1. Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common skin cancer worldwide. Its incidence has been increasing in parallel with population aging, particularly among individuals aged ≥65 years [

1,

2]. Striking geographic and ethnic disparities exist: the incidence is 270 per 100,000 person-years in Australia [

3] but remains significantly lower in East Asia (e.g., approximately 3–4 per 100,000 in Japan) [

4]. However, rapidly aging societies in East Asia are now experiencing a disproportionate increase in disease burden; for instance, the incidence of cSCC nearly doubled between 1999 and 2019 [

5].

In Japan, nationwide registry data have confirmed that cSCC accounts for approximately 44% of all skin cancers, with a particularly sharp increase among the older population [

4]. Furthermore, clinical data have demonstrated that patients aged ≥90 years represent a substantial and growing subgroup: in a multicenter surgical series, one-third of all cSCC cases occurred in nonagenarians, who exhibited significantly higher recurrence risk despite standard treatment [

6]. Although cSCC generally has a lower case-fatality rate than that of melanoma, its burden in older adults is substantial; for example, the disability-adjusted life-year rate in the 70–74-year age group is approximately 74.59 per 100,000 population, underscoring its significant impact in aging societies [

7]. These epidemiological observations highlight the urgent need to adapt cSCC management strategies to the realities of super-aged societies, particularly in East Asia, while recognizing the regional and ethnic disparities in incidence and outcomes. Therefore, a deeper understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying cSCC development is essential. In particular, age-associated changes in the immune system, commonly referred to as immunosenescence, play a critical role in both the pathogenesis of cSCC and the response to emerging therapies, such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors. Accordingly, this review focuses on the age- and region-specific challenges of cSCC management in older patients in East Asia, with a particular emphasis on frailty, comorbid conditions, and the safe use of immunotherapy in Japan’s super-aged society, where local data remain limited.

2. Biology and Risk Factors Relevant to Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma (cSCC) in the Older Population

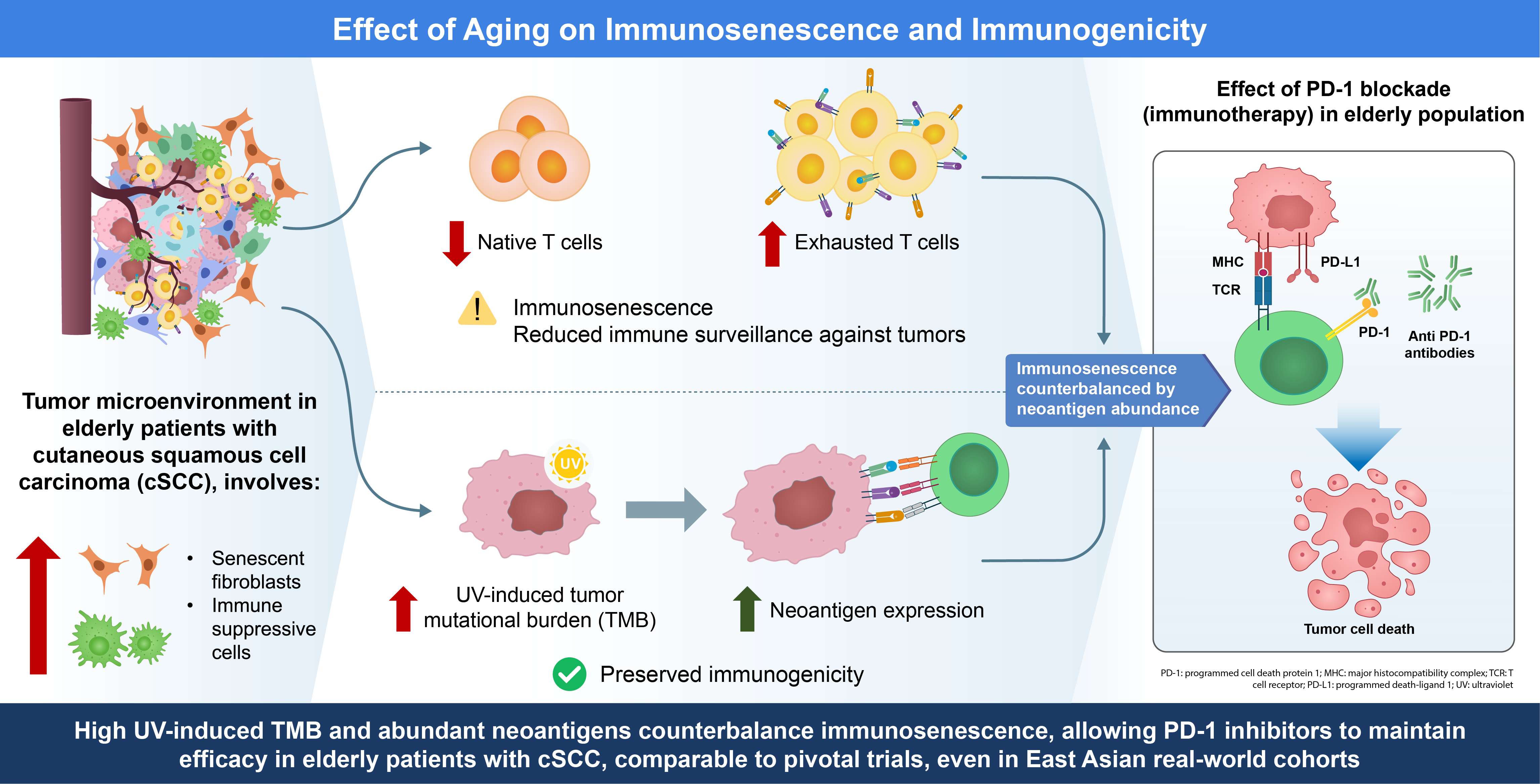

cSCC predominantly affects older adults, and the aging immune system (“immunosenescence”) can influence both tumor behavior and treatment outcomes. Immunosenescence is the progressive decline in immune function with age and is characterized by systemic changes that foster tumor immune evasion [

8]. This section explores key age-related immunological changes, including T-cell dysfunction, altered antigen presentation, accumulation of suppressive cells, and inflammatory shifts, and how they affect the efficacy and safety of PD-1 inhibitor immunotherapy in cSCC. We draw on evidence from cSCC and related cancers to highlight the tumor microenvironment (TME) in older patients and the clinical outcomes of immune checkpoint blockade in older patients.

2.1. Immunosenescence: Age-Related Immune Changes

Aging is associated with broad immune remodeling, which can impair antitumor immunity. Thymic involution and bone marrow changes lead to reduced naive T-cell output, skewing toward memory and senescent T-cell populations [

9,

10,

11]. Thus, older individuals have fewer fresh T cells that respond to new antigens and more terminally differentiated or exhausted T cells. Aged T cells often upregulate inhibitory receptors, such as PD-1, T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3, and lymphocyte activation gene-3 [

12]. These age-related immune alterations may affect the responsiveness and toxicity profiles of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in older adults [

13], reflecting a state of chronic stimulation and T-cell exhaustion. Functionally, older T cells exhibit a diminished proliferative capacity and impaired cytotoxicity [

14]. In parallel, age-associated defects in antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including dendritic cells, result in reduced costimulatory activity, which may compromise the efficient priming of T-cell responses [

14]. The cytotoxic function of natural killer cells also declines with age [

14], further limiting the ability of the innate immune system to control tumors.

Immunosenescence is also marked by myeloid skewing of hematopoiesis, leading to increased production of myeloid cells at the expense of lymphoid cells [

15]. This can translate into higher levels of immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and M2-polarized macrophages in older individuals, which actively dampen T-cell responses in the TME [

16]. Additionally, aging tissues accumulate senescent cells (e.g., fibroblasts) that secrete pro-tumor and immunosuppressive factors, such as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. These factors (including interleukin [IL]-6, IL-1 family cytokines, tumor growth factor [TGF]-β) drive chronic low-grade inflammation, a phenomenon termed “inflammaging” [

16,

17]. Inflammaging sustains a proinflammatory milieu that paradoxically contributes to immune dysregulation, recruits immune cells in a dysfunctional manner, and promotes the accumulation of suppressive populations. For example, regulatory T cells (Tregs; CD4

+FOXP3

+), which restrain antitumor immunity, increase in frequency with age in mice and in certain human tissues [

18]. Conversely, the pool of antigen-specific effector T cells may be present in normal numbers in an aged host but fail to migrate into peripheral tissue efficiently. Notably, older individuals show impaired homing of circulating T cells to the skin [

19], undermining local tumor surveillance. Taken together, these changes—T-cell exhaustion, waning APC function, Treg/MDSC accumulation, and cytokine imbalances—create an immune landscape in older patients that can be tipped toward tumor tolerance and the evasion of immune surveillance.

2.2. Tumor Microenvironment in the Older Population

The TME in older patients with cSCC reflects intrinsic tumor factors and an aged host milieu. Chronic ultraviolet (UV) exposure, which is common in the older population, not only drives the high mutational burden of cSCC but also causes cumulative dermal damage and senescence in the surrounding stroma [

20]. Senescent fibroblasts in aged skin acquire a pro-inflammatory, pro-tumor phenotype: they secrete growth factors (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, vascular endothelial growth factor) and matrix-degrading enzymes that promote cancer cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and invasion. Tumor cells can “educate” resident fibroblasts into cancer-associated fibroblasts resembling senescent cells, suggesting that an aged stromal environment may be especially permissive for tumor progression [

20]. Moreover, TGF-β, often elevated in photoaged skin [

21], can suppress effective antitumor immunity [

16] and has been implicated in resistance to checkpoint inhibitors by excluding T-cell infiltration [

22]. In older patients with cSCC and related squamous cancers, the TME is often enriched with immunosuppressive elements, such as Tregs. Azzimonti et al. reported that Treg infiltration was greater in cSCC than in normal skin, with particularly high levels observed in moderately to poorly differentiated (more invasive) lesions. They also showed that aggressive SCC subtypes exhibited a reduced CD8+/Treg ratio, underscoring the association between Treg predominance and tumor aggressiveness [

23]. An aged TME may also show reduced T-cell trafficking; effector T lymphocytes in older individuals infiltrate the skin less efficiently, partly because of diminished endothelial adhesion molecule expression and altered chemokine signaling [

19], a phenomenon likely relevant to cSCC.

Despite these challenges, some aspects of the aging TME may paradoxically favor responses to immunotherapy. Chronic antigenic stimulation in the older population can lead to clonal expansion of certain T cells, including tumor-specific clones [

18], and cSCC tumors in older patients often harbor extremely high neoantigen loads because of UV-induced DNA damage [

24]. A high tumor mutational burden is associated with improved survival, and in some studies, greater responsiveness to PD-1 blockade [

25] suggests that the abundance of neoantigens may, at least in part, counterbalance age-related immune senescence. Additionally, although systemic Tregs increase with age, intratumoral Treg density is not necessarily higher in older patients. In melanoma, FOXP3

+ Tregs were found to be less abundant in tumors from older individuals compared with those from younger ones, resulting in a more favorable effector (CD8

+) to Treg ratio within the TME [

26]. This may reduce local immunosuppression and improve the efficacy of checkpoint inhibitors in older tumors. Overall, the aged cSCC microenvironment is a combination of heightened tumor antigenicity and immunosuppressive host factors. Understanding this balance is the key to predicting how PD-1 inhibitor therapy should be administered to geriatric patients.

3. Standard Local Therapies and Their Limits

cSCC is typically managed with local therapies, such as surgical excision, which is often curative for most primary tumors, and radiotherapy as an adjunct or alternative when surgery is not feasible. However, these local treatments have important limitations in a subset of patients. Although >90% of patients with cSCC exhibit relatively indolent behavior, a minority progress to advanced disease, locally extensive or metastatic, that cannot be adequately controlled by surgery or radiotherapy [

27]. High-risk tumors, such as large, deeply invasive lesions or those with perineural invasion, are associated with an increased risk of recurrence and metastasis [

28,

29]. Overall, approximately 5% of cSCC develop metastases [

28,

29]. In advanced cSCC, curative resection may be impossible or may be associated with unacceptable morbidity [

30]. Moreover, not all patients can tolerate aggressive surgery, particularly older individuals or those with significant comorbidities [

31,

32]. Although radiotherapy can improve local control or serve as the primary treatment for inoperable cases, it is generally insufficient when the disease is widespread or metastatic. These limitations are particularly pronounced in older patients for whom comorbidities, frailty, or reduced tolerance to surgery and radiotherapy often further restrict curative options. In such situations, local interventions alone are inadequate, and systemic therapy is necessary for disease control [

30,

33].

4. Systemic Treatment Strategies for Advanced cSCC

Until recently, systemic options for advanced cSCC were limited and generally ineffective. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy, often combined with 5-fluorouracil or taxanes, and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor cetuximab have historically been used off-label in cSCC, drawing on regimens for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [

34]. These approaches achieved only modest responses, with an overall response rate of approximately 20–30% and a median response duration of approximately 5 months, and were further constrained by short-lived responses and significant toxicity [

35]. Nevertheless, EGFR inhibition remains an option for patients who are ineligible for immunotherapy, such as transplant recipients or those with uncontrolled autoimmune diseases. In addition, ongoing translational research is exploring molecularly targeted approaches based on frequent alterations in pathways, such as NOTCH, MAPK, and PI3K in cSCC [

36,

37], although these remain investigational. Although PD-1 inhibitors have become the standard first-line therapy, targeted therapies retain a niche role and may expand as precision oncology advances.

Therefore, the current European guidelines recommend that treatment decisions for advanced cSCC be made in a multidisciplinary setting, explicitly weighing toxicity risks along with patient age, frailty, and comorbidities [

38]. More recently, ICIs, especially PD-1 inhibitors, have fundamentally changed this landscape. Given the high UV-induced mutational burden of cSCC and its association with impaired immune surveillance, PD-1 blockade is a biologically rational and clinically effective strategy [

39]. ICIs have markedly improved outcomes, with more favorable tolerability than that of prior systemic therapies.

4.1. Evidence from Clinical Trials

PD-1 inhibitors are currently established as standard systemic therapies for advanced or unresectable cSCC. In pivotal trials, cemiplimab achieved an objective response rate (ORR) of 41.1–50% with durable responses and 3–4-year survival >70% in advanced cSCC (both locally advanced and metastatic disease) [

33,

40,

41]. Pembrolizumab showed comparable efficacy, with ORRs of 35.2% (recurrent/metastatic) to 50% (locally advanced) and a median duration of response (DOR) not reached [

42,

43]. In the CARSKIN trial, pembrolizumab achieved an ORR of

42% in first-line unresectable disease, with a greater benefit in programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)-positive tumors [

42]. Pacmilimab, tested in a small cSCC cohort (n=14), showed an ORR of 36%, including one complete response; however, the DOR and survival outcomes were not evaluated (several ongoing responses >12 months) [

44]. Both cemiplimab and pembrolizumab demonstrated manageable safety, with grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events in 11–13.9% of patients.

Table 1 summarizes the key trials.

4.2. Insights from Real-World Evidence

Real-world cohorts provide complementary insights into the feasibility of using PD-1 inhibitors in broader patient populations. Across Europe, cemiplimab cohorts have confirmed ORRs of 32–76.7% and 1-year overall survival (OS) of approximately 60%, although tolerance was reduced in very older subgroups [

45,

46,

47,

48]. The US series also demonstrated activity, with ORRs 26.7–42.3% and responses linked to tumor mutational burden and head/neck primaries [

49,

50]. In Latin America, nivolumab produced an ORR of 58.3%, with no complete response; however, its feasibility has been demonstrated [

51]. In Australia, a large multicenter cohort (n=286; median age, 75.2 years) showed an ORR of 60% and a 1-year OS rate of 78%, including 31% immunocompromised patients; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) ≥2 was observed in 21% of the patients [

52]. A separate single-center study (n=53; median age, 81.8 years) reported an ORR of 57% (complete response, 33%) with a 1-year OS rate of 63% and confirmed worse outcomes in patients with ECOG PS ≥2 [

53]. Japanese data, although limited (n=14), showed an ORR of 57.1% and a 1-year OS rate of 73.1% [

54].

Table 2 summarizes regional real-world outcomes.

Taken together, these findings indicate that chronological age or comorbidity does not consistently diminish ICI efficacy in cSCC; rather, poor PS (ECOG PS ≥2) is the most consistent predictor of inferior survival.

5. Geriatric Oncology Principles in Practice

Older patients with cSCC often present with unique challenges that necessitate a geriatric oncology approach. Chronological age alone is a poor surrogate of a patient’s true physiological reserve [

55,

56]. Many patients in their 70s or 80s are robust and can tolerate therapy well, whereas others are frail, have a multidimensional state of decreased functional reserve, and are at a higher risk of adverse outcomes. Standard PS scores (ECOG PS or Karnofsky) often miss these nuances, as comprehensive geriatric assessments reveal hidden vulnerabilities even in “fit” older adults [

55,

56]. For example, 69% of older patients with cancer with normal PS had at least one deficit, commonly polypharmacy (≥9 drugs in 43%) or multiple comorbidities (≥4 in 25%) [

57]. These findings underscore that routine oncology evaluations may underestimate patient risk, and guidelines recommend geriatric screening for those aged ≥65 years starting systemic therapy. Assessing domains, such as function, comorbidities, cognition, nutrition, and social support, provides individualized care [

55,

56].

A critical implication of these hidden frailties is their impact on immunotherapy tolerance and safety. ICIs, such as anti-PD-1 antibodies, have become key systemic treatments for advanced cSCC, especially in older patients. Chronological age alone does not increase immune-related adverse events (irAEs) [

58,

59,

60]; instead, frailty and comorbidity drive outcomes. For instance, mild toxicities, such as diarrhea, may precipitate dehydration or kidney injury in frail octogenarians, and steroids for irAEs may trigger delirium or infection [

61,

62]. In real-world analyses, irAE incidence was comparable to trial data, but patients with ECOG PS ≥2 had worse survival [

53]. Similarly, frail patients with melanoma had higher hospitalization rates despite similar rates of grade ≥3 irAEs [

63].

Polypharmacy further amplifies risks, as >40% of older adults take ≥9 drugs daily, increasing the likelihood of adverse drug events and drug–drug interactions that require careful consideration when initiating immunotherapy [

57,

61]. Multidisciplinary coordination among geriatricians, pharmacists, and caregivers is crucial because even low-grade toxicities may require early intervention in patients with frailty.

Importantly, advanced age should not prevent patients with cSCC from receiving immunotherapy. Pivotal PD-1 trials enrolled many older adults (median age, 70s) and demonstrated ORRs of approximately 40–50% [

33,

64]. Real-world cohorts confirmed similar outcomes: ORRs were approximately 50% in a French expanded-access program [

46], approximately 60% in an Australian series [

52], and 76.7% in a frail Italian cohort [

48]. Responses were observed even in immunosuppressed patients, indicating that efficacy is preserved. The strongest predictor of survival is functional status; in France, the 1-year OS rate was 73% with ECOG PS 0–1 versus 36% with ECOG PS ≥2 [

46]. Similarly, US data showed that ECOG PS ≥3, not age ≥75 years, predicted worse survival [

65]. Thus, a fit 80-year-old may benefit as much as younger patients, whereas a frail counterpart may face a higher risk. The challenge is to identify the modifiable vulnerabilities and intervene accordingly.

Integrating geriatric principles, screening for vulnerabilities with tools, such as the Geriatric-8 (G8), optimizing comorbidities and medications, early irAE management, and aligning goals of care, maximizes benefits while minimizing harm [

66,

67,

68]. Shared decision-making is essential for tailoring therapy to patient priorities and balancing cure with palliation.

By applying these practices, clinicians can safely extend the advances in immunotherapy to a growing population of older patients with cSCC. Octogenarians and nonagenarians can achieve excellent outcomes if appropriately selected [

69]. This emphasis must remain on physiological rather than on chronological age [

70]. Tailoring care in this manner will ensure that advances in immunotherapy translate into real-world survival and quality-of-life gains for this vulnerable group.

6. Regional Perspectives: East Asia and Japan

As summarized in

Section 4.2, most real-world evidence to date has come from Europe, the United States, and Australia, where outcomes with PD-1 inhibitors closely mirror those observed in clinical trials. However, data from East Asia are limited. In Japan, early real-world experiences have recently been reported, demonstrating response rates and safety outcomes that are consistent with international trial data [

54]. These findings indicate that Japanese patients with cSCC respond to immunotherapy similarly to their Western counterparts, with no unexpected safety concerns.

6.1. Optimizing Treatment Sequences

The advent of ICIs has shifted treatment paradigms across East Asia. Historically, cytotoxic chemotherapy and EGFR inhibitors, such as cetuximab, were occasionally used in unresectable cSCC, but their antitumor activity was limited, with only modest response rates reported in international studies [

34,

71]. Given their limited efficacy, these targeted agents have been largely supplanted by ICIs as first-line systemic therapy. Consequently, current practice in Japan and elsewhere favors PD-1 inhibitors as initial therapy for advanced cSCC [

54]. Studies have explored how best to sequence or combine these modalities. The recent I-TACKLE study in Italy examined the effects of cetuximab after PD-1 inhibitor failure [

72]. This approach achieved a cumulative ORR of 63% using cetuximab to overcome pembrolizumab resistance and elicited responses in 10 of 23 resistant patients (43%). However, this sequential strategy comes at the expense of increased toxicity. EGFR blockade causes skin toxicities; in a phase II cetuximab monotherapy trial, 78% of patients developed an acneiform rash, generally grade 1–2 [

34]. Thus, although adding cetuximab may benefit a subset of ICI-refractory patients, clinicians should be mindful of the risk of rash and other EGFR-related adverse effects, which are often low grade and manageable in routine practice.

6.2. Tolerability and Unique Considerations in East Asian Populations

Overall, the available evidence indicates that East Asian patients tolerate immunotherapy, as well as Western patients. However, there are ethnic considerations. Certain irAEs may occur more frequently in Asian populations than in non-Asian populations. For example, interstitial lung disease and ICI-related pneumonitis have been reported relatively frequently in Japanese cohorts, which likely reflects a higher baseline risk of drug-induced interstitial lung disease in this population [

73]. Similarly, immune-related hepatitis, typically presenting as elevations in liver enzyme levels, requires particular vigilance in East Asia, where chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains highly prevalent and contributes to the risk background for irAEs; in Japan, attention is paid to HBV reactivation during ICI therapy [

74,

75].

In response to these risks, oncologists in Japan and neighboring countries carefully screen for latent infections and monitor hepatic function during ICI therapy. Importantly, these factors can be managed with proper precautions and do not preclude effective treatment. In practice, Japanese patients have tolerated ICIs well, with efficacy and safety outcomes comparable to those in Western trials and no new safety signals observed [

54]. This finding is consistent with the broader oncology experience, as studies in Asian lung cancer populations have also demonstrated outcomes similar to those in Caucasian patients [

73,

76]. In summary, the regional experience, albeit early, suggests that ICIs are transforming advanced cSCC care in East Asia, just as they have elsewhere. Japan has led regional adoption, reporting response rates on par with global benchmarks. Across East Asia, ICIs are increasingly used for cSCC, and although published data remain limited, there is no evidence of their reduced efficacy. Ongoing research and postmarketing surveillance will refine treatment strategies, but the current findings are encouraging: Japanese and East Asian patients can achieve excellent results with immunotherapy, validating its role as the first-line standard of care across diverse populations. These regional experiences underscore not only the comparable efficacy of immunotherapy in East Asia but also the need for continued refinement of treatment strategies. This naturally leads to broader questions about how cSCC management can evolve in the future, particularly in terms of predictive biomarkers, treatment sequencing, and the integration of geriatric principles into standard care.

7. Future Directions and Unmet Needs

One major direction is the development of predictive biomarkers to guide immunotherapy selection, as no robust markers, such as tumor mutational burden, PD-L1 status, or CD8

+ T-cell infiltration, have yet been established, despite the high immunogenicity of cSCC [

77]. Its tumor mutation burden is among the highest among all cancers, and PD-L1 is frequently expressed [

39,

77]. Evidence suggests that PD-L1-positive tumors have high response rates to PD-1 inhibitors, underscoring the need to validate these biomarkers in prospective studies [

42].

Another emerging strategy is neoadjuvant immunotherapy, which has achieved approximately 50% pathological complete response and 89% 1-year event-free survival in high-risk resectable cSCC, demonstrating remarkable efficacy and addressing the unmet needs in this setting [

78].

Recent phase III evidence also supports adjuvant PD-1 blockade after surgery for high-risk cSCC, indicating that perioperative immunotherapy may further improve long-term outcomes [

79].

Finally, integrating frailty tools and geriatric assessments into treatment planning is crucial for the predominantly older patients with cSCC [

67]; instruments, such as the G8 index, can predict treatment tolerability, including postoperative complications, and Japan-based initiatives advocate incorporating such geriatric assessments in clinical trials to optimize therapy for older patients with cSCC. Multidisciplinary collaboration between geriatric medicine and oncology is essential for optimizing care in super-aged societies, such as Japan.

8. Conclusion

In the context of aging societies, particularly in East Asia, where older patients represent a growing majority of cSCC cases, optimizing management requires careful consideration of regional characteristics and age-specific vulnerabilities. ICIs have fundamentally expanded the therapeutic landscape for cSCC, offering durable tumor control and improved survival, even in older patients who comprise the majority of cases in super-aged societies. Although surgery and radiotherapy remain indispensable curative modalities for early-stage diseases, their integration with systemic immunotherapy is essential for advanced or unresectable tumors. To maximize the benefits of immunotherapy in older populations, the incorporation of geriatric oncology principles, particularly structured assessments of frailty, comorbidities, and polypharmacy, should be prioritized in clinical practice and research. In East Asia, Japan in particular, the accumulation of regional real-world evidence and consideration of unique healthcare and socioeconomic factors will be key to refining treatment strategies. Establishing multidisciplinary frameworks that link dermatology, oncology, and geriatric medicine is crucial for optimizing outcomes and adapting cSCC management to the realities of aging societies worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.; methodology, S.M.; validation, S.M.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M. and K.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and K.F.; writing—review and editing, S.M., K.F., and M.A.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by NHO Kagoshima Medical Center.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA), a generative AI tool, to assist in drafting portions of the manuscript. All AI-generated content was reviewed, edited, and approved by the authors. No AI tools were used to generate, analyze, or interpret the research data.

Conflicts of Interest

Shigeto Matsushita has received honoraria from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Bristol Myers Squibb. The other authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICIs |

immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| PD-1 |

programmed cell death protein 1 |

| MDSCs |

myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| TME |

tumor microenvironment |

| IL |

interleukin |

| TGF |

tumor growth factor |

| Tregs |

regulatory T cells |

| APCs |

antigen-presenting cells |

| UV |

ultraviolet |

| EGFR |

epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ORR |

objective response rate |

| DOR |

duration of response |

| OS |

overall survival |

| ECOG |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| PS |

performance status |

| irAEs |

immune-related adverse events |

| HBV |

hepatitis B virus |

| PD-L1 |

programmed death-ligand 1 |

| G8 |

Geriatric-8 |

References

- Lai, V.; Cranwell, W.; Sinclair, R. Epidemiology of skin cancer in the mature patient. Clin Dermatol 2018, 36, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.C.; Jin, A.; Koh, W.P. Trends of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma among the Chinese, Malays, and Indians in Singapore from 1968–2016. JAAD Int 2021, 4, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandeya, N.; Olsen, C.M.; Whiteman, D.C. The incidence and multiplicity rates of keratinocyte cancers in Australia. Med J Aust 2017, 207, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, D.; Namikawa, K.; Nakano, E.; Fujimori, M.; Uchitomi, Y.; Higashi, T.; Yamazaki, N.; Kawai, A. Epidemiology of skin cancer based on Japan’s National Cancer Registry 2016–2017. Cancer Sci 2023, 114, 2986–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.H.; Choi, S.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, S.S.; Jue, M.S.; Seo, S.H.; Park, J.; Roh, M.R.; Mun, J.H.; Kim, J.Y.; et al. Incidence and survival rates of primary cutaneous malignancies in Korea, 1999–2019: a nationwide population-based study. J Dermatol 2024, 51, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito-Sasaki, N.; Aoki, M.; Fujii, K.; Yamamura, K.; Hitaka, T.; Hirano, Y.; Nishihara, K.; Fujino, Y.; Matsushita, S. Age over 90 years is an unfavorable prognostic factor for resectable cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol 2025, 52, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Tang, B.; Guo, Y.; Cai, Y.; Li, Y.Y. Global burden of non-melanoma skin cancers among older adults: a comprehensive analysis using machine learning approaches. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 15266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yang, X.; Feng, Y.; Wu, L.; Ma, W.; Ding, G.; Wei, Y.; Sun, L. The impact of immunosenescence on the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma patients: a meta-analysis. Onco Targets Ther 2018, 11, 7521–7527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, L.; Eaton, S.M.; Burns, E.M.; Randall, T.D.; Swain, S.L. CD4 T cell memory derived from young naive cells functions well into old age, but memory generated from aged naive cells functions poorly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 15053–15058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saule, P.; Trauet, J.; Dutriez, V.; Lekeux, V.; Dessaint, J.P.; Labalette, M. Accumulation of memory T cells from childhood to old age: central and effector memory cells in CD4(+) versus effector memory and terminally differentiated memory cells in CD8(+) compartment. Mech Ageing Dev 2006, 127, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, E.J.; Ahmed, M.; Lanzer, K.; Randall, T.D.; Woodland, D.L.; Blackman, M.A. Age-associated decline in T cell repertoire diversity leads to holes in the repertoire and impaired immunity to influenza virus. J Exp Med 2008, 205, 711–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.S.; Burton Sojo, G.; Sun, H.; Friedland, B.N.; McNamara, M.E.; Schmidt, M.O.; Wellstein, A. The role of aging and senescence in immune checkpoint inhibitor response and toxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.; Charmsaz, S.; Tsai, H.L.; Aziz, K.; Shu, D.H.; Munjal, K.; Griffin, E.; Leatherman, J.M.; Lipson, E.J.; Ged, Y.; et al. Age-related divergence of circulating immune responses in patients with solid tumors treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruver, A.L.; Hudson, L.L.; Sempowski, G.D. Immunosenescence of ageing. J Pathol 2007, 211, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainciburu, M.; Ezponda, T.; Berastegui, N.; Alfonso-Pierola, A.; Vilas-Zornoza, A.; San Martin-Uriz, P.; Alignani, D.; Lamo-Espinosa, J.; San-Julian, M.; Jimenez-Solas, T.; et al. Uncovering perturbations in human hematopoiesis associated with healthy aging and myeloid malignancies at single-cell resolution. Elife 2023, 12, e79363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Wu, B.; Feng, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, W. Aging microenvironment and antitumor immunity for geriatric oncology: the landscape and future implications. J Hematol Oncol 2023, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Bonafè, M.; Valensin, S.; Olivieri, F.; De Luca, M.; Ottaviani, E.; De Benedictis, G. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000, 908, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynor, J.; Lages, C.S.; Shehata, H.; Hildeman, D.A.; Chougnet, C.A. Homeostasis and function of regulatory T cells in aging. Curr Opin Immunol 2012, 24, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, E.; Lacy, K.E.; Vukmanovic-Stejic, M.; Jagger, A.L.; Papageorgiou, A.P.; Hall, S.; Reed, J.R.; Curnow, S.J.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Buckley, C.D.; et al. Decreased TNF-alpha synthesis by macrophages restricts cutaneous immunosurveillance by memory CD4+ T cells during aging. J Exp Med 2009, 206, 1929–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arino, A.; Caputo, S.; Eibenschutz, L.; Piemonte, P.; Buccini, P.; Frascione, P.; Bellei, B. Skin cancer microenvironment: what we can learn from skin aging? Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 14043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.J.; Wang, Z.Q.; Datta, S.C.; Varani, J.; Kang, S.; Voorhees, J.J. Pathophysiology of premature skin aging induced by ultraviolet light. N Engl J Med 1997, 337, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariathasan, S.; Turley, S.J.; Nickles, D.; Castiglioni, A.; Yuen, K.; Wang, Y.; Kadel, E.E., III; Koeppen, H.; Astarita, J.L.; Cubas, R.; et al. TGFbeta attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature 2018, 554, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzimonti, B.; Zavattaro, E.; Provasi, M.; Vidali, M.; Conca, A.; Catalano, E.; Rimondini, L.; Colombo, E.; Valente, G. Intense Foxp3+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell infiltration is associated with high-grade cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and counterbalanced by CD8+/Foxp3+ CD25+ ratio. Br J Dermatol 2015, 172, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inman, G.J.; Wang, J.; Nagano, A.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Purdie, K.J.; Taylor, R.G.; Sherwood, V.; Thomson, J.; Hogan, S.; Spender, L.C.; et al. The genomic landscape of cutaneous SCC reveals drivers and a novel azathioprine associated mutational signature. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, W.; Zaretsky, J.M.; Sun, L.; Song, C.; Moreno, B.H.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Berent-Maoz, B.; Pang, J.; Chmielowski, B.; Cherry, G.; et al. Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell 2016, 165, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugel, C.H., 3rd; Douglass, S.M.; Webster, M.R.; Kaur, A.; Liu, Q.; Yin, X.; Weiss, S.A.; Darvishian, F.; Al-Rohil, R.N.; Ndoye, A.; et al. Age correlates with response to anti-PD1, reflecting age-related differences in intratumoral effector and regulatory T-cell populations. Clin Cancer Res 2018, 24, 5347–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.; Lammerts, M.U.P.A.; Genders, R.E.; Bouwes Bavinck, J.N. Update of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022, 36 Suppl 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmults, C.D.; Karia, P.S.; Carter, J.B.; Han, J.; Qureshi, A.A. Factors predictive of recurrence and death from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a 10-year, single-institution cohort study. JAMA Dermatol 2013, 149, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karia, P.S.; Morgan, F.C.; Ruiz, E.S.; Schmults, C.D. Clinical and incidental perineural invasion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and pooled analysis of outcomes data. JAMA Dermatol 2017, 153, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigos, A.J.; Garbe, C.; Dessinioti, C.; Lebbe, C.; Bataille, V.; Bastholt, L.; Dreno, B.; Concetta Fargnoli, M.; Forsea, A.M.; Frenard, C.; et al. European interdisciplinary guideline on invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: part 2. Treatment. Eur J Cancer 2020, 128, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Work Group; Invited Reviewers; Kim, J.Y.S.; Kozlow, J.H.; Mittal, B.; Moyer, J.; Olenecki, T.; Rodgers, P. Guidelines of care for the management of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018, 78, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansai, S.I.; Umebayashi, Y.; Katsumata, N.; Kato, H.; Kadono, T.; Takai, T.; Namiki, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Soejima, T.; Koga, H.; et al. Japanese Dermatological Association Guidelines: outlines of guidelines for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma 2020. J Dermatol 2021, 48, e288–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migden, M.R.; Rischin, D.; Schmults, C.D.; Guminski, A.; Hauschild, A.; Lewis, K.D.; Chung, C.H.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Lim, A.M.; Chang, A.L.S.; et al. PD-1 blockade with cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maubec, E.; Petrow, P.; Scheer-Senyarich, I.; Duvillard, P.; Lacroix, L.; Gelly, J.; Certain, A.; Duval, X.; Crickx, B.; Buffard, V.; et al. Phase II study of cetuximab as first-line single-drug therapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Clin Oncol 2011, 29, 3419–3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, C.; Kubicki, S.; Nguyen, Q.B.; Aboul-Fettouh, N.; Wilmas, K.M.; Chen, O.M.; Doan, H.Q.; Silapunt, S.; Migden, M.R. Advances in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma management. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, A.P.; Purdie, K.J.; Watt, S.A.; Haldenby, S.; den Breems, N.; Dimon, M.; Arron, S.T.; Kluk, M.J.; Aster, J.C.; McHugh, A.; et al. NOTCH1 mutations occur early during cutaneous squamous cell carcinogenesis. J Invest Dermatol 2014, 134, 2630–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, C.R.; Zhou, J.H.; Lee, J.J.; Drummond, J.A.; Peng, S.A.; Saade, R.E.; Tsai, K.Y.; Curry, J.L.; Tetzlaff, M.T.; Lai, S.Y.; et al. Mutational landscape of aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014, 20, 6582–6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigos, A.J.; Garbe, C.; Dessinioti, C.; Lebbe, C.; van Akkooi, A.; Bataille, V.; Bastholt, L.; Dreno, B.; Dummer, R.; Fargnoli, M.C.; et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: part 2. Treatment-update 2023. Eur J Cancer 2023, 193, 113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhong, A.; Chen, J. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Skin Res Technol 2023, 29, e13229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rischin, D.; Khushalani, N.I.; Schmults, C.D.; Guminski, A.; Chang, A.L.S.; Lewis, K.D.; Lim, A.M.; Hernandez-Aya, L.; Hughes, B.G.M.; Schadendorf, D.; et al. Integrated analysis of a phase 2 study of cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of outcomes and quality of life analysis. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9, e002757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, B.G.M.; Guminski, A.; Bowyer, S.; Migden, M.R.; Schmults, C.D.; Khushalani, N.I.; Chang, A.L.S.; Grob, J.J.; Lewis, K.D.; Ansstas, G.; et al. A phase 2 open-label study of cemiplimab in patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (EMPOWER-CSCC-1): final long-term analysis of groups 1, 2, and 3, and primary analysis of fixed-dose treatment group 6. J Am Acad Dermatol 2025, 92, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maubec, E.; Boubaya, M.; Petrow, P.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Deschamps, L.; Grob, J.J.; Dréno, B.; Scheer-Senyarich, I.; Bloch-Queyrat, C.; et al. Phase II study of pembrolizumab as first-line, single-drug therapy for patients with unresectable cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 3051–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B.G.M.; Munoz-Couselo, E.; Mortier, L.; Bratland, Å.; Gutzmer, R.; Roshdy, O.; González Mendoza, R.; Schachter, J.; Arance, A.; Grange, F.; et al. Pembrolizumab for locally advanced and recurrent/metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-629 study): an open-label, nonrandomized, multicenter, phase II trial. Ann Oncol 2021, 32, 1276–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, A.; Thistlethwaite, F.; De Vries, E.G.E.; Eskens, F.A.L.M.; Uboha, N.; Ott, P.A.; LoRusso, P.; Garcia-Corbacho, J.; Boni, V.; Bendell, J.; et al. CX-072 (pacmilimab), a Probody® PD-L1 inhibitor, in advanced or recurrent solid tumors (PROCLAIM-CX-072): an open-label dose-finding and first-in-human study. J Immunother Cancer 2021, 9, e002447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzmann, M.; Leiter, U.; Loquai, C.; Zimmer, L.; Ugurel, S.; Gutzmer, R.; Thoms, K.M.; Enk, A.H.; Hassel, J.C. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: real-world data of a retrospective, multicenter study. Eur J Cancer 2020, 138, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hober, C.; Fredeau, L.; Pham-Ledard, A.; Boubaya, M.; Herms, F.; Celerier, P.; Aubin, F.; Beneton, N.; Dinulescu, M.; Jannic, A.; et al. Cemiplimab for locally advanced and metastatic cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas: real-life experience from the French CAREPI Study Group. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin, J.; Gérard, E.; Ferte, T.; Prey, S.; Dousset, L.; Dutriaux, C.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Pham-Ledard, A. Real world safety outcomes using cemiplimab for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Geriatr Oncol 2021, 12, 1110–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strippoli, S.; Fanizzi, A.; Quaresmini, D.; Nardone, A.; Armenio, A.; Figliuolo, F.; Filotico, R.; Fucci, L.; Mele, F.; Traversa, M.; et al. Cemiplimab in an elderly frail population of patients with locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a single-center real-life experience from Italy. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 686308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, G.K.; Vaidya, P.; Filkins, A.; Hermel, D.J.; King, K.G.; Ragab, O.; Tseng, W.W.; Swanson, M.; Kokot, N.; Lang, J.E.; et al. PD-1 inhibition therapy for advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis from the University of Southern California. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2021, 147, 1803–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, U.; Loquai, C.; Reinhardt, L.; Rafei-Shamsabadi, D.; Gutzmer, R.; Kaehler, K.; Heinzerling, L.; Hassel, J.C.; Glutsch, V.; Sirokay, J.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition therapy for advanced skin cancer in patients with concomitant hematological malignancy: a retrospective multicenter DeCOG study of 84 patients. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8, e000897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munhoz, R.R.; Nader-Marta, G.; de Camargo, V.P.; Queiroz, M.M.; Cury-Martins, J.; Ricci, H.; de Mattos, M.R.; de Menezes, T.A.F.; Machado, G.U.C.; Bertolli, E.; et al. A phase 2 study of first-line nivolumab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. Cancer 2022, 128, 4223–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, L.S.; Lim, A.M.; Bressel, M.; Lee, J.; Ladwa, R.; Guminski, A.D.; Hughes, B.; Bowyer, S.; Briscoe, K.; Harris, S.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in Australia: a retrospective real world cohort study. Med J Aust 2024, 220, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, L.S.; Lim, A.M.; Bressel, M.; Thai, A.A.; Rischin, D. Real-world experience of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in older patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Drugs Aging 2024, 41, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, E.; Ogata, D.; Namikawa, K.; Yamazaki, N. Real-world efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1 antibody therapy for patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a single-center retrospective study in Japan. J Dermatol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildiers, H.; Heeren, P.; Puts, M.; Topinkova, E.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.G.; Extermann, M.; Falandry, C.; Artz, A.; Brain, E.; Colloca, G.; et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014, 32, 2595–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohile, S.G.; Dale, W.; Somerfield, M.R.; Schonberg, M.A.; Boyd, C.M.; Burhenn, P.S.; Canin, B.; Cohen, H.J.; Holmes, H.M.; Hopkins, J.O.; et al. Practical assessment and management of vulnerabilities in older patients receiving chemotherapy: ASCO guideline for geriatric oncology. J Clin Oncol 2018, 36, 2326–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolly, T.A.; Deal, A.M.; Nyrop, K.A.; Williams, G.R.; Pergolotti, M.; Wood, W.A.; Alston, S.M.; Gordon, B.B.E.; Dixon, S.A.; Moore, S.G.; et al. Geriatric assessment-identified deficits in older cancer patients with normal performance status. Oncologist 2015, 20, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakida, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Uchino, J.; Tabuchi, Y.; Komori, S.; Asai, J.; Arai, A.; Tsunezuka, H.; Kosuga, T.; Konishi, H.; et al. Safety and tolerability of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in elderly and frail patients with advanced malignancies. Oncol Lett 2020, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebhan, C.A.; Cortellini, A.; Ma, W.; Ganta, T.; Song, H.; Ye, F.; Irlmeier, R.; Debnath, N.; Saeed, A.; Radford, M.; et al. Clinical outcomes and toxic effects of single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors among patients aged 80 years or older with cancer: a multicenter international cohort study. JAMA Oncol 2021, 7, 1856–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikoma, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Boku, S.; Motoki, Y.; Kinoshita, H.; Kosaka, H.; Kaibori, M.; Inoue, K.; Sekimoto, M.; Fujisawa, T.; et al. Safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients aged over 80 years: a retrospective cohort study. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2024, 73, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Gill, A.S.; Perez, C.A.; Jain, D. Management of immunotherapy toxicities in older adults. Semin Oncol 2018, 45, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.; Nebhan, C.A.; Johnson, D.B. Impact of patient age on clinical efficacy and toxicity of checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 786046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruijnen, C.P.; Koldenhof, J.J.; Verheijden, R.J.; van den Bos, F.; Emmelot-Vonk, M.H.; Witteveen, P.O.; Suijkerbuijk, K.P.M. Frailty and checkpoint inhibitor toxicity in older patients with melanoma. Cancer 2022, 128, 2746–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grob, J.J.; Gonzalez, R.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Vornicova, O.; Schachter, J.; Joshi, A.; Meyer, N.; Grange, F.; Piulats, J.M.; Bauman, J.R.; et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for recurrent or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a single-arm phase II trial (KEYNOTE-629). J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 2916–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, W.; Wu, N.; Chen, C.I.; Inocencio, T.J.; LaFontaine, P.R.; Seebach, F.; Fury, M.; Harnett, J.; Ruiz, E.S. Real-world treatment patterns and outcomes of cemiplimab in patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma treated in US oncology practices. Cancer Manag Res 2024, 16, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcovich, S.; Colloca, G.; Sollena, P.; Andrea, B.; Balducci, L.; Cho, W.C.; Bernabei, R.; Peris, K. Skin cancer epidemics in the elderly as an emerging issue in geriatric oncology. Aging Dis 2017, 8, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Yoshino, K. Management of elderly patients with advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2022, 52, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembielak, A.; Yau, T.; Akagunduz, B.; Aspeslagh, S.; Colloca, G.; Conway, A.; Danwata, F.; Del Marmol, V.; O’Shea, C.; Verhaert, M.; et al. Recommendations of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology on skin cancer management in older patients. J Geriatr Oncol 2023, 14, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denaro, N.; Passoni, E.; Indini, A.; Nazzaro, G.; Beltramini, G.A.; Benzecry, V.; Colombo, G.; Cauchi, C.; Solinas, C.; Scartozzi, M.; et al. Cemiplimab in ultra-octogenarian patients with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: the real-life experience of a tertiary referral center. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Perez-de-Celis, E.; Li, D.; Yuan, Y.; Lau, Y.M.; Hurria, A. Functional versus chronological age: geriatric assessments to guide decision making in older patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol 2018, 19, e305–e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Fritz, M.; Que, S.K.T. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: an updated review. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, P.; Alberti, A.; Bergamini, C.; Resteghini, C.; Locati, L.D.; Alfieri, S.; Cavalieri, S.; Colombo, E.; Gurizzan, C.; Lorini, L.; et al. Immunotherapy followed by cetuximab in locally advanced/metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas: the I-TACKLE trial. Eur J Cancer 2025, 220, 115379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Sun, J.M.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, J.S.; Park, K.; Ahn, M.J. Are there any ethnic differences in the efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors for treatment of lung cancer? J Thorac Dis 2020, 12, 3796–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565455 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Kuo, L.; Kuwelker, S.; Tsai, E. Management of autoimmune and viral hepatitis in immunotherapy: a narrative review. Ann Palliat Med 2023, 12, 1275–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Wu, Y.L. Immunotherapy in the Asiatic population: any differences from Caucasian population? J Thorac Dis 2018, 10, S1482–S1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geidel, G.; Heidrich, I.; Kött, J.; Schneider, S.W.; Pantel, K.; Gebhardt, C. Emerging precision diagnostics in advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. NPJ Precis Oncol 2022, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, N.D.; Miller, D.M.; Khushalani, N.I.; Divi, V.; Ruiz, E.S.; Lipson, E.J.; Meier, F.; Su, Y.B.; Swiecicki, P.L.; Atlas, J.; et al. Neoadjuvant cemiplimab and surgery for stage II-IV cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: follow-up and survival outcomes of a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2023, 24, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rischin, D.; Porceddu, S.; Day, F.; Brungs, D.P.; Christie, H.; Jackson, J.E.; Stein, B.N.; Su, Y.B.; Ladwa, R.; Adams, G.; et al. Adjuvant cemiplimab or placebo in high-risk cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2025, 393, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Key clinical trials of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in advanced cSCC.

Table 1.

Key clinical trials of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in advanced cSCC.

| Agent/trial |

Phase |

Population |

N |

ORR |

CR |

DOR/survival |

Safety |

Reference |

| Cemiplimab/EMPOWER-CSCC-1 |

I/II |

Locally advanced/metastatic |

85 (pivotal 59, phase 1 expansion 26) (Migden 2018), 115 (Rischin 2021), 108 (Hughes 2025) |

41.1–50% |

5.4–16.9% |

3–4-year OS >70% |

Grade ≥3 TRAEs 13.9% |

Migden et al. 2018 [33]; Rischin et al. 2021 [40]; Hughes et al. 2025 [41] |

| Pembrolizumab/KEYNOTE-629 |

II |

Locally advanced (LA), recurrent/metastatic (R/M) |

159 (LA 54, R/M 105) |

LA 50%, R/M 35.2% |

LA 16.7%, R/M 10.5% |

Median DOR not reached (95% CI, 23.3 months–NR) |

Grade ≥3 TRAEs 11.9% |

Hughes et al. 2021 [43] |

| Pembrolizumab/CARSKIN |

II |

First-line unresectable |

57 (primary, 39; expansion, 18) |

42% (primary, 41%) |

7% (primary, 8%) |

Week 15 DCR 60% (primary, 54%) |

Grade ≥3 11%

Higher response in PD-L1+ tumors, manageable safety |

Maubec et al. 2020 [42] |

| Pacmilimab/PROCLAIM- CX-072 |

I |

Advanced solid tumors, incl. cSCC |

14 (cSCC) |

36% |

7% |

Not reported |

Grade ≥3 TRAEs 15% (all cohort) |

Naing et al. 2021 [44] |

Table 2.

Real-world outcomes of PD-1 inhibitors in advanced cSCC.

Table 2.

Real-world outcomes of PD-1 inhibitors in advanced cSCC.

| Region |

Study/setting |

N |

Median age |

ORR |

OS/PFS |

Key notes |

Reference |

| Europe (Germany) |

Multicenter retrospective, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, or cemiplimab |

46 |

76 |

58.7% (CR, 15.2%) |

1-yr PFS, 58.8% |

DCR 80.4%, <10% discontinued due to toxicity |

Salzmann et al. 2020 [45] |

| Europe (France) |

Multicenter retrospective, cemiplimab |

245 |

77 |

50.4% (CR, 21%) |

1-yr OS, 63.1% |

Grade ≥3 irAEs 9%, 1 fatal TEN |

Hober et al. 2021 [46] |

| Europe (France, older) |

Single-center retrospective, cemiplimab |

22 |

83 |

32% (CR, 9%) |

Not reported |

High discontinuation (41%) due to toxicity |

Valentin et al. 2021 [47] |

| Europe (Italy) |

Single-center retrospective, frail cohort, cemiplimab |

30 |

81 |

76.7% (CR, 30%) |

Median PFS, 16 mo; OS, 18 mo |

83% frail, responses observed in immunocompromised |

Strippoli et al. 2021 [48] |

| United States |

Single institution, retrospective, cemiplimab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab |

26 |

64.5 |

42.3% (CR, 23.1%) |

Median PFS, 5.4 mo |

Higher TMB and head/neck primary associated with response |

In et al. 2021 [49] |

| United States |

Multicenter retrospective, incl. hematological malignancy, anti-PD-1 (cSCC subset) |

15 (cSCC subset) |

Not reported |

26.7% (CR, 6.7%) |

Median PFS, 4.0 mo; OS, 14.9 mo |

Shorter benefit in hematological malignancies |

Leiter et al. 2020 [50] |

| Latin America |

Multicenter retrospective, nivolumab |

24 |

74 |

58.3% |

Median PFS, 12.7 mo; OS, 20.7 mo |

No CRs, feasibility demonstrated |

Munhoz et al. 2022 [51] |

| Australia |

Multicenter retrospective, cemiplimab or pembrolizumab |

286 |

75.2 |

60% (CR, 27%) |

1-yr OS, 78% |

31% immunocompromised; ECOG PS, ≥2.21% |

McLean et al. 2024 [52] |

| Australia |

Single-center retrospective, cemiplimab or pembrolizumab |

53 |

81.8 (range, 70.1–96.8) |

57% (CR, 33%) |

1-yr OS, 63%; PFS, 41% |

34% immunocompromised; ECOG PS, ≥2.34%

Worse OS and PFS in poorer ECOG PS |

McLean et al. 2024 [53] |

| Asia (Japan) |

Single-center retrospective, pembrolizumab or nivolumab |

14 |

64.5 |

57.1% (CR, 14.3%) |

1-year OS, 73.1%; 1-year PFS, 56.2% |

Only one patient (7.1%) with grade 3 AE, no grade 4–5 toxicities |

Nakano et al. 2025 [54] |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).