Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Reproductive Physiology Across Reptilian Taxa

1.2. Dystocia and Related Reproductive Disorders

2. Integrative Scope: Hormonal Resistance, Hepatic Function, and Diagnostic Framework

3. Hormonal, Environmental, and Species-Specific Drivers

3.1. Endocrine-Metabolic Dysfunction and Reproductive Arrest

3.2. Risk Factors

3.2.1. Exogenous Factors

3.2.2. Endogenous Factors

3.3. Species-Specific Tendencies

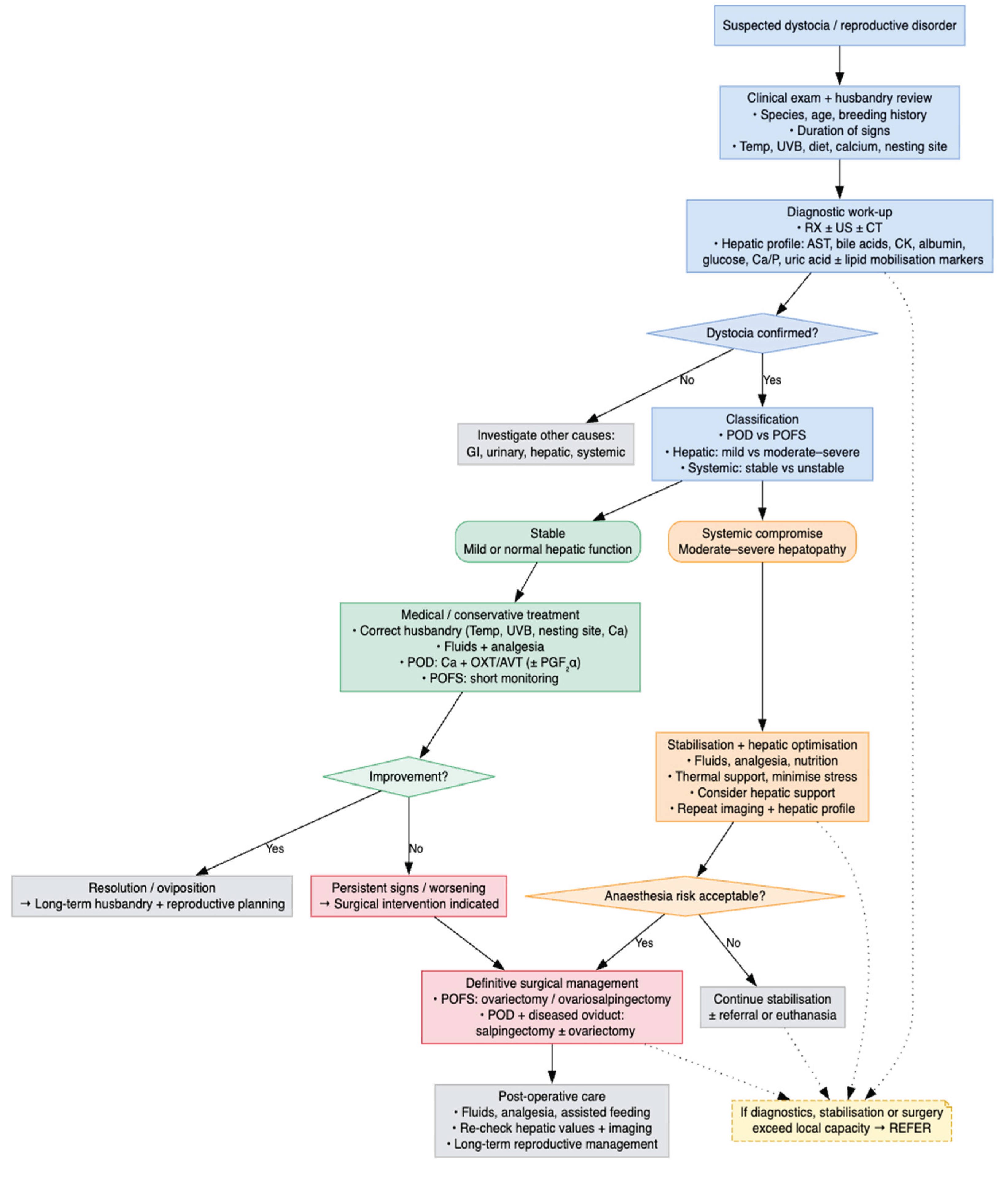

4. Diagnostic Workup

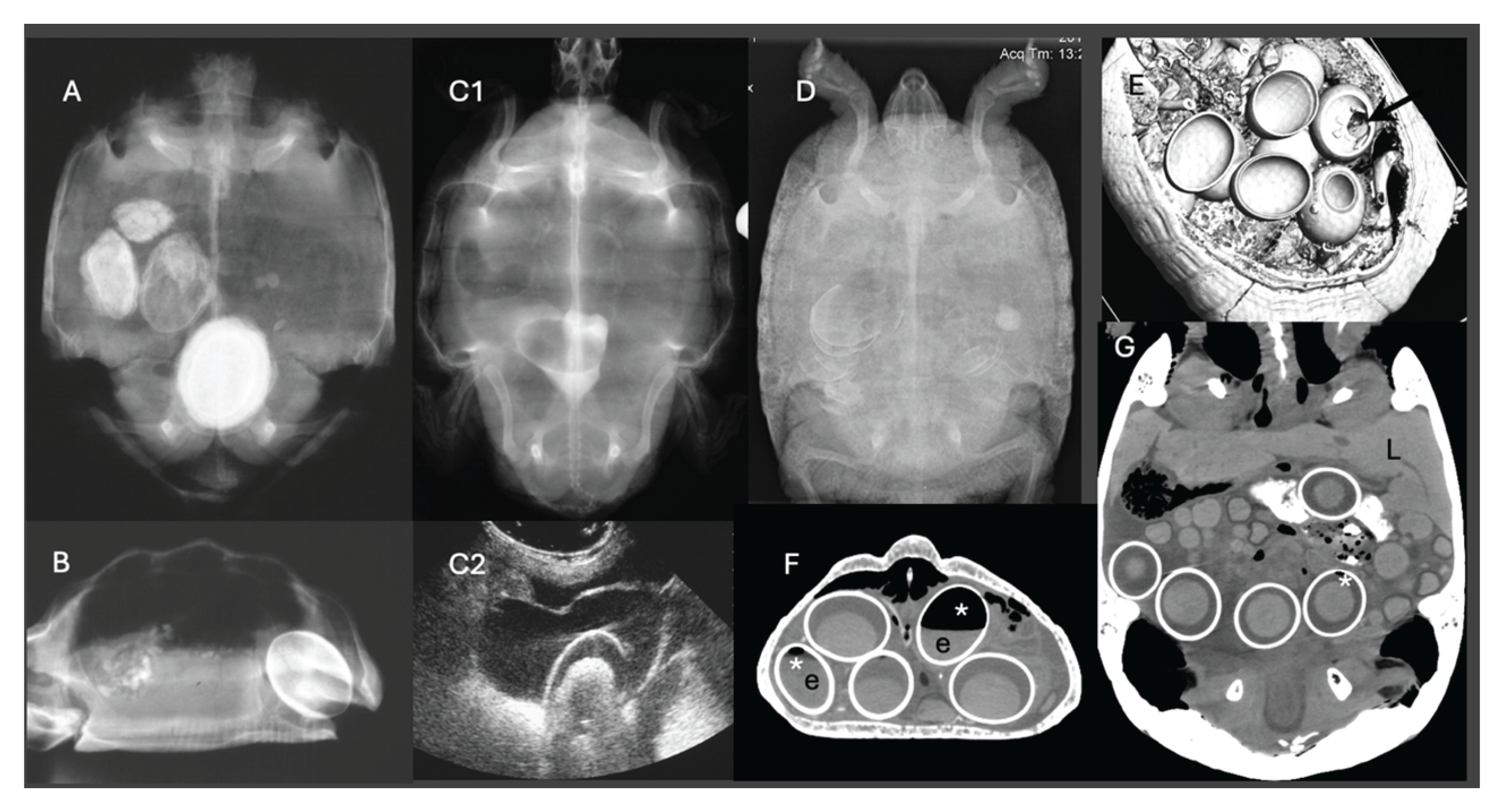

4.1. Radiographic Examination

4.2. Ultrasonography

4.3. Computed Tomography

4.4. Endoscopy

4.5. Hematology

4.6. Blood Biochemistry

5. Hormonal Treatment

5.1. General Considerations

5.2. Chelonians

5.3. Lizards

5.4. Snakes

5.5. Various

6. Surgical Intervention Thresholds

6.1. General Considerations

6.2. Considerations for Hepatic and Metabolic Derangements

7. Future Directions and Clinical Gaps

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| AVT | Arginine vasotocin |

| βHBA | Beta-hydroxybutyric acid |

| CK | Creatine phosphokinase |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| EDC | Endocrine-disrupting chemicals |

| ERα | Oestrogen receptor alpha |

| ERβ | Oestrogen receptor beta |

| ICe | Intracoelomic |

| IU | International units |

| IO | Intraosseous |

| IM | Intramuscular |

| IV | Intravenous |

| NEFA | Non-esterified fatty acids |

| PGF₂α | Prostaglandin F2 alpha |

| POFS | Pre-ovulatory follicular stasis |

| POD | Post-ovulatory dystocia |

| SC | Subcutaneous |

| UVB | Ultraviolet B radiation |

References

- Portas, T. Disorders of the Reproductive System; 2017; pp. 307–321. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J.R.; Thompson, M.B. Evolution of placentation among squamate reptiles: recent research and future directions. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2000, 127, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, D.G. Evolution of viviparity in squamate reptiles: Reversibility reconsidered. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2015, 324, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, D.G. Structure, function, and evolution of the oviducts of squamate reptiles, with special reference to viviparity and placentation. J. Exp. Zool. 1998, 282, 560–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillette, L.J., Jr.; Cree, A.; Rooney, A.A.; et al. Effects of arachidonic acid, prostaglandin F2α, prostaglandin E2, and arginine vasotocin on induction of birth in a viviparous lizard (Sceloporus jarrovi). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1992, 85, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. Hormonal Regulation of Ovarian Function in Reptiles; 2024; pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, I.Y.; DeSanti, A.; Tucker, R.K. The role of arginine vasotocin and prostaglandin F2α on oviposition and luteolysis in the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1988, 69, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNardo, D. Dystocias. In Reptile Medicine and Surgery; Mader, D.R., Ed.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1996; pp. 370–374. [Google Scholar]

- Krohmer, R.; Lutterschmidt, D. Environmental and Neuroendocrine Control of Reproduction in Snakes. In Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Snakes; 2011; Volume 9, pp. 289–346. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S.J. Reptile Obstetrics. The North American Veterinary Conference, 2006; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kummrow, M.; Cigler, P.; Mastromonaco, G. Revisiting “Preovulatory Follicular Stasis” in Reptiles. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2025, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottwitz, J.; Bohlsen, E.; Kane, L.; Sladky, K. Evaluation of the follicular cycle in ball pythons (Python regius). J. Herpetol. Med. Surg. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchzermeyer, F.; van Wyk, W. Crocodiles—Biology, husbandry and diseases. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2003, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, G.; Kirshner, D. Biology and Evolution of Crocodylians; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mader, D.; Divers, S. Current Therapy in Reptile Medicine and Surgery; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Doneley, B.; Monks, D.; Johnson, R.; Carmel, B. Reptile Medicine and Surgery in Clinical Practice; Wiley Blackwell, 2017; pp. 1–500. [Google Scholar]

- Gartrell, B.D.; Mellow, D.; McInnes, K.; Nelson, N. Folliculectomy for the treatment of pre-ovulatory follicular stasis in three illegally captured West Coast green geckos (Naultinus tuberculatus). N. Z. Vet. J. 2024, 72, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guraya, S.S. Ovarian Follicles in Reptiles and Birds. In Zoophysiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Dervas, E.; Duchesne, J.M.; van Beurden, S.J.; et al. Morphological evidence for the physiological nature of follicular atresia in veiled chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus). Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 261, 107409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuseppe, M.; Silvestre, A.M.; Luparello, M.; Faraci, L. Post-ovulatory dystocia in two small lizards: Leopard gecko (Eublepharis macularius) and crested gecko (Correlophus ciliatus). Russ. J. Herpetol. 2017, 24, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Silvestre, A. Hepatic lipidosis in reptiles. Southern Europe Veterinary Conference SEVC–AVEPA 2013, 48, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Divers, S.J.; Stahl, S.J. Mader’s Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Divers, S.; Lock, B.; Camus, M. Comparison of protein electrophoresis and biochemical analysis for the quantification of plasma albumin in healthy bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2021, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, J. Reptile Medicine and Surgery, 2nd Edition. In J. Exot. Pet Med.; Mader, D.R., Ed.; Elsevier Saunders, 2006; Volume 15, pp. 238–239. [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue, S.; McKeown, S. Nutrition of captive reptiles. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 1999, 2, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, M.E. Common reproductive pathologies in reptiles. Clin. Theriogenol. 2010, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Divers, S.J.; Cooper, J.E. Reptile hepatic lipidosis. Semin. Avian Exot. Pet Med. 2000, 9, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, T.K.; Susta, L.; Zur Linden, A.; Gardhouse, S.; Beaufrère, H. Association of plasma metabolites and diagnostic imaging findings with hepatic lipidosis in bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps) and effects of gemfibrozil therapy. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0274060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, T.; Susta, L.; Reavill, D.; Beaufrère, H. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatic lipid changes in bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Vet. Pathol. 2023, 60, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, T.; Beaufrère, H.; Reavill, D.; Susta, L. Morphological features of hepatic lipid changes in bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps), and a proposed grading system. Vet. Pathol. 2023, 60, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumpenberger, M.; Filip, T.; Grabensteiner, E.; Nowotny, N. Diagnostic imaging of various forms of dystocia in chelonians. Wien. Tierärztl. Monschr. 2001, 88, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gumpenberger, M. Veterinary computed tomography. In Veterinary Computed Tomography; Schwarz, T., Saunders, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: UK, 2011; pp. 533–544. [Google Scholar]

- Colon, V.; Gumpenberger, M. Diagnosis of hepatic lipidosis in a tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) by computed tomography. J. Exot. Pet Med. 2020, 33, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, A.; da Silva, I.C.; de Albuquerque Bonelli, M.; de Albuquerque Zanotti, L.C.; Siqueira, D.B.; Zanotti, A.P.; et al. Use of computed tomography for investigation of hepatic lipidosis in captive Chelonoidis carbonaria (Spix, 1824). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2015, 46, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumpenberger, M.; Kuebber-Heiss, A.; Richter, B. CT as a quick non-invasive imaging tool for diagnosing hepatic lipidosis in reptiles. Proceedings of WSAVA FECAVA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sosa-Higareda, M.; Beaufrère, H. Diet type, fasting duration, and computed tomography hepatic attenuation influence postprandial plasma lipids, β-hydroxybutyric acid, glucose, and uric acid in bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Am. J. Vet. Res. 2025, 86. (in press). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- X., M. A synthetic review: natural history of amniote reproductive modes in light of comparative evolutionary genomics. Biol. Rev. 2025, 100, 362–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, J.; MacKenzie, D.S.; Rostal, D.; Medler, K.; Owens, D. Estrogen induction of plasma vitellogenin in the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempi). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1997, 107, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy, B.A.; Howard, L.; Kinkaid, J.; Vidal, J.D.; Papendick, R. Yolk coelomitis in Fiji Island banded iguanas (Brachylophus fasciatus). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2008, 39, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammouche, S.B.; Remana, S.; Exbrayat, J.-M. Immunolocalization of hepatic estrogen and progesterone receptors in the female lizard Uromastyx acanthinura. C. R. Biol. 2012, 335, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, M.; Keen, J.; Campbell-Ward, M. Hypocalcemia in other species. Clinical Endocrinology of Companion Animals 2013, 335–355. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, S. Health assessment of the reptilian reproductive tract. J. Exot. Pet Med. 2008, 17, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.; Barrows, M. Yolk coelomitis in a white-throated monitor lizard (Varanus albigularis). J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2010, 81, 121–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubian, E.; Palotti, G.; Di Ianni, F.; Vetere, A. Disorders of the female reproductive tract in chelonians: A review. Animals 2025, 15, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedley, J. Reproductive diseases of reptiles. In Pract. 2016, 38, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, D.A.; Leeson, S. Metabolic bone disease in lizards: Prevalence and potential for monitoring bone health. In Metabolic Bone Disease in Lizards; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, J.M. Updates and practical approaches to reproductive disorders in reptiles. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2010, 13, 349–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerreta, A.J.; McEntire, M.S. Hypothalamic and pituitary physiology in birds and reptiles. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2025, 28, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigler, P.; Dervas, E.; Richter, H.; Hatt, J.-M.; Kummrow, M. Ultrasonographic and computed tomographic characteristics of the reproductive cycle in female veiled chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2023, 54, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendić, M.; Samardžija, M.; Prvanović Babić, N.; Bacić, G.; Karadjole, T.; Lojkić, M.; et al. Postovulatory egg retention (dystocia) in lizards—Diagnostic and therapeutic options. Kleintierpraxis 2017, 62, 754–764. [Google Scholar]

- Work, T.M.; Balazs, G.H. Pathology and distribution of sea turtles landed as bycatch in the Hawaii-based North Pacific pelagic longline fishery. J. Wildl. Dis. 2010, 46(2), 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Girolamo, N.; Selleri, P. Reproductive disorders in snakes. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2017, 20(2), 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.; Currylow, A.; Ridgley, F. Egg retention in wild-caught Python bivittatus in the Greater Everglades Ecosystem, Florida, USA. Herpetol. J. 2022, 32, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.J.; Davies, D. Case report—dystocia in an African rock python. Br. Herpetol. Soc. Bull. 1993, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A.J.; Lewbart, G.A. Treatment of dystocia in a leopard gecko (Eublepharis macularius) by percutaneous ovocentesis. Vet. Rec. 2006, 158(21), 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efendić, M.; Samardžija, M.; Capak, H.; Bacić, G.; Žura Žaja, I.; Magaš, V.; et al. Induction of oviposition in bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps) with postovulatory egg retention (dystocia)—a case report. Vet. Arhiv. 2019, 89, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummrow, M.S.; Mastromonaco, G.F.; Crawshaw, G.; Smith, D.A. Fecal hormone patterns during non-ovulatory reproductive cycles in female veiled chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 168(3), 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimm, R.H.; Dutton, C.J.; O’Handley, S.; Mastromonaco, G.F. Assessment of the reproductive status of female veiled chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus) using hormonal, behavioural and physical traits. Zoo Biol. 2015, 34(1), 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiri, B.S.; Soroori, S.; Rostami, A.; Molazem, M.; Bahonar, A. Ultrasonography and CT examination of ovarian follicular development in Testudo graeca during 1 year in captivity. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9(6), 2606–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumpenberger, M. Diagnostic imaging of reproductive tract disorders in reptiles. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2017, 20(2), 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alworth, L.C.; Hernandez, S.M.; Divers, S.J. Laboratory reptile surgery: principles and techniques. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2011, 50(1), 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, E.; Garner, M. Infectious Diseases and Pathology of Reptiles: Color Atlas and Text, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Innis, C.J.; Boyer, T.H. Chelonian reproductive disorders. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2002, 5(3), 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, M.; Sandfoss, M.R.; Reichling, S.B.; Richter, M.M.; Cantrell, J.R.; Knotek, Z.; et al. Ultrasound description of follicular development in the Louisiana pinesnake (Pituophis ruthveni). Animals 2022, 12(21), 2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, R.S. Lizard reproductive medicine and surgery. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2002, 5(3), 579–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D.; Ed, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Reptile reproductive problems. In Proceedings of the WSAVA World Congress, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanová, D.; Halán, M. The use of ultrasonography in diagnostic imaging of reptiles. Folia Vet. 2016, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetere, A.; Bigliardi, E.; Masi, M.; Rizzi, M.; Leandrin, E.; Di Ianni, F. Egg removal via cloacoscopy in three dystocic leopard geckos (Eublepharis macularius). Animals 2023, 13(5), 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innis, C.J.; Hernandez-Divers, S.; Martinez-Jimenez, D. Coelioscopic-assisted prefemoral oophorectomy in chelonians. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2007, 230(7), 1049–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, S.; Sanchez-Migallon Guzman, D.; Kass, P.H.; Giuffrida, M.A.; Mayhew, P.D. Evaluation of ventral and left lateral approaches to coelioscopy in bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). Am. J. Vet. Res. 2020, 81(3), 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, E.; Antolini, G.; Lubian, E.; Bronzo, V.; Romussi, S. Comparison of lateral and dorsal recumbency during endoscope-assisted oophorectomy in mature pond sliders (Trachemys scripta). Animals 2020, 10(9), 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mans, C.; Foster, J.D. Endoscopy-guided ectopic egg removal from the urinary bladder in a leopard tortoise (Stigmochelys pardalis). Can. Vet. J. 2014, 55(6), 569–572. [Google Scholar]

- Di Girolamo, N.; Selleri, P. Clinical applications of cystoscopy in chelonians. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2015, 18(3), 507–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.W. Clinical pathology of reptiles. In Reptile Medicine and Surgery; Mader, D.R., Ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2006; pp. 453–470. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado, M.; Díaz-Paniagua, C.; Quevedo, M.A.; Aguilar, J.M.; Prescott, I.M. Hematology and clinical chemistry in dystocic and healthy post-reproductive female chameleons. J. Wildl. Dis. 2002, 38(2), 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessauer, H.C. Blood chemistry of reptiles: physiology and evolutionary aspects. In Biology of the Reptilia; Gans, C., Parsons, T.S., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1970; Volume 3, pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dutra, G.H. Diagnostic value of hepatic enzymes, triglycerides and serum proteins for detecting hepatic lipidosis in Chelonoidis carbonaria in captivity. J. Life Sci. 2014, 8, 633–639. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, T.W. Exotic Animal Hematology and Cytology, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Ames, IA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Knotek, Z.; Knotková, Z.; Čermáková, E.; Dorrestein, G.M.; Heckers, K.O.; Komenda, D. Plasma bile acids in healthy green iguanas and iguanas with chronic liver diseases. Vet. Med. (Praha) 2023, 68(9), 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul-M. Gibbons, Ed. Reptile and amphibian urinary tract medicine: diagnosis and therapy. In Proceedings of the Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians, 2007.

- Anthonioz, C.; Abadie, Y.; Reversat, E.; Lafargue, A.; Delalande, M.; Renaudineau, T.; et al. Heterogenous within-herd seroprevalence against epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus type 8 (EHDV-8) after massive virus circulation in cattle in France, 2023. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1562883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacumio, L.P.T.; Tarbert, D.K.; Keel, K.; Ammersbach, M.; Beaufrère, H. Assessment of β-hydroxybutyric acid (BHBA) as a plasma biomarker for hepatic lipidosis in bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). UC Davis STAR Program Poster, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pacumio, L.; Tarbert, D.; Ammersbach, M.; Beaufrère, H. Method comparison and reference intervals of β-hydroxybutyric acid measurements using a veterinary point-of-care ketone meter and a reference laboratory analyzer in central bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). J. Herpetol. Med. Surg. 2025, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.F. A comparison of activities of metabolic enzymes in lizards and rats. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 1972, 42(4), 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, L. Comparison of liver cytology and biopsy diagnoses in dogs and cats: 56 cases. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2001, 30(1), 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmquist, D.L.; Jenkins, T.C. Fat in lactation rations: review. J. Dairy Sci. 1980, 63(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Music, M.K.; Strunk, A. Reptile critical care and common emergencies. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2016, 19(2), 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.K.; Thomas, D.L.; Rose, J. Oxytocin dosage in turtles. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2007, 6(2), 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.L. Some options to induce oviposition in turtles. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2007, 6(2), 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailey, A.; Loumbourdis, N. Population ecology and conservation of tortoises: demographic aspects of reproduction in Testudo hermanni. Herpetol. J. 1990, 1, 425–434. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S.J.; Ed. Managing dystocia in snakes. In ExoticsCon; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, J.W.; Marion, C.J. Exotic Animal Formulary, 5th ed.; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Govendan, P.N.; Kurniawan, L.; Raharjo, S. Non-invasive treatment in a case of post-ovulatory egg stasis in a Burmese python (Python bivittatus). 2019. pISSN : 2301-7848; eISSN : 2477-6637.

- Millichamp, N.; Lawrence, K.; Jacobson, E.; Jackson, O.; Bell, D. Egg retention in snakes. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1984, 183, 1213–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillette, L.J.; Masson, G.R.; DeMarco, V. Effects of prostaglandin F2α, prostaglandin E2, and arachidonic acid on induction of oviposition in oviparous lizards. Prostaglandins 1991, 42(6), 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacy, N.I.; Alleman, A.R.; Sayler, K.A. Diagnostic hematology of reptiles. Clin. Lab. Med. 2011, 31(1), 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bel, L.; Mihalca, A.; Peștean, C.; Ober, C.; Oana, L. Surgical management of dystocia in snakes and lizards. Bull. Univ. Agric. Sci. Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca Vet. Med. 2015, 72(1), 205–206. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, R.W.; Smith, A. Surgical intervention to relieve dystocia in a python. Vet. Rec. 1979, 104(24), 551–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knotek, Z.; Čermáková, E.; Oliveri, M. Reproductive medicine in lizards. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2017, 20(2), 411–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knotek, Z.; Musilová, A.; Knotková, Z.; Trnková, Š.; Babák, V. Alfaxalone anaesthesia in the green iguana (Iguana iguana). Acta Vet. Brno 2013, 82, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, H.; Godke, A.M.; Aguilar, M.G.; Mitchell, M.A. Evaluating the physiologic effects of alfaxalone, dexmedetomidine, and midazolam in common blue-tongued skinks (Tiliqua scincoides). Animals 2024, 14(18), 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, P.; Whiteside, D.; Lewington, J.; Solorza, L.M. Clinical Anatomy and Physiology of Exotic Species: Structure and Function of Mammals, Birds, Reptiles and Amphibians; Elsevier, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Larouche, C.B.; Johnson, R.; Beaudry, F.; Mosley, C.; Gu, Y.; Zaman, K.A.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of midazolam and its major metabolite 1-hydroxymidazolam in the ball python (Python regius). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 42(6), 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Divers, S.M.; Schumacher, J.; Stahl, S.; Hernandez-Divers, S.J. Comparison of isoflurane and sevoflurane anesthesia after premedication with butorphanol in the green iguana (Iguana iguana). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2005, 36(2), 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley, C.A.; Dyson, D.; Smith, D.A. Cardiovascular dose-response effects of isoflurane alone and with butorphanol in the green iguana (Iguana iguana). Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2004, 31(1), 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, L.L.; Jenne, K.J.; Diggs, H.E. Medetomidine–ketamine anesthesia in red-eared slider turtles (Trachemys scripta elegans). Contemp. Top. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2001, 40(3), 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Delaney, C.A.; Ed. Use of nutraceuticals to manage liver disease in bearded dragons (Pogona vitticeps). In Proceedings of the ARAV Conference, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lance, V. Reptile reproduction and endocrinology; 2002; pp. 338–358. [Google Scholar]

- Guillette, L.J., Jr.; Gross, T.S.; Masson, G.R.; Matter, J.M.; Percival, H.F.; Woodward, A.R. Developmental abnormalities of the gonad and altered sex hormone concentrations in juvenile alligators from contaminated lakes in Florida. Environ. Health Perspect. 1994, 102(8), 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlatt, V.L.; Bayen, S.; Castaneda-Cortés, D.; Delbès, G.; Grigorova, P.; Langlois, V.S.; et al. Impacts of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on reproduction in wildlife and humans. Environ. Res. 2022, 208, 112584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, I.; Codoñer, F.M.; Vilella, F.; Valbuena, D.; Martinez-Blanch, J.F.; Jimenez-Almazán, J.; et al. Evidence that the endometrial microbiota has an effect on implantation success or failure. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215(6), 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omu, A.E.; Al-Azemi, M.K.; Al-Maghrebi, M.; Mathew, C.T.; Omu, F.E.; Kehinde, E.O.; et al. Molecular basis for the effects of zinc deficiency on spermatogenesis: an experimental study in Sprague–Dawley rats. Indian J. Urol. 2015, 31(1), 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chelonian species | Common name | Type of dystocia | Key risk factors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testudo graeca | Greek tortoise | POD due to pelvic obstruction | Narrow pelvis, lack of nesting site, dehydration | [10,44] |

| Testudo hermanni | Hermann’s tortoise | POFS and coelomitis | Persistent follicular development, inflammation, hypocalcaemia | [44,50] |

| Trachemys scripta elegans | Red-eared slider | Cloacal prolapse and egg impaction | Water quality issues, inadequate UVB radiation, cloacal muscle weakness | [44,45,49] |

| Chelonia mydas | Green sea turtle | Exhaustion-related egg retention during nesting | Long oviposition, dehydration, human disturbance | [44,51] |

| Snake Species | Common Name | Type of Dystocia / Reproductive Issue | Key Risk Factors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Python regius | Ball python | Follicular stasis, retained unfertilized ova, coelomitis | Prolonged follicular phase, improper pairing, low temperature | [10,52] |

| Python molurus bivittatus | Burmese python | Obstructive dystocia, egg retention | Obesity, large clutch size, low calcium, oviposition failure | [53] |

| Python sebae | African rock python | Egg-binding with cloacal prolapse | Egg retention, lack of appropriate nesting, dehydration | [54] |

| Lampropeltis getula | Common kingsnake | POD | Inadequate humidity, inappropriate nesting environment | [45] |

| Lizard Species | Common Name | Type of Dystocia / Reproductive Issue | Key Risk Factors | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eublepharis macularius | Leopard gecko | POD | Lack of UVB radiation, calcium deficiency, | [20,55] |

| Correlophus ciliatus | Crested gecko | POD | Poor husbandry, lack of nesting substrate | [20] |

| Pogona vitticeps | Bearded dragon | POD with large clutch | Hypocalcaemia, dehydration, improper thermal and UVB gradients | [56] |

| Chamaeleo calyptratus | Veiled chameleon | POFS | Calcium deficiency, chronic reproductive cycling, photoperiod issues | [57,58] |

| Varanus albigularis | White-throated monitor | Yolk coelomitis from retained follicles | Failure to oviposit, prolonged retention | [43] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).