Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Title: Impact of Pharmacist-led Intervention on Medication Adherence and Asthma Control in Asthmatic Patients Attending Respiratory Clinic at National Hospital Abuja. Background: Asthma is a widespread disease affecting more than 300 million people globally. Adherence to management protocols, both pharmacotherapy and non-drug therapy is key to positive treatment outcomes. Pharmacists with their professional knowledge and skills play a vital role in educating the patients to improve treatment adherence and clinical outcomes. This study aimed to assess the impact of Pharmacist-led intervention on medication adherence and asthma control. Objectives: To assess symptoms and medication use among asthmatic patients, estimate the sample prevalence of medication non-adherence and its causes and evaluate the outcome of Pharmacist-led intervention on medication adherence and asthma control. Methods: It was a pre/post – interventional study carried out at the Medical Outpatient Clinic among 49 consented patients with primary diagnosis of asthma. Purposive sampling was used. Participants received targeted pharmacist-led intervention in form of asthma education, medication adherence counseling, how to use inhaler devices correctly and were monitored via mobile phone post-intervention. Descriptive statistics was used to summarise data. Chi square test was used to compare categorical variables while Wilcoxon signed rank and McNemar tests were used to compare differences in medication adherence and asthma control. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Results: Majority of the patients were females (32; (65.3%)) and had family history of asthma (30; (61.2%)). Cough was the major symptom experienced before diagnosis (31; (35.2%)). Asthma exacerbations were more frequent in cold weather (35; (76.1%)), dust was the most common trigger (27; (34.2%)). Salbutamol inhaler was the commonly used asthma medication (31; (39.3%)). Pre intervention, most of the patients showed poor (21; (42.9%)) to medium adherence (26; (53.1%)) while 2 (4.1%) showed good adherence. Forgetfulness (17; (73.9%)), daily/continuous use of medication (18; (81.8%)) and use of herbal remedies (15; (68.2%)) were reasons for non-adherence (p<0.05). 44 (95.7%) patients were uncontrolled pre intervention. Post-intervention, patients with good adherence increased to 32, (76.2%) (p <0.05), the number of patients with controlled asthma increased to 25, (59.5%) (p<0.001). Conclusions: Pharmacist-led intervention improved medication adherence and symptoms control in asthmatic patients.

Keywords:

1. Background of the Study

Objectives

- i.

- Assess experience of signs and symptoms of asthma among asthmatic patients receiving care at Respiratory Clinic at National Hospital Abuja

- ii.

- Assess medication use among asthmatic patients receiving care at Respiratory Clinic at National Hospital Abuja

- iii.

- Determine the prevalence of medication non-adherence among asthmatic patients receiving care at Respiratory Clinic at National Hospital Abuja.

- iv.

- Identify the causes of medication non-adherence among asthmatic patients receiving care at Respiratory Clinic at National Hospital Abuja.

- v.

- Evaluate the impact of Pharmacist-led intervention on medication adherence among asthmatic patients receiving care at Respiratory Clinic at National Hospital Abuja

- vi.

- Evaluate the impact of pharmacist-led intervention on symptoms control among asthmatic patients receiving care at Respiratory Clinic at National Hospital Abuja

2. Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Ethical Approval

2.3. Intervention Provided

3. Results

| Demographic Information | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 17(34.7) |

| Female |

32(65.3) |

| Age group (years) | |

| 15-29 | 13(26.5) |

| 30-44 | 19(38.8) |

| 45-59 | 11 (22.4) |

| 60-74 | 4 (8.2) |

| 75-89 Mean ± SD =37.31±16.43 |

2 (4.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 16 (32.7) |

| Married | 31 (63.3) |

| Divorced | 1 (2.0) |

| Widowed |

1 (2.0) |

| Occupation | |

| Self Employed | 18 (36.7) |

| Civil servant | 21 (42.9) |

| Housewife | 2 (4.1) |

| Student | 2(4.1) |

| Retiree | 6 (12.2) |

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| N(%) | |

| Symptoms experienced before diagnosis Cough Shortness of breath Wheezing Chest pain Others |

31 (35.2) 30 (34.1) 19 (21.6) 2 (2.3) 6 (6.6) |

| Family history of asthma Yes No |

30 (61.2) 19 (38.8) |

| Relationship with family member Father Mother Sibling Grandparent |

10 (28.6) 8 (22.9) 9 (25.7) 8 (22.9) |

| History of allergies triggering symptoms Yes No |

38 (84.4) 7 (15.6) |

| Specific allergies Dust Cold air Perfumes Smoke Others |

27 (34.2) 22 (27.8) 17 (21.5) 4 (5.1) 9 (11.4) |

| Statements | SA N (%) |

A N (%) |

D N (%) |

SD N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I experience more attacks during cold seasons/weather | 26 (56.5) | 9 (19.6) | 9 (19.6) | 2 (4.3) | |

| I experience an attack when frightened or after a shock | 8 (19.5) | 4 (9.8) | 22 (53.7) | 7 (17.1) | |

| My asthma symptom occurs after a particular food | 5 (12.8) | 4 (10.3) | 19 (48.7) | 11 (28.2) | |

| I get an attack after physical exertion | 8 (18.6) | 15 (34.9) | 16 (37.2) | 4 (9.3) | |

| I get an attack from excessive laughter | 5 (12.5) | 16 (40.0) | 11 (27.5) | 8 (20.0) | |

| I begin to experience asthma symptoms after smell of food cooking | 8 (19.0) | 11 (26.2) | 17 (40.5) | 6 (14.3) |

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| OTC/Prescribed Salbutamol inhaler *Seretide® inhaler Salbutamol tablets Montelukast®tablets +Symbicort® inhaler Loratadine tablets Bisoprolol tablets Prednisolone tablets |

31(39.3) 20(25.3) 16(20.3) 6(7.6) 3(3.8) 1(2.3) 1(2.3) 1(2.3) N=79 |

| at National Hospital Abuja | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherence | |||||||

| PreIntervention |

PostIntervention | ||||||

| Medication Adherence Question | Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Z | P value | |

| Do you ever forget to take your medicine? |

28 (57.1) | 21 (42.9) | 10 (23.8) | 32 (76.2) |

-3.357 |

0.001 |

|

| Are you not being careful at times about taking your medicine? |

20 (40.8) | 24 (49.0) | 9 (21.4) | 33 (78.6) |

-2.496 |

0.013 |

|

| Do you sometimes stop taking your medicines when you feel better? |

35 (72.9) | 13 (27.1) | 6 (14.3) | 36 (85.7) |

-4.6 |

0.001 |

|

| Do you sometimes stop taking your medicines if they make you feel worse? |

20 (40.8) | 25 (51.0) | 10 (23.8) | 32 (76.2) |

-2.673 |

0.008 |

|

| Outpatients Attending Respiratory Clinic at National Hospital Abuja | ||||||

| Variables |

Strongly agree N (%) |

Agree N (%) |

Disagree N (%) |

Strongly disagree N (%) |

50th percentile | P-Value |

| Concern about side effect(s) | 6 (27.3) | 9 (40.9) | 6 (27.3) | 1(4.5) | 1.00 | 0.360 |

| Cost of prescribed medications unaffordable |

4 (18.2) |

6 (27.3) |

10 (45.5) |

2 (9.1) |

2.00 |

0.234 |

| Forgetfulness |

6 (26.1) |

11 (47.8) |

5 (21.7) |

1 (4.3) |

3.00 |

0.003 ⃰ |

| Physician mode of approach during treatment |

2 (9.1) |

7 (31.8) |

10 (45.5) |

3(13.6) |

2.00 |

0.933 |

| Pharmacist mode of approach during medication delivery and counseling |

3 (13.6) |

5 (22.7) |

10 (45.5) |

4 (18.2) |

2.00 |

0.670 |

| Daily/continuous use of medication |

6 (27.3) |

12 (54.5) |

4 (18.2) |

0 (0.0) |

2.00 |

0.026⃰ |

| Complex dosage regimen |

3 (13.6) |

10 (45.5) |

4 (18.2) |

5 (22.7) |

1.00 |

0.040 ⃰ |

| Complicated technique of handling inhaler |

5 (22.7) |

8 (36.4) |

7 (31.8) |

2 (9.1) |

1.00 |

0.479 |

| Physical inability to use the inhaler |

4(18.2) |

8(36.4) |

6(27.3) |

4(18.2) |

1.00 |

0.788 |

| Use of multiple medications to control symptoms |

3(13.6) |

14(63.6) |

3(13.6) |

2(9.1) |

1.00 |

0.247 |

| Lack of understanding of reasons for taking medications |

2(9.1) |

9 (40.9) |

8(36.4) |

3(13.6) |

1.00 |

0.709 |

| Interference of regimen with lifestyle |

4 (18.2) |

11 (50.0) |

3 (13.6) |

4 (18.2) |

1.00 |

0.084 |

| Personal/religious beliefs |

2 (9.1) |

3 (13.6) |

11 (50.0) |

6 (27.3) |

1.00 |

0.617 |

| Belief in herbal remedies |

4(18.2) |

11 (50.0) |

4 (18.2) |

3 (13.6) |

1.00 |

0.037 ⃰ |

| Co-existing disease states |

4(18.2) |

9 (40.9) |

6 (27.3) |

2 (9.1) |

1.00 |

0.177 |

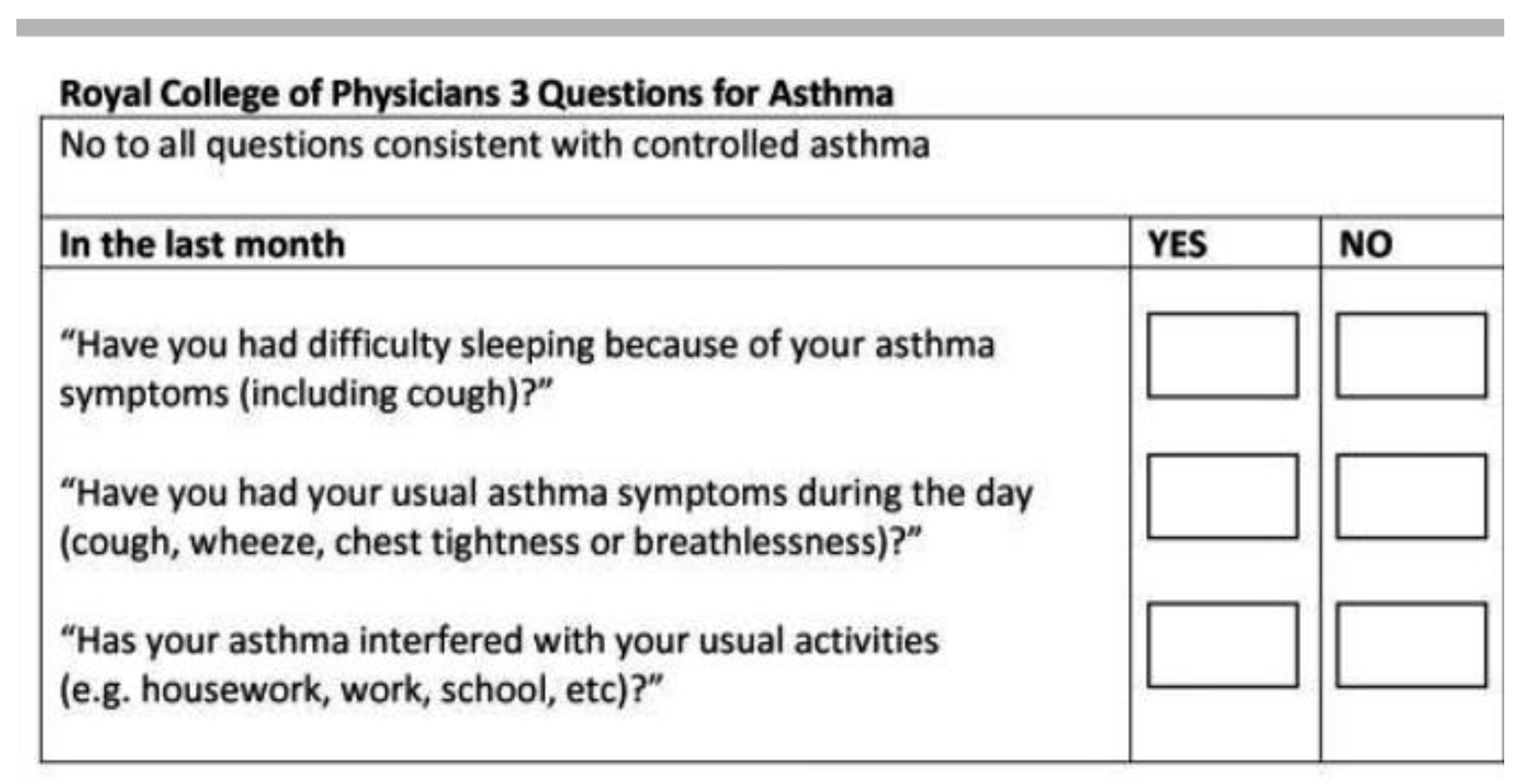

| Control of Asthma among Asthmatic Outpatients Attending Respiratory Clinic at National Hospital Abuja | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROYAL COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS QUESTIONS | N (%) | P-value | |||

| PRE-INTERVENTION | POST- INTERVENTION | ||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| Have you had difficulty in sleeping because of your asthma symptoms, especially coughing? |

41 (89.1) | 5 (10.9) | 9 (19.6) | 33 (71.7) | <0.001⃰ |

| Have you had your usual asthma symptoms during the day? (coughing, wheeze, or breathlessness) |

39 (84.8) | 7 (15.2) | 15 (32.6) | 27 (58.7) | 0.001⃰ |

| Has your asthma interfered with your usual routine activities Uncontrolled Controlled |

31 (67.4) 44 (95.7) 2 (4.3) |

13 (28.2) 2 (4.3) 44 (95.7) |

11 (26.2) 17 (36.9) 25 (54.3) |

31 (73.8) 25 (54.3) 17 (36.9) |

<0.001⃰ <0.001⃰ <0.001⃰ |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

Appendix B

- 1.

-

How long have you been diagnosed with asthma?1-5 years ( ) 6-10 years ( ) 11-15 years ( )

- 2.

-

Where were you first diagnosed?General hospital ( ) Teaching hospital ( )Private hospital ( ) Traditional practitioner ( )

- 3.

-

What were the initial signs/symptoms that you experienced before the diagnosis?Cough ( ) Shortness of breath ( )Wheezing ( ) Others, please specify ___________________________

- 4.

-

Any family history of asthma?Yes ( ) No ( )

- 5.

-

If yes, what is the relationship?Father ( ) Mother ( ) Sibling ( ) Grandparents ( )Others, please specify _________________________

- 6.

-

Any history of allergy that trigger the symptoms?Yes ( ) No ( )

- 7.

-

If yes, what are those allergies?Cold air ( ) perfumes ( ) dust ( ) Others, please specify _____________________

- 8.

-

What are the triggering signs/symptoms before you experience an attack?Breathlessness ( ) cough ( ) others, please specify_____________

- 9.

-

Please indicate your opinion to the statements as it applies to you.SA= Strongly agree A= Agree D= Disagree SD= Strongly disagree

| Statements | SA | A | D | SD |

| I experience more attacks during cold season/weather | ||||

| I experience an attack when frightened or after a shock | ||||

| My asthma symptom occur after a particular food | ||||

| I get an attack after physical exertion | ||||

| I get an attack from excessive laughter | ||||

| I begin to experience asthma symptoms after smell of food cooking |

- 10.

-

What are the present complaints that made you come to see the doctor?________________________________________________________________

- 11.

-

What prescribed and over-the-counter (OTC) medications are you taking presently? (investigator might crosscheck with the patient). Salbutamol tablets ( )Salbutamol inhaler ( ) Seretide inhaler ( ) others, please specify________________________________________________________________

- 12.

- Have you ever discontinued any of your prescribed (controller/relief) medications? Yes ( ) No ( )

- 13.

-

If yes, could you mention the specific medications discontinued?________________________________________________________________

- 14.

-

Could you indicate the reasons why you discontinued the medication(s)?Physician discontinued the drug ( ) Cost unaffordable ( )Intolerable side effects ( ) Complex dose regimen ( )Others, please specify ____________________________________________

- 15.

-

If side effect is the reason for discontinuation, could you please describe the effect?________________________________________________________________

- 16.

-

Aside medications, what other treatment modalities were recommended by your doctor?Dust avoidance ( ) Animal avoidance ( ) Hygiene ( )Others, please specify ________________________________________________

- 17.

-

Have you ever used any herbal remedies in the past for the asthma condition?Yes ( ) No ( )

- 18.

- If yes, mention the specific herbal medicine used. _____________________________

- 19.

-

Do you find herbal medicines useful?Yes ( ) No ( )

- 20.

-

If yes, do your herbs help to bring quick relief?Yes ( ) No ( )

- 21.

- What herbal medicine(s) do you use in the management of your asthma?

- 22.

-

Do you ever forget to take your prescription medicine? Yes ( )No ( )

- 23.

-

Are you not been careful at times about taking your medicine?Yes ( ) No ( )

- 24.

-

Do you sometimes stop taking your medicine when you feel better?Yes ( ) No ( )⠀

- 25.

-

Do you sometimes stop taking your medicine if they make you feel worse?Yes ( ) No ( )

- 26.

-

Below are likely reasons for treatment non-adherence among patients. Please indicate your opinion to these as it applies to you.SA= Strongly agree A= Agree D= Disagree SD= Strongly disagree

| General reasons | SA | A | D | SD |

| Concern about side effects | ||||

| Cost of prescribed medications unaffordable | ||||

| Forgetfulness | ||||

| Physician mode of approach during treatment | ||||

| Pharmacist mode of approach during medication delivery and counseling | ||||

| Daily/continuous use of medication | ||||

| Complex dosage regimen | ||||

| Complicated technique of handling inhaler | ||||

| Physical inability to use the inhaler | ||||

| Use of multiple medications to control symptoms | ||||

| Lack of understanding of reasons for taking medications | ||||

| Interference of regimen with lifestyle | ||||

| Personal/religious beliefs | ||||

| Belief in herbal remedies | ||||

| Co-existing disease states |

- 27.

- Have you had difficulty in sleeping because of your asthma symptoms, especially coughing? Yes ( ) No ( )

- 28.

-

Have you had your usual asthma symptoms during the day (cough, wheeze or breathlessness)?Yes ( ) No ( )

- 29.

- Has your asthma interfered with your usual routine activities? Yes ( ) No ( )

Appendix C

Appendix D

- ➢

- BASIC FACTS ABOUT ASTHMA

- •

- Contrast normal and asthmatic airways

- ➢

- ROLES OF MEDICATIONS

- •

- Long term control and Quick relief medications

- ➢

- SKILLS IN DEVICES HANDLING

- •

- Inhalers, spacers, symptom and peak flow monitoring; early warning signs of attack

- ➢

- RELEVANT ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL MEASURES

- •

- WHEN AND HOW TO TAKE RESCUE ACTIONS

APPENDIX E

References

- Adisa R, Akanji I.O, FakeyeT.O. (2017). Medication use, adherence and asthma control in ambulatory patients attending the chest clinic of a tertiary facility in southwestern Nigeria. West African Journal of Pharmacy, 28(1):1-14.

- Akhiwu H.O, Asani M.O, Johnson A.B and Ibrahim M. (2016). Epidemiology of paediatric asthma in a Nigerian population. Journal of Health Research Review,2017(4):130-6.

- American College of Preventive Medicine Medication Adherence Clinical Reference. (2011). www.acpm.org/?MedAdherTT_ClinRef.Accessed June 10, 2020.

- Amin S. (2020).Usage patterns of short-acting β2-Agonists and inhaled corticosteroids in asthma: a targeted literature review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;8(8):2556–2564. e8.

- Baird C, Lovell J, Johnson M, Shiell K, Ibrahim JE. (2017). The impact of cognitive impairment on self management in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review.Respiratory Medicine,(129):130-139.

- Bauman, A., et al., (2005). Asthma adherence: A guide for Health Professionals. What we mean by adherence. [Online]. Australia: National Asthma Council. Available from: http//www.nationalasthma.org.au/health-professionals/asthma-adherence pdf. (Accessed: 12th September, 2015).

- Belachew S.A, Erku D.A, Yimenu D.K, Gebresillasie B.M, (2018). Assessment of predictors for acute asthma attack in asthmatic patients visiting an Ethiopian hospital: are the potential factors still a threat? E Collection 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bender B.G, Bender S.E (2005). Patient identified barriers to asthma treatment adherence: responses to interviews, focus groups and questionnaires. Immunology and Allergy Clinics of North America, (25):107-130.

- Benedicte L; Jordi S; Raquel G; Cecilie S; Deborah J. et al., (2012). Gender differences in Prevalence, diagnosis and Incidence of Allergic snd non-Allergic asthma: a population- based cohort.British Medical Journal,(67)7.

- British Guideline on the Management of Asthma (2012). British Thoracic Society.

- Brocklebank D., Ram F., Wright J., Barry P., Cates C., Davies L., et al., (2001). Comparison of the effectiveness of inhaler devices in asthma and chronic obstructive airways disease: A systematic review of the literature. Health Technology Assessment, 5 (26):1-149. [CrossRef]

- Bush A, Menzies-Gow A; Menzies-Gow (2009). "Phenotypic differences between pediatric and adult asthma". American Thoracic Society. 6 (8): 712–9. [CrossRef]

- Chotirmall S.H, Watts M, Branagan P, Donegan C.F, Moore A, McElvaney N.G.(2009). Diagnosis and management of asthma in older adults.Journal of American Geriatric Society, (57):901–9.

- Cutler R.L, Fernandez-Llimos F, Frommer M, Benrimoj C, Garcia-Cardenas V. (2018). Economic impact of medication non-adherence by disease groups: a systematic review. British Medical Journal,8(1):e016982.

- Desalu, O.O., Oluboyo, P.O., Salami, A.K. (2009). The Prevalence of Bronchial Asthma among Adults in Ilorin, Nigeria.African Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences,38(2): 149-154.

- Farhat A, Abou-Karroum R, Panchaud A, Csajka C, Al-Hajje A. Impact of Pharmaceutical Interventions in Hospitalized Patients: A Comparative Study Between Clinical Pharmacists and an Explicit Criteria-Based Tool. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2021 Oct 28;95:100650. PMID: 34824649; PMCID: PMC8604771. [CrossRef]

- Global Asthma Network. The Global Asthma Report 2018. Available: http://globalasthmareport.org/resources/Global_Asthma_Report_2018.pdf. Accessed: 28 April 2021.

- Global Health Estimates ( 2016). Disease burden by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2016.Geneva, World Health Organization; 2018.

- Global Initiative for Asthma.(GINA, 2019).Global strategy for asthma management and prevention.www.ginasthma.org. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Global Initiative for Asthma.(GINA, 2020).Global strategy for asthma management and prevention.www.ginasthma.org. Accessed February 8, 2021.

- Global Initiative for Asthma.(GINA, 2022).Global strategy for asthma management and prevention.www.ginasthma.org. Accessed June 12, 2023.

- Herndon J.B, Mattke S, Evans Cuellar A, et al.( 2012). Anti-inflammatory medication adherence, healthcare utilization and expenditures among Medicaid and children’s health insurance program enrollees with asthma. Pharmacoeconomics, (30): 397–412.

- Hsu Y.N, Fang C.L, Lou Y.J, Chen L.C. (2018). Efficacy of Pharmacist Intervention and Health Education in asthma control.European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy, Science and Practice, suppl. Supplement 1; London,(25): A138. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim M,Verma R, Garcia-Contreras L.( 2015). Inhalation drug delivery devices: technology update. Med Devices(Auckland),8:131-139. [CrossRef]

- dani E., Raji H., Madadizadeh F. et al., (2019). Prevalence of asthma and other allergic conditions in adults in Khuzestan, southwest Iran, 2018.Biomedical Central Journal of Public Health,( 19) 303. [CrossRef]

- Iuga A.O, McGuire M.J. (2014). Adherence and Healthcare Costs. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 7:35-44.

- Jeminiwa R, Hohmann L, Qian J, et al. (2019). Impact of eHealth on medication adherence among patients with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2019;149:59–68. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan A and Price D. (2018). Matching inhaler devices with patients: the role of the primary care Physician. Canadian Respiratory Journal, (94)7:30-51. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Combs K, Downs J, Tillman F. (2018). Medication Adherence: The Elephant in the Room. United States Pharmacist,43(1) 30-34.

- Koda-Kimble MA. (2009). Vol. 23. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. Applied therapeutics: The clinical use of drugs; pp. 1–43.

- Makhinova T, Barner CJ, Richards KM,Rascati KL; (2015). Asthma Controller Medication Adherence, Risk of Exacerbation, and Use of Rescue Agents among Texans.Journal of Managed Care Specialty Pharmacy, 21(12):1124-32. [CrossRef]

- Masoli, M., Fabian, D., Holt, S., Beasley, R. (2004). Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Program. The global burden of asthma: Executive summary of the GINA Disssemination Committee report. Allergy,(59):469-78.

- Mehuys E, Van Bortel L, Van Tongelen I, Annemans L, Remon J.P, Brusselle G (2008). European Respiratory Journal,(31):790-799. [CrossRef]

- Melani A.S, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, et al., (2011). Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respiratory Medicine,105(6):930-938. [CrossRef]

- Mes M.A, Katzer C.B, Chan A.H.Y, et al. Pharmacists and medication adherence in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(2):1800485. [CrossRef]

- Morton RW, Elphick HE, Craven V, Shields MD and Kennedy L (2020) Aerosol Therapy in Asthma–Why We Are Failing Our Patients and How We Can Do Better. Frontiers in Pediatrics,(8):305. [CrossRef]

- Morisky DE, Green LW and Levine DM. (1986). Concurrent and Predictive validity of a self- reported measure of medication adherence. Medical care(24):67-74.

- Nannini L, Poole P, Milan SJ, Kesterton A. (2013). Combined Corticosteroid and long acting β- agonist in one inhaler versus inhaled corticosteroid alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Systematic Review,(8):CD006826.

- Omole, M.K and Ilesanmi, N.A . (2010). Patient Medication Knowledge Governing Adherence to Asthma Pharmacotherapy: A Survey in Rural Lagos, Nigeria. Nigeria. African Journal of Biomedical and Respiratory Medicine,93 – 98. www.ajbrui.net.

- Ozoh O, Aderibigbe, S.A., Ayuk A.C, Desalu O.E, Oridota. O.O, Olufemi O., et,al.,(2019). The prevalence of asthma and allergic rhinitis in Nigeria: A nationwide survey among children, adolescents and adults. PLOS One. [CrossRef]

- Pearson MG, Bucknall C: (1999). Measuring Clinical Outcome in Asthma: A Patient-focused Approach.Clinical Effectiveness & Evaluation Unit, Royal College of Physicians.

- Ponnusankar S, Surulivelrajan M, Anandamoorthy N, Suresh B. (2004). Assessment of impact of medication counseling on patients’ medication knowledge and compliance in an outpatient clinic in South India. Patient Education Counseling 2004; 54: 55-60.

- Rafeeq M.M and Murad H.A.S. (2017). Evaluation of drug utilization pattern for patients of bronchial asthma in a government hospital in Saudi Arabia.Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice,(20)9:1098-1105.

- Rene-Henri N, Khamla Y, Nadaira N, Ouellet C, Blais L, Lalonde L, et al., (2009). Community pharmacists’ interventions in asthma care: a descriptive study. Annals of Pharmacotherapy,(43):104–111.

- Sandzzi A, Balbo P, Candoli P, et al.,(2014). COPD: adherence to therapy. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine, 9(1):60. [CrossRef]

- Sayadeda K, Ansari N.A, Ahmed Q.S, Upadhyay P, Dey P.S,Madwhar (2013). A Drug utilization study of antiasthmatic drugs in paediatric age group in a tertiary care teaching hospital, Bareily, UP-India. International Journal of University of Pharmaceutical Biosciences, (2):353-60.

- Thamby S.A, Juling P, Xin B.T.W, Jing N.C (2012). Retrospective studies on drug utilization patterns of asthmatics in a Government hospital in Kedah, Malaysia. International Current Pharmaceutical Journal,(1):353-60.

- The Global Asthma report.(2018). The International union against Tuberculosis and Lung disease, 201 201. Available from: http//www.globalasthmareport.org/sites/default/files/Global-Asthma-Report-201 pdf (Accessed: 6th March, 2018).

- Usmani O.S, Lavorini F, Marshall J, et al., (2018).Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respiratory Resource.19:1(10). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2003). Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action URL: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdf Retrieved July 2022.

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2020. Report on chronic respiratory Diseases. Retrieved July, 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).