Submitted:

26 October 2025

Posted:

28 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Nanobodies: Structure and Advantages

3. Mechanisms of Nanobody-Based Immunotherapy in Alzheimer’s Disease

3.1. Amyloid-Beta Aggregates

3.2. Tau Pathology

3.3. Neuroinflammation

3.5. Translational Approaches and Challenges

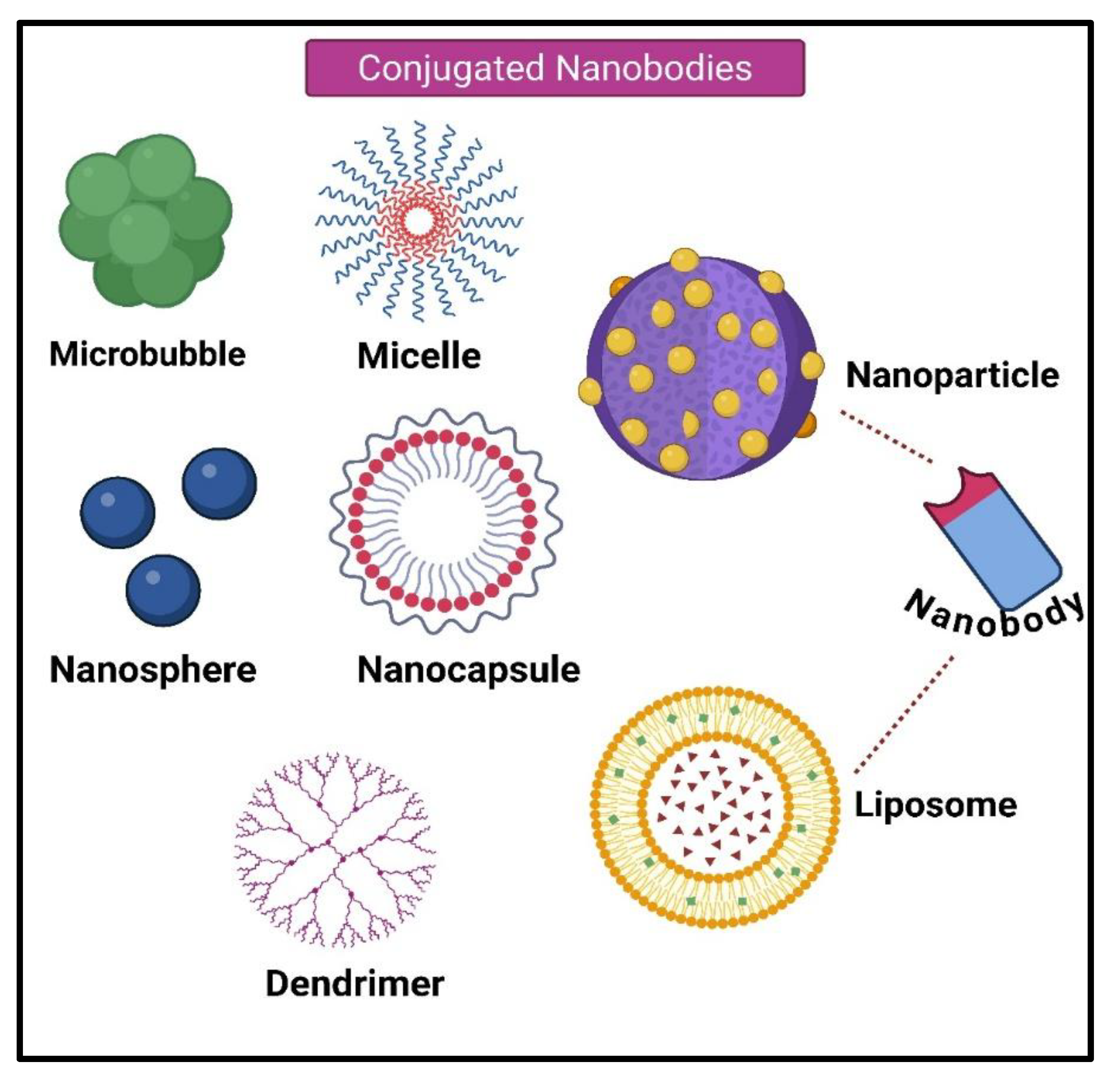

4. Nanobody-Based Drug Delivery Systems

4.1. Direct Injection of Nanobodies

4.2. Nanobodies Conjugated to the Drug and Toxin

4.3. Nanobodies Attached to Nanocarriers

4.4. Nanobody-Based Immunotoxin

4.5. Nanoparticles or Liposomes-Conjugated Nanobodies

4.5.1. Microbubbles

4.5.2. Micelles

4.5.3. Dendrimers

4.5.4. Nanospheres

4.5.5. Nanocapsules

4.6. Albumin Nanoparticles-Conjugated Nanobodies

4.7. Gene Therapy-Associated Nanobody

5. Nanobody Delivery in AD

6. Emerging Nanobody-Based Therapeutic Strategies

6.1. A Revolution in the Treatment of AD

6.1.1. Bispecific Antibody Platform

6.1.2. Trispecific Antibodies

6.1.3. CRISPR-Based Gene Editing:

6.1.4. Advanced Systems of Delivery

6.1.5. Combination Treatments

7. Preclinical and Clinical Progress of Nanobody-Based Therapeutics

7.1. Bispecific Antibodies

7.7.1. Pathology Targeting Bispecific Antibodies

7.7.2. Bispecific BBB-Shuttling Antibodies

7.7.3. BBB Bypass

7.7.4. Alternative Strategies

8. Challenges and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflict of Interest

References

- Safiri, S.; Jolfayi, A.G.; Fazlollahi, A.; Morsali, S.; Sarkesh, A.; Sorkhabi, A.D.; Golabi, B.; Aletaha, R.; Asghari, K.M.; Hamidi, S.; et al. Alzheimer's disease: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, risk factors, symptoms diagnosis, management, caregiving, advanced treatments and associated challenges. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1474043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Zhou, Q.A. Alzheimer’s Disease: Exploring the Landscape of Cognitive Decline. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 3800–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaopeng, Z.; Jing, Y.; Xia, L.; Xingsheng, W.; Juan, D.; Yan, L.; Baoshan, L. Global Burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias in adults aged 65 years and older, 1991–2021: population-based study. Front. Public Heal. 2025, 13, 1585711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannopoulou, K.G.; Papageorgiou, S.G. Current and Future Treatments in Alzheimer Disease: An Update. J. Central Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-M. Recent Advances in Antibody Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease: Focus on Bispecific Antibodies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehlin, D.; Hultqvist, G.; Michno, W.; Aguilar, X.; Dahlén, A.D.; Cerilli, E.; Bucher, N.M.; Broek, S.L.v.D.; Syvänen, S. Bispecific brain-penetrant antibodies for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Prev. Alzheimer's Dis. 2025, 12, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.; Leong, K.W. Discovery of nanobodies: a comprehensive review of their applications and potential over the past five years. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, B.-K.; Odongo, S.; Radwanska, M.; Magez, S. NANOBODIES®: A Review of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.; Gao, Y.; Han, J. Application Progress of the Single Domain Antibody in Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Sapienza, G.; Rossotti, M.A.; Rosa, S.T.-D. Single-Domain Antibodies As Versatile Affinity Reagents for Analytical and Diagnostic Applications. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 977–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Tang, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, X. Nanobody: a promising toolkit for molecular imaging and disease therapy. EJNMMI Res. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovcevska, I.; Muyldermans, S. The Therapeutic Potential of Nanobodies. BioDrugs 2020, 34, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-López, E.; Schuhmacher, A.J. Transportation of Single-Domain Antibodies through the Blood–Brain Barrier. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, L.; Voltà-Durán, E.; Parladé, E.; Mazzega, E.; Sánchez-Chardi, A.; Serna, N.; López-Laguna, H.; Mitstorfer, M.; Unzueta, U.; Vázquez, E.; et al. Self-Assembled Nanobodies as Selectively Targeted, Nanostructured, and Multivalent Materials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 29406–29415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zaro, J.L.; Shen, W.-C. Fusion protein linkers: Property, design and functionality. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Pang, Y.; Li, L.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Raes, G. Applications of nanobodies in brain diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 978513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasturirangan, S.; Li, L.; Emadi, S.; Boddapati, S.; Schulz, P.; Sierks, M.R. Nanobody specific for oligomeric beta-amyloid stabilizes nontoxic form. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolar, M.; Hey, J.; Power, A.; Abushakra, S. Neurotoxic Soluble Amyloid Oligomers Drive Alzheimer’s Pathogenesis and Represent a Clinically Validated Target for Slowing Disease Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jank, L.; Pinto-Espinoza, C.; Duan, Y.; Koch-Nolte, F.; Magnus, T.; Rissiek, B. Current Approaches and Future Perspectives for Nanobodies in Stroke Diagnostic and Therapy. Antibodies 2019, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, J.R.; Whitmore, C.A.; Behof, W.J.; Landman, C.A.; Ong, H.H.; Feld, A.P.; Suero, I.C.; Greer, C.B.; Gore, J.C.; Wijesinghe, P.; et al. Targeting soluble amyloid-beta oligomers with a novel nanobody. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danis, C.; Dupré, E.; Zejneli, O.; Caillierez, R.; Arrial, A.; Bégard, S.; Mortelecque, J.; Eddarkaoui, S.; Loyens, A.; Cantrelle, F.-X.; et al. Inhibition of Tau seeding by targeting Tau nucleation core within neurons with a single domain antibody fragment. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 1484–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizynski, B.; Dzwolak, W.; Nieznanski, K. Amyloidogenesis of Tau protein. Protein Sci. 2017, 26, 2126–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Pilipich, N.; Smerdou, C.; Vanrell, L. A Small Virus to Deliver Small Antibodies: New Targeted Therapies Based on AAV Delivery of Nanobodies. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haqqani, A.S.; Bélanger, K.; Stanimirovic, D.B. Receptor-mediated transcytosis for brain delivery of therapeutics: receptor classes and criteria. Front. Drug Deliv. 2024, 4, 1360302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, G.K.; Caram-Salas, N.; Haqqani, A.S.; Brunette, E.; Eldredge, J.; Pepinsky, B.; Antognetti, G.; Baumann, E.; Ding, W.; Garber, E.; et al. A novel platform for engineering blood-brain barrier-crossing bispecific biologics. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 4764–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porro, G.; Basile, M.; Xie, Z.; Tuveri, G.M.; Battaglia, G.; Lopes, C.D. A new era in brain drug delivery: Integrating multivalency and computational optimisation for blood–brain barrier permeation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2025, 224, 115637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Yuan, J.; Yang, Y.; Yue, Y.; Hu, Z.; Fadera, S.; Chen, H. Incisionless targeted adeno-associated viral vector delivery to the brain by focused ultrasound-mediated intranasal administration. EBioMedicine 2022, 84, 104277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischell, J.M.; Fishman, P.S. A Multifaceted Approach to Optimizing AAV Delivery to the Brain for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-H.; Wei, K.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Wen, C.-J.; Yen, T.-C.; Liu, C.-L.; Lin, Y.-T.; Chen, J.-C.; Shen, C.-R. Noninvasive and Targeted Gene Delivery into the Brain Using Microbubble-Facilitated Focused Ultrasound. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e57682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidian, M.; Ploegh, H. Nanobodies as non-invasive imaging tools. Immuno-Oncology Technol. 2020, 7, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Nabuurs, R.J.; Rutgers, K.S.; Welling, M.M.; Metaxas, A.; E De Backer, M.; Rotman, M.; Bacskai, B.J.; A Van Buchem, M.; Van Der Maarel, S.M.; Van Der Weerd, L. In Vivo Detection of Amyloid-β Deposits Using Heavy Chain Antibody Fragments in a Transgenic Mouse Model for Alzheimer's Disease. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e38284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiba, U.; Descallar, J.; Kreilaus, F.; Adhikari, U.K.; Kumar, S.; Morley, J.W.; Bui, B.V.; Koronyo-Hamaoui, M.; Tayebi, M. Detection of retinal and blood Aβ oligomers with nanobodies. Alzheimer's Dementia: Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2021, 13, e12193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abskharon, R.; Pan, H.; Sawaya, M.R.; Seidler, P.M.; Olivares, E.J.; Chen, Y.; Murray, K.A.; Zhang, J.; Lantz, C.; Bentzel, M.; et al. Structure-based design of nanobodies that inhibit seeding of Alzheimer’s patient–extracted tau fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wei, W.; Lan, X.; Cai, W. Albumin binding improves nanobody pharmacokinetics for dual-modality PET/NIRF imaging of CEACAM5 in colorectal cancer models. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 50, 2591–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kong, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, A.; Ying, T.; Wu, Y. Half-life extension of single-domain antibody–drug conjugates by albumin binding moiety enhances antitumor efficacy. Medcomm 2024, 5, e557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, K.; Xia, X.; Zou, Y.; Shi, B. Small Scale, Big Impact: Nanotechnology-Enhanced Drug Delivery for Brain Diseases. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 3777–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tu, B.; Sun, Y.; Liao, L.; Lu, X.; Liu, E.; Huang, Y. Nanobody-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. J. Control. Release 2025, 381, 113562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLoughlin, C.D.; Nevins, S.; Stein, J.B.; Khakbiz, M.; Lee, K. Overcoming the Blood–Brain Barrier: Multifunctional Nanomaterial-Based Strategies for Targeted Drug Delivery in Neurological Disorders. Small Sci. 2024, 4, 2400232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolvahab, M.H.; Karimi, P.; Mohajeri, N.; Abedini, M.; Zare, H. Targeted drug delivery using nanobodies to deliver effective molecules to breast cancer cells: the most attractive application of nanobodies. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momin, N.; Palmeri, J.R.; Lutz, E.A.; Jailkhani, N.; Mak, H.; Tabet, A.; Chinn, M.M.; Kang, B.H.; Spanoudaki, V.; Hynes, R.O.; et al. Maximizing response to intratumoral immunotherapy in mice by tuning local retention. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Toribio, A.; Muyldermans, S.; Frankel, G.; Fernández, L.Á. Direct Injection of Functional Single-Domain Antibodies from E. coli into Human Cells. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e15227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Lutz, E.; Jailkhani, N.; Momin, N.; Huang, Y.; Sheen, A.; Kang, B.H.; Wittrup, K.D.; O Hynes, R. Intratumoral nanobody–IL-2 fusions that bind the tumor extracellular matrix suppress solid tumor growth in mice. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talelli, M.; Rijcken, C.J.; Oliveira, S.; van der Meel, R.; van Bergen en Henegouwen, P.M.; Lammers, T.; van Nostrum, C.F.; Storm, G.; Hennink, W.E. Nanobody — Shell functionalized thermosensitive core-crosslinked polymeric micelles for active drug targeting. J. Control. Release 2011, 151, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Schiffelers, R.M.; van der Veeken, J.; van der Meel, R.; Vongpromek, R.; van Bergen En Henegouwen, P.M.P.; Storm, G.; Roovers, R.C. Downregulation of EGFR by a novel multivalent nanobody-liposome platform. J. Control. Release 2010, 145, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meel, R.; Oliveira, S.; Altintas, I.; Haselberg, R.; van der Veeken, J.; Roovers, R.C.; Henegouwen, P.M.v.B.E.; Storm, G.; Hennink, W.E.; Schiffelers, R.M.; et al. Tumor-targeted Nanobullets: Anti-EGFR nanobody-liposomes loaded with anti-IGF-1R kinase inhibitor for cancer treatment. J. Control. Release 2012, 159, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijanka, M.; Warnders, F.J.; El Khattabi, M.; Lub-de Hooge, M.; van Dam, G.M.; Ntziachristos, V.; de Vries, L.; Oliveira, S.; van Bergen En Henegouwen, P.M. Rapid optical imaging of human breast tumour xenografts using anti-HER2 VHHs site-directly conjugated to IRDye 800CW for image-guided surgery. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2013, 40, 1718–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhanova, A.; Even-Desrumeaux, K.; Kisserli, A.; Tabary, T.; Reveil, B.; Millot, J.-M.; Chames, P.; Baty, D.; Artemyev, M.; Oleinikov, V.; et al. Oriented conjugates of single-domain antibodies and quantum dots: toward a new generation of ultrasmall diagnostic nanoprobes. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 2012, 8, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massa, S.; Xavier, C.; De Vos, J.; Caveliers, V.; Lahoutte, T.; Muyldermans, S.; Devoogdt, N. Site-Specific Labeling of Cysteine-Tagged Camelid Single-Domain Antibody-Fragments for Use in Molecular Imaging. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014, 25, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakeri, A.; Kouhbanani, M.A.J.; Beheshtkhoo, N.; Beigi, V.; Mousavi, S.M.; Hashemi, S.A.R.; Zade, A.K.; Amani, A.M.; Savardashtaki, A.; Mirzaei, E.; et al. Polyethylenimine-based nanocarriers in co-delivery of drug and gene: a developing horizon. Nano Rev. Exp. 2018, 9, 1488497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.; Kwakkenbos, M.J.; Claassen, Y.B.; Maijoor, K.; Böhne, M.; van der Sluijs, K.F.; Witte, M.D.; van Zoelen, D.J.; Cornelissen, L.A.; Beaumont, T.; et al. Bispecific antibody generated with sortase and click chemistry has broad antiinfluenza virus activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 16820–16825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, C.; Muyldermans, S. Nanobody-Based Delivery Systems for Diagnosis and Targeted Tumor Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1442–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, W.C.; Torchilin, V.; Patri, A.K.; Hrkach, J.; Stern, S.; Lee, R.; Nel, A.; Panaro, N.J.; Grodzinski, P. Best Practices in Cancer Nanotechnology: Perspective from NCI Nanotechnology Alliance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 3229–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-J.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, J.; Hoe, H.-S. EGFR is a potential dual molecular target for cancer and Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1238639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narbona, J.; Hernández-Baraza, L.; Gordo, R.G.; Sanz, L.; Lacadena, J. Nanobody-Based EGFR-Targeting Immunotoxins for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzuto, G.; Molinari, A. Liposomes as nanomedical devices. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 975–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, L.K.; Landfester, K. Natural liposomes and synthetic polymeric structures for biomedical applications. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 468, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debets, M.F.; Leenders, W.P.J.; Verrijp, K.; Zonjee, M.; Meeuwissen, S.A.; Otte-Höller, I.; van Hest, J.C.M. Nanobody-Functionalized Polymersomes for Tumor-Vessel Targeting. Macromol. Biosci. 2013, 13, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godugu, D.; Beedu, S.R. Synthesis, characterisation and anti-tumour activity of biopolymer based platinum nanoparticles and 5-fluorouracil loaded platinum nanoparticles. IET Nanobiotechnology 2018, 13, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neophytou, C.M.; Constantinou, A.I. Drug Delivery Innovations for Enhancing the Anticancer Potential of Vitamin E Isoforms and Their Derivatives. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Taylor, M.; Fullwood, N.; Allsop, D. Liposome delivery systems for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, ume 13, 8507–8522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, P.; Tzouanou, F.; Skolariki, K.; Vamvaka-Iakovou, A.; Noguera-Ortiz, C.; Tsirtsaki, K.; Waites, C.L.; Vlamos, P.; Sousa, N.; Costa-Silva, B.; et al. Extracellular vesicles and Alzheimer’s disease in the novel era of Precision Medicine: implications for disease progression, diagnosis and treatment. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 358, 114183–114183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Wang, L.-R.; Sato, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Berg, M.; Yang, D.-S.; Nixon, R.A.; Liang, X.-J. Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Alleviate Autophagic/Lysosomal Defects in Primary Glia from a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 5110–5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Luo, F.; Zhu, B.; Ling, F.; Wang, E.-L.; Liu, T.-Q.; Wang, G.-X. A Nanobody-Mediated Virus-Targeting Drug Delivery Platform for the Central Nervous System Viral Disease Therapy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0148721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, J.A.; Ansari, J.A.; Ahmed, S.; Khan, A.; Ahemad, N.; Anwar, S. Nano-drug Delivery System: a Promising Approach Against Breast Cancer. Ther. Deliv. 2023, 14, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banihashemi, S.R.; Rahbarizadeh, F.; Hosseini, A.Z.; Ahmadvand, D.; Nikkhoi, S.K. Liposome-based nanocarriers loaded with anthrax lethal factor and armed with anti-CD19 VHH for effectively inhibiting MAPK pathway in B cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 100, 107927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperkar, K.; Patel, D.; Atanase, L.I.; Bahadur, P. Amphiphilic Block Copolymers: Their Structures, and Self-Assembly to Polymeric Micelles and Polymersomes as Drug Delivery Vehicles. Polymers 2022, 14, 4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernot, S.; Unnikrishnan, S.; Du, Z.; Shevchenko, T.; Cosyns, B.; Broisat, A.; Toczek, J.; Caveliers, V.; Muyldermans, S.; Lahoutte, T.; et al. Nanobody-coupled microbubbles as novel molecular tracer. J. Control. Release 2012, 158, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Polymeric micelles drug delivery system in oncology. J. Control. Release 2012, 159, 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G.A. Nanostructure-mediated drug delivery. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 2005, 1, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Bielski, E.R.; Rodrigues, L.S.; Brown, M.R.; Reineke, J.J.; da Rocha, S.R.P. Conjugation to Poly(amidoamine) Dendrimers and Pulmonary Delivery Reduce Cardiac Accumulation and Enhance Antitumor Activity of Doxorubicin in Lung Metastasis. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 2363–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karathanasis, E.; Ghaghada, K.B. Crossing the barrier: treatment of brain tumors using nanochain particles. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnology 2016, 8, 678–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-S.; Harford, J.B.; Pirollo, K.F.; Chang, E.H. Effective treatment of glioblastoma requires crossing the blood–brain barrier and targeting tumors including cancer stem cells: The promise of nanomedicine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 468, 485–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, M.A.; Nayanathara, U.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Such, G.K. Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 5505–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S.T.; Jiang, Y.; Duncan, B.; Kim, C.S.; Saha, K.; Yeh, Y.-C.; Yan, B.; Tang, R.; Hou, S.; et al. Nanoparticle–Dendrimer Hybrid Nanocapsules for Therapeutic Delivery. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, D.S.; Puranik, A.S.; A Peppas, N. Intelligent nanoparticles for advanced drug delivery in cancer treatment. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2015, 7, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.G.; Leuenberger, H.; Kissel, T. Albumin Nanospheres as Carriers for Passive Drug Targeting: An Optimized Manufacturing Technique. Pharm. Res. 1996, 13, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzoghby, A.O.; Samy, W.M.; Elgindy, N.A. Albumin-based nanoparticles as potential controlled release drug delivery systems. J. Control. Release 2012, 157, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altintas, I.; Heukers, R.; van der Meel, R.; Lacombe, M.; Amidi, M.; van Bergen en Henegouwen, P.M.P.; Hennink, W.E.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Kok, R.J. Nanobody-albumin nanoparticles (NANAPs) for the delivery of a multikinase inhibitor 17864 to EGFR overexpressing tumor cells. J. Control. Release 2013, 165, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waehler, R.; Russell, S.J.; Curiel, D.T. Engineering targeted viral vectors for gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frecha, C.; Szecsi, J.; Cosset, F.-L.; Verhoeyen, E. Strategies for Targeting Lentiviral Vectors. Curr. Gene Ther. 2008, 8, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escors, D.; Breckpot, K. Lentiviral Vectors in Gene Therapy: Their Current Status and Future Potential. Arch. Immunol. et Ther. Exp. 2010, 58, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dropulić, B. Lentiviral Vectors: Their Molecular Design, Safety, and Use in Laboratory and Preclinical Research. Hum. Gene Ther. 2011, 22, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyvaerts, C.; De Groeve, K.; Dingemans, J.; Van Lint, S.; Robays, L.; Heirman, C.; Reiser, J.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Thielemans, K.; De Baetselier, P.; et al. Development of the Nanobody display technology to target lentiviral vectors to antigen-presenting cells. Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuki, Y.; Zuo, F.; Kurokawa, S.; Uchida, Y.; Sato, S.; Sakon, N.; Hammarström, L.; Kiyono, H.; Marcotte, H. Lactobacilli as a Vector for Delivery of Nanobodies against Norovirus Infection. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangaiah, D.; Ryan, V.; Van Hoesel, D.; Mane, S.P.; Mckinley, E.T.; Lakshmanan, N.; Reddy, N.D.; Dolk, E.; Kumar, A. Recombinant Limosilactobacillus (Lactobacillus) delivering nanobodies against Clostridium perfringens NetB and alpha toxin confers potential protection from necrotic enteritis. Microbiologyopen 2022, 11, e1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Cao, S.; Lv, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, G.; Tabynov, K.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, E.-M. Nanobody Nb6 fused with porcine IgG Fc as the delivering tag to inhibit porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication in porcine alveolar macrophages. Veter- Res. 2021, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W.S.; Price, S.; Wu, M.; Parmar, M.S. Emerging Gene Therapies for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases: An Overview of Clinical Trials and Promising Candidates. Cureus 2024, 16, e67037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Lu, Z.H.; Shoemaker, C.B.; Tremblay, J.M.; Croix, B.S.; Seaman, S.; Gonzalez-Pastor, R.; Kashentseva, E.A.; Dmitriev, I.P.; Curiel, D.T. Advanced genetic engineering to achieve in vivo targeting of adenovirus utilizing camelid single domain antibody. J. Control. Release 2021, 334, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Zhou, L.; Rincon, M.Y.; Callaerts-Vegh, Z.; Verhaert, J.; Wahis, J.; Creemers, E.; Yshii, L.; Wierda, K.; Saito, T.; et al. AAV-mediated delivery of an anti-BACE1 VHH alleviates pathology in an Alzheimer's disease model. EMBO Mol. Med. 2022, 14, e09824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, K.; Iqbal, U.; Tanha, J.; MacKenzie, R.; Moreno, M.; Stanimirovic, D. Single-Domain Antibodies as Therapeutic and Imaging Agents for the Treatment of CNS Diseases. Antibodies 2019, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Meng, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, M.; Chu, F.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Luo, L. Multivalent Nanobody Conjugate with Rigid, Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging Scaffold for Multi-Target Therapy of Alzheimer's Disease. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2210879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; Shin, M.; Ottoy, J.; Aliaga, A.A.; Mathotaarachchi, S.; Quispialaya, K.; A Pascoal, T.; Collins, D.L.; Chakravarty, M.M.; Mathieu, A.; et al. Preclinical in vivo longitudinal assessment of KG207-M as a disease-modifying Alzheimer’s disease therapeutic. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2021, 42, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, G.; Vincke, C.; Lunding, M.; Jensen, A.M.G.; Madsen, P.; Muyldermans, S.; Kjolby, M.; Andersen, O.M. Epitope mapping of nanobodies binding the Alzheimer’s disease receptor SORLA. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 375, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouters, Y.; Jaspers, T.; De Strooper, B.; Dewilde, M. Identification and in vivo characterization of a brain-penetrating nanobody. Fluids Barriers CNS 2020, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, S.; Berksöz, M.; Zahedimaram, P.; Piepoli, S.; Erman, B. Nanobodies as molecular imaging probes. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 182, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Beer, M.A.; Giepmans, B.N.G. Nanobody-Based Probes for Subcellular Protein Identification and Visualization. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Duan, M.; Pei, D.; Lin, J.; Wang, L.; Zhou, P.; Yao, W.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Tao, L.; et al. Development of novel-nanobody-based lateral-flow immunochromatographic strip test for rapid detection of recombinant human interferon α2b. J. Pharm. Anal. 2021, 12, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, P.M.; Walsh, L.R.; Villa, C.H.; Marcos-Contreras, O.A.; Hood, E.D.; Muzykantov, V.R.; Greineder, C.F. Molecularly Engineered Nanobodies for Tunable Pharmacokinetics and Drug Delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 2020, 31, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- F. Ji, J. Ren, C. Vincke, L. Jia, and S. Muyldermans, "Nanobodies: From Serendipitous Discovery of Heavy Chain-Only Antibodies in Camelids to a Wide Range of Useful Applications," Methods Mol Biol, vol. 2446, pp. 3-17, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Leopold, A.V.; Shcherbakova, D.M.; Verkhusha, V.V. Fluorescent Biosensors for Neurotransmission and Neuromodulation: Engineering and Applications. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, U.; Kontermann, R.E. The making of bispecific antibodies. mAbs 2016, 9, 182–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiess, C.; Zhai, Q.; Carter, P.J. Alternative molecular formats and therapeutic applications for bispecific antibodies. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 67, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, S.K.; Mariam, Z.; Magoola, M. Engineered Antibodies to Improve Efficacy against Neurodegenerative Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, N.M.; Eid, M.A.F.M.; Raj, N.; Kantas, T.M.; Billing, H.S.M.; Sadhu, D.M. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 in the management of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: a review. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 86, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.; Klaus, S.P. Focused ultrasound therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: exploring the potential for targeted amyloid disaggregation. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1426075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariolis, M.S.; Wells, R.C.; Getz, J.A.; Kwan, W.; Mahon, C.S.; Tong, R.; Kim, D.J.; Srivastava, A.; Bedard, C.; Henne, K.R.; et al. Brain delivery of therapeutic proteins using an Fc fragment blood-brain barrier transport vehicle in mice and monkeys. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaay1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Y.; Kim, Y.; Chen, K.; Liang, S.; Mohanty, V.; Iqbal, R. Applied machine learning in Alzheimer's disease research: omics, imaging, and clinical data. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2021, 5, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pornnoppadol, G.; Bond, L.G.; Lucas, M.J.; Zupancic, J.M.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Zhang, B.; Greineder, C.F.; Tessier, P.M. Bispecific antibody shuttles targeting CD98hc mediate efficient and long-lived brain delivery of IgGs. Cell Chem. Biol. 2023, 31, 361–372.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, K.S.; Wells, R.C.; Moshkforoush, A.; Chan, D.; Lechtenberg, K.J.; Tran, H.L.; Chow, J.; Kim, D.J.; Robles-Colmenares, Y.; Srivastava, D.B.; et al. CD98hc is a target for brain delivery of biotherapeutics. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, X.; Huang, L.; Yang, Y.; He, J. Enhancing precision medicine: Bispecific antibody-mediated targeted delivery of lipid nanoparticles for potential cancer therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 654, 123990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, C. Nanobody approval gives domain antibodies a boost. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, M.; Cataland, S.R.; Peyvandi, F.; Coppo, P.; Knöbl, P.; Kremer Hovinga, J.A.; Metjian, A.; De La Rubia, J.; Pavenski, K.; Callewaert, F.; et al. Caplacizumab Treatment for Acquired Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. FDA approves second BCMA-targeted CAR-T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 249–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keam, S.J. Ozoralizumab: First Approval. Drugs 2022, 83, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. M. Awad et al., "Emerging applications of nanobodies in cancer therapy," Int Rev Cell Mol Biol, vol. 369, pp. 143-199, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wouters, Y.; Jaspers, T.; Rué, L.; Serneels, L.; De Strooper, B.; Dewilde, M. VHHs as tools for therapeutic protein delivery to the central nervous system. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, L.; Fan, X.; Li, L.; Li, X.; Arase, H.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, W.; Zheng, H.; et al. A tetravalent TREM2 agonistic antibody reduced amyloid pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabq0095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Collij, L.E.; Stomrud, E.; Binette, A.P.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Smith, R.; Karlsson, L.; Lantero-Rodriguez, J.; Snellman, A.; Strandberg, O.; et al. Plasma Biomarker Strategy for Selecting Patients With Alzheimer Disease for Antiamyloid Immunotherapies. JAMA Neurol. 2024, 81, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tönnies, E.; Trushina, E. Oxidative Stress, Synaptic Dysfunction, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 57, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinchuk, A.; Huynh, T.V.; Shi, Y.; Jackson, R.J.; Finn, M.B.; Manis, M.; Francis, C.M.; Tran, A.C.; Sullivan, P.M.; Ulrich, J.D.; et al. Apolipoprotein E4 Reduction with Antisense Oligonucleotides Decreases Neurodegeneration in a Tauopathy Model. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 89, 952–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, G.; White, C.C.; A Winn, P.; Cimpean, M.; Replogle, J.M.; Glick, L.R.; E Cuerdon, N.; Ryan, K.J.; A Johnson, K.; A Schneider, J.; et al. CD33 modulates TREM2: convergence of Alzheimer loci. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1556–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Osswald, H.L. BACE1 (β-secretase) inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6765–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, M.; Tachibana, M.; Kanekiyo, T.; Bu, G. Role of LRP1 in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: evidence from clinical and preclinical studies. J. Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayas, C.L.; Ávila, J. GSK-3 and Tau: A Key Duet in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2021, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Kummer, M.P.; Stutz, A.; Delekate, A.; Schwartz, S.; Vieira-Saecker, A.; Griep, A.; Axt, D.; Remus, A.; Tzeng, T.-C.; et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 2013, 493, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, S.; Caccamo, A.; Shepherd, J.D.; Murphy, M.P.; Golde, T.E.; Kayed, R.; Metherate, R.; Mattson, M.P.; Akbari, Y.; LaFerla, F.M. Triple-Transgenic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease with Plaques and Tangles: Intracellular Abeta and Synaptic Dysfunction. Neuron 2003, 39, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, J.W.; Bemiller, S.M.; Murtishaw, A.S.; Leisgang, A.M.; Salazar, A.M.; Lamb, B.T. Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dementia: Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018, 4, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Song, W. NLRP3 inflammasome as a novel therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.E.; Phillips, N.A.; Feldman, H.H.; Borrie, M.; Ganesh, A.; Henri-Bhargava, A.; Desmarais, P.; Frank, A.; Badhwar, A.; Barlow, L.; et al. Use of lecanemab and donanemab in the Canadian healthcare system: Evidence, challenges, and areas for future research. J. Prev. Alzheimer's Dis. 2025, 12, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phase II Study of AL002 in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

- Post-Marketing Study of Aducanumab. 2020. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

- Palmqvist, S.; Janelidze, S.; Quiroz, Y.T.; Zetterberg, H.; Lopera, F.; Stomrud, E.; Su, Y.; Chen, Y.; Serrano, G.E.; Leuzy, A.; et al. Discriminative Accuracy of Plasma Phospho-tau217 for Alzheimer Disease vs Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. JAMA 2020, 324, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Shin, K.Y.; Chang, K.-A. GFAP as a Potential Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cells 2023, 12, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardridge, W.M. Delivery of Biologics Across the Blood–Brain Barrier with Molecular Trojan Horse Technology. BioDrugs 2017, 31, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrijn, A.F.; Janmaat, M.L.; Reichert, J.M.; Parren, P.W.H.I. Bispecific antibodies: a mechanistic review of the pipeline. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultqvist, G.; Syvänen, S.; Fang, X.T.; Lannfelt, L.; Sehlin, D. Bivalent Brain Shuttle Increases Antibody Uptake by Monovalent Binding to the Transferrin Receptor. Theranostics 2017, 7, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Han, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y. The blood–brain barrier: Structure, regulation and drug delivery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cao, K.; Xie, J.; Liang, X.; Gong, H.; Luo, Q.; Luo, H. Aβ42 and ROS dual-targeted multifunctional nanocomposite for combination therapy of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardridge, W.M. Receptor-mediated drug delivery of bispecific therapeutic antibodies through the blood-brain barrier. Front. Drug Deliv. 2023, 3, 1227816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).