1. Introduction

Household financial decision-making—encompassing saving, borrowing, investing, and consumption—is a cornerstone of microeconomic well-being and a critical driver of macroeconomic resilience and capital market depth (e.g., Campbell, 2006; Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014; Agarwal et al., 2020). Within this framework, financial literacy has emerged as a pivotal determinant, with a robust body of literature affirming its positive association with prudent financial management, wealth accumulation, and the ability to withstand economic shocks (e.g., Klapper et al., 2015; Klapper & Lusardi, 2020; Erdem & Rojahn, 2022).

Yet, a persistent empirical puzzle endures, particularly in many European economies: despite documented improvements in financial knowledge, participation rates in securities markets often remain subdued (e.g., Kaustia et al., 2023; Oehler & Horn, 2023). This suggests that the relationship between literacy and complex financial behaviors is not merely direct but is filtered through a complex web of mediating and moderating variables. The Portuguese context exemplifies this puzzle. Data from the National Council of Financial Supervisors (CNSF) reveals a concerning decline in average financial knowledge between 2015 and 2023, yet direct participation in stocks, bonds, or mutual fund markets also fell significantly. This dual decline challenges simplistic knowledge-deficit models and calls for a more nuanced framework that explains how and for whom financial literacy translates into investment behavior.

This study addresses this gap by hypothesizing and testing an integrated moderated mediation framework. Leveraging a unique, multi-wave, nationally representative dataset from Portugal, we move beyond a direct-effects model to investigate the intervening role of financial resilience and the comparative power of perceived versus objective knowledge. We posit that financial literacy must first empower households to build a buffer against shocks—enhancing their financial resilience—which in turn creates the capacity to engage in financial risk-taking (e.g., Hubar et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2025). Furthermore, we argue that this pathway is not uniform but is critically contingent upon sociodemographic characteristics, which act as key boundary conditions for converting knowledge and resilience into action.

Our empirical analysis yields several significant findings that shape this revised narrative. First, we document significant changes in average financial knowledge in Portugal between 2015 and 2023, with pronounced gaps across education, income, and gender. Second, we provide robust evidence that financial resilience acts as a partial mediator: both objective and perceived financial literacy significantly bolster a household's ability to cover expenses after an income shock, and this resilience is a strong, positive predictor of market participation. Third, and crucially, we find that the effect of objective knowledge on participation is substantially attenuated when accounting for perceived knowledge, which emerges as a more powerful direct driver of investment behavior. Finally, our results consistently demonstrate that socioeconomic status (particularly income) powerfully moderates the direct link between literacy and participation, enabling knowledgeable households to actualize their potential for market investment. These results challenge direct-effects models and suggest that policy initiatives must look beyond knowledge dissemination to also foster financial resilience, self-efficacy, and address structural inequalities.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents a comprehensive literature review and develops the conceptual framework.

Section 3 formalizes the research hypotheses.

Section 4 details the data and empirical methodology.

Section 5 reports the empirical results. Finally,

Section 6 concludes by summarizing the key insights, outlining policy implications, and suggesting avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of Household Financial Behavior

The study of household finance sits at the intersection of microeconomic theory and behavioral science. Foundational consumption theories---Keynes' absolute income hypothesis, Modigliani and Brumberg's life-cycle hypothesis, and Friedman's permanent income hypothesis---provide the bedrock for understanding intertemporal choice, suggesting that rational, forward-looking households smooth consumption over their lifetimes. In a neoclassical paradigm, households are modelled as optimizing agents who allocate resources to maximize expected utility in an environment of known risks (e.g., Gollier, 2002; Campbell, 2006).

However, empirical evidence consistently reveals systematic deviations from these idealized models. Household financial decision-making is characterized by unique frictions: exposure to non-hedgeable labour income risk, holdings of illiquid assets (such as housing), and significant constraints on borrowing (e.g., Cocco et al., 2005; Gomes et al., 2021).

Moreover, decisions are frequently made under conditions of incomplete information, limited cognitive capacity, and pervasive behavioural biases, leading to 'satisficing' outcomes rather than optimal ones (e.g., Simon, 1997; Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014; Hsu et al., 2021; Barrafrem et al., 2024). These departures from full rationality underscore the critical role of psychological factors and, centrally, financial literacy---the ability to understand and use financial concepts---in shaping real-world financial outcomes.

2.2. Financial Literacy, Resilience, and the Capacity for Risk-Taking

Financial literacy has been established as a cornerstone of sound financial decision-making. Literate individuals are better equipped to plan for retirement, accumulate wealth, and manage debt effectively (e.g., Hastings et al., 2013; Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014, 2023; Fernandes et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2022). A more recent and critical line of inquiry focuses on financial literacy's role in building financial resilience---defined as the capacity to anticipate, withstand, and recover from financial shocks (e.g., Klapper & Lusardi, 2020; Liu et al., 2025).

This role can be understood through the lens of adaptive expectations. Unlike rational expectations models that assume homogeneous information interpretation, adaptive expectations posit that households revise their beliefs through learning when prior expectations prove inaccurate (Claus & Dedewanou, 2024; Enders et al., 2022; Evans & Honkapohja, 2001). Within this framework of bounded rationality, households depend on accumulated knowledge and learning capacity to navigate complex financial environments (Sent, 2018; Simon, 1997). Financial literacy provides this very foundation for adaptive learning and informed decision-making.

The mechanism through which literacy builds resilience is twofold. Directly, knowledge of budgeting, saving, and debt management enables households to build emergency buffers (Hasler et al., 2018). Indirectly, literacy may enhance financial self-efficacy---the confidence in one's ability to manage finances---which motivates proactive resilience-building behaviours (Xiao & O'Neill, 2018). This link is not automatic; it is often moderated by socioeconomic constraints. For low-income households, even high literacy may not translate into resilience due to a lack of disposable resources, creating a "floor effect" (Bianchi, 2018).

We posit that financial resilience is not merely a desirable outcome but a critical psychological and material prerequisite for engaging in financial risk-taking (e.g., Curry, 2025; Liu et al., 2025). The Portuguese context, marked by recent economic volatility and a puzzle of stagnant market participation despite slightly improving literacy scores in 2023, provides a compelling setting to examine this. We argue that literacy must first empower households to create a financial safety net (resilience), which in turn provides the financial and psychological security necessary to allocate savings to risky assets like stocks and bonds (e.g., Changwony et al., 2021).

2.3. The Participation Puzzle: Beyond a Direct Link to Capital Markets

The positive correlation between financial literacy and stock market participation is one of the most robust findings in household finance (e.g., van Rooij et al., 2011, 2012). The conventional explanation is that literacy lowers the fixed costs of participation, both informational (understanding diversification, equity risk) and procedural (navigating brokerage platforms) (Christelis et al., 2010).

Yet, a direct-effects model is increasingly seen as insufficient. In Portugal, for instance, the recent rise in financial literacy has not yielded proportional growth in retail investment. This suggests the existence of mediating and moderating variables. Firstly, the pathway is likely mediated by psychological factors like self-efficacy (e.g., Grable et al., 2008) and, as we theorize, by the material buffer provided by financial resilience. A household may understand the benefits of equities but will refrain from investing if it lacks the capacity to absorb potential short-term losses.

Secondly, the relationship is critically moderated by structural and sociodemographic factors. High income and wealth mitigate liquidity constraints, enabling the literate to act on their knowledge (e.g., Bianchi, 2018).

Similarly, institutional access---such as availability of low-cost investment platforms---can strengthen the literacy-participation link by reducing procedural barriers (e.g., Grohmann, 2018). Factors like geographic region and town size may also proxy for access to financial infrastructure and networks, further conditioning this relationship (e.g., Ndou, 2023).

This leads us to propose an integrated moderated mediation framework. We hypothesize that financial literacy fosters market participation primarily through the mechanism of enhanced financial resilience, and that this indirect pathway is not uniform but is significantly stronger for households with higher socioeconomic status and more favourable geographic contexts.

2.4. Synthesis: Towards an Integrated Framework of Literacy, Resilience, and Socioeconomic Context

The reviewed literature sets the stage for an integrated framework that moves beyond the established direct correlation to illuminate how (through mediating mechanisms) and for whom (under which moderating conditions) financial literacy translates into capital market participation. The core proposition emerging from this review is that financial resilience serves as a critical mediating channel, the strength of which is powerfully moderated by a household's structural position.

The hypothesis that financial resilience acts as a mediator between financial literacy and market participation provides a crucial explanatory mechanism for the often-observed but imperfect direct link (van Rooij, Lusardi, & Alessie, 2011). This aligns with a growing body of research that conceptualizes financial behavior as a sequential process, empirically validating the theoretical notion that literacy must first empower households to build a buffer against shocks (Klapper & Lusardi, 2020; Hasler, Lusardi, & Oggero, 2018) before they can engage in discretionary risk-taking. This mediating pathway resonates with the findings of Tahir et al. (2021), who demonstrated that the relationship between financial literacy and financial well-being is mediated by financial capability, underscoring the importance of translating knowledge into tangible capacity. Similarly, the potential for perceived knowledge (self-efficacy) to operate as a parallel psychological pathway is consistent with social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997) and research emphasizing confidence as a key behavioral driver (Grable, Britt, & Webb, 2008).

However, a comprehensive framework must account for effect heterogeneity, a critical boundary condition often overlooked in simpler models. The literature strongly suggests a consistent and powerful moderating role for income and education. This affirms the "floor effect" hypothesized by Bianchi (2018), where structural resource constraints prevent the conversion of knowledge into resilience and subsequent investment. This is further elaborated by Byegon (2020), whose moderated mediation analysis found that the positive effects of self-control on financial inclusion were significantly stronger at higher levels of financial literacy, suggesting that socioeconomic resources and knowledge interact to enable proactive financial behaviors. The advantage of higher socioeconomic status is multifaceted: it not only facilitates the acquisition of knowledge but also provides the necessary liquidity to build emergency savings and the institutional access to engage with capital markets (Grohmann, 2018; Kaustia, Conlin, & Luotonen, 2023).

This interplay between knowledge, psychological factors, and structural enablers is captured in the broader literature on digital and financial capabilities. For instance, Kumar et al. (2023) argue that financial well-being emerges from an interplay of skills, digital financial literacy, and autonomy. Their findings reinforce the proposed moderated mediation framework by suggesting that the pathway from knowledge (literacy) to outcome (participation/well-being) is dependent on a set of enabling competencies and contexts—precisely what higher SES provides. This can create a self-reinforcing cycle where affluent, educated households are better equipped to use their knowledge to build resilience, which in turn unlocks higher-return investment opportunities, potentially exacerbating wealth inequality.

In summary, the integrated moderated mediation framework advanced in this study synthesizes insights from human capital, behavioral, and institutional theories. It posits that financial literacy fosters market participation not just directly, but primarily by building financial resilience, and that this entire process is profoundly shaped by socioeconomic context. The following section formalizes this framework into testable hypotheses.

3. Hypotheses

Guided by the theoretical framework above, this study develops and tests a set of hypotheses to dissect the channels linking financial literacy to capital market participation in Portugal.

H1: Financial literacy has a positive direct effect on household participation in capital markets.

Grounded in human capital theory (Becker, 1993), this hypothesis asserts that knowledge reduces informational asymmetries and lowers the perceived costs of engaging with complex financial instruments. Financially knowledgeable households are better equipped to assess risk-return trade-offs and are therefore more likely to participate in securities markets, consistent with prior evidence (e.g., van Rooij et al., 2011).

H2a: Financial resilience mediates (i.e., strengthens) the positive relationship between financial literacy and capital market participation.

We posit that a significant portion of the effect of knowledge on risk-taking is channeled through the building of a financial buffer. Financially literate households are more likely to accumulate liquid savings for emergencies (Klapper & Lusardi, 2020). This resilience, in turn, creates a safety net that enables them to tolerate the volatility of risky investments.

H2b: Perceived financial knowledge is a stronger direct predictor of capital market participation than objective financial knowledge.

Drawing on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997), we hypothesize that a psychological pathway operates. Confidence in one's ability to make sound financial decisions (perceived knowledge/self-efficacy) is crucial for the concrete action of market participation, particularly in the face of complexity and uncertainty, and may outweigh the effect of objective knowledge alone.

H3: Sociodemographic characteristics (income, education) moderate the strength of the direct relationship between financial literacy and participation (H1), such that the effect is stronger for households with higher socioeconomic status.

Informed by institutional theory (North, 1990), this hypothesis states that the capacity to convert knowledge into market participation is not uniform. Structural enablers and constraints critically condition this process. Higher income provides the necessary liquidity, while higher education may enhance access to financial information. Therefore, we expect the direct effect of literacy on participation to be more pronounced among affluent and highly educated households (Bianchi, 2018; Grohmann, 2018).

These hypotheses are tested using the robust, multi-wave dataset and the empirical strategy detailed in the following section.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Sources and Sample

This study employs a unique, multi-wave dataset constructed by pooling three nationally representative surveys: the Financial Literacy of the Portuguese Population surveys conducted in 2015, 2020, and 2023. These surveys were commissioned by the National Council of Financial Supervisors (CNSF)—comprising the Bank of Portugal, the Portuguese Securities Market Commission (CMVM), and the Portuguese Insurance and Pension Funds Supervisory Authority (ASF)—under the aegis of the Portuguese National Plan for Financial Education (PNFF).

The surveys targeted the resident population of Portugal aged 16 years or older, including the autonomous regions of Açores and Madeira. A stratified random sampling method was employed to ensure representativeness across key demographic dimensions, including gender, age, geographic location, employment status, and education level. The fieldwork for the 2015, 2020, and 2023 waves resulted in 1,100, 1,502, and 1,510 completed face-to-face interviews, respectively, yielding a final pooled sample of 4,112 observations.

To maintain consistency across waves, our analysis is restricted to questions and variables that are identical in all three survey editions. This approach ensures the comparability and integrity of the longitudinal dataset.

4.2. Variable Construction

4.2.1. Dependent Variables

Financial Resilience: Following Estrada-Mejia, Mejía, & Córdoba (2023), this variable is constructed from the survey question: "If you lost your main source of income, how long could you continue to cover your living expenses, without borrowing any money or moving house?" Responses are coded as an ordinal variable: 1 (less than a week), 2 (at least a week, but less than a month), 3 (at least a month, but less than 3 months), 4 (at least 3 months, but less than 6 months), and 5 (more than 6 months)..

Capital Market Participation: A binary dependent variable is created, equal to 1 if the respondent reported having investments in stocks, bonds, or mutual funds at the time of the survey, and 0 otherwise.

4.2.2. Independent and Mediating Variables

Financial Literacy (Objective): An objective financial knowledge score is computed based on nine financial literacy questions common to all three waves (see Annex 1). The score reflects the total number of correct answers per respondent. 'Refused to answer' and 'Don't know' responses are treated as incorrect. For multivariate analysis, this continuous measure is also categorized into terciles (Low, Average, High) to capture potential non-linear effects.

Financial Literacy (Perceived): Subjective financial knowledge is measured using respondents' self-assessment of their financial knowledge level. This variable is used to analyze the gap between perceived and objective knowledge and is included in some model specifications.

Financial Self-Efficacy: While the core analysis focuses on financial resilience as the primary mediator, the conceptual framework acknowledges the role of self-efficacy. Operationalization is derived from the confidence variable, calculated as the difference between perceived and objective knowledge categories (Abreu & Mendes, 2012). Respondents are classified as overconfident (positive difference), unbiased (zero difference), or underconfident (negative difference) (see Tables A3.1, A3.2, and A3.3, in Annex 3).

4.2.3. Moderating and Control Variables

A comprehensive set of control variables, derived from the survey, is included to account for potential confounding factors. These include:

Sociodemographic Characteristics: Age (and its square to capture non-linear life-cycle effects), gender (Female=1), marital status (Married=1), education level (university degree dummy: Schooling_high=1), employment status (active in the labour force dummy: Occupation_active=1), and household income level (categorized as High, Average, or Low).

Household Context: Geographic region of residence (dummies for Alentejo, Algarve, Center, Lisbon, North, with the islands of Açores and Madeira as the baseline) and town size (Big, Middle, with Small as the baseline).

Survey Wave Dummies: Dummy variables for the 2020 and 2023 survey waves, with 2015 as the reference category, to account for temporal effects and aggregate shocks.

4.3. Empirical Strategy

To test the hypotheses outlined in

Section 3, we employ a multi-stage empirical approach.

4.3.1. Preliminary and Descriptive Analysis

We begin by analyzing the distribution of correct answers to the financial literacy questions over time and across sociodemographic groups (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 and

Figure 1). The relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and the count of correct answers is formally estimated using a Negative Binomial regression model, robust to over-dispersion in count data (

Table 4).

4.3.2. Testing the Mediated Pathways (H1, H2a, H2b)

Our core analysis investigates the direct and indirect effects linking financial literacy to market participation. Given the binary nature of the participation variable and the ordinal nature of resilience, we estimate a series of regression models.

First, to examine the antecedent of the mediation pathway, we model the determinants of financial resilience using an ordered logit model, as specified below:

where

encompasses both objective and perceived financial literacy measures.

Second, we model the probability of capital market participation using a binary logit model:

where

is the logistic cumulative distribution function,

is financial literacy, and

is the vector of control variables.

To test for mediation (H2a), we adopt a causal steps approach (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Evidence of mediation is established if: (i) financial literacy significantly affects participation in a baseline model (H1); (ii) financial literacy significantly affects the proposed mediator, financial resilience; and (iii) the inclusion of financial resilience in the participation model attenuates the coefficient of financial literacy while resilience itself remains significant.

To test H2b regarding the relative power of perceived knowledge, we compare the coefficients and significance levels of objective and perceived financial literacy when both are included in the participation model. A substantial attenuation of the objective literacy coefficient alongside a strong, significant coefficient for perceived literacy would support H2b.

4.3.3. Testing the Moderated Relationships (H3)

Hypothesis H3 posits that sociodemographic conditions moderate the direct relationship between literacy and participation. To test this, we employ a moderated mediation analysis using the conditional process framework (Hayes, 2018). This involves testing for interaction effects between the independent variable (financial literacy) and the proposed moderators (e.g., income, education) in the participation equation. We estimate models with interaction terms to determine if the strength of the direct effect of literacy on participation is conditional on these sociodemographic factors.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and the Evolution of Financial Literacy

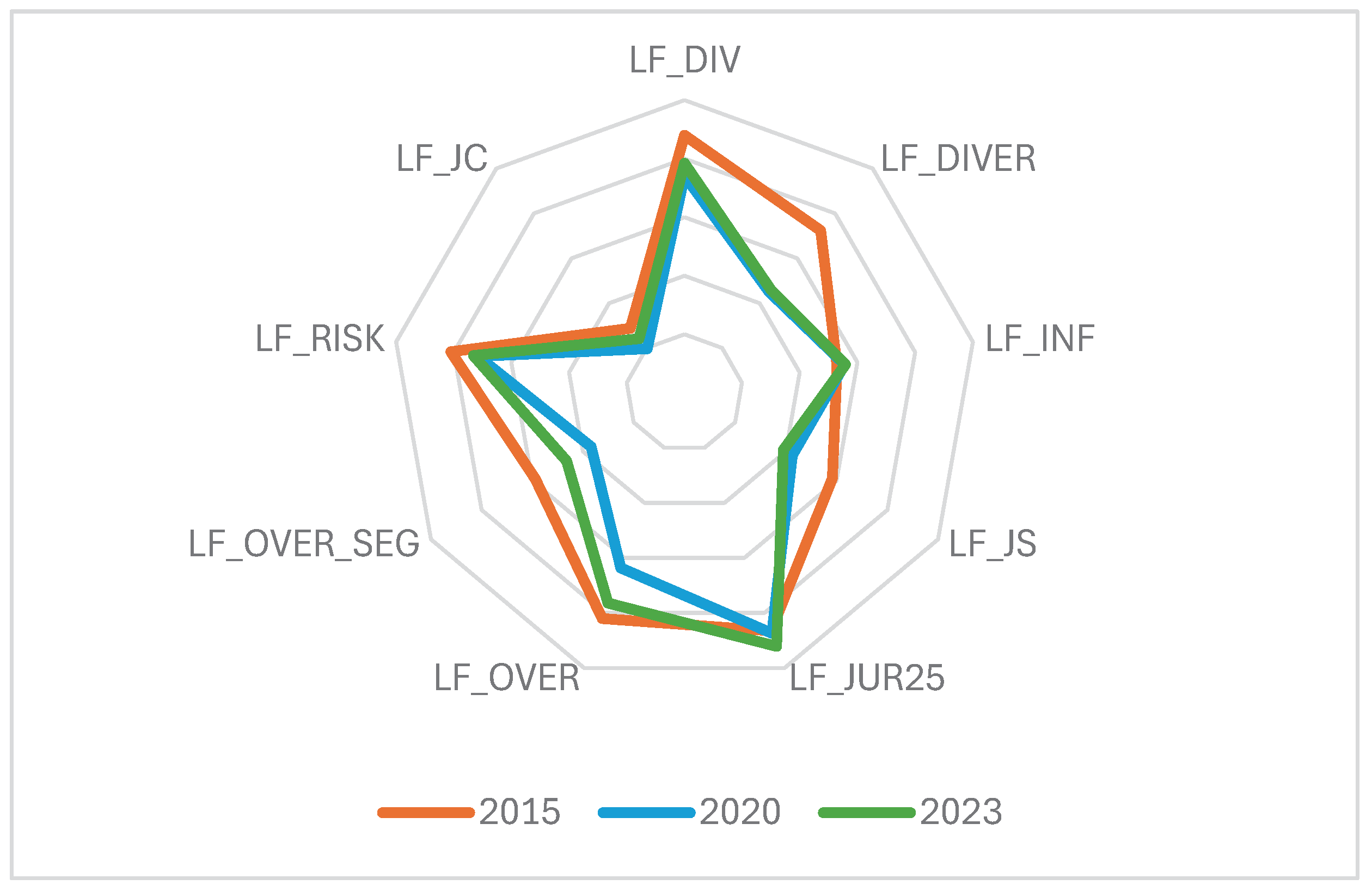

Our analysis begins by establishing the foundational context of financial literacy in Portugal across the three survey waves. The data reveals a concerning trajectory. As detailed in

Table 1 and

Table 2, and in

Figure 1, the average percentage of correct answers fell sharply from 67.6% in 2015 to 55.2% in 2020, with only a partial recovery to 59.1% in 2023. This indicates a significant decline in objective financial knowledge among the Portuguese population during this period. Understanding compound interest (LF_JC) remained the most challenging topic, with correct answers plummeting to 19.7% in 2020 and recovering only marginally to 24.2% in 2023.

Multivariate analysis using a Negative Binomial count model (

Table 4) corroborates these trends and identifies key sociodemographic correlates (see also

Table 3). Controlling for a host of factors, we confirm that financial knowledge was significantly higher in the 2015 baseline. Furthermore, higher levels of education (Schooling_high: coef. = 0.217, p<0.01) and income (Income_high: coef. = 0.444, p<0.01) are strongly associated with a greater number of correct answers, aligning with human capital and resource-based theories. A notable gender gap persists, with women scoring significantly lower than men (Female: coef. = -0.111, p<0.01). Age exhibits a non-linear, inverted U-shaped relationship with financial knowledge, peaking around 47 years.

5.2. The Mediating Role of Financial Resilience (H2a) and the Non-Role of Overconfidence (H2b)

A core proposition of our theoretical framework is that financial literacy operates through the mechanism of financial resilience. The results from the ordered logit models in

Table 5 provide strong support for the first leg of this mediated pathway (H2a), but not for the role of overconfidence as a proxy for self-efficacy in building resilience (H2b).

We find that both objective and perceived financial literacy are potent predictors of financial resilience. In the full specification (

Table 5, column [

3]), which includes both literacy measures and interaction terms, the coefficients for high levels of objective literacy (FL - Objective - High: coef. = 0.599, p<0.01) and perceived literacy (FL - Perceived - High: coef. = 1.098, p<0.01) are positive, substantial, and statistically significant. Crucially, the magnitude of these coefficients increases with the level of knowledge, indicating that the marginal impact of literacy on resilience is greatest for the most knowledgeable and confident individuals. This finding confirms that financially literate households are better equipped to build the essential buffer that defines resilience.

However, when we include the

overconfidence variable in column [

4] of

Table 5, its coefficient is positive but lacks statistical significance. This indicates that a biased, overconfident self-assessment of one's knowledge does not contribute to building actual financial resilience. While financial literacy builds resilience, mere overconfidence does not. This result challenges a simplistic interpretation of H2b and suggests that the beneficial psychological mechanism is grounded in accurate self-efficacy, not miscalibrated confidence.

Furthermore, the interaction terms between income and objective financial literacy included in column [

3] (e.g.,

income-high x FL-objective-high) were found to be statistically insignificant (as noted in the table). This indicates that the process of converting financial knowledge into resilience is broadly similar across income groups. The "floor effect" (Bianchi, 2018) may not manifest in the

building of resilience from knowledge, but rather in the subsequent step of converting that resilience into investment, as explored next.

5.3. Direct and Mediated Effects on Market Participation (H1, H2a & H2b)

The binary logit models for capital market participation (

Table 6) allow us to test the direct effect of literacy (H1) and the mediating role of resilience (H2a) and self-efficacy (H2b) simultaneously. The results reveal a nuanced picture that underscores the importance of both material and psychological channels.

Results in

Table 6, column [

2], establish a significant direct effect of high objective financial literacy on participation (FL - Objective - High: coef. = 0.822, p<0.01), providing initial support for H1. However, when perceived financial literacy is introduced in the the model (

Table 9, column [

3]), its effect is overwhelmingly strong (FL - Perceived - High: coef. = 2.303, p<0.01), while the coefficient for high objective literacy attenuates considerably (coef. = 0.385, p<0.10). This suggests that confidence in one's knowledge may be a more immediate driver of investment behavior than knowledge alone, echoing the concept of self-efficacy outlined in H2b.

Most critically, when financial resilience is added to the model in column [

4], it exerts a significant positive influence on participation (Financial Resilience: coef. = 0.416, p<0.01). The introduction of this mediator further attenuates the coefficient for high objective literacy, which becomes statistically insignificant. This pattern of results—where the significant effect of the independent variable (objective literacy) is reduced upon the inclusion of the mediator (resilience)—is consistent with partial mediation, thereby supporting H2a. Financially resilient households are significantly more likely to participate in capital markets, and resilience accounts for a part of the total effect of financial literacy.

The inclusion of the

overconfident variable in the participation model (

Table 6, column [

4]) shows a non-significant coefficient. This indicates that, unlike generalized self-efficacy (captured by perceived knowledge), the specific bias of overconfidence does not directly drive market participation. This nuanced finding suggests that the psychological channel supporting H2b is more about confident competence than about overconfident miscalibration.

A striking finding is the significant negative coefficient for the 2023 wave (Year 2023: coef. = -0.743, p<0.01 in the final model), indicating a decline in market participation despite the slight recovery in financial knowledge and a reported increase in financial resilience (

Table 5). This underscores the complexity of the participation puzzle, suggesting that other macroeconomic or institutional factors not captured in our models may have suppressed investment activity during this period.

5.4. The Moderating Role of Sociodemographics (H3)

Our results provide robust evidence for the moderating role of sociodemographic factors, as hypothesized in H3, particularly in the direct link between literacy and participation.

The significant interaction terms in the participation model (

Table 6, column [

3]) are highly informative. As noted, the interactions

income-average x FL-objective-high and

income-average x FL-objective-average are statistically significant. This reveals that the direct effect of objective financial literacy on the probability of market participation is not uniform; it is significantly stronger for households with average income compared to the baseline (low-income) group. This provides direct empirical support for H3, demonstrating that income acts as a key boundary condition, enabling households to act upon their financial knowledge.

This finding, combined with the strong, standalone positive coefficients for high income and education across all models, demonstrates a dual role for socioeconomic status. Firstly, these resources are fundamental for acquiring financial knowledge (

Table 4). Secondly, and crucially, they act as a powerful moderator of the literacy-participation link. Highly educated, high-income households are not only more knowledgeable but are also significantly better positioned to convert that knowledge directly into market participation. This aligns perfectly with our theoretical expectation that structural enablers critically condition the pathway from literacy to behavior (Bianchi, 2018; Grohmann, 2018).

In summary, the empirical evidence supports a complex, multi-stage process. Financial literacy fosters capital market participation both directly and indirectly by building financial resilience. Perceived knowledge is a powerful direct driver. However, this entire pathway is not universal; the direct effect of knowledge on participation is profoundly shaped by a household's socioeconomic context, which facilitates or constrains the ability to act on knowledge. The journey from financial literacy to market participation is one that is paved not just with knowledge, but with resilience, confidence, and, crucially, the requisite socioeconomic resources.

6. Conclusion

This study set out to unravel the complex relationship between financial literacy and household participation in capital markets by proposing and testing a moderated mediation model in the context of Portugal. Leveraging a robust, multi-wave national survey, we move beyond the established direct correlation to illuminate the underlying mechanisms and boundary conditions.

Our findings confirm that the pathway from knowledge to action is neither simple nor universal. We demonstrate that financial literacy's influence on market participation is significantly channeled through the building of financial resilience. Literate households are better equipped to create a financial buffer, and this buffer, in turn, provides the security necessary to engage with risky assets. This identifies resilience not just as a desirable outcome but as a critical mediating mechanism in the household investment decision. Simultaneously, we find that perceived financial knowledge is an equally, if not more, powerful driver of participation than objective knowledge alone, underscoring the paramount role of behavioral factors and confidence.

However, these mechanisms are not equally accessible to all. The entire pathway is powerfully moderated by socioeconomic status. Higher income (especially) and education not only facilitate the acquisition of financial knowledge but also enable households to convert that knowledge directly into market participation. This finding highlights a potential vicious cycle: households with fewer resources are less able to act on their knowledge to access higher-return investments, potentially perpetuating wealth inequality.

These insights carry significant policy implications for Portugal's National Plan for Financial Education (PNFF) and similar initiatives elsewhere. Our results suggest that effective policy must be multi-pronged. While improving financial knowledge remains important, it is likely insufficient on its own. Policies must also directly target the building of financial resilience, particularly among vulnerable groups, through programs that encourage emergency savings and prudent debt management. Furthermore, strategies to boost participation should address the psychological dimension by fostering accurate financial self-efficacy and must work to dismantle the structural barriers that limit access for lower-income and less-educated households.

This study is not without limitations. The use of pooled cross-sectional data, while informative, prevents definitive causal claims. The measure of market participation is binary and does not capture the intensity or quality of investment. Future research could employ panel data to establish causality and explore the role of digital access and financial advice as additional moderators in the digital age.

In conclusion, the journey to deepening retail capital market participation is more complex than merely improving financial literacy. It requires building resilient households, fostering genuine confidence, and creating an inclusive financial ecosystem where knowledge can be translated into opportunity, regardless of a household’s starting point.

ISEG - Universidade de Lisboa, Department of Economics; UECE (Research Unit on Complexity and Economics); REM (Research in Economics and Mathematics). This work was supported by FCT, I.P., the Portuguese national funding agency for science, research and technology, under the Project UID/06522/2023.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the CMVM. The author is pleased to acknowledge the financial support from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia under the Project UIDB/04007/2020.

CICEE - Research Center In Economics & Business Sciences. The author did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ANNEX 1 – Financial Knowledge Questions

(FL_Div) - Imagine that 5 brothers are given a gift of 1,000 euros in total. If the brothers have to share the money equally, how much does each one get? (A: 200 euros)

(FL_Inf) - Now imagine that the brothers must wait for one year to get their share of the 1,000 euros. If the inflation rate stays at 2%, in one year’s time will they be able to buy: i) More than they could buy today; ii) The same that they could buy today; iii) Less than they could buy today.

(FL_J25) - You lend 25 euros to a friend, and he gives you the 25 euros back the next day. How much interest has he paid on this loan? (A: 0 euros)

(FL_Js) - Imagine that someone puts 100 euros into a savings account with an interest rate of 2% per year (assume that no fees or taxes apply). How much would be in the account at the end of the first year, once the interest payment is made? (A: 102 euros)

(FL_Jc) - And how much would be in the account at the end of five years? (Assume that no fees or taxes are charged and that at the end of each year you leave the amount of interest in that same savings account): i) More than 110 euros; ii) Exactly 110 euros; iii) Less than 110 euros; iv) Impossible to tell from the information given.

(FL_RiskRet) - Please tell me if the following statement is true or false: “An investment with a high return is likely to be high risk” (A: True)

(FL_Diver) - Please tell me if the following statement is true or false: “It is usually possible to reduce the risk of investing in the stock market by buying a wide range of shares” (A: True)

(FL_Over) - Please, to look at the following statement of a current account.

| Current account – Bank statement on 20 April 20aa |

€ |

| Date |

Description |

Amount |

Balance |

| |

Previous balance |

|

110.00 |

| 24-03-20aa |

ATM withdrawal |

-60.00 |

50.00 |

| 30-03-20aa |

Salary transfer |

1,200.00 |

1,250.00 |

| 01-04-20aa |

Transfer to a time deposit |

-120.00 |

1,130.00 |

| 02-04-20aa |

Home loan instalment |

-525.00 |

605.00 |

| 03-04-20aa |

Mobile phone |

-40.00 |

565.00 |

| 08-04-20aa |

Supermarket |

-210.00 |

355.00 |

| 12-04-20aa |

Electricity |

-60.00 |

295.00 |

| 13-04-20aa |

Restaurant |

-40.00 |

255.00 |

| 16-04-20aa |

Bank check |

-70.00 |

185.00 |

| 18-04-20aa |

ATM withdrawal |

-50.00 |

135.00 |

| 20-04-20aa |

XPT petrol station |

-35.00 |

100.00 |

| |

Available balance |

|

100.00 |

| |

Authorized balance |

|

1,060.00 |

According to this statement, what is the balance of the current account that can be used on 20 April 20aa without resorting to a bank overdraft? i) 110 euros; ii) 100 euros; iii) 1,060 euros; iv) 1,160 euros.

- 9.

(FL_OverSeg) - Suppose that on 21 April 20aa your car insurance of 250 euros will be debited. Does your account have sufficient balance to cover this payment? i) No; ii) Yes, but the account will be overdrawn by 150 euros; iii) Yes, the account has enough money and there is no need to resort to an overdraft; iv) Yes, but the account will be overdrawn by 250 euros.

(Correct answers in bold).

ANNEX 2 – Definition of Variables

| Marital status - Married |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent is married |

| Age |

Age of respondent, in years |

| Occupation - Active |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent is a worker (self-employed or employee) or unemployed but looking for work |

| Income |

|

| |

High |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the household's net monthly income is above 2,500€ |

| |

Average |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the household's net monthly income is below 2,500€, but is higher than 1,000€ |

| Schooling - High |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent concluded at least a university degree |

| Gender - Female |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent is a woman |

| Financial Literacy (FL) |

|

| |

Objective |

Number of correct answers to the FL questions |

| |

Objective - High |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the number of correct answers to the 9 financial literacy questions is 7, 8 or 9 |

| |

Objective - Average |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the number of correct answers to the 9 financial literacy questions is 4, 5 or 6 |

| Perceived |

Equal to 1, if the respondent indicates that his/her knowledge of subjects related to financial markets and products is well below the average for the Portuguese population; 2, if they indicate that it is below average; 3, if it is equal to the average; 4, if they indicate that it is above average; and 5, if they indicate that it is well above average |

| Perceived - High |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if FL Perceived > 3 |

| Perceived - Average |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if FL Perceived = 3 |

| Year |

|

| 2015 |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the wave of the survey is 2015. |

| 2020 |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the wave of the survey is 2020. |

| 2023 |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the wave of the survey is 2023. |

| Region |

|

| Alentejo |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent lives in Alentejo |

| Algarve |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent lives in Algarve |

| Center |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent lives in the Center region |

| Lisbon |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent lives in the Lisbon region |

| North |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent lives in the North region |

| Town |

|

| Big |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent lives in a city with 100,000 or more inhabitants |

| Middle |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent lives in a town with more than 5,000 but less than 100,000 inhabitants |

| Participation |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if the respondent has stocks, or bonds or mutual funds in the portfolio |

| Financial resilience |

Equal to 1 if the answer to the question “If you lost your main source of income, how long could you continue to cover your living expenses, without borrowing any money or moving house?” is “less than a week”; 2 is the answer is “at least a week, but less than a month”; 3 if the answer is “at least a month, but less than 3 months”; 4 if the answer is “at least 3 months, but less than 6 months”; and 5 if the answer is “more than 6 months” |

| Number of correct answers |

FL Objective |

| Underconfident |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if FL_Objective is higher than FL_Perceived |

| Overconfident |

Binary variable, equal to 1 if FL_Objective is lower than FL_Perceived |

| Confidence |

Equal to -1 if Underconfident=1, 0 if Underconfident=0 and Overconfident=0, 1 if Overconfident=1 |

ANNEX 3 – Confidence

Table A3.1.

Objective versus perceived knowledge.

Table A3.1.

Objective versus perceived knowledge.

| |

|

Objective knowledge * |

| |

|

Low |

Average |

High |

All |

| |

|

# |

% |

# |

% |

# |

% |

# |

% |

| Perceived knowledge ** |

Very high |

1 |

0.0% |

8 |

0.2% |

27 |

0.7% |

36 |

0.9% |

| High |

15 |

0.4% |

89 |

2.3% |

189 |

4.9% |

293 |

7.6% |

| Average |

237 |

6.1% |

914 |

23.7% |

877 |

22.7% |

2028 |

52.6% |

| Low |

378 |

9.8% |

485 |

12.6% |

172 |

4.5% |

1035 |

26.8% |

| Very low |

274 |

7.1% |

152 |

3.9% |

37 |

1.0% |

463 |

12.0% |

| All |

905 |

23.5% |

1,648 |

42.7% |

1,302 |

33.8% |

3,855 |

100.0% |

Table A3.2.

Overconfidence and underconfidence.

Table A3.2.

Overconfidence and underconfidence.

| |

2015 |

2020 |

2023 |

ALL |

| |

# |

% |

# |

% |

# |

% |

# |

% |

| Overconfident |

99 |

9.3% |

178 |

13.4% |

73 |

5.0% |

350 |

8.5% |

| Underconfident |

466 |

43.9% |

488 |

36.8% |

769 |

52.4% |

1,723 |

41.9% |

Table A3.3.

Confidence – ordered logit model.

Table A3.3.

Confidence – ordered logit model.

| Year_2015 |

0,422 |

*** |

| |

(5,15) |

|

| Year_2020 |

0,766 |

*** |

| |

(10,23) |

|

| Married |

-0,047 |

|

| |

(0,65) |

|

| Schooling_high |

-0,322 |

*** |

| |

(3,62) |

|

| Age |

-0,026 |

** |

| |

(2,46) |

|

| Age x Age |

0,000 |

*** |

| |

(3,42) |

|

| Income_high |

0,340 |

** |

| |

(2,30) |

|

| Income_average |

0,089 |

|

| |

(0,84) |

|

| Female |

0,235 |

*** |

| |

(3,62) |

|

| Occupation_active |

-0,069 |

|

| |

(0,85) |

|

| Region_Alentejo |

-0,505 |

** |

| |

(2,56) |

|

| Region_Algarve |

-0,010 |

|

| |

(0,05) |

|

| Region_Center |

-0,112 |

|

| |

(0,66) |

|

| Region_Lisbon |

-0,779 |

*** |

| |

(4,61) |

|

| Region_North |

-0,143 |

|

| |

(0,88) |

|

| Town_big |

0,110 |

|

| |

(1,17) |

|

| Town_middle |

-0,118 |

|

| |

(1,54) |

|

References

- Abreu, M. and V. Mendes (2012). Information, overconfidence and trading: Do the sources of information matter? Journal of Economic Psychology 33(4): 868-881. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S., Qian, W., & Tan, R. (2020). *Household finance: A functional approach*. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). *Self-efficacy: The exercise of control*. W. H. Freeman.

- Barrafrem, K., Tinghög, G., & Västfjäll, D. (2024). Behavioral and contextual determinants of different stages of saving behavior. *Frontiers in Behavioral Economics*, *3*, 1381080. [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. *Journal of Personality and Social Psychology*, *51*(6), 1173–1182. [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. (1993). *Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education* (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Bianchi, M. (2018). Financial literacy and portfolio dynamics. *The Journal of Finance*, *73*(2), 831–859. [CrossRef]

- Byegon, G. (2020). Linkage between self-control, financial innovations and financial inclusion: A moderated mediation analysis across levels of financial literacy. *European Journal of Business and Management Research*, *5*(4), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. Y. (2006). Household finance. *The Journal of Finance*, *61*(4), 1553–1604. [CrossRef]

- Changwony, F. K., Campbell, K., & Tabner, I. T. (2021). Savings goals and wealth allocation in household financial portfolios. *Journal of Banking & Finance*, *124*, 106028. [CrossRef]

- Christelis, D., Jappelli, T., & Padula, M. (2010). Cognitive abilities and portfolio choice. *European Economic Review*, *54*(1), 18–38. [CrossRef]

- Claus, E., & Dedewanou, F. (2024). Learning, expectations, and household finance. *Journal of Monetary Economics*, *145*, 103536. [CrossRef]

- Cocco, J. F., Gomes, F. J., & Maenhout, P. J. (2005). Consumption and portfolio choice over the life cycle. *The Review of Financial Studies*, *18*(2), 491–533. [CrossRef]

- Curry, T. (2025). Modeling the dynamic interplay between financial literacy, resilience, and emotional well-being. *Cogent Economics & Finance*, *13*(1), e2544177. [CrossRef]

- Enders, Z., Hünnekes, F., & Müller, G. J. (2022). Monetary policy, firm heterogeneity, and customer markets. *Journal of Monetary Economics*, *125*, 112–129. [CrossRef]

- Erdem, D., & Rojahn, J. (2022). The influence of financial literacy on financial resilience: New evidence from Europe during the COVID-19 crisis. *Managerial Finance*, *48*(9/10), 1453–1471. [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Mejia, C., Mejía, D. & Córdoba, P. (2023). Financial literacy and financial wellbeing: Evidence from Peru and Uruguay. Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing 1: 403–429. [CrossRef]

- Evans, G. W., & Honkapohja, S. (2001). *Learning and expectations in macroeconomics*. Princeton University Press.

- Feng, X., Lu, B., Song, X., & Ma, S. (2019). Financial literacy and household finances: A Bayesian two-part latent variable modeling approach. *Journal of Empirical Finance*, *51*, 119–137. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2014). Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. *Management Science*, *60*(8), 1861–1883. [CrossRef]

- Gollier, C. (2002). What does classical theory have to say about household portfolios? In L. Guiso, M. Haliassos, & T. Jappelli (Eds.), *Household portfolios* (pp. 27–54). MIT Press.

- Gomes, F., Haliassos, M., & Ramadorai, T. (2021). Household finance. *Journal of Economic Literature*, *59*(3), 919–1000. [CrossRef]

- Grable, J. E., Britt, S. L., & Webb, F. J. (2008). Environmental and biopsychosocial profiling of risk tolerance. *Journal of Behavioral Finance*, *9*(2), 90–104. [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, A. (2018). Financial literacy and financial behavior: Evidence from the emerging Asian middle class. *Pacific-Basin Finance Journal*, *48*, 129–143. [CrossRef]

- Hasler, A., Lusardi, A., & Oggero, N. (2018). *Financial fragility in the US: Evidence from the National Financial Capability Study*. Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center. https://gflec.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Financial-Fragliness-Research-Paper-04-16-2018-Final.pdf.

- Hastings, J. S., Madrian, B. C., & Skimmyhorn, W. L. (2013). Financial literacy, financial education, and economic outcomes. *Annual Review of Economics*, *5*, 347–373. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). *Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach* (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Hsu, Y.-L., Chen, H.-L., Huang, P.-K., & Lin, W.-Y. (2021). Does financial literacy mitigate gender differences in investment behavioral bias? *Finance Research Letters*, *41*, 101789. [CrossRef]

- Hubar, S., Koulovatianos, C., & Li, J. (2020). The role of labor-income risk in household risk-taking. *European Economic Review*, *129*, 103522. [CrossRef]

- Kaustia, M., Conlin, A., & Luotonen, N. (2023). What drives stock market participation? The role of institutional, traditional, and behavioral factors. *Journal of Banking & Finance*, *148*, 106743. [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L., & Lusardi, A. (2020). Financial literacy and financial resilience: Evidence from around the world. *Financial Management*, *49*(3), 589–614. [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., & Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). *Financial literacy around the world*. Standard & Poor's Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey.

- Kumar, P., Pillai, R., Kumar, N., & Tabash, M. I. (2023). The interplay of skills, digital financial literacy, capability, and autonomy in financial decision making and well-being. *Borsa Istanbul Review*, *23*(1), 169–183. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Chen, J.-K., & Xiao, J. J. (2025). Financial resilience: A scoping review, conceptual synthesis and theoretical framework. *International Journal of Bank Marketing*. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. *Journal of Economic Literature*, *52*(1), 5–44. [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2023). The importance of financial literacy: Opening a new field. *Journal of Economic Perspectives*, *37*(4), 137–154. [CrossRef]

- Ndou, A. (2023). The moderator effect of socioeconomic status on the relationship between parental financial teaching and financial literacy. *International Journal of Applied Economics, Finance and Accounting*, *17*(2), 90–103. [CrossRef]

- North, D. C. (1990). *Institutions, institutional change and economic performance*. Cambridge University Press.

- Oehler, A., & Horn, M. (2023). Households' decision on capital market participation: What are the drivers? A multi-factor contribution to the participation puzzle. *Financial Services Review*, *31*(4), 283–305. [CrossRef]

- Sent, E.-M. (2018). Rationality and bounded rationality: You can't have one without the other. *The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought*, *25*(6), 1370–1386. [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. A. (1997). *An empirically based microeconomics*. Cambridge University Press.

- Tahir, M. S., Ahmed, A. D., & Richards, D. W. (2021). Financial literacy and financial well-being of Australian consumers: A moderated mediation model of impulsivity and financial capability. *International Journal of Bank Marketing*, *39*(7), 1377–1394. [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2011). Financial literacy and stock market participation. *Journal of Financial Economics*, *101*(2), 449–472. [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2012). Financial literacy, retirement planning and household wealth. *The Economic Journal*, *122*(560), 449–478. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. J., & O'Neill, B. (2018). Propensity to plan, financial capability, and financial satisfaction. *International Journal of Consumer Studies*, *42*(5), 501–512. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Yang, Z., Ali, S. T., Li, Y., & Cui, J. (2022). Does financial literacy affect household financial behavior? The role of limited attention. *Frontiers in Psychology*, *13*, 906153. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).