Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

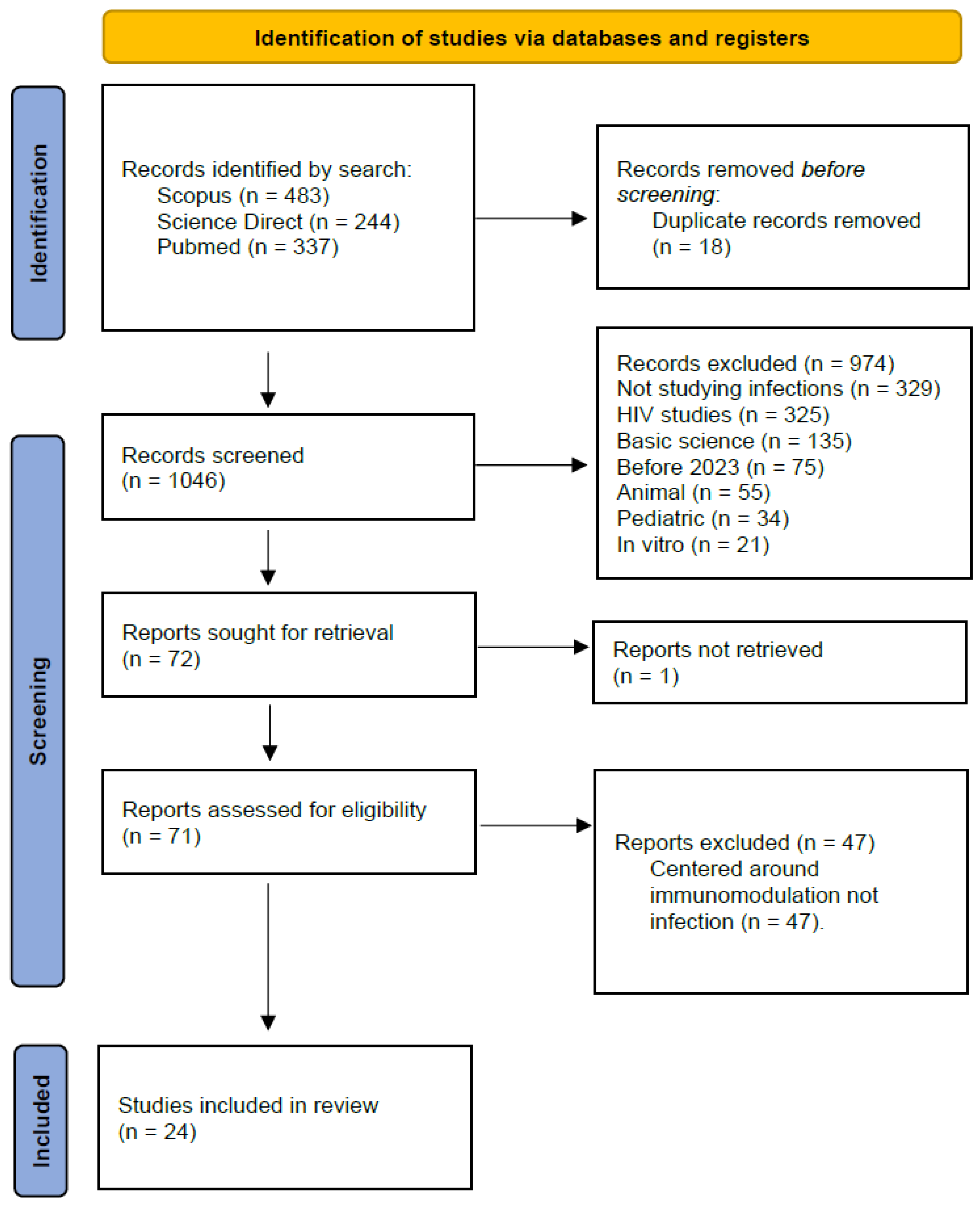

Background: Immunomodulatory therapies, including biologics, JAK inhibitors, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and bispecific antibodies (BsAbs), have reshaped the treatment of autoimmune diseases and malignancies. They alter host defenses, but the current landscape of associated infectious risk is not fully defined. Objective: I conducted a scoping review of recent literature to characterize infectious complications associated with modern immunomodulatory drugs, summarize current pathogen patterns, and highlight recommendations for prevention and early recognition in clinical practice. Methods: Following PRISMA-ScR guidelines, I systematically searched Scopus, Science Direct, and PubMed for studies published since 2023. Inclusion criteria focused on adult human subjects, exposure to immunomodulatory therapy, and reported infectious outcomes. After screening 1,046 unique records, 24 studies were included in the final review. Findings: High-dose glucocorticoids remain a primary driver of serious infections across autoimmune diseases. Newer agents present mechanism-specific risk profiles. JAK inhibitors are associated with herpes zoster, while TNF-α inhibitors are linked to opportunistic bacterial infections and reactivation of granulomatous infections. B-cell depletion with rituximab correlates with hypogammaglobulinemia and its associated infections, whereas belimumab may offer a lower infection risk in non-renal SLE. In oncology, bispecific antibodies have a high incidence of severe infections, driven by neutropenia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Immune checkpoint inhibitors were associated with a 26.9% serious infection rate, with complications difficult to distinguish from immune-related adverse events. Conclusion: The infectious risk associated with modern immunomodulators is not one profile, but a spectrum of specific vulnerabilities. This review shows the urgent need for individualized risk stratification, targeted prophylaxis (e.g., for Pneumocystis or zoster), and pre-therapy screening to balance therapeutic efficacy with patient safety.

Keywords:

Introduction:

Methods:

Results:

Findings:

Discussion:

Limitations:

Conclusion

References

- Immunomodulators. Cancer Research Institute. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.cancerresearch.org/immunotherapy-by-treatment-types/immunomodulators.

- Dropulic LK, Lederman HM. Overview of Infections in the Immunocompromised Host. Microbiology Spectrum. 2016;4(4):10.1128/microbiolspec.dmih2-0026-2016. [CrossRef]

- Sharma Y, Arora M, Bala K. The potential of immunomodulators in shaping the future of healthcare. Discov Med. 2024;1(1):37. [CrossRef]

- PRISMA statement. PRISMA statement. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.prisma-statement.org.

- Rayyan: AI-Powered Systematic Review Management Platform. Accessed November 10, 2025. https://www.rayyan.ai/.

- Bril V, Gilhus NE. Aging and infectious diseases in myasthenia gravis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2025;468:123314. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Y, CostéDoat-Chalumeau N. Serious infections in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: how can we prevent them? The Lancet Rheumatology. 2023;5(5):e245-e246. [CrossRef]

- Mena-Vázquez N, Redondo-Rodriguez R, Rojas-Giménez M, et al. Rate of severe and fatal infections in a cohort of patients with interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter prospective study. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Ko T, Koelmeyer R, Li N, et al. Predictors of infection requiring hospitalization in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a time-to-event analysis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2022;57. [CrossRef]

- Huang WN, Chuo CY, Lin CH, et al. Serious Infection Rates Among Patients with Select Autoimmune Conditions: A Claims-Based Retrospective Cohort Study from Taiwan and the USA. Rheumatology and Therapy. 2023;10(2):387-404. [CrossRef]

- Choi SR, Ha YJ, Park JK, et al. POS0912 A NOVEL SCORING SYSTEM TO PREDICT SERIOUS INFECTIONS IN PATIENTS WITH RHEUMATIC DISEASES RECEIVING PROLONGED, HIGH-DOSE GLUCOCORTICOID TREATMENT. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2024;83:1151. [CrossRef]

- Liberatore J, Nguyen Y, Hadjadj J, et al. Risk factors for hypogammaglobulinemia and association with relapse and severe infections in ANCA-associated vasculitis: A cohort study. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2024;142:103130. [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulos A, Vassilopoulos S, Kalligeros M, Shehadeh F, Mylonakis E. Incidence of serious infections in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis receiving immunosuppressive therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Medicine. 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Smith RM, Jones RB, Specks U, et al. Rituximab versus azathioprine for maintenance of remission for patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis and relapsing disease: an international randomised controlled trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2023;82(7):937-944. [CrossRef]

- Rodziewicz M, Dyball S, Lunt M, et al. Early infection risk in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus treated with rituximab or belimumab from the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Biologics Register (BILAG-BR): a prospective longitudinal study. The Lancet Rheumatology. 2023;5(5):e284-e292. [CrossRef]

- Materne E, Choi H, Zhou B, Costenbader KH, Zhang Y, Jorge A. Comparative Risks of Infection With Belimumab Versus Oral Immunosuppressants in Patients With Nonrenal Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatology. 2023;75(11):1994-2002. [CrossRef]

- Lee YT, Chen CC, Chen SC. Risk of serious infection between belimumab and oral immunosuppressants for non-renal systemic lupus erythematosus: comment on the article by Materne et al. Arthritis and Rheumatology. 2023;75(12):2266-2267. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Chi G, Xia S, et al. Infectious complications of Belimumab with standard care in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2025;73. [CrossRef]

- Lakhmiri R, Cherrah Y, Serragui S. Tumor Necrosis Alpha (TNF-α) Antagonists Used in Chronic Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases: Risks and their Minimization Measures. Current Drug Safety. 2024;19(4):431-443. [CrossRef]

- Altuwaijri M, Alkhraiji N, Almasry M, Alkhowaiter S, Al Amaar N, Alotaibi A. Brucellosis in a patient with Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab: A case report. Arab Journal of Gastroenterology. 2025;26(1):38-40. [CrossRef]

- McInnes IB, Kato K, Magrey M, et al. POS0835 LONG-TERM SAFETY AND EFFICACY OF UPADACITINIB IN PATIENTS WITH PSORIATIC ARTHRITIS: 5-YEAR RESULTS FROM THE PHASE 3 SELECT-PsA 1 STUDY. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2025;84:980-981. [CrossRef]

- Petri M, Bruce IN, Dörner T, et al. Baricitinib for systemic lupus erythematosus: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial (SLE-BRAVE-II). The Lancet. 2023;401(10381):1011-1019. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Wu YX, Hu WP, Zhang J. Incidence and risk factors of serious infections occurred in patients with lung cancer following immune checkpoint blockade therapy. BMC Cancer. 2025;25(1).

- Miyamoto M, Tamagawa S, Kono M, et al. A rare case of Pseudomonas aeruginosa enteritis induced by pembrolizumab. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2023;50(5):836-840. [CrossRef]

- Mazahreh F, Mazahreh L, Schinke C, et al. Risk of infections associated with the use of bispecific antibodies in multiple myeloma: a pooled analysis. Blood Advances. 2023;7(13):3069-3074. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Hutton GJ, Varisco TJ, Lin Y, Essien EJ, Aparasu RR. Infection Risk Associated with High-Efficacy Disease-Modifying Agents in Multiple Sclerosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2025;117(2):561-569. [CrossRef]

- Langer-Gould AM, Smith JB, Gonzales EG, Piehl F, Li BH. Multiple Sclerosis, Disease-Modifying Therapies, and Infections. Neurology: Neuroimmunology and NeuroInflammation. 2023;10(6). [CrossRef]

- Takahashi J, Okamoto T, Lin Y, et al. Ratio of lymphocyte to monocyte area under the curve as a novel predictive factor for severe infection in multiple sclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Fenne IJ, Askildsen Oftebro G, Vestergaard C, Frølunde AS, Bech R. Effect of early initiation of steroid-sparing drugs in patients with bullous pemphigoid. Front Immunol. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Caplan AS, Mecoli CA, Micheletti RG. Prophylaxis Against Pneumocystis Pneumonia. JAMA. 2023;330(19):1908-1909. [CrossRef]

- Malpica L, Moll S. Practical approach to monitoring and prevention of infectious complications associated with systemic corticosteroids, antimetabolites, cyclosporine, and cyclophosphamide in nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2020;2020(1):319-327. [CrossRef]

- Varley CD, Winthrop KL. Long-Term Safety of Rituximab (Risks of Viral and Opportunistic Infections). Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2021;23(9):74. [CrossRef]

- Engel ER, Walter JE. Rituximab and eculizumab when treating nonmalignant hematologic disorders: infection risk, immunization recommendations, and antimicrobial prophylaxis needs. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2020;2020(1):312-318. [CrossRef]

- Ginzler EM, Wallace DJ, Merrill JT, et al. Disease Control and Safety of Belimumab Plus Standard Therapy Over 7 Years in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2014;41(2):300-309. [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer L, Miko BA, Pereira MR. Infectious Disease Prophylaxis During and After Immunosuppressive Therapy. Kidney International Reports. 2024;9(8):2337-2352. [CrossRef]

- Gerriets V, Goyal A, Khaddour K. Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed November 10, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482425/.

- Robert M, Miossec P. Reactivation of latent tuberculosis with TNF inhibitors: critical role of the beta 2 chain of the IL-12 receptor. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(7):1644-1651. [CrossRef]

- Ali T, Kaitha S, Mahmood S, Ftesi A, Stone J, Bronze MS. Clinical use of anti-TNF therapy and increased risk of infections. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2013;5:79-99. [CrossRef]

- McInnes IB, Kato K, Magrey M, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Upadacitinib in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis: 2-Year Results from the Phase 3 SELECT-PsA 1 Study. Rheumatol Ther. 2023;10(1):275-292. [CrossRef]

- Narbutt J, Żuber Z, Lesiak A, Bień N, Szepietowski JC. Vaccinations in Selected Immune-Related Diseases Treated with Biological Drugs and JAK Inhibitors—Literature Review and Statement of Experts from Polish Dermatological Society. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12(1):82. [CrossRef]

- PAPADAKIS M, KARNIADAKIS I, MAZONAKIS N, AKINOSOGLOU K, TSIOUTIS C, SPERNOVASILIS N. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Infection: What Is the Interplay? In Vivo. 2023;37(6):2409-2420. [CrossRef]

- Raje N, Anderson K, Einsele H, et al. Monitoring, prophylaxis, and treatment of infections in patients with MM receiving bispecific antibody therapy: consensus recommendations from an expert panel. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13(1):116. [CrossRef]

- Stoll S, Costello K, Newsome SD, Schmidt H, Sullivan AB, Hendin B. Insights for Healthcare Providers on Shared Decision-Making in Multiple Sclerosis: A Narrative Review. Neurol Ther. 2024;13(1):21-37. [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer F, Laurent S, Fink GR, Barnett MH, Hartung HP, Warnke C. Effects of disease-modifying therapy on peripheral leukocytes in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2021;268(7):2379-2389. [CrossRef]

- Uslu EU, Sezer S, Torğutalp M, et al. The factors predicting development of serious infections in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Sarcoidosis Vasculitis and Diffuse Lung Diseases. 2023;40(2). [CrossRef]

| Source of Evidence (Citation) | Characteristics of Evidence | Relevant Charted Data (Relating to Review Questions & Objectives) |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Necrosis Alpha (TNF-α) Antagonists Used in Chronic Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases: Risks and their Minimization Measures, 2024 | Comprehensive Review | Risk Factors: Use of TNF-α inhibitors. Pathogen Patterns: Serious infections (general), Tuberculosis (TB), malignancy, heart failure. Prevention/Management: Highlights the critical need for Risk Management Plans (RMPs), including routine measures (labeling, package leaflets) and additional measures (educational programs for providers and patients) to minimize known risks. |

| Brucellosis in a patient with Crohn's disease treated with infliximab: A case report, 2025 | Case Report | Risk Factors: Treatment with infliximab (a TNF-α antagonist) and azathioprine for Crohn's disease. Pathogen Patterns: Brucellosis (Brucella species), an opportunistic infection, contracted from raw milk. Prevention/Management: Infliximab and azathioprine were held; patient was treated with antibiotics (rifampin, doxycycline, streptomycin) and biologics were resumed after 4 weeks. Highlights the need for multidisciplinary (Gastroenterology, Infectious Disease) management. |

| A rare case of Pseudomonas aeruginosa enteritis induced by pembrolizumab, 2023 | Case Report | Risk Factors: Treatment with pembrolizumab (an immune checkpoint inhibitor, ICI). Pathogen Patterns: Pseudomonal enteritis (P. aeruginosa), leading to septic shock. Prevention/Management: Recommends a high level of alertness for infectious complications with biologic-targeted drugs. Patient was successfully treated with corticosteroids and antibiotics. |

| Pos0912 A Novel Scoring System to Predict Serious Infections In Patients With Rheumatic Diseases Receiving Prolonged, High-Dose Glucocorticoid Treatment, 2024 | Cohort Study (Development & Validation) | Risk Factors: Prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids (GCs). Developed a scoring system identifying 7 key predictors for serious infection: age ≥65, interstitial lung disease (ILD), lymphopenia, decreased renal function, low serum albumin, concomitant cyclophosphamide use, and concomitant rituximab use. Pathogen Patterns: Serious infections (general). Incidence rate was 10.5 per 100 person-years in the derivation cohort. High-risk group (score ≥4) had an IR of 40.1 per 100 person-years. |

| Pos0835 Long-Term Safety And Efficacy Of Upadacitinib In Patients With Psoriatic Arthritis: 5-Year Results From the Phase 3 Select-PSA 1 Study, 2025 | Phase 3 Clinical Trial (Long-term Extension) | Risk Factors: Long-term (5-year) treatment with upadacitinib (a JAK inhibitor) vs. adalimumab (a TNF-α inhibitor). Pathogen Patterns: Rates of serious infection were low and similar between groups. Rates of herpes zoster were higher with upadacitinib compared to adalimumab. |

| Risk factors for hypogammaglobulinemia and association with relapse and severe infections in ANCA-associated vasculitis: A cohort study, 2024 | Cohort Study | Risk Factors: Rituximab treatment. Hypogammaglobulinemia (gammaglobulin <6 g/L and >25% decline) was a key biomarker, associated with a 2.3-fold increased risk (aHR 2.3) of severe infection. Methylprednisolone pulses at induction also independently increased infection risk (HR 5.6). Prevention/Management: Gammaglobulin decline was not associated with a lower risk of vasculitis relapse, suggesting infection risk can be managed separately from disease control. |

| Rituximab versus azathioprine for maintenance of remission for patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis and relapsing disease: an international randomised controlled trial, 2023 | Randomized Controlled Trial (RITAZAREM) | Risk Factors: Rituximab vs. azathioprine for AAV maintenance. Pathogen Patterns: Rituximab was superior for preventing relapse. Critically, the rituximab group experienced fewer serious adverse events (22%) compared to the azathioprine group (36%). No difference in rates of hypogammaglobulinemia or general infection was reported between groups. |

| Risk of infections associated with the use of bispecific antibodies in multiple myeloma: a pooled analysis, 2023 | Pooled Analysis / Meta-Analysis | Risk Factors: Treatment with bispecific antibodies (BsAbs). BCMA-targeting BsAbs (30% Grade III/IV infection) carried a higher risk than non-BCMA-targeting BsAbs (11.9%). Pathogen Patterns: High infection rates: 50% of patients developed an infection (24.5% Grade III/IV). Specific pathogens included Grade III/IV pneumonia (10%) and Grade III/IV COVID-19 (11.4%). Infections caused 25.5% of all deaths. Prevention/Management: Highlights need for precautions (e.g., IVIG use) to mitigate risk. |

| Baricitinib for systemic lupus erythematosus: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial (SLE-BRAVE-II), 2023 | Phase 3 Clinical Trial | Risk Factors: Treatment with baricitinib (a JAK inhibitor). Pathogen Patterns: The trial failed to meet its primary efficacy endpoint. Serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred in 11-13% of patients (vs. 9% placebo). No new safety signals were identified. |

| Incidence and risk factors of serious infections occurred in patients with lung cancer following immune checkpoint blockade therapy, 2025 | Retrospective Analysis | Risk Factors: Treatment with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs). Key risk factors were patient comorbidities: COPD, asthma, and low lymphocyte count. Pathogen Patterns: High serious infection rate of 26.90%. Pathogens were predominantly bacterial (85.07%), but also included Mycobacterium tuberculosis (6.47%), viral (4.98%), and fungal (3.48%). The lung was the main site. |

| Infectious complications of Belimumab with standard care in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2025 | Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis | Risk Factors: Belimumab + standard care. Pathogen Patterns: Belimumab was found to not significantly increase the risk of infections or serious infections compared to standard care alone. The overall incidence of serious infections was low. |

| Infection Risk Associated with High-Efficacy Disease-Modifying Agents in Multiple Sclerosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study, 2025 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Risk Factors: High-Efficacy Disease-Modifying Agents (heDMAs) vs. moderate-efficacy (meDMAs). Pathogen Patterns: heDMAs were associated with a 1.24-fold higher risk (aHR 1.24) of serious infection and a 1.21-fold higher risk (aHR 1.21) of urinary tract infections (UTIs). Prevention/Management: Highlights the need for careful monitoring and management of infection risk in this group. |

| Rate of severe and fatal infections in a cohort of patients with interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter prospective study, 2024 | Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study | Risk Factors: Disease state of Rheumatoid Arthritis-associated Interstitial Lung Disease (RA-ILD). Pathogen Patterns: Extremely high incidence rate of serious infection: 52.6 per 100 person-years. 65% of all deaths in the cohort were directly related to infection. Common sites: respiratory tract, urinary tract, skin/soft tissue. |

| Risk of serious infection between belimumab and oral immunosuppressants for non-renal systemic lupus erythematosus: comment on the article by Materne et al, 2023 | Letter/Commentary | Risk Factors: Belimumab vs. oral immunosuppressants. Prevention/Management: Supports the findings of the main paper, reinforcing the observation that belimumab may have a favorable safety profile regarding infection risk. |

| Comparative Risks of Infection With Belimumab Versus Oral Immunosuppressants in Patients With Nonrenal Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, 2023 | Observational Cohort Study | Risk Factors: Belimumab vs. Azathioprine (AZA) vs. Mycophenolate (MMF). Pathogen Patterns: Belimumab was associated with a lower risk of serious infection compared to AZA (aHR 0.82) and MMF (aHR 0.69). Prevention/Management: Suggests belimumab may be a safer treatment option regarding infection risk for SLE patients without lupus nephritis. |

| Multiple Sclerosis, Disease-Modifying Therapies, and Infections, 2023 | Review / Registry Data Analysis | Risk Factors: Specific MS therapies. Pathogen Patterns: Fingolimod and Rituximab were associated with a higher risk of serious infection (especially pneumonia) compared to injectable therapies. Natalizumab was associated with a lower risk. |

| The factors predicting development of serious infections in ANCA-associated vasculitis, 2023 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Risk Factors: Disease-specific factors in AAV. Identified independent predictors: renopulmonary involvement, age over 65, and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Pathogen Patterns: Serious infections occurred in 50% of the 84 AAV patients. |

| Serious infections in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: how can we prevent them?, 2023 | Editorial / Commentary | Risk Factors: SLE disease state, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants. Prevention/Management: Calls for better risk stratification to identify high-risk patients, use of steroid-sparing agents (like belimumab), and implementation of preventive measures (e.g., vaccinations, Pneumocystis prophylaxis). |

| Early infection risk in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus treated with rituximab or belimumab from the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group Biologics Register (BILAG-BR): a prospective longitudinal study, 2023 | Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Study | Risk Factors: Rituximab vs. Belimumab in SLE. Pathogen Patterns: Incidence of serious infection in the first 12 months was 13.9% for rituximab and 12.5% for belimumab. The risk was not significantly different between the two drugs. Risk Factors: Baseline hypogammaglobulinemia and higher glucocorticoid dose were predictors of serious infection. |

| Serious Infection Rates Among Patients with Select Autoimmune Conditions: A Claims-Based Retrospective Cohort Study from Taiwan and the USA, 2023 | Retrospective Cohort Study | Risk Factors: Disease states of SLE, Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), and primary membranous nephropathy. Pathogen Patterns: Rates of serious infection were significantly higher in all autoimmune cohorts compared to the general population. Patients with lupus nephritis had the highest burden (7- to 25-fold higher risk). Infections were driven by bacterial, respiratory, urinary tract, and opportunistic infections. |

| Incidence of serious infections in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis receiving immunosuppressive therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis, 2023 | Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis | Risk Factors: Different immunosuppressants for AAV maintenance. Pathogen Patterns: Overall cumulative incidence of SI was 15.99%. Incidence for rituximab was 14.61%; for azathioprine, 5.93%; for CYC+AZA, 20.81%. Most fatal SIs were pneumonia and sepsis. |

| Ratio of lymphocyte to monocyte area under the curve as a novel predictive factor for severe infection in multiple sclerosis, 2023 | Retrospective Review | Risk Factors: Disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) in MS. Prevention/Management: Identified a novel biomarker: a lower ratio of lymphocyte AUC to monocyte AUC (L_AUC/t to M_AUC/t) was associated with decreased risk of serious infection. Suggests monitoring these cell count ratios may be more important than the specific drug used. |

| Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Infection: What Is the Interplay?, 2023 | Narrative Review | Risk Factors: Treatment with ICIs. Pathogen Patterns: ICIs per se do not seem to generally increase infection risk. However, infectious complications are often related to the immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., corticosteroids) used to manage the immune-related adverse events (irAEs) caused by the ICIs. |

| Aging and infectious diseases in myasthenia gravis, 2025 | Review | Risk Factors: Myasthenia Gravis (MG) disease state, aging, and immunosenescence. Pathogen Patterns: Increased susceptibility to infection; respiratory tract disease is a frequent precipitating factor for myasthenic crisis and a major contributor to mortality. |

| Drug Class | Specific Drug(s) | Associated Disease(s) | Infectious Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids (GCs) | Prednisone Prednisolone Methylprednisolone Dexamethasone |

Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases (AIRDs) | Serious Infections (general); Incidence Rate 10.5 per 100 person-years. Risk factors: age ≥65, ILD, lymphopenia, low albumin, low eGFR. |

| ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (AAV) | Severe Infections (general); associated with GC-induced hypogammaglobulinemia (aHR 2.3 for infection if low). | ||

| TNF-α Antagonists | Infliximab, Adalimumab, others | Chronic Inflammatory Rheumatism | Serious infections (general), Tuberculosis (TB) reactivation, malignancy, heart failure. Requires Risk Management Plans (RMPs). |

| Infliximab (with Azathioprine) | Crohn's Disease | Brucellosis (opportunistic infection). | |

| B-Cell Modulators | Rituximab |

ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (AAV) | Fewer serious adverse events (22%) than azathioprine (36%). No difference in general infection rates. Cumulative incidence of serious infections: 14.61% (vs 5.93% for azathioprine). Fatal SIs: Pneumonia, Sepsis. Severe Infections (general); strongly associated with hypogammaglobulinemia (aHR 2.3 for infection if low). |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | Serious infection incidence: 13.9% in the first 12 months. | ||

| Belimumab |

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | No significant increase in infection risk compared to standard care. | |

| Non-renal SLE | Lower risk of serious infection compared to Azathioprine (aHR 0.82) and Mycophenolate (aHR 0.69). | ||

| JAK Inhibitors | Upadacitinib | Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA) | Herpes zoster (higher rate than adalimumab). Rates of serious infection, malignancy, MACE, and VTE were low. |

| Baricitinib | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | Serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred in 11-13% of patients (vs. 9% placebo). No new safety signals. | |

| Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs) | Pembrolizumab | Hypopharyngeal Carcinoma | Pseudomonal enteritis (P. aeruginosa), septic shock. |

| ICIs (general) | Lung Cancer | Serious infection rate: 26.90%. Pathogens: Bacterial (85.07%), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (6.47%), Viral (4.98%), Fungal (3.48%). Risk factors: COPD, asthma. | |

| Cancer (general) | Infectious complications are often related to the immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., corticosteroids) used to treat irAEs, not the ICI itself. | ||

| Bispecific Antibodies (BsAbs) | BCMA-targeting & non-BCMA-targeting | Multiple Myeloma | All-grade infections: 50%. Grade III/IV infections: 24.5%. Grade III/IV Pneumonia: 10%. Grade III/IV COVID-19: 11.4%. Infections caused 25.5% of deaths. BCMA-targeting BsAbs had higher risk (30%) than non-BCMA (11.9%). |

| MS Therapies | High-Efficacy DMAs (heDMAs) | Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | Higher risk of serious infection (aHR 1.24) and Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) (aHR 1.21) compared to moderate-efficacy DMAs. |

| Fingolimod, Rituximab, Natalizumab | Fingolimod and Rituximab: Higher risk of serious infection (especially pneumonia). Natalizumab: Lower risk. | ||

| Other Immunosuppressants | Azathioprine | ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (AAV) | Serious adverse events (36%). Cumulative incidence of serious infection: 5.93%. |

| Mycophenolate | Non-renal SLE | Higher risk of serious infection compared to Belimumab (aHR 0.69 for Belimumab vs Mycophenolate). | |

| Disease-Specific (No Drug Specified) | N/A |

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) | Increased susceptibility to infection; respiratory tract disease is a frequent cause of death. |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis w/ ILD | Extremely high serious infection rate: 52.6 per 100 person-years. 65% of all deaths were infection-related. | ||

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) | High baseline risk, especially lupus nephritis. | ||

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | A novel biomarker (L_AUC/t to M_AUC/t ratio) was identified as a predictive factor for severe infections. |

| Drug Class | Screen Before Starting | Vaccines | Prophylaxis Needed? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids ≥20 mg/day | TB, Hep B, Strongyloides (if endemic) | Influenza & pneumococcal | Yes: TMP-SMX for PCP ≥4 weeks |

| Rituximab | IgG levels, Hep B (core Ab) | Give vaccines ≥2–4w pre-infusion | Consider PCP prophylaxis if also on steroids |

| TNF-α Inhibitors | TB (IGRA/TST), Hep B/C | Give Shingrix pre-therapy | No routine antimicrobial prophylaxis |

| JAK Inhibitors | TB, Hep B/C | Shingrix required | No routine prophylaxis unless on steroids |

| Bispecific Antibodies | CBC + IgG baseline | COVID, pneumococcal | Yes: PCP + antiviral (acyclovir) ± antifungal |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).