Introduction

The global outbreak of COVID-19, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, significantly disrupted daily life worldwide following its classification as a pandemic by the World Health Organisation in early 2020 [WH0, 2020,[

1]. While previous coronavirus epidemics—namely Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV)—had emerged in earlier decades, their societal and lifestyle impacts were comparatively small [Unwin, 2021, [

2]. At the initial stages of the COVID-19 crisis, there was limited understanding of the virus’s transmission dynamics and potential consequences, prompting governments to act swiftly to mitigate its spread and safeguard public health.

In response, the United Kingdom introduced a nationwide lockdown in March 2020, which persisted for approximately three months. Citizens were instructed to remain indoors except for essential activities such as purchasing groceries or seeking medical care. Non-essential businesses were mandated to close, and additional public health measures—including social distancing and mandatory face coverings in public spaces—were subsequently enforced. Comparable protective health measures were adopted by governments around the world.

People with heightened risk due to underlying health conditions, physical impairments, and age-related immune decline were categorised as vulnerable populations [DHSC, 2020,[

3]. These factors increased their susceptibility to severe complications and elevated mortality rates associated with COVID-19 infection [

4], Ayouni et al., 2021, see Levin et al., 2020]. The heightened risk of severe illness from the virus and strict social distancing measures led to disruptions in essential social connections, distancing older adults from family and community interactions. As a result, many individuals’ lifestyles and social interactions were put on hold. These changes had been exacerbated by a rise in ageism, with prejudiced attitudes regarding the narrative of older adults’ vulnerability and restrictive measures directed at them [Levin et al., 2020, [

5]. For instance, policies stating that individuals aged 70 should not meet anyone or were legally prohibited from leaving their homes were implemented in the UK and globally [

5], Swift & Chasteen, 2021, [

6].

The swift global spread of the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus, along with its initially uncertain effects on human health and the high mortality rates observed in the early weeks of the pandemic, instilled widespread fear and panic across the world [Unwin, 2021, [

2]; Derrer-Merk et al.,, 2023,[

7]; Anwar et al., 2020,[

8]. Moreover, the protective health measures aimed to stop the spread of the virus also influenced people’s well-being by increasing social isolation and perceived loneliness [Agrawal et al., 2021,[

9],Jain &Dhall,2025, [

10], stress and anxiety across the population due to fears of infection, concerns about the health of loved ones, grief from loss, and the uncertainty caused by the pandemic [Yang, F., & Gu, 2025,[

11].

This study was motivated by the unprecedented nature of the pandemic and early signs that indicated a heightened risk for older adults. Its primary objective was to investigate the lived experiences of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a particular focus on the psychological and societal impacts of the health crisis. The study aimed to identify new, evidence-based insights into these challenges faced by older adults.

To our knowledge, little was known about older adults’ experiences at the onset of the health crisis [Lagacé etal., 2024,[

12]. This gap in research emphasised the urgent need for theory development addressing the well-being of older adults during a health crisis, as recently suggested by Klausen (2020; see also Biggs et al., 20021; Kim et al., 2021; Paltasingh, 2015). [

14,

15,

16]

Navigating Gerontological Theory Development

Over the past few decades, numerous theories in gerontology have emerged, exploring various aspects of ageing. Early theories focused on biological and neurological changes (Harman, 1956, 2006; Peters, 2006)[

17,

18,

19]. These theories evolved to consider societal and environmental influences (Havighurst, 1973; Lawton, 1983; Wahl et al., 2012)[

20,

21,

22]. Moreover, attention has shifted to critical gerontology perspectives (Estes et al., 1992; Baars et al., 2006; Bernard & Scharf, 2007; Hendricks & Achenbaum, 1999) [

23,

24,

25,

26] and, importantly, to psychological development and cognition among other areas (Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Carstensen, 2006; An, 2023)[

27,

28,

29].

These research areas collectively suggest that existing theories must evolve to better reflect the interrelated and multifaceted nature of ageing, particularly as our understanding of the interplay between psychological, biological, social, and technological factors deepens. This is of particular interest in times of health crises, as Feliciano et al. (2022) [

30] suggested in their development of resilience theory (see also Biggs et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2021; Paltasingh, 2015) [

13,

15,

16]. In general, developing gerontological theories advances gerontological knowledge and enriches our scientific understanding of how people in later life experience events like the COVID-19. This new knowledge can inform decision-making strategies, ultimately enhancing the well-being of older adults during health crises and beyond. This study developed a substantive

Ecological Theory of Older adults Well-Being during the COVID-19 pandemic, as a starting of theory development.

Well-Being Discourse

Well-being, recognised as a vital aspect of human life, influences many domains, regardless of the ongoing debates about its definition (Jarden & Roache, 2023) [

38]. Exploring well-being in the context of a pandemic is essential for a deeper understanding and being better prepared for future health crises (Kim et al., 2021)[

16]. Historically, theoretical discussions on well-being have been shaped by two contrasting perspectives: the hedonic and the eudaimonic approaches. Hedonic well-being centers on the pursuit of pleasure and immediate gratification, pointing towards experiences that elicit happiness and satisfaction in the present moment (Diener et al., 1999; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryff, 1989)[

39,

40,

41]. In contrast, eudaimonic well-being extends beyond transient pleasures, focusing on living a life of virtue, purpose, and personal growth. It underscores the importance of fulfilling one’s potential and cultivating a meaningful existence (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryff, 1989)[

40,

41].

A universally accepted definition of well-being might not be achievable soon but generally includes contentment in key life areas such as occupational fulfilment, positive emotions, a sense of purpose, and overall life satisfaction, which is often reflected in the quality of social relationships (Diener, 2000; Ryff & Keyes, 1995)[

42,

43]. While scholarly debates persist regarding the theoretical validity and applicability of these frameworks as discussed above, this study seeks to deepen understanding of older adults’ lived experiences in order to better inform preparedness for future health crises. We address these challenging circumstances by asking the following research question:

How can the lived experiences of older adults during a pandemic contribute to theory development and inform public health policies for future health crises and address their unique needs?

Research Context and Analytical Approach

This research study adopts a qualitative approach, specifically employing constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014)[

35], to examine the psychological and societal experiences of older adults. The authors aim to gain a deeper understanding of older adults’ experiences during the health crisis while also contributing to the development of theory, as advocated by Klausen (2020)[

14]. Constructivist grounded theory is considered the most suitable method for this study because it allows for the creation of new knowledge and theoretical frameworks, acknowledging the subjective interpretive nature, to understand previously unexplored phenomena. Additionally, it ensures a nuanced, systematically rigorous, and reflective interpretation of the findings (Charmaz, 2014)[

35]. It is an iterative data collection and analysis process that applies inductive, deductive, and abductive reasoning to data analysis. The constant comparison strategy of data analysis informs theoretical sampling, leading to theoretical saturation or sufficiency (Charmaz, 2014; Dey, 2003)[

35,

44].

Importantly, this study is part of a

doctoral thesis and offers a detailed account of the research interest, influencing factors, and procedures. It includes a concise overview of the applied methodology of theory development, the role of

sensitising concepts in guiding the inquiry, and the resulting

theoretical framework. For further details, see Derrer-Merk (2025)[

45]. Furthermore, this study forms part of a broader research initiative—the C19PRC project (COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium Study | COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium Study | The University of Sheffield) [

46]. As such, there may be similarities in aspects such as methodology, context, ethical approvals, analysis, and participant quotations. These overlaps are expected and reflect standard practices within large-scale, ongoing research programs like the C19PRC consortium. Importantly, the study acknowledges and cites the original sources to ensure transparency and address any potential concerns regarding duplication. By clearly referencing prior work and using quotation marks when using participant quotes, the authors maintain academic integrity and demonstrate responsible research conduct.

Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC)

In March 2020, the Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC, UK, C19PRC,

https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/psychology-consortium-covid19), led by Prof. Richard Bentall (R.P.B.), launched a nationally representative internet-based panel survey to examine the psychological, social, and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic (McBride et al., 2021)[

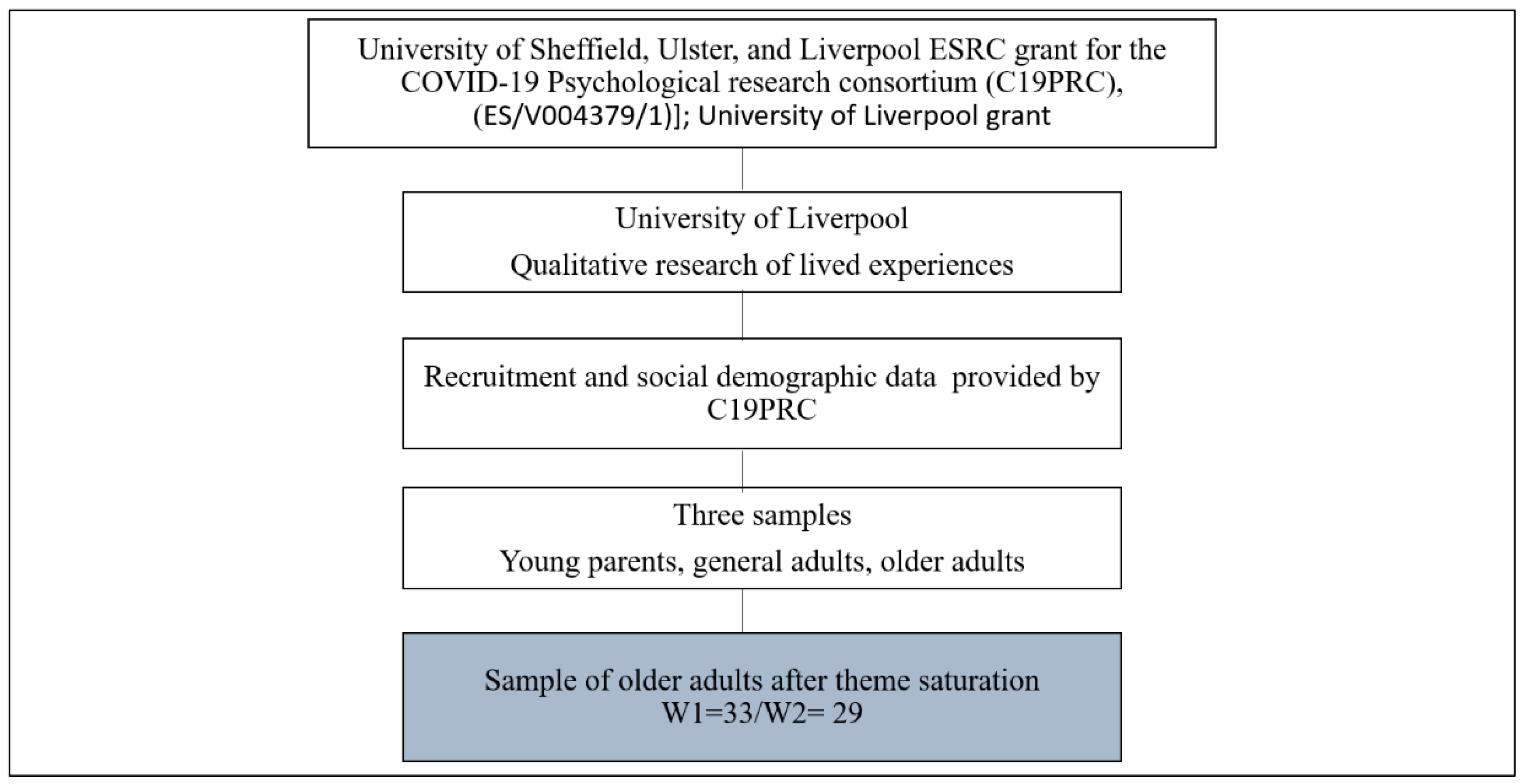

46]. The study sought high-quality evidence for policymakers and clinicians to navigate the evolving crisis. Simultaneously, researchers at the University of Liverpool, led by Prof Kate M Bennett (kmb), conducted a qualitative add-on study based on this national representative sample to explore adults’ lived experiences during the pandemic. This study’s first and last authors oversaw the entire qualitative data management process, designing the research process, including recruitment, data collection, and analysis. The first author’s qualitative research was particularly interested in older adults aged 65+, aiming to understand their unique experiences during the health crisis (see how this study is nested within the larger C19PRC project,

Figure 1). Our primary interest included examining changes in activities and emotional experiences at two-time points—at the pandemic’s onset (interview wave 1, W1) including 33 individuals (age range: 65–83, mean = 71, SD = 5) and one year later Wave 2 (W2) (

Figure 1) including 29 individuals (11 men, 18 women).

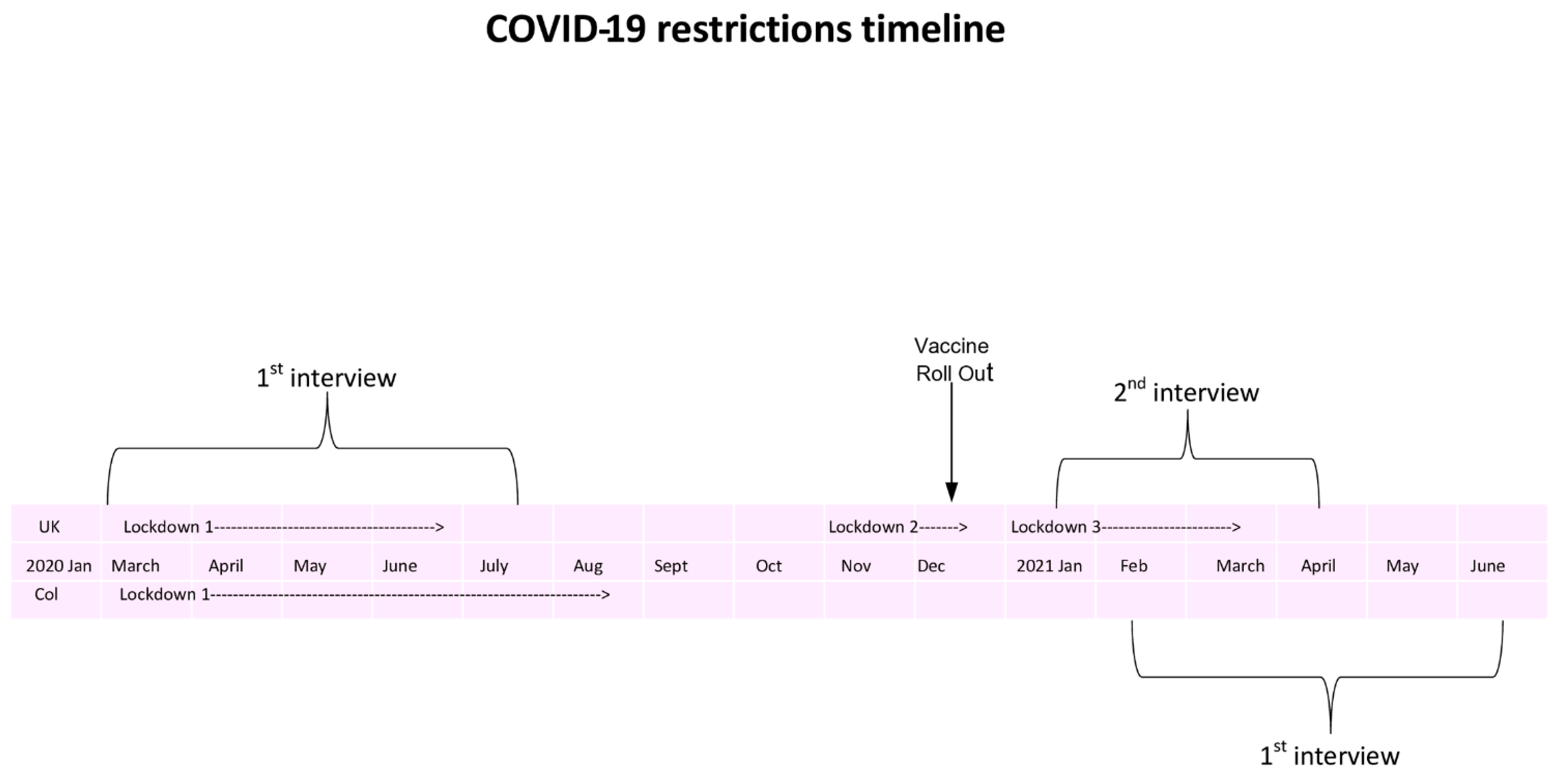

In collaboration with a colleague from Colombia (CO)(M-F R-R), we included data from 32 interviews aged 63–95 (16 men and 16 women, mean = 69, SD = 9) based on the same interview schedule and conducted from January to June 2021, enriching the study with culturally specific insights. Please see the timeline of the lockdown and the interview dates in

Figure 2. More details related to participants’ demographics can be seen in

Supplementary Material S1 Table S1.

Figure 2: Broad lockdown timeline for the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in both the UK and Colombia. Participants in the interviews reflected on the first year of the pandemic. Lockdown refers to the closure of all non-essential activities (shops, gyms, community centres etc.). Adults aged 70 and over were advised to stay at home and self-isolate, and in Colombia, it was mandatory (March-July 2020), the sanitariy emergency continued in Colombia until June 2022, where the use of masks was mandatory. Adapted from Derrer-Merk et al. (2025) [

47]

Applied Principles of Constructivist Grounded Theory

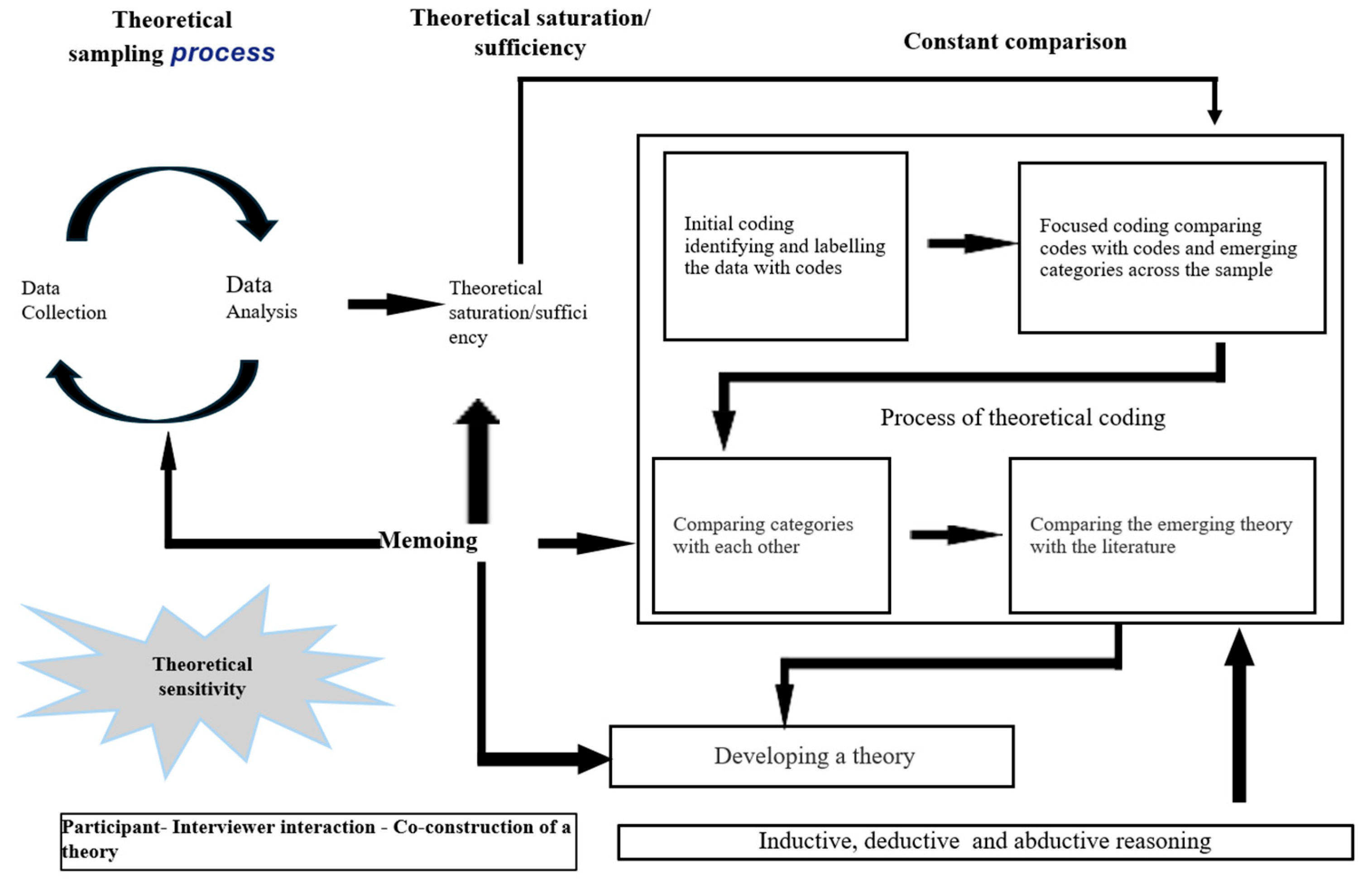

In this study, we use constructivist grounded theory (CGT), as mentioned above, that allows for the exploration of unknown phenomena. This approach acknowledges the researcher’s experiences and positionality, helping to develop new knowledge or theories aimed at gaining a deeper understanding of individual experiences. (Charmaz, 2014) [

35]. The analytical process was inductive and iterative, shaped by the researchers’ theoretical sensitivity—drawing on prior experience and emergent sensitising concepts (Blumer, 1969; Glaser, 1978) [

48,

49]. It involved theoretical sampling (within the iterative data collection and analysis process) and continued until theoretical sufficiency and saturation were reached. That is, the data provided sufficient depth of understanding, and no new insights were identified with new data collection, contributing to refining the theory (Dey, 2003; Vasileiou et al., 2018; Tight, 2023) [

44,

50,

51]. The established process of constant comparison data analysis was then applied to identify patterns, including similarities and differences across the data. Inductive, deductive and abductive reasoning supported the development of plausible explanations and higher-level abstractions (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) [

31]. Additionally, memoing—reflective writing and drawing—supported the process and is illustrated in

Figure 3 (Charmaz, 2014)[

35]. The process of theory development was supported by extensive discussions with the supervisor (KMB) and regular reflective dialogues with colleagues. The figure below illustrates the iterative process of theory development (adapted from Derrer-Merk et al., 2024)[

52].

These principles foster an iterative, adaptable, reflective research approach and support the co-construction (between data and researcher) of the meaning-making process of participants’ data, guided by the question, “What does this mean?” (Birks & Mills, 2023; Saldana, 2021)[

53,

54].

Furthermore, this study adhered to quality criteria (trustworthiness) suggested by Charmaz & Thornberg (2021)[

55]: credibility, originality, resonance, and usefulness. Trustworthiness was ensured by having sufficient data (credibility), new insights into older adults’ experiences during a pandemic (originality), and reflection of the experiences in theoretical concepts (resonance), and it illustrates a variety of dimensions to understand participants’ lived experiences (usefulness) (Charmaz & Thornberg, 2021) [

55]. Applying the principles of constructivist grounded theory fostered an elevated level of abstraction and led to a substantive theory.

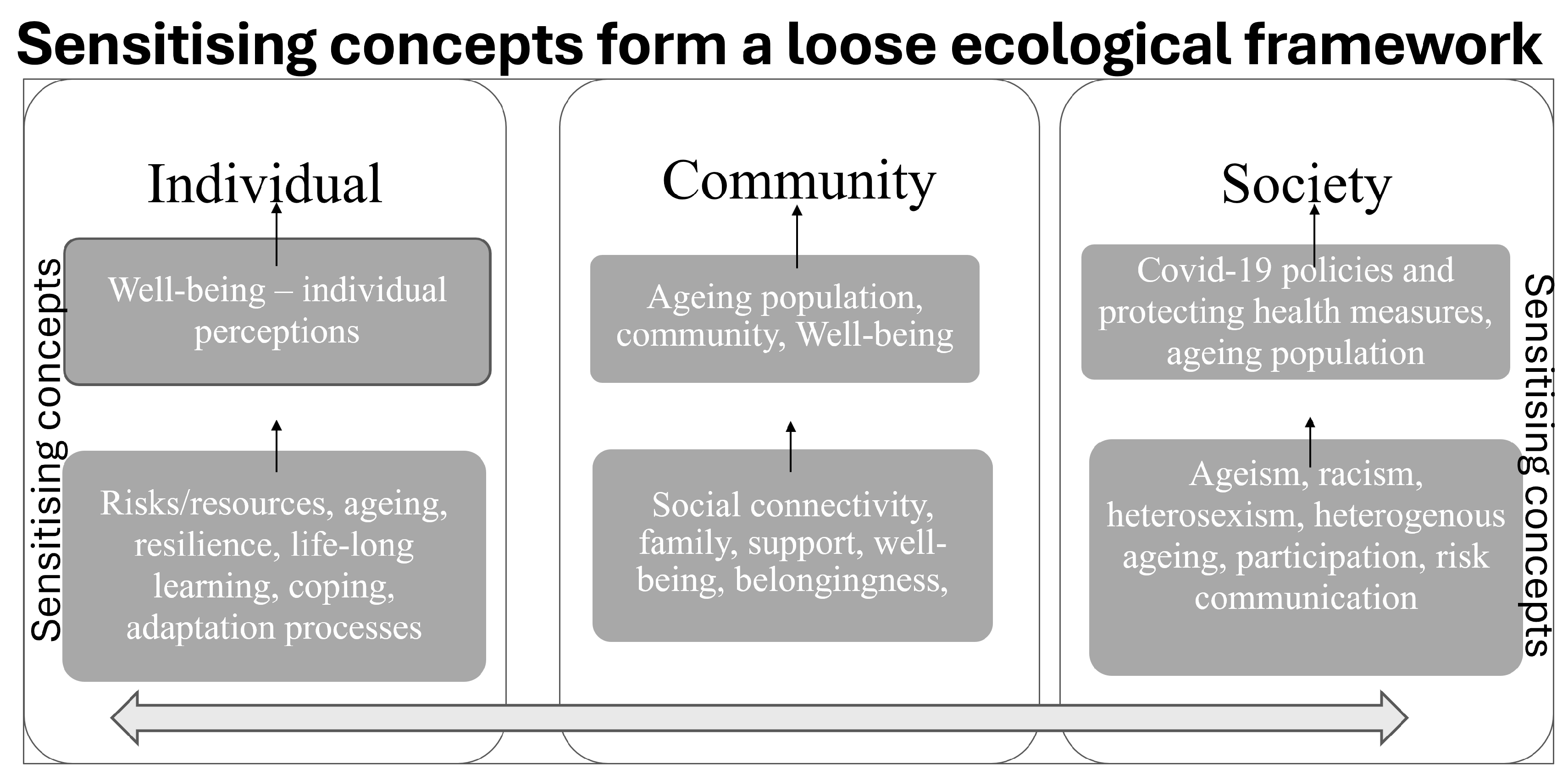

Analysis Guided by Sensitising Concepts

Constructivist grounded theory emphasises generating novel insights grounded in the data, guided by initial and emergent sensitising concepts (Charmaz, 2014)[

35]. Blumer (1969) [

48] suggested applying sensitising concepts over definitive concepts as the latter might impose the data into existing frameworks instead of exploring the data. These sensitising concepts offer a “general sense of what is relevant” (Blumer, 1969, p. 148, Bowen, 2006) [

48,

56] and serve as a flexible and open approach to where the data leads. Thus, an iterative analytical process allows theory to emerge from the data, continually adapting as new patterns and insights unfold during analysis. The initial sensitising concepts (theoretical concepts known to the researcher that guide inquiry) in this study consisted of healthy ageing, well-being, and resilience, along with the emergent sensitising concepts during the analysis, which supported the development of the theory, as illustrated in

Figure 5 within a loosely defined ecological framework.

This study found that the notion of healthy ageing—rooted in principles of equality and inclusivity—was not a dominant theme among participants. Instead, narratives were primarily centered on experiences of social distancing and lockdowns. References to healthy ageing were mostly in the context of stereotyping (vulnerability) and discrimination (Guo et al., 2022; Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, 2023)[

6,

47,

57]. Although resilience as advocated by Windle and Bennett (2011)[

58] was initially considered as a sensitising concept, the theme of well-being emerged more prominently. Participants often articulated well-being in everyday language, yet their descriptions aligned with ecological understandings of health and adaptation (Windle & Bennett, 2011)[

58]. Resilience became more apparent in discussions of belongingness and community cohesion (Derrer-Merk et al., 2022c; Windle and Bennett, 2011) [

58,

59]. The relationship between resilience and well-being is still a topic of debate (Schultze-Lutter et al., 2016) [

60]. However, data indicate that well-being—defined as the ability to adapt, experience a range of emotions, achieve life satisfaction, find purpose, and hold positive evaluations (Diener et al., 2009, 2010; Keyes, 1998; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Seligman & Peterson, 2003) [

43,

61,

62,

63]—emerged as a key finding. This suggests that resilience is one component within a larger framework that supports the well-being of older adults during the pandemic.

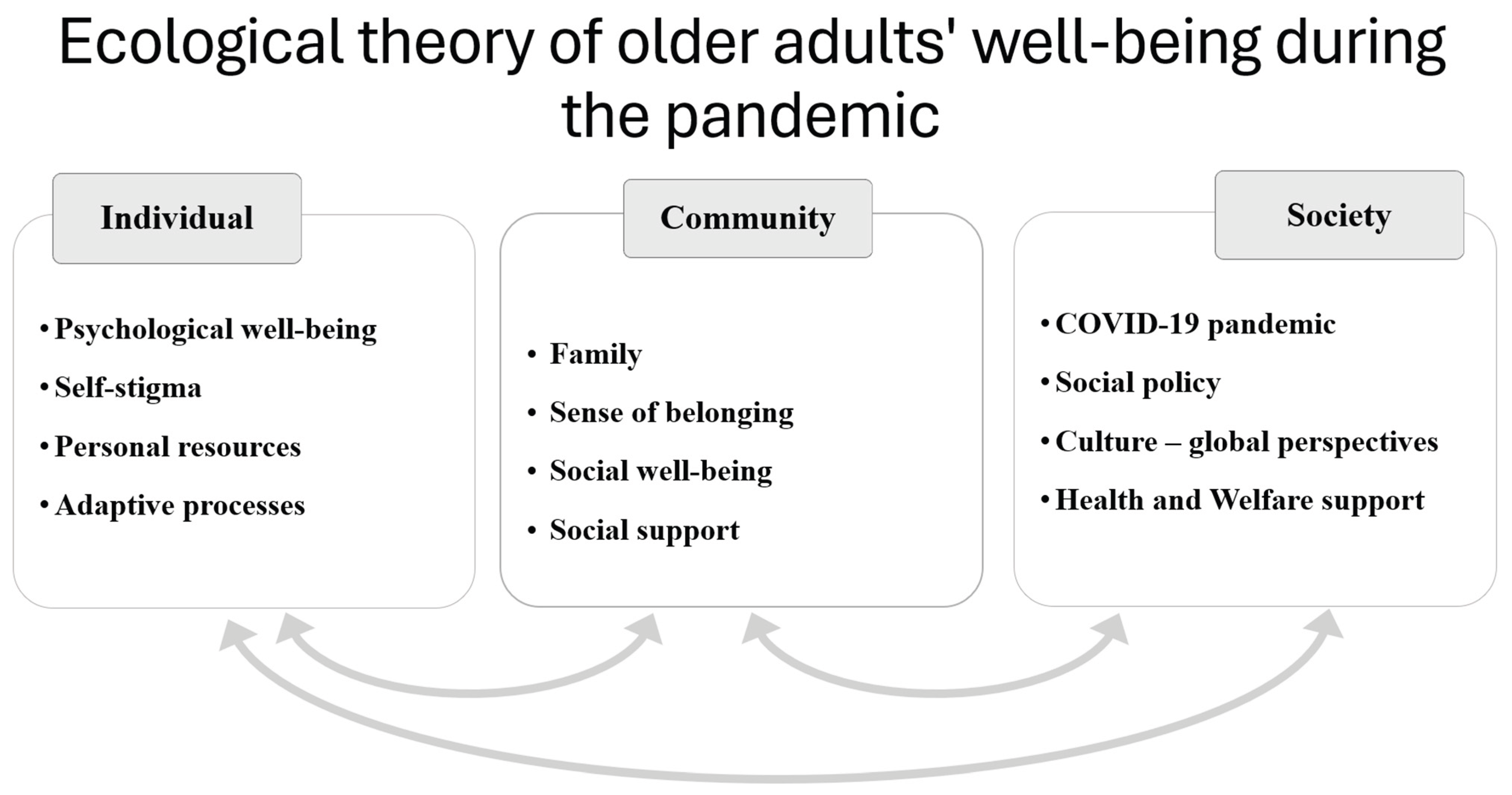

An Ecological Theory of Older Adults’ Well-Being

The analytical process undertaken in this study identified well-being as the most salient sensitising concept and the central theme emerging from the data. This underscores the profound impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological and social well-being of older adults. Although well-being lacks a universally accepted definition, our findings highlight its multifaceted nature. It includes elements like happiness and joy (Diener, 2009) [

61], especially during the pre-pandemic period. However, during the pandemic, there was a noticeable shift toward establishing new goals and finding purpose in life. Participants adapted to new circumstances through purposeful activities such as online teaching and learning, exercising, and reading, and sustained meaningful relationships that supported their well-being despite the constraints of social distancing (Derrer-Merk et al., 2022a, 2025, 2023; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Keyes, 1998)[

6,

43,

62,

64,

65].

Instrumental and emotional support—both experienced and perceived—from family and friends emerged as critical for maintaining well-being (Derrer-Merk et al., 2022a–d, 2023; Keyes, 1998; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Windle & Bennett, 2011).[

6,

43,

58,

62,

64,

65]. The analysis further revealed an ecological structure—serving as a sensitising concept—rooted in Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory and evolved through the contributions of Windle and Bennett (2011)[

58]. This approach highlights the foundational elements of older adults’ lives, including personal resources, family and social relationships, community support systems, and the influence of pandemic-related policies on their well-being. These interrelated dimensions are visually represented in

Figure 5.

The

Ecological Theory of Older Adults’ Well-Being highlights the dynamic interplay between individual, community, and societal factors. It demonstrates that well-being is developed through the interaction of personal capabilities, support systems, and social environments (Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Carstensen, 1995, 2021; House, 1982; Ivankina & Ivanova, 2016; Keyes, 1998; Ryff & Keyes, 1995; Uzuki et al., 2020)[

27,

43,

62,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. This interconnectedness will be explored further.

The following key quotes highlight the range of narratives, illustrating the diversity within the sample studied.

Individual Level

At the individual level, many participants talked about the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic but also demonstrated the ability to adapt after one year of the health crisis (Derrer-Merk et al., 2025, 2023)[

6,

65]. This capacity for coping and adjustment over time was evident across diverse national contexts (and diverse individual experiences), suggesting that it may represent a universal resource for sustaining well-being, irrespective of personal or cultural differences (see also Diener, 2009; Seligman & Peterson, 2003)[

61,

63]. Evidence is included from the UK and Colombia, as mentioned above:

“I tell you, I am a person who tries to handle things positively and when you are positive, nothing distresses you, nor does it make you sad.” (COSH03; Derrer-Merk et al., 2025, p.13)”[

65]

“Well, you’ve got to take the rough with the smooth, haven’t you? (…) I’ve started trying getting the attitude now that, look, bad things, possibly/probably are going to happen, but look at the tremendous health I’ve had up to now. Try and put a good spin on it.” (M10UKW2; Derrer-Merk et al., 2022d, p.13)[

65]

These narratives are an example, irrespective of individual backgrounds, many older adults consistently exhibited a capacity for adaptation, even when faced with varying levels of resources and diverse life experiences. This ability to adapt highlights the importance of recognising the role of broader social and cultural contexts in shaping coping and adaptation processes among older adults (Gilleard & Higgs, 2000; Henrich et al., 2023)[

71,

72].

For example, a participant from Colombia said:

“Right now the government has had a very important interest in the elderly (...) to avoid high mortality, and I think that if there has been more interest than before and it has made others think more about the older adults.” (CO SH04, Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, p. 911)[

73]

However, not all older adults adapted in the same way; some talked about the difficulties in navigating the challenges posed by the pandemic (Jarego et al., 2024)[

74]. For example, a woman from the UK mentioned:

“Yes, pretty miserable overall. I have to keep geeing myself along and saying oh come on, let’s do something productive, let’s do. . . It’s quite hard getting motivated.” (F1UKW2; Derrer-Merk et al., 2025, p.12)[

65]

Notably, many participants reported setting new goals during the lockdown, reflecting processes of meaning-making and the pursuit of purpose in life (Derrer-Merk et al., 2025)[

65]. Collectively, these aspects were essential resources that supported older adults in navigating the challenges of the pandemic and contributed to their overall well-being during a period of significant adversity (Baltes & Baltes, 1990).[

27], Many participants reflected on the prevailing societal narrative of vulnerability, often agreeing with the classification. However, this external labelling frequently led to shifts in self-perception, including altered self-authenticity and the internalisation of self-stigma. For instance, participant F16 UKW1 described the direct emotional impact of being officially categorised as ‘old’ by the UK government, noting how this designation influenced not only how she was perceived but also how she came to feel about herself.

“Well, reduced mobility because of arthritis, that made me feel old and also, I know this is before the lockdown, but as soon as the government told us that we were elderly, I felt it.” (F16 UK W1, Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, p. 914) [

73]

Others opposed the narrative, comparing their good health and fitness levels to younger generations. (Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, 2023)[

6,

73]. “I’ve always suffered from good health”. (M10 W2, Derrer-Merk, 2025. p. 485)[

65]

Participants who internalised the societal classification of vulnerability often curtailed their independence, which in turn posed challenges to their overall well-being. As one participant noted, this self-limitation emerged as a direct consequence of being labelled as vulnerable.:

“I can’t make myself go out, I’ll say that much now. I am literally too scared to go out”. (M8UK W1) (Derrer-Merk, 2025, p. 117)[

65]

This internalisation of self-stigma, which often resulted in self-restrictions, was also found earlier (see also Ayalon et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Naughton et al., 2021; Voinea et al., 2022)[

75,

76,

77,

78]. This finding underscores the dynamic interplay between individual, community, and societal levels during a health crisis, highlighting how these interconnected domains collectively shape experiences and responses.

Societal Level

The findings of this study, based on research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, are grounded in the societal level of the ecological framework of well-being (Derrer-Merk, 2025)[

65]. During the pandemic, public health measures focused on protecting those identified as vulnerable—primarily older adults aged 70 and above, and individuals with pre-existing medical conditions or non-communicable diseases. This classification was informed by early data showing that these groups were at greater risk of severe illness or mortality if infected with the virus. Hence, risk communication and societal perceptions have shifted in many countries towards viewing older adults as needing protection and support. This perspective contributed to a narrative that underestimated their autonomy and ability to make independent, informed decisions (DSHC, 2020; Ayalon & Tesch-Römer, 2018; Vasara et al., 2023)[

3,

75,

84]. CO SH02 told:

“Oh no, that you have to take care of them (older adults) (...), at this age one has more responsibility and one knows to care better than any 20-year-old kid (…) they annoyed me (…) (CO SH02, Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, p16).[

73]

Although well-intentioned, the classification of older adults as vulnerable led to paternalistic and age-based regulations. Many countries adopted this approach, which had already been subject to critical scrutiny (Ayalon, 2020; Ehni & Wahl, 2020; Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, 2023)[

65,

73,

75,

85].

Participants expressed mixed views on these regulations. While some perceived them as beneficial, others found them restrictive or even hostile. For example, one participant from the UK shared:

“I don’t think I fit the bill that needs to be cocooned yet. I possibly do medically, I don’t know, but I don’t mentally feel that I want to be cocooned. (M4W1UK, Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, p. 15).[

73]

In Colombia, initial mandatory regulations during the COVID-19 pandemic were perceived by some older adults as a form of increased societal recognition. However, this perception shifted over time, as older individuals were subjected to stricter limitations—such as being prohibited from exercising outdoors or leaving their home, restrictions not equally applied to the rest of the population. CO AH03 reported that:

“The pandemic made us visible ... The president by a mandatory lockdown also made an acknowledgement that we existed, , and later we had to reveal (legal action) ourselves so that they let us release from the lockdown, because it was too excessive (lockdown).” CO AH03, Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, 17).[

73]

Subsequently, many participants from Colombia perceived these age-based regulations as hostile or discriminatory, prompting legal challenges from a group of plaintiffs seeking to uphold human rights during the pandemic[Separated, Locked Down, and Unequal: The Grey Hair Revolution’s resistance to draconian quarantine in Colombia | OHRH]. In the UK, some participants appreciated the protective measures, interpreting them as a sign of being valued and cared for. However, others strongly rejected the label of vulnerability, expressing frustration at being categorised in a way that they felt diminished their autonomy and negatively affected their well-being. These findings align with Swift and Chasteen’s (2021)[

5] research, which warned against the stereotyping, homogenisation, and stigmatisation of older adults—practices that can significantly undermine well-being in later life (Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, 2023).[

6,

73]

It is understood that cultural norms and values shape human experiences, as Henrich et al. (2023)[

72] discuss in detail. As this study included two distinct cultural backgrounds the analysis identified notably differences for example, many participants in the UK found emotional support through companionship and positive sensory stimuli from pets (von Humboldt et al., 2024)[

86], while the majority of Colombian participants found stress relief through religious faith and practices (Derrer-Merk et al., 2023; see also Sisti et al., 2023)[

6,

87]. This finding highlights the interplay of individual adaptation resources and cultural differences.

The analysis in this study brought to the fore how paternalistic regulations during the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a rise in ageism, and was particularly evident at the societal level, where protective measures, often well-intentioned, reinforced stereotypes and unequal treatment. As a result, many participants reported increased experiences of discrimination, and some described feeling marginalised, especially older people who were subject to restrictive policies and public narratives (see also Ramirez et al., 2022, Sublett & Bisconti, 2020; Visintin, 2021)[

88,

89,

90]. Age-based regulations and the categorisation of older adults as physically vulnerable contributed not only to physical restrictions but also to psychosocial challenges, including increased isolation and loneliness (Yang & Gu, 2025)[

10], and overall reduced well-being (Vasara et al., 2023; Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, 2023)[

6,

73,

84]. Whether these measures were advisory or mandatory, the persistent labelling of older adults as vulnerable often led to internalised stigma, self-imposed limitations, self-induced autonomy, and adverse effects on well-being (Butler, 1969)[

91].

These findings underscore the profound influence of public policy on individuals’ self-perception, behaviour, and mental health, particularly during a health crisis. They also highlight how intersecting societal challenges—such as ageism, social exclusion, and unequal access to resources—were intensified during the pandemic, placing additional burdens on older populations (Ramirez et al., 2022)[

88]. Importantly, the study illustrates the interconnectedness of individual, community, and societal factors, as reflected in the ecological model of older adults’ well-being. This became clear at the beginning of the pandemic and continued throughout, as participants shared how they received support from family members and the community. This support included having groceries delivered, receiving more frequent courtesy calls, being driven to medical appointments, and much more.

At the societal level, participants were directly affected by age-based regulations. These measures not only fostered new forms of discrimination but also restricted access to essential resources, such as healthcare services, opportunities to maintain family relationships and reciprocal support, and the ability to experience social belonging and sustain well-being (Derrer-Merk, 2025)[

65]. The ecological framework developed in this study offers valuable insights for policymakers, emphasising the need for inclusive, supportive strategies in future health crises—strategies that respect older adults’ autonomy, promote community cohesion, and strengthen social policies to enhance well-being in later life.

Conclusions

The analysis in this study brought to the fore a substantive Ecological Theory of Older Adults’ Well-Being during the COVID-19 pandemic, developed through a qualitative synthesis of data from the C19PRC study, UK, and Colombia. This theory of older adults’ well-being during a pandemic highlights the dynamic interplay between individual, community, and societal factors in shaping their experiences. By examining the diverse and evolving challenges faced by older individuals, the study critically engages with prevailing stereotypes—particularly the narrative of older adults as inherently vulnerable—and underscores the central role of meaningful relationships and physical proximity in maintaining well-being. In doing so, it contributes to a more nuanced appreciation of well-being in later life under conditions of adversity.

The findings reveal that older adults’ experiences were deeply embedded in their family structures, social engagements, and support networks, all of which were significantly disrupted by newly introduced health protection measures. Regardless of the constraints imposed by the pandemic, the enduring need for social connection, physical touch, and a sense of belonging remained evident. Physical distancing policies, while aimed at safeguarding health, often disrupted these connections, leading to compromised well-being such as loneliness (Jain & Dhall, 2025)[

9].

Importantly, the study offers a critical lens on the broader societal impacts of health protection measures, particularly in relation to discrimination and intersectionality. The identification of ageism illustrates how overlapping forms of prejudice and stereotyping created distress for older adults during the crisis. This study challenges vulnerability and discriminatory narratives, highlighting the multifaceted nature of marginalisation (Derrer-Merk et al., 2023)[

6].

At the same time, the study documents how many older adults actively responded to rapidly changing circumstances, demonstrating notable adaptability and strength. These responses contest the narrative of vulnerability and reflect a wide range of capacities and resources (Derrer-Merk et al., 2025).[

65]

In conclusion, this research contributes to the development of an Ecological Theory of Older Adults’ Well-Being and a better understanding of the interdependence of individual, community, and societal dimensions. Additionally, this study recognises the value of both perspectives, eudemonic (e.g., setting new goals, having purpose in life) and hedonic (e.g., mixed feelings of happiness, joy, and contentment but also increased anxiety or feelings of loneliness or depression), in understanding the well-being of older adults during a health crisis. This framework offers valuable guidance for future health crisis responses, advocating for inclusive, rights-based approaches that support older adults’ autonomy, foster community cohesion, and promote social policies that enhance well-being across the lifespan.

The study also provides recommendations for policymakers and decision-makers. It calls for balanced strategies that acknowledge the psychological, social, and human rights implications of restrictive measures. By integrating an ecological perspective, future policies can more effectively address the nuanced needs of older adults and mitigate the unintended consequences of protective interventions.

Policy Recommendations for Supporting Older Adults include:

- ⮚

-

Foster Social Connectivity

Promote digital access and literacy to enable safe, meaningful interactions—such as support bubbles—within social networks. Support measures should also integrate healthcare, mental health services, and opportunities for connection.

- ⮚

-

Recognise resources and Empower Older Adults

Acknowledge older adults’ adaptive strategies across cultures. Communicate risks balanced and clearly, avoiding labels, to empower informed decision-making.

- ⮚

-

Ensure Equity Through Inclusive Engagement

Engage older adults, communities, healthcare providers, and policymakers in co-designing health-protective measures. Address discrimination and marginalisation through intersectional, community-based approaches that ensure equitable support.

- ⮚

-

Adopt an Ecological approach (see Derrer-Merk, 2025)[45]

Support well-being across physical, psychological, and social dimensions. Champion diversity and equity and apply tools like the WHO’s WICID framework to guide balanced, proportionate public health decisions.

Limitations

Despite drawing on cross-cultural data, including a wide range and large number of participants, this study has notable limitations. UK’s Participants in this study were recruited via the C19PRC online survey, inherently excluding individuals without internet access. Consequently, the lived experiences of these populations may be underrepresented. Similarly, the data from Colombia do not represent the ageing population comprehensively due to the purposeful recruitment approach (Derrer-Merk et al., 2022b, 2025)[

65,

73].

The analysis, grounded in constructivist grounded theory, maintained rigour through the thoughtful application of its principles, along with systematic reflection, ongoing discussions, and memoing. However, it is important to acknowledge that the researcher’s positionality influenced the process and is part of constructivist grounded theory approach. However, the constant comparison technique does not ensure that two analysts independently analysing the same data will arrive at identical conclusions, as it involves subjective judgment and decision-making. Additionally, findings are contextually tied to the COVID-19 pandemic, which shaped participants’ experiences. Future research should use diverse and inclusive recruitment methods to address these limitations and test the proposed ecological framework in diverse contexts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Material S1: Participants’ demographics from the UK and Colombia

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, E.D.-M. and K.M.B.; data curation, E.D.-M., M.FR.; formal analysis, E.D.-M., M.-F.R.-R. and K.M.B.; funding acquisition, R.P.B. and K.M.B.; methodology, E.D.-M., M.-F.R.-R. and K.M.B.; resources, R.P.B.; supervision, K.M.B.; writing—original draft, E.D.-M., M.-F.R.-R. and K.M.B.; review and editing, M.M-W, A.N-MCC, and K.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The initial stages of the C19PRC-research project were supported by start-up funds from the University of Sheffield (Department of Psychology, the Sheffield Methods Institute, and the Higher Education Innovation Fund via an Impact Acceleration grant administered by the university) and by the Faculty of Life and Health Sciences at Ulster University and the University of Liverpool. The research was subsequently supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) under grant number ES/V004379/1. Interviews were conducted as part of the COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) Study (

https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/psychology-consortium-covid19, accessed on 9 June 2025) and were funded by the University of Sheffield. Research undertaken in Colombia was not funded.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The UK’s ethical approval for the national representative study was granted by the University of Sheffield (ref: 033759) (approval date 17 March 2020). The qualitative sub-study was approved by the University of Liverpool (ref: 7632-7628) (approval date 31 March 2020). The Universidad El Bosque, Bogota-Colombia granted ethical approval for the data collection in Colombia (ref: 002-2021) (approval date 19 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, both verbally and in writing.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree to their data being shared publicly. Data will be stored and backed up in line with the GDPR on a university drive, and it will be available only to the research team, who will be required to sign an agreement to keep the data stored only on their university computers in password-protected files. The data can be accessed on request via Brewer, Gayle (Vice Chair, Ethics Committee), gbrewer@liverpool.ac.uk, from the University of Liverpool. The Colombian data that support the findings of this study are available from the second author, [MFR], upon reasonable request only.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants from the C19PRC and the participants from Colombia for giving a deep insight into their experience of the pandemic. Interviews were conducted as part of the C19PRC Study. The study in Colombia had support from the Universidad El Bosque, Bogota.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organisation (WHO). Opening remarks. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19 (accessed on 11 March 2020).

- Unwin, R. The 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Back to the Future? Kidney and Blood Pressure Research 2021, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health and Social Care. (DHSC). Analysis of the health, economic and social effects of COVID-19 and the approach to tiering. Cambridge, 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-health-economic-and-social-effects-of-covid-19-and-the-tiered-approach (accessed on 16 March 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ayouni, I.; Maatoug, J.; Dhouib, W.; Zammit, N.; Fredj, S.B.; Ghammam, R.; Ghannem, H. Effective public health measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19: A systematic review. BMC public health 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.T.; Hanage, W.P.; Owusu-Boaitey, N.; Cochran, K.B.; Walsh, S.P.; Meyerowitz-Katz, G. Assessing the age specificity of infection fatality rates for COVID-19: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and public policy implications. European journal of epidemiology 2020, 1123–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, H.J.; Chasteen, A.L. Ageism in the time of COVID-19. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2021, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrer-Merk, E.; Reyes-Rodriguez, M.-F.; Soulsby, L.K.; Roper, L.; Bennett, K.M. Older adults’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative systematic literature review. BMC Geriatrics 2023, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.; Malik, M.; Raees, V.; Anwar, A. Role of Mass Media and Public Health Communications in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus 2020, e10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gindodiya, A.; Deo, K.A.; Kashikar, S.; Fulzele, P.; Khatib, N. A Comparative Analysis of the Spanish Flu 1918 and COVID-19 Pandemics. The Open Public Health Journal 2021, 14, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Dhall, M. Social Isolation in COVID-19: Impact of Loneliness and NCDs on Mental and Physical Health of Older Adults. In Handbook of Aging, Health and Public Policy; Rajan, S.I., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Gu, D. Strengthening social connections to address loneliness in older adults. The Lancet Healthy Longevity 2025, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagacé, M.; Bergeron, C.D.; O’Sullivan, T.; Oostlander, S.; Dangoisse, P.; Doucet, A.; Rodrigue-Rouleau, P. The paradox of protecting the vulnerable: An analysis of the Canadian public discourse on older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pandemics, public health, and the regulation of borders, 1st ed.; Routledge, 2024; pp. 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, Viveka; Doyle, Frank; Foley, Ronan; Craven, Peter; Crowe, Noelene; Wilson, Penny. [PubMed]

- Paltasingh, T. Theories and Concepts in Gerontology: Disciplines and Discourses. In Socio-ecological determinants of older people’s mental health and well-being during COVID-19: A qualitative analysis within the Irish context. Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland; Journal contribution, 2015; pp. 19–38. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10779/rcsi.22651801.v1.

- Klausen, S.H. Understanding Older Adults’ Well-being from a Philosophical Perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies 2020, 2629–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, Simon; Lowenstein, Ariela; Hendricks, Jon; Katz, Stephen. THE NEED FOR THEORY: Critical Approaches to Social Gerontology Critical Gerontological Theory: Intellectual Fieldwork and the Nomadic Life of Ideas, 2006 2021, 15–31.

- Kim, E.S.; Tkatch, R.; Martin, D.; MacLeod, S.; Sandy, L.; Yeh, C. Resilient aging: Psychological well-being and social well-being as targets for the promotion of healthy aging. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Aging: A theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. Journal of gerontology 1956, 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Free radical theory of aging: An update: Increasing the functional life span. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2006, 1067, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R. Ageing and the brain. Postgraduate medical journal 2006, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havighurst, R.J. Social roles, work, leisure, and education. In The psychology of adult development and aging; Eisdorfer, C., Lawton, M. P., Eds.; American Psychological Association, 1973; pp. 598–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P. Environment and other determinants of well-being in older people. The Gerontologist 1983, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, H.-W.; Iwarsson, S.; Oswald, F. Aging Well and the Environment: Toward an Integrative Model and Research Agenda for the Future. The Gerontologist 2012, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, C.L.; Binney, E.A.; Culbertson, R.A. The gerontological imagination: Social influences on the development of gerontology, 1945-present. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 1992, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baars, J; Dannefer, D; Phillipson, C; Walker, A. Introduction: Critical Perspectives in Gerontology. In Aging, Globalization and Inequality: The New Critical Gerontology; Baars, J, Dannefer, D, Phillipson, C, Walker, A, Eds.; Baywood Publishing Company: New York, 2006; pp. pp 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, M; Scharf, T. Critical perspectives on ageing societies. In Critical Perspectives on Ageing Societies; Bernard, M, Scharf, T., Eds.; The Policy Press: Bristol, 2007; pp. pp 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks, J; Achenbaum, A. Historical Development of Theories of Aging. In Handbook of Theories of Aging; Bengtson, VL, Schaie, Warner, Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, 1999; pp. pp 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, P.B.; Baltes, M.M. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences.; Cambridge University Press, 1990; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L. The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2006, 1913–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N. Toward learning societies for digital aging. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.01137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano, E; Feliciano, A; Palompon, D.; Boshra, A. Aging-related Resiliency Theory Development. Belitung Nurs J. 2022, 8, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Glaser, B; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: New York, NY, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans, S. There’s more to dying than death: Qualitative research on the end-of-life. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Methods in Health Research; SAGE Publications Ltd., 2010; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forde, A.I. The American founding documents and democratic social change: A constructivist grounded theory. In Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies; 2023; p. 11940. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques; Newbury Park, CA, Sage, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory. In London: Sage, 2nd ed.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. In London, England: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty, M. The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process; SAGE Publications: London, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jarden, A.; Roache, A. What Is Well-being? International journal of environmental research and public health 2023, 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.; Lucas, R.; Smith, H. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychological Bulletin 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1989, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. The American psychologist 2000, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1995, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, I. Qualitative data analysis: A user friendly guide for social scientists; Routledge, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Derrer-Merk, Elfriede. What were older adults’ psychological and societal experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic? A qualitative approach. PhD thesis, University of Liverpool, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, O.; Butter, S.; Murphy, J.; Shevlin, M.; Hartman, T.K.; Hyland, P.; McKay, R.; Bennett, K.M.; Gibson-Miller, J.; Levita, L.; Mason, L.; Martinez, A.P.; Stocks, T.V.; Vallières, F.; Karatzias, T.; Valiente, C.; Vazquez, C.; Bentall, R.P. Context, design and conduct of the longitudinal COVID-19psychological research consortium study-wave 3. International journal of methods in psychiatric research 2021, e1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrer-Merk, E.; Reyes-Rodriguez, M.-F.; Baracaldo, P.; Guevara, M.; Rodríguez, G.; Fonseca, A.-M.; Bentall, R.P.; Bennett, K.M. Adapting in Later Life During a Health Crisis—Loro Viejo Sí Aprende a Hablar: A Grounded Theory of Older Adults’ Adaptation Processes in the UK and Colombia. Journal of Ageing and Longevity 2025, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. Symbolic interactionism. In Perspectives and methods; PrenticeHall Inc: New Jersey, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; et al. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tight, M. Saturation: An Overworked and Misunderstood Concept? Qualitative Inquiry (Original work published 2024. 2023, 30, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrer-Merk, E.; Jain, L.; Noori-Kalkhoran, O.; Taylor, R.; Drury, M.; Stain, T.; Merk, B. From fishing village to atomic town and present: A grounded theory study. PLoS ONE 2024, e0310144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Mills, J. Grounded theory: A practical guide. In SAGE, Third edition. ed.; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications Limited: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K.; Thornberg, R. The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2021, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Grounded Theory and Sensitizing Concepts. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2006, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Franco, O.H.; Laine, J.E. Accelerated ageing in the COVID-19 pandemic: A dilemma for healthy ageing. Maturitas 2022, 157, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, G.; Bennett, K.M. Resilience and caring relationships. In The social ecology of resilience; Ungar, M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, 2011; pp. 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Derrer-Merk, E.; Ferson, S.; Mannis, A.; Bentall, R.P.; Bennett, K.M. Belongingness challenged: Exploring the impact on older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze-Lutter, F.; Schimmelmann, B.G.; Schmidt, S.J. Resilience, risk, mental health and well-being: Associations and conceptual differences. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2016, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. In The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener; Diener, E., Ed.; Springer Science + Business Media, 2009; pp. 11–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.M. Social Well-Being. Social Psychology Quarterly 1998, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P.; Peterson, C. Positive clinical psychology. In A psychology of human strengths: Fundamental questions and future directions for a positive psychology; Aspinwall, L. G., Staudinger, U. M., Eds.; American Psychological Association, 2003; pp. 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrer-Merk, E.F.S.; Mannis, A.; Bentall, R.; Bennett, K.M. Older people’s family relationships in disequilibrium during the COVID-19 pandemic. What really matters? Ageing & Society 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrer-Merk, E.; Reyes-Rodriguez, M.-F.; Baracaldo, P.; Guevara, M.; Rodríguez, G.; Fonseca, A.-M.; Bentall, R.P.; Bennett, K.M. Adapting in Later Life During a Health Crisis—Loro Viejo Sí Aprende a Hablar: A Grounded Theory of Older Adults’ Adaptation Processes in the UK and Colombia. Journal of Ageing and Longevity 2025, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L. Evidence for a Life-Span Theory of Socioemotional Selectivity. Current directions in psychological science 1995, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L. Socioemotional Selectivity Theory: The Role of Perceived Endings in Human Motivation. The Gerontologist 2021, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.S.; Robbins, C.; Metzner, H.L. The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh community health study. American Journal of Epidemiology 1982, 116, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivankina, L.; Ivanova, V. Social well-being of elderly people (based on the survey results). SHS Web of Conferences 2016, 28, 01046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzuki, T.; Konta, T.; Saito, R.; Sho, R.; Osaki, T.; Souri, M.; Watanabe, M.; Ishizawa, K.; Yamashita, H.; Ueno, Y.; Kayama, T. Relationship between social support status and mortality in a community-based population: A prospective observational study (Yamagata study). BMC Public Health 2020, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilleard, C; Higgs, P. Cultures of ageing: Self, citizen and the body; Prentice Hall: Harlow, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, J.; Blasi, D.E.; Curtin, C.M.; Davis, H.E.; Hong, Z.; Kelly, D.; Kroupin, I. A Cultural Species and its Cognitive Phenotypes: Implications for Philosophy. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 2023, 349–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrer-Merk, E.; Reyes-Rodriguez, M.F.; Salazar, A.M.; Guevara, M.; Rodríguez, G.; Fonseca, A.M.; Camacho, N.; Ferson, S.; Mannis, A.; Bentall, R.P.; Bennett, K.M. Is Protecting Older Adults from COVID-19 Ageism? A Comparative Cross-cultural Constructive Grounded Theory from the United Kingdom and Colombia. The Journal of social issues 2022b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarego, M.; Tasker, F.; Costa, P. A.; Pais-Ribeiro, J.; Ferreira-Valente, A. How we survived: Older adults’ adjustment to the lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Current Psychology; 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L. There is nothing new under the sun: Ageism and intergenerational tension in the age of the COVID-19 outbreak. International Psychogeriatrics 2020, 1221–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Dalton, A.N.; Lee, J. The “Self” under COVID-19: Social role disruptions, self-authenticity and present-focused coping. PLoS ONE 2021, e0256939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, F.; Ward, E.; Khondoker, M.; Belderson, P.; Marie Minihane, A.; Dainty, J.; Hanson, S.; Holland, R.; Brown, T.; Notley, C. Health behaviour change during the UK COVID-19 lockdown: Findings from the first wave of the C-19 health behaviour and well-being daily tracker study. British journal of health psychology 2021, 624–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voinea, C.; Wangmo, T.; Vică, C. Respecting Older Adults: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 2022, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C.L.; Shmotkin, D.; Ryff, C.D. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of personality and social psychology 2002, 1007–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Tian, C.; Chen, Y.; Mao, J. The Experiences of Community-dwelling older adults during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Wuhan: A qualitative study. In Journal of Advanced Nursing; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 2021; pp. 4805–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, G.; Bennett, K.M.; MacLeod, C. The Influence of Life Experiences on the Development of Resilience in Older People With Co-morbid Health Problems [Original Research]. Frontiers in Medicine 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; McKay, G. Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In Handbook of psychology and health; Baum, A., Taylor, S.E., Singer, J. E., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, 1984; pp. 253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K.-A.; Arslan, G.; Craig, H.; Arefi, S.; Yaghoobzadeh, A.; Sharif Nia, H. The psychometric evaluation of the sense of belonging instrument (SOBI) with Iranian older adults. BMC Geriatrics 2021, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasara, P.; Simola, A.; Olakivi, A. The trouble with vulnerability. Narrating ageing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Aging Studies 2023, 64, 101106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehni, H.-J.; Wahl, H.W. Six Propositions against Ageism in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Aging & Social Policy 2020, 32, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Humboldt, S.; Silva, S.; Leal, I. How do older adults experience pet companionship? A qualitative study of the affective relationship with pets and its effect on the mental health of older adults during the Covid-19 pandemic. Educational Gerontology 2024, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisti, L.G.; Buonsenso, D.; Moscato, U.; Costanzo, G.; Malorni, W. The Role of Religions in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, L.; Monahan, C.; Palacios-Espinosa, X.; Levy, S.R. Intersections of ageism toward older adults and other isms during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of social issues 2022, 965–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sublett, J.; Bisconti, T. Benevolent Ageism’s Relationship to Self-Compassion and Meta-Memory in Older Adults. Innovation in Aging 2020, 4, 569–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, E.P. Contact with older people, ageism, and containment behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 2021, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.N. Age-Ism: Another Form of Bigotry. The Gerontologist 1969, 9, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).