Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Spaces

2.1. Schwartz—Type Spaces

2.2. Zemanian-Type Spaces

3. The Quasiasymptotic Behavior

4. Kernels

5. The Fractional Fourier Transform

6. The Fractional Fourier Cosine (Sine) Transform

7. The Short-Time Fractional Fourier Transform

8. The Fractional Stockwell Transform

9. The Fractional Wavelet Transform

10. The Fractional Hankel transform

| Transform | Kernel Base | Domain | Fractional Parameter Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| FRFT | Exponential (Fourier) | Time–Frequency | Rotation in time–frequency plane |

| FRWT | Scaled wavelets | Time–Scale | Fractional modulation and dilation |

| FRSTFT | Exponential + window | Time–Frequency | Local fractional analysis |

| FRST | Localized exponential | Time–Frequency | Fractional phase rotation |

| FRHT | Bessel-based | Radial domain | Fractional rotation in spatial–frequency plane |

| Transform | Connection |

|---|---|

| FRFT and FT | |

| STFRFT and FT | |

| FRST and FT | |

| STFRFT and STFT | |

| FRCFT and FCT | |

| FRSFT and FST | |

| FRST and FRWT | |

| FRHT and HT |

11. Applications of Fractional Transforms

11.1. The Fractional Fourier Transform

11.2. The Fractional Stockwell Transforms

11.3. The Fractional Wavelet Transforms

11.4. The Fractional Hankel Transforms

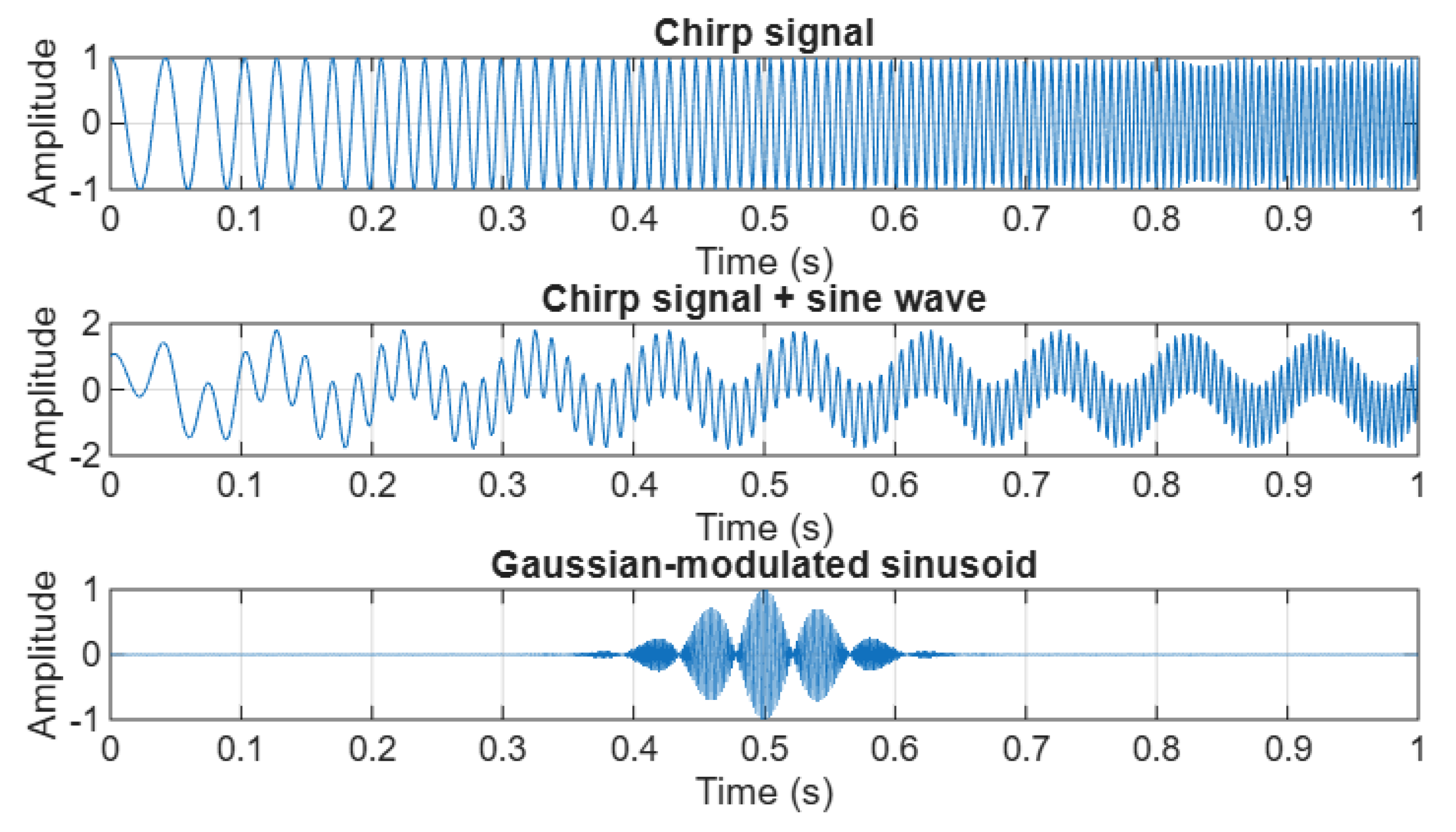

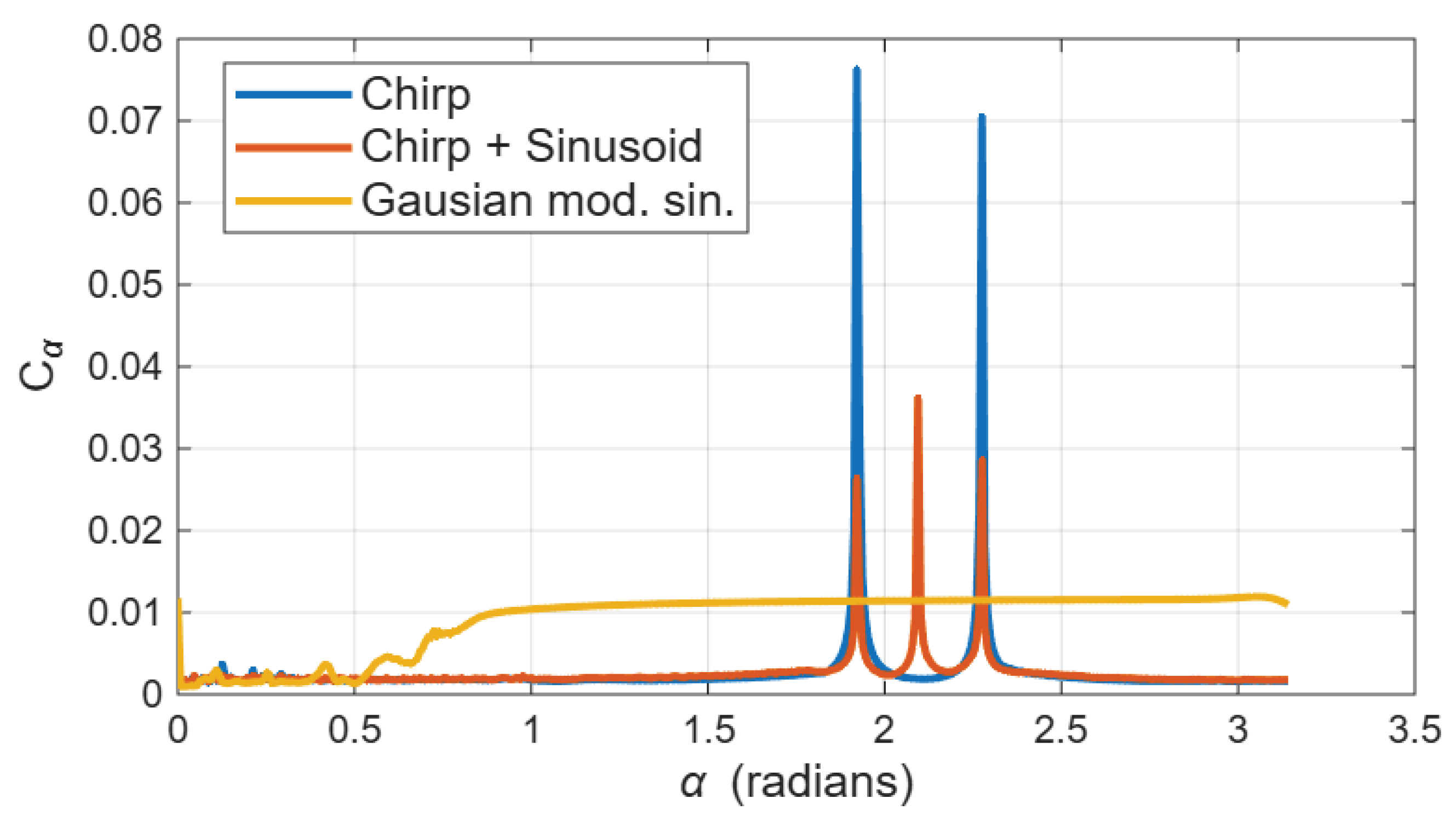

11.5. Application Example

References

- Bochner, K. Chandrasekharan, Fourier Transforms, Princeton University Press., 1949.

- Bracewell, R. N. , The Fourier Transform and Its Applications ,3rd ed., Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

- Capus, C.; Brown, K., Short-time fractional Fourier methods for the time-frequency representation of chirp signals, J. Acoust. Soc. Amer., 2003, 113(6), 3253–-3263. [CrossRef]

- Gröchenig, K., Foundations of time-frequancy analysis, Birkhauser Boston, Inc., Boston, MA, 2001.

- Chui, C.K., An Introduction to Wavelets, San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1992.

- Meyer, Y. Yves, Wavelets and Operators, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Stockwell, R.G.; Mansinha, L.; Lowe, RP., Localization of the complex spectrum: The S transform, IEEE Trans Signal Process, 1996, 44, 998–-1001.

- Namias, V., Fractionalization of Hankel transform. J. Inst. Math. Appl., 1980, 26, 187–197.

- Namias, V., The fractional order Fourier transform and its application to quantum mechanics, J. Inst. math. Appl., 1980, 25, 241–265. [CrossRef]

- Ozaktas, H. M.; Kutay, M. A.; and Mendlovic, D., Introduction to the Fractional Fourier Transform and Its Applications, Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics, 1999, 106, 239–286.

- Ran Tao; Yan-Lei Li; Yue Wang, Short-Time Fractional Fourier Transform and Its Applications, IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 2010, 58(5), 2568–2580. [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, A.W.; Mendlovic, D.; Zalevsky Z.; Dorsch R.G., Some Important Fractional for Signal Processing, Optics Communications, 1996 125(1-3), 18–20.

- Alieva, T; Bastiaans M. J., Fractional cosine and sine transforms in relation to the fractional Fourier and Hartley transforms, Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on Signal Processing and Its Applications, Paris, France, 2023, 2003(1), 561–564.

- Hudzik H.;, Jain, P.; Kumar R., On generalized fractional cosine and sine transforms, Georgian Mathematical Journal, 2018, 25(2), 259–270. [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.C.; Yeh M.H., The discrete fractional cosine and sine transforms, IEEE Transaction on Signal Processing, 2002, 49(6), 1198–1207.

- Ping, XD; Guo, K., Fractional S-transform—Part 1, Theory. Applied Geophysics, 2012, 9(1), 73-–79.

- Betancor J.J., On Hankel transformable distribution spaces, Publications de L’institut mathematique, 1999, 65(79), 123–141.

- Betancor J.J. and Rodriquez-Mesa L., Hankel convolution on distributions spaces with exponential growth, Studia Mathematica, 1996, 121(1), 35–52.

- Bingham N. H., A Tauberian theorem for integral transforms of Hankel type,J. London Math. Soc., 1972, 2, 5–6. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, C.J.R.; Larkin, K.G., Similarity theorems for fractional Fourier transforms and fractional Hankel transforms. Opt. Commun., 1998, 154, 173–178. [CrossRef]

- Zemanian, A.H., Generalized Integral Transformations. Interscience Publishers, New York, 1968.

- Zemanian, A.H., A distributional Hankel transformation, SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1966, 14, 561–576.

- Zemanian, A.H., The Hankel transformation of certain distributions of rapid growth,SIAM J. Appl. Math., 1966, 14, 678–690. [CrossRef]

- Zemanian, A.H., Some Abelian Theorems for the Distributional Hankel and K Transformations, SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics, 1966, 14(6), 1255–1265.

- Zemanian, A.H., Distribution theory and Transform Analysis, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1965.

- Atanasova, S.; Maksimović, S.; Pilipović, S., Abelian and Tauberian results for the fractional Fourier and short time Fourier transforms of distributions, Integral transform and Special functions, 2024, 35 (1), 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz L. Thory des Distributions I., 2nd ed. Paris: Hermann; 1957.

- Milton, E.O., Fourier transforms of odd and even tempered distributions, Pacific Journal of Mathematics, 1974, 50(2), 563–572. [CrossRef]

- Holschneider, M., Wavelets. An analysis tool. New York: The Clarendon Press. Oxford University Press; 1995.

- Pathak, RS., The wavelet transform of distributions, Tohoku Math. J. 2004, 56, 411–421.

- Prasad, A.; Singh, V.K., The fractional Hankel transform of certain tempered distributions and pseudo-differential operators. Ann Univ Ferrara, 2013, 59, 141–158. [CrossRef]

- Estrada, R.; Kanwal, R. P., A distributional approach to asymptotics. Theory and applications, Second edition, Birkhäuser, Boston, 2002.

- Misra, O. P.; Lavoine, J. L., Transform analysis of generalized functions, North-Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam, 1986.

- Atanasova, S.; Jakšić, S.; Maksimović, S.; Pilipović, S. (2025). Abelian and Tauberian results for the fractional Hankel transform of generalized functions. Integral Transforms and Special Functions, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Atanasova S.; Jakšić S.; Maksimović S.; Pilipović S., Abelian and Tauberian results for the fractional Hankel transform in Zemanian-type spaces, preprint (https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.20614).

- Maksimović, S.; Atanasova, S.; Mitrovic, Z., Abelian and Tauberian results for the fractional Fourier cosine (sine) transform. AIMS Mathematics, 2024, 9 (5), 12225–12238. [CrossRef]

- Vladimirov, V. S.; Drozhzhinov, Yu. N.; Zavialov, B. I., Tauberian theorems for generalized functions, Kluwer Academic Publishers Group, Dordrecht, 1988.

- Maksimović S., Asymptotic results for the distributional fractional Stockwell and fractional wavelet transforms, preprint.

- Pilipović, S.; Stanković, B.; Takači, A., Asymptotic Behavior and Stieltjes Transformation of Distribution, Taubner-Texte zur Mathematik, band 116, 1990.

- Almeida L.B., The Fractional Fourier Transform and Time-Frequency Representations , IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 1994, 42 (11), 3084–3091. [CrossRef]

- Catherall, A. T.; Williams, D. P., Detecting non-stationary signals using fractional Fourier methods, [Online]. Available: http://www. ima.org.uk/Conferences/mathssignalprocessing2006/williams.pdf.

- Kerr, F. H., A distributional approach to Namias’ fractional Fourier transforms, Proc. Roy. Soc. Edinburgh Sect. A 108, (1988), 133–143. [CrossRef]

- Stanković L.; Alieva T.; Bastiaans M. J., Time–frequency signal analysis based on the windowed fractional Fourier transform, Signal Processing, 2003, 83(11), 2459–2468. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Bi, G.; Chen, Y. Q., Chip signal analysis by using adaptive short-time fractional Fourier transform, 2000 [Online]. Available:http://www.eurasip.org/Proceedings/Eusipco/Eusipco2000/sessions/ WedPm/OR3/cr1282.pdf.

- Chen W,; Fu, Z. W.; Grafakos, L.; Wu, Y, Fractional Fourier transforms on Lp and applications. Appl Comput Harmon Anal, 2021, 55, 71–-96.

- McBride A.C.; Kerr F. H., On Namias’s fractional Fourier transforms, IMA J. Appl. Math., 1987 39, 159-–175.

- Pathak R.S.; Prasad A.; Kumar M., Fractional Fourier transform of tempered distributions and generalized pseudo/differential operator, J. Pseudo-Differ. Oper. Appl, 2012, 3, 239–254. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., Fractional Fourier transform of a class of boehmians, International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics, 2015, 101(3), 413–420.

- Zayed A.I., Fractional Fourier transform of generalized functions, Integ. Trans. Spl. Funct., 1998, 7, 299–312. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Kumar, M. Product of two generalized pseudo-differential operators involving fractional Fourier transform, J. Pseudo Differ. Oper. Appl. 2011, 2(3), 355–365. [CrossRef]

- Toft J.; Bhimani D. G.; Manna R., Fractional Fourier transforms, harmonic oscillator propagators and Strichartz estimates on Pilipovic and modulation spaces, arXiv:2111.09575, 29 pp. [CrossRef]

- Banerji, P. K.; Al-Omari, S. K.; Debnath, L., Tempered distributional sine (cosine) transform, Integral Transforms and Special Functions, 2006, 17(11), 759–768. [CrossRef]

- Prasad A.; Singh M.K., Pseudo-differential operators involving Fractional Fourier cosine (sine) transform, Filomat, 2017, 31(6), 1791–1801.

- Shi, J.; Zheng, J.; Liu, X.; Xiang, W.; Zhang, Q. Novel Short-Time Fractional Fourier Transform: Theory, Implementation, and Applications. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 2020, 68, 3280–3295. [CrossRef]

- Cong, D.Z.; Xu, D.P,; Zhang, J.M.. Fractional S-transform-part 2: Application to reservoir prediction and fluid identification, Applied Geophysics, 2016, 13(2), 343-–352. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Jindal, N.; Singh, A.K., Fractional S-Transform and Its Properties: A Comprehensive Survey, Wireless Pers Commun, 2020, 113, 2519–2541. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhenming, P., The optimal fractional S transform of the seismic signal based on the normalized second-order central moment. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 2016, 129, 8–16.

- Xu, D.P.; Guo, K., Fractional S transform-Part 1: Theory. Appl. Geophys, 2012, 9, 73–79.

- Maksimović S. Fractional Stockwell transform of Lizorkin distributions. Integral transform and Special functions, 2024, 35 (2), 151–163. [CrossRef]

- Thanga Rejini, M.. Generalized fractional Stockwell transform and its associated pseudo-differential operator, Integral Transforms and Special Functions, 2024, 35(11), 637-–653. [CrossRef]

- Mendlovic, D.; Zalevsky, Z.; Mas, D.; García, J.; Ferreira, C., Fractional wavelet transform, Appl. Opt., 1977, 36, 4801–4806.

- Shi, J.; Zhang, N.T.; Liu, X.P., A novel fractional wavelet transform and its applications, Sci. China Inf. Sci., 2011, 55(6), 1270-–1279. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, F.H., Fractional powers of Hankel transforms in the Zemanian spaces, J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1992, 166, 65–83. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, F. H., A fractional power theory for Hankel transforms in L2(R+), J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1991, 158, 114–123. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Saxena, R.; Singh, K., Fractional Fourier Transform and Fractional-Order Calculus-Based Image Edge Detection, Circuits Systems and Signal Processing, 2017, 36(4), 1493–-1513. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, L. F., Image processing utilizing non-positive-definite transfer functions via fractional Fourier transform, Feb. 2000.

- Ran, T.; Bingzhao, L., Theories and methods of signal processing in fractional Fourier domain, Opto-electronic Engineering, 2018, 45 (6), 1.

- Narendra, S.; Aloka, S., Optical image encryption using fractional Fourier transform and chaos, Optics and Lasers in Engineering, 2008, 46 (2), 117–123.

- Jinming, M.; Hongxia, M.; Xinhua, S.; Chang, G.; Xuejing, K.; Ran, T., Research progress in theories and applications of the fractional Fourier transform, Opto-electronic Engineering, 2018, 45 (6), 170747.

- Alieva, T.; Bastiaans, M. M.; Calvo, M. L., Fractional transforms in optical information processing, EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing, 2005, 2005(10), 1498-–1519. [CrossRef]

- Kutay M. A.; Ozaktas, H. M., Optimal image restoration with the fractional Fourier transform, Journal of The Optical Society of America A-optics Image Science and Vision, 1998, 15(4), 825-–833. [CrossRef]

- Singh K.; Nishchal, N. K., Fractional Fourier transform: Applications in information optics, Proc. SPIE 4929, Optical Information Processing Technology, 2002,4929, 34–48.

- Naveen, K. N.; Joby, J,; Kehar, S., Securing information using fractional Fourier transform in digital holography, Optics Communications, 2004, 235 (4–6), 253–259.

- Zunwei, Fu; Yan, L.; Dachun, Y.; Shuhui, Y., Fractional Fourier Transforms Meet Riesz Potentials and Image Processing, 2023, doi: 10.48550/arxiv.2302.13030. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, YS. et al., The Fractional Fourier Transform and its Application to Digital Image Watermarking, in Proc. International Conference on Advanced Maechatronic Systems, 2018, doi: 10.1109/ICAMECHS.2018.8507072.

- Zalevsky, Z.; Ozaktas, H. M.; Kutay, A. M., Fractional Fourier transform-exceeding the classical concepts of signal’s manipulation, Optics and Spectroscopy, 2007, 103(6), 868–-876. [CrossRef]

- Yetik, İ. Ş.; Kutay, M. A.; Ozaktas, H.M., Image representation and compression with the fractional Fourier transform, Optics Communications, 2001 197(4–6), 275–278. [CrossRef]

- Kumari R.; Mustafi, A., Denoising of Images using Fractional Fourier Transform, 2022 2nd International Conference on Emerging Frontiers in Electrical and Electronic Technologies (ICEFEET), Patna, India, 2022, pp. 1-6.

- Nafchi, A. R.; Hamke, E.; Pereyra, C.; Jordan, R., Circular Convolution and Product Theorem for Affine Discrete Fractional Fourier Transform, arXiv: Signal Processing, Oct. 2020.

- Nassiri, M.; Baghersalimi, G.; Ghassemlooy, Z., Optical OFDM based on the fractional Fourier transform for an indoor VLC system, Applied Optics, 2021, 60(9), 2664-–2671. [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.-C.; Xu, D.-P.; Zhang, J.-M., Fractional S Transform — Part 2: Application to Reservoir Prediction and Fluid Identification, Applied Geophysics, 2016, 13(2), 343–352. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, A.; Kumar, S. A Robust Approach to Denoise ECG Signals Based on Fractional Stockwell Transform,” Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 2020, doi:10.1016/J.BSPC.2020.102090. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, A.; Kumar, S., QRS Complex Detection Using Fractional Stockwell Transform and Fractional Stockwell Shannon Energy Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Wang, H.; Zha, D.; Li, P.; Xie, H.; Mao, L., Applications of Fractional Lower-Order S Transform Time–Frequency Filtering Algorithm to Machine Fault Diagnosis, PLOS ONE, 2017, 12(4):e0175202. [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Zhang Y.; Li, Y. -M., Linear Canonical Stockwell Transform: Theory and Applications, IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 2022, 70, 1333–1347.

- Singh K.; Kumar, S., A Spectral Graph Fractional Stockwell Transform for Signal Analysis, Traitement du Signal, 2024, 41(3), 1539–1546. [CrossRef]

- Maksimovic S.; Gajic, S., Stockwell Transform and Its Modifications in Signal Processing Courses: Comparison and Features, in Proc. INFOTEH, 2023,.

- Ranjan, R.; Jindal, N.; Singh, A., Fractional S-Transform and Its Properties: A Comprehensive Survey, Wireless Personal Communications, 2020, 13, 2519–-2541. [CrossRef]

- Mendlovic, D.; Zalevsky, Z.; Mas, D.; Garcia, J.; Ferreira, C., Fractional wavelet transform, Applied Optics, 1997, 36(20), 4801-–4806.

- Shi, J.; Zhang, N.; Liu, X., A novel fractional wavelet transform and its applications, Science in China Series F: Information Sciences, 2012, 55(12), 2753–-2764. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, N., Multiresolution analysis and orthogonal wavelets associated with fractional wavelet transform, Signal, Image and Video Processing, 2015, 9, 211-–220. [CrossRef]

- Zayed, Ahmed I. Fractional Integral Transforms: Theory and Applications. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2024.

- Jindal, N.; Singh, K., Applicability of fractional transforms in image processing—review, technical challenges and future trends, Multimedia Tools and Applications, 2019, 78(2 ), 34303–-34333. [CrossRef]

- Xiaojun Xu; Youren, W.; Shuai, C., Medical image fusion using discrete fractional wavelet transform, Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 2016, 27, 103-–111.

- Guo, C., The application of fractional wavelet transform in image enhancement, International Journal of Computers and Applications, 2021, 43(6), 528-–534. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Novel image denoising method based on discrete fractional orthogonal wavelet transform, in Proc. Conf. CNKI, 2014.

- Yuanyuan, J.; Youren, W.; Hui, L., Image denoising method for unknown noise based on 2-D FWT with optimal fractional order, Journal of Computers, 2014, 9(2), 412–-419.

- Luo, Y.; Yang, L., LFM signal optimization time–fractional–frequency analysis: Principles, method and application, Digital Signal Processing, 2022, 126, 103505,.

- Alieva, T.; Bastiaans, M. J. M., Mode analysis in optics through fractional transforms,” Optics Letters, 1999, 24(17):1206-1208. [CrossRef]

- Alieva, T.; Bastiaans, M. J. M.; Calvo, M. L., Fractional cyclic transforms in optics: Theory and applications, In book: Recent Research Developments in Optics, Research Signpost, Trivandrum, 2001.

- Ge, F.; Zhao, D.; Wang, S., Fractional Hankel Transform and the Diffraction of Misaligned Optical Systems, Journal of Modern Optics, 2005, 52(1), 61–71. [CrossRef]

- Mei Z.; Zhao, D., Propagation of Laguerre–Gaussian and Elegant Laguerre–Gaussian Beams in Apertured Fractional Hankel Transform Systems, Journal of the Optical Society of America A, 2004, 21, 2375–2381.

- Ünalmış Uzun, B., Fractional Hankel and Bessel Wavelet Transforms of Almost Periodic Signals, Journal of Inequalities and Applications, 2015, 388. [CrossRef]

| Signal | Mat. Expression | Parameters / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| (i) | ||

| (ii) | ||

| (iii) | , | |

| G. envelope centered at |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).