1. Introduction

ST-segment elevation on the electrocardiogram (ECG) is typically interpreted as a marker of acute coronary artery occlusion, prompting rapid activation of reperfusion pathways. However, a variety of non-ischemic conditions may mimic ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), leading to diagnostic uncertainty and potentially inappropriate interventions. Among extracardiac etiologies, gastrointestinal distension and mechanical small bowel obstruction (SBO) have been increasingly recognized as uncommon but clinically important causes of transient ECG abnormalities.

Several case reports document that gastric dilatation or SBO may produce ST-segment elevation or repolarization abnormalities, often resolving promptly after gastrointestinal decompression and occurring in the absence of myocardial injury (

1,

2,

3). Acute gastric distension has also been associated with striking J-waves or pseudoinfarction patterns, further illustrating the broad ECG spectrum of abdominal pseudo-STEMI (

4). SBO, including closed-loop configurations, has been described as a cause of transient anterior or inferior ST elevation, occasionally leading to unnecessary activation of invasive cardiac pathways (

5,

6).

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed. Classic physiological observations showed that gastric distension may displace the heart, modifying the spatial relationship between myocardial vectors and precordial leads (

7). In such cases, ST-segment elevation may reflect alterations in cardiac position rather than true ischemia.

Beyond previously published reports of pseudo-STEMI related to gastric dilatation or small bowel obstruction, the present case offers several distinctive features. First, the ST-segment elevation occurred in a patient with known ischemic heart disease and a prior inferior myocardial infarction, a context in which the threshold for activating invasive coronary pathways is understandably low. Second, the availability of detailed echocardiographic assessment, including global longitudinal strain, allowed a refined evaluation of regional function and strongly supported the absence of new ischemia. Third, the underlying cause was a surgically confirmed closed-loop SBO due to volvulus around a double adhesion band, a mechanism rarely described in association with pseudo-STEMI. Finally, the rapid and complete normalization of ST-segment elevation within minutes after nasogastric decompression provides compelling temporal evidence for a causal link between gastrointestinal distension and the transient ECG changes.

2. Case Presentation

A 68-year-old man with a history of ischemic heart disease and a previous inferior myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention and a drug-eluting stent on the right coronary artery presented to the emergency department with a two-day history of diffuse abdominal pain, progressive distension, and complete absence of bowel movements and gas. His home medications included bisoprolol 1.25 mg daily, ramipril 5 mg daily, aspirin 100 mg daily, and rosuvastatin 10 mg daily. He reported no chest pain, dyspnea, palpitations, or other cardiopulmonary symptoms.

On arrival, his vital signs were within normal limits: blood pressure 130/80 mmHg, heart rate 75 bpm, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. He was afebrile. On physical examination, the abdomen was markedly distended and tympanitic, with diffuse tenderness and markedly reduced bowel sounds, although without guarding or peritoneal signs. Cardiac and pulmonary examinations were unremarkable.

Because of his cardiac history, a 12-lead ECG was obtained upon arrival confirming the Q wave in inferior leads and unexpectedly showing ST-segment elevation in the anterolateral leads (V4–V6), fulfilling the criteria for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (

Figure 1).

In light of this discordance between a STEMI-pattern ECG and a completely silent cardiac presentation, a bedside transthoracic echocardiogram was performed promptly.

The Simpson biplane left ventricular ejection fraction was 46%, consistent with mild systolic dysfunction. The anterior wall exhibited normal thickening and contractile motion, while the inferior wall showed akinesia and fibrosis, in keeping with the patient’s known prior myocardial infarction. Importantly, no new regional wall motion abnormalities were detected.

The Global Longitudinal Strain (GLS) was mildly reduced at –13.8%, reflecting the already known impairment in regional function but showing no pattern suggestive of new ischemia (

Figure 2).

Right ventricular size and function were normal, there was no pericardial effusion, and transmitral and transaortic Doppler profiles were within physiological limits.

Combined with the absence of chest pain and normal initial high-sensitivity troponin values, these findings effectively ruled out an acute coronary event as the cause of the initial ST elevation. Laboratory tests and arterial blood gas analysis showed normal hemoglobin, electrolyte levels, and oxygenation parameters, making metabolic or respiratory disturbances unlikely contributors to the transient ECG abnormalities. Serum lactate was mildly elevated at 3.8 mmol/L. Given the atypical presentation and the absence of chest pain, Takotsubo syndrome was also considered in the initial differential diagnosis. However, transthoracic echocardiography showed no apical, mid-ventricular, or basal ballooning, and regional contractility remained unchanged compared with prior examinations.

Meanwhile, the patient continued to experience significant abdominal distension. A nasogastric tube was inserted, immediately evacuating a large quantity of bilious fluid and producing rapid upper gastrointestinal decompression with prompt symptomatic improvement. A repeat ECG performed approximately fifteen minutes after nasogastric drainage showed complete resolution of the previously elevated ST segments (

Figure 3), confirming that the ECG changes were transient and almost certainly related to abdominal distension rather than myocardial ischemia.

With the cardiac cause excluded, diagnostic attention shifted to the gastrointestinal tract. A bedside abdominal ultrasound demonstrated marked gastric distension and multiple dilated small bowel loops with reduced peristalsis and visible air–fluid levels, along with a suspected transition point (

Figure 4 A, B).

To better delineate the pathology, a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen was performed. The CT confirmed massive gastric dilatation and diffusely distended ileal loops (

Figure 5 A, B, C), with a sharply demarcated transition point and a mesenteric “whirl sign” consistent with a closed-loop obstruction due to volvulus. There was no pneumatosis, portal venous gas, free air, or other radiologic markers of irreversible bowel ischemia.

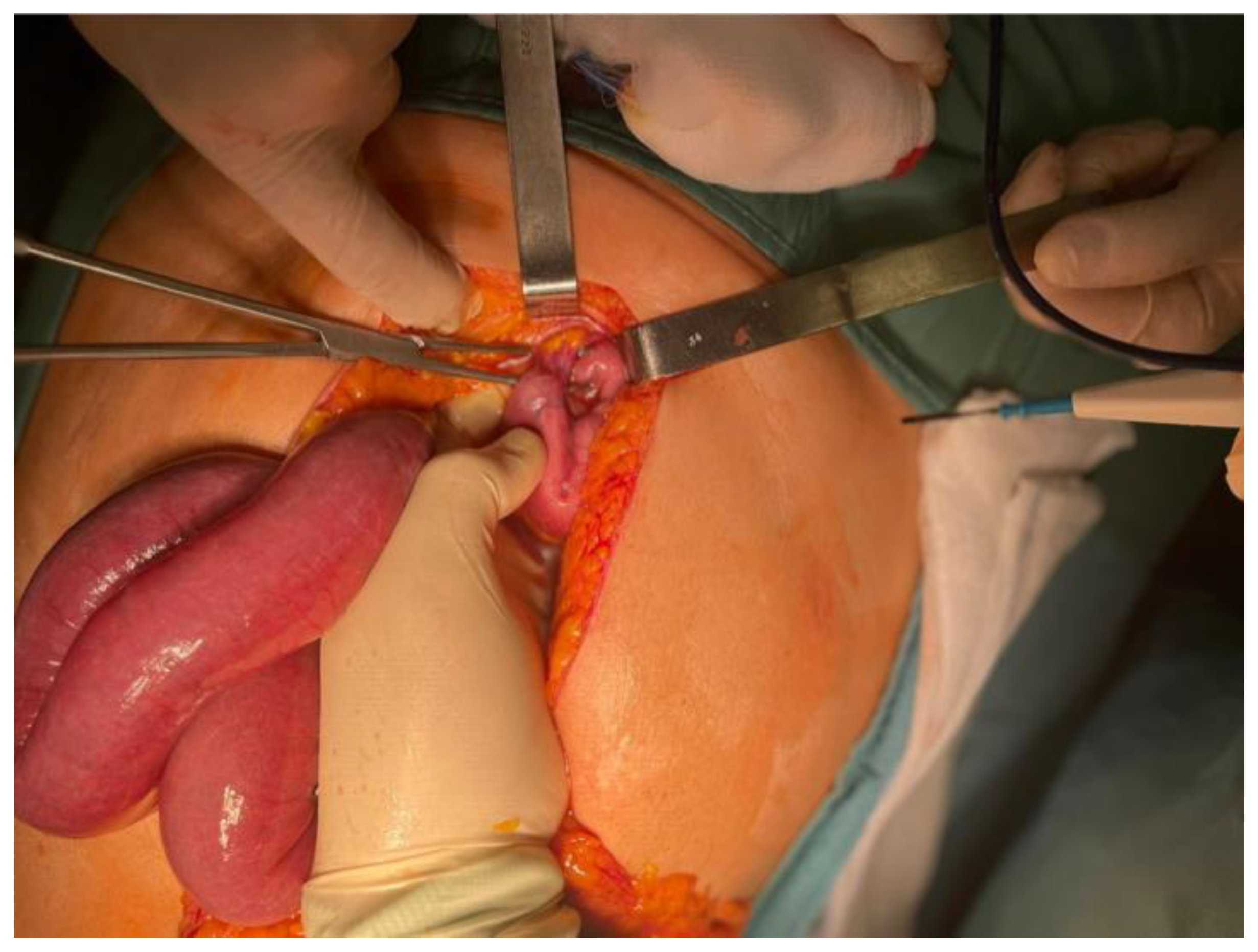

Given the imaging findings and the risk of strangulation, the patient was taken urgently to the operating room for exploratory laparotomy. Through a supra- and infraumbilical incision, the surgical team identified a segment of small bowel that had volvulated around a double fibrous adhesion band, resulting in venous congestion of the entrapped loops (

Figure 6). The adhesions were carefully lysed, the volvulus was reduced, and the congested bowel was wrapped in warm saline-soaked gauze for fifteen minutes. During this time, the loop progressively regained normal color, peristaltic activity, and mesenteric pulsatility, confirming its full viability and eliminating the need for resection. A small segment of friable omentum was excised, a 24 French pelvic drain was placed, meticulous hemostasis was secured, and the abdominal wall was closed in layers.

The patient recovered steadily, with prompt resolution of abdominal distension and progressive return of bowel function. No further ECG abnormalities were observed during hospitalization. He was discharged home in good clinical condition on postoperative day four.

3. Discussion

This case illustrates a diagnostically challenging presentation of abdominal pseudo-STEMI, an entity in which gastrointestinal pathology produces transient ECG abnormalities mimicking acute coronary occlusion. Similar cases have been reported in the literature, where ST-segment elevation normalized rapidly after decompression of severe gastric or intestinal distension, and cardiac biomarkers remained negative (

8,

9). These observations reinforce the concept that not all ST-elevation patterns represent myocardial infarction and that extracardiac causes must be considered in atypical scenarios.

Several pathophysiological mechanisms may explain this phenomenon. First, mechanical displacement of the heart due to diaphragmatic elevation from massive gastric or intestinal distension may alter the electrical axis and precordial lead orientation, generating apparent ST elevation without true ischemia. Computational modeling studies support this mechanism, demonstrating that relatively small changes in cardiac position can significantly modify surface ECG morphology (

10). Second, autonomic reflexes activated by visceral distension may transiently influence coronary vasomotor tone or repolarization currents, leading to pseudo-ischemic ECG changes despite normal myocardial perfusion (

11). Third, severe abdominal distension may increase intra-abdominal pressure, impairing venous return and altering ventricular loading conditions in ways that resemble ischemic physiology (

12).

Although mechanical bowel obstruction can represent an unusual physical trigger for Takotsubo syndrome (

13), in this patient the diagnosis was rapidly ruled out thanks to a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiographic assessment, which showed no ballooning patterns and no new regional wall motion abnormalities.

The present case aligns with reports of SBO-induced ECG abnormalities in which ST elevation involved anterior, lateral, or inferior leads, emphasizing that pseudo-STEMI is not regionally specific and may mimic various occlusion patterns (

14). Importantly, distinguishing pseudo-STEMI from true ischemia requires immediate echocardiography: the absence of new regional wall motion abnormalities in our patient effectively excluded transmural infarction and prevented unnecessary coronary angiography. Compared with previously reported cases of gastrointestinal pseudo-STEMI, this patient illustrates several clinically relevant nuances. Cases of SBO mimicking STEMI have generally involved patients without a prior history of myocardial infarction, in whom the pre-test probability of acute coronary occlusion was lower. In our patient, the coexistence of prior inferior infarction with chronic wall motion abnormalities significantly increased the likelihood of misinterpreting the new ST-segment elevation as a recurrent coronary event. Moreover, detailed echocardiographic analysis with global longitudinal strain is seldom reported in similar cases and provided an additional, sensitive tool to exclude new regional dysfunction.

The surgically documented closed-loop obstruction caused by volvulus around a double adhesion band further adds to the spectrum of mechanical etiologies of abdominal pseudo-STEMI. Taken together, these elements underscore the importance of integrating advanced cardiac imaging and definitive surgical findings when interpreting atypical ST-segment elevation patterns in patients with known ischemic heart disease.

From a surgical perspective, closed-loop SBO is a time-sensitive emergency. CT findings such as a transition point or mesenteric swirl pattern help identify volvulus early, preventing progression to bowel ischemia (

15). In our patient, prompt recognition and adhesiolysis allowed full bowel recovery without resection.

Overall, this case underscores the importance of integrating cardiac and abdominal evaluation in patients presenting with ST elevation and gastrointestinal symptoms. Awareness of abdominal pseudo-STEMI can prevent unnecessary activation of interventional pathways while ensuring timely management of life-threatening abdominal emergencies.

4. Conclusion

This case demonstrates how severe abdominal distension secondary to mechanical small bowel obstruction can generate transient ST-segment elevation closely mimicking acute myocardial infarction. The immediate resolution of ECG abnormalities after nasogastric decompression, together with the absence of biomarker elevation and unchanged regional wall motion on echocardiography, allowed clinicians to confidently exclude acute coronary occlusion. Recognizing these pseudo-ischemic patterns is essential to avoid unnecessary and potentially harmful cardiac interventions. At the same time, timely abdominal evaluation is critical, as closed-loop obstruction represents a surgical emergency with a risk of rapid progression to bowel ischemia. Integrated interpretation of ECG findings, hemodynamic data, and abdominal imaging remains pivotal for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management in similar presentations.

Author Contributions

Fu.C. conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. Fu.C, A.I., A.S. and Fl.C. collected and interpreted clinical data. F.F. and A.D.M. performed surgical intervention and contributed to manuscript revision. All authors approved the final version.

Funding

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013. According to the guideline of the Ethics Committee of “Antonio Cardarelli” Hospital, publication of single case reports is exempt from formal ethics approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the patient. The patient also provided specific written consent for the publication of anonymized clinical images and intraoperative photographs.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Anesthesiology team at “Antonio Cardarelli” Hospital for their collaboration in patient management.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

ECG

STEMI

SBO

CT

GLS |

Electrocardiogram

ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Small Bowel Obstruction

Computed Tomography

Global Longitudinal Strain |

References

- Herath HM, Thushara Matthias A, Keragala BS, Udeshika WA, Kulatunga A. Gastric dilatation and intestinal obstruction mimicking acute coronary syndrome with dynamic electrocardiographic changes. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016 Nov 29;16(1):245. PMID: 27899069; PMCID: PMC5129209. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Basrawala H, Patel S, Girn H, Eyvazian V, Wang L, Ostrzega E. Gastrointestinal Distention Masquerading as ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JACC Case Rep. 2020 Apr 15;2(4):604-610. PMID: 34317304; PMCID: PMC8298783. [CrossRef]

- Hibbs J, Orlandi Q, Olivari MT, Dickey W, Sharkey SW. Giant J Waves and ST-Segment Elevation Associated With Acute Gastric Distension. Circulation. 2016 Mar 15;133(11):1132-4. PMID: 26976919. [CrossRef]

- Patel K, Chang NL, Shulik O, DePasquale J, Shamoon F. Small Bowel Obstruction Mimicking Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:739147. Epub 2015 Mar 8. PMID: 25838963; PMCID: PMC4370232. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay A, Chauhan S, Jangda U, Bodar V, Al-Chalabi A. Reversible Inferolateral ST-Segment Elevation Associated with Small Bowel Obstruction. Case Rep Med. 2017;2017:5982910. Epub 2017 Mar 30. PMID: 28465689; PMCID: PMC5390630. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin NK, Ives CW, Morgan WS, Bowman MH, Chatterjee A. Small Bowel Obstruction Mimicking Acute Inferior ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am J Med. 2021 May;134(5):599-602. Epub 2020 Dec 13. PMID: 33316250. [CrossRef]

- Duke M. Positional effects of gastric distention upon the mean electrical axis of the QRS complex of the electrocardiogram. Vasc Dis. 1965 Jul;2(4):161-7. PMID: 5827357.

- Pollack ML. ECG manifestations of selected extracardiac diseases. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006 Feb;24(1):133-43, vii. PMID: 16308116. [CrossRef]

- Frais MA, Rodgers K. Dramatic electrocardiographic T-wave changes associated with gastric dilatation. Chest. 1990 Aug;98(2):489-90. PMID: 2376185. [CrossRef]

- Swenson DJ, Geneser SE, Stinstra JG, Kirby RM, MacLeod RS. Cardiac position sensitivity study in the electrocardiographic forward problem using stochastic collocation and boundary element methods. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011 Dec;39(12):2900-10. Epub 2011 Sep 10. PMID: 21909818; PMCID: PMC3362042. [CrossRef]

- Malbrain ML, De Waele JJ, De Keulenaer BL. What every ICU clinician needs to know about the cardiovascular effects caused by abdominal hypertension. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2015;47(4):388-99. Epub 2015 May 14. PMID: 25973663. [CrossRef]

- Roggo A, Ottinger LW. Acute small bowel volvulus in adults. A sporadic form of strangulating intestinal obstruction. Ann Surg. 1992 Aug;216(2):135-41. PMID: 1503517; PMCID: PMC1242584. [CrossRef]

- Cacciapuoti F, Capone V, Crispo S, Gottilla R, La Rocca F, Esposito M, Mauro C. Beyond the Broken Heart: Unusual Triggers of Stress Cardiomyopathy – A Narrative Review. Heart and Mind 9(3):p 215-223, May–Jun 2025. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Chhabra L, Killeen R, Brady WJ. Small bowel obstruction causing dynamic ECG changes mimicking acute coronary syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(9):1705.e1–1705.e4.

- Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Smullen TL, Platt JF. Closed-loop small-bowel obstruction: diagnostic patterns by multidetector computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007 Sep-Oct;31(5):697-701. PMID: 17895779. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).