Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Microneedle (MN) technologies have emerged as a groundbreaking platform for transdermal and intradermal drug delivery, offering a minimally invasive alternative to oral and parenteral routes. Unlike passive transdermal systems, MNs allow the permeation of hydrophilic macromolecules, such as peptides, proteins, and vaccines, by penetrating the stratum corneum barrier without causing pain or tissue damage, unlike hypodermic needles. Recent advances in materials science, microfabrication, and biomedical engineering have enabled the development of various MN types, including solid, coated, dissolving, hollow, hydrogel-forming, and hybrid designs. Each type has unique mechanisms, fabrication techniques, and pharmacokinetic profiles, providing customized solutions for a range of therapeutic applications. The integration of 3D printing technologies and stimulus-responsive polymers into microneedle systems has opened the door for patches that pair drug delivery with real-time physiological sensing. Over the years, microneedle applications have grown beyond vaccines to include the delivery of insulin, anticancer agents, contraceptives, and various cosmeceutical ingredients, highlighting the versatility of this platform. Despite this progress, broader clinical and commercial adoption is still limited by issues such as scalable and reliable manufacturing, patient acceptance, and meeting regulatory expectations. Overcoming these barriers will require coordinated efforts across engineering, clinical research, and regulatory science. This review thoroughly summarizes MN technologies, beginning with their classification and drug-delivery mechanisms, and then explores innovations, therapeutic uses, and translational challenges. It concludes with a critical analysis of clinical case studies and a future outlook for global healthcare. By comparing technological progress with regulatory and commercial hurdles, this article highlights the opportunities and limitations of MN systems as a next-generation drug-delivery platform.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. History of MN

1.2. Structure and Design Principles

2. Classification of Microneedles

2.1. Solid Microneedles

2.2. Coated Microneedles

2.3. Dissolving Microneedles

2.4. Hollow Microneedles

2.5. Hydrogel-Forming Microneedles

2.6. Hybrid and Next-Generation Microneedles

3. Mechanisms of Drug Delivery via Microneedles

3.1. Passive Diffusion via Solid Microneedles

3.2. Coating Dissolution Kinetics in Coated Microneedles

3.3. Biodegradable Matrix Dissolution in Dissolving Microneedles

3.4. Infusion Through Hollow Microneedles

3.5. Swelling and Sustained Release via Hydrogel-Forming Microneedles

3.6. Hybrid and Stimuli-Responsive Mechanisms

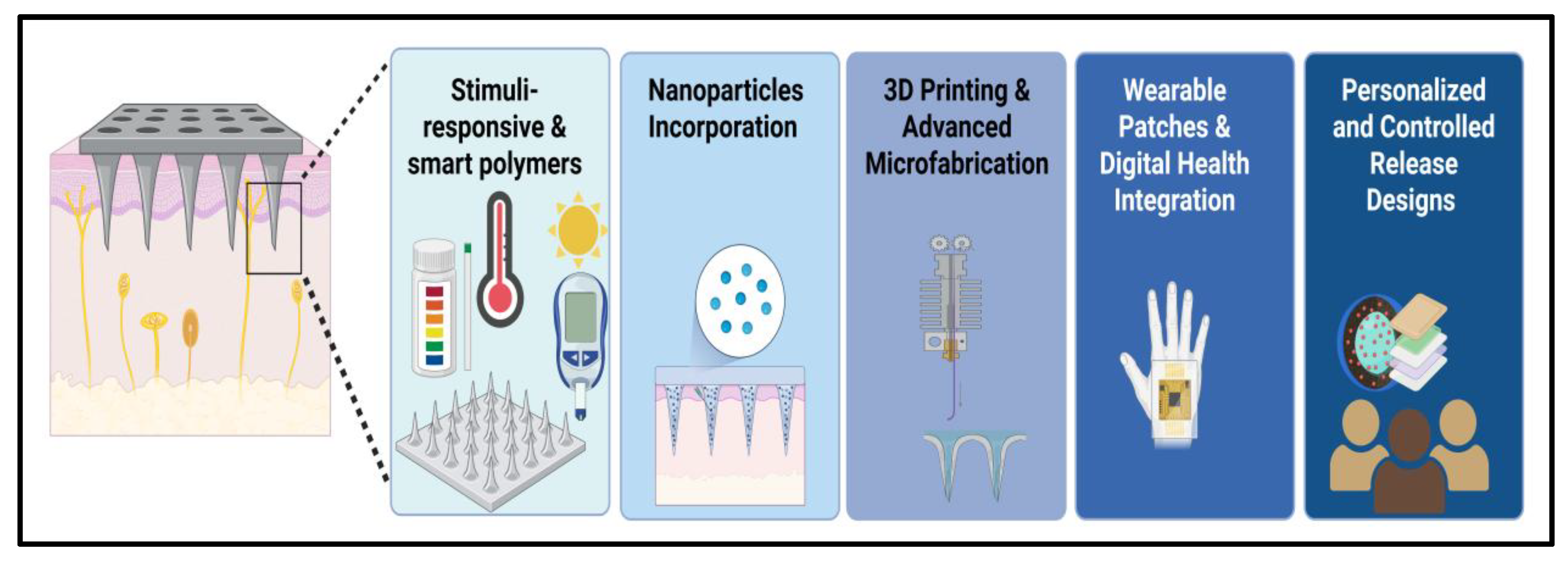

4. Innovations in Microneedle Technologies

4.1. Stimuli-Responsive and Smart Polymers

4.2. Nanoparticle Incorporation and Multifunctional Microneedles

4.3. D Printing and Advanced Microfabrication

4.4. Wearable Patches and Digital Health Integration

4.5. Personalized and Controlled Release Designs

4.6. Advances in Smart Microneedle Design: 4D Printing and AI Optimization

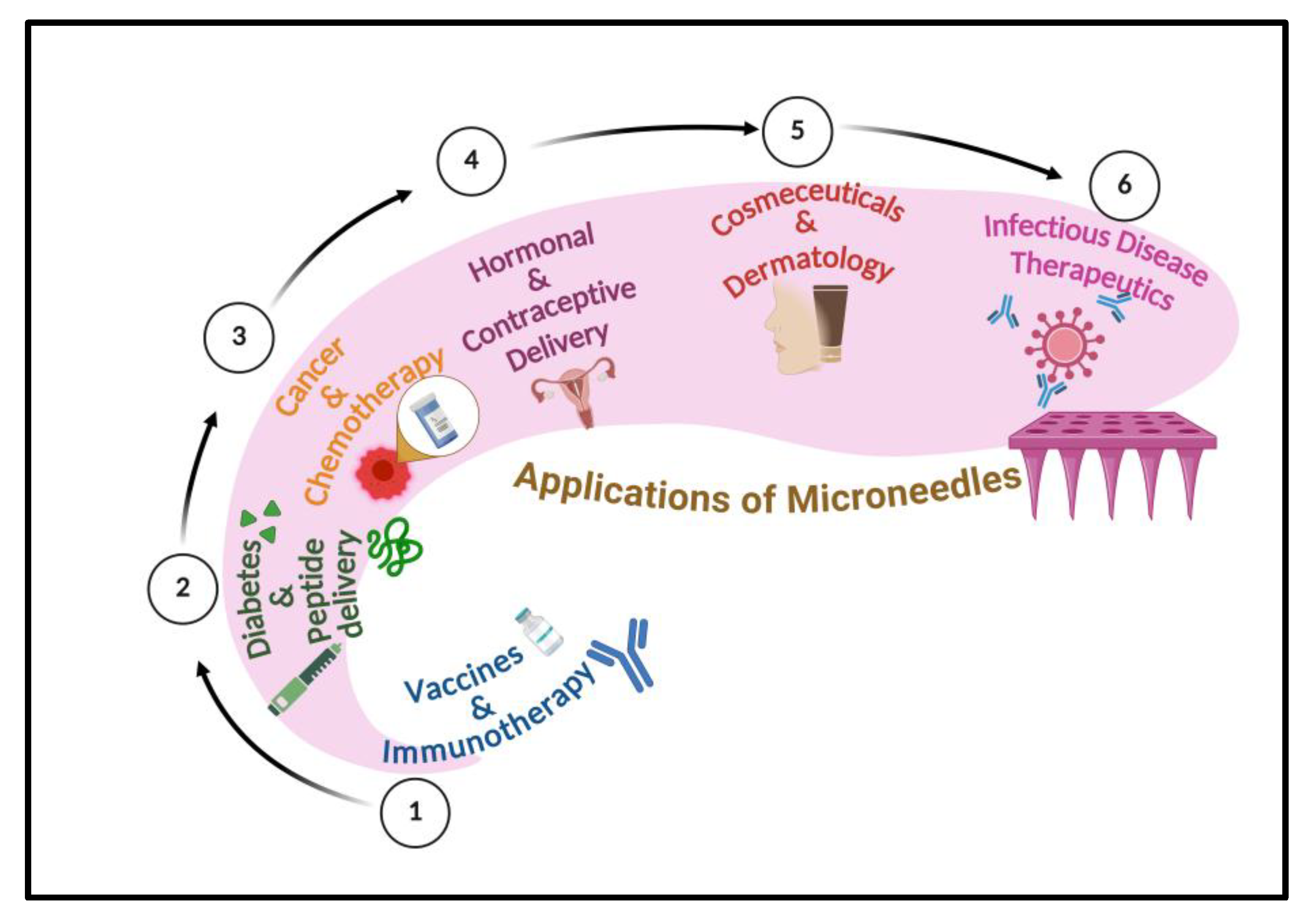

5. Therapeutic Applications of Microneedles

5.1. Vaccines and Immunotherapy

5.2. Diabetes and Peptide Delivery

5.3. Cancer Therapy and Chemotherapy

5.4. Hormonal and Contraceptive Delivery

5.5. Cosmeceuticals and Dermatology

5.6. Infectious Disease Therapeutics

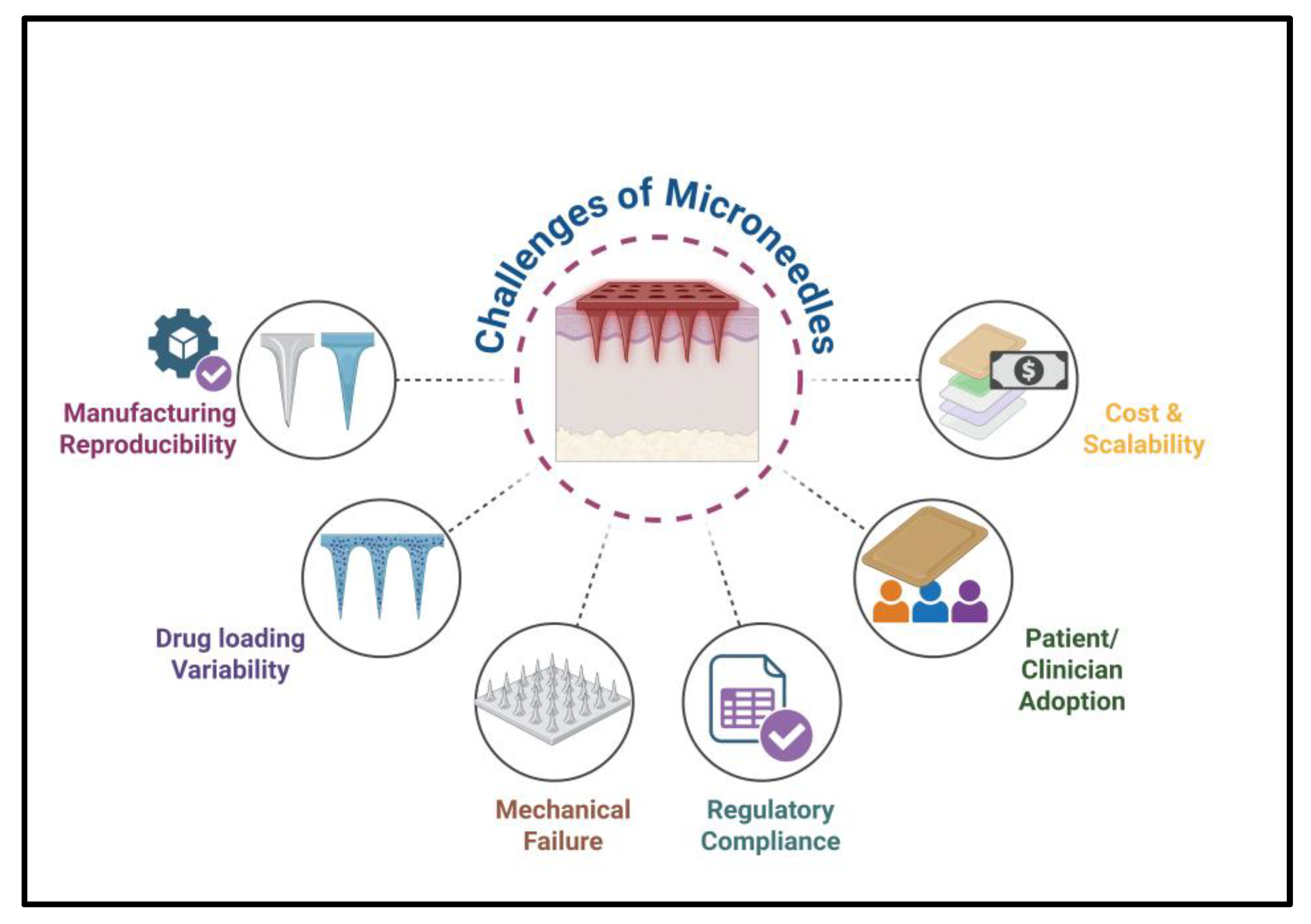

6. Commercial Challenges, Regulatory Pathways, and Case Studies

6.1. Manufacturing and Scalability Challenges

6.2. Safety and Clinical Validation

6.3. Regulatory Approval Pathways

6.4. Market Adoption and User Acceptance

6.5. Case Studies of Marketed and Trial-Stage MN Products

7. Future Perspectives

8. Conclusion

References

- Jung, J.H.; Jin, S.G. Microneedle for transdermal drug delivery: current trends and fabrication. J Pharm Investig 2021, 51, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Sun, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Meng, D. Advances in clinical applications of microneedle. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1607210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulimane Shivaswamy, R.; Binulal, P.; Benoy, A.; Lakshmiramanan, K.; Bhaskar, N.; Pandya, H.J. Microneedles as a Promising Technology for Disease Monitoring and Drug Delivery: A Review. ACS Mater Au 2025, 5, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldawood, F.K.; Andar, A.; Desai, S. A Comprehensive Review of Microneedles: Types, Materials, Processes, Characterizations and Applications. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, D.; Damiri, F.; Rojekar, S.; Zehravi, M.; Ramproshad, S.; Dhoke, D.; Musale, S.; Mulani, A.A.; Modak, P.; Paradhi, R.; et al. Recent Advancements in Microneedle Technology for Multifaceted Biomedical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitore, J.G.; Pagar, S.; Singh, N.; Karunakaran, B.; Salve, S.; Hatvate, N.; Rojekar, S.; Benival, D. A comprehensive review of nanosuspension loaded microneedles: fabrication methods, applications, and recent developments. J. Pharm. Investig. 2023, 53, 475–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Azizi Machekposhti, S.; Narayan, R.J. Evolution of Transdermal Drug Delivery Devices and Novel Microneedle Technologies: A Historical Perspective and Review. JID Innov 2023, 3, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.; Ma, S.; Zhao, P.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y. Microneedles at the Forefront of Next Generation Theranostics. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12, e2412140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yu, Q.; Huang, C.; Li, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, D. Microneedles as transdermal drug delivery system for enhancing skin disease treatment. Acta Pharm Sin B 2024, 14, 5161–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gu, Q.; Sui, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhou, R. Design and optimization of hollow microneedle spacing for three materials using finite element methods. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Dong, Z.; Xu, X.; Bei, H.P.; Yuen, H.Y.; James Cheung, C.W.; Wong, M.S.; He, Y.; Zhao, X. Going below and beyond the surface: Microneedle structure, materials, drugs, fabrication, and applications for wound healing and tissue regeneration. Bioact Mater 2023, 27, 303–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuan-Mahmood, T.M.; McCrudden, M.T.; Torrisi, B.M.; McAlister, E.; Garland, M.J.; Singh, T.R.; Donnelly, R.F. Microneedles for intradermal and transdermal drug delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci 2013, 50, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shriky, B.; Babenko, M.; Whiteside, B.R. Dissolving and Swelling Hydrogel-Based Microneedles: An Overview of Their Materials, Fabrication, Characterization Methods, and Challenges. Gels 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojekar, S.; Parit, S.; Gholap, A.D.; Manchare, A.; Nangare, S.N.; Hatvate, N.; Sugandhi, V.V.; Paudel, K.R.; Ingle, R.G. Revolutionizing Eye Care: Exploring the Potential of Microneedle Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waghule, T.; Singhvi, G.; Dubey, S.K.; Pandey, M.M.; Gupta, G.; Singh, M.; Dua, K. Microneedles: A smart approach and increasing potential for transdermal drug delivery system. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 109, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Gill, H.S.; Andrews, S.N.; Prausnitz, M.R. Kinetics of skin resealing after insertion of microneedles in human subjects. J Control Release 2011, 154, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, O.; Blayney, G.J.; Gualeni, B.; Birchall, J.C.; Eng, P.F.; Ashraf, H.; Sharma, S.; Guy, O.J. Design, fabrication, and characterisation of a silicon microneedle array for transdermal therapeutic delivery using a single step wet etch process. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2022, 171, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yang, L.; Cui, Y. Microneedles: materials, fabrication, and biomedical applications. Biomed Microdevices 2023, 25, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, M.; Johnson, B.; Ameri, M.; Nyam, K.; Libiran, L.; Zhang, D.D.; Daddona, P. Transdermal delivery of desmopressin using a coated microneedle array patch system. J Control Release 2004, 97, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Park, J.H.; Prausnitz, M.R. Microneedles for drug and vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2012, 64, 1547–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji Rad, Z.; Prewett, P.D.; Davies, G.J. An overview of microneedle applications, materials, and fabrication methods. Beilstein J Nanotechnol 2021, 12, 1034–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.; Wu, C. Microneedle, bio-microneedle and bio-inspired microneedle: A review. J Control Release 2017, 251, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, R.F.; Raj Singh, T.R.; Woolfson, A.D. Microneedle-based drug delivery systems: microfabrication, drug delivery, and safety. Drug Deliv 2010, 17, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, D.; Miyatsuji, M.; Sakoda, H.; Yamamoto, E.; Miyazaki, T.; Koide, T.; Sato, Y.; Izutsu, K.I. Mechanical Characterization of Dissolving Microneedles: Factors Affecting Physical Strength of Needles. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, H.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, F.; Xia, W.; Chen, L.; Li, M.; Yang, T.; Qiao, Y.; et al. From mechanism to applications: Advanced microneedles for clinical medicine. Bioact Mater 2025, 51, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi, M.; Akbari, M. 3D printed hollow microneedles: the latest innovation in drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2025, 22, 1487–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohite, P.; Puri, A.; Munde, S.; Ade, N.; Kumar, A.; Jantrawut, P.; Singh, S.; Chittasupho, C. Hydrogel-Forming Microneedles in the Management of Dermal Disorders Through a Non-Invasive Process: A Review. Gels 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, F.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Bei, J.; Lei, L.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, C. Designing Multifunctional Microneedles in Biomedical Engineering: Materials, Methods, and Applications. Int J Nanomedicine 2025, 20, 8693–8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikci, S.; van den Bergh, N.; Boehm, H. Kinetic and Mechanistic Release Studies on Hyaluronan Hydrogels for Their Potential Use as a pH-Responsive Drug Delivery Device. Gels 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, J.; Ye, D.; Chen, R.; Fan, Q.; Liao, Q. Microneedle-Based Biofuel Cell with MXene/CNT Hybrid Bioanode: Fundamental and Biomedical Application. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, e16229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, B.; Maity, S.; Jain, A.; Banerjee, S. Next-generation stimuli-responsive polymers for a sustainable tomorrow. Chem Commun (Camb) 2025, 61, 12265–12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, N.H.; Chien, T.B.; Cuong, D.X. Polymer-Based Hydrogels Applied in Drug Delivery: An Overview. Gels 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.D.R.; Putra, K.B.; Chen, L.; Montgomery, J.S.; Shih, A. Mosquito proboscis-inspired needle insertion to reduce tissue deformation and organ displacement. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedir, T.; Kadian, S.; Shukla, S.; Gunduz, O.; Narayan, R. Additive manufacturing of microneedles for sensing and drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2024, 21, 1053–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ita, K. Dissolving microneedles for transdermal drug delivery: Advances and challenges. Biomed Pharmacother 2017, 93, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Jeong, J.; Jo, J.K.; So, H. Hollow microneedles as a flexible dosing control solution for transdermal drug delivery. Mater Today Bio 2025, 32, 101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroche, A.F.; Nissan, H.E.; Daniele, M.A. Hydrogel-Forming Microneedles and Applications in Interstitial Fluid Diagnostic Devices. Adv Healthc Mater 2025, 14, e2401782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Vora, L.K.; Dominguez-Robles, J.; Naser, Y.A.; Li, M.; Larraneta, E.; Donnelly, R.F. Hydrogel-forming microneedles for rapid and efficient skin deposition of controlled release tip-implants. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2021, 127, 112226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Huai, S.; Wei, H.; Xu, Y.; Lei, L.; Chen, H.; Li, X.; Ma, H. Dissolvable hybrid microneedle patch for efficient delivery of curcumin to reduce intraocular inflammation. Int. J. Pharm 2023, 643, 123205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, M.; Fu, J.; Sun, Y.; Lu, C.; Quan, G.; Pan, X.; Wu, C. Recent advances in microneedles-mediated transdermal delivery of protein and peptide drugs. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021, 11, 2326–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Saeed Al-Japairai, K.; Mahmood, S.; Hamed Almurisi, S.; Reddy Venugopal, J.; Rebhi Hilles, A.; Azmana, M.; Raman, S. Current trends in polymer microneedle for transdermal drug delivery. Int J Pharm 2020, 587, 119673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, Y.; Mei, R.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, L. Revealing drug release and diffusion behavior in skin interstitial fluid by surface-enhanced Raman scattering microneedles. J Mater Chem B 2023, 11, 3097–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiri, F.; Kommineni, N.; Ebhodaghe, S.O.; Bulusu, R.; Jyothi, V.; Sayed, A.A.; Awaji, A.A.; Germoush, M.O.; Al-Malky, H.S.; Nasrullah, M.Z.; et al. Microneedle-Based Natural Polysaccharide for Drug Delivery Systems (DDS): Progress and Challenges. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.A.; Xu, S.; Shi, X.; Jin, Y.; Pan, Z.; Hao, T.; Li, G.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Bioengineered microneedles and nanomedicine as therapeutic platform for tissue regeneration. J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toews, P.; Bates, J. Influence of drug and polymer molecular weight on release kinetics from HEMA and HPMA hydrogels. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 16685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moawad, F.; Pouliot, R.; Brambilla, D. Dissolving microneedles in transdermal drug delivery: A critical analysis of limitations and translation challenges. J Control Release 2025, 383, 113794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.C.; Ahmadinejad, E.; Tasoglu, S. Optimizing Solid Microneedle Design: A Comprehensive ML-Augmented DOE Approach. ACS Meas Sci Au 2024, 4, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.F.; Singh, T.R.; Garland, M.J.; Migalska, K.; Majithiya, R.; McCrudden, C.M.; Kole, P.L.; Mahmood, T.M.; McCarthy, H.O.; Woolfson, A.D. Hydrogel-Forming Microneedle Arrays for Enhanced Transdermal Drug Delivery. Adv Funct Mater 2012, 22, 4879–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Xian, H.; Xia, C.; Liu, Y.; Du, S.; Wang, B.; Xue, P.; Wang, B.; Kang, Y. Polymer homologue-mediated formation of hydrogel microneedles for controllable transdermal drug delivery. Int J Pharm 2024, 666, 124768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.G.; White, L.R.; Estrela, P.; Leese, H.S. Hydrogel-Forming Microneedles: Current Advancements and Future Trends. Macromol Biosci 2021, 21, e2000307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Dey Chowdhury, S. Multifunctional Hydrogel Microneedles (HMNs) in Drug Delivery and Diagnostics. Gels 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, J.; Minko, T. Multifunctional and stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for targeted therapeutic delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2021, 18, 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Pandey, S.; Shiekmydeen, J.; Kumar, M.; Chopra, S.; Bhatia, A. Therapeutic Potential of Microneedle Assisted Drug Delivery for Wound Healing: Current State of the Art, Challenges, and Future Perspective. AAPS PharmSciTech 2025, 26, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, P.; Mohanty, T.; Mohapatra, R. Advancements in Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems: Harnessing the Potential of Macromolecular Assisted Permeation Enhancement and Novel Techniques. AAPS PharmSciTech 2025, 26, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, K.J.; Ganesan, M.; Tenchov, R.; Iyer, K.A.; Ralhan, K.; Diaz, L.L.; Bird, R.E.; Ivanov, J.; Zhou, Q.A. Nanoscience in Action: Unveiling Emerging Trends in Materials and Applications. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 7530–7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Chandrashekhar, H.R.; Day, C.M.; Garg, S.; Nayak, Y.; Shenoy, P.A.; Nayak, U.Y. Polymeric functionalization of mesoporous silica nanoparticles: Biomedical insights. Int J Pharm 2024, 660, 124314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, T.; Ji, Z.; Regmi, S.; Tong, H.; Ju, J.; Wang, A. Advances in microneedle-based drug delivery system for metabolic diseases: structural considerations, design strategies, and future perspectives. J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.G.; Surendran, S.P.; Jeong, Y.Y. Tumor Microenvironment-Stimuli Responsive Nanoparticles for Anticancer Therapy. Front Mol Biosci 2020, 7, 610533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, D.; Chen, Z. Biomedical applications of stimuli-responsive nanomaterials. MedComm (2020) 2024, 5, e643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, B.; Yu, L.; Yang, Y.; Guimaraes, C.F.; Xu, R.; Thambi, T.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, Q.; Reis, R.L. Light-stimulated smart thermo-responsive constructs for enhanced wound healing: A streamlined command approach. Asian J Pharm Sci 2025, 20, 101057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Zheng, Z.; Li, W.; Huang, C.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Liang, J.; et al. Advanced wound healing with Stimuli-Responsive nanozymes: mechanisms, design and applications. J Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; You, W.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Tang, Z.; Luo, Y.; Xiao, W.; Yang, Q.; Feng, M.; Li, L.; et al. Stimuli-responsive nanozymes for wound healing: From design strategies to therapeutic advances. Mater Today Bio 2025, 33, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venturini, J.; Chakraborty, A.; Baysal, M.A.; Tsimberidou, A.M. Developments in nanotechnology approaches for the treatment of solid tumors. Exp Hematol Oncol 2025, 14, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Mixich, L.; Boonstra, E.; Cabral, H. Polymer-Based mRNA Delivery Strategies for Advanced Therapies. Adv Healthc Mater 2023, 12, e2202688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Or-Rashid, M.; Aktar, M.N.; Hossain, M.S.; Sarkar, N.; Islam, M.R.; Arafat, M.E.; Bhowmik, S.; Yusa, S.I. Recent Advances in Micro- and Nano-Drug Delivery Systems Based on Natural and Synthetic Biomaterials. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.; Choi, M.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Sim, S.B.; Haizan, I.; Choi, J.H. Electrochemical Microneedles for Real-Time Monitoring in Interstitial Fluid: Emerging Technologies and Future Directions. Biosensors (Basel) 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zhou, Z.; Wolter, T.; Womelsdorf, J.; Somers, A.; Feng, Y.; Nuutila, K.; Tian, Z.; Chen, J.; Tamayol, A.; et al. Engineering microneedles for biosensing and drug delivery. Bioact Mater 2025, 52, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghib, S.M.; Ahmadi, B.; Mikaeeli Kangarshahi, B.; Mozafari, M.R. Chitosan-based smart stimuli-responsive nanoparticles for gene delivery and gene therapy: Recent progresses on cancer therapy. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 278, 134542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Guo, S.; Ravichandran, D.; Ramanathan, A.; Sobczak, M.T.; Sacco, A.F.; Patil, D.; Thummalapalli, S.V.; Pulido, T.V.; Lancaster, J.N.; et al. 3D-Printed Polymeric Biomaterials for Health Applications. Adv Healthc Mater 2025, 14, e2402571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirbubalo, M.; Tucak, A.; Muhamedagic, K.; Hindija, L.; Rahic, O.; Hadziabdic, J.; Cekic, A.; Begic-Hajdarevic, D.; Cohodar Husic, M.; Dervisevic, A.; et al. 3D Printing-A “Touch-Button” Approach to Manufacture Microneedles for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, H.; Zhao, S.; Chen, X.; Wei, T.; Peng, H.; Chen, Z. 3D-Printed Integrated Ultrasonic Microneedle Array for Rapid Transdermal Drug Delivery. Mol Pharm 2022, 19, 3314–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Nimry, S.S.; Daghmash, R.M. Three Dimensional Printing and Its Applications Focusing on Microneedles for Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLoughlin, C.D.; Nevins, S.; Stein, J.B.; Khakbiz, M.; Lee, K.B. Overcoming the Blood-Brain Barrier: Multifunctional Nanomaterial-Based Strategies for Targeted Drug Delivery in Neurological Disorders. Small Sci 2024, 4, 2400232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Hasan, A.; Mahdi Nejadi Babadaei, M.; Hashemi Kani, P.; Jouya Talaei, A.; Sharifi, M.; Cai, T.; Falahati, M.; Cai, Y. Polymeric-based microneedle arrays as potential platforms in the development of drugs delivery systems. J Adv Res 2020, 26, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, G.; Hou, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jia, J.; Chai, L.; Ma, C. Potential Biomedical Limitations of Graphene Nanomaterials. Int J Nanomedicine 2023, 18, 1695–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, K.W. Medical Applications of 3D Printing and Standardization Issues. Brain Tumor Res Treat 2023, 11, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilla, M.; Detamornrat, U.; Dominguez-Robles, J.; Tunca, S.; Donnelly, R.F.; De Wael, K. Wearable Microneedle-Based Array Patches for Continuous Electrochemical Monitoring and Drug Delivery: Toward a Closed-Loop System for Methotrexate Treatment. ACS Sens 2023, 8, 4161–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Peng, S.; He, S.; Tang, S.Y.; Goda, K.; Wang, C.H.; Li, M. Wearable Electrochemical Biosensors for Advanced Healthcare Monitoring. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2025, 12, e2411433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshandeh, F.; Zheng, H.; Barra, N.G.; Sadeghzadeh, S.; Ausri, I.; Sen, P.; Keyvani, F.; Rahman, F.; Quadrilatero, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Wearable Aptalyzer Integrates Microneedle and Electrochemical Sensing for In Vivo Monitoring of Glucose and Lactate in Live Animals. Adv Mater 2024, 36, e2313743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Pan, Z.; De Bock, M.; Tan, T.X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yan, N.; Yetisen, A.K. A wearable microneedle patch incorporating reversible FRET-based hydrogel sensors for continuous glucose monitoring. Biosens Bioelectron 2024, 262, 116542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.H.; Kim, J.H. Advances in Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Integrated Devices for Management of Diabetes with Insulin-Based Therapy: Improvement in Glycemic Control. Diabetes Metab J 2023, 47, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, R.; Cai, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.; Wu, L.; Liu, D.; et al. Artificial intelligence in diabetes management: Advancements, opportunities, and challenges. Cell Rep Med 2023, 4, 101213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdeva, S.; Bhatia, S.; Al Harrasi, A.; Shah, Y.A.; Anwer, K.; Philip, A.K.; Shah, S.F.A.; Khan, A.; Ahsan Halim, S. Unraveling the role of cloud computing in health care system and biomedical sciences. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elendu, C.; Elendu, T.C.; Elendu, I.D. 5G-enabled smart hospitals: Innovations in patient care and facility management. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024, 103, e38239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorlutuna, P.; Annabi, N.; Camci-Unal, G.; Nikkhah, M.; Cha, J.M.; Nichol, J.W.; Manbachi, A.; Bae, H.; Chen, S.; Khademhosseini, A. Microfabricated biomaterials for engineering 3D tissues. Adv Mater 2012, 24, 1782–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidian, H.; Dey Chowdhury, S. Swellable Microneedles in Drug Delivery and Diagnostics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, A.R.; Vondra, I. Biting Innovations of Mosquito-Based Biomaterials and Medical Devices. Materials (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbituyimana, B.; Adhikari, M.; Qi, F.; Shi, Z.; Fu, L.; Yang, G. Microneedle-based cell delivery and cell sampling for biomedical applications. J Control Release 2023, 362, 692–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Sediako, R.D.; Richter, B.; Blaicher, M.; Thiel, M.; Hermatschweiler, M. Industrial perspectives for personalized microneedles. Beilstein J Nanotechnol 2023, 14, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makvandi, P.; Jamaledin, R.; Chen, G.; Baghbantaraghdari, Z.; Zare, E.N.; Di Natale, C.; Onesto, V.; Vecchione, R.; Lee, J.; Tay, F.R.; et al. Stimuli-responsive transdermal microneedle patches. Mater Today (Kidlington) 2021, 47, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A.; Almotairy, A.R.Z.; Henidi, H.; Alshehri, O.Y.; Aldughaim, M.S. Nanoparticles as Drug Delivery Systems: A Review of the Implication of Nanoparticles’ Physicochemical Properties on Responses in Biological Systems. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, J.M.; Lim, Y.J.L.; Tay, J.T.; Cheng, H.M.; Tey, H.L.; Liang, K. Design and fabrication of customizable microneedles enabled by 3D printing for biomedical applications. Bioact Mater 2024, 32, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, S.; Iftikhar, F.J.; Shah, A.; Rehman, H.A.; Iwuoha, E. Novel interfaces for internet of wearable electrochemical sensors. RSC Adv 2024, 14, 36713–36732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, Q.T.; Seo, J.W.; Charoensri, K.; Nguyen, M.H.; Park, H.J.; Bae, H. 4D-printed microneedles from dual-sensitive chitosan for non-transdermal drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 261, 129638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, A.; Agostinho Cordeiro, M.; Mendes, M.; Marques Ribeiro, M.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F.; Vitorino, C. Additive manufacturing of microneedles: a quality by design approach to clinical translation. Int J Pharm 2025, 687, 126399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, R.F.; Machado, P.; Rodrigues, R.O.; Faustino, V.; Schutte, H.; Gassmann, S.; Lima, R.A.; Minas, G. Recent advances and perspectives of MicroNeedles for biomedical applications. Biophys Rev 2025, 17, 909–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, D.A.; Vidal, R.M.; Velasco, J.; Carreno, L.J.; Torres, J.P.; Benachi, O.M.; Tovar-Rosero, Y.Y.; Onate, A.A.; O’Ryan, M. Two centuries of vaccination: historical and conceptual approach and future perspectives. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1326154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, I.; Bagwe, P.; Gomes, K.B.; Bajaj, L.; Gala, R.; Uddin, M.N.; D’Souza, M.J.; Zughaier, S.M. Microneedles: A New Generation Vaccine Delivery System. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Liu, J.; Shi, M.; Abbas, M.; Xing, R.; Yan, X. Microneedle delivery systems for vaccines and immunotherapy. Smart Mol 2025, 3, e20240067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.X. Beyond the Needle: Innovative Microneedle-Based Transdermal Vaccination. Medicines (Basel) 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddio, A.; Appleton, M.; Bortolussi, R.; Chambers, C.; Dubey, V.; Halperin, S.; Hanrahan, A.; Ipp, M.; Lockett, D.; MacDonald, N.; et al. Reducing the pain of childhood vaccination: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline. CMAJ 2010, 182, E843-855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campa, C.; Pronce, T.; Paludi, M.; Weusten, J.; Conway, L.; Savery, J.; Richards, C.; Clenet, D. Use of Stability Modeling to Support Accelerated Vaccine Development and Supply. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrowsky, J.T.; Vestin, N.C.; Mehr, A.J.; Ulrich, A.K.; Bigalke, L.; Bresee, J.S.; Friede, M.H.; Gellin, B.G.; Klugman, K.P.; Nakakana, U.N.; et al. Accomplishments and challenges in developing improved influenza vaccines: An evaluation of three years of progress toward the milestones of the influenza vaccines research and development roadmap. Vaccine 2025, 61, 127431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Song, H.; Sun, T.; Wang, H. Responsive Microneedles as a New Platform for Precision Immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonla, C.; Reynoso, M.; Chang, A.Y.; Saha, T.; Surace, S.; Wang, J. Microneedle-Based Multiplexed Monitoring of Diabetes Biomarkers: Capabilities Beyond Glucose Toward Closed-Loop Theranostic Systems. ACS Sens 2025, 10, 5363–5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olukorode, J.O.; Orimoloye, D.A.; Nwachukwu, N.O.; Onwuzo, C.N.; Oloyede, P.O.; Fayemi, T.; Odunaike, O.S.; Ayobami-Ojo, P.S.; Divine, N.; Alo, D.J.; et al. Recent Advances and Therapeutic Benefits of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Agonists in the Management of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Metabolic Disorders. Cureus 2024, 16, e72080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodring, R.N.; Gurysh, E.G.; Bachelder, E.M.; Ainslie, K.M. Drug Delivery Systems for Localized Cancer Combination Therapy. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2023, 6, 934–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G. Principles of general diagnosis in blood platelet deficiency syndromes. Minerva Pediatr 1972, 24, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Sareen, G.; Mohan, M.; Mannan, A.; Dua, K.; Singh, T.G. A new era of cancer immunotherapy: vaccines and miRNAs. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2025, 74, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M.S.; Lee, J.M.; Jo, M.J.; Kang, S.J.; Yoo, M.K.; Park, S.Y.; Bong, S.; Park, C.S.; Park, C.W.; Kim, J.S.; et al. Dual-Drug Delivery Systems Using Hydrogel-Nanoparticle Composites: Recent Advances and Key Applications. Gels 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, J.Y.; Terry, R.N.; Tang, J.; Romanyuk, A.; Schwendeman, S.P.; Prausnitz, M.R. Core-shell microneedle patch for six-month controlled-release contraceptive delivery. J Control Release 2022, 347, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Perez, L.E.; Alvarez, M.; Dilla, T.; Gil-Guillen, V.; Orozco-Beltran, D. Adherence to therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther 2013, 4, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Jian, X.; Yu, B. Review of Applications of Microneedling in Melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol 2025, 24, e16707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Niu, B.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Zhu, P.; Meng, F. Research progress of dissolving microneedles in the field of component administration of traditional Chinese medicine. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1623476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.H.; Zheng, L.; Wang, Z. mRNA therapeutics: New vaccination and beyond. Fundam Res 2023, 3, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Mehmood, S.; Raza, A.; Hayat, U.; Rasheed, T.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Microneedles in Smart Drug Delivery. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2021, 10, 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojekar, S.; Vora, L.K.; Tekko, I.A.; Volpe-Zanutto, F.; McCarthy, H.O.; Vavia, P.R.; Donnelly, R.F. Etravirine-loaded dissolving microneedle arrays for long-acting delivery. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2021, 165, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Crudden, M.T.C.; Larrañeta, E.; Clark, A.; Jarrahian, C.; Rein-Weston, A.; Lachau-Durand, S.; Niemeijer, N.; Williams, P.; Haeck, C.; McCarthy, H.O.; et al. Design, formulation and evaluation of novel dissolving microarray patches containing a long-acting rilpivirine nanosuspension. J Control Release 2018, 292, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffatt, K.; Tekko, I.A.; Vora, L.; Volpe-Zanutto, F.; Hutton, A.R.J.; Mistilis, J.; Jarrahian, C.; Akhavein, N.; Weber, A.D.; McCarthy, H.O.; et al. Development and Evaluation of Dissolving Microarray Patches for Co-administered and Repeated Intradermal Delivery of Long-acting Rilpivirine and Cabotegravir Nanosuspensions for Paediatric HIV Antiretroviral Therapy. Pharm. Res. 2023, 40, 1673–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, Y.; Hutton, A.R.J.; Hidayat Bin Sabri, A.; Hobson, J.J.; Savage, A.C.; McCarthy, H.O.; Paredes, A.J.; Owen, A.; Rannard, S.P.; et al. Systemic delivery of bictegravir and tenofovir alafenamide using dissolving microneedles for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Int. J. Pharm 2024, 660, 124317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Song, Y. Recent advances of microneedles for biomedical applications: drug delivery and beyond. Acta Pharm Sin B 2019, 9, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Xie, S.; Li, Z.; Dong, S.; Teng, L. Precise nanoscale fabrication technologies, the “last mile” of medicinal development. Acta Pharm Sin B 2025, 15, 2372–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartawi, Z.; Blackshields, C.; Faisal, W. Dissolving microneedles: Applications and growing therapeutic potential. J Control Release 2022, 348, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, J.M.; Andrade Del Olmo, J.; Perez Gonzalez, R.; Saez-Martinez, V. Injectable Hydrogels: From Laboratory to Industrialization. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sati, A.; Mali, S.N.; Samdani, N.; Annadurai, S.; Dongre, R.; Satpute, N.; Ranade, T.N.; Pratap, A.P. From Past to Present: Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) in Daily LifeSynthesis Mechanisms, Influencing Factors, Characterization, Toxicity, and Emerging Applications in Biomedicine, Nanoelectronics, and Materials Science. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 33999–34087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, G.; Yao, X.; Zhou, H.; Lyu, B.; Pei, S.; Wen, P. Microneedle-based insulin transdermal delivery system: current status and translation challenges. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2022, 12, 2403–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, C.M.; Gianchecchi, E.; Montomoli, E. Influenza vaccines: Evaluation of the safety profile. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2018, 14, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.E.; Bettencourt, A.; Ribeiro, H.M. The regulatory challenges of innovative customized combination products. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 821094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Norman, G.A. Drugs, Devices, and the FDA: Part 1: An Overview of Approval Processes for Drugs. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2016, 1, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, P.; Jain, R.; Rosenkrands-Lange, E.; Hey, C.; Koban, M.U. Regulatory Pathways Supporting Expedited Drug Development and Approval in ICH Member Countries. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2023, 57, 484–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryakova, T.H.; Pogostin, B.H.; Langer, R.; McHugh, K.J. Overcoming barriers to patient adherence: the case for developing innovative drug delivery systems. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2023, 22, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammarano, A.; Dello Iacono, S.; Battisti, M.; De Stefano, L.; Meglio, C.; Nicolais, L. A systematic review of microneedles technology in drug delivery through a bibliometric and patent overview. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghafian, M.; Laumann, K.; Skogstad, M.R. Stagewise Overview of Issues Influencing Organizational Technology Adoption and Use. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 630145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.X.; Nguyen, C.N. Microneedle-Mediated Transdermal Delivery of Biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J.; Haigh, C.; Ahmed, T.; Uddin, M.J.; Das, D.B. Potential of Microneedle Systems for COVID-19 Vaccination: Current Trends and Challenges. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmam, B.; Salwa; Yarlagadda, D.L.; Gurram, P.C.; Kumar, L.; Shenoy, R.R.; Lewis, S.A. Dissolving Microneedle Patch Incorporated with Insulin Nanoparticles for The Management of Type-I Diabetes Mellitus: Formulation Development and in Vivo Monitoring. Adv Pharm Bull 2025, 15, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A.M.; Ameri, M.; Lewis, H.; Kellerman, D.J. Development of a novel zolmitriptan intracutaneous microneedle system (Qtrypta) for the acute treatment of migraine. Pain Manag 2020, 10, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.Y.; Han, D.; Yoon, K.Y.; Jeong, D.H.; Park, Y.I. Clinical Safety and Efficacy Evaluation of a Dissolving Microneedle Patch Having Dual Anti-Wrinkle Effects With Safe and Long-Term Activities. Ann Dermatol 2024, 36, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yu, J.; Gu, Z. Glucose-Responsive Microneedle Patches for Diabetes Treatment. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2019, 13, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacharodi, A.; Singh, P.; Meenatchi, R.; Tawfeeq Ahmed, Z.H.; Kumar, R.R.S.; V, N.; Kavish, S.; Maqbool, M.; Hassan, S. Revolutionizing healthcare and medicine: The impact of modern technologies for a healthier future-A comprehensive review. Health Care Sci 2024, 3, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jang, S.; Yu, S.; Ahn, Y.R.; Kim, M.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.O. Microneedle-nanoparticle hybrid platforms for metabolic syndrome: advances in point-of-care diagnostics and transdermal therapeutics. Discov Nano 2025, 20, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.C.; Collins, M.L.; Rota, P.A.; Prausnitz, M.R. Thermostability of Measles and Rubella Vaccines in a Microneedle Patch. Adv Ther (Weinh) 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avcil, M.; Celik, A. Microneedles in Drug Delivery: Progress and Challenges. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Ghosh, A.; Patel, V.; Peng, B.; Mendes, B.B.; Win, E.H.A.; Delogu, L.G.; Wong, J.Y.; Pischel, K.J.; Bellare, J.R.; et al. Voices of Nanomedicine: Blueprint Guidelines for Collaboration in Addressing Global Unmet Medical Needs. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 2979–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.L.; Lopez, O. Outlook on Industry-Academia-Government Collaborations Impacting Medical Device Innovation. J Eng Sci Med Diagn Ther 2024, 7, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Fabrication materials/methods | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid | Silicon, metals, polymers, etching, molding | Creates microchannels for passive diffusion | Simple design, low cost | Poor control of dosing | [12] |

| Coated | Dip-coating, spray-coating, and inkjet printing | Drug layered on the surface, dissolves upon insertion | Rapid release, suited for vaccines | Limited drug load | [18] |

| Dissolving | Polymers (polyvinylpyrrolidone, hyaluronic acid) via micro molding | The biodegradable matrix dissolves in the skin, releasing the drug | No waste, suitable for biologics | Fragility, limited penetration | [35] |

| Hollow | Silicon, glass, stainless steel; laser micromachining | Drug infused through the central lumen | Larger volumes, controlled infusion | Complex design, higher cost | [36] |

| Hydrogel-forming | Crosslinked polymers (PEG, PHEMA) | Swellable polymers form drug-permeable conduits | Sustained release, reusable reservoir | Removal required, slower onset | [37,38] |

| Hybrid/Next-gen | Composite polymers, 3D printing, NPs | Combines multiple features; smart materials | High versatility, personalized therapy | Still experimental, scalability issues | [39] |

| Innovation | Feature | Application | Advantage | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimuli-responsive MNs | pH, glucose, temperature-sensitive polymers | Insulin, targeted cancer therapy | On-demand, closed-loop release | glucose-responsive insulin MN patches for insulin delivery; pH-responsive MNs releasing doxorubicin or cisplatin selectively in acidic tumor tissue in murine xenograft models | [90] |

| Nanoparticle-loaded MNs | Drug-loaded nanoparticles or liposomes | Vaccines, biologics, gene therapy | Improved stability, targeted delivery | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticle-loaded MNs for influenza or SARS-CoV-2 subunit/DNA vaccines, showing enhanced humoral and cellular immunity vs intramuscular injection | [91] |

| 3D-printed MNs | Customized geometry, multi-layered | Personalized medicine, combination therapy | High precision, rapid prototyping | 3D-printed hollow MNs for individualized intradermal vaccination and sampling | [92] |

| Wearable MN patches | Integrated sensors and electronics | Chronic disease monitoring, digital health | Remote monitoring, automated dosing | Wearable MN patch from UC San Diego monitoring glucose, alcohol, and lactate simultaneously in interstitial fluid with electrochemical readout and wireless transmission | [93] |

| Hybrid MNs | Combination of dissolving, solid, hydrogel | Multi-drug or sequential release | Optimized pharmacokinetics, patient-tailored therapy | Hybrid dissolving–hydrogel MNs for biphasic release of small molecules such as ibuprofen (fast initial release from dissolving tips followed by sustained release from swelling base | [13] |

| MN Type | Product/Company | Therapeutic Area | Status/Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid/coated | Vaxxas Micro-Needle Array Patch | Influenza vaccine | Phase II/III trials; strong immunogenicity, dose sparing | [100] |

| Dissolving | 3M Microneedle Patch | Influenza, COVID-19 vaccines | Clinical trials; thermostable, self-administered | [135] |

| Dissolving | Micron Biomedical MN Patch | Insulin | Preclinical & early human trials; sustained release demonstrated | [136] |

| Hollow | Zosano Pharma Qtrypta | Migraine (zolmitriptan) | FDA approved; commercial availability in select regions | [137] |

| Dissolving/hybrid | Teva/BD Microneedle Platform | Hormonal therapy | Early-stage clinical trials; ongoing safety evaluation | [138] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).