1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for nearly 19 million deaths each year [

1]. Despite substantial advances in preventive and therapeutic strategies, a significant proportion of patients continues to experience adverse cardiovascular events, highlighting the persistence of residual cardiovascular risk. Over recent decades, the global burden of cardiometabolic disease has increased markedly, driven largely by the rising prevalence of obesity and its metabolic consequences [

2]. In parallel, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the most common manifestation of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), has emerged as a highly prevalent condition, particularly among individuals with obesity and patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [

3]. At the same time, advances in cardiovascular imaging have facilitated the recognition of epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) as an active biological compartment rather than a passive fat depot [

4], with population-based data demonstrating a progressive increase in EAT burden over recent decades in parallel with obesity rates [

5].

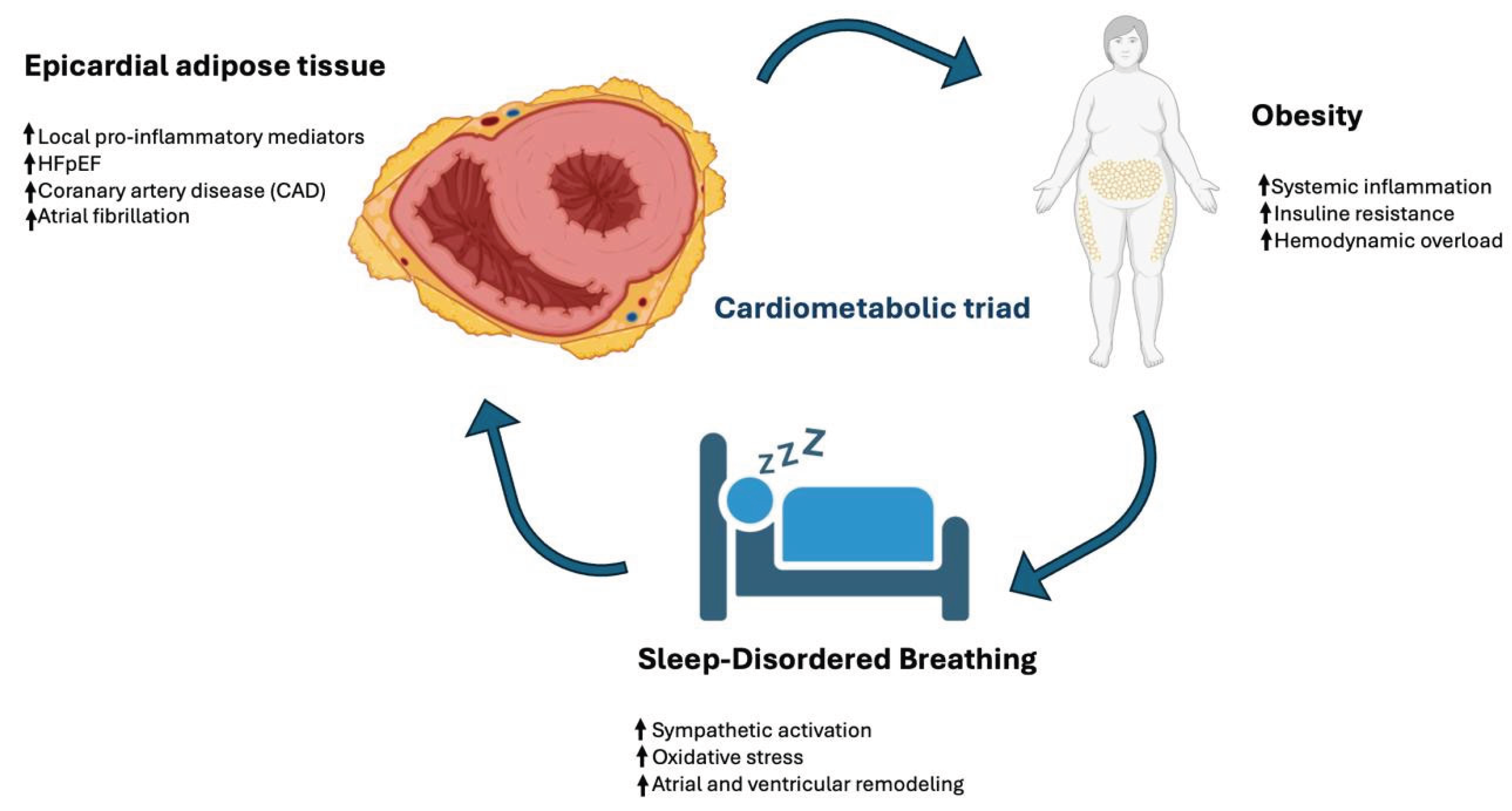

These three conditions—obesity, SDB, and EAT—are increasingly understood as interconnected components of a cardiometabolic continuum rather than isolated risk factors [

6].

Each exerts independent effects on cardiovascular structure and function; however, their coexistence appears to amplify myocardial injury, diastolic dysfunction, and arrhythmogenic remodeling, accelerating the development of HFpEF, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease [

7]. Importantly, these conditions contribute to mechanisms of cardiovascular risk that are not fully addressed by conventional therapies, providing a plausible biological basis for residual cardiovascular risk [

8,

9]. Obesity promotes chronic low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, and hemodynamic overload, while simultaneously favoring SDB and EAT expansion [

10]. In turn, SDB introduces recurrent intermittent hypoxia and sympathetic activation, further aggravating metabolic dysregulation and adipose tissue dysfunction [

11,

12].

Within this framework, EAT emerges as a critical biological interface linking systemic metabolic disturbances to local myocardial and vascular injury. Through its pro-inflammatory and profibrotic secretome, EAT may mediate adverse cardiac remodeling and contribute to the development of atrial fibrillation, coronary atherosclerosis, and HFpEF. The reciprocal interactions among obesity, SDB, and EAT define a distinct high-risk cardiometabolic phenotype increasingly encountered in clinical practice (

Figure 1).

Importantly, inter-individual variability in inflammatory signaling, adipose tissue biology, and cardiometabolic susceptibility suggests that this phenotype may represent a biologically heterogeneous entity rather than a uniform clinical condition. At the same time, emerging therapies—including sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA), and dual incretin agonists such as tirzepatide—have demonstrated the potential to favorably modulate multiple components of this pathological network [

13,

14,

15].

By framing obesity, SDB, and EAT as an integrated cardiometabolic system, this review aims to synthesize current evidence on their shared pathophysiological pathways and cardiovascular consequences, highlighting opportunities for improved phenotypic stratification and more comprehensive therapeutic strategies in cardiometabolic disease.

2. Obesity and Its Cardiometabolic Impact

Obesity is not merely a condition of excess body weight but a complex disorder characterized by profound alterations in adipose tissue biology and systemic metabolic regulation [

16]. Hypertrophic and dysfunctional adipocytes exhibit a pro-inflammatory phenotype, releasing cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α while downregulating protective adipokines, including adiponectin [

17]. This imbalance promotes a state of chronic low-grade inflammation—often referred to as metaflammation—that contributes to insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, and vascular stiffness, thereby accelerating atherosclerosis and adverse cardiac remodeling. These systemic alterations also favor the disproportionate expansion of visceral fat depots, including EAT, linking obesity directly to local cardiac injury [

18].

Excess adiposity is strongly associated with SDB, particularly OSA. Fat accumulation in the upper airway and surrounding structures reduces airway patency and impairs neuromuscular control, explaining why body mass index remains one of the strongest predictors of SDB severity [

19]. Importantly, this relationship is bidirectional: intermittent hypoxia and sympathetic activation associated with SDB worsen metabolic control and promote further weight gain, establishing a self-reinforcing pathological loop [

20].

The cardiovascular consequences of obesity extend beyond traditional risk factors. Large-scale analyses demonstrate a robust association between increasing body mass index and atrial fibrillation, with a linear rise in risk across weight categories [

21]. Similarly, obesity represents one of the strongest predictors of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, with population-based studies reporting hazard ratios consistently exceeding those observed for many traditional cardiovascular risk factors [

22,

23]. These observations support the concept that obesity orchestrates a convergence of metabolic, inflammatory, and hemodynamic stressors that promote diastolic dysfunction, atrial remodeling, and arrhythmogenesis [

24,

25].

From a therapeutic perspective, obesity is increasingly recognized as a modifiable upstream determinant of cardiometabolic disease. Lifestyle-induced weight reduction has been shown to improve diastolic function, reduce atrial fibrillation burden, and decrease EAT thickness [

26]. Pharmacological strategies capable of achieving more substantial weight loss, including glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dual incretin agonists such as tirzepatide, produce marked reductions in visceral adiposity and are associated with favorable changes in cardiac structure and function [

27,

28,

29]. Sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors further contribute to cardiovascular protection, partly through effects on ectopic fat depots and systemic inflammation [

30]. Notably, the SELECT trial provided definitive evidence that treating obesity itself reduces major adverse cardiovascular events, establishing obesity as a causal and therapeutically actionable driver of cardiovascular risk [

31].

Collectively, these findings position obesity as a central upstream component of the cardiometabolic triad. By promoting both SDB and EAT expansion and independently increasing susceptibility to atrial fibrillation and HFpEF, obesity defines a biological substrate that shapes a high-risk cardiometabolic phenotype.

3. Sleep-Disordered Breathing

SDB represents a central component of the cardiometabolic triad, positioned at the intersection between obesity-related metabolic dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Among its clinical phenotypes, OSA is the most prevalent and is strongly associated with excess adiposity [

32]. In individuals with obesity, fat deposition in the upper airway and surrounding soft tissues reduces pharyngeal lumen size and impairs neuromuscular control, predisposing to recurrent airway collapse during sleep [

33]. Each obstructive event initiates a cascade of pathophysiological responses—including intermittent hypoxia, reoxygenation injury, intrathoracic pressure swings, and sympathetic activation—that exert systemic and cardiac effects extending well beyond nocturnal breathing disturbances [

34] (

Figure 2).

At the cardiometabolic level, intermittent hypoxia promotes oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and metabolic dysregulation, thereby aggravating insulin resistance and adipose tissue inflammation [

35]. These mechanisms contribute to structural and functional cardiac remodeling through oxidative stress, autonomic imbalance, and inflammation-driven myocardial injury, including atrial enlargement, myocardial fibrosis, and impaired ventricular relaxation, creating a substrate for atrial fibrillation and HFpEF [

36]. When SDB coexists with expanded and inflamed EAT, the combined paracrine and neurohumoral milieu further amplifies myocardial injury and coronary atherosclerosis [

37]. Clinically, this overlap is common, with a high prevalence of OSA observed in patients with HFpEF and other forms of heart failure, reflecting shared pathophysiological drivers [

38].

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) remains the standard therapy for OSA, effectively reducing airway obstruction and nocturnal hypoxemia [

39]. However, large randomized trials have failed to demonstrate consistent reductions in major cardiovascular events, largely due to limited long-term adherence [

40,

41]. As a result, attention has shifted toward pharmacological strategies capable of modulating upstream cardiometabolic mechanisms. SGLT2i may indirectly reduce SDB severity through effects on visceral fat, fluid redistribution, and sympathetic tone [

42], while neurohormonal modulation with angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors has been associated with improvements in apnea severity in heart failure populations [

43]. More recently, substantial weight loss achieved with GLP-1RA and dual incretin agonists such as tirzepatide has been shown to significantly improve OSA severity, supporting the concept that targeting obesity-related mechanisms may modify the downstream consequences of SDB [

44,

45].

Taken together, these findings support the view that SDB is not merely a comorbidity but an active pathophysiological mediator within the cardiometabolic triad. Its contribution to cardiovascular remodeling appears to be tightly linked to metabolic dysfunction, adipose tissue inflammation, and autonomic imbalance, reinforcing the need for integrated strategies that address the shared biological substrates underlying cardiometabolic disease.

4. Epicardial Adipose Tissue

EAT has evolved from being regarded as a passive fat depot to a metabolically active organ with direct implications for cardiovascular structure and function [

46]. Located between the visceral pericardium and the myocardium, EAT shares the coronary blood supply and exhibits direct anatomical continuity with the underlying heart and coronary arteries [

47]. This unique localization enables close biological interaction with adjacent tissues, allowing EAT-derived mediators to influence myocardial and vascular biology through paracrine and vasocrine signaling [

48]. Under physiological conditions, EAT contributes to myocardial energy homeostasis and thermoregulation [

49]. In obesity and cardiometabolic disease, however, EAT expands in volume and undergoes a phenotypic shift toward a pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic state [

50].

Pathological EAT is characterized by an altered secretome, with increased release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and reduced secretion of protective adipokines [

51]. These changes promote myocardial fibrosis, impair diastolic relaxation, and increase arrhythmogenic susceptibility, particularly at the atrial level [

52]. Pericoronary EAT further contributes to atherosclerosis and plaque vulnerability through localized inflammatory signaling, reinforcing the link between adipose tissue dysfunction and coronary artery disease [

53]. Clinically, increased EAT burden has been consistently associated with atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction [

54].

Advances in cardiovascular imaging have enabled the non-invasive quantification of EAT, facilitating its integration into clinical and research settings. Transthoracic echocardiography allows simple measurement of EAT thickness, with values exceeding 5 mm associated with increased cardiovascular risk [

55] (

Figure 3). Computed tomography provides accurate volumetric assessment and demonstrates strong correlations between EAT burden, coronary calcification, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes [

56]. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is considered the reference standard for EAT quantification, offering high spatial resolution and the ability to simultaneously assess myocardial structure and function, although its routine use is limited by cost and availability [

57].

Beyond risk stratification, EAT is increasingly recognized as a modifiable therapeutic target. Weight reduction achieved through lifestyle interventions is associated with significant decreases in EAT thickness and improvements in cardiac function [

58,

59,

60]. Pharmacological therapies, including glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors, have demonstrated consistent reductions in EAT volume alongside favorable metabolic and inflammatory effects [

61,

62]. Emerging data suggest that regression of EAT may reflect broader improvements in cardiometabolic health, although definitive evidence linking EAT reduction to improved clinical outcomes remains limited [

63].

Collectively, these findings support the role of EAT as a key biological mediator within the cardiometabolic triad. By linking systemic metabolic dysfunction to local myocardial and vascular injury, EAT contributes to a distinct cardiometabolic phenotype characterized by structural remodeling and heightened cardiovascular risk.

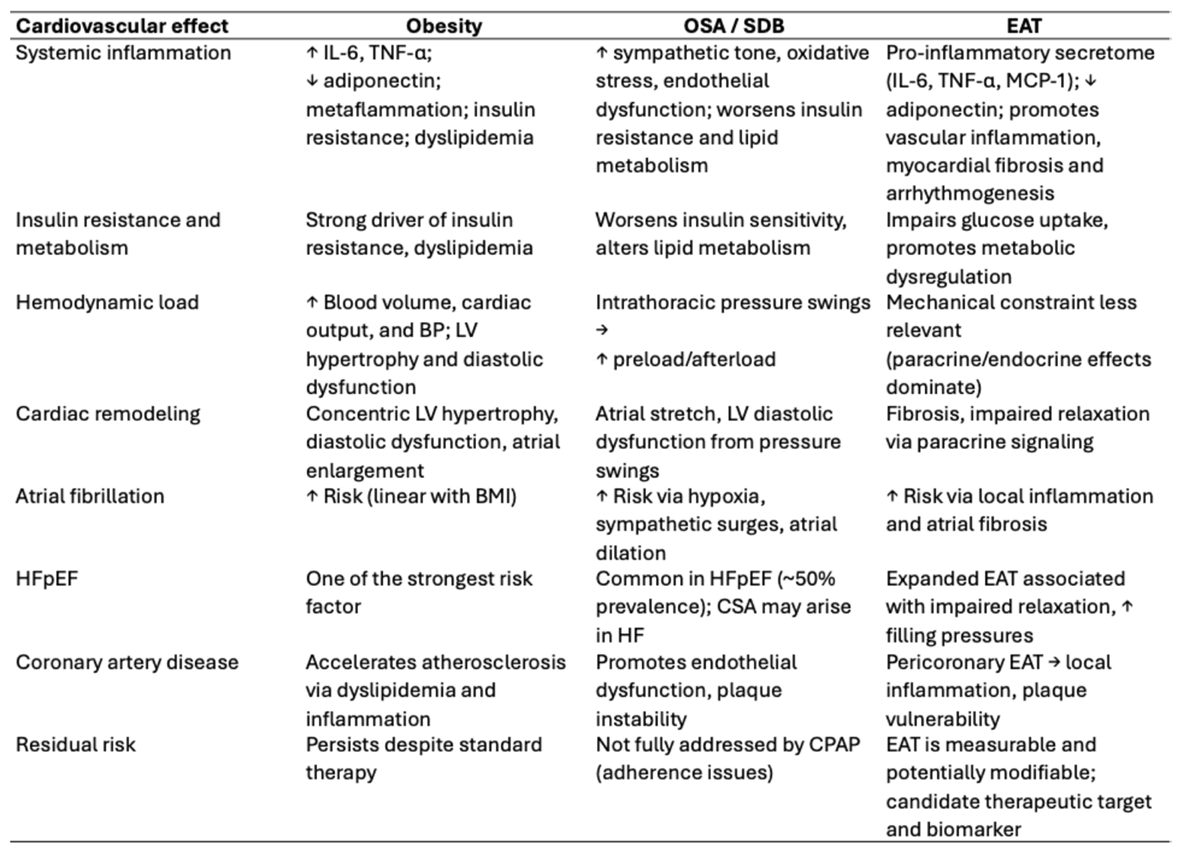

The main pathophysiological mechanisms and cardiovascular consequences associated with obesity, SDB, and EAT are summarized in

Table 1.

5. Therapeutic Limitations and Future Directions

The recognition of obesity, SDB, and EAT as an interconnected cardiometabolic triad provides a compelling framework for integrated prevention and treatment strategies; however, several therapeutic limitations remain. Current guideline-directed cardiovascular therapies primarily target downstream manifestations of disease, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and ischemia, while leaving upstream metabolic and inflammatory substrates largely unaddressed. As a result, residual cardiovascular risk persists despite optimal standard care.

Over the past decade, pharmacological agents with pleiotropic metabolic effects—particularly sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists—have demonstrated consistent benefits across a range of cardiometabolic conditions, including reductions in visceral and epicardial fat and improvements in cardiovascular outcomes [

64]. The emergence of dual incretin agonists such as tirzepatide, and the development of next-generation multi-agonist compounds, further expand the therapeutic landscape by targeting multiple metabolic and neurohumoral pathways simultaneously [

65,

66]. Nevertheless, the long-term cardiovascular safety, cost-effectiveness, and generalizability of these agents across diverse patient populations require further evaluation.

Important gaps in evidence also persist. Most data linking EAT burden to adverse cardiovascular outcomes derive from observational studies or relatively small interventional cohorts, limiting causal inference. Similarly, large randomized trials of continuous positive airway pressure therapy in SDB have failed to demonstrate consistent reductions in major cardiovascular events, likely reflecting suboptimal adherence and patient heterogeneity. Although newer metabolic therapies improve surrogate markers such as EAT volume and apnea severity, it remains uncertain whether these changes translate into sustained reductions in atrial fibrillation recurrence, heart failure progression, or coronary events.

Future research should prioritize outcome-driven trials that integrate metabolic, respiratory, and cardiovascular endpoints, rather than focusing on single-disease frameworks. Advances in cardiovascular imaging and biomarker discovery may enable refined phenotypic stratification, identifying patients most likely to benefit from targeted interventions. Ultimately, disrupting the cardiometabolic triad will require a shift toward personalized, multimodal strategies that address shared biological pathways underlying obesity, SDB, and EAT, thereby moving from risk recognition to effective risk modification.

6. Conclusions

The convergence of obesity, sleep-disordered breathing, and epicardial adipose tissue defines a cardiometabolic triad that contributes to cardiovascular remodeling through interconnected metabolic, inflammatory, and neurohumoral mechanisms. Rather than acting as isolated comorbidities, these conditions reinforce one another, promoting myocardial fibrosis, diastolic dysfunction, atrial remodeling, and coronary atherosclerosis, thereby sustaining residual cardiovascular risk despite guideline-directed therapy.

Within this framework, epicardial adipose tissue emerges as a key biological interface linking systemic metabolic dysfunction to local cardiac and vascular injury. Its close anatomical proximity to the myocardium and coronary arteries, coupled with its pro-inflammatory secretome in pathological states, supports its role as both a mediator of disease and a potential marker of cardiometabolic risk. Similarly, sleep-disordered breathing amplifies metabolic and autonomic disturbances, further aggravating adipose tissue dysfunction and cardiac remodeling.

The cardiometabolic triad should therefore be regarded as a distinct high-risk phenotype rather than a coincidental clustering of conditions. This conceptual shift has important clinical implications, suggesting that effective cardiovascular risk reduction may require integrated strategies targeting excess adiposity, sleep-related pathophysiology, and adipose tissue biology simultaneously. Emerging metabolic therapies and advances in cardiovascular imaging offer promising tools to address these shared pathways, although robust outcome-driven evidence remains limited.

In conclusion, recognizing obesity, sleep-disordered breathing, and epicardial adipose tissue as components of a unified cardiometabolic system provides a pathophysiological basis for improved phenotypic stratification and more comprehensive approaches to cardiovascular disease prevention and management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Fu.Ca.; methodology, Fu.Ca. and G.C.; validation, Fu.Ca., G.C., F.S., M.L, Fl.Ca.., M.R. and N.V.; formal analysis, Fu.Ca. investigation, Fu.Ca. and G.C.; resources, Fl.Ca..; data curation, Fu.Ca. and N.V..; writing—original draft preparation, Fu.Ca.; writing—review and editing, Fu.Ca..; visualization, Fl.Ca..; supervision, Fu.Ca..; project administration, Fu.Ca. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AF |

Atrial fibrillation |

| AHI |

Apnea-hypopnea index |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| CAD |

Coronary artery disease |

| CPAP |

Continuous positive airway pressure |

| CSA |

Central sleep apnea |

| EAT |

Epicardial adipose tissue |

| GLP-1RA |

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist |

| HFpEF |

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| MACE |

Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MCP-1 |

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| OSA |

Obstructive sleep apnea |

| SGLT2i |

Sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitor |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor-α |

References

- Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. Nov 2018;392(10159):1736–88.

- Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M, et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. Oct 2020;396(10258):1223–49.

- Esmaeili N, Gell L, Imler T, Hajipour M, Taranto-Montemurro L, Messineo L, et al. The relationship between obesity and obstructive sleep apnea in four community-based cohorts: an individual participant data meta-analysis of 12,860 adults. eClinicalMedicine. May 2025;83:103221. [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis G, Willens HJ. Echocardiographic Epicardial Fat: A Review of Research and Clinical Applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. Dec 2009;22(12):1311–9. [CrossRef]

- Wiszniewski K, Grudniewska A, Szabłowska-Gadomska I, Pilichowska-Paszkiet E, Zaborska B, Zgliczyński W, et al. Epicardial Adipose Tissue—A Novel Therapeutic Target in Obesity Cardiomyopathy. Int J Mol Sci. Aug 2025;26(16):7963. [CrossRef]

- Cacciapuoti F, Mauro C, Capone V, Sasso A, Tarquinio LG, Cacciapuoti F. Cardiometabolic Crossroads: Obesity, Sleep-Disordered Breathing, and Epicardial Adipose Tissue in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction – A Mini-Review. Heart Mind. Mar 2025;9(2):147–56. [CrossRef]

- Eisele HJ, Markart P, Schulz R. Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Oxidative Stress, and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence from Human Studies. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Rabkin SW. The Relationship Between Epicardial Fat and Indices of Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. Feb 2014;12(1):31–42. [CrossRef]

- Cacciapuoti F, Mauro C, D’Andrea D, Capone V, Liguori C, Cacciapuoti F. Epicardial adipose tissue and residual cardiovascular risk: a comprehensive case analysis and therapeutic insights with Liraglutide. J Cardiovasc Med. Aug 2024;25(8):637–41. [CrossRef]

- Zatterale F, Longo M, Naderi J, Raciti GA, Desiderio A, Miele C, et al. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Front Physiol. Jan 2020;10:1607. [CrossRef]

- Cacciapuoti F, D'Onofrio A, Tarquinio LG, Capone V, Mauro C, Marfella R, Cacciapuoti F. Sleep-disordered breathing and heart failure: a vicious cycle of cardiovascular risk. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2023 Sep 1;94(2). PMID: 37667884. [CrossRef]

- Ridker PM. Residual inflammatory risk: addressing the obverse side of the atherosclerosis prevention coin. Eur Heart J. Jun 2016;37(22):1720–2. [CrossRef]

- Masson W, Lavalle-Cobo A, Nogueira JP. Effect of SGLT2-Inhibitors on Epicardial Adipose Tissue: A Meta-Analysis. Cells. Aug 2021;10(8):2150. [CrossRef]

- Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, Deanfield J, Emerson SS, Esbjerg S, et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N Engl J Med. Dec 2023;389(24):2221–32. [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff AM, Aronne LJ, Ahmad NN, Wharton S, Connery L, Alves B, et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N Engl J Med. Jul 2022;387(3):205–16. [CrossRef]

- Welsh A, Hammad M, Piña IL, Kulinski J. Obesity and cardiovascular health. Eur J Prev Cardiol. Jun 2024;31(8):1026–35.

- Leo S, Tremoli E, Ferroni L, Zavan B. Role of Epicardial Adipose Tissue Secretome on Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomedicines. Jun 2023;11(6):1653. [CrossRef]

- Monti CB, Codari M, De Cecco CN, Secchi F, Sardanelli F, Stillman AE. Novel imaging biomarkers: epicardial adipose tissue evaluation. Br J Radiol. Sep 2020;93(1113):20190770. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz AR, Patil SP, Laffan AM, Polotsky V, Schneider H, Smith PL. Obesity and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches. Proc Am Thorac Soc. Feb 2008;5(2):185–92.

- Patel SR. Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Ann Intern Med. Dec 2019;171(11):ITC81–96. [CrossRef]

- Wanahita N, Messerli FH, Bangalore S, Gami AS, Somers VK, Steinberg JS. Atrial fibrillation and obesity—results of a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. Feb 2008;155(2):310–5. [CrossRef]

- Ho JE, Enserro D, Brouwers FP, Kizer JR, Shah SJ, Psaty BM, et al. Predicting Heart Failure With Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction: The International Collaboration on Heart Failure Subtypes. Circ Heart Fail. Jun 2016;9(6):e003116. [CrossRef]

- Pandey A, Omar W, Ayers C, LaMonte M, Klein L, Allen NB, et al. Sex and Race Differences in Lifetime Risk of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation. Apr 2018;137(17):1814–23. [CrossRef]

- Karimian S, Stein J, Bauer B, Teupe C. Improvement of impaired diastolic left ventricular function after diet-induced weight reduction in severe obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. Jan 2017;Volume 10:19–25. [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis G, Singh N, Wharton S, Sharma AM. Substantial Changes in Epicardial Fat Thickness After Weight Loss in Severely Obese Subjects. Obesity. Jul 2008;16(7):1693–7. [CrossRef]

- Cacciapuoti F, Caso I, Crispo S, Verde N, Capone V, Gottilla R, et al. Linking Epicardial Adipose Tissue to Atrial Remodeling: Clinical Implications of Strain Imaging. Hearts. Jan 2025;6(1):3. [CrossRef]

- Wilding JPH, Batterham RL, Calanna S, Davies M, Van Gaal LF, Lingvay I, et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N Engl J Med. Mar 2021;384(11):989–1002. [CrossRef]

- Kramer CM, Borlaug BA, Zile MR, Ruff D, DiMaria JM, Menon V, et al. Tirzepatide Reduces LV Mass and Paracardiac Adipose Tissue in Obesity-Related Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. Feb 2025;85(7):699–706. [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis G, Mohseni M, Bianco SD, Banga PK. Liraglutide causes large and rapid epicardial fat reduction. Obesity. Feb 2017;25(2):311–6. [CrossRef]

- Cowie MR, Fisher M. SGLT2 inhibitors: mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit beyond glycaemic control. Nat Rev Cardiol. Feb 2020;17(12):761–72. [CrossRef]

- Ryan DH, Lingvay I, Deanfield J, Kahn SE, Barros E, Burguera B, et al. Long-term weight loss effects of semaglutide in obesity without diabetes in the SELECT trial. Nat Med. Jul 2024;30(7):2049–57. [CrossRef]

- Bonsignore MR. Obesity and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2022;274:181-201. PMID: 34697666. [CrossRef]

- Deng H, Duan X, Huang J, Zheng M, Lao M, Weng F, et al. Association of adiposity with risk of obstructive sleep apnea: a population-based study. BMC Public Health. Sep 2023;23(1):1835. [CrossRef]

- Yeghiazarians Y, Jneid H, Tietjens JR, Redline S, Brown DL, El-Sherif N, Mehra R, Bozkurt B, Ndumele CE, Somers VK. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021 Jul 20;144(3):e56-e67. PMID: 34148375. Epub 2021 Jun 21. Erratum in: Circulation. 2022 Mar 22;145(12):e775. [CrossRef]

- Drager LF, Togeiro SM, Polotsky VY, Lorenzi-Filho G. Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J Am Coll Cardiol. Aug 2013;62(7):569–76.

- Wei H, Luo Y, Wei C, Liao H, Nong F. Cardiac structural and functional changes in OSAHS patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. Aug 2024;24(1):562. [CrossRef]

- Song G, Sun F, Wu D, Bi W. Association of epicardial adipose tissues with obstructive sleep apnea and its severity: A meta-analysis study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. Jun 2020;30(7):1115–20. [CrossRef]

- Monda VM, Gentile S, Porcellati F, Satta E, Fucili A, Monesi M, et al. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction and Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Novel Paradigm for Additional Cardiovascular Benefit of SGLT2 Inhibitors in Subjects With or Without Type 2 Diabetes. Adv Ther. NOv 2022;39(11):4837–46. [CrossRef]

- McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, Luo Y, Ou Q, Zhang X, et al. CPAP for Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. N Engl J Med. Sep 2016;375(10):919–31. [CrossRef]

- Furlow B. SAVE trial: no cardiovascular benefits for CPAP in OSA. Lancet Respir Med. Nov 2016;4(11):860. [CrossRef]

- Eguchi K, Yabuuchi T, Nambu M, Takeyama H, Azuma S, Chin K, et al. Investigation on factors related to poor CPAP adherence using machine learning: a pilot study. Sci Rep. Nov 2022;12(1):19563. [CrossRef]

- Tanriover C, Ucku D, Akyol M, Cevik E, Kanbay A, Sridhar VS, et al. Potential Use of SGLT-2 Inhibitors in Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A new treatment on the horizon. Sleep Breath. Mar 2023;27(1):77–89. [CrossRef]

- Jaffuel D, Nogue E, Berdague P, Galinier M, Fournier P, Dupuis M, et al. Sacubitril-valsartan initiation in chronic heart failure patients impacts sleep apnea: the ENTRESTO-SAS study. ESC Heart Fail. Aug 2021;8(4):2513–26. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra A, Grunstein RR, Fietze I, Weaver TE, Redline S, Azarbarzin A, et al. Tirzepatide for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Obesity. N Engl J Med. Oct 2024;391(13):1193–205. [CrossRef]

- Armentaro G, Pelaia C, Condoleo V, Severini G, Crudo G, De Marco M, et al. Effect of SGLT2-Inhibitors on Polygraphic Parameters in Elderly Patients Affected by Heart Failure, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and Sleep Apnea. Biomedicines. Apr 2024;12(5):937. [CrossRef]

- Packer M. Epicardial Adipose Tissue May Mediate Deleterious Effects of Obesity and Inflammation on the Myocardium. J Am Coll Cardiol. May 2018;71(20):2360–72. [CrossRef]

- Napoli G, Pergola V, Basile P, De Feo D, Bertrandino F, Baggiano A, et al. Epicardial and Pericoronary Adipose Tissue, Coronary Inflammation, and Acute Coronary Syndromes. J Clin Med. Nov 2023;12(23):7212. [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis G. Epicardial adipose tissue in contemporary cardiology. Nat Rev Cardiol. Sep 2022;19(9):593–606. [CrossRef]

- Chechi K, Richard D. Thermogenic potential and physiological relevance of human epicardial adipose tissue. Int J Obes Suppl. Aug 2015;5(S1):S28–34. [CrossRef]

- Rafeh R, Viveiros A, Oudit GY, El-Yazbi AF. Targeting perivascular and epicardial adipose tissue inflammation: therapeutic opportunities for cardiovascular disease. Clin Sci. Apr 2020;134(7):827–51. [CrossRef]

- Ansaldo AM, Montecucco F, Sahebkar A, Dallegri F, Carbone F. Epicardial adipose tissue and cardiovascular diseases. Int J Cardiol. Mar 2019;278:254–60. [CrossRef]

- Meulendijks ER, Al-Shama RFM, Kawasaki M, Fabrizi B, Neefs J, Wesselink R, et al. Atrial epicardial adipose tissue abundantly secretes myeloperoxidase and activates atrial fibroblasts in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Transl Med. Jun 2023;21(1):366. [CrossRef]

- Nerlekar N, Brown AJ, Muthalaly RG, Talman A, Hettige T, Cameron JD, et al. Association of Epicardial Adipose Tissue and High-Risk Plaque Characteristics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. Aug 2017;6(8):e006379. [CrossRef]

- Villasante Fricke AC, Iacobellis G. Epicardial Adipose Tissue: Clinical Biomarker of Cardio-Metabolic Risk. Int J Mol Sci. Nov 2019;20(23):5989.

- Eroglu S. How do we measure epicardial adipose tissue thickness by transthoracic echocardiography? Anatol J Cardiol. May 2015;15(5):416–9. [CrossRef]

- Dell’Aversana F, Tuccillo R, Monfregola A, De Angelis L, Ferrandino G, Tedeschi C, et al. Epicardial Adipose Tissue Volume Assessment in the General Population and CAD-RADS 2.0 Score Correlation Using Dual Source Cardiac CT. Diagnostics. Mar 2025;15(6):681. [CrossRef]

- Leo LA, Paiocchi VL, Schlossbauer SA, Ho SY, Faletra FF. The Intrusive Nature of Epicardial Adipose Tissue as Revealed by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. J Cardiovasc Echogr. 2019 Apr-Jun;29(2):45-51. [CrossRef]

- Venkateshvaran A, Faxen UL, Hage C, Michaëlsson E, Svedlund S, Saraste A, et al. Association of epicardial adipose tissue with proteomics, coronary flow reserve, cardiac structure and function, and quality of life in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: insights from the PROMIS-HFPEF study. Eur J Heart Fail. Dec 2022;24(12):2251–60. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Guo J, Li Y, Wang S, Wan K, Li W, et al. Increased epicardial adipose tissue is associated with left ventricular reverse remodeling in dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Diabetol. Dec 2024;23(1):447. [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Galdós L, Barba-Cosials J, Núñez-Córdoba JM. Association between echocardiographic epicardial adipose tissue and E/e′ ratio in obese adults. Acta Diabetol. Jan 2018;55(1):103–6. [CrossRef]

- Berg G, Barchuk M, Lobo M, Nogueira JP. Effect of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues on epicardial adipose tissue: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. Jul 2022;16(7):102562. [CrossRef]

- Bao Y, Hu Y, Shi M, Zhao Z. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce epicardial adipose tissue more than GLP -1 agonists or exercise interventions in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and/or obesity: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. Mar 2025;27(3):1096–112.

- Con E, Yilmaz A, Suygun H, Mustu M, Karadeniz FO, Kilic O, Ozer FS. The relationship between epicardial adipose tissue thickness and coronary artery disease progress. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2023;124(7):545-548. [CrossRef]

- Khawaja T, Nied M, Wilgor A, Neeland IJ. Impact of Visceral and Hepatic Fat on Cardiometabolic Health. Curr Cardiol Rep. Nov 2024;26(11):1297–307. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra A, Bednarik J, Chakladar S, Dunn JP, Weaver T, Grunstein R, et al. Tirzepatide for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea: Rationale, design, and sample baseline characteristics of the SURMOUNT -OSA phase 3 trial. Contemp Clin Trials. Jun 2024;141:107516. [CrossRef]

- Hankosky ER, Wang H, Neff LM, Kan H, Wang F, Ahmad NN, et al. Tirzepatide reduces the predicted risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and improves cardiometabolic risk factors in adults with obesity or overweight: SURMOUNT-1 post hoc analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. Jan 2024;26(1):319–28. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).