1. Introduction

Post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE) is a well-recognized consequence of traumatic brain injury (TBI), accounting for approximately 6% of all epilepsy cases [

1]. TBI represents a major epidemiological risk factor for the development of seizures, increasing the likelihood of epilepsy by up to fourfold compared with individuals without prior head injury [

2]. The severity of the trauma further modulates this risk, with higher incidence observed in cases involving parenchymal damage or intracranial haemorrhage [

3] (see

Table 1 for Diagnostic Criteria of PTE). Seizures may result not only from the direct insult but also from secondary pathophysiological mechanisms, including alterations in neurotransmitter regulation, ionic imbalance, and blood–brain barrier disruption [

4].

PTE deserves clinical attention, as recurrent seizures may exacerbate cognitive decline and worsen the neurological prognosis after TBI [

5]. Indeed, the typical sequelae of TBI include motor impairments—such as weakness, spasticity, and incoordination [

3,

6]—and cognitive deficits, particularly within attentional and executive domains [

7]. Epilepsy itself is also associated with motor and cognitive disturbances, including slowed psychomotor speed, attentional difficulties, visuospatial dysfunction, memory deficits, and impaired executive functioning [

8], which may persist chronically and negatively affect quality of life [

9,

10].

Pharmacological treatment with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) remains the mainstay therapy for PTE [

3]. However, drug resistance is common in this population [

11,

12], and AEDs may interfere with rehabilitation processes such as cognitive and motor training [

13,

14]. Their side effects frequently impact well-being and may not guarantee adequate seizure control [

15]. Surgical intervention is rarely indicated in PTE, and a recent meta-analysis showed higher rates of adverse events following surgery in this population [

5]. These limitations highlight the need for alternative, non-pharmacological and non-invasive therapeutic strategies.

In this context, we present a rehabilitative approach integrating motor therapy with neurofeedback (NFB), with the aim of optimizing outcomes in patients with PTE and potentially reducing reliance on AEDs. Motor therapy is central to neurorehabilitation after TBI: repetitive, high-intensity training has been shown to significantly enhance motor function [

16,

17] and promote neuroplastic changes, including structural grey matter increases in sensory–motor regions [

18] and functional reorganization through increased activation and connectivity in motor networks [

19,

20]. Moreover, regular physical training may reduce seizure occurrence, support neuroprotection, and improve memory and executive functioning in individuals with epilepsy [

21].

Neurofeedback is a non-invasive neuromodulation technique that provides individuals with real-time information about their brain activity, enabling volitional modulation of neural oscillations through operant conditioning [

22]. In epilepsy, NFB protocols typically target the sensorimotor system to reduce cortical excitability and increase thalamocortical inhibition, thereby lowering seizure susceptibility and offering a non-pharmacological therapeutic alternative [

23,

24]. Promising results have also been reported in TBI populations, where NFB has improved cognitive functions—such as attention, memory, and emotional regulation [

25,

26,

27]—as well as other impairment domains including balance, swallowing, and bladder control [

28].

Despite growing evidence supporting NFB efficacy, studies combining neurofeedback with other rehabilitation modalities in PTE remain scarce. To date, only one case report has described NFB integrated with hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) in a patient with PTE, demonstrating improvements in executive function, visuospatial memory, motor performance, language, and somatosensory processing [

29]. However, HBOT requires highly specialized equipment and is associated with potential adverse effects [

30], limiting its clinical applicability.

Here, we propose a more accessible and tolerable multimodal approach, combining NFB with conventional motor therapy. Through this case study, we aim to contribute to the emerging evidence supporting integrated neuromodulatory and rehabilitative strategies for managing epilepsy following TBI.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria of Epilepsy secondary to Traumatic Brain Injury (Post-Traumatic Epilepsy, PTE) [

3,

31,

32].

Table 1.

Diagnostic Criteria of Epilepsy secondary to Traumatic Brain Injury (Post-Traumatic Epilepsy, PTE) [

3,

31,

32].

| Diagnostic criteria Post-Traumatic Epilepsy (PTE) |

|---|

| History of TBI with moderate to severe injury (risk is highest with: penetrating injuries, intracranial hemorrhage, depressed skull fracture) |

| First seizure > 7 days post injury |

| No other identifiable causes of seizures |

| Supporting Tests: EEG abnormalities, neuroimaging consistent with post-traumatic sequelae |

| Early seizures (< 7 days) are considered acute symptomatic and do not alone establish epilepsy. |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Presentation

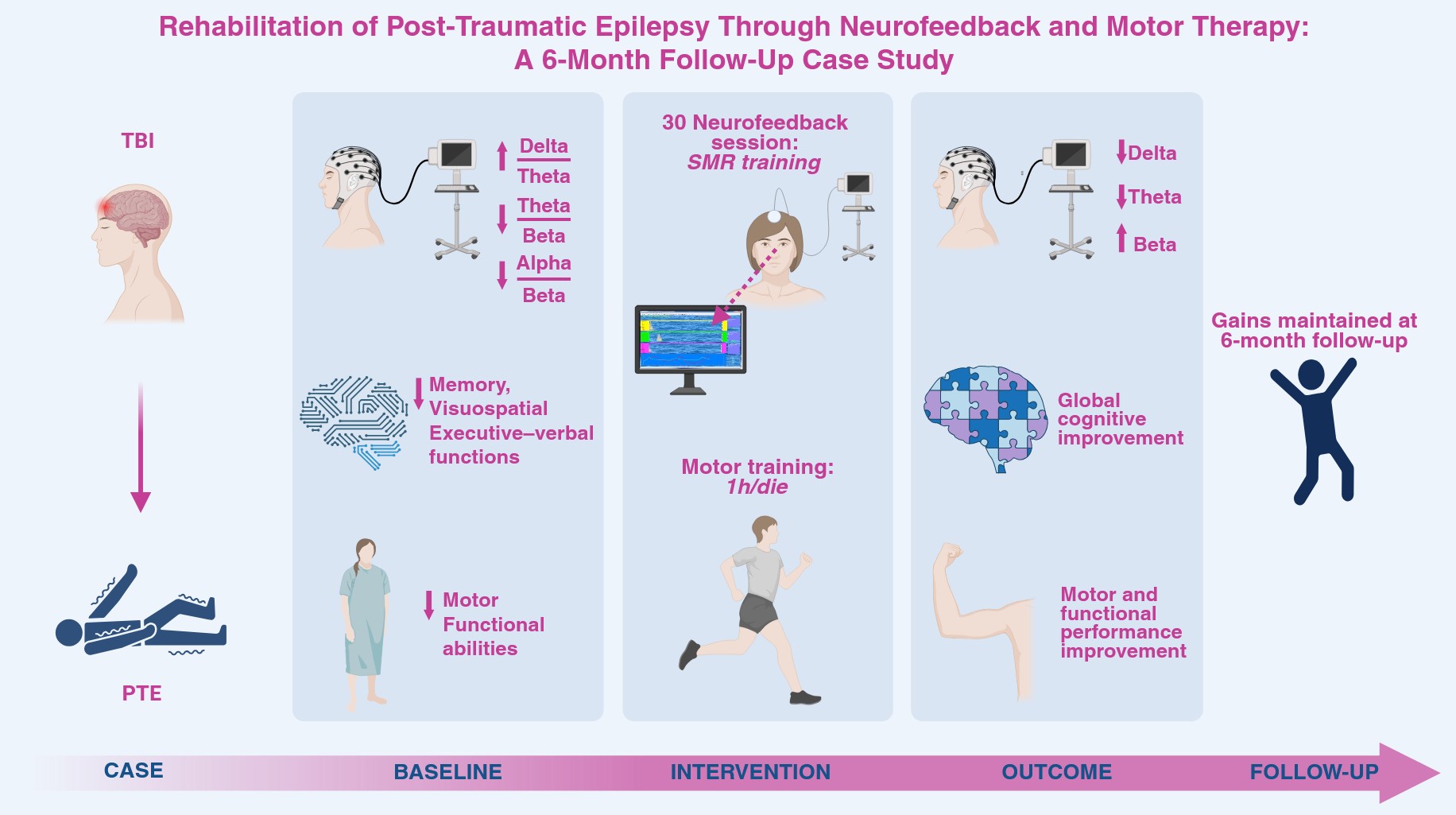

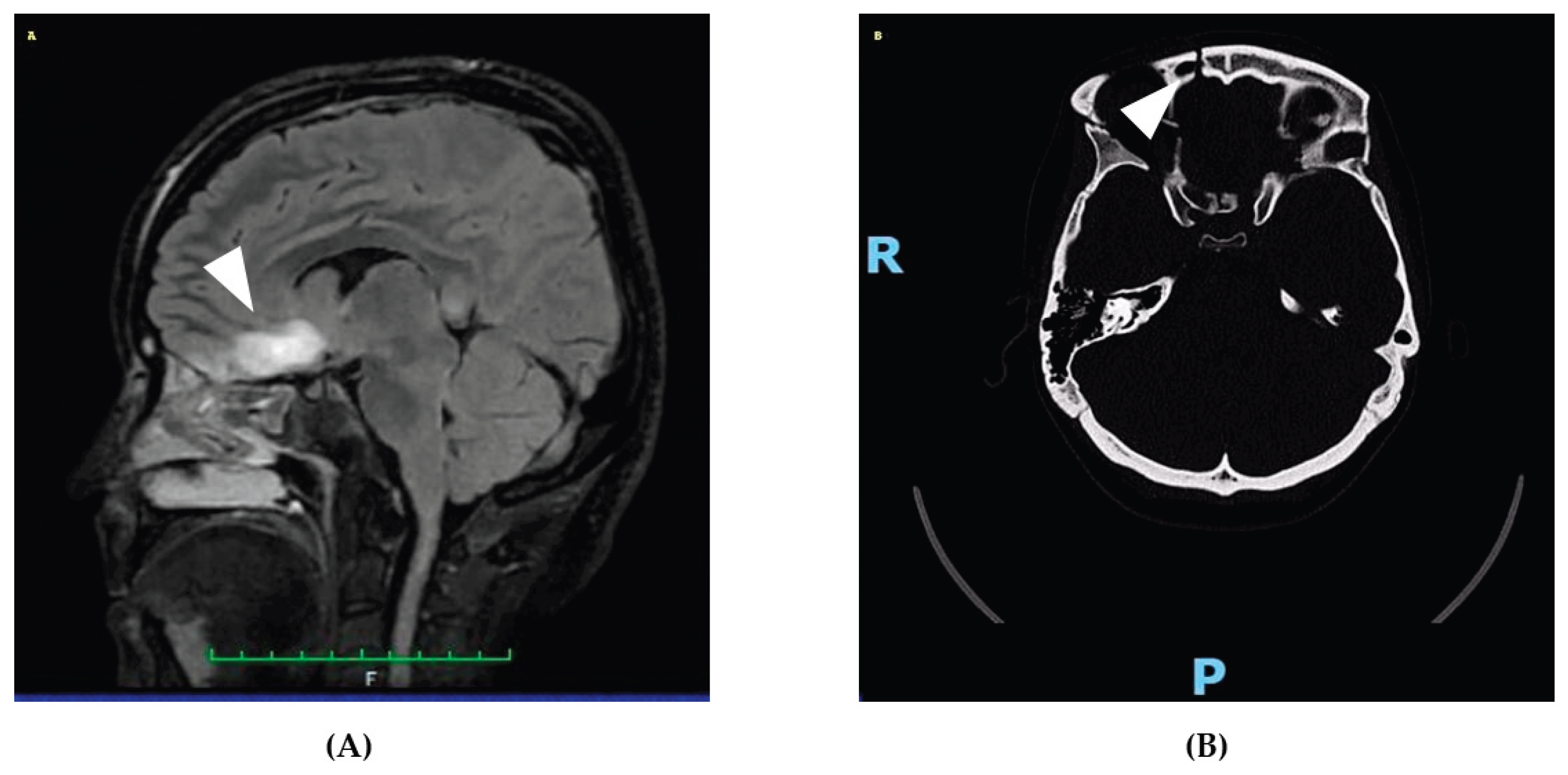

On April 21st, 2025, a 31-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department following a high-impact car accident resulting in multiple traumatic injuries. She had no relevant past medical history and no smoking, alcohol, or substance use habits. She had completed 13 years of education and was employed. At initial evaluation, she appeared alert but partially oriented, exhibiting mild psychomotor agitation while remaining cooperative with medical staff. Whole-body computed tomography (CT) revealed bilateral intraparenchymal cerebral contusions, multiple splanchnocranial fractures with orbital involvement, paraseptal emphysema at the level of the pulmonary hilum, and focal lingual post-contusion consolidation. On April 24th, she was transferred to the neurosurgery department for further maxillofacial, ophthalmologic, and thoracic assessments. On April 27th, during hospitalization, the patient experienced a generalized comitial crisis accompanied by hyponatremia and new-onset anisocoria. A repeat CT scan showed no acute changes compared to previous imaging. Due to worsening neurological status, she was transferred to the intensive care unit, where she required intubation and underwent a brain MRI (

Figure 1). MRI findings demonstrated artifacts consistent with diffuse axonal injury, along with cytotoxic edema involving the pituitary gland and the pericallosal pedicle. Following stabilization, she was extubated on May 6th and underwent a neurological examination. She was awake, cooperative, and able to move all four limbs symmetrically, with no signs of paresis or abnormal posturing. A mild reduction in muscle strength was observed, likely attributable to prolonged immobilization. Pupils were isochoric and reactive to light. Her neurological condition was deemed clinically stable, and she was transferred back to the neurosurgery ward. On May 15th, a maxillofacial examination confirmed consolidation of Craniomaxillofacial Orbitozygomatic (COMZ) fractures. A small, slightly displaced bone fragment persisted in the periorbital region but did not result in functional impairment, as confirmed by a subsequent ophthalmological evaluation. The patient nonetheless reported a persistent foreign body sensation and pain during ocular movements, likely due to impingement of the displaced fragment on the oblique ocular muscle. Given her progressive medical stabilization, on May 21st, 2025, the patient was transferred to the IRCCS Maugeri Institute for post-acute intensive neurorehabilitation (see

Table 2 for Clinical Case Overview).

2.2. Neuromotor and Functional Assessment

At admission to the rehabilitation unit, the patient was alert, conscious, cooperative, and fully oriented to time and place, although she presented with ideomotor slowing and short-term memory deficits. Comprehension was intact, and she was able to understand and follow simple commands. No language disturbances, dysarthria, or meningeal signs were observed, and swallowing function was preserved. Mobility was partially independent: she could ambulate without assistive devices, although occasional support was required for positional transitions. Verticalization was achieved with good trunk control; however, gait was ataxic. Cerebellar testing—including finger-to-nose, heel-to-shin, rapid alternating movements, and tandem walking—revealed impaired coordination. Cranial nerve examination showed restricted horizontal gaze, more pronounced on the right side, associated with pain during ocular movements and intermittent diplopia. Cervical range of motion was preserved in all planes, though flexion and rotation elicited tenderness. Palpation revealed soreness of the paravertebral cervical musculature and trapezius muscles. Muscle tone was normal, yet multi-segmental muscular hypotrophy was evident. Upper limb strength was graded between MRC 3 and 4, while lower limb endurance was reduced on the Mingazzini II test. Deep tendon reflexes were normal, sensation was preserved across all dermatomes, and plantar flexion remained intact. A 7 cm longitudinal wound was present in the right frontal region as a result of craniofacial trauma. The wound appeared mildly erythematous, non-exudative, and tender to palpation, with oedema extending toward the right temporo-orbital area. Bladder and bowel continence were preserved. Functional performance was quantified through standardized physiotherapy measures. At admission, the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test measured 9.94 seconds, indicating moderate mobility. The Trunk Control Test (TCT) score was 45/100, the Barthel Index measured 70/100, and the Rehabilitation Complexity Scale–Extended (RCS-E) score was 8, reflecting moderate care complexity and partial dependence in activities of daily living.

2.3. EEG Assessment

Electroencephalographic (EEG) evaluations were conducted at two time points—May 27th, 2025, and July 14th, 2025—as part of routine follow-up after traumatic brain injury associated with a recent epileptic seizure. The baseline EEG (May 27th, 2025) was performed to assess the patient’s electrophysiological status following the road traffic accident and the subsequent acute seizure. At the time of the recording, the patient was receiving Levetiracetam (500 mg twice daily) and presented with spontaneous and command-induced eye opening, oriented verbal responses, and good overall cooperation. The recording lasted 21 minutes and incorporated standard activation procedures, including eye opening and closure, hyperventilation, intermittent photic stimulation (3–30 Hz), and auditory stimuli. Minor technical limitations were noted due to reduced electrode contact at occipital sites (O1 and O2), attributed to hair knots, although the overall recording quality remained sufficient for interpretation. Background activity appeared substantially symmetrical, characterized by intermittent Alpha rhythmic sequences in posterior regions. A prominent finding was the frequent presence of bilateral Theta-band slow waves, displaying subtle parasagittal predominance. These waveforms were often synchronous across hemispheres, showed markedly higher amplitude compared to the physiological background, and occurred in 5 Hz runs lasting up to 6 seconds. Additionally, rare isolated graphoelements of uncertain epileptiform morphology—possibly representing sharp waves followed by slow waves—were observed, although without consistent topographic localization.

2.4. Rehabilitation Procedure

This single-case study was conducted at the Neurorehabilitation Unit of ICS Maugeri IRCCS in Bari, Italy. The patient, admitted for intensive post-acute rehabilitation following a traumatic brain injury, presented with clinically significant cognitive deficits, as documented through comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation. Before initiating treatment, the patient underwent a baseline quantitative EEG (qEEG) and an extensive neuropsychological assessment to characterize cognitive functioning and establish pre-intervention measures. The rehabilitation program integrated 30 NFB sessions, each lasting 35 minutes, administered five times per week over a three-week period. NFB training was combined with one hour of daily conventional motor rehabilitation, aimed at supporting physical recovery and improving functional independence. The motor rehabilitation component targeted overall clinical stabilization and progressive mobilization. Interventions focused on global muscle strengthening—particularly involving core musculature and multi-district muscle groups—joint mobility, postural control, and the modulation of reflex spasticity. Functional exercises were tailored to progressively enhance motor coordination, endurance, and autonomy in daily activities. At the end of the combined intervention, the patient completed a follow-up qEEG as well as repeated neuropsychological and motor assessments, allowing evaluation of post-treatment changes across cognitive, electrophysiological, and functional domains.

2.5. EEG Acquisition and Data Processing

QEEG recordings at rest were acquired before and after the intervention using a 21-channel BE PLUS PRO system (EBNeuro, Italy), with electrodes positioned according to the international 10–20 system. All data were processed offline using NeuroGuide software (version 3.0.6, Applied Neuroscience Inc., USA). Trained examiners (NB and LL) performed visual inspection and manual artifact rejection, yielding at least two minutes of artifact-free EEG per recording. Both split-half and test–retest reliability exceeded 0.9, in line with established methodological standards.

Spectral analysis included the conventional frequency bands: Delta (1–4 Hz), Theta (4–8 Hz), Alpha (8–12 Hz), Beta (12–25 Hz), High-beta (25–30 Hz), Gamma (30–40 Hz) and High-Gamma (40–50 Hz). Additional sub-band analyses were conducted—such as Low-Alpha (8–10 Hz) and High-Alpha (10–12 Hz)—to refine the characterization of Alpha-range dynamics. Commonly employed power ratios, including Delta/Alpha, Theta/Beta and Alpha/High-beta, were also calculated to capture broader aspects of spectral organization and cortical arousal regulation, following standard qEEG analytical frameworks [

33].

2.6. Neuropsychological Assessment

During her hospitalization in the Neuromotor Rehabilitation Unit 2, the patient underwent comprehensive neuropsychological evaluations at the beginning and at the end of her rehabilitation program. These assessments were carried out to objectively compare her cognitive performance over time and to identify possible improvements in her cognitive–linguistic profile. At the time of the clinical interview, she presented in generally good condition, was alert and cooperative, and demonstrated appropriate awareness of her medical situation. Orientation with respect to time and space was intact, and she appeared reliable in terms of autobiographical recall, providing structured and coherent information about her personal background and family history. Remote memory appeared preserved; however, she reported difficulty recollecting the events surrounding the accident as well as other emotionally salient experiences from the previous year, suggesting a possible impairment in recent episodic memory. She also described visual disturbances, including blurred vision and the perception of shadows in the peripheral visual field. Spontaneous speech was normo-fluent, intelligible, and well-articulated, with no evidence of dysarthria or anomia. Comprehension of both simple and complex sentences was intact, allowing for effective and functional communication. The patient’s mood during the assessment appeared within normal limits, and her facial expressions and gestures were congruent with both her verbal output and the clinical context. Responses during the interview were relevant, coherent, and logically organized. Although she remained cooperative throughout the evaluation, she exhibited occasional moments of fatigue, likely related to the hospital environment and her overall clinical condition. To assess her neurocognitive functioning in a structured and objective manner, validated and clinically reliable neuropsychological tests were administered. Parallel forms were used during the second evaluation to minimize learning effects. The assessment covered a broad range of cognitive domains, including overall cognitive functioning, attentional and executive abilities, verbal and visuospatial memory, visuoconstructive skills, and language.

2.7. Neurofeedback Training

NFB training was delivered using the ProComp5 system in combination with the Biograph Infiniti software (Thought Technology, Montreal, Canada), following established EEG biofeedback guidelines [

34]. Electrode placement conformed to the international 10–20 system. The active electrode was positioned at Cz for the first fifteen sessions and subsequently moved to Fz for the remaining sessions, a decision informed by the anatomical location of the traumatic brain injury and supported by findings from the baseline qEEG evaluation. Electrode impedance was consistently kept below 5 kΩ throughout all sessions to ensure signal reliability. Each NFB session lasted thirty-five minutes and incorporated both visual and auditory feedback delivered through a gamified interface, specifically a “boat race” task designed to promote engagement and reinforce the desired EEG patterns. The training protocol was individualized and aimed at enhancing the sensorimotor rhythm (SMR; 12–15 Hz) while concurrently suppressing Theta (4–7.5 Hz) and High-beta (22–26 Hz) activity. Thresholds were adaptively adjusted in real time by the clinician to maintain an optimal level of task difficulty and participant responsiveness; typically, the goal was to achieve approximately seventy percent reinforcement for the reward frequency band and around twenty percent reinforcement for the inhibition bands. Protocol selection was grounded in the patient's clinical presentation and baseline qEEG findings. SMR/Theta training was chosen due to its demonstrated effectiveness in managing epilepsy and in improving deficits related to motor planning and arousal regulation. The personalized NFB intervention was designed to promote voluntary modulation of cortical oscillations and to support neuroplastic changes through Hebbian learning principles and homeostatic regulatory mechanisms [

35,

36].

2.8. Statistical Analyses

QEEG analyses were performed on recordings obtained under Eyes Closed (EC) and Eyes Open (EO) resting-state conditions at two time points, pre- and post-intervention. Data extraction focused on three electrode sites—Fz, Cz, and Pz—and included measures of absolute power, relative power, and power ratios across the standard frequency bands (Delta, Theta, Alpha, Beta, and High-beta). Prior to processing, non-relevant summary rows, such as global averages, were removed to retain only electrode-specific values. Each spectral band and ratio were examined through paired pre–post comparisons. The normality of the data distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test; paired-sample t-tests were applied when both pre- and post-intervention values met normality criteria, whereas Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used when normality was violated. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. For each band and ratio, mean and standard deviation values were calculated at both time points. Power ratios analyzed included Delta/Theta, Theta/Beta, Alpha/Beta, Theta/High-beta, Alpha/High-beta, and Beta/High-beta, providing insight into frequency-specific changes related to the intervention. For the EC condition, absolute power variations were additionally illustrated through bar plots showing mean ± standard deviation, with statistically significant differences indicated for ease of interpretation. To explore broader temporal trends in EEG absolute power, a third assessment time point was added at a six-month follow-up. A non-parametric repeated-measures analysis was conducted on aggregated data across all scalp positions for each frequency band. Median and interquartile range (IQR) values were calculated for the Pre-treatment, Post-treatment, and Follow-up evaluations. The Friedman test was used to assess overall changes across time, followed by pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to evaluate differences between Pre and Post, Post and Follow-up, and Pre and Follow-up. P-values from the pairwise comparisons were corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg (BH) procedure to control for multiple comparisons. This analytic framework allowed us to assess both immediate and sustained electrophysiological effects of the intervention. Clinical reliability of cognitive and emotional changes was examined using the Reliable Change Index (RCI). The RCI determines whether observed differences between pre- and post-intervention scores exceed the range expected due to measurement error, based on each test’s standard deviation and test–retest reliability. The formulas applied were:

SE = SD × √(1 − r)

RCI = (Xₚₒₛₜ − Xₚᵣₑ)/(SE × √2)

Raw pre- and post-intervention scores were used, and normative standard deviations (SD) and reliability coefficients (r) were obtained from validated Italian neuropsychological datasets appropriate for a 31-year-old woman with 13 years of education. These datasets included norms from Spinnler and Tognoni (1987) [

37], Carlesimo et al. (2014, 1996) [

38,

39] , Orsini et al. (1987) [

40], Novelli et al. (1986) [

41,

42] , Caffarra et al. (2002) [

43,

44], Amato et al. (2002) [

45], Pedrabissi and Santinello (1989) [

46], and Ghisi et al. (2006) [

47]. An RCI value exceeding ±1.96 was interpreted as a statistically reliable change at the 95% confidence level.

3. Results

3.1. EEG Measures

Quantitative EEG analysis revealed clear electrophysiological changes following the intervention. Under eyes-closed conditions, z-scored absolute power showed significant reductions in slow-wave activity, with Delta power decreasing from 2.33 ± 0.45 to –0.10 ± 0.23 (p = 0.0046) and Theta power decreasing from 3.61 ± 1.55 to 1.22 ± 1.06 (p = 0.0155). No significant differences emerged for Alpha, Beta, or High-beta bands. Under eyes-open conditions, Theta absolute power also significantly decreased (Pre: 3.56 ± 1.90; Post: 1.14 ± 1.15; p = 0.0329), while the reduction in Delta power—although numerically large—did not reach significance. Faster frequency bands again remained stable. Full absolute power results are reported in

Table 3.

Analysis of z-scored relative power demonstrated a broader pattern of spectral reorganization. In the eyes-closed condition, Theta relative power significantly decreased (Pre: 2.97 ± 0.99; Post: 1.52 ± 1.03; p = 0.0107), and Beta relative power increased markedly from negative to near-normative values (p = 0.0278), whereas Delta remained unchanged. Under eyes-open conditions, significant improvements emerged across multiple bands: Theta decreased (p = 0.0073), Alpha increased toward normative values (p = 0.0426), and both Beta and High-beta showed significant increases (p = 0.0204 and p = 0.0378), suggesting normalization of fast-wave activity and reduced hyperarousal. See

Table 4 for complete values.

Power ratio metrics further supported these findings. In the eyes-closed condition, the Theta/Beta ratio significantly decreased from 4.01 ± 1.53 to 0.77 ± 1.32 (p = 0.0060), indicating improved cortical activation and attentional control, whereas all other ratios showed non-significant stabilization trends. In contrast, eyes-open ratios revealed more widespread improvements: Theta/Beta (p = 0.0124), Alpha/Beta (p = 0.0032), and Theta/High-beta (p = 0.0262) all decreased significantly, reflecting normalization of arousal and executive-control networks. Related ratio data appear in

Table 5.

3.1.4. EEG Changes at 6 Months Follow up

To examine longer-term electrophysiological trajectories, EEG metrics were also assessed at a six-month follow-up. Analyses of z-scored absolute power across the three time points (Pre, Post, Follow-up) revealed significant time effects for Delta (p = 0.0008), Theta (p = 0.0003), Alpha (p = 0.0015), and Beta (p = 0.0076). Delta and Theta showed consistent and significant reductions from Pre to Post and from Pre to Follow-up, indicating sustained attenuation of cortical slowing. Alpha significantly decreased between Pre and Follow-up, while Beta displayed a transient post-treatment rise before returning toward baseline at Follow-up. High-beta approached significance. All values are presented in

Table 6.

Relative power values also changed significantly over time, with all major frequency bands showing corrected p-values below 0.01. Delta relative power decreased progressively from Pre to Follow-up. Theta and Alpha showed their largest shifts from Pre to Post, while Beta and High-beta increased steadily across the three time points, indicating enhanced fast-frequency engagement and continued normalization of arousal systems. These findings are detailed in

Table 7.

Power ratio analysis across the three time points revealed significant effects for Delta/Alpha (p = 0.0008), Delta/Beta (p = 0.0003), and Delta/High-beta (p = 0.0022), with pairwise tests confirming significant reductions from Pre to Post and Pre to Follow-up. Additional ratios—including Theta/Alpha, Theta/Beta, Theta/High-beta, Alpha/Beta, Alpha/High-beta, and Beta/High-beta—also demonstrated significant long-term improvements, particularly between the Pre and Post assessments and extending into the Follow-up period. These changes reflect a durable shift away from slow-wave dominance and a progressive normalization of oscillatory balance. Comprehensive ratio results are reported in

Table 8.

3.2. Neuropsychological Profile Pre- and Post- NF Training

In regard to the neuropsychological profile, several cognitive domains demonstrated reliable improvement immediately after the intervention, as reported in

Table 9. Global cognitive functioning, measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), increased from 27 to 30 between the Pre- and Post-treatment assessments, yielding a significant RCI of 2.68. This improvement was fully maintained at Follow-up (RCI = 0.00), indicating stable consolidation of global cognition. Executive functioning showed a different pattern. The Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) displayed a modest increase from 16 to 18 immediately after treatment (RCI = 1.79), which did not exceed the reliability threshold. A slight decrease at Follow-up (score = 17; RCI = –0.89) remained within normal variability, suggesting overall stability rather than measurable change.

The strongest and most clinically meaningful improvements emerged in episodic memory. The Rey 15-Word Immediate Recall score increased from 50 to 59 following treatment (RCI = 8.05) and continued to rise to 64 at Follow-up (RCI = 4.47), producing a substantial cumulative RCI of 12.52 from baseline. Similarly, the Rey 15-Word Delayed Recall improved from 6 to 10 at Post-treatment (RCI = 3.58) and further increased to 12 at Follow-up (RCI = 1.79), resulting in a total RCI of 5.37. These changes indicate robust enhancement of both immediate and delayed verbal memory.

Visuoconstructive abilities also improved. Performance on the Figure Copy test increased markedly from 10 to 20 between Pre- and Post-treatment evaluations (RCI = 8.94), followed by a partial regression at Follow-up (score = 14; RCI = –5.37). Despite this decline, the overall improvement from baseline remained reliably positive (RCI = 3.58). The decrease at Follow-up may reflect fluctuations in attention, motivation, or fatigue rather than a loss of treatment benefit. Measures of processing speed and cognitive flexibility, including the Trail Making Test A and the Stroop Color–Word task, showed reliable numerical improvements (such as a reduction in TMT-A time from 54 to 31.2 seconds). Taken together, the RCI analysis demonstrated statistically reliable and clinically meaningful improvements in global cognition, episodic memory, and visuospatial functioning following the intervention, with most benefits either maintained or further enhanced at Follow-up. These results quantitatively support the durability of the cognitive improvements associated with the combined rehabilitation program.

3.2. Motor Changes Pre- and Post- NFB Training

RCI analysis revealed significant improvements across most measures between baseline and discharge (see

Table 10). All six assessments—TUG, TCT, Barthel Index, FIM, RCS-E, and MRC—showed statistically reliable change. Notably, TUG and RCS-E scores decreased significantly, indicating better mobility and consciousness levels, while TCT, Barthel, FIM, and MRC scores increased, reflecting improved trunk control, independence in daily activities, and muscle strength.

Between discharge and follow-up, the Barthel Index, FIM, RCS-E, and TUG continued to show statistically reliable improvements, though changes were generally smaller. TCT and MRC remained stable, suggesting that the most substantial recovery occurred during the inpatient phase, with some continued gains post-discharge.

Overall, the results suggest that rehabilitation led to meaningful functional gains, most notably during the initial intervention period, with ongoing, though more modest, progress after discharge.

4. Discussion

PTE is one of the most prevalent and impairing outcomes of TBI, potentially worsening motor and cognitive deficits typically present after head injury [

5]. From a therapeutic point of view, PTE is an especially challenging condition to treat, since both medications (i.e. antiepileptic drugs) and surgical procedures did not yield encouraging outcomes, increasing the load on patients and caregivers [

3,

11,

12]. Therefore, there is a compelling need for new and successful treatment options for this condition.

The present case study reveals encouraging neuropsychological and neurophysiological outcomes following a 30-session neurofeedback training, combined with traditional motor therapy, in a patient with epilepsy secondary to TBI. The combined treatment allowed exploitation of the plasticity time window from both top-down and bottom-up perspectives. Previous literature supported the beneficial effects of neurofeedback on the modulation of cortical oscillations and network plasticity. In particular, SMR training has been shown to promote thalamocortical inhibition and stabilize cortical excitability, which may reduce seizure susceptibility while enhancing attentional regulation and cognitive control [

35,

48] and neurofeedback of Beta-activity has been extensively employed with positive outcomes in the treatment of attention impairments and motor issues after TBI [

49]. More recently, EEG-based neurofeedback resulted in significant improvements in attention, processing speed and visuo-spatial abilities, with even better outcomes than traditional methods [

50,

51], suggesting that neurofeedback may engage neuroplastic mechanisms underlying functional recovery [

22]. Furthermore, these mechanisms are believed to act via Hebbian learning principles, strengthening functional connectivity and optimizing arousal regulation [

52].

As regards PTE, neurofeedback offers a promising non-compound and alternative treatment option. To our knowledge this is only the second case study that focuses on the rehabilitative effects of neurofeedback on this common condition, extending pre-existing evidence by evaluating the long-term impact of the neuromodulatory intervention. While earlier analyses primarily focused on immediate pre- to post-treatment changes, the inclusion of a 6-month follow-up allowed us to assess the stability and durability of these effects over time. This longitudinal perspective provides valuable insight into whether the observed neural modulations represent transient adjustments or more enduring adaptations in brain function.

The results of this training reveal reliable and sustained improvements of general cognition and, more specifically, of long-term verbal and visuospatial memory, attentional-executive functioning, and praxic-constructive abilities, whose initial impairment could be well explained by the frontal site of the lesions and might be potentially due also to disruptions of the connections between the frontal area and other brain regions [

53]. The increase in MMSE score, sustained at follow-up, suggests an actual enhancement in overall cognitive functioning but the most robust effects emerged in the memory domain, with significant and sustained increases in both immediate and delayed recall on the Rey 15-Word Test. This pattern supports the hypothesis that the intervention facilitated long-term strengthening of memory processes, likely through neuroplastic mechanisms. Visuoconstructive abilities also improved, as evidenced by the Figure Copy test scores, although a partial decline at follow-up can be observed. Notably, executive functioning showed a positive change across time. The cognitive improvements are mirrored also by changes at the neurophysiological level after the training. Quantitative EEG analyses revealed a statistically significant reduction in Delta power under EC conditions and this effect remained robust even after correction for multiple comparisons. This may reflect improved cortical engagement or increased functional efficiency following intervention. The maintenance of this effect at follow-up suggests that the treatment had a lasting impact on slow-wave neural dynamics, which could be clinically relevant for individuals with dysregulated resting-state activity. Moreover, prominently Theta and Beta1 frequency bands demonstrated trending reductions in both EC and EO conditions across absolute and relative power measures. Although these effects did not reach significance after correction, they exhibited consistent patterns of change that were sustained at the 6-month mark. The absence of significant differences between post and follow-up time points in these bands strengthens the interpretation that the intervention induced stable shifts in neural oscillatory activity, rather than transient fluctuations. Moreover, the observed normalization of EEG ratios, particularly the Theta/Beta and Theta/High-beta ones, further supports the noticed cognitive improvements, since increased Theta power seems to be indicative of impaired cognitive abilities, especially in executive functioning and attention [

54,

55,

56]. The significant reduction in these ratios implies enhanced cortical inhibition, which aligns with previous studies arguing that SMR NFB mechanisms may promote brain rhythm synchronization, inhibition of cortical hyperarousal, decreased in seizure frequency and severity and decreased spike activity in patients with seizures secondary to TBI [

29,

57]. Summing up, here we extended pre-existing evidence of SMR training being useful for EEG normalization. Specifically, we found significant reduction of slow-wave bands, other than the stabilization of faster activity, already observed in the previous case study by White et al. (2022) [

29]. Future research might explore whether combining EEG changes with behavioral or clinical outcome measures could further clarify the practical relevance of these neurophysiological findings.

The observed significant reductions in depressive and anxiety symptoms further reflect brain rhythms normalization. As previous studies suggest, neurofeedback has been associated with affective regulation in patients with TBI and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [

58,

59,

60]. Specifically, a reduction of High-beta power, which has been observed in this case, is known to be linked to a decrease in brain state hyperarousal and in depressive symptoms and anxiety [

56].

From a motor and functional perspective, the patient exhibited reliable and clinically meaningful improvements in motor performance and autonomy. Initial deficits in coordination, balance and gait are representative of the most common sequelae of TBI [

61]. However, enhanced trunk control, mobility, and daily living independence (as indexed by increases in TCT, Barthel Index, FIM, and MRC scores, and by reductions in TUG and RCS) indicate that the integrated intervention supported both cortical and subcortical recovery processes. In fact, the patient showed normalized gait and balance, adequate cerebellar performance, and full management of transfers and ambulation. Ocular motility was symptom-free, lower-limb endurance was normal, and trunk control reached maximal scores. Residual issues were mild orofacial discomfort, persistent anosmia and ageusia, and a non-exudative frontal wound with reduced oedema.

The persistence of these gains beyond discharge suggests that neurofeedback may have contributed to strengthening motor learning mechanisms and improving sensorimotor integration. These findings align with previous studies on the role of neurofeedback in improving motor function and balance in TBI patients [

28].

Despite these encouraging outcomes, some limitations of our study must be acknowledged. Firstly, the generalizability of these findings may be limited, because they come from a single-case study and also because of the type of treatment we chose to apply. Neurofeedback is a rehabilitative approach that requires active cooperation and motivation from the patient, showing no benefits, on average, on 25 to 30% of patients (i.e. “non-responders”). This may depend on multiple factors such as trusting and understanding the mechanisms of neurofeedback or volume of some brain structures [

22]. Secondly, the absence of a control condition hinders potential causal inferences and possible confounding variables cannot be excluded.

In conclusion, this case provides converging electrophysiological and behavioural preliminary evidence that SMR NFB, when integrated with motor rehabilitation, can promote sustained neurophysiological, cognitive-emotional, and functional recovery, harnessing neuroplasticity for long-term cortical reorganization, in a common condition, such PTE, that has not been sufficiently addressed by literature yet.

5. Conclusions

PTE is a frequent consequence of TBI, often resistant to pharmacological treatments. This case study investigates the combined effects of SMR NFB training and motor therapy in a patient with this condition. This intervention yielded reliable improvements in global cognition, episodic memory, visuoconstructive abilities, and attentional-executive functioning, accompanied by significant EEG changes, including reductions in slow-wave activity and normalization of faster frequencies, that were maintained at 6-month follow-up, suggesting durable enhanced cortical inhibition and neural efficiency. Motor performance and functional independence also improved, reflecting better sensorimotor integration. Emotional outcomes mirrored neural stabilization, with decreased anxiety and depression symptoms. Overall, these findings extend previous evidence supporting SMR NFB as a promising adjunctive therapy for PTE, promoting cognitive, emotional, and functional recovery.

Author Contributions

A.L.,G.L.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Project Administration; N.B.: Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing; L.L.: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation; R.P.,L.D.: Clinical Assessment, Participant Recruitment, Data Collection, Writing – Review & Editing; P.F.: Data Collection, Patient Coordination; F.M.: EEG Acquisition, Methodology, Review & Editing; P.B.: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing; S.D.T.: Supervision, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing; G.L.: Supervision, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Ricerca Corrente funding from the Italian Ministry of Health to Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri IRCCS.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for both clinical data use and publication of de-identified EEG and neuroimaging figures.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional policies and ethical restrictions protecting patient confidentiality. However, anonymized data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to appropriate ethical approval.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the patient, whose cooperation and willingness to participate made this case report possible. Her active involvement and informed consent allowed for detailed and rigorous documentation of the entire rehabilitation process. Special thanks are also extended to the multidisciplinary team of NeuroRehabilitation Unit of IRCCS Maugeri Bari for their continuous clinical support which was essential to the patient’s management and treatment. The authors further wish to acknowledge Engineer Simona Aresta and Luca Righetto for their valuable technical support and their assistance in managing the technological and instrumental components of this case.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. .

References

- Szaflarski, J.P.; Nazzal, Y.; Dreer, L.E. Post-traumatic epilepsy: current and emerging treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2014, 10, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui S, Sun J, Chen X, et al. Risk of Epilepsy Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2023; 38: E289–E298.

- Lowenstein, D.H. Epilepsy after head injury: an overview. Epilepsia 2009, 50 (Suppl 2), 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding K, Gupta PK, Diaz-Arrastia R. Epilepsy after Traumatic Brain Injury. In: Laskowitz D, Grant G, Hrsg. Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group; 2016.

- Pease M, Gupta K, Moshé SL, et al. Insights into epileptogenesis from post-traumatic epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol 2024; 20: 298–312.

- Shrivastava A, Dwivedi S, Gupta P, et al. A review of current status of epilepsy after traumatic brain injuries: Pathophysiology, clinical outcomes, and emerging treatment strategies. AccScience Publishing 2025; 4: 1–16.

- Wilson L, Stewart W, Dams-O’Connor K, et al. The chronic and evolving neurological consequences of traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 813–825.

- Novak A, Vizjak K, Rakusa M. Cognitive Impairment in People with Epilepsy. J Clin Med 2022; 11. [CrossRef]

- Cho S-J, Park E, Baker A, et al. Post-Traumatic Epilepsy in Zebrafish Is Drug-Resistant and Impairs Cognitive Function. J Neurotrauma 2021; 38: 3174–3183.

- Ngadimon IW, Aledo-Serrano A, Arulsamy A, et al. An Interplay Between Post-Traumatic Epilepsy and Associated Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review. Front Neurol 2022; 13: 827571.

- Golub, V.M.; Reddy, D.S. Post-Traumatic Epilepsy and Comorbidities: Advanced Models, Molecular Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Novel Therapeutic Interventions. Pharmacol Rev 2022, 74, 387–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.; Chen, J.W.Y. Treatment of post-traumatic epilepsy. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2012, 14, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pingue, V.; Mele, C.; Nardone, A. Post-traumatic seizures and antiepileptic therapy as predictors of the functional outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple BD, Zamani A, Rayner G, et al. Affective, neurocognitive and psychosocial disorders associated with traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis 2019; 123: 27–41.

- Chmielewska, N.; Szyndler, J. Innovations in epilepsy treatment: pharmacological strategies and machine learning applications. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2025, 59, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang P-FJ, Baxter MF, Rissky J. Effectiveness of Interventions Within the Scope of Occupational Therapy Practice to Improve Motor Function of People With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Am J Occup Ther 2016; 70: 7003180020p1–p5.

- Subramanian SK, Fountain MK, Hood AF, et al. Upper Limb Motor Improvement after Traumatic Brain Injury: Systematic Review of Interventions. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2022; 36: 17–37.

- Gauthier LV, Taub E, Perkins C, et al. Remodeling the brain: plastic structural brain changes produced by different motor therapies after stroke. Stroke 2008; 39. [CrossRef]

- Schaechter, J.D. Motor rehabilitation and brain plasticity after hemiparetic stroke. Prog Neurobiol 2004, 73, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepert J, Uhde I, Gräf S, et al. Motor cortex plasticity during forced-use therapy in stroke patients: a preliminary study. J Neurol 2001; 248: 315–321.

- Cavalcante BRR, Improta-Caria AC, Melo VH de, et al. Exercise-linked consequences on epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2021; 121: 108079.

- Loriette, C.; Ziane, C.; Ben Hamed, S. Neurofeedback for cognitive enhancement and intervention and brain plasticity. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2021, 177, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egner, T.; Sterman, M.B. Neurofeedback treatment of epilepsy: from basic rationale to practical application. Expert Rev Neurother 2006, 6, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, M.B.; Egner, T. Foundation and practice of neurofeedback for the treatment of epilepsy. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2006, 31, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen P-Y, Su I-C, Shih C-Y, et al. Effects of Neurofeedback on Cognitive Function, Productive Activity, and Quality of Life in Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2023; 37: 277–287.

- Brown, J.; Clark, D.; Pooley, A.E. Exploring the Use of Neurofeedback Therapy in Mitigating Symptoms of Traumatic Brain Injury in Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 2019, 764–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl MG. Neurofeedback with PTSD and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). In: Restoring the Brain. Routledge; 2020: 256–284.

- Popa LL, Chira D, Strilciuc Ștefan, et al. Non-Invasive Systems Application in Traumatic Brain Injury Rehabilitation. Brain Sci 2023; 13. [CrossRef]

- White RD, Turner RP, Arnold N, et al. Treating Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Combining Neurofeedback and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in a Single Case Study. Clin EEG Neurosci 2022; 53: 519–531.

- Ortega MA, Fraile-Martinez O, García-Montero C, et al. A General Overview on the Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: Applications, Mechanisms and Translational Opportunities. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021; 57. [CrossRef]

- Englander J, Bushnik T, Duong TT, et al. Analyzing risk factors for late posttraumatic seizures: a prospective, multicenter investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003; 84: 365–373.

- Pitkänen, A.; Bolkvadze, T.; Immonen, R. Anti-epileptogenesis in rodent post-traumatic epilepsy models. Neurosci Lett 2011, 497, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnigan SP, Walsh M, Rose SE, et al. Quantitative EEG indices of sub-acute ischaemic stroke correlate with clinical outcomes. Clin Neurophysiol 2007; 118: 2525–2532.

- Marzbani, H.; Marateb, H.R.; Mansourian, M. Neurofeedback: A Comprehensive Review on System Design, Methodology and Clinical Applications. Basic Clin Neurosci 2016, 7, 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sitaram R, Ros T, Stoeckel L, et al. Closed-loop brain training: the science of neurofeedback. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2016; 18: 86–100.

- EEG neurofeedback research: A fertile ground for psychiatry? L’Encéphale 2019, 45, 245–255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinnler H, Tognoni G, Gruppo italiano per lo studio neuropsicologico dell’invecchiamento. Standardizzazione e taratura italiana di test neuropsicologic. 1987.

- Carlesimo GA, De Risi M, Monaco M, et al. Normative data for measuring performance change on parallel forms of a 15-word list recall test. Neurol Sci 2014; 35: 663–668.

- Carlesimo, G.A.; Caltagirone, C.; Gainotti, G. The Mental Deterioration Battery: normative data, diagnostic reliability and qualitative analyses of cognitive impairment. The Group for the Standardization of the Mental Deterioration Battery. Eur Neurol 1996, 36, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini A, Grossi D, Capitani E, et al. Verbal and spatial immediate memory span: normative data from 1355 adults and 1112 children. Ital J Neurol Sci 1987; 8: 539–548.

- Novelli G, Papagno C, Capitani E, et al. Tre test clinici di ricerca e produzione lessicale. Taratura su sogetti normali. Archivio di Psicologia, Neurologia e Psichiatria 1986; 47: 477–506.

- Novelli C, Papagno C, Capitani E, et al. Tre test clinici di memoria verbale a lungo termine: Taratura su soggetti normali. Archivio di psicologia, neurologia e psichiatria 1986; 47: 278–296.

- Caffarra P, Vezzadini G, Dieci F, et al. Rey-Osterrieth complex figure: normative values in an Italian population sample. Neurol Sci 2002; 22: 443–447.

- Caffarra P, Vezzadini G, Dieci F, et al. Una versione abbreviata del test di Stroop: dati normativi nella popolazione italiana. NUOVA RIVISTA DI NEUROLOGIA 2002; 12: 111–115.

- Amato MP, Portaccio E, Goretti B, et al. The Rao’s Brief Repeatable Battery and Stroop test: normative values with age, education and gender corrections in an Italian population. Multiple Sclerosis Journal 2006. [CrossRef]

- Pedrabissi, L.; Santinello, M. Verifica della validità dello S.T.A.I. forma Y di Spielberger. BOLLETTINO DI PSICOLOGIA APPLICATA 1989, 191-192, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ghisi M, Flebus GB, Montano A, et al. Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition. Adattamento italiano: Manuale. ITA; 2006.

- Ros T, J Baars B, Lanius RA, et al. Tuning pathological brain oscillations with neurofeedback: a systems neuroscience framework. Front Hum Neurosci 2014; 8: 1008.

- Keller, I. Neurofeedback Therapy of Attention Deficits in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotherapy 2001, 5, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Ferrer A, Noreña D de, Serrano JI, et al. Cognitive rehabilitation in a case of traumatic brain injury using EEG-based neurofeedback in comparison to conventional methods. J Integr Neurosci 2021; 20: 449–457.

- Vilou I, Varka A, Parisis D, et al. EEG-Neurofeedback as a Potential Therapeutic Approach for Cognitive Deficits in Patients with Dementia, Multiple Sclerosis, Stroke and Traumatic Brain Injury. Life (Basel) 2023; 13. [CrossRef]

- Thibault, R.T.; Lifshitz, M.; Raz, A. The self-regulating brain and neurofeedback: Experimental science and clinical promise. Cortex 2016, 74, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, B.C.; Flashman, L.A.; Saykin, A.J. Executive dysfunction following traumatic brain injury: neural substrates and treatment strategies. NeuroRehabilitation 2002, 17, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng Z, Zhao X, Cui X, et al. Subtle Pathophysiological Changes in Working Memory-Related Potentials and Intrinsic Theta Power in Community-Dwelling Older Adults With Subjective Cognitive Decline. Innov Aging 2023; 7: igad004.

- Sibilano E, Brunetti A, Buongiorno D, et al. An attention-based deep learning approach for the classification of subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment using resting-state EEG. J Neural Eng 2023; 20. [CrossRef]

- Wang S-Y, Lin I-M, Fan S-Y, et al. The effects of alpha asymmetry and high-beta down-training neurofeedback for patients with the major depressive disorder and anxiety symptoms. J Affect Disord 2019; 257: 287–296.

- Walker, J.E.; Kozlowski, G.P. Neurofeedback treatment of epilepsy. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2005, 14, 163–176, viii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson AA, Densmore M, Frewen PA, et al. Homeostatic normalization of alpha brain rhythms within the default-mode network and reduced symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder following a randomized controlled trial of electroencephalogram neurofeedback. Brain Commun 2023; 5: fcad068.

- du Bois N, Bigirimana AD, Korik A, et al. Neurofeedback with low-cost, wearable electroencephalography (EEG) reduces symptoms in chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. J Affect Disord 2021; 295: 1319–1334.

- Leem J, Cheong MJ, Yoon S-H, et al. Neurofeedback self-regulating training in patients with Post traumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial study protocol. Integr Med Res 2020; 9: 100464.

- Corrigan, F.; Wee, I.C.; Collins-Praino, L.E. Chronic motor performance following different traumatic brain injury severity-A systematic review. Front Neurol 2023, 14, 1180353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).