Submitted:

23 October 2025

Posted:

24 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Overview of the Reward and Reinforcement Circuit

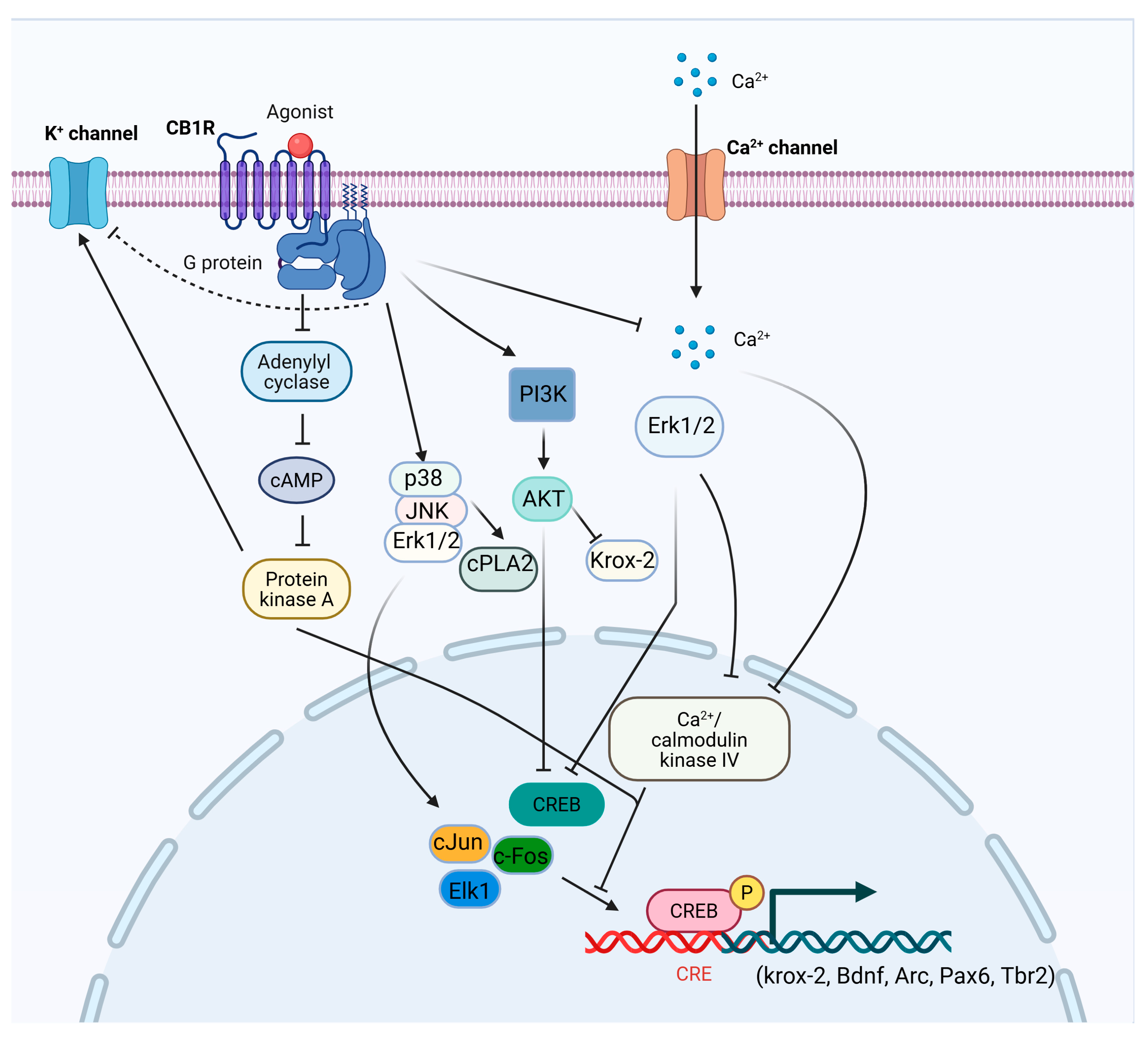

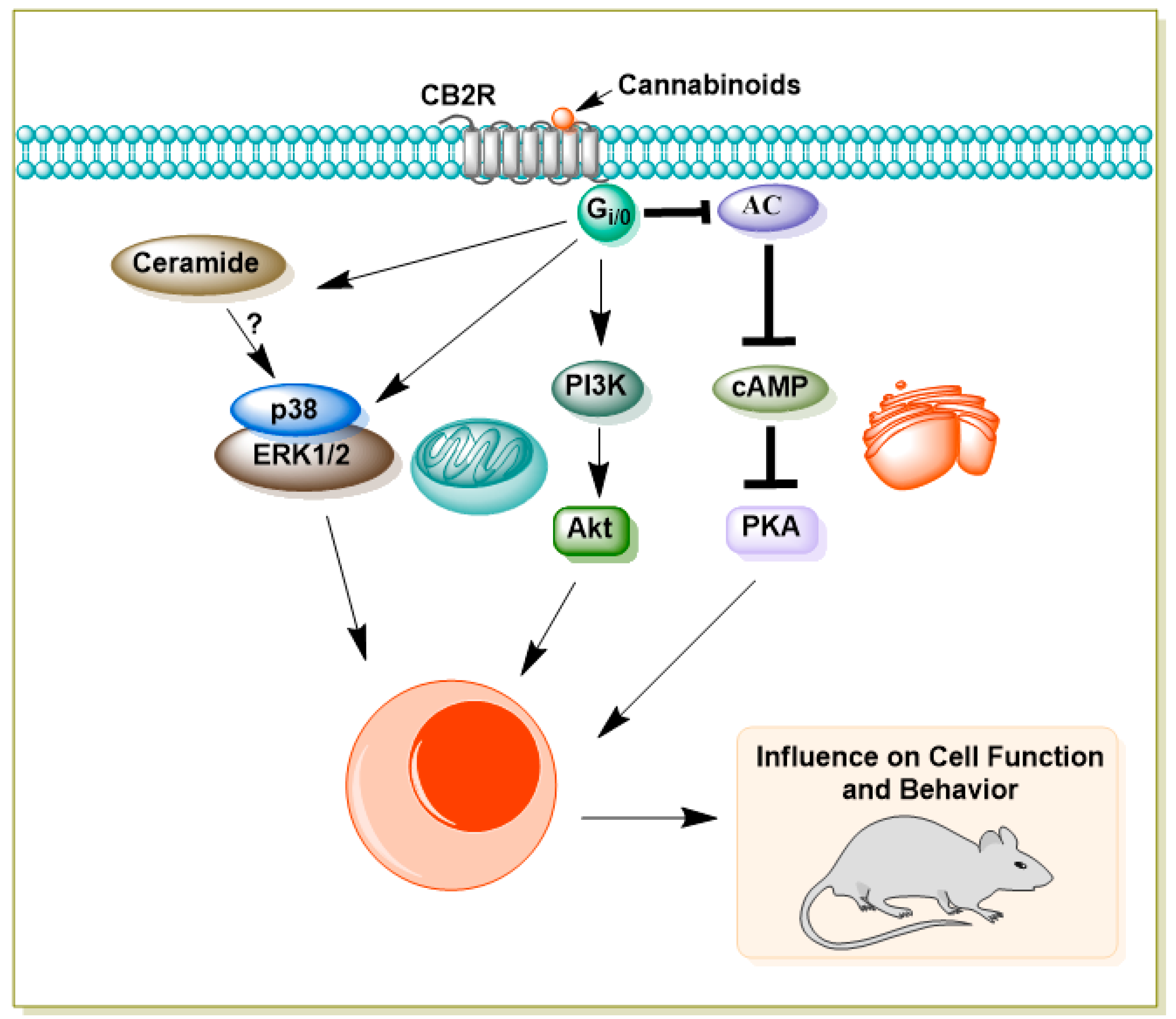

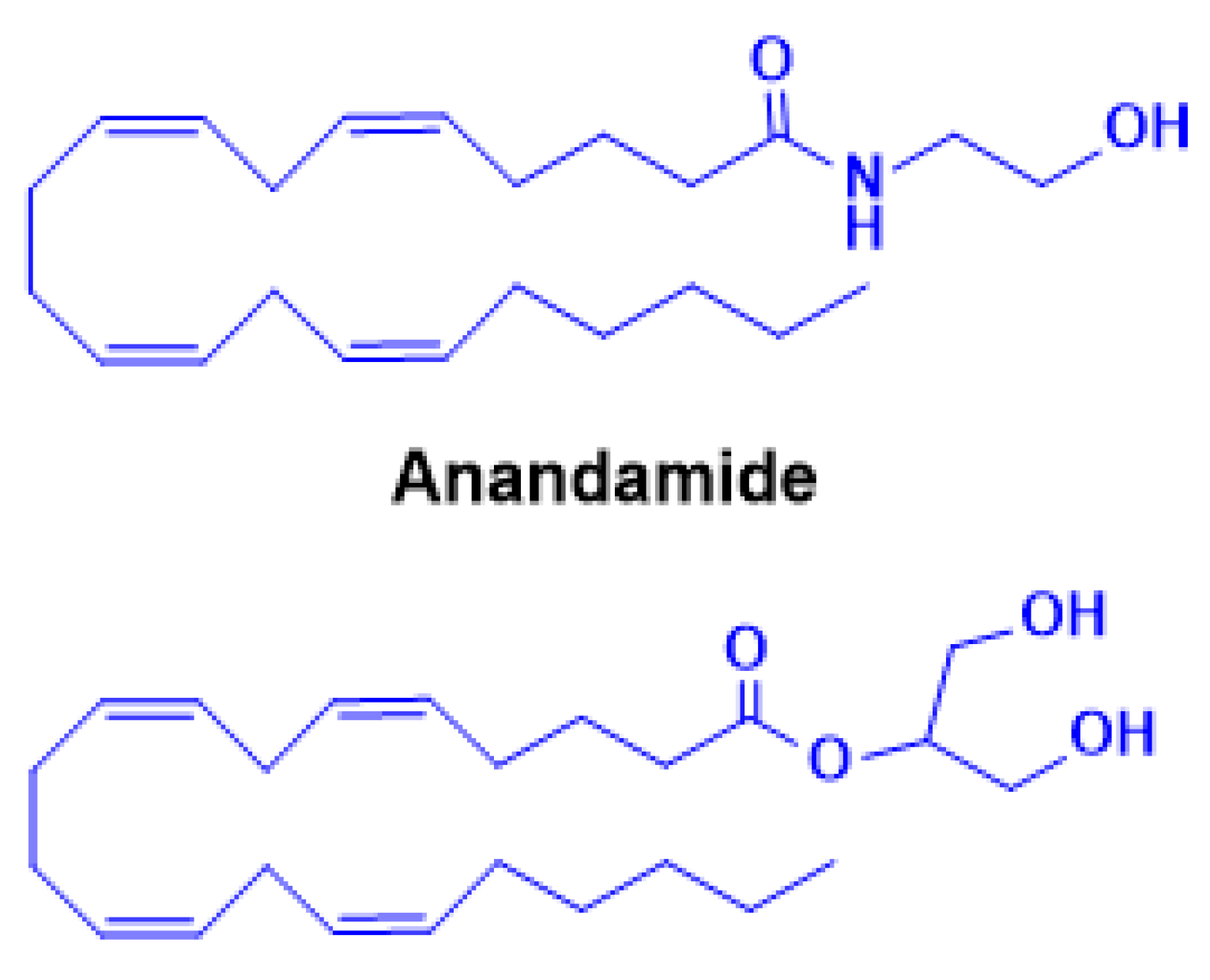

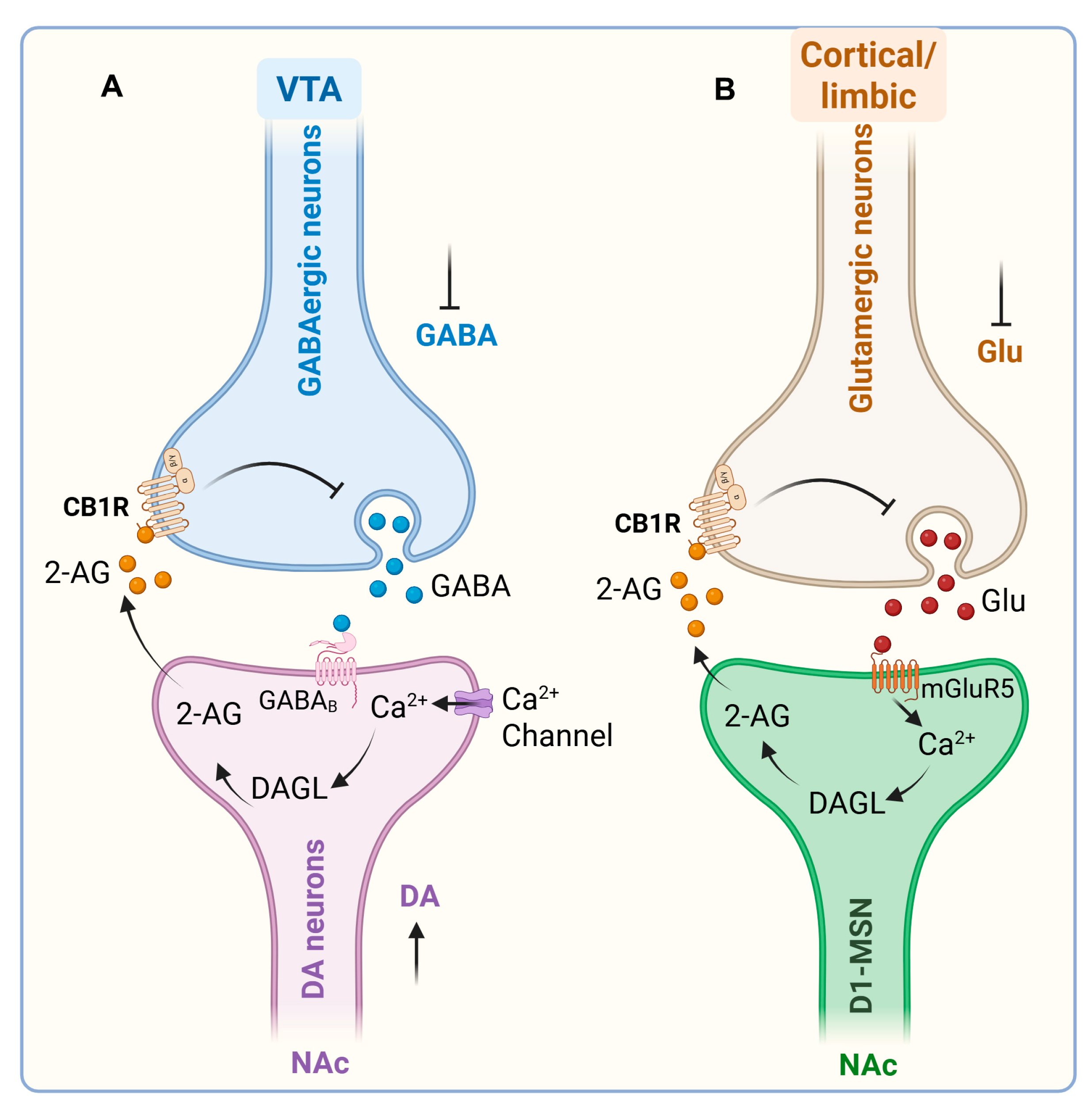

eCB Influence on Dopamine Transmission

3. Drugs of Abuse and Alcohol-induced eCBS Contribution to Neurodegenerative Disorders

3.1. Alcohol Abuse–Induced eCBS Alterations and Neurodegeneration

3.2. Drugs of Abuse–Induced eCBS Alterations and Neurodegeneration

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| eCBS | endocannabinoid system |

| ND | neurodegenerative |

| CB1 | cannabinoid receptors 1 |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| CB2 | cannabinoid receptors 2 |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| Δ9-THC | Δ9- tetrahydrocannabinol |

| GPCR | G protein–coupled receptor |

| PFC | prefrontal cortex |

| NAc | nucleus accumbens |

| cAMP | cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| MAPKs | mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| JNK | Jun N-terminal kinase |

| CREB | cAMP-response element binding protein |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| AKT | protein kinase B |

| Src | family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases |

| VTA | ventral tegmental area |

| VGCC | voltage-gated calcium channels |

| GIRKs | G protein–coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels |

| AEA | N-arachidonoylethanolamine |

| 2-AG | 2-arachidonoylglycerol |

| NAPE | N-acyl-phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PLD | phospholipase D |

| DAG | diacylglycerol |

| DAGLα/β | diacylglycerol alpha/ beta |

| FAAH | fatty acid amide hydrolase |

| MAGL | monoacylglycerol lipase |

| COX-2 | cyclooxygenase-2 |

| DA | Dopamine |

| SR141716A | rimonabant |

| GABA | Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid |

| IPSCs | inhibitory postsynaptic currents |

| MSNs | medium spiny neurons |

| mGluR5 | metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 |

| LTD | long-term depression |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| HD | Huntington’s disease |

| Aβ | β-amyloid |

| AUD | alcohol use disorder |

| ALS | amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| APP/ PSEN | Amyloid protein precursor/presenilin |

| DAT | dopamine transporter |

| MA | methamphetamine |

| SOD1 | superoxide dismutase 1 |

| CNR1 | cannabinoid receptor 1 protein coding gene |

| PPARα | proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| PPARγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

References

- Di Marzo, V. , et al., Endocannabinoids:endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligands with neuromodulatory action. Trends Neurosci 1998, 21, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechoulam, R. Fride, and V. Di Marzo, Endocannabinoids. Eur J Pharmacol 1998, 359, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devane, W.A. , et al., Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol. Pharmacol., 1988, 34, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, A.C. , et al., The cannabinoid receptor: biochemical, anatomical and behavioral characterization. Trends Neurosci 1990, 13, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devane, W.A. , et al., Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science., 1992, 258, 1946–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, L.A. , et al., Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature, 1990, 346, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, L.A., T. I. Bonner, and S.J. Lolait, Localization of cannabinoid receptor mRNA in rat brain. J Comp Neurol, 1993, 327, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compton, D.R. , et al., Cannabinoid structure-activity relationships: correlation of receptor binding and in vivo activities. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1993, 265, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, M. L. Faull, and M.Dragunow, Loss of cannabinoid receptors in the substantia nigra in Huntington's disease. Neuroscience 1993, 56, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, L.S. , et al., Structure-activity relationships for cannabinoid receptor-binding and analgesic activity: studies of bicyclic cannabinoid analogs. Mol Pharmacol 1993, 44, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.R. G.Pertwee, and S.N. Davies, The action of synthetic cannabinoids on the induction of long-term potentiation in the rat hippocampal slice. Eur J Pharmacol 1994, 259, R7–R8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M. , et al., Motor behavior and nigrostriatal dopaminergic activity in adult rats perinatally exposed to cannabinoids. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 1994, 47, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtman, A.H. R.Dimen, and B.R. Martin, Systemic or intrahippocampal cannabinoid administration impairs spatial memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 1995, 119, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, S., K. L. Thomas, and M. Abu-Shaar, Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature, 1993, 365, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breivogel, C.S. and S.R. Childers, Cannabinoid agonist signal transduction in rat brain: comparison of cannabinoid agonists in receptor binding, G-protein activation, and adenylyl cyclase inhibition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2000, 295, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derkinderen, P. , et al., Regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase by cannabinoids in hippocampus. J Neurosci, 2003, 23, 2371–2382. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie, K. , Mechanisms of CB1 receptor signaling: endocannabinoid modulation of synaptic strength. Int J Obes (Lond) 2006, 30 (Suppl 1), S19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechoulam, R. and L.A. Parker, The endocannabinoid system and the brain. Annu Rev Psychol, 2013, 64, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, A.C. , Pharmacology of cannabinoid receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 1995, 35, 607–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, S.R., T. Sexton, and M.B. Roy, Effects of anandamide on cannabinoid receptors in rat brain membranes. Biochem. Pharmacol., 1994, 47, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.C. , et al., Cannabinoid receptor binding and agonist activity of amides and esters of arachidonic acid. Mol. Pharmacol., 1994, 46, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, A.C. and S. Mukhopadhyay, Cellular signal transduction by anandamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol. Chem Phys Lipids., 2000, 108, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, M.P. and D.A. Brown, Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit Ca current in NG108-15 neuroblastoma cells via a pertussis toxin-sensitive mechanism. Br J Pharmacol, 1992, 106, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, K. and B. Hille, Cannabinoids inhibit N-type calcium channels in neuroblastoma-glioma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1992, 89, 3825–3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueron, M.I. , et al., Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit depolarization-induced calcium influx in cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurochem, 2001, 79, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X., S. R. Ikeda, and D.L. Lewis, Rat brain cannabinoid receptor modulates N-type Ca2+ channels in a neuronal expression system. Mol Pharmacol., 1996, 49, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, J. , et al., Cannabinoid receptors differentially modulate potassium A and D currents in hippocampal neurons in culture. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 1999, 291, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, T.F., I. Katona, and D. Piomelli, Role of endogenous cannabinoids in synaptic signaling. Physiol Rev., 2003, 83, 1017–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, A.C. , et al., International Union of Pharmacology. XXVII. Classification of cannabinoid receptors. Pharmacol Rev, 2002, 54, 161–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.S. , et al., Induction of Krox-24 by endogenous cannabinoid type 1 receptors in Neuro2A cells is mediated by the MEK-ERK MAPK pathway and is suppressed by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 29085–29095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, B.S. and O. Arancio, Synaptic Plasticity: Emerging Role for Endocannabinoid system, in Synaptic Plasticity: New Research, T.F. Kaiser and F.J. Peters, Editors. 2008, Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: NY, USA. p. pp77-112.

- Ozaita, A. Puighermanal, and R.Maldonado, Regulation of PI3K/Akt/GSK-3 pathway by cannabinoids in the brain. J Neurochem 2007, 102, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basavarajappa, B.S. , Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Potential Role of Endocannabinoids Signaling. Brain Sci, 2015, 5, 456–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, B.S. and S.Subbanna, CB1 Receptor-Mediated Signaling Underlies the Hippocampal Synaptic, Learning and Memory Deficits Following Treatment with JWH-081, a New Component of Spice/K2 Preparations. Hippocampus 2014, 24, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayewitch, M. , et al., The peripheral cannabinoid receptor: adenylate cyclase inhibition and G protein coupling. FEBS Lett 1995, 375, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egertova, M. , et al., A new perspective on cannabinoid signalling: complementary localization of fatty acid amide hydrolase and the CB1 receptor in rat brain. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 1998, 265, 2081–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, K. , et al., Immunohistochemical distribution of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience, 1998, 83, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsicano, G. and B.Lutz, Expression of the cannabinoid receptor CB1 in distinct neuronal subpopulations in the adult mouse forebrain. Eur J Neurosci 1999, 11, 4213–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzian, A.L. Micale, and C.T. Wotjak, Cannabinoid receptor type 1 receptors on GABAergic vs. glutamatergic neurons differentially gate sex-dependent social interest in mice. Eur J Neurosci 2014, 40, 2293–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haring, M. , et al., Identification of the cannabinoid receptor type 1 in serotonergic cells of raphe nuclei in mice. Neuroscience 2007, 146, 1212–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oropeza, V.C. Mackie, and E.J. Van Bockstaele, Cannabinoid receptors are localized to noradrenergic axon terminals in the rat frontal cortex. Brain Res 2007, 1127, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackie, K. , Cannabinoid receptor homo- and heterodimerization. Life Sci, 2005, 77, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, M. Diez, and A.Araque, Astrocytes in endocannabinoid signalling. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2014, 369, 20130599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota, D. , et al., The endogenous cannabinoid system affects energy balance via central orexigenic drive and peripheral lipogenesis. J Clin Invest, 2003, 112, 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Parolaro, D. , Presence and functional regulation of cannabinoid receptors in immune cells. Life Sci, 1999, 65, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouaboula, M. , et al., Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by stimulation of the central cannabinoid receptor CB1. Biochem J 1995, 312 Pt 2, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuddihey, H. K.MacNaughton, and K.A. Sharkey, Role of the Endocannabinoid System in the Regulation of Intestinal Homeostasis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022, 14, 947–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, A.C. and M.E. Abood, CB(1) and CB(2) Receptor Pharmacology. Adv Pharmacol, 2017, 80, 169–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rezq, S. Hassan, and M.F. Mahmoud, Rimonabant ameliorates hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats: Involvement of autophagy via modulating ERK- and PI3K/AKT-mTOR pathways. Int Immunopharmacol, 2021, 100, 108140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rorabaugh, B.R. and D.J. Morgan, CB1 receptor coupling to extracellular regulated kinase via multiple Galphai/o isoforms. Neuroreport, 2025, 36, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherma, M. , et al., Brain activity of anandamide: a rewarding bliss? Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2019, 40, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L. , et al., The CB1 cannabinoid receptor agonist reduces L-DOPA-induced motor fluctuation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Drug Des Devel Ther, 2014, 8, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Subbanna, S. , et al., Ethanol exposure induces neonatal neurodegeneration by enhancing CB1R Exon1 histone H4K8 acetylation and up-regulating CB1R function causing neurobehavioral abnormalities in adult mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol, 2015, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbanna, S. , et al., Anandamide-CB1 Receptor Signaling Contributes to Postnatal Ethanol-Induced Neonatal Neurodegeneration, Adult Synaptic and Memory Deficits. Journal of neuoscience, 2013, 33, 6350–6366. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, D. , et al., The endocannabinoid anandamide inhibits neuronal progenitor cell differentiation through attenuation of the Rap1/B-Raf/ERK pathway. J Biol Chem, 2002, 277, 46645–46650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez del Pulgar, T., G. Velasco, and M. Guzman, The CB1 cannabinoid receptor is coupled to the activation of protein kinase B/Akt. Biochem J., 2000, 347, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Scala, C. , et al., Anandamide Revisited: How Cholesterol and Ceramides Control Receptor-Dependent and Receptor-Independent Signal Transmission Pathways of a Lipid Neurotransmitter. Biomolecules, 2018, 8.

- Diana, M.A. and A.Marty, Endocannabinoid-mediated short-term synaptic plasticity: depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI) and depolarization-induced suppression of excitation (DSE). Br J Pharmacol, 2004, 142, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waard, M. , et al., Direct binding of G-protein betagamma complex to voltage-dependent calcium channels. Nature 1997, 385, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waard, M. , et al., How do G proteins directly control neuronal Ca2+ channel function? Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2005, 26, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M. Y.Sung, and T.E. Hebert, Gbetagamma subunits-Different spaces, different faces. Pharmacol Res, 2016, 111, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouaboula, M. , et al., Signaling pathway associated with stimulation of CB2 peripheral cannabinoid receptor. Involvement of both mitogen-activated protein kinase and induction of Krox-24 expression. Eur J Biochem, 1996, 237, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maresz, K. , et al., Modulation of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in microglial cells in response to inflammatory stimuli. J Neurochem, 2005, 95, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.P. , et al., Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: immunohistochemical localization in rat brain. Brain Res, 2006, 1071, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onaivi, E.S. , et al., Discovery of the presence and functional expression of cannabinoid CB2 receptors in brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2006, 1074, 514–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Q. , et al., The impact of cannabinoid type 2 receptors (CB2Rs) in neuroprotection against neurological disorders. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2020, 41, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Jia, and Y.Dong, Research progress on the cannabinoid type-2 receptor and Parkinson's disease. Front Aging Neurosci, 2023, 15, 1298166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. and J.Kim, Neuronal expression of CB2 cannabinoid receptor mRNAs in the mouse hippocampus. Neuroscience 2015, 311, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempel, A.V. , et al., Cannabinoid Type 2 Receptors Mediate a Cell Type-Specific Plasticity in the Hippocampus. Neuron, 2016, 90, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.Y. , et al., Expression of functional cannabinoid CB(2) receptor in VTA dopamine neurons in rats. Addict Biol, 2017, 22, 752–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slipetz, D.M. , et al., Activation of the human peripheral cannabinoid receptor results in inhibition of adenylyl cyclase. Mol Pharmacol, 1995, 48, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, J.L. , et al., Agonist-directed trafficking of response by endocannabinoids acting at CB2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2005, 315, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felder, C.C. , et al., Comparison of the pharmacology and signal transduction of the human cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Mol Pharmacol, 1995, 48, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y. , et al., Activation by 2-arachidonoylglycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand, of p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase in HL-60 cells. J Biochem 2001, 129, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Holgado, E. , et al., Cannabinoids promote oligodendrocyte progenitor survival: involvement of cannabinoid receptors and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt signaling. J Neurosci, 2002, 22, 9742–9753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M. , et al., Delineating the interactions between the cannabinoid CB(2) receptor and its regulatory effectors; beta-arrestins and GPCR kinases. Br J Pharmacol, 2022, 179, 2223–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Pastor, A. , et al., Multiple intramolecular triggers converge to preferential G protein coupling in the CB(2)R. Nat Commun, 2025, 16, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, S.D. , et al., Cannabinoid receptors can activate and inhibit G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels in a xenopus oocyte expression system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 1999, 291, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.Y. , et al., Coupling of the expressed cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors to phospholipase C and G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels. Recept Channels, 1999, 6, 363–374. [Google Scholar]

- Soobben, M. Sayed, and I.Achilonu, Exploring the evolutionary trajectory and functional landscape of cannabinoid receptors: A comprehensive bioinformatic analysis. Comput Biol Chem, 2024, 112, 108138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, K. Porel, and K.R. Aran, Emerging roles of cannabinoid receptor CB2 receptor in the central nervous system: therapeutic target for CNS disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 2024, 241, 1939–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertwee, R.G. , Pharmacology of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Pharmacol Ther., 1997, 74, 129–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, N.E. , et al., Expression of the CB1 and CB2 receptor messenger RNAs during embryonic development in the rat. Neuroscience, 1998, 82, 1131–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carracedo, A. , et al., Cannabinoids induce apoptosis of pancreatic tumor cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress-related genes. Cancer Res, 2006, 66, 6748–6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carracedo, A. , et al., The stress-regulated protein p8 mediates cannabinoid-induced apoptosis of tumor cells. Cancer Cell 2006, 9, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, E.J. , et al., Cultured rat microglial cells synthesize the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonylglycerol, which increases proliferation via a CB2 receptor-dependent mechanism. Mol Pharmacol, 2004, 65, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.Y. , et al., Activation of cannabinoid CB2 receptor-mediated AMPK/CREB pathway reduces cerebral ischemic injury. Am J Pathol, 2013, 182, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertsch, J. , et al., Echinacea alkylamides modulate TNF-alpha gene expression via cannabinoid receptor CB2 and multiple signal transduction pathways. FEBS Lett, 2004, 577, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, B. , et al., p38 MAPK is involved in CB2 receptor-induced apoptosis of human leukaemia cells. FEBS Lett, 2005, 579, 5084–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazuelos, J. , et al., Non-psychoactive CB2 cannabinoid agonists stimulate neural progenitor proliferation. FASEB J, 2006, 20, 2405–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, M.T. , et al., Differential roles of CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors in mast cells. J Immunol, 2003, 170, 4953–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechoulam, R. , et al., Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 1995, 50, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, T. , et al., 2-Arachidonoylglycerol: a possible endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligand in brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1995, 215, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marzo, V. and L. De Petrocellis, Why do cannabinoid receptors have more than one endogenous ligand? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2012, 367, 3216–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G. , et al., International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB(1) and CB(2). Pharmacol Rev, 2010, 62, 588–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, S.F. and F.S. Guimaraes, Differential role of CB1 and TRPV1 receptors on anandamide modulation of defensive responses induced by nitric oxide in the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Sullivan, S.E. , An update on PPAR activation by cannabinoids. Br J Pharmacol, 2016, 173, 1899–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, M. , et al., Endocannabinoid-mediated control of synaptic transmission. Physiol Rev, 2009, 89, 309–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katona, I. , et al., Presynaptically located CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate GABA release from axon terminals of specific hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci, 1999, 19, 4544–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alger, B.E. , Retrograde signaling in the regulation of synaptic transmission: focus on endocannabinoids. Progress in Neurobiology., 2002, 68, 247–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, B. , et al., The endocannabinoid system in guarding against fear, anxiety and stress. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2015, 16, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, J. , et al., A biosynthetic pathway for anandamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2006, 103, 13345–13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murataeva, N. Straiker, and K.Mackie, Parsing the players: 2-arachidonoylglycerol synthesis and degradation in the CNS. Br J Pharmacol 2014, 171, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, B.S. , Critical Enzymes Involved in Endocannabinoid Metabolism. Protein and Peptide letters, 2007, 14, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basavarajappa, B.S. , Major Enzymes of Endocannabinoid Metabolism, in Frontiers in Protein and Peptide Sciences, B. Dunn, Editor. 2014, Bentham Science Publishers: Oak Park, IL, USA. p. 31-62.

- Rouzer, C.A. and L.J.Marnett, Endocannabinoid oxygenation by cyclooxygenases, lipoxygenases, and cytochromes P450: cross-talk between the eicosanoid and endocannabinoid signaling pathways. Chem Rev, 2011, 111, 5899–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligresti, A., L. De Petrocellis, and V. Di Marzo, From Phytocannabinoids to Cannabinoid Receptors and Endocannabinoids: Pleiotropic Physiological and Pathological Roles Through Complex Pharmacology. Physiol Rev, 2016, 96, 1593–1659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Di Chiara, G. and A.Imperato, Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1988, 85, 5274–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, R.C. and V. Kumaresan, The mesolimbic dopamine system: the final common pathway for the reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse? Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2006, 30, 215–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillarp, N.A. Fuxe, and A.Dahlstrom, Demonstration and mapping of central neurons containing dopamine, noradrenaline, and 5-hydroxytryptamine and their reactions to psychopharmaca. Pharmacol Rev, 1966, 18, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roitman, M.F. , et al., Dopamine operates as a subsecond modulator of food seeking. J Neurosci, 2004, 24, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, P.E. , et al., Subsecond dopamine release promotes cocaine seeking. Nature, 2003, 422, 614–618. [Google Scholar]

- Cheer, J.F. , et al., Phasic dopamine release evoked by abused substances requires cannabinoid receptor activation. J Neurosci, 2007, 27, 791–795. [Google Scholar]

- Berridge, K.C. and T.E. Robinson, What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience? Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1998, 28, 309–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindra, D. , Neuropsychological interpretation of the effects of drive and incentive-motivation on general and instrumental behavior. Psychol Rev 1968, 75, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flagel, S.B. , et al., A selective role for dopamine in stimulus-reward learning. Nature 2011, 469, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nicola, S.M. , The flexible approach hypothesis: unification of effort and cue-responding hypotheses for the role of nucleus accumbens dopamine in the activation of reward-seeking behavior. J Neurosci, 2010, 30, 16585–16600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owesson-White, C.A. , et al., Neural encoding of cocaine-seeking behavior is coincident with phasic dopamine release in the accumbens core and shell. Eur J Neurosci, 2009, 30, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Koob, G.F. , Neurobiological substrates for the dark side of compulsivity in addiction. Neuropharmacology, 2009, 56 Suppl 1, 18-31.

- Weiss, F. , et al., Compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse. Neuroadaptation, stress, and conditioning factors. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2001, 937, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, J.M. , et al., Phasic Dopamine Signals in the Nucleus Accumbens that Cause Active Avoidance Require Endocannabinoid Mobilization in the Midbrain. Curr Biol, 2018, 28, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cheer, J.F. , et al., Cannabinoids enhance subsecond dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of awake rats. J Neurosci, 2004, 24, 4393–4400. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.P. , et al., Delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol produces naloxone-blockable enhancement of presynaptic basal dopamine efflux in nucleus accumbens of conscious, freely-moving rats as measured by intracerebral microdialysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 1990, 102, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Tanda, G. E.Pontieri, and G. Di Chiara, Cannabinoid and heroin activation of mesolimbic dopamine transmission by a common mu1 opioid receptor mechanism. Science, 1997, 276, 2048–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, E.D. , delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol excites rat VTA dopamine neurons through activation of cannabinoid CB1 but not opioid receptors. Neurosci Lett, 1997, 226, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessa, G.L. , et al., Cannabinoids activate mesolimbic dopamine neurons by an action on cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol, 1998, 341, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gantz, S.C. and B.P. Bean, Cell-Autonomous Excitation of Midbrain Dopamine Neurons by Endocannabinoid-Dependent Lipid Signaling. Neuron 2017, 93, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobi, A. , et al., Glutamatergic and nonglutamatergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area establish local synaptic contacts with dopaminergic and nondopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci, 2010, 30, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swanson, L.W. , The projections of the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions: a combined fluorescent retrograde tracer and immunofluorescence study in the rat. Brain Res Bull, 1982, 9, 321–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegel, A.C. and C.R. Lupica, Independent presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms regulate endocannabinoid signaling at multiple synapses in the ventral tegmental area. J Neurosci, 2004, 24, 11070–11078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, J.F. , et al., Lack of response suppression follows repeated ventral tegmental cannabinoid administration: an in vitro electrophysiological study. Neuroscience, 2000, 99, 661–667. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, B. Siemes, and I.Wallmichrath, Inhibition of GABAergic neurotransmission in the ventral tegmental area by cannabinoids. Eur J Neurosci, 2002, 15, 2057–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupica, C.R. and A.C. Riegel, Endocannabinoid release from midbrain dopamine neurons: a potential substrate for cannabinoid receptor antagonist treatment of addiction. Neuropharmacology 2005, 48, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperlagh, B. , et al., Neurochemical evidence that stimulation of CB1 cannabinoid receptors on GABAergic nerve terminals activates the dopaminergic reward system by increasing dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens. Neurochem Int, 2009, 54, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , et al., Crystal Structure of the Human Cannabinoid Receptor CB2. Cell, 2019, 176, 459–467. [Google Scholar]

- Augier, E. , et al., The GABA(B) Positive Allosteric Modulator ADX71441 Attenuates Alcohol Self-Administration and Relapse to Alcohol Seeking in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2017, 42, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar]

- van den Brink, W. , et al., Efficacy and safety of sodium oxybate in alcohol-dependent patients with a very high drinking risk level. Addict Biol, 2018, 23, 969–986. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbao, A. , et al., Endocannabinoid LTD in Accumbal D1 Neurons Mediates Reward-Seeking Behavior. iScience, 2020, 23, 100951. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , et al., Role of mGluR5 neurotransmission in reinstated cocaine-seeking. Addict Biol, 2013, 18, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olive, M.F. Metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands as potential therapeutics for addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev, 2009, 2, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M. , et al., Morphine disinhibits glutamatergic input to VTA dopamine neurons and promotes dopamine neuron excitation. Elife, 2015, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Laaris, N. H.Good, and C.R. Lupica, Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol is a full agonist at CB1 receptors on GABA neuron axon terminals in the hippocampus. Neuropharmacology, 2010, 59, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M. and S.A. Thayer, Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol acts as a partial agonist to modulate glutamatergic synaptic transmission between rat hippocampal neurons in culture. Mol Pharmacol, 1999, 55, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M. , et al., Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit glutamatergic synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal cultures. J Neurosci, 1996, 16, 4322–4334. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, W.J., O. M. Schluter, and Y. Dong, A Feedforward Inhibitory Circuit Mediated by CB1-Expressing Fast-Spiking Interneurons in the Nucleus Accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2017, 42, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Robbe, D. , et al., Localization and mechanisms of action of cannabinoid receptors at the glutamatergic synapses of the mouse nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci, 2001, 21, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Robbe, D. , et al., Endogenous cannabinoids mediate long-term synaptic depression in the nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2002, 99, 8384–8388. [Google Scholar]

- Zlebnik, N.E. and J.F. Cheer, Drug-Induced Alterations of Endocannabinoid-Mediated Plasticity in Brain Reward Regions. J Neurosci, 2016, 36, 10230–10238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M. , et al., Incentive learning underlying cocaine-seeking requires mGluR5 receptors located on dopamine D1 receptor-expressing neurons. J Neurosci, 2010, 30, 11973–11982. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, F.R. , et al., Immunolocalization of CB1 receptor in rat striatal neurons: a confocal microscopy study. Synapse, 2004, 53, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Basavarajappa, B.S. , et al., Endocannabinoid system in neurodegenerative disorders. J Neurochem, 2017, 142, 624–648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, R. , et al., FTD and ALS: a tale of two diseases. Curr Alzheimer Res 2011, 8, 273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, S.B. , et al., Familial clustering of ALS in a population-based resource. Neurology, 2014, 82, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. Al Khleifat, and A. Al-Chalabi, What causes amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? F1000Res, 2017, 6, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hely, M.A. , et al., Sydney Multicenter Study of Parkinson's disease: non-L-dopa-responsive problems dominate at 15 years. Mov Disord, 2005, 20, 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, W.G. , et al., Dementia in Parkinson's disease: a 20-year neuropsychological study (Sydney Multicentre Study). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2011, 82, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Ruiz, J. , et al., Ageing, Neurodegeneration and the Endocannabinoid System. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Meanti, R. , et al., Cannabinoid Receptor 2 (CB2R) as potential target for the pharmacological treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Biomed Pharmacother, 2025, 186, 118044. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, T.K. and I.A. Song, Impact of prescribed opioid use on development of dementia among patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Sci Rep, 2024, 14, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beheshti, I. , Cocaine Destroys Gray Matter Brain Cells and Accelerates Brain Aging. Biology 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolledo-Perez, L. , et al., Substance Abuse and Cognitive Decline: The Critical Role of Tau Protein as a Potential Biomarker. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B. , et al., Role of Alcohol Drinking in Alzheimer's Disease, Parkinson's Disease, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabia, S. , et al., Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: 23 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. BMJ, 2018, 362, k2927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koch, M. , et al., Alcohol Consumption and Risk of Dementia and Cognitive Decline Among Older Adults With or Without Mild Cognitive Impairment. JAMA Netw Open, 2019, 2, e1910319. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudet, G. , et al., Long-Lasting Effects of Chronic Intermittent Alcohol Exposure in Adolescent Mice on Object Recognition and Hippocampal Neuronal Activity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2016, 40, 2591–2603. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Infer, A. , et al., Effect of intermittent exposure to ethanol and MDMA during adolescence on learning and memory in adult mice. Behav Brain Funct, 2012, 8, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, L.G., Jr. , et al., Adolescent binge drinking alters adult brain neurotransmitter gene expression, behavior, brain regional volumes, and neurochemistry in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 2011, 35, 671–688. [Google Scholar]

- Rico-Barrio, I. , et al., Cognitive and neurobehavioral benefits of an enriched environment on young adult mice after chronic ethanol consumption during adolescence. Addict Biol, 2019, 24, 969–980. [Google Scholar]

- Montagud-Romero, S. , et al., The novelty-seeking phenotype modulates the long-lasting effects of intermittent ethanol administration during adolescence. PLoS One, 2014, 9, e92576. [Google Scholar]

- Guerri, C. and M.Pascual, Mechanisms involved in the neurotoxic, cognitive, and neurobehavioral effects of alcohol consumption during adolescence. Alcohol 2010, 44, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonso-Loeches, S. and C.Guerri, Molecular and behavioral aspects of the actions of alcohol on the adult and developing brain. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 2011, 48, 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espeland, M.A. , et al., Association between reported alcohol intake and cognition: results from the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. Am J Epidemiol, 2005, 161, 228–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli, M. , et al., Alcohol consumption and cognitive function in late life: a longitudinal community study. Neurology, 2005, 65, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer, M.J. , et al., Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cognitive function in women. N Engl J Med, 2005, 352, 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Stott, D.J. , et al., Does low to moderate alcohol intake protect against cognitive decline in older people? J Am Geriatr Soc, 2008, 56, 2217–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, E. , et al., Is there an association between low-to-moderate alcohol consumption and risk of cognitive decline? Am J Epidemiol, 2010, 172, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, F.S. , et al., The Impact of Alcohol Consumption on Cognitive Impairment in Patients With Diabetes, Hypertension, or Chronic Kidney Disease. Front Med (Lausanne), 2022, 9, 861145. [Google Scholar]

- Kabai, P. , Alcohol consumption and cognitive decline in early old age. Neurology, 2014, 83, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W. , et al., Association of moderate alcohol intake with in vivo amyloid-beta deposition in human brain: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med, 2020, 17, e1003022. [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan, M.R. , et al., Imaging beta-amyloid (Abeta) burden in the brains of middle-aged individuals with alcohol-use disorders: a [(11)C]PIB PET study. Transl Psychiatry, 2021, 11, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Mukamal, K.J. , et al., Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of dementia in older adults. JAMA, 2003, 289, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, D.G. , et al., The effect of alcohol and tobacco consumption, and apolipoprotein E genotype, on the age of onset in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2010, 25, 511–518. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, N. , et al., Alcohol and risk of Parkinson's disease in a large, prospective cohort of men and women. Mov Disord, 2012, 27, 980–987. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, A.K. , et al., Alcohol use disorders and risk of Parkinson's disease: findings from a Swedish national cohort study 1972-2008. BMC Neurol, 2013, 13, 190. [Google Scholar]

- Rotermund, C. , et al., Enhanced motivation to alcohol in transgenic mice expressing human alpha-synuclein. J Neurochem, 2017, 143, 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- D'Ovidio, F. , et al., Association between alcohol exposure and the risk of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in the Euro-MOTOR study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2019, 90, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, J. Silva, and A.Machado, Delayed Huntington's disease diagnosis in two alcoholic patients with a family history of "Parkinson's disease". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2010, 22, 451–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basavarajappa, B.S. , Endocannabinoid System and Alcohol Abuse Disorders. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2019, 1162, 89–127. [Google Scholar]

- Basavarajappa, B.S. , et al., Distinct functions of endogenous cannabinoid system in alcohol abuse disorders. Br J Pharmacol, 2019, 176, 3085–3109. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, A. and L.A.Natividad, Alcohol-Endocannabinoid Interactions: Implications for Addiction-Related Behavioral Processes. Alcohol Res, 2022, 42, 09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, S.A., V. Vozella, and M. Roberto, The Synaptic Interactions of Alcohol and the Endogenous Cannabinoid System. Alcohol Res, 2022, 42, 03. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Serrano, A. , et al., Deficient endocannabinoid signaling in the central amygdala contributes to alcohol dependence-related anxiety-like behavior and excessive alcohol intake. Neuropsychopharmacology, 2018, 43, 1840–1850. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, P. , et al., Pharmacological activation of CB2 receptors counteracts the deleterious effect of ethanol on cell proliferation in the main neurogenic zones of the adult rat brain. Front Cell Neurosci, 2015, 9, 379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bellozi, P.M.Q. , et al., URB597 ameliorates the deleterious effects induced by binge alcohol consumption in adolescent rats. Neurosci Lett, 2019, 711, 134408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Marin, L. , et al., Effects of Intermittent Alcohol Exposure on Emotion and Cognition: A Potential Role for the Endogenous Cannabinoid System and Neuroinflammation. Front Behav Neurosci, 2017, 11, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Erdozain, A.M. and L.F.Callado, Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in alcohol dependence: the biochemical, behavioral and genetic evidence. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2011, 117, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbanna, S. , et al., Anandamide-CB1 receptor signaling contributes to postnatal ethanol-induced neonatal neurodegeneration, adult synaptic, and memory deficits. J Neurosci, 2013, 33, 6350–6366. [Google Scholar]

- Subbanna, S. , et al., Postnatal ethanol exposure alters levels of 2-arachidonylglycerol-metabolizing enzymes and pharmacological inhibition of monoacylglycerol lipase does not cause neurodegeneration in neonatal mice. J Neurochem, 2015, 134, 276–287. [Google Scholar]

- Subbanna, S. , et al., Ethanol exposure induces neonatal neurodegeneration by enhancing CB1R Exon1 histone H4K8 acetylation and up-regulating CB1R function causing neurobehavioral abnormalities in adult mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2014, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Subbanna, S. , et al., CB1R-Mediated Activation of Caspase-3 Causes Epigenetic and Neurobehavioral Abnormalities in Postnatal Ethanol-Exposed Mice. Front Mol Neurosci, 2018, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Subbanna, S. and B.S. Basavarajappa, Postnatal Ethanol-Induced Neurodegeneration Involves CB1R-Mediated beta-Catenin Degradation in Neonatal Mice. Brain Sci 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagre, N.N. , et al., CB1-receptor knockout neonatal mice are protected against ethanol-induced impairments of DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNA methylation. J Neurochem, 2015, 132, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V. , et al., CB1R regulates CDK5 signaling and epigenetically controls Rac1 expression contributing to neurobehavioral abnormalities in mice postnatally exposed to ethanol. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basavarajappa, B.S. , et al., Elevation of endogenous anandamide impairs LTP, learning, and memory through CB1 receptor signaling in mice. Hippocampus 2014, 24, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma, J.C. , et al., Adolescent binge-ethanol accelerates cognitive impairment and beta-amyloid production and dysregulates endocannabinoid signaling in the hippocampus of APP/PSE mice. Addict Biol 2021, 26, e12883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Garcia, I. , et al., Preclinical investigation in FAAH inhibition as a neuroprotective therapy for frontotemporal dementia using TDP-43 transgenic male mice. J Neuroinflammation, 2023, 20, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnanz, M.A. , et al., Fatty acid amide hydrolase gene inactivation induces hetero-cellular potentiation of microglial function in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Glia, 2025, 73, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armeli, F. , et al., FAAH Inhibition Counteracts Neuroinflammation via Autophagy Recovery in AD Models. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galan-Ganga, M. , et al., Cannabinoid receptor CB2 ablation protects against TAU induced neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2021, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.H. A.Wiley, and C.W. Bradberry, Psychostimulant abuse and neuroinflammation: emerging evidence of their interconnection. Neurotox Res 2013, 23, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.B. B.Andrade, and P. Valentao, A Comprehensive View of the Neurotoxicity Mechanisms of Cocaine and Ethanol. Neurotox Res 2015, 28, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. , et al., Disrupted autophagy after spinal cord injury is associated with ER stress and neuronal cell death. Cell Death Dis 2015, 6, e1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, K.M. , et al., Unfolded proteins and endoplasmic reticulum stress in neurodegenerative disorders. J Cell Mol Med 2011, 15, 2025–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.M. , et al., Role of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in cocaine-induced microglial cell death. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2013, 8, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, P. L. Guo, and S.Buch, Cocaine induces astrocytosis through ER stress-mediated activation of autophagy. Autophagy 2016, 12, 1310–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.J. , et al., Alzheimer-like phosphorylation of tau and neurofilament induced by cocaine in vivo. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2003, 24, 512–518. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, R.E. Minnes, and L.T.Singer, Fetal Cocaine Exposure: Neurologic Effects and Sensory-Motor Delays. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 1996, 16, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C. , et al., Neuroprotection or Neurotoxicity of Illicit Drugs on Parkinson's Disease. Life (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, S. , et al., Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Cocaine's Neurotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, F.J. , et al., Direct binding and functional coupling of alpha-synuclein to the dopamine transporters accelerate dopamine-induced apoptosis. FASEB J 2001, 15, 916–926. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y. , et al., Cocaine abuse elevates alpha-synuclein and dopamine transporter levels in the human striatum. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 1489–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, L.O. , Psychomotor and electroencephalographic sequelae of cocaine dependence. NIDA Res Monogr, 1996, 163, 66–93. [Google Scholar]

- Argyriou, A.A. , et al., Cocaine use and abuse triggering sporadic young-onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurodegener Dis, 2011, 8, 146–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockhold, R.W. , Glutamatergic involvement in psychomotor stimulant action. Prog Drug Res, 1998, 50, 155–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heath, P.R. and P.J. Shaw, Update on the glutamatergic neurotransmitter system and the role of excitotoxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2002, 26, 438–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.K. , et al., Liposomal melatonin rescues methamphetamine-elicited mitochondrial burdens, pro-apoptosis, and dopaminergic degeneration through the inhibition PKCdelta gene. J Pineal Res, 2015, 58, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, M. and B.Vincent, The multi-faceted impact of methamphetamine on Alzheimer's disease: From a triggering role to a possible therapeutic use. Ageing Res Rev, 2020, 60, 101062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado, N. Ares-Santos, and R.Moratalla, Methamphetamine and Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis, 2013, 2013, 308052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ares-Santos, S. Granado, and R.Moratalla, The role of dopamine receptors in the neurotoxicity of methamphetamine. J Intern Med 2013, 273, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares-Santos, S. , et al., Methamphetamine causes degeneration of dopamine cell bodies and terminals of the nigrostriatal pathway evidenced by silver staining. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014, 39, 1066–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. , et al., Methamphetamine exposure upregulates the amyloid precursor protein and hyperphosphorylated tau expression: The roles of insulin signaling in SH-SY5Y cell line. J Toxicol Sci 2019, 44, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, R.C. , et al., Increased risk of Parkinson's disease in individuals hospitalized with conditions related to the use of methamphetamine or other amphetamine-type drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012, 120, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagioni, F. , et al., Methamphetamine persistently increases alpha-synuclein and suppresses gene promoter methylation within striatal neurons. Brain Res 2019, 1719, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Ruiz, J. A.Moro, and J. Martinez-Orgado, Cannabinoids in Neurodegenerative Disorders and Stroke/Brain Trauma: From Preclinical Models to Clinical Applications. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Ruiz, J. Romero, and J.A. Ramos, Endocannabinoids and Neurodegenerative Disorders: Parkinson's Disease, Huntington's Chorea, Alzheimer's Disease, and Others. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2015, 231, 233–259. [Google Scholar]

- Marsicano, G. , et al., CB1 cannabinoid receptors and on-demand defense against excitotoxicity. Science 2003, 302, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Moncada, I. , et al., Type-1 cannabinoid receptors and their ever-expanding roles in brain energy processes. J Neurochem 2024, 168, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenfeld, R. and L.A.Devi, Regulation of CB1 cannabinoid receptor trafficking by the adaptor protein AP-3. FASEB J, 2008, 22, 2311–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailoiu, G.C. , et al., Intracellular cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptors are activated by anandamide. J Biol Chem, 2011, 286, 29166–29174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arevalo-Martin, A. , et al., CB2 cannabinoid receptors as an emerging target for demyelinating diseases: from neuroimmune interactions to cell replacement strategies. Br J Pharmacol, 2008, 153, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.M. , et al., CB(1) receptor activation inhibits neuronal and astrocytic intermediary metabolism in the rat hippocampus. Neurochem Int, 2012, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Holgado, F. , et al., Endogenous interleukin-1 receptor antagonist mediates anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions of cannabinoids in neurons and glia. J Neurosci 2003, 23, 6470–6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, N. , Cannabinoid and cannabinoid-like receptors in microglia, astrocytes, and astrocytomas. Glia, 2010, 58, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, C. , et al., Cannabinoid CB2 receptors and fatty acid amide hydrolase are selectively overexpressed in neuritic plaque-associated glia in Alzheimer's disease brains. J Neurosci, 2003, 23, 11136–11141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, G.A. and L. Griffin-Thomas, Emerging role of the cannabinoid receptor CB2 in immune regulation: therapeutic prospects for neuroinflammation. Expert Rev Mol Med, 2009, 11, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, T. , et al., Cannabinoid Receptor 2 Signaling in Neurodegenerative Disorders: From Pathogenesis to a Promising Therapeutic Target. Front Neurosci 2017, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoppi, S. , et al., Regulatory role of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor in stress-induced neuroinflammation in mice. Br J Pharmacol, 2014, 171, 2814–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.Y. , et al., Activation of cannabinoid CB2 receptor-mediated AMPK/CREB pathway reduces cerebral ischemic injury. Am J Pathol 2013, 182, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechoulam, R. and E.Shohami, Endocannabinoids and traumatic brain injury. Mol Neurobiol, 2007, 36, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendel, E. and E.C. de Lange, Functions of the CB1 and CB 2 receptors in neuroprotection at the level of the blood-brain barrier. Neuromolecular Med 2014, 16, 620–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haj-Dahmane, S. and R.Y. Shen, Modulation of the serotonin system by endocannabinoid signaling. Neuropharmacology 2011, 61, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, M. , et al., Cannabinoid type 2 receptor stimulation attenuates brain edema by reducing cerebral leukocyte infiltration following subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. J Neurol Sci, 2014, 342, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, K. Varelas, and H.Zheng, Endocannabinoid System of the Blood-Brain Barrier: Current Understandings and Therapeutic Potentials. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res, 2022, 7, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).