Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Situation:

1.2. Emerging Perspectives and Alternatives:

| Characteristics | Fixed valves (preset pressure | Magnetic programmable valves (current) | Electronic / smart valves (in development |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRI compatibility | No problem (no magnetic components) | Yes, up to 3 Tesla (with anti-deregulation locking mechanisms) | Potentially sensitive, depends on shielding and electronic components (under evaluation) |

| Risk of over/under drainage | High (no adaptation possible) | Reduced thanks to adaptability and anti-siphon devices | Theoretically minimal, because automatic adjustment possible |

| Invasiveness | Impossible adjustment surgery necessary | Non-invasive adjustment by external programmer | Non-invasive adjustment, possibility of real-time monitoring |

| Monitoring | Clinical and radiological monitoring only | Clinical, radiological and sometimes radiographic to confirm the setting | Wireless telemetry possible, continuous intracranial pressure measurements [17,18] |

| Reliability / robustness | Very robust, few internal mechanisms | High reliability, improved since 2000 with anti-deregulation systems | Less clinical hindsight, risk of electronic breakdowns |

| Clinical availability | Still in use but in decline | Current standard in neurosurgery | Limited to research or clinical trials |

2. Materials and Methods

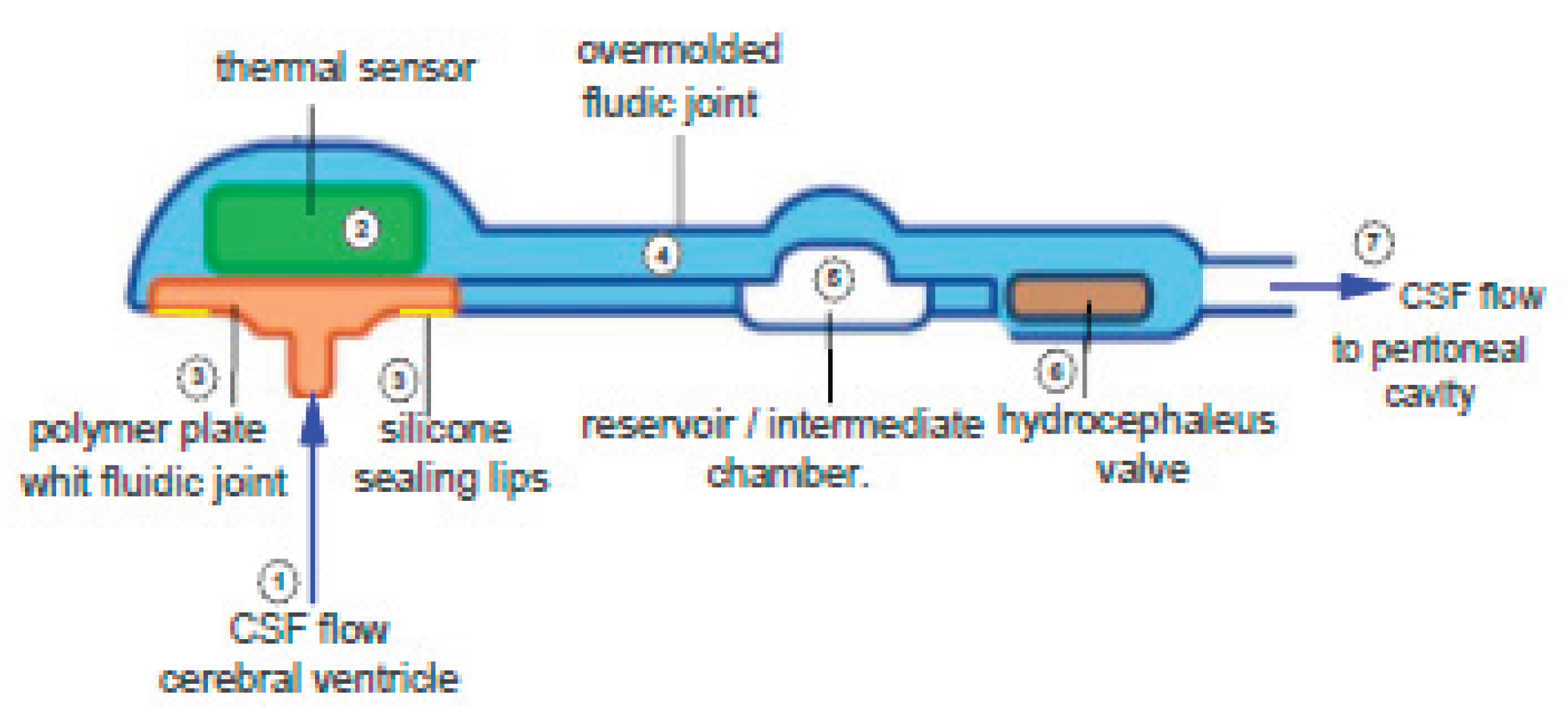

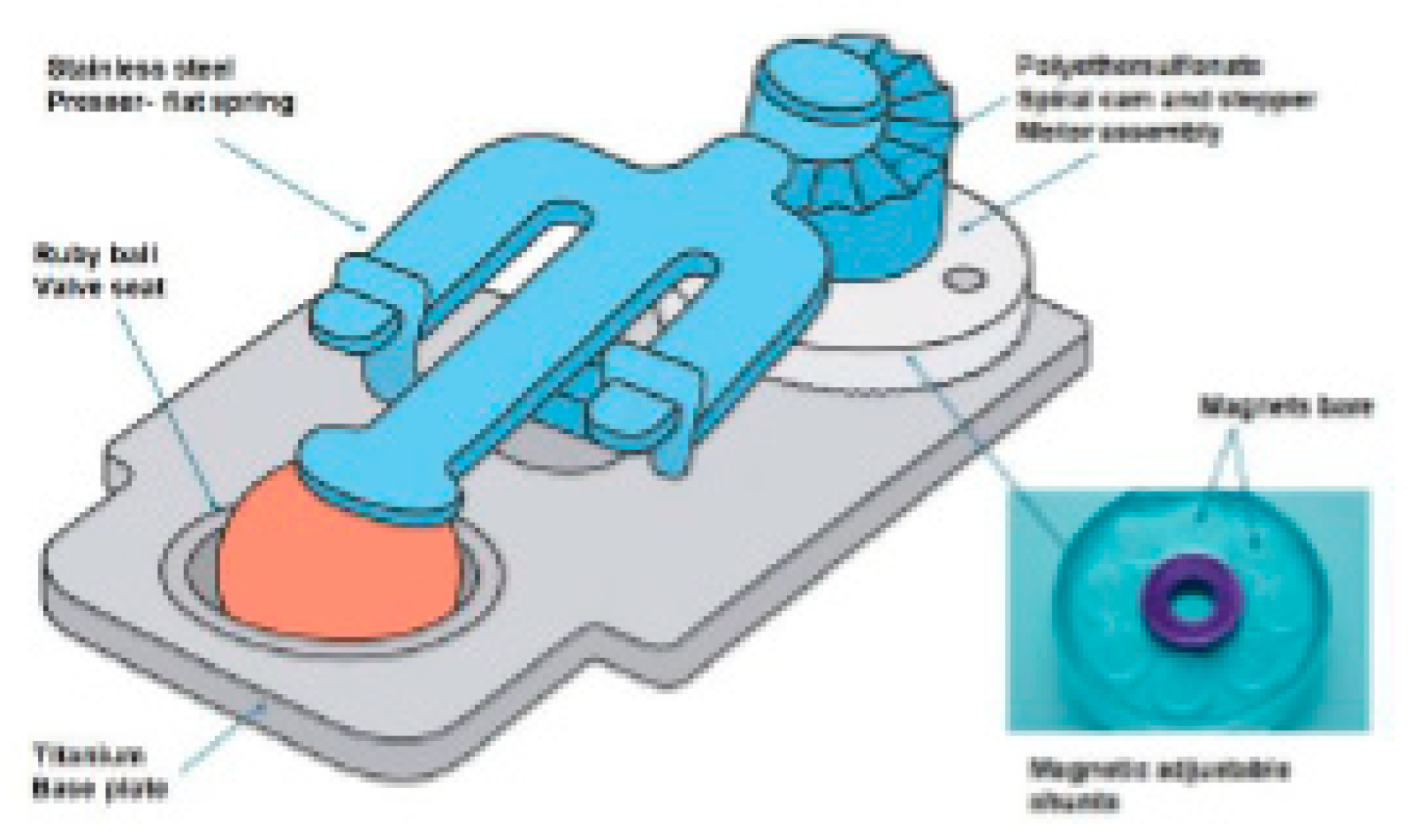

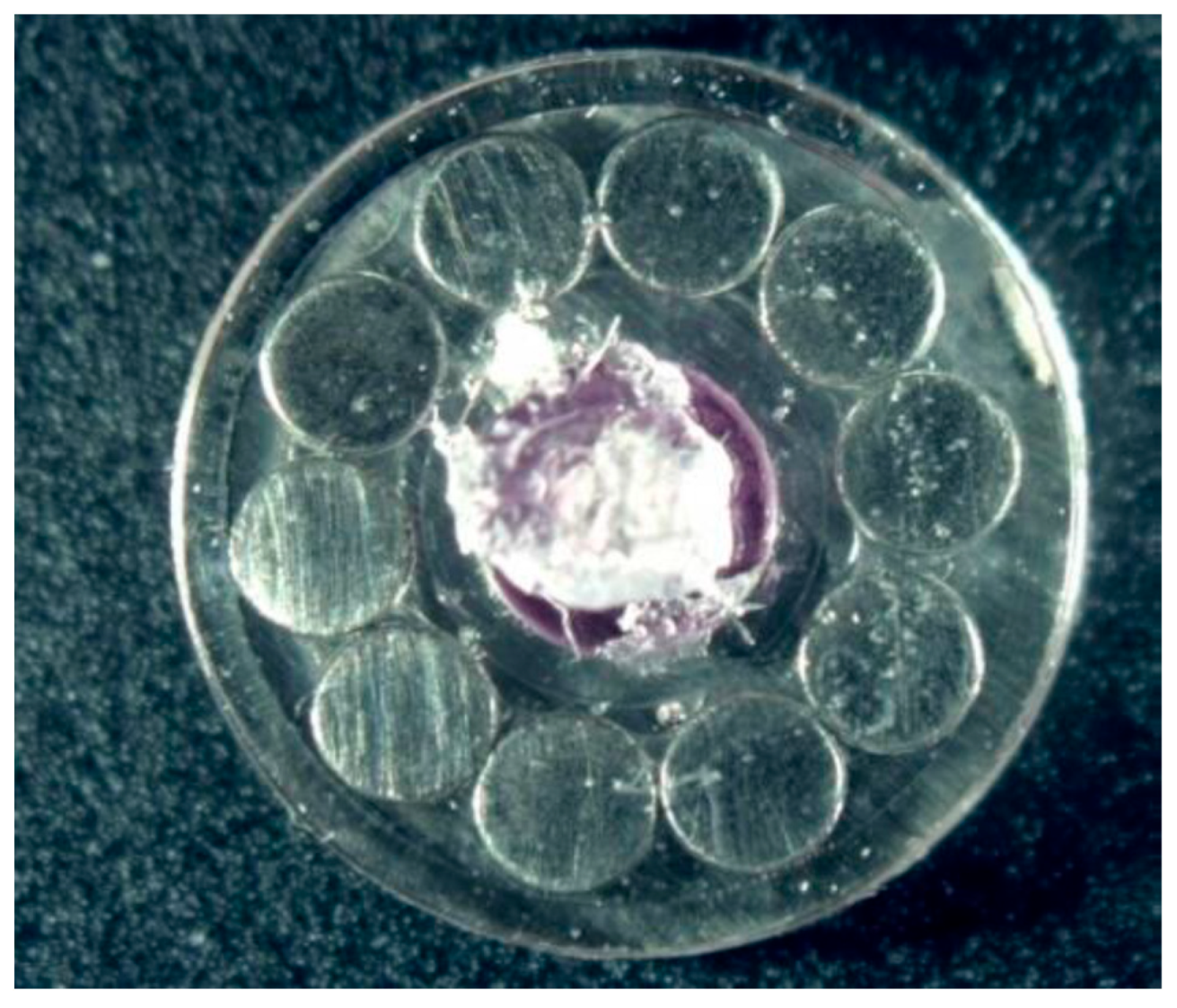

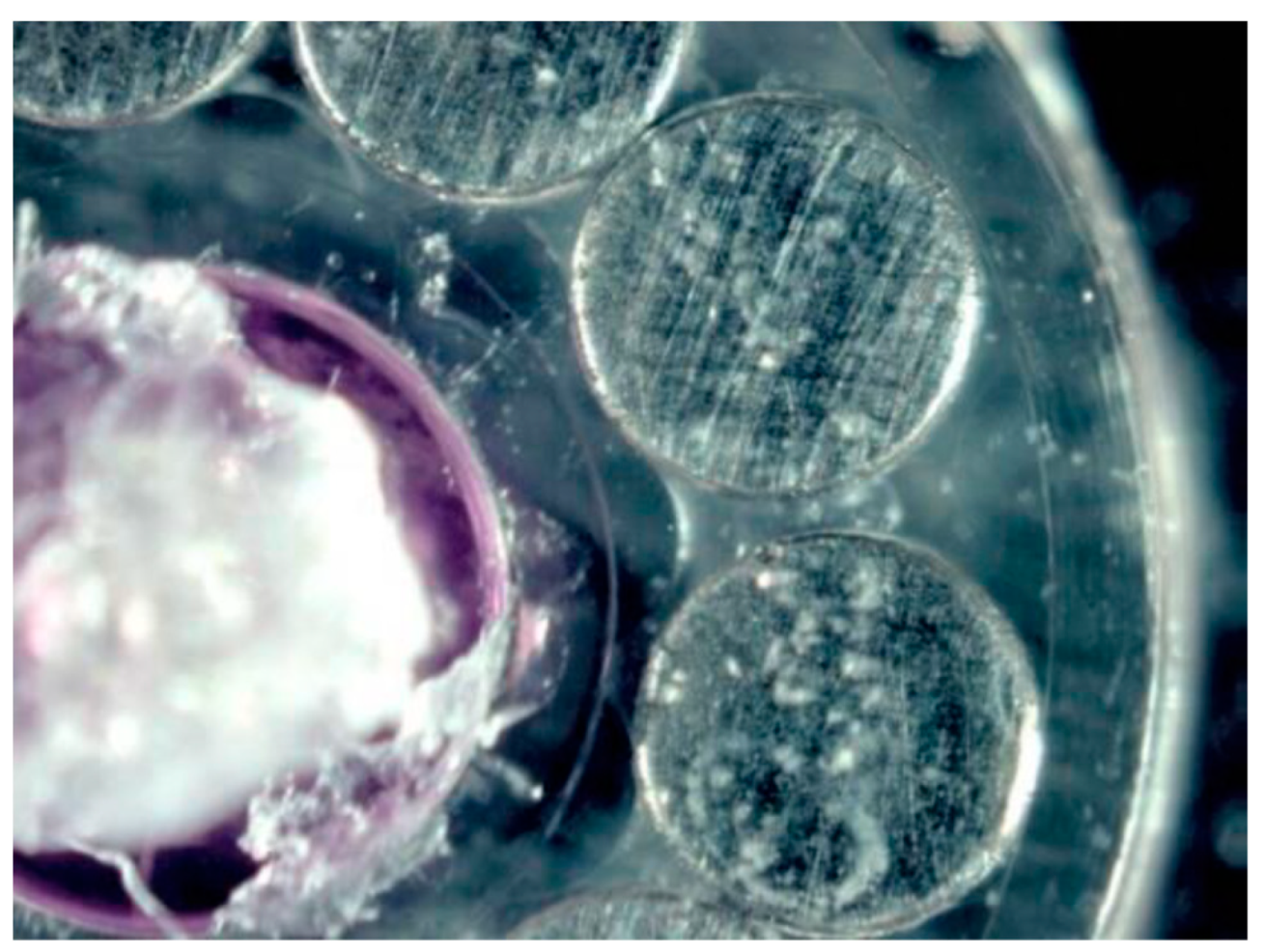

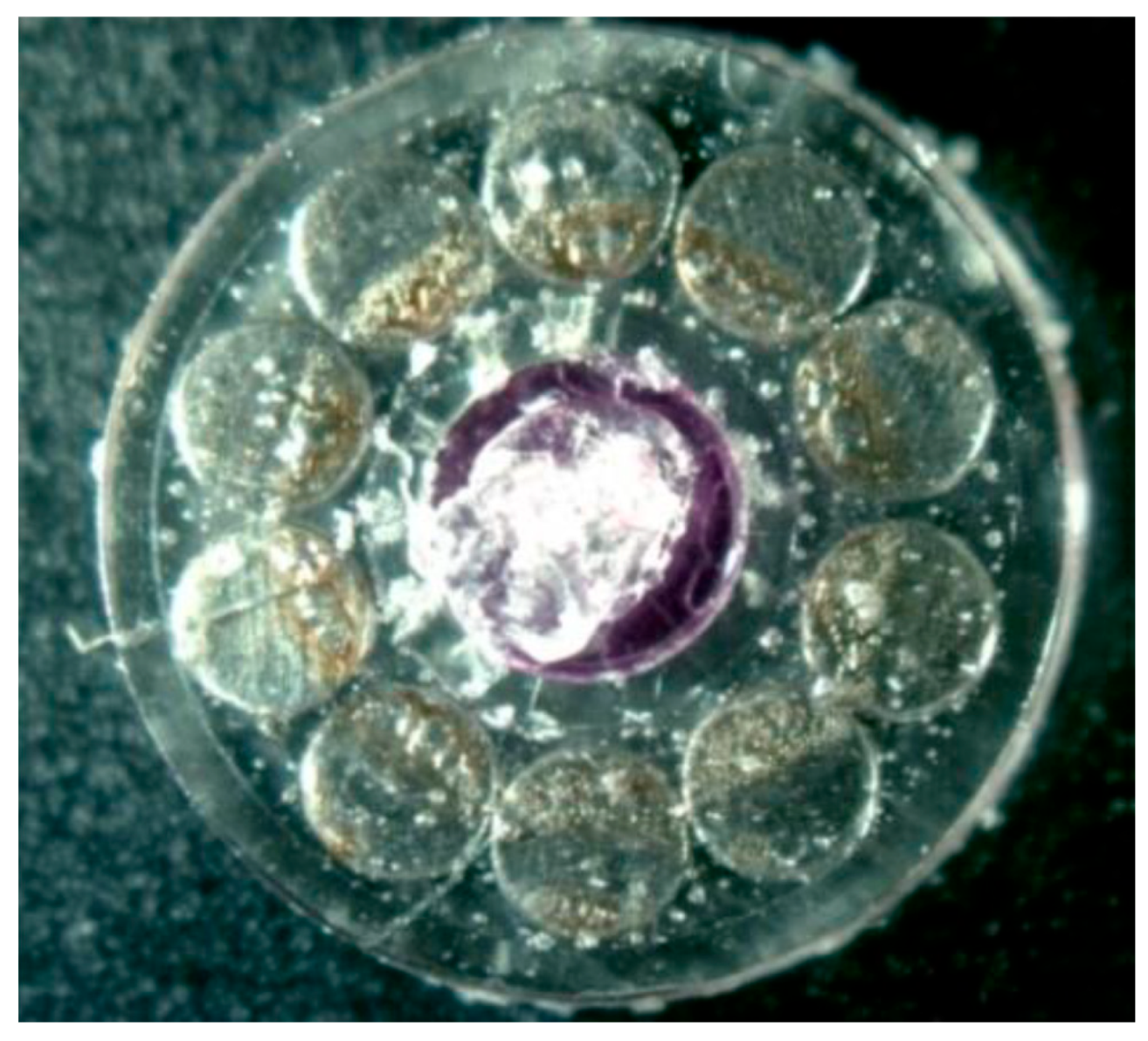

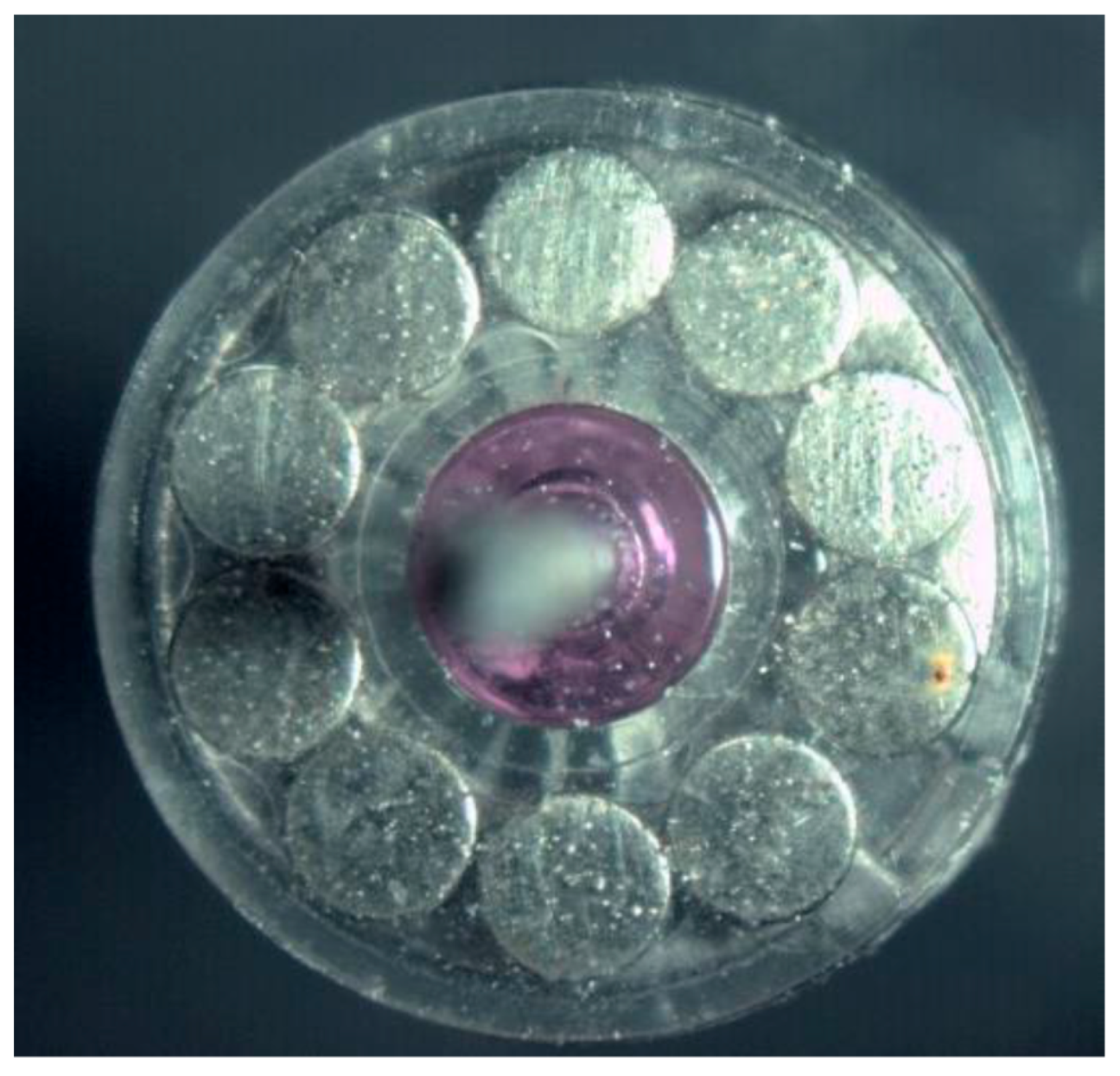

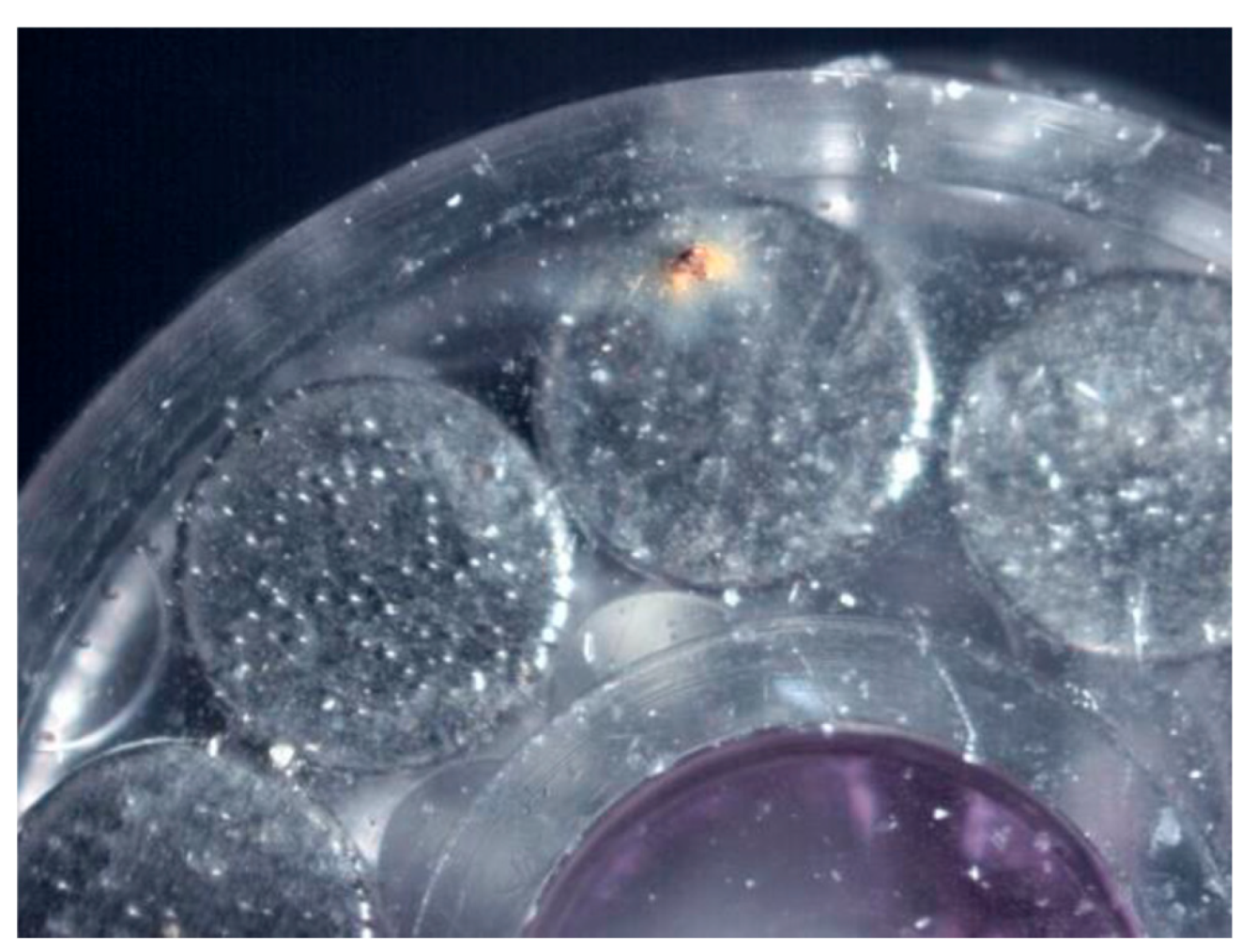

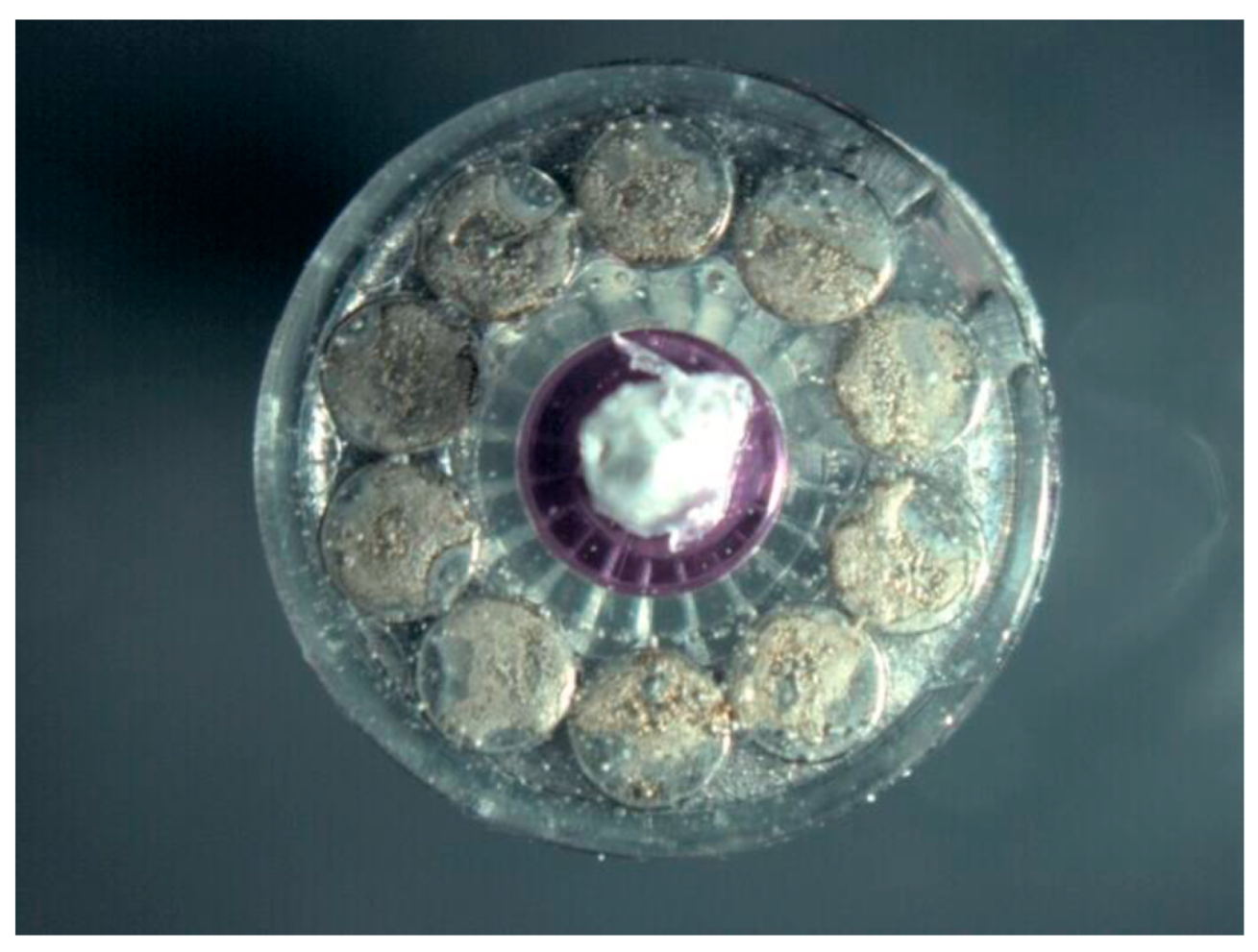

2.1. Integrated Device for Hydrocephaleus

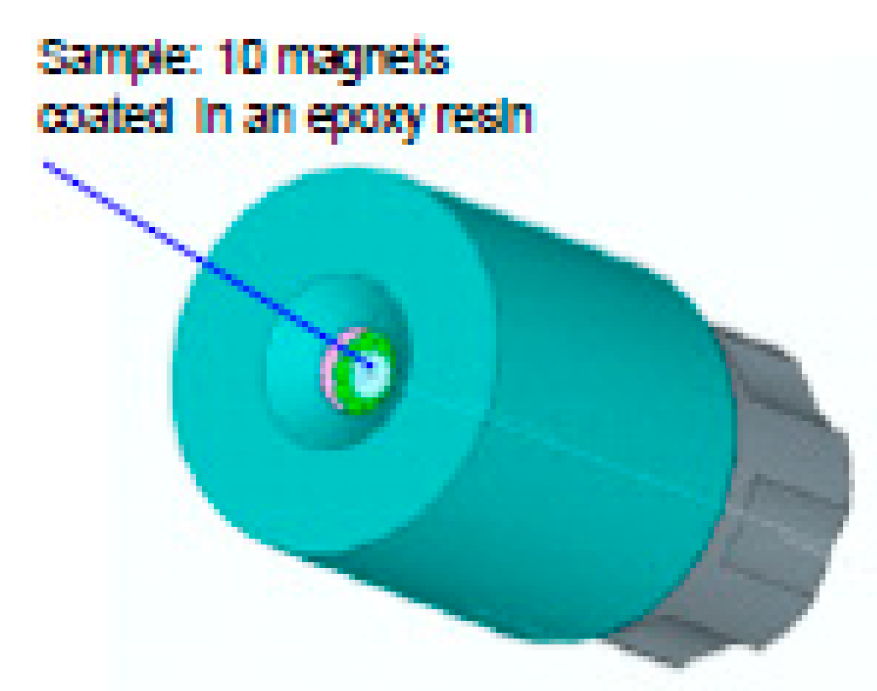

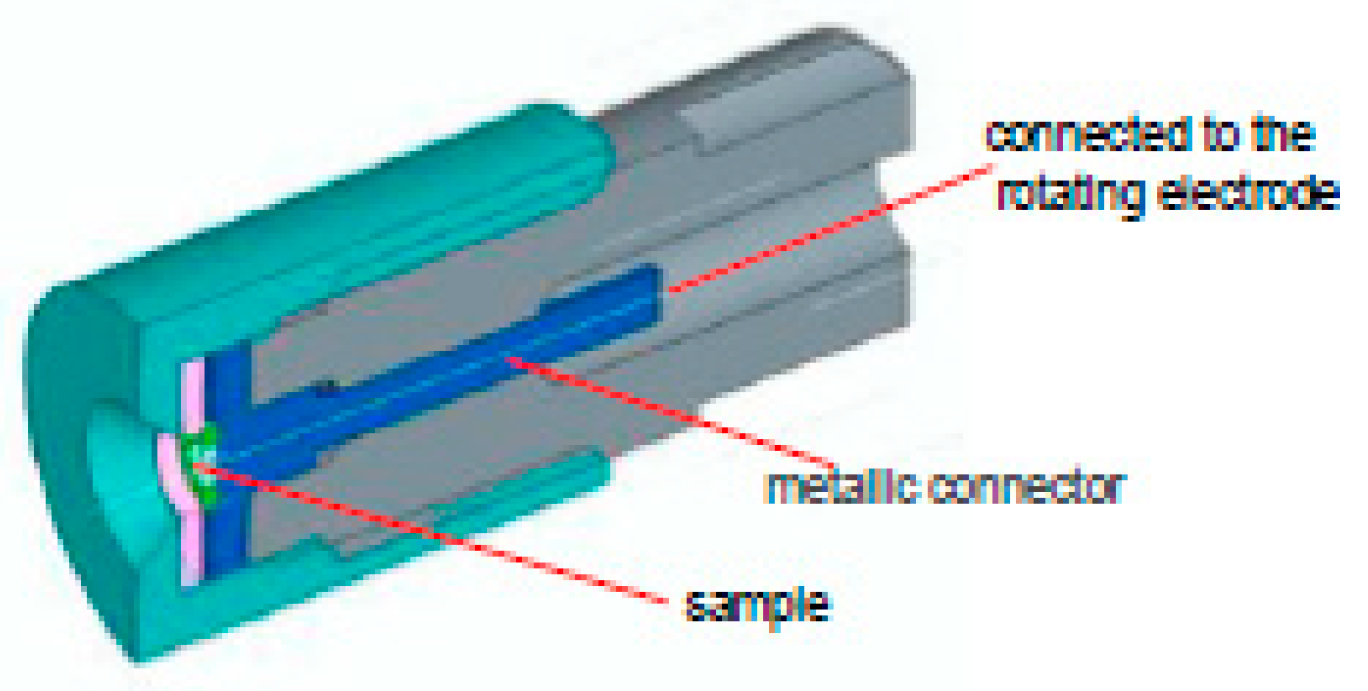

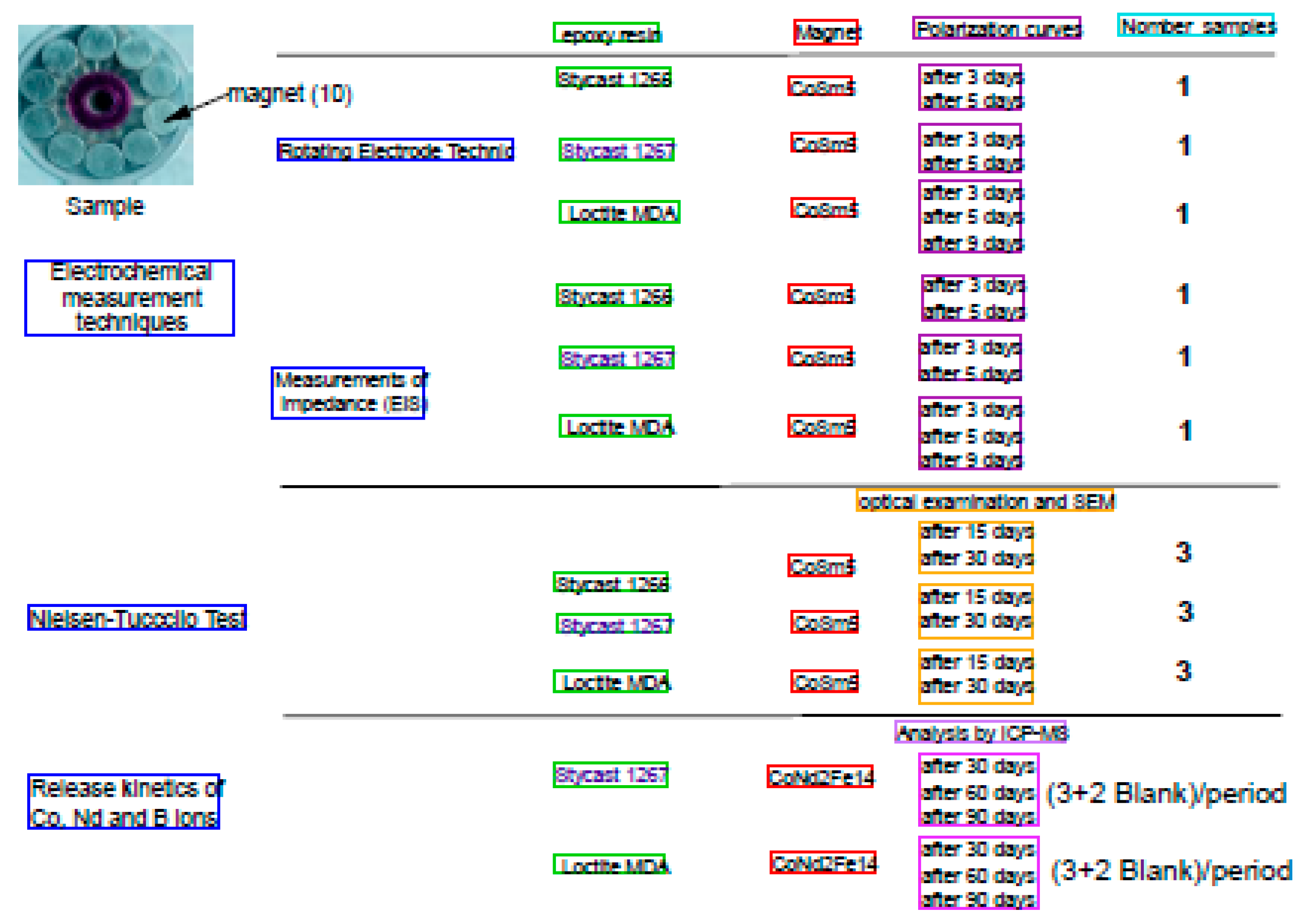

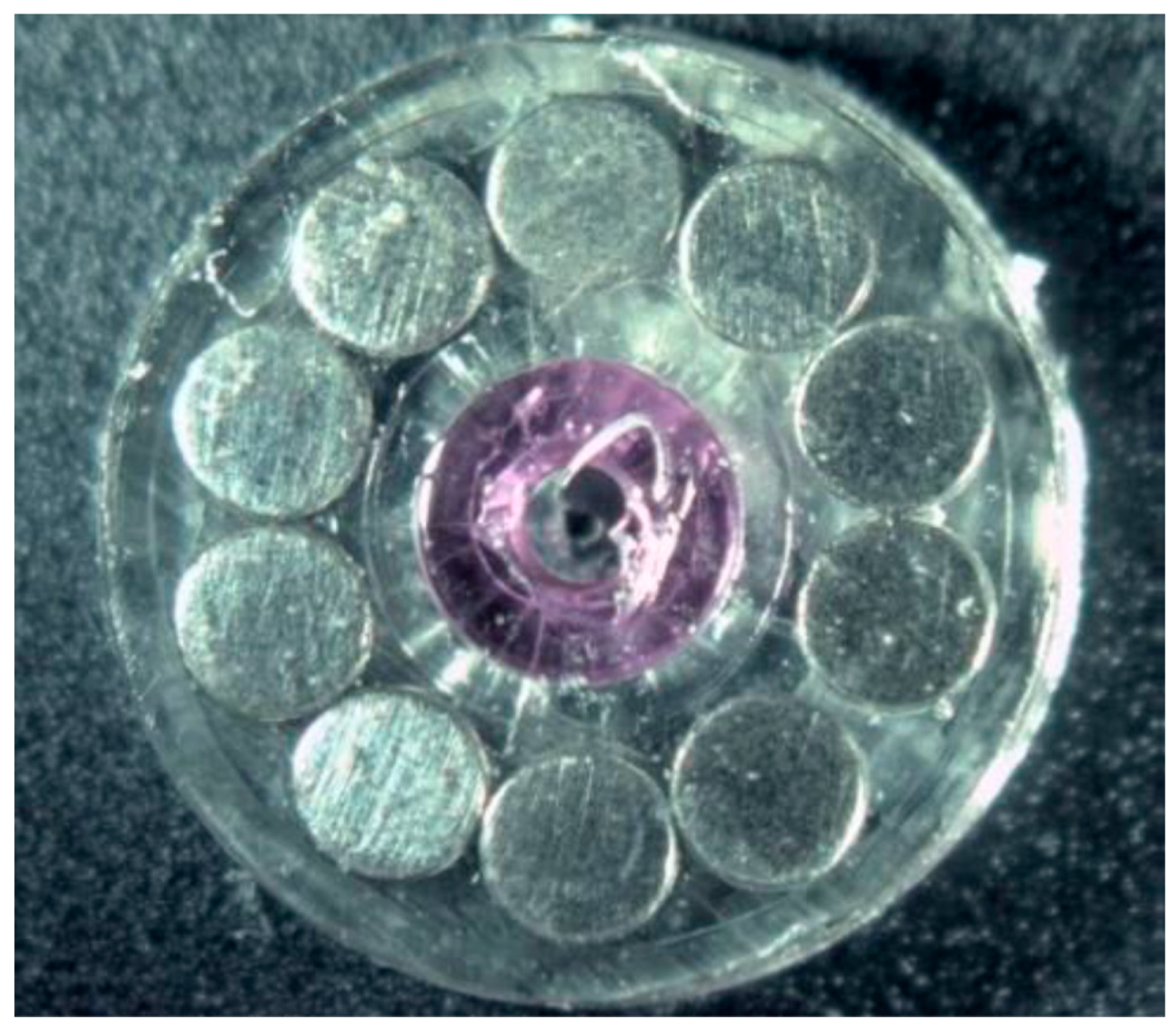

2.2. Samples

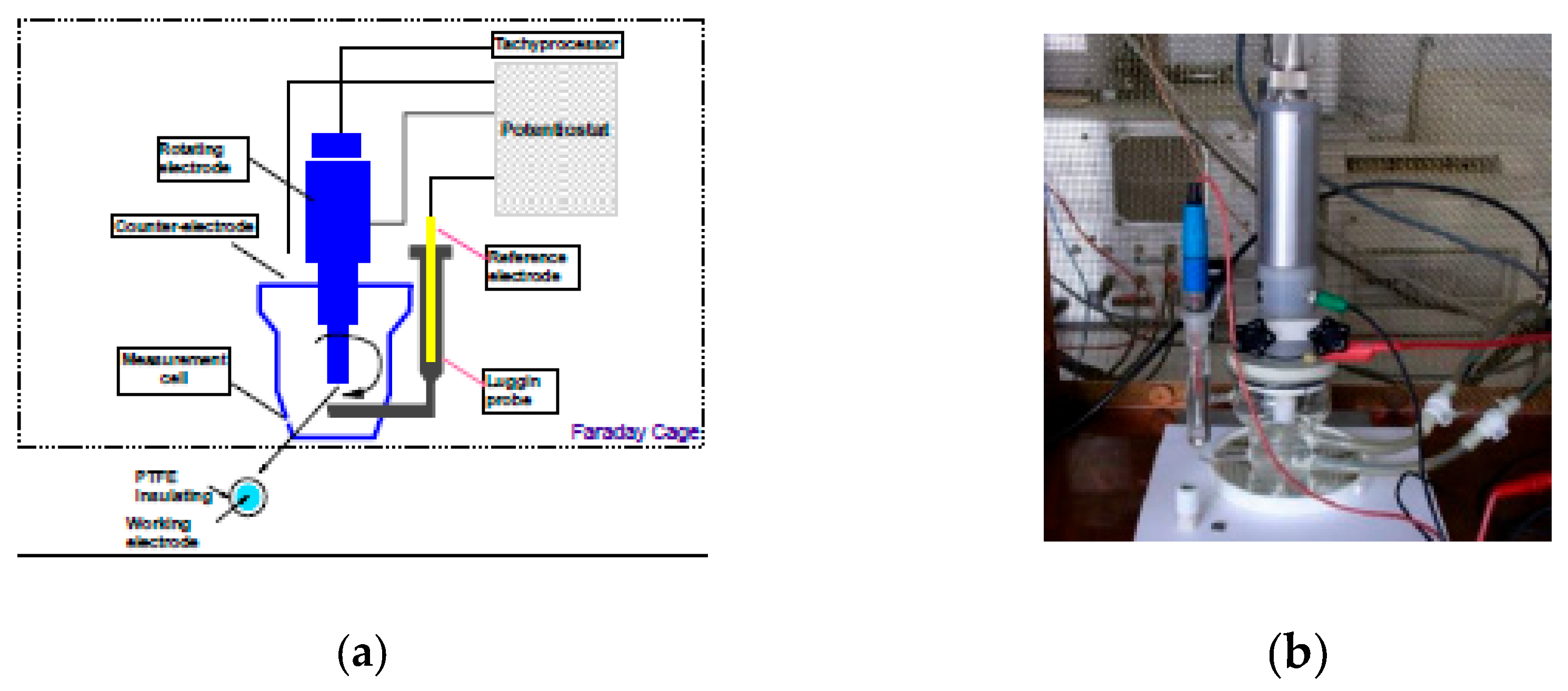

2.3. Electrochemical Measurement Techniques:

2.4. Nielsen-Tuccillo Test.

2.5. Kinetics of Release on Encapsulated Magnets.

3. Results and Discussion:

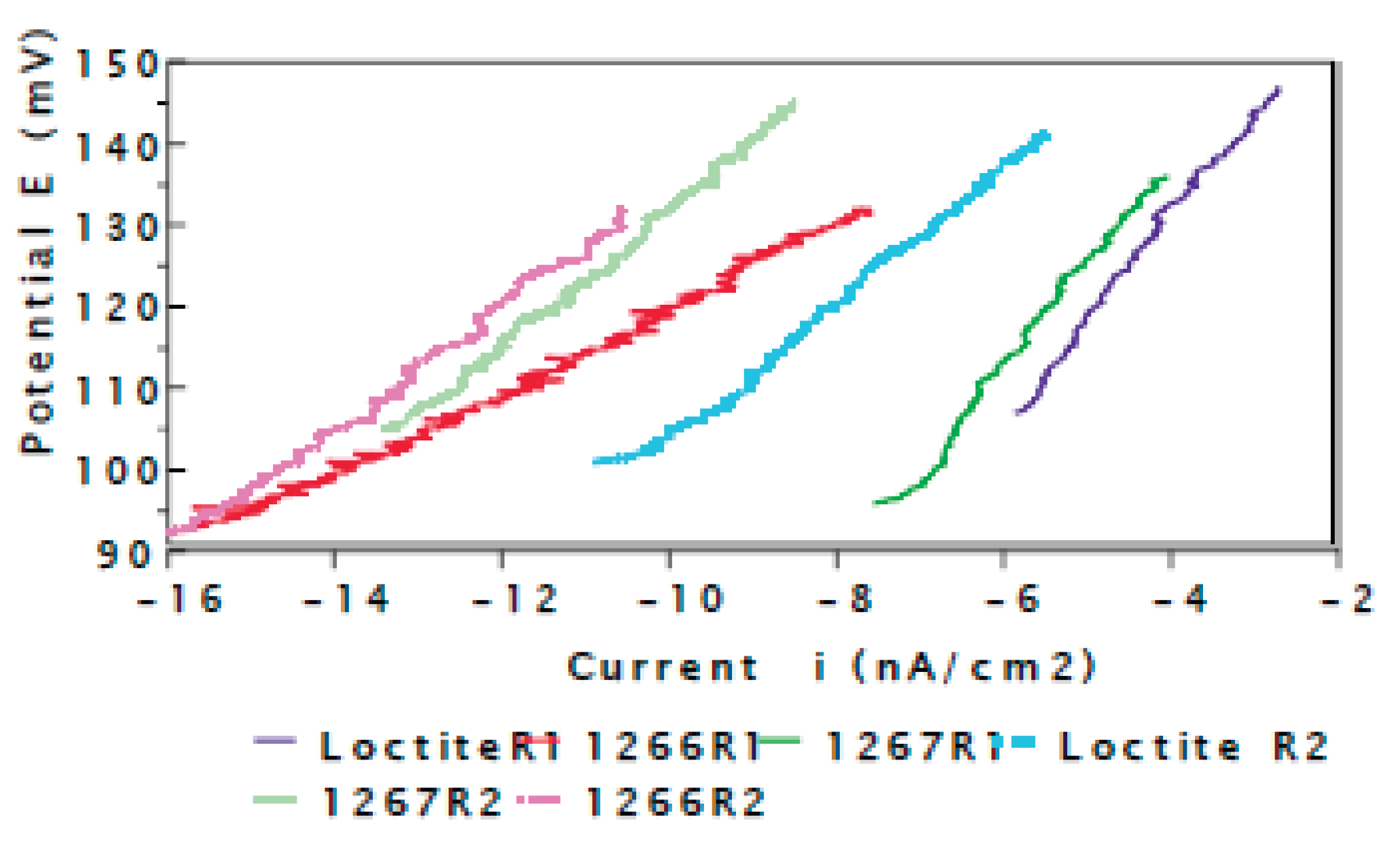

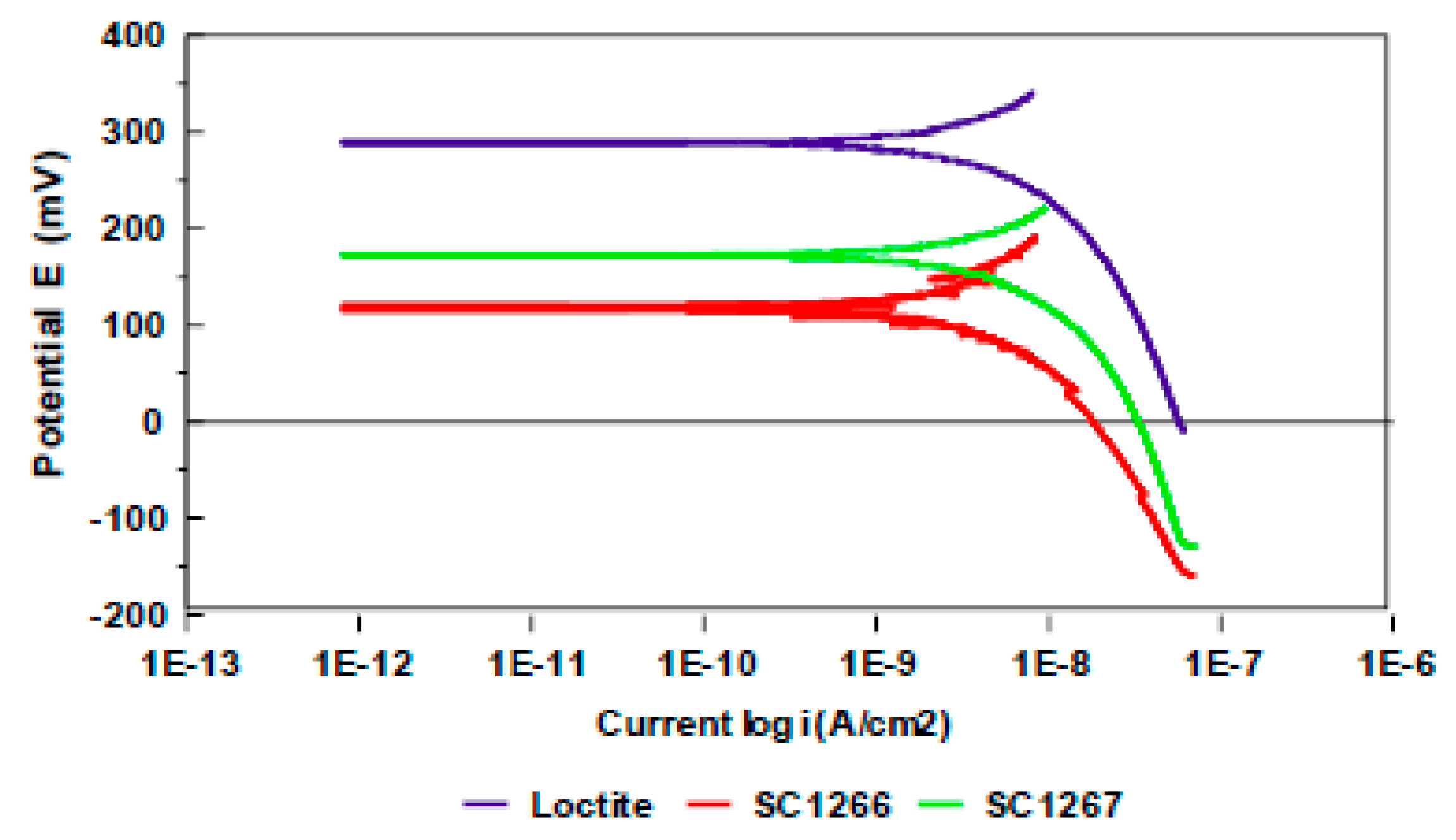

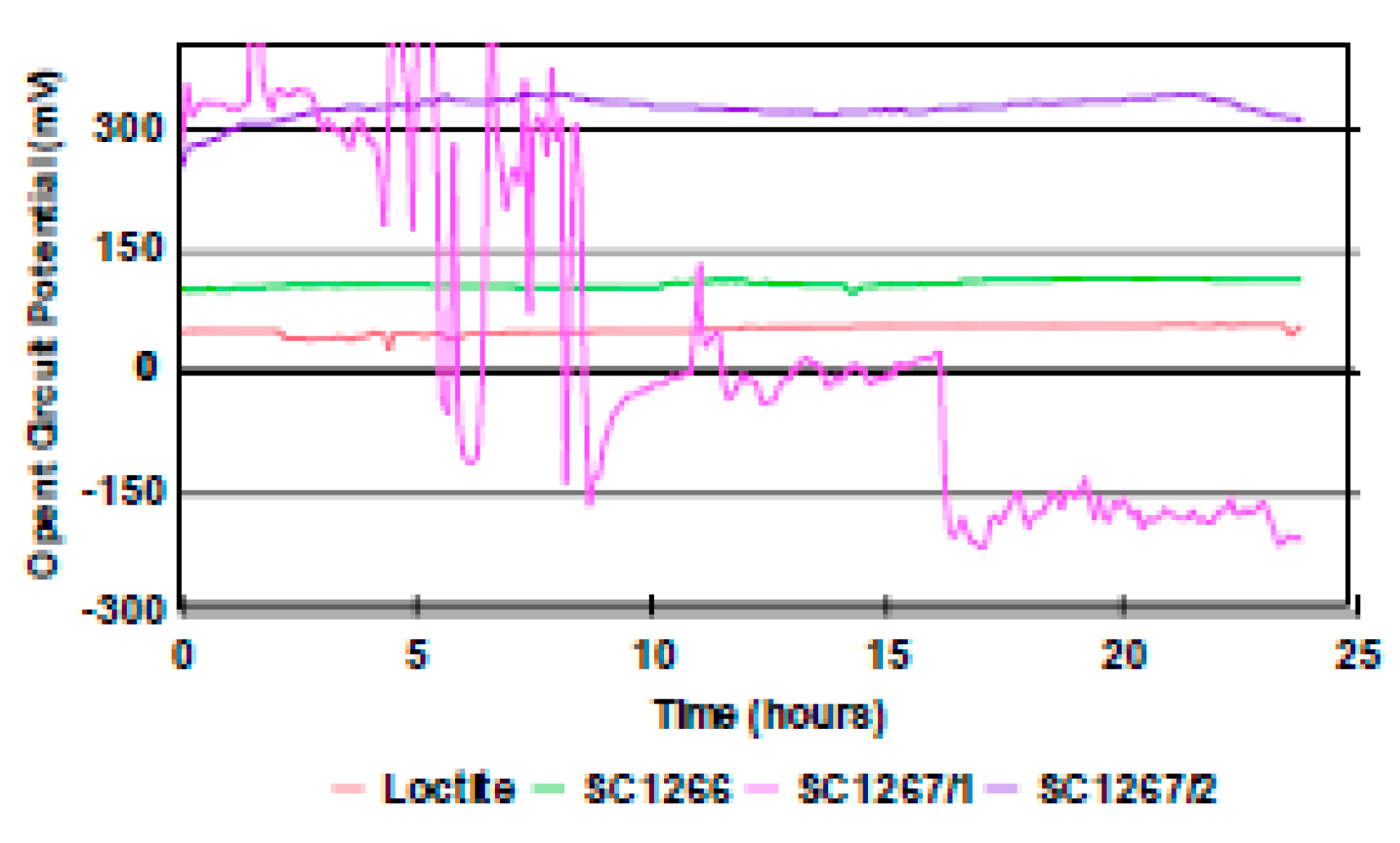

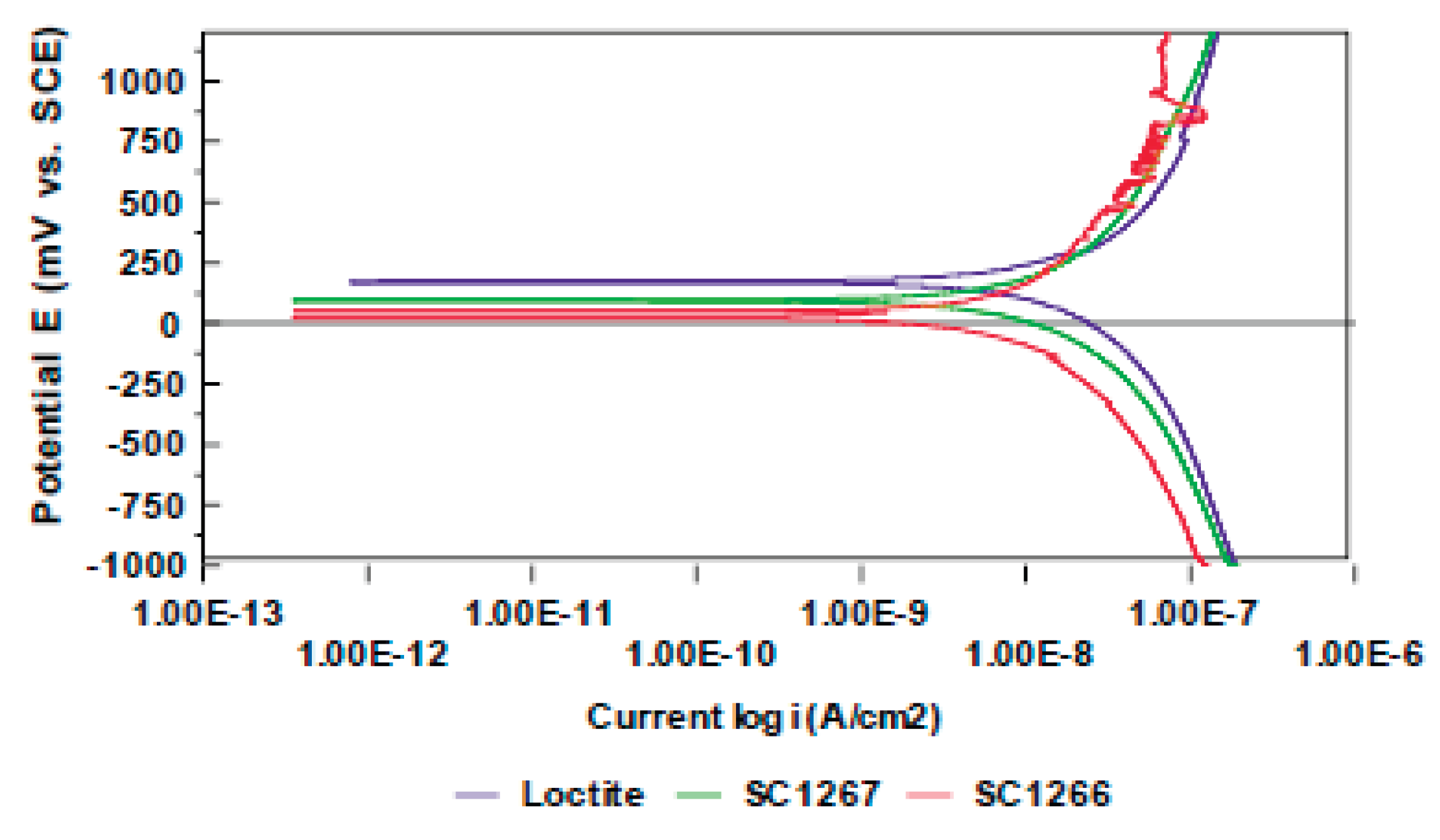

3.1. Electrochemical Techniques:

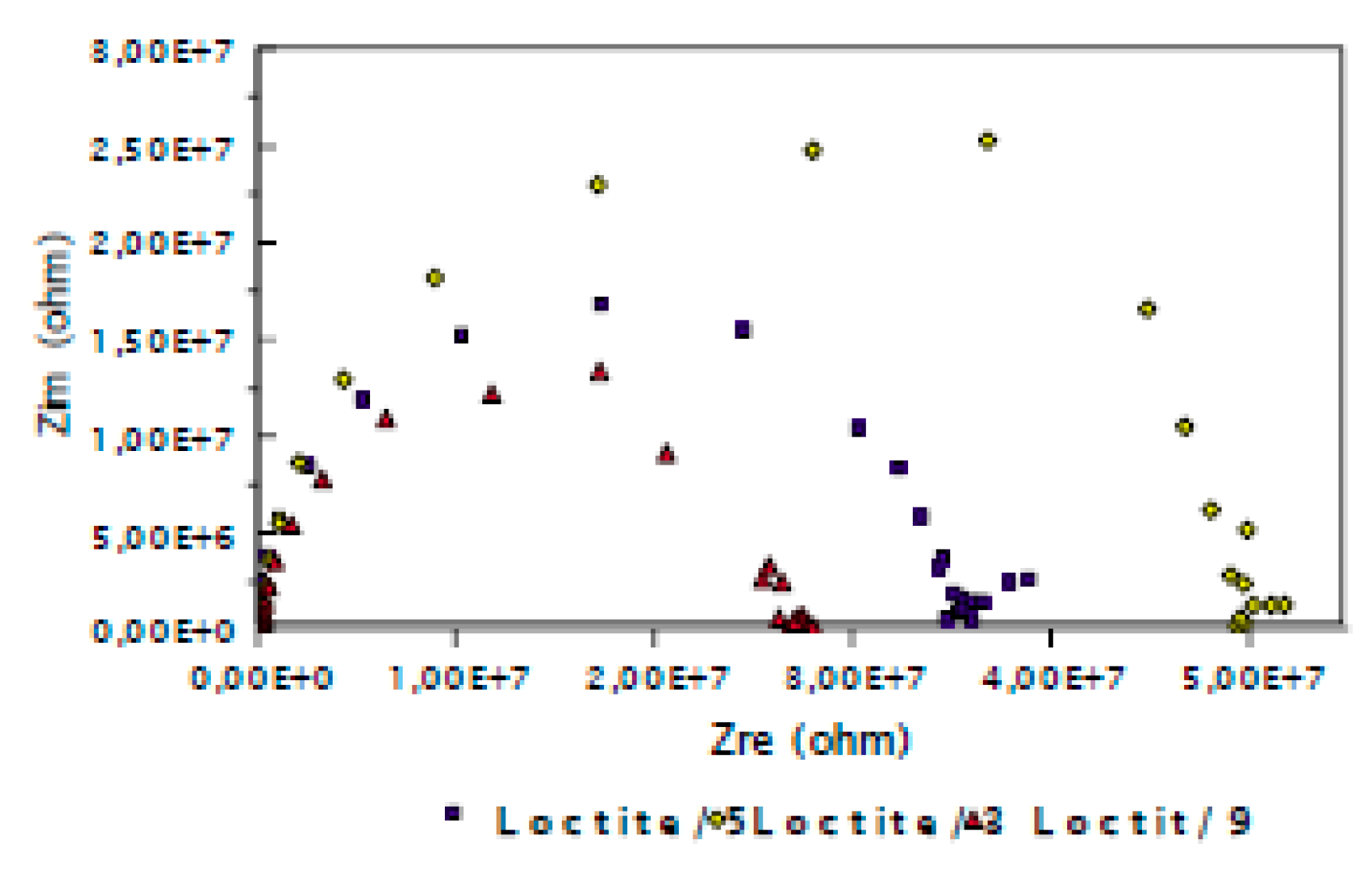

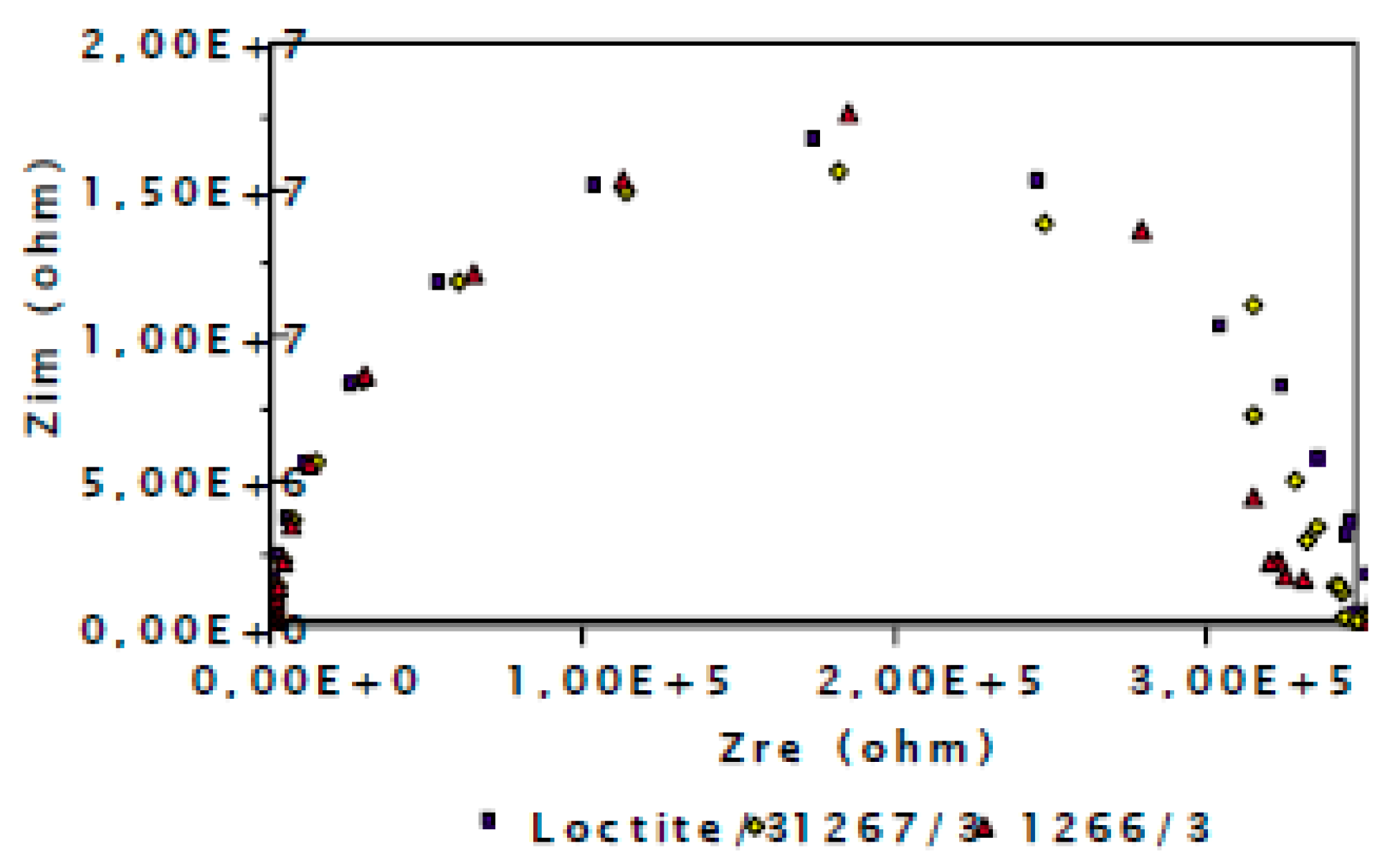

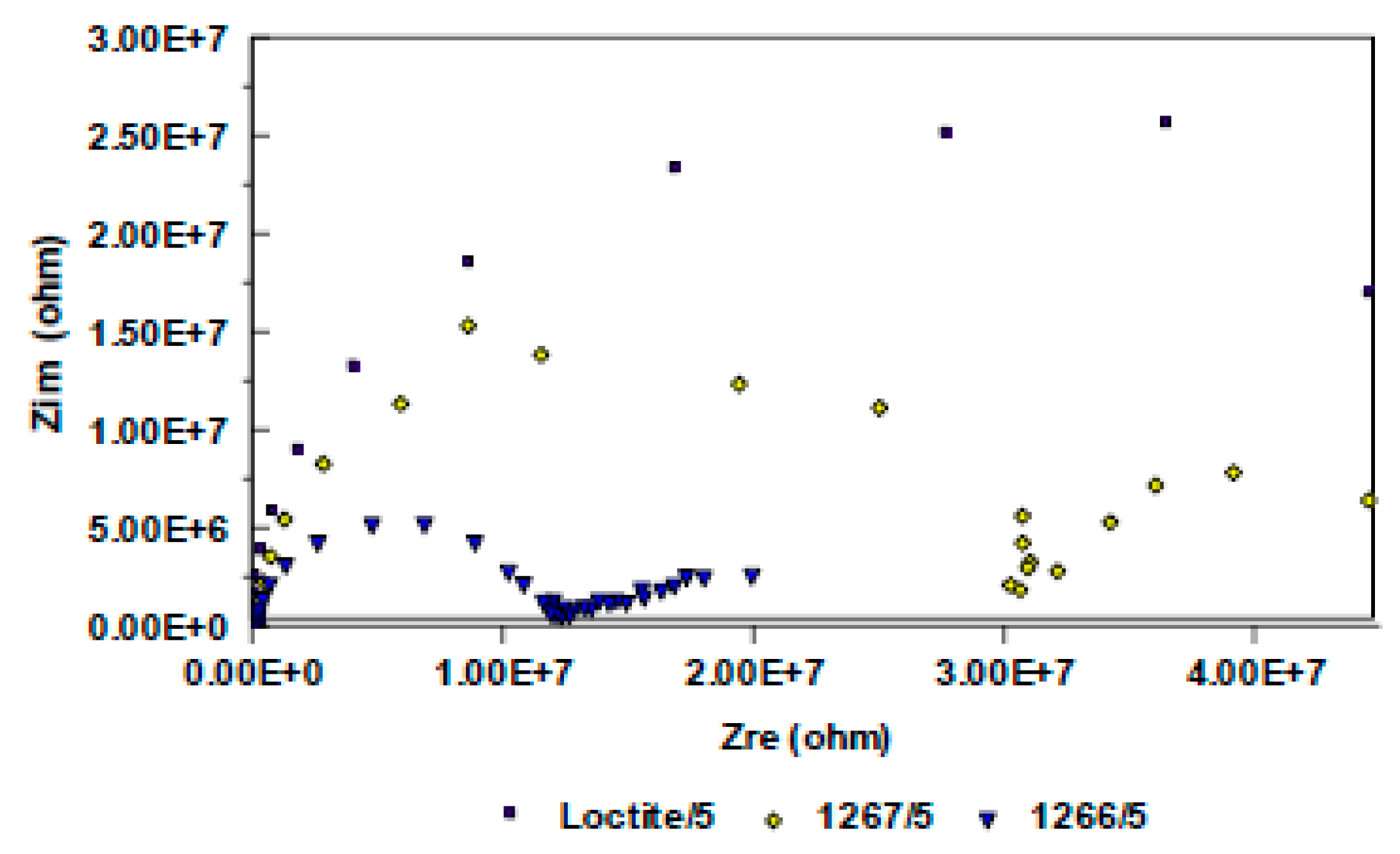

3.2. Evaluation of the Corrosion by Measuring the Impedance.

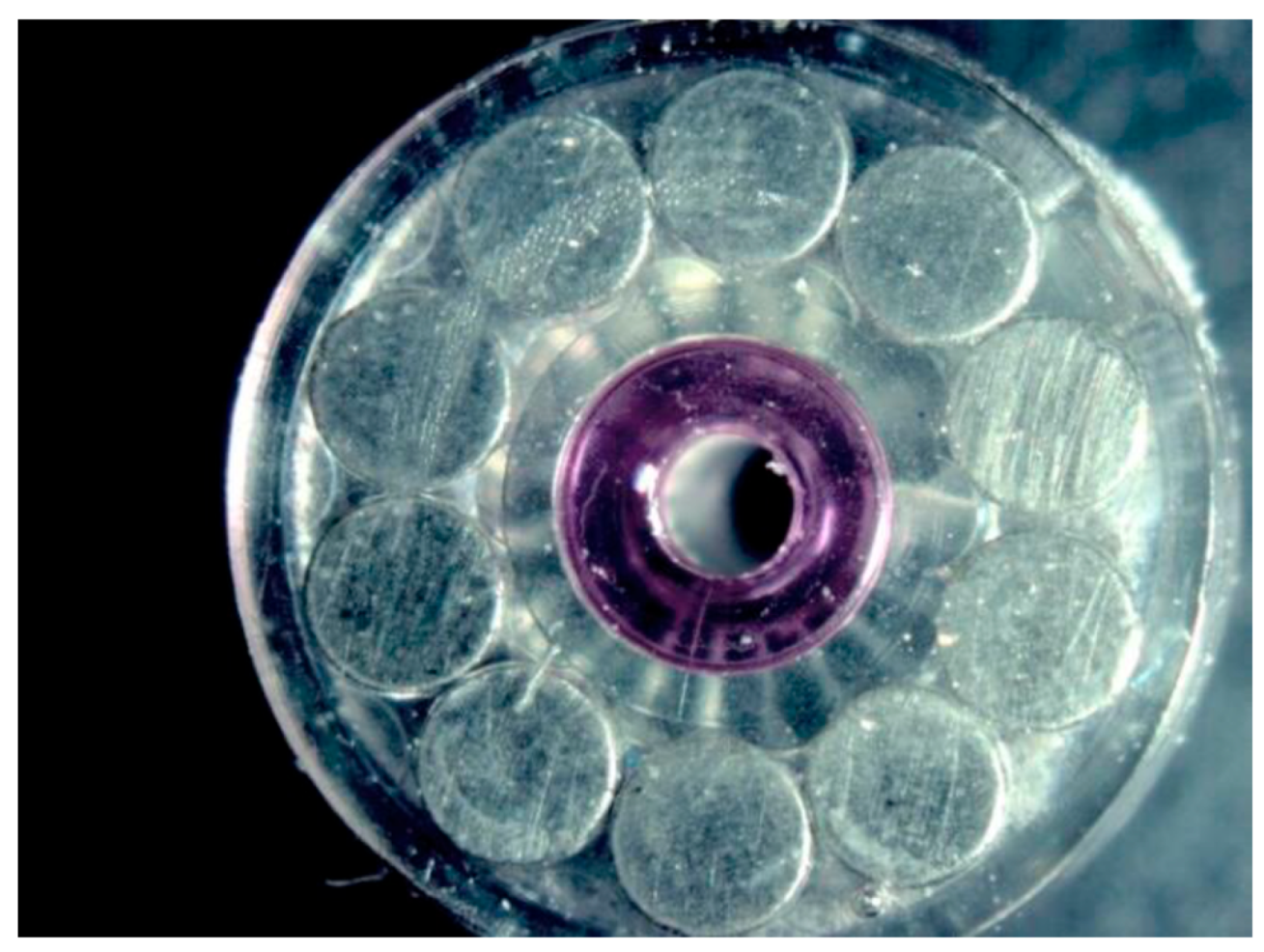

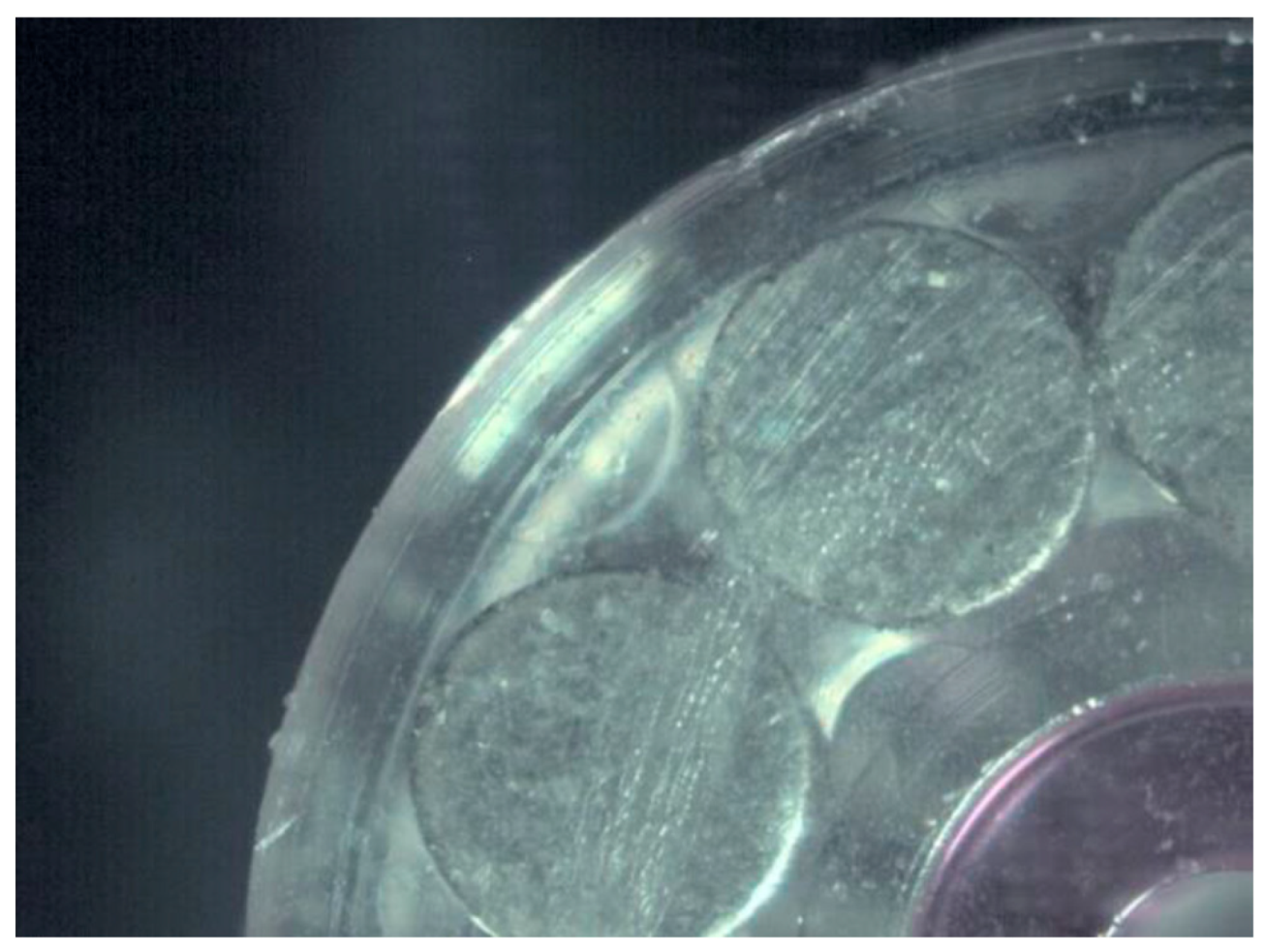

3.3. Evalutaion Corrosion According to the Nielsen-Tuccillo Method

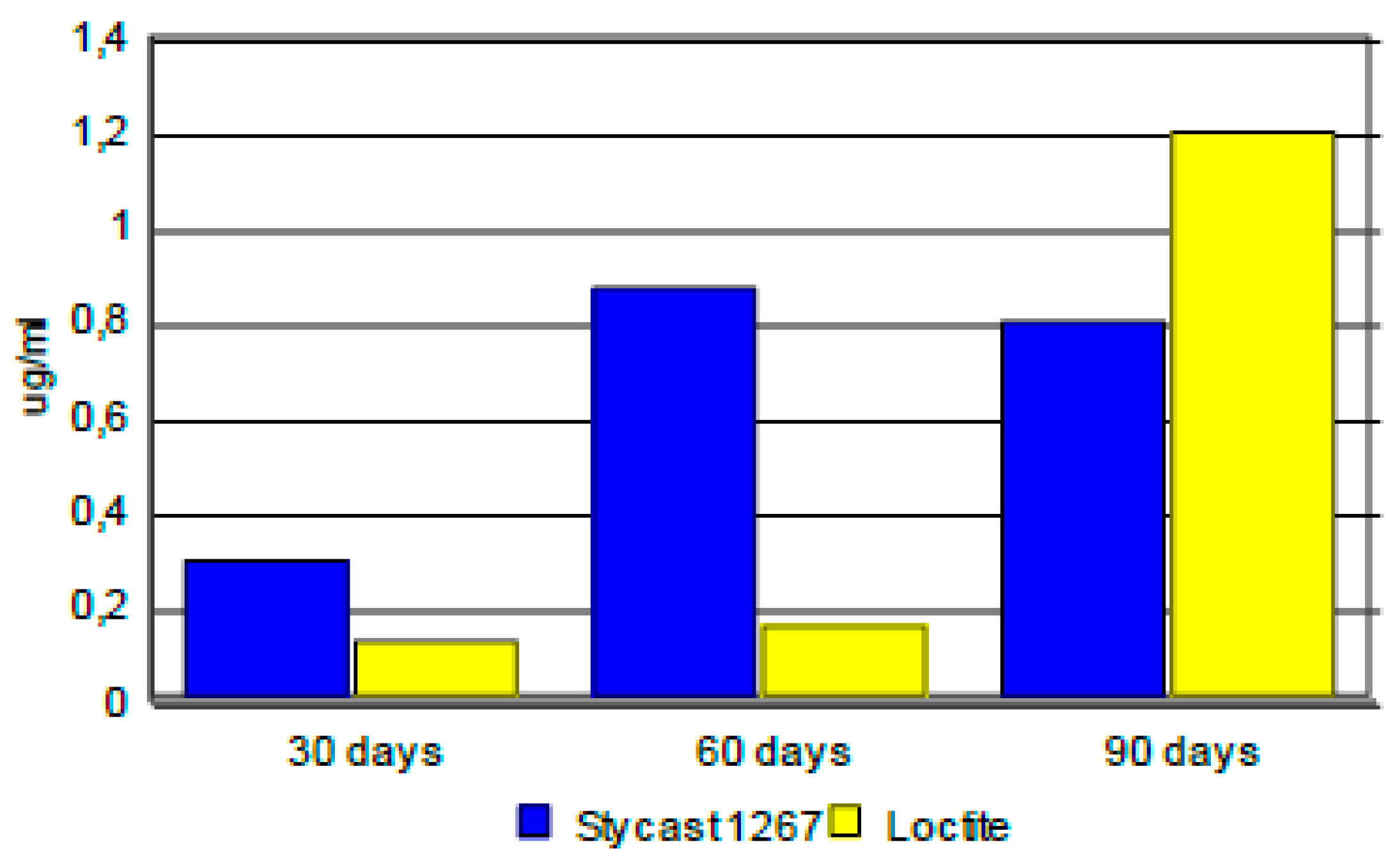

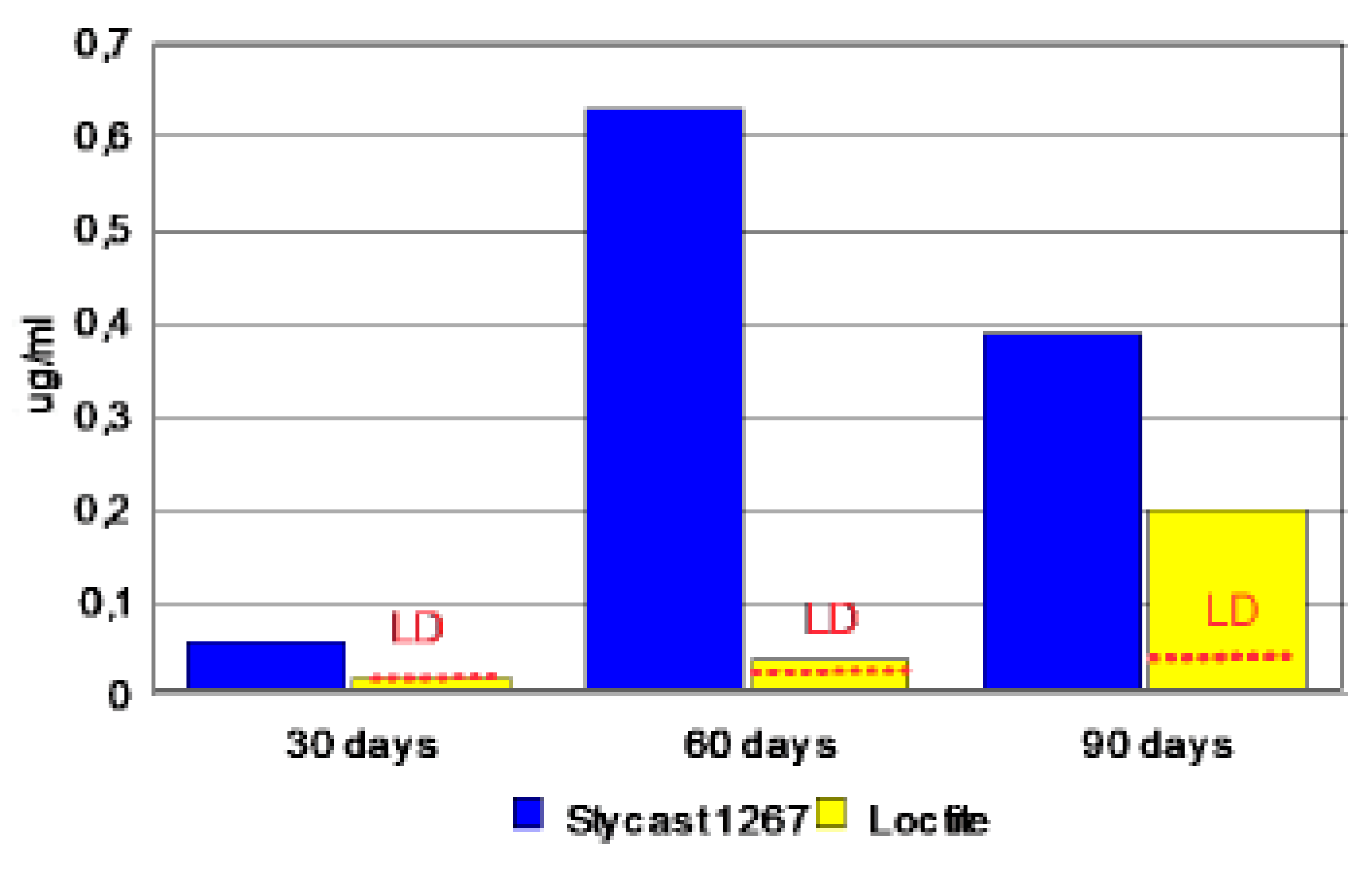

3.4. Kinetics of Release on Encapsulated Magnets.

| Duration | Samples | Borium | Cobalt | Nyodymium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [μg.l-1] | [μg.l-1] | [μg.l-1] | ||

| Blank | < 1 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | |

| 30 days | Blank 1 | < 1 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 |

| Stycast 1267 | 1.30 | 0.30 | 0.06 | |

| Loctite | < 1 | 0.13 | < 0.02 | |

| Blank | < 2 | < 0.04 | < 0.04 | |

| 60 days | Blank 1 | < 2 | < 0.04 | < 0.04 |

| Stycast 1267 | < 2 | 0.87 | 0.63 | |

| Loctite | < 2 | 0.16 | < 0.04 | |

| Blank | 29 | < 0.2 | < 0.2 | |

| 90 days | Blank 1 | 8.02 | < 0.2 | < 0.2 |

| Stycast 1267 | 8.31 | 0.80 | 0.39 | |

| Loctite | 22 | 1.2 | < 0.2 |

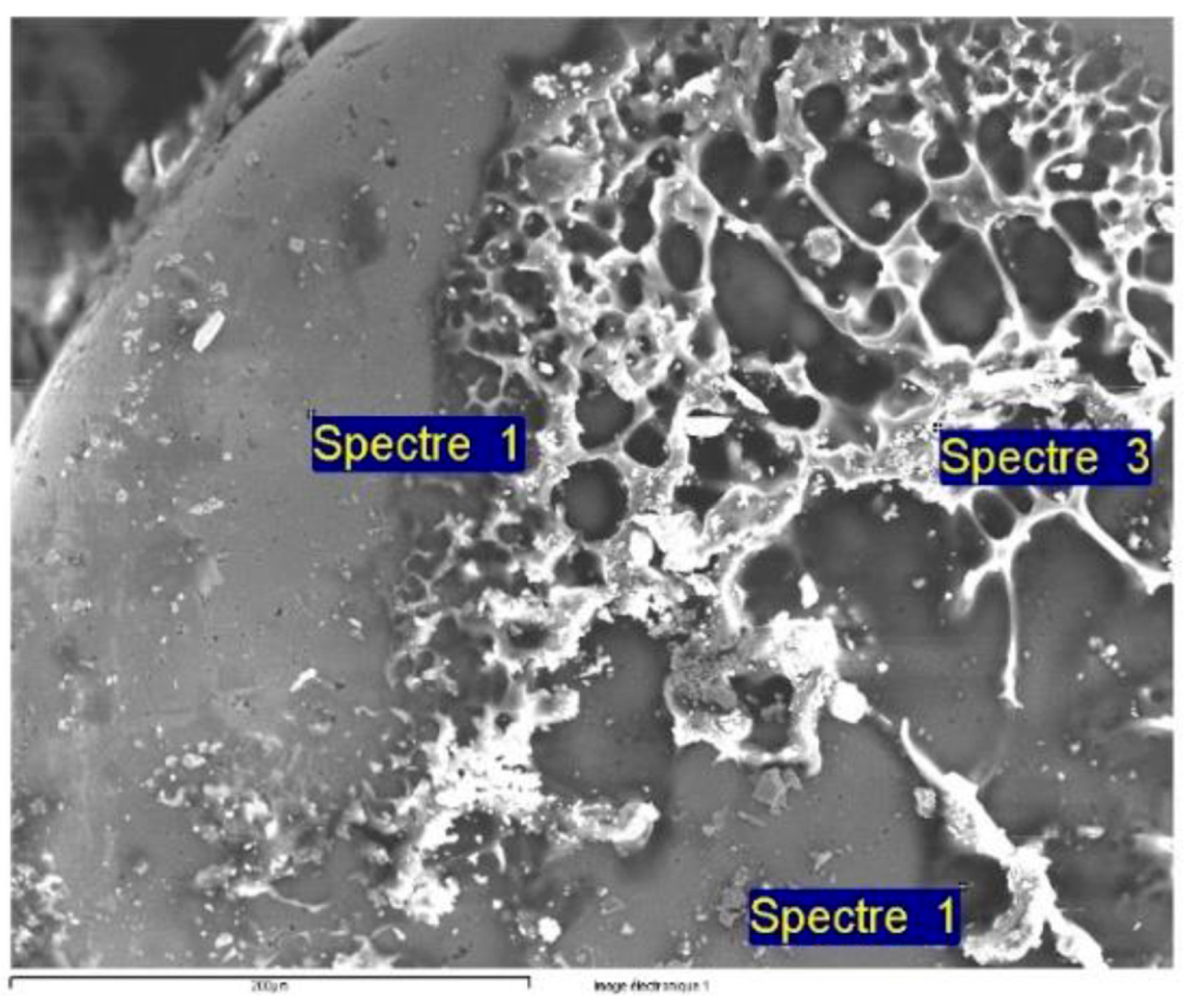

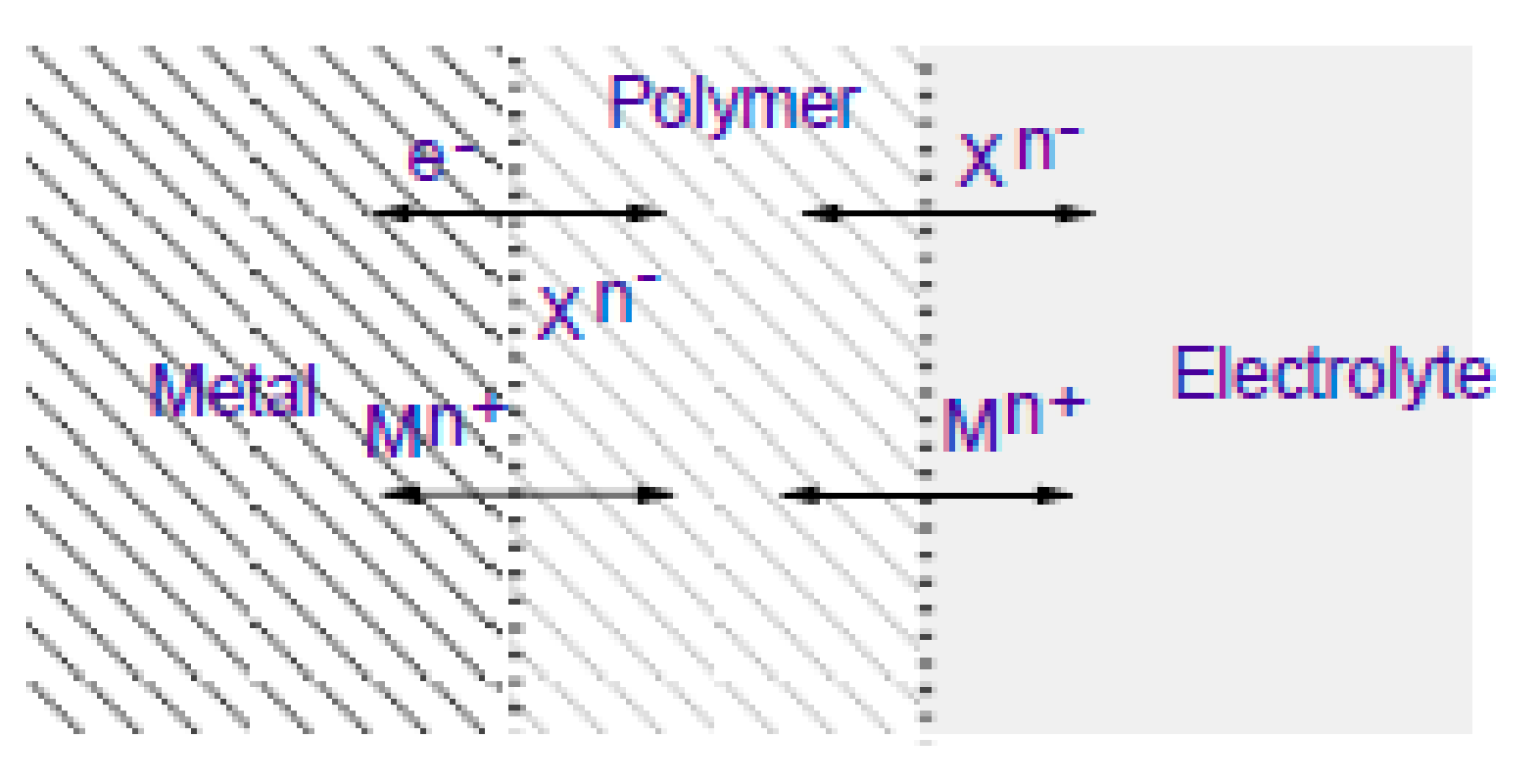

3.5. Theoretical Considerations

| Spectrum | C | O | Na | Si | Cl | Co | Sm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrum 1 | 5.88 | 1.58 | 1.07 | 62.94 | 28.53 | ||

| Spectrum 1 | 17.56 | 0.90 | 49.91 | 31.63 | |||

| Spectrum 3 | 72.24 | 17.11 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 7.12 | 3.13 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Rekate, H.L. A consensus on the classification of hydrocephalus: its utility in the assessment of abnormalities of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011, 27(10):1535-41. [CrossRef]

- Kahle, K.T., Kulkarni, A.V., Limbrick, D.D., Warf, B.C. (2016). Hydrocephalus in children. The Lancet, 2016, 387(10020), 788–799. [CrossRef]

- Faheem Anwar, Kuo Zhang, Changcheng Sun, Meijun Pang, Wanqi Zhou, Haodong Li, Runnan He, Xiuyun Liu, Dong Ming. Hydrocephalus: An update on latest progress in pathophysiological and therapeutic research. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2024, Vol 181, 117702. [CrossRef]

- Drake, J.M., Kestle, J.R.W., Tuli, S. (2000). CSF shunts 50 years on – past, present and future. Child’s Nervous System, 2000 , 16(10–11), 800–804. [CrossRef]

- Min Li , Han Wang, Yetong Ouyang , Min Yin , Xiaoping Yin. Efficacy and safety of programmable shunt valves for hydrocephalus: A meta-analysis. Int J Surg . 2017, 44:139-146. [CrossRef]

- Kuan-Hung Chen, Peng-Wei Hsu, Bo-Chang Wu, Po-Hsun Tu, Yu-Chi Wang, Cheng-Chi Lee1, Yin-Cheng Huang, Ching-Chang Chen, Chi-Cheng Chuang, Zhuo-Hao Liu1, Long-term follow-up and comparison of programmable and non-programmable ventricular cerebrospinal fluid shunts among adult patients with different hydrocephalus etiologies: a retrospective cohort study. Acta Neurochirurgica, (Wien). Vol 165, pages 2551–2560, (2023). [CrossRef]

- 7. H Xu, Z X Wang, F Liu, G W Tan, H W Zhu, D H Chen. Programmable shunt valves for the treatment of hydrocephalus: a systematic review Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2013, 17(5):454-61. [CrossRef]

- Pudenz, R.H., & Foltz, E.L. Hydrocephalus: overdrainage by ventricular shunts. A review and recommendations. Surg Neurol. 1991, 35(3), 200-12. [CrossRef]

- F Eymen Ucisik , Alexander B Simonetta, Eliana M Bonfante-Mejia. Magnetic resonance imaging-related programmable ventriculoperitoneal shunt valve setting changes occur often, Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2022, 164(2):495-498. [CrossRef]

- Aswin Chari, B.M. B.Ch., Marek Czosnyka, M. , Richards, H.K., Pickard, J.D., Chir. M., Czosnyka, Z.H. Hydrocephalus shunt technology: 20 years of experience from the Cambridge Shunt Evaluation Laboratory. Neurosurgery ,2014, Vol, 120: Issue 3, 697–707. [CrossRef]

- Takashi Inoue , Yasutaka Kuzu, Kuniaki Ogasawara, Akira Ogawa. Effect of 3-tesla magnetic resonance imaging on various pressure programmable shunt valves. J Neurosurg. 2005, 103(2 Suppl):163-5. [CrossRef]

- Arnell K, Eriksson E, Olsen L (2006) The programmable adult Codman Hakim valve is useful even in very small children with hydrocephalus. A 7-year retrospective study with special focus on cost/benefit analysis. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2006 16(1):1–7. [CrossRef]

- Certas™ Programmable Valve System – Technical White Paper. Codman & Shurtleff Inc. https://products.integralife.com/file/general/1549983654.pdf.

- Chen, B. , Dammann, P., Jabbarli, R., Sure, U., Quick, H.H., Kraff ,O., Karsten H Wrede, K.H. Safety and function of programmable ventriculo-peritoneal shunt valves: An in vitro 7 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging study, PLoS One. 2023 11;18(10):e0292666. [CrossRef]

- M Akbar, A Aschoff, J C Georgi, E Nennig, S Heiland, R Abel, C Stippich. Adjustable cerebrospinal fluid shunt valves in 3.0-Tesla MRI: a phantom study using explanted devices. Rofo . 2010 Jul;182(7):594-602. [CrossRef]

- König,R.E., Stucht ,D., Baecke, S., Rashidi , A., Speck ,O., Sandalcioglu , I.E., Luchtmann, M. Pase-Contrast MRI Detection of Ventricular Shunt CSF Flow: Proof of Principle. J Neuroimaging. 2020, 30(6):746-753. [CrossRef]

- Flürenbrock F., Leonie Korn L., Dominik Schulte, D., Podgoršak ,A., Chomarat ,J., Hug ,J., Hungerland ,T., Holzer, C , Iselin ,D., Luca Krebs, L., Rosina Weiss,R., Oertel,M.F., Stieglitz,L., Weisskopf, M., Mirko Meboldt,M., Melanie N Zeilinger,M. Daners , M. VIEshunt: towards a ventricular intelligent and electromechanical shunt for hydrocephalus therapy. Fluids Barriers CNS . 2025, 14;22(1):28. [CrossRef]

- Rrinivas Dwarakanath, Gaurav Tyagi, Gyani J S Birua, Shunt Implants – Past, Present and Future. Neurology India 2021 69(8):449-456. [CrossRef]

- Richard, J.E. , Drak, J. Cerebrospinal Fluid Devices, CHAPTER 192, Programmable Valves. https://clinicalgate.com/cerebrospinal-fluid-devices.

- LOCTITE-STYCAST-1266-en_GL.pdf. https://www.mouser.com/datasheet/2/773/LOCTITE_STYCAST_1266_en_GL-3434542.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOorHdnAHeKy-KdReNhIW1czupOK-Qm5-K023_9i9Up-AHSH09Y_x.

- LOCTITE_STYCAST_1267_en_US_9445.pdf. https://shop.bm-chemie.com/media/akeneo_connector/media_files/L/O/LOCTITE_STYCAST_1267_en_US_9445.pdf.

- 1382876-LT-8251_IA Medical Brochure_v12.indd. Loctite Adhesives for Medical Devices https://eu.mouser.com/pdfDocs/medical-product-selector-guide-adhesives-for-medical-device-assembly.pdf.

- Gutfleisch,O. J., Müller,L. K-H., Schul, L. FePt Hard Magnets. Advanced Eng Mat 2005, 7, no 4.

- ASTM G106-89(1999) - Standard Practice for Verification of Algorithm and Equipment for Electrochemical Impedance Measurements.

- Wenyu Wang, Yanfang Yang, Donglei Wang, Lihua Huang, Toxic Effects of Rare Earth Elements on Human Health: A Review. Toxics 2024, 12(5), 317. [CrossRef]

- Nemi Malhotra, Hua-Shu Hsu, Sung-Tzu Liang, Marri Jmelou M Roldan, Jiann-Shing Lee , Tzong-Rong Ger, Chung-Der Hsiao. An Updated Review of Toxicity Effect of the Rare Earth Elements (REEs). Aquatic Organisms, Animals (Basel) 2020, 16;10(9):1663. [CrossRef]

- Yan Liu, Ruxia Pu, Bo Zou, Xiaojia Zhang, Xiaohui Wang, Haijing Yin, Jing Jin, Yabin Xie, Yuting Sun, Xiaoe Jia, Yannan Bi. Samarium Oxide Exposure Induces Toxicity and Cardiotoxicity in Zebrafish Embryos Through Apoptosis Pathway Appl Toxicol 2025,45(7).1258-1269. [CrossRef]

- Boyu Yang, Luning Sun, Zheng Peng , Qing Zhang , Mei Lin , Zhilin Peng, Jue Yang , Lan Zheng5 Toxicity of rare earth elements europium and samarium on zebrafish development and locomotor performance J Hazard Mater. 2025, 5:487:137213. [CrossRef]

- Hun Yee Tan1, Yin How Wong, Azahari Kasbollah, Mohammad Nazri Md Shah, Basri Johan Jeet Abdullah5, Alan Christopher Perkins, Chai Hong Yeong7 Biodistribution and long-term toxicity of neutron-activated Samarium-153 oxide-loaded polystyrene microspheres in healthy rats Nucl Med Biol. 2025, 146-147:109026. [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, A., Chiba, M., Kumasaka, T. Behavior of samarium inhaled by mice: Exposure length and time-dependent change Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry Vol 281,2009 pages 119–122. [CrossRef]

- Bondemark ,L., ,Kurol, J., Wennberg, A. Orthodontic rare earth magnet--in vitro assessment of cytotoxicity Br J Orthod. 1994, 21(4):335-41. [CrossRef]

- Donohue, VE, McDonald F., Evans, R. In vitro cytotoxicity testing of neodymium-iron-boron magnets. J Appl Biomater. 1995 Spring;6(1):69-74. [CrossRef]

- Slaymaker,J. , Rossouw,E., Michelogiannakis, D. The influence of protective coatings on corrosion resistance in orthodontic magnets: A systematic review of in vitro studies. Int Orthod. 2025 8;24(1):101080. [CrossRef]

- Noar , J.H., Evans. R.D. Rare earth magnets in orthodontics: an overview. Br J Orthod 1999, 26(1):29-37. [CrossRef]

- Darendeliler , M.A., Darendeliler, A., Mandurino, M.. Clinical application of magnets in orthodontics and biological implications: a review. Eur J Orthod. 1997 , 19(4):431-42. [CrossRef]

- C. Wagner, C., Traud, W. “On the Interpretation of Corrosion Processes through the Superposition of Electrochemical Partial Processes and on the Potential of Mixed Electrodes,” with a Perspective by F. Mansfeld. CORROSION 2006, 62(10). [CrossRef]

- Thorsten Eichler Corrosion Books: Electrochemical Noise Measurement for Corrosion Applications. By: J.R. Kearns, J.R. Scully, P.R. Roberge, D.L. Reichert, J.L. Dawson Materials and Corrosion, 2007 58(5): 390-390. [CrossRef]

- Da-Hai Xia, Shizhe Song, Yashar Behnamian, Wenbin Hu,1 Y. Frank Cheng Jing-Li Luo, and François Huet. Review—Electrochemical Noise Applied in Corrosion Science: Theoretical and Mathematical Models towards Quantitative Analysis. Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 2020, 167 081507. [CrossRef]

- Florian Mansfeld. The Electrochemical Noise Technique - Applications in Corrosion Research. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2005 Volume 780, Issue 1. [CrossRef]

- Trentin A, Pakseresht A, Duran A, Castro Y, Dušan, G. Electrochemical Characterization of Polymeric Coatings for Corrosion Protection: A Review of Advances and Perspectives. Polymers 2022, 14(12), 2306; [CrossRef]

- Lazanas. A. Ch., Prodromidis.M. I., Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy─A Tutorial. CS Measurement Science Au 2023, Vol 3/Issue 3. [CrossRef]

- Saikia M, Dutta T, Jadhv N, Lalita D.J, Insights into the Development of Corrosion Protection Coatings Polymers 2025, 17(11), 1548; [CrossRef]

- Yosra K. Christopher M. Serfass A. Cagnard, K.R. Houston S. A. Khan, Lilian C. H, Orlin D. V, Molecular structure effects on the mechanisms of corrosion protection of model epoxy coatings on metals. Materials Chemistry Frontiers, 2023, 7, 274-286 . [CrossRef]

- Samardžija M , Alar V, Špada V, Stojanović I. Corrosion Behaviour of an Epoxy Resin Reinforced with Aluminium Nanoparticles. Coatings 2022, 12(10), 1500; [CrossRef]

- Henkel Corporation, Stycast and Loctite Epoxy Resins Technical Datasheets, 2023. https://datasheets.tdx.henkel.com/LOCTITE-STYCAST-1090-SI-CAT-23LV-en_GL.pdf.

- Mosas A. K. A, Chandrasekar, A.R, Dasan A, Pakseresht A, Galusek D. Recent Advancements in Materials and Coatings for Biomedical Implants. Gels 2022, 8(5), 323; [CrossRef]

- Muhammad A. N. S., Farooq A., Lodhi M. J. K., Deen K. — Performance Evaluation of Epoxy Coatings Containing Different Fillers in Natural and Simulated Environmental Conditions for Corrosion Resistance. Op Acc J Bio Eng & Bio Sci. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad A. N. S., Farooq A., Lodhi M. J. K., Deen K. Performance Evaluation of Epoxy Coatings Containing Different Fillers in Natural and Simulated Environmental Conditions for Corrosion Resistance. Op Acc J Bio Eng & Bio Sci. 2019. DOI : 10.32474/OAJBEB.2019.03.000168.

| Surface treatment | Corrosion potential E(i=0) (mV) |

Polarization resistance Rp (MOhms /cm2) |

Corrosion current density icorr (nA/cm2) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loctite | after 3 days after 5 days after 9 days |

182.5 215.6 155.0 |

102.6 67.0 32.47 |

1.7 2.6 5.4 |

| Stycast 1267 | after 3 days after 5 days |

187.7 172.0 |

67.4 41.3 |

2.6 4.2 |

| StyCast 1266 | after 3 days after 5 days |

209.1 169.5 |

59.43 39.9 |

2.9 4.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).