Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

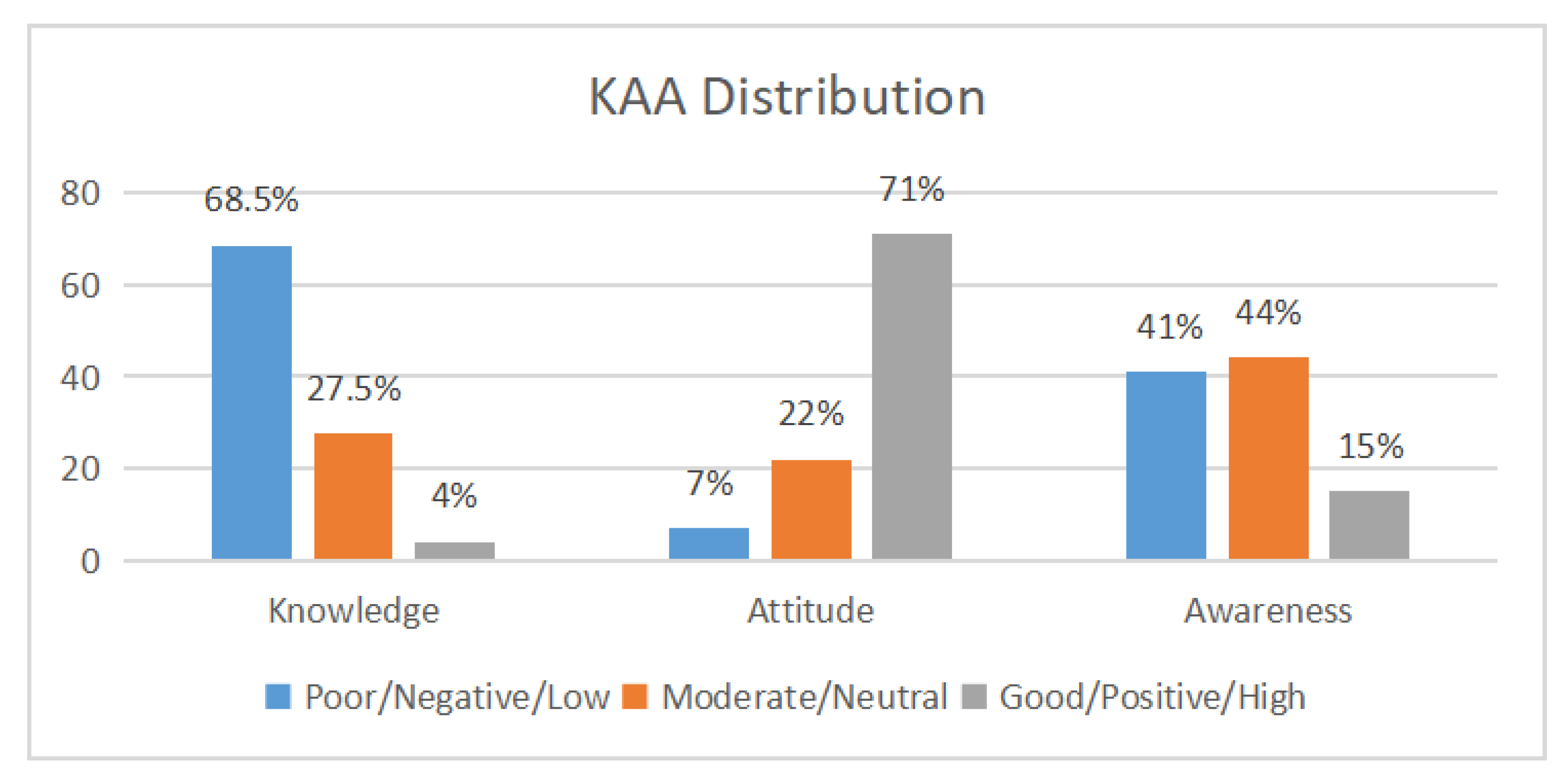

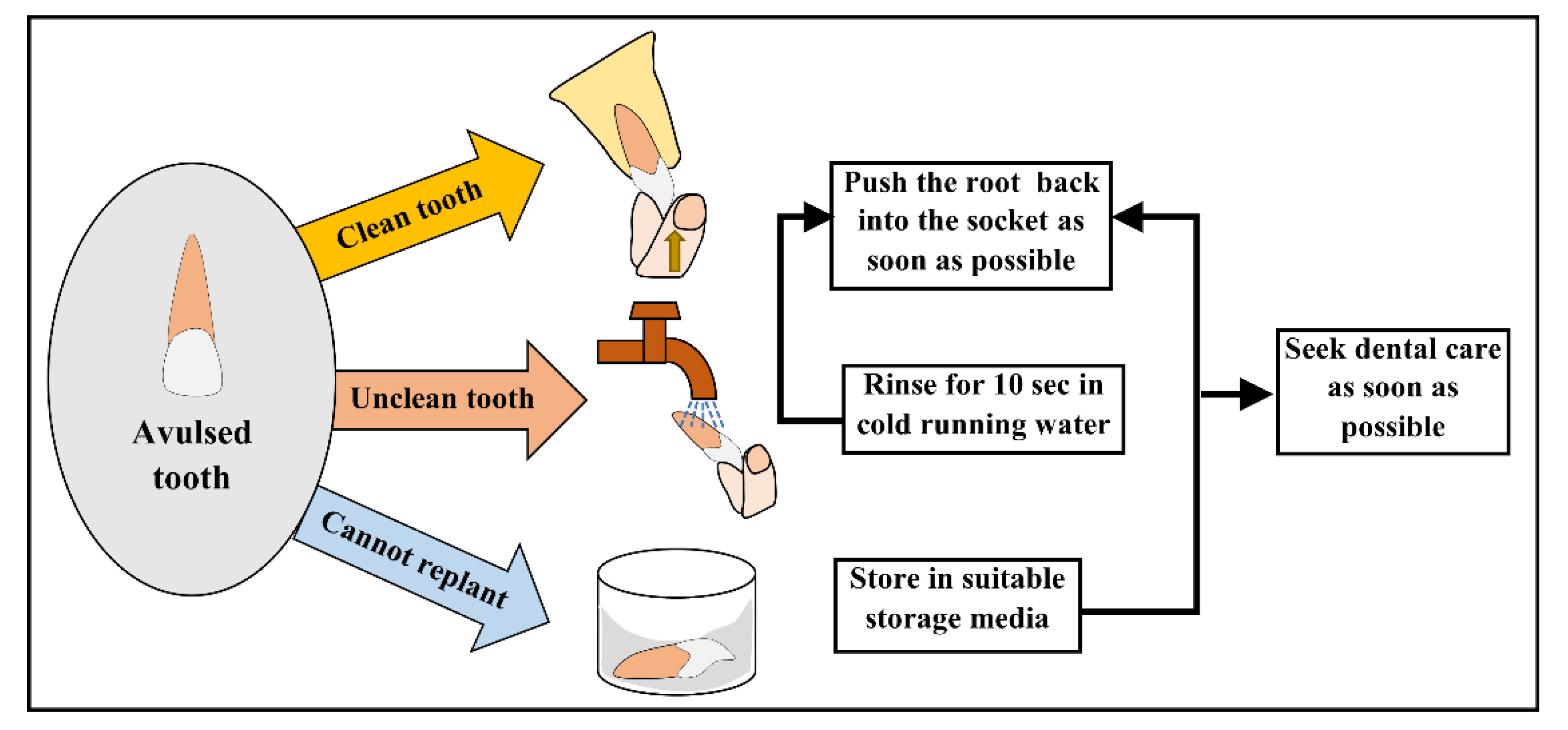

Background/Objectives: Traumatic dental injuries (TDIs) are common in adolescents and require immediate first aid to optimize outcomes, especially in cases of avulsion. Adolescents are often the first responders during school or sports activities, yet their preparedness remains unclear. This study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitude, and awareness of pre-university students in Mangalore, Karnataka, regarding the emergency management of TDIs. Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional survey was conducted among 400 adolescents aged 15 to 18 years from four randomly selected pre-university colleges. A structured, validated 20-item questionnaire assessed demographic characteristics and domains of knowledge (6 items), attitude (4 items), and awareness (6 items). Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and one-way ANOVA. Results: Knowledge regarding dental trauma management was low, with a mean score of 2.19 ± 1.28 out of 6; only 26.3% knew that avulsed permanent teeth can be replanted and 7% identified an appropriate storage medium. Attitudes were positive, with 88.8% of the participants expressing willingness to assist an injured peer. Awareness related to preventive practices and prior exposure was moderate; mouthguard use was reported by only 11.5% of students. Knowledge scores did not differ significantly across schools (p > 0.05). Conclusions: Adolescents demonstrated favorable attitudes but inadequate knowledge of essential emergency procedures for TDIs. School-based dental first-aid training and reinforcement of preventive practices are urgently needed to improve adolescents’ preparedness for managing dental trauma.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Study Design and Setting

2.3. Sample Size Determination

2.4. Participants: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Questionnaire Development

2.6. Validation and Pilot Testing

2.7. Data Collection Procedure

2.8. Bias Control

2.9. Scoring of Knowledge, Attitude, and Awareness

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Awareness Related to Dental Trauma

3.3. Attitude Toward Emergency Management

3.4. Knowledge Regarding Emergency Management of Dental Trauma

3.5. Comparison of Knowledge Scores Between Schools

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TDIs | Traumatic dental injuries |

| IADT | International Association of Dental Traumatology |

| KAA | Knowledge–Attitude–Awareness |

| HBSS | Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution |

| CSM | custom-made mouthguards |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

References

- Krishna, M. H. Malur, D. V. Swapna, S. Benjamin, and C. A. Deepak, “Traumatic Dental Injury—An Enigma for Adolescents: A Series of Case Reports,” Case Rep Dent, vol. 2012, pp. 1–5, 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. V. Saikiran, D. Gurunathan, S. Nuvvula, R. K. Jadadoddi, R. H. Kumar, and U. C. Birapu, “Prevalence of Dental Trauma and Their Relationship to Risk Factors among 8-15-Year-Old School Children,” Int J Dent, vol. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Hashim, H. Alhammadi, S. Varma, and A. Luke, “Traumatic Dental Injuries among 12-Year-Old Schoolchildren in the United Arab Emirates,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 20, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Kaul et al., “Prevalence and attributes of traumatic dental injuries to anterior teeth among school going children of Kolkata, India,” Med J Armed Forces India, vol. 79, no. 5, pp. 572–579, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang et al., “Dental trauma in children: monitoring, management, and challenges—a narrative review,” Jul. 31, 2025, AME Publishing Company. [CrossRef]

- L. G. H. de Lima, C. S. dos Santos, J. S. Rocha, O. Tanaka, E. A. R. Rosa, and G. G. Gasparello, “Comparative analysis of dental trauma in contact and non-contact sports: A systematic review,” Oct. 01, 2024, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Pithon, R. L. dos Santos, P. H. B. Magalhães, and R. S. da Coqueiro, “Brazilian primary school teachers’ knowledge about immediate management of dental trauma,” Dental Press J Orthod, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 110–115, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. Alyahya, S. A. Alkandari, S. Alajmi, and A. Alyahya, “Knowledge and Sociodemographic Determinants of Emergency Management of Dental Avulsion among Parents in Kuwait: A Cross-Sectional Study,” Medical Principles and Practice, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 55–60, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Abu-Dawoud, B. Al-Enezi, and L. Andersson, “Knowledge of emergency management of avulsed teeth among young physicians and dentists,” Dental Traumatology, vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 348–355, Dec. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. Tian, J. J. J. Lim, F. K. C. Moh, A. Siddiqi, J. Zachar, and S. Zafar, “Parental and training coaches’ knowledge and attitude towards dental trauma management of children,” Aust Dent J, vol. 67, no. S1, pp. S31–S40, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Young, K. Y. Wong, and L. K. Cheung, “Effectiveness of educational poster on knowledge of emergency management of dental trauma - Part 2: Cluster randomised controlled trial for secondary school students,” PLoS One, vol. 9, no. 8, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Kundu, S. Tandon, S. Chand, and A. Jaggi, “Assessing the Prevalence of Traumatic Dental Injuries and its Impact on Self-esteem among Schoolchildren in a Village in Gurugram,” Journal of Indian Association of Public Health Dentistry, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 294–299, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Maganur et al., “Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior toward Dental Trauma among Parents of Primary Schoolchildren Visiting College of Dentistry, Jizan,” Int J Clin Pediatr Dent, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 1030–1034, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dhindsa, “Knowledge regarding avulsion, reimplantation and mouthguards in high school children: Organised sports-related orodental injuries,” J Family Med Prim Care, vol. 8, no. 11, p. 3706, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Hegde, K. N. Pradeep Kumar, and E. Varghese, “Knowledge of dental trauma among mothers in Mangalore,” Dental Traumatology, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 417–421, 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Shenoy et al., “Evaluation of Knowledge, Awareness, and Attitude Towards Management of Displaced Tooth from Socket (Avulsion) Amongst Nursing Fraternity in Mangaluru City: A Cross-Sectional Study,” Journal of Health and Allied Sciences NU, vol. 14, no. S 01, pp. S120–S122, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Fouad et al., “International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 2. Avulsion of permanent teeth,” Aug. 01, 2020, Blackwell Munksgaard. [CrossRef]

- S. Avgerinos et al., “Position Statement and Recommendations for Custom-Made Sport Mouthguards,” Jun. 01, 2025, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- P. R. H. Newsome, D. C. Tran, and M. S. Cooke, “The role of the mouthguard in the prevention of sports-related dental injuries: A review,” 2001. [CrossRef]

- R. Biagi, C. R. Biagi, C. Mirelli, R. Ventimiglia, and S. Ceraulo, “Traumatic Dental Injuries: Prevalence, First Aid, and Mouthguard Use in a Sample of Italian Kickboxing Athletes,” Dent J (Basel), vol. 12, no. 10, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Tewari et al., “The International Association of Dental Traumatology (IADT) and the Academy for Sports Dentistry (ASD) guidelines for prevention of traumatic dental injuries: Part 10: First aid education,” Feb. 01, 2024, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- W. de A. Vieira et al., “Prevalence of dental trauma in Brazilian children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” 2021, Fundacao Oswaldo Cruz. [CrossRef]

- L. Roskamp et al., “Retrospective analysis of survival of avulsed and replanted permanent teeth according to 2012 or 2020 IADT Guidelines,” Braz Dent J, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 122–128, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Alsadhan, N. F. Alsayari, and M. F. Abuabat, “Teachers’ knowledge concerning dental trauma and its management in primary schools in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia,” Int Dent J, vol. 68, no. 5, pp. 306–313, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Aminu, K. K. Kanmodi, J. Amzat, A. A. Salami, and P. Uwambaye, “School-Based Interventions on Dental Trauma: A Scoping Review of Empirical Evidence,” , 2023, MDPI. 01 May. [CrossRef]

- Y. Berlin-Broner and L. Levin, “Enhancing, Targeting, and Improving Dental Trauma Education: Engaging Generations Y and Z,” Feb. 01, 2025, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- M. Nowosielska, J. Bagińska, A. Kobus, and A. Kierklo, “How to Educate the Public about Dental Trauma—A Scoping Review,” Feb. 01, 2022, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhong and P. Zheng, “Influence of children’s dental trauma education from community dentists on the cognitive level of children and parents,” Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 99–110, Jul. 2025. [CrossRef]

| Variables | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Q1. Age (Years) | 15 | 5 (1.3%) |

| 16 | 128 (32%) | |

| 17 | 231 (57.8%) | |

| 18 | 36 (9%) | |

| Q2. Gender | Male | 211 (52.8%) |

| Female | 189 (47.3%) | |

| Q3. Education | Class XI | 60 (15%) |

| Class XII | 340(85%) | |

| Q4. Stream | Arts | 26 (6.5%) |

| Science | 72 (18%) | |

| Commerce | 302 (75%) |

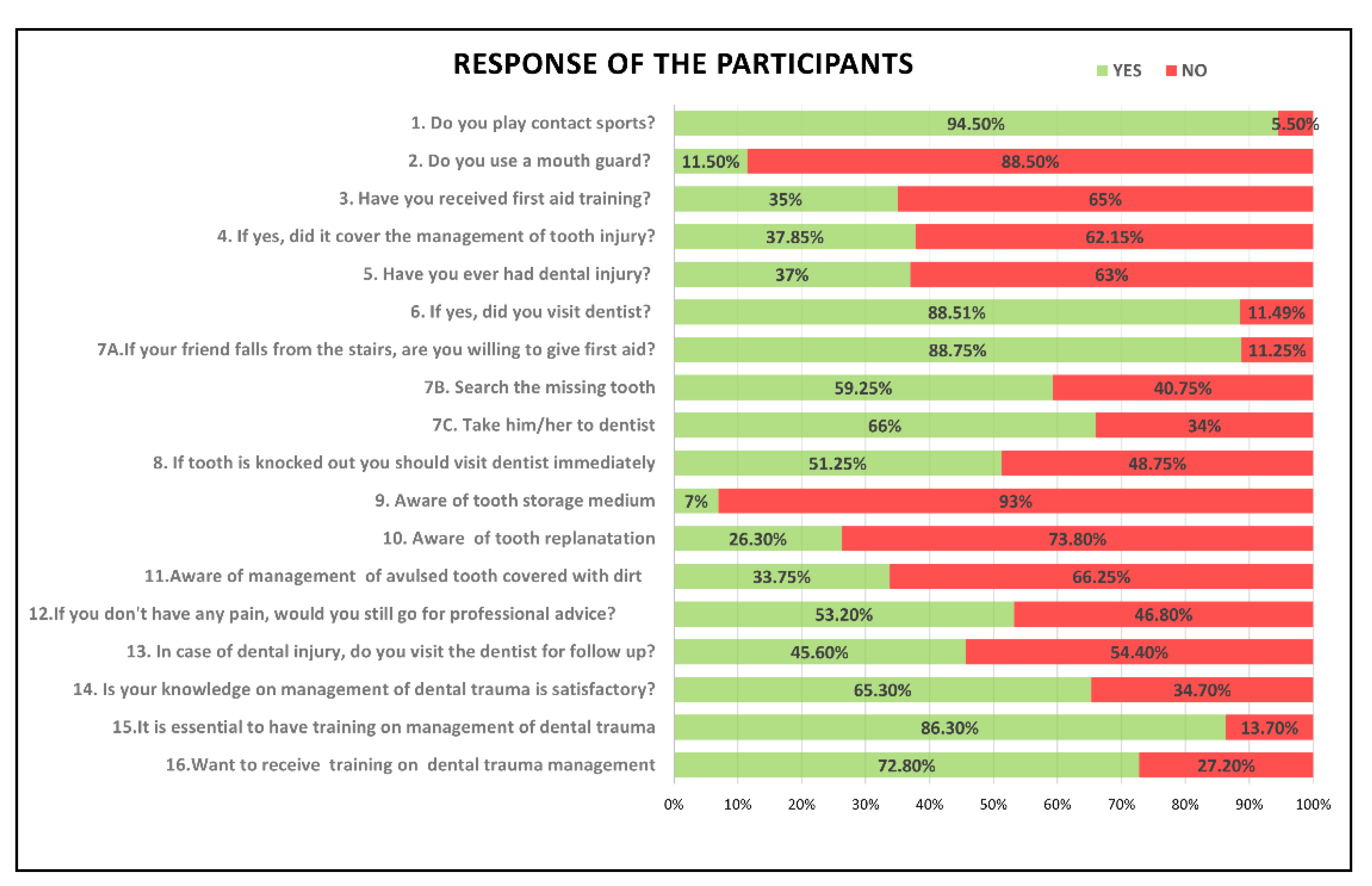

| Sl no. | Awareness Questions | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q5. | Do you play contact sports? | 378 (94.5%) | 22(5.5%) |

| Q6. | Do you use a mouth guard? | 46 (11.5%) | 354(88.5%) |

| Q7. | Have you received first aid training? | 140 (35%) | 260(65%) |

| Q8. | If yes, did it cover the management of tooth injury? (N=140) | 53 (37.85%) | 87(62.15%) |

| Q9. | Have you ever had dental injury? | 148 (37%) | 252(63%) |

| Q10. | If yes did you visit dentist? (N=148) | 131(88.51%) | 17(11.49%) |

| Sl no. | Attitude Questions | Yes | No |

| Q11. | During school hours, your classmate falls from the stairs. Would you like to look for any injury in the body and give first aid? | 355 (88.75%) |

45 (11.25%) |

| Q12. | If you notice that the front tooth is missing, would you search for the tooth immediately? | 237(59.25%) | 163 (40.75%) |

| Q13. | Should you take him/her to dentist? | 264 (66%) | 136 (34%) |

| Q14. | Would you like to attend an educational program on management of dental trauma? | 291 (72.8%) | 109 (27.2%) |

| Sl No. | Knowledge Questions | Correct (%) | Incorrect (%) |

| Q15. | Search for the lost tooth | 237(59.25%) | 163 (40.75%) |

| Q16. | Visit to the dentist | 264 (66%) | 136 (44%) |

| Q17. | Ideal time for the treatment | 205 (51.2%) | 195 (48.75%) |

| Q18. | An avulsed permanent tooth can be replanted | 105 (26.3%) | 205 (73.80%) |

| Q19. | Management of avulsed tooth covered with dirt. | 135 (34.75%) | 265(66.25%) |

| Q20. | Storage medium | 28 (7%) | 372 (93%) |

| School | Mean±SD | Mode | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.98±1.25 | 3 | 0.18 | |

| 2.24±1.41 | 1 | ||

| 2.37±1.24 | 3 | ||

| 2.16±1.21 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).