of pregnant women living less than 2000 meters from places where herbicides are used. | This study establishes a link between alterations in the gut microbiome and autism spectrum disorder. Exposure to pesticides causes dysbiosis in gut microbiota and neurodevelopment, contributing to neurological defects and behavioral alterations. In summary, dysbiosis of the gut microbiome is a crucial factor in the symptoms of autism spectrum disorder related to pesticides exposure. |

|

| Sprague-Dawley rats | Changes in maternal behavior. Changes in neural plasticity. | Perinatal exposure leads to changes in the behavior of rat offspring. | |||

| ddY mice | Cognitive impairment. Social interaction impairment | Behavioral abnormalities like autism spectrum disorder in the offspring of male mice. | |||

| Swiss mice | Deficit in social interaction. Repetitive stereotypical behavior. Morphological changes in glial cells residing in the brain. Reduction in blood-brain barrier permeability. Alteration in acetylcholinesterase activity. | ||||

| Chlorpyrifos | Case-control study of pregnant women | Exposure in mothers positively correlates with autism spectrum disorder in offspring. | |||

| Cohort study pregnant women |

Inverse association between prenatal exposure and domain-specific neuropsychological development in children at 12 months. | ||||

| Cohort study pregnant women |

Increased autistic traits in 11-year-old children with prenatal exposure. | ||||

| Case-control study of pregnant women | Increased risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring of mothers exposed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy. | ||||

| Case-control study of pregnant women | Higher risk of autism spectrum disorder with greater exposure during pregnancy. | ||||

| Sprague-Dawley rats | Existence of behaviors typical of autism spectrum disorder phenotypes (impaired social communication and confined and repetitive behavior). | ||||

| BTBR mice | Exposure during prenatal development promotes the existence of behavioral traits typical of autism spectrum disorder, including impairments in social and communication domains (alterations in ultrasonic vocalization and high levels of repetitive behaviors). | ||||

| Wistar rats | Hypermobility and stress-related hypermobility. Hypo- or hypersensitisation of the cholinergic and GABAergic systems. Increased transcription of the GABA-A-A2 subunit and M2 receptor genes. Inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity. Stimulation of pituitary hormone release. Systemic inflammation (TNFR). Decreased responsiveness to social novelty in adulthood. | Communication deficits similar to those seen in autism spectrum disorder. | |||

| C57BL/6 mice | Exposure during prenatal development is associated with long-term negative effects on social behavior and decreased exploration of unfamiliar items. | ||||

| C57BL/6 mice | Exposure during prenatal development caused impairments in social behavior and excitatory-inhibitory balance. | ||||

| Fmr1-KO rats | Exposure during development led to exacerbation of a phenotype like autism spectrum disorder. | ||||

| Pyrethroids | Case-control study of pregnant women | Exposure during the third trimester was associated with an increased likelihood of presenting symptoms of autism spectrum disorder. | |||

| Cross-sectional study of pregnant women | Higher levels of pyrethroids in urine were associated with an increased risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring. | ||||

| Case-control study pregnant women |

Prenatal exposure was associated with an increased risk of autism spectrum disorder. | ||||

| Wistar rats | Loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. | ||||

| C57BL/6 mice | Neuronal inflammation. | ||||

| Imidacloprid |

Case-control study pregnant women |

Increased risk of autism spectrum disorder in offspring in 30% of cases. | |||

| Diazinon | C57BL/6 mice | Decreased regulation of neurotransmitters. | |||

| Glufosinate ammonium |

ICR mice | Impaired motor activity. Behaviors similar to autism spectrum disorder. Impaired short-term memory formation. | |||

|

Gambarte, P. C. K. & Wolansky, M. J. 2022 |

Organophosphate insecticides (Chlorpyrifos) |

Kunming male mice | Alteration of the composition of the microbiota and metabolic pathways | This study has confirmed the existence of alterations in the gut microbiome that lead to a reduction in beneficial bacteria and an increase in harmful bacteria, causing intestinal dysbiosis. Obesity, diabetes, alterations in the inflammatory response, changes in the genome, and morphological and functional changes in the intestine have been identified as a consequence of pesticides use. Alterations in gene expression related to metabolic pathways, glucose intolerance, and pesticide biotransformation have also been demonstrated. | |

| Male Wistar rats | Alteration of the composition of the microbiota. Increase in the abundance of opportunistic pathogens. |

Microbiota alterations are associated with obesity, diabetes phenotypes, and alterations in pancreatic islet cells. Alteration of the mechanism responsible for controlling the inflammatory response. Micro- and macrostructural alterations in the right intestine. | |||

| Organophosphate insecticides (Diazinon) | C57BL/6 mice | Changes in the composition of the gut microbiome. | Changes in the functional metagenome and metabolic pathways. Differences are observed depending on the sex of the mouse. | ||

| Organophosphate insecticides (Monochrotophos) | Rats, CFT-Wistar | Changes in the composition of the gut microbiome. | Functional and morphological changes in the intestine. | ||

| Mice, BALB/c | Changes in the composition of the gut microbiome. | Changes in the expression of genes related to metabolic pathways, glucose intolerance and pesticide biotransformation. | |||

| Carbamate insecticide (Aldicarb) | C57BL/6 mice | Alteration of the composition of the microbiota. | Specific changes throughout exposure in the microbiome for each genus of bacteria. | ||

| Pyrethroid insecticide (Permethrin) | Male Wistar rats and lactating offspring | Alteration of the composition of the microbiota. | Reduction in beneficial bacterial genera and increase in non-beneficial bacterial genera compared to the control. | ||

| Systemic fungicide (Propamocarb) |

ICR male mice | Changes in the composition of the gut microbiome 7 days after the start of oral exposure. | |||

| Fungicide carbamate benzimidazole (Carbendazim) |

ICR male mice | Alteration of the microbiome composition after 7 days. | Increase in harmful bacteria and decrease in beneficial bacteria. | ||

| Male C57BL/6 mice | Alteration of the microbiome composition after 7 days. | Increases and decreases in relative abundance depending on bacterial gender (beneficial and harmful). | |||

| Fungicide triazole compounds (Epoxiconazole) |

Female Sprague-Dawley rats | Alteration of the microbiome composition. | Increases and decreases in relative abundance depending on bacterial genus. | ||

| Herbicide Organophosphate (Glyphosate) |

Sprague-Dawley rats | Gut microbiota dysbiosis and sex-dependent effects at all doses examined. | |||

| Herbicide phenoxyacetic acid (2,4 D) | Male C57BL/6 mice | Increase and decrease in relative microbial abundance based on bacterial genus. | |||

|

Djekkoun, N. et al. 2021. |

Organophosphates (Chlorpyrifos) | Rats | Higher number of harmful bacteria. Lower number of beneficial bacteria. Increase in potentially pathogenic flora. Decrease in beneficial flora | No impact or increase in body weight in adults. Low body mass and short body length at birth. Changes in plasma glucose levels and lipid profile. Significant difference in body weight. | This study has shown that exposure to pesticides modulates bacterial populations, impacting the health of the host. Intestinal dysbiosis induced by these compounds is associated with alterations similar to those observed in metabolic syndrome, where bacterial translocation, increased intestinal permeability and microbial dysmetabolism generate low-grade inflammation. These mechanisms contribute to imbalances in energy homeostasis and increase the risk of developing chronic inflammatory diseases. It has been demonstrated that various pesticides can induce endotoxemia, mucosal permeability, and proinflammatory activation, leading to systemic inflammatory responses. Alterations in microbial substrates in the intestine have also been observed, leading to changes in short-chain fatty acid profiles and altering energy collection through targeted dysbiosis, reinforcing their role in metabolic disruption and the development of chronic inflammatory pathologies. Pesticides alter the gut microbiome, influence energy metabolism and promote low-grade inflammation. They also impact on metabolic health and the development of chronic diseases. |

| Mice | Increase in potentially pathogenic flora. Decrease in beneficial flora. | Abnormal permeability. | |||

| Organophosphates (Diazinon) | Mice | Altered microbiome composition. |

Impaired energy metabolism. Male animals are more susceptible to abnormal translocation. Reduced body weight gain. |

||

| C57BL/6 mice | Increase in potentially pathogenic flora. Decrease in beneficial flora. | Significant increase in body, liver and epididymal fat. Increase in serum TG and glucose levels. | |||

| Organophosphates (MCP) | Mice | Increase in potentially pathogenic flora. |

Increased blood sugar levels. Glucose intolerance. | ||

| Organochlorines (TCDF) | Rats | Decrease in beneficial flora. | It causes inflammation and alters hepatic lipogenesis, gluconeogenesis, and glycogenolysis. | ||

| Organochlorines (DDT) | Rats | Increase in potentially pathogenic flora. Decrease in beneficial flora | Increased weight gain. Increased fasting glucose and insulin. Disturbed lipid metabolism. | ||

| Organochlorines (PCP) | Female mice | Increase in potentially pathogenic flora. Decrease in beneficial flora. | Reduction in body weight. | ||

| Benzimidazoles (CBZ) | Mice | Increase in potentially pathogenic flora. Decrease in beneficial flora. | Accumulation of liver lipids. Increase in TG, cholesterol, HDL, and LDL. |

||

|

Utembe, W. & Kamng’ona, A. W. 2021 |

Data collected in other reviews. | Case-control studies in humans. Cohort studies in humans. Rats. Mice. |

Glyphosate. Chlorpyrifos. Pyrethroids. Imidacloprid. Diazinon. Ammonium glufosinate. |

This study confirms the existence of cognitive deficits, motor dysfunction, stress-related hypermobility, social interaction dysfunction, reduced responsiveness to social novelty in adults, short-term memory impairment, changes in maternal behavior, and neural plasticity along with repetitive stereotypical behavior. Behaviors similar to those of autism spectrum disorder are observed. In addition, morphological changes in glial cells residing in the brain and reduced blood-brain barrier permeability are confirmed. There are also changes in the levels of short-chain fatty acids in the brain, along with negative regulation of neurotransmitters. Alteration of acetylcholinesterase activity, implying its inhibition. Hypo- or hypersensitization of cholinergic and GABAergic systems. Loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and neuronal inflammation. There is also evidence of increased transcription of the GABA-A-A2 subunit and M2 receptor genes, along with stimulation of pituitary hormone release (TNF-α, etc.). There is also increased oxidative stress, which promotes ageing and chronic diseases. | |

|

Meng, Z. et al. 2020 |

Organophosphate insecticide (Malathion) | Mice | Disorders of the composition of the gut microbiota. | Altered genes involved in quorum sensing, increased motility, pathogenicity, and genes related to cell wall components. | This work leads us to understand that exposure to pesticides can modify the composition of the gut microbiome, which, in turn, alters the production and function of its key metabolites. Metabolic profile disorders, insulin resistance, and obesity have been identified. Exposure to these substances can negatively affect health, especially the digestive system and metabolism. It has been proven that an initial impact on the delayed maturation of the digestive tract influences nutrient absorption and promotes weight gain and lipid accumulation. This imbalance in lipid metabolism generates inflammation, which interferes with bile acid metabolism and can cause enterohepatic disorders, increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition, chronic colon inflammation and liver toxicity aggravate overall health, reflecting metabolic disorders and alterations in digestive function. These effects underscore the importance of understanding the interactions between the gut microbiome and metabolism and environmental factors in the development of chronic diseases. |

| Organophosphate insecticide (Diazinon) | Mice | Alterations in the gut microbiota. | Metabolic profile disorders. | ||

| Organophosphate insecticide (Chlorpyrifos) | Mice | Intestinal inflammation and abnormal permeability. | Insulin resistance and obesity. | ||

| Rats |

Delayed maturation of the digestive tract. | ||||

| Organophosphate insecticide (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) | Rats |

Weight gain and lipid accumulation. | |||

| Pyrethroid insecticide (Permethrin) | Baby rats | Dyskinesia and intestinal disease. | |||

| Benzimidazole fungicide (Carbendazim) | Mice | Lipid metabolism disorder and inflammation. | |||

| Lipid metabolism disorder and inflammation. | |||||

| Systemic fungicide (Propamocarb) |

Mice | Disorders of lipid and bile acid metabolism. | |||

| Disorders of enterohepatic metabolism and possible cardiovascular disease. | |||||

| Systemic fungicide that inhibits ergosterol (Imazalil) |

Mice | Colon inflammation. | |||

| Systemic fungicide containing triazole compounds (Epoxiconazole) |

Rats | Hepatic toxicity. | |||

| Systemic fungicide composed of Triazole (Penconazole and its enantiomers) | Mice | Intestinal microbiota disorders. | Metabolic profile disorders. | ||

|

Yuan, X. et al. 2019 |

Data collected in other reviews. | Human body fluids. Mice. NOD mice. Adult male C57BL/6 mice. Sprague-Dawley rats. Randomized study. Pregnant women. Prospective randomized study, mother-baby pairs. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study in patients with type 2 diabetes. Case-control study in humans. |

. | This work leads us to conclude that pesticides can alter the composition of the gut microbiome and its metabolites. It also suggests that changes in the gut microbiome and metabolites can cause adverse effects in the host, in the transduction of extracellular signals from the plasma membrane to the cell and along the intracellular chain to stimulate the cellular response. Different bile acids can bind to different receptors, which can lead to atherosclerosis, hepatic lipid metabolism disorders, and dysbiosis due to fat accumulation. Short-chain fatty acids derived from microbial fermentation of fibre can inhibit histone deacetylases and serve as energy substrates by directly activating G protein-coupled receptors. The action of short-chain fatty acids on the GPR receptor in fat cells can cause dysbiosis due to fat accumulation. In addition, innate immune cells activated by endotoxic bacteria can release various pro-inflammatory cytokines, inducing low-grade inflammation and even neuronal inflammation. The alteration of the intestinal microbiome balance and increased intestinal permeability due to pesticide absorption are potential risk factors for increasing the entry of molecules with higher molecular weight, leading to an inflammatory response and, ultimately, low-grade inflammation. Furthermore, the action of short-chain fatty acids in the brain can affect appetite and is therefore associated with obesity and diabetes. In short, pesticides can act on intestinal microbes, affect their metabolites, and destroy the mucosa and intestinal cells. These changes cause pathological changes by acting on receptor sites in different tissues and organs. |

3.3. Results of the Effects of Pesticides Exposure in Animal Models

3.3.1. Effects of Exposure in Rats

3.3.2. Effects of Gestational Exposure to Pesticides on Rat Offspring

3.3.3. Effects of Exposure on Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaur, R.; Choudhary, D.; Bali, S.; Singh Bandral, S.; Singh, V.; Ahmad, Md. A.; Rani, N.; Gurjeet Singh, T.; Chandrasekaran, B. Pesticides: An alarming detrimental to health and environment. Sci Total Environ 2024, 915:170113. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Kabir, E.; Jahan, S.A. Exposure to pesticides and the associated human health effects. Sci Total Environ 2017, 575:525-535. [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.A.; Eleftherohorinos, I.G. Pesticide exposure, safety issues, and risk assessment indicators. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011, 8(5):1402-1419. [CrossRef]

- Mostafalou, S.; Abdollahi, M. Pesticides: an update of human exposure and toxicity. Arch Toxicol 2017, 91(2):549-599. [CrossRef]

- Vehovszky, Á; Farkas, A.; Ács, A.; Stoliar, O.; Székács, U.; Mörtl, M.; Gyóri, J. Neonicotinoid insecticides inhibit cholinergic neurotransmission in a molluscan (Lymnaea stagnalis) nervous system. Aquat Toxico 2015, 167:172-179. [CrossRef]

- Czarnywojtek, A.; Jaz, K.; Ochmańska, A.; Zgorzalewicz-Stachowiak, M.; Czarnocka, B.; Sawicka-Gutaj, N.; Ziółkowska, P.; Krela-Kaźmierczak, Y.; Intestino, P.; Florek, E.; Ruchala, F. The effect of endocrine disruptors on the reproductive system - current knowledge. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021, 25(15):4930-4940. [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.L.Y.; Co, V.A.; El-Nezami, H. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and breast cancer: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62(24):6549-6576. [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.A.; Koutroubas, S.D. Farmers' Exposure to Pesticides: Toxicity Types and Ways of Prevention. Toxics 2016, 4(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.; Landrigan, P.J.; Balakrishnan, K.; Bathan, G.; Bose-O'Reilly, S.; Brauer, S.; Caravanos, J.; Chiles, T.; Cohen, A.; Corra, L.; et al. Pollution and health: a progress update. Lancet Planet Health 2022, 6(6):e535-e547. [CrossRef]

- Rajilić-Stojanović, M.; de Vos, W.M. The first 1000 cultured species of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2014, 38(5):996-1047. [CrossRef]

- Sommer F.; Bäckhed, F. The gut microbiota--masters of host development and physiology. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013, 11(4):227-238. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez,J.; Fernández Real, J.M.; Guarner, F.; Gueimonde, M.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Saenz de Pipaon, M.; Sanz, Y. Gut microbes and health. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 44, 7, 519-535. doi.org/10.1016/j.gastrohep.2021.01.009.

- Wang, J.; Hou, Y.; Mu, L.; Yang, M.; Ai, X. Gut microbiota contributes to the intestinal and extraintestinal immune homeostasis by balancing Th17/Treg cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 143(Pt 3):113570. [CrossRef]

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J 2017, 474(11):1823-1836. [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, J.R.; Adams, D.H.; Fava, F.; Hermes, G.D.A.; Hirschfield, G.M.; Hold, G.; Quraishi, M.N.; Kinross, J.; Smidt, H.; Tuohy, K.M.; Thomas, L.V.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Hart, H. The gut microbiota and host health: a new clinical frontier. Gut 2016, 65(2):330-339. [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Jordan, B.F. Gut microbiota-mediated inflammation in obesity: a link with gastrointestinal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 15(11):671-682. [CrossRef]

- Quigley, E.M.M. Microbiota-Brain-Gut Axis and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2017, 17(12):94. [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: a review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113(12):2019-2040. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19(1):55-71. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Gut microbiota derived metabolites in cardiovascular health and disease. Protein Cell 2018, 9(5):416-431. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Ishimoto, T.; Fu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. The Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12:733992. [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A.; Inoue, R.; Inatomi, O.; Bamba, S.; Naito, Y.; Andoh, A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin J Gastroenterol 2018, 11(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Goldbaum, A.A.; Bowers, L.W.; Cox, A.D.; Gillig, M.; Clapp Organski, A.; Cross, T.L. The Role of Diet and the Gut Microbiota in the Obesity-Colorectal Cancer Link. Nutr Cancer 2025, 77(6):626-639. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2023, 20(7):429-452. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N; Bilal, H.; Khan, S.; Shafiq, M.; Xiaoyang, J. Collateral damage of neonicotinoid insecticides: Unintended effects on gut microbiota of non-target organisms. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 2025, 298, 110330. doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpc.2025.110330.

- Rivi, V.; Pele, G.; Yakubets, K.; Batabyal, A.; Dominici, R.; Blom, J.M.C.; Tascedda, F.; Benatti, C.; Lukowiak, K. Effects of neonicotinoid and diamide-contaminated agricultural runoff on Lymnaea stagnalis: Insights into stress, neurotoxicity, and antioxidant response. Aquat Toxicol 2025, 287:107535. [CrossRef]

- Roman, P.; Cardona, D.; Sempere, L.; Carvajal, F. Neurotoxicology 2019, 75:200-208. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Qi, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, R.; Xiang; L.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, C.; et al. et al. Oxidative stress gene expression, DNA methylation, and gut microbiota interaction trigger Crohn's disease: a multi-omics Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med 2023 ,21(1):179. [CrossRef]

- Alula, K.M.; Dowdell, A.S.; LeBere, B.; Lee, J.S.; Levens, C.L.; Kuhn, K.A.; Kaipparettu, B.A.; Thompson, W.E.; Blunberg, R.S.; Colgan, S.P.; Theiss, A.L. Interplay of gut microbiota and host epithelial mitochondrial dysfunction is necessary for the development of spontaneous intestinal inflammation in mice. Microbiome 2023, 11(1):256. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhan, J.; Liu, D.; Luo, M.; Han, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, P. Organophosphorus pesticide chlorpyrifos intake promotes obesity and insulin resistance through impacting gut and gut microbiota. Microbiome 2019, 7(1):19. [CrossRef]

- Abou Diwan, M.; Djekkoun, N.; Boucau, M.C.; Dehouck, L.; Biendo, M.; Gosselet, F.; Bach, V.; Cnadela, P.; Khorsi-Cauet, H. Maternal exposure to pesticides induces perturbations in the gut microbiota and blood-brain barrier of dams and the progeny, prevented by a prebiotic. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2024, 31(49):58957-58972. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.; Bellinger, D.C.; Birnbaum, L.S.; Bradman, A.; Chen, A.; Cory-Slechta, D.A.; Engel, S.M.; Fallin, S.D.; Halladay, A.; Hauser, R.; et al. Project TENDR: Targeting Environmental Neuro-Developmental Risks The TENDR Consensus Statement. Environ Health Perspect 2016, 124(7):A118-A122. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Public health impact of pesticides used in agriculture. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int.

- Galarza, C.R.; Cruz, P.G. Guía para realizar estudios de revisión sistemática cuantitativa. CienciAmérica 2024, 13(1), 1-6.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).