1. Introduction

Rare diseases collectively affect more than 300 million people worldwide, yet each individual condition has a very low prevalence and limited evidence base [

1,

2]. Patients with rare diseases often endure a prolonged diagnostic odyssey, which can last several years and involve multiple misdiagnoses and repeated consultations before a correct diagnosis is reached [

3]. This is compounded by a shortage of specialized clinicians, concentration of expertise in a few tertiary centers, and inequitable access to advanced diagnostic tools such as genomic sequencing [

4]. Health systems may lack standardized referral pathways, interoperable registries, and coordinated care models, resulting in fragmentation, duplication of efforts, and unmet patient needs [

5].

Second medical opinions (SO) represent an essential mechanism to address these challenges. By enabling patients and healthcare providers to obtain an additional expert assessment of diagnosis or treatment options, SO can increase diagnostic accuracy, improve treatment planning, reduce unnecessary interventions, and enhance patient trust. In the context of rare diseases, SO is especially critical because expertise is scarce and dispersed, clinical guidelines are often absent or incomplete, and management decisions may have life-changing consequences [

6].

The digital transformation of healthcare has facilitated new structured models of second opinion delivery, such as tele-expertise, virtual multidisciplinary team meetings (vMDTs), e-consult platforms, and secure reference networks. Unlike direct-to-patient teleconsultations, these systems prioritize clinician-to-clinician exchange, often incorporating formal workflows, eligibility criteria, patient consent, governance, and data protection rules, as well as standardized documentation of recommendations [

7,

8]. Reported benefits include diagnostic revision, treatment modification, shared care coordination, capacity building of local providers, and increased equity of access [

6,

8,

9].

Despite these advances, the literature remains fragmented. Initiatives differ in scope (disease-specific vs. cross-disease), modality (synchronous vs. asynchronous), governance models, financing, and outcome reporting. Terminology is inconsistent, with overlapping use of second opinion, tele-expertise, virtual consultation, or reference network, hindering synthesis and comparability. Furthermore, there is limited mapping of which systems are available, how they operate, what outcomes they achieve, and which barriers and facilitators shape their implementation [

10].

It is also essential to distinguish SO from related concepts. Teleconsultation generally refers to direct clinical interactions between a patient and a healthcare provider via telecommunication tools [

11]. Tele-expertise, also known as e-consult, involves clinician-to-clinician exchanges, often asynchronous, to obtain specialist input without the patient being present [

12]. vMDTs represent another modality, where multiple experts discuss a case together in real time, usually through secure online platforms [

13]. Although terminology varies across contexts, all these models can serve as structured mechanisms of SO if they follow defined processes of case submission, discussion, and recommendation.

In this context, a scoping review is warranted to map and characterize digital systems, processes, and platforms that deliver second medical opinions in rare diseases. Specifically, this review aims to: (i) describe the types of models; (ii) characterize the populations and actors involved; (iii) extract key components of system design and operation; (iv) summarize reported outcomes; and (v) identify barriers, facilitators, and gaps for future research and policy.

Guided by a population–concept–context framing, this review addresses people living with rare diseases and the clinicians who care for them (population), structured second-opinion systems and their workflows, governance, technology, adoption, and reported impacts (concept), and real-world healthcare services and networks operating at regional, national, cross-border, and international levels (context). Our objective is to map how second-opinion services for rare diseases are designed and governed, how they are adopted and used, and what outcomes are reported.

2. Materials and Methods

Scoping reviews are ideal for providing an overview of a given topic, determining its coverage, and clearly indicating the volume of literature and studies available [

14]. This review followed the methodological framework initially proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [

15] and further refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [

16], which recommends a five-stage process. In the following subsections, each stage is described in detail. Reporting adhered to the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [

17].No review protocol was registered for this scoping review.

2.1. Stage 1: Identifying the Objective and Research Questions

For this review, SO is considered in a more structured and system-based sense: a formalized process where clinicians present a patient case to another specialist or multidisciplinary panel, often supported by digital platforms, standardized workflows, and documented recommendations. This excludes isolated individual requests or case reports, which lack systematization and reproducibility.

The objective of this review was to explore and characterize structured systems, processes, and platforms designed to deliver second medical opinions (SO) in the context of rare and orphan diseases. The following research questions guided the review:

Q1. What types of digital systems, processes, or platforms have been developed and implemented to provide second medical opinions in rare and orphan diseases, and at what organizational scale (national, regional, international)?

Q2. What are the main design features, workflows, and governance elements of these systems, including interoperability and ethical/legal safeguards?

Q3. What outcomes, benefits, and limitations have been reported in clinical practice and policy, including diagnostic/therapeutic impact, time to decision, user satisfaction, and cost/resource implications?

Q4. What barriers, facilitators, and sustainability factors have been identified for the implementation and long-term adoption of these systems, and what research gaps remain?

2.2. Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

At this stage, the search strategy, i.e., the selected databases and keywords, as well as the eligibility criteria for assessing each primary study, were defined to narrow the search and identify relevant studies.

Search strategy. The literature search was carried out in August 2025. The selected databases include PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane Library, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and LILACS, covering both biomedical and technology-focused sources. In all databases, we combined terms for second medical opinion and virtual/multidisciplinary consultations with terms for rare diseases. No date limits were applied; results were restricted to English, Portuguese, or Spanish. No study-design or publication-type filters were used, consistent with a scoping-review approach. The complete reproducible PubMed/MEDLINE strategy is reported below:

("Second Opinion"[Mesh] OR "second opinion"[tiab] OR "second opinions"[tiab]

OR tele-expertise[tiab] OR e-consult*[tiab] OR "virtual consultation*"[tiab]

OR "virtual case discussion*"[tiab] OR "multidisciplinary team"[tiab] OR vMDT[tiab])

AND ("Rare Diseases"[Mesh] OR "rare disease*"[tiab] OR "orphan disease*"[tiab] OR Orphanet[tiab])

AND (english[lang] OR portuguese[lang] OR spanish[lang])

Eligibility criteria. Eligibility criteria were defined according to the PCC (Population–Concept–Context) framework. We included studies that: (i) explicitly addressed second medical opinions in the context of rare or orphan diseases, involving patients, caregivers, or healthcare professionals; (ii) described or evaluated a structured system, platform, or organizational process for delivering second opinions (e.g., virtual multidisciplinary team meetings, e-consult/tele-expertise platforms, reference networks, or web-based submission systems); and (iii) were implemented in real healthcare settings. We excluded isolated case reports, telemedicine or telegenetics initiatives not explicitly focused on second opinions, conceptual proposals without implementation, and studies conducted outside the field of rare diseases.

Forward and backward searching. To complement database searches, forward and backward citation tracking was performed on all included studies to identify additional relevant articles that may have been left out.

2.3. Stage 3: Study Selection

All references were imported into Rayyan for data management and deduplication [

18]. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility. Articles deemed potentially relevant proceeded to full-text screening, also performed independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. Reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage were documented. PRISMA-ScR flow diagram was used to report the selection process.

2.4. Stage 4: Charting the data

A standardized data extraction form was designed to capture the information required to address the research questions. The data charting process was piloted on a subset of studies and refined accordingly.

Table 1 indicates the type of data that were extracted from each included article.

2.5. Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Data from the included studies were collated and synthesized descriptively. Findings were summarized in a table and narrative form, organized by type of second opinion system, disease area, and reported outcomes. Similarities and differences across studies were examined to identify patterns, themes, and gaps. No formal quality appraisal was conducted, consistent with scoping review methodology.

3. Results

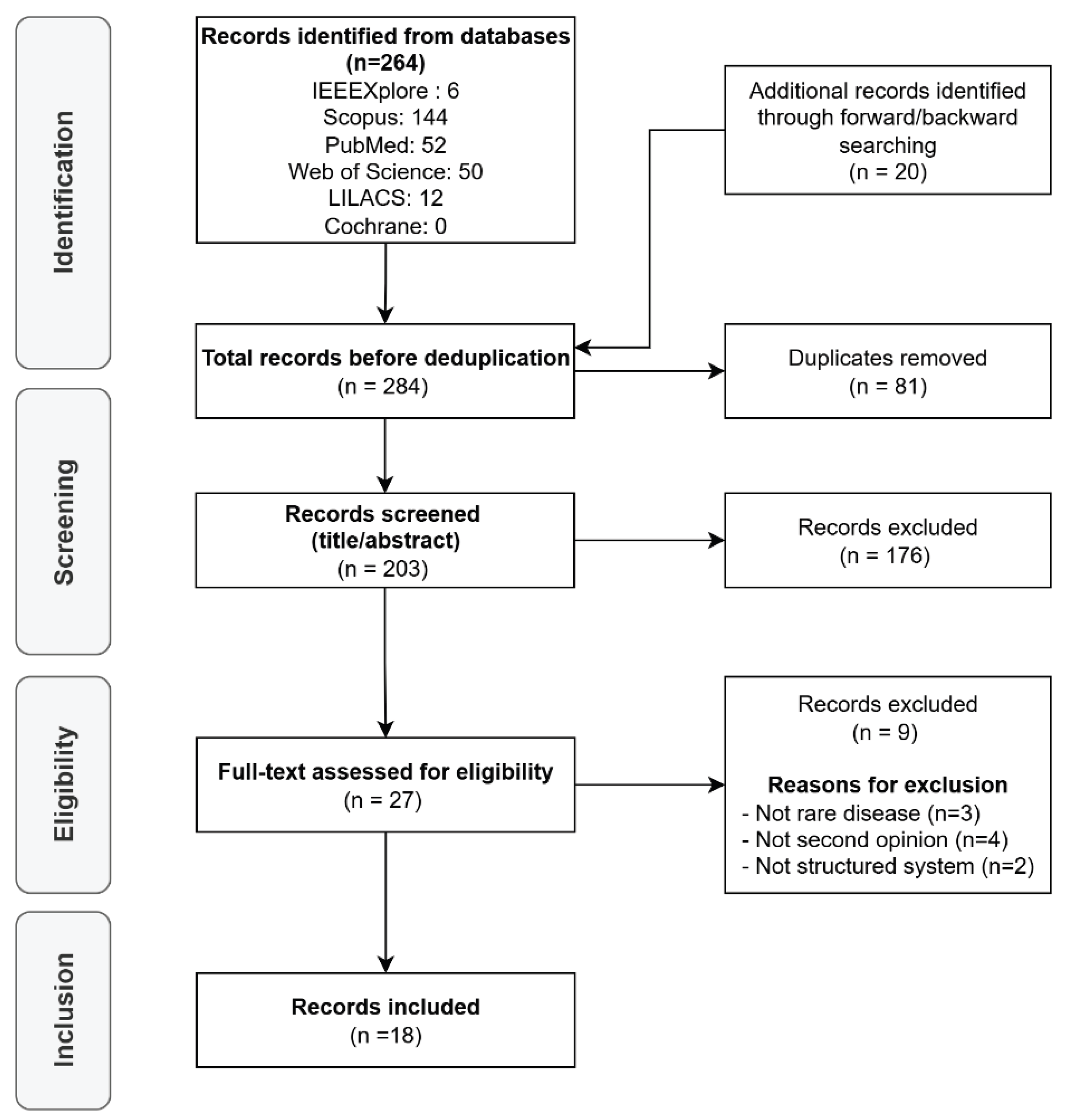

Initially, 264 articles were retrieved from the selected databases, and 20 were identified through forward and backward citation searching (a total of 284 records). After removing 81 duplicates, 203 records remained for screening. Following the title and abstract assessment, 176 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 27 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 9 were excluded: 3 did not focus on rare diseases, 4 did not address second opinions, and 2 lacked a structured system or platform. Finally, 18 studies were included in this scoping review.

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram, and the per-study characteristics and all charted variables for each included source of evidence are provided in Supplementary Spreadsheet S1.

To avoid overlap, we organized results by implementation scale, a dimension that cleanly separates governance, legal frameworks, and interoperability models. Distribution by scale was as follows: European Research Networks (ERN) (8/18), National (5/18), Regional (2/18), and International (3/18). Regarding the technological approach, hybrid modalities predominated (9/18), followed by asynchronous (6/18) and synchronous contexts (3/18). Clinical domains were diverse, with concentrations in pediatric oncology (5/18) and clinical genetics/dysmorphology (5/18), alongside neurology/neuromuscular (3/18), endocrinology (2/18), immunology (1/18), urology (1/18), and cross-cutting platforms (1/18).

3.1. Cross-Border ERN Systems

ERN initiatives converge on the Clinical Patient Management System (CPMS) or direct precursors. Activity ranged from early implementation with a few dozen cases to mature programs with more than 150 panels. Examples include pediatric very-rare tumors integrating from EXPeRT to ERN PaedCan/CPMS (160 cases across 27 countries, 56 centers) [

19], and ERN eUROGEN (152 panels; 81% closed) [

20]. Endo-ERN reported growth to 144 panels with 326 registered and 270 active users [

21], while EURO-NMD demonstrated a training-driven scale-up (panels 23→120 in 12 months) [

22]. ERN-RND documented pan-European uptake (>40 CPMS discussions in early phase) [

23], and ITHACA summarized its first-year telemedicine experience [

24]. ExPO-r-Net mapped European pediatric tumor-board readiness as a baseline for ERN deployment (121 institutions; virtual capability still limited at that time) [

25].

Impacts. Across ERNs, reported impacts cluster around treatment/diagnosis decision-making and faster access to expertise. In EXPeRT/PaedCan, 93% of consultations influenced management; advice was thoroughly followed in 83% and partly in 14%, with typical responses in 2–3 days [

19]. Endo-ERN users rated the usefulness high (approximately 8/10), with management changes or validations in roughly two-thirds of cases [

26]. ERN eUROGEN emphasized optimization of care pathways [

20]. Training effects, such as increased platform confidence and sustained usage, were consistently observed [

21,

22].

Governance, workflow, interoperability. ERN systems share a role-based workflow (case submission → panel coordination → multidisciplinary discussion → outcome document), under GDPR-compliant consent and audit trails. Video meetings are available, but most casework remains asynchronous (structured forms, threaded comments), with DICOM/image upload and standardized datasets. Interoperability with registries (e.g., EuRRECa/e-REC in Endo-ERN) is emerging; direct linkage of Electronic Health Records (EHR) is generally planned rather than routine.

Barriers and enablers. Recurrent barriers include platform complexity, time burden for panel creation, limited incentives, and uneven onboarding/awareness. Enablers are helpdesk support, targeted training, standardized consent across ERNs, and the multidisciplinary network effect. Sustainability leans on European Commission funding streams and the progressive integration of ERNs into national systems [

20,

21].

3.2. National Systems

National programs tailor governance and processes to local legal and service contexts. Italy’s IEI-VCS/IPINet validated 68 cases, reaching a final diagnosis in ~51% (with many genetically confirmed) [

27]. The UK’s National Advisory Panels (NAPs) reviewed over 1,100 referrals, with approximately 89% of recommendations implemented, and typical referral-to-panel and panel-to-recommendation intervals of 10 days and 4 days, respectively [

28]. Germany’s GPOH rare tumor network demonstrated early activity and substantial improvements in case registration and knowledge sharing [

29]. Spain’s national survey showed widespread vMDT presence but uneven virtual capacity and standardization [

30]. Brazil’s RD2O is a cross-cutting platform in development/pilot, aligned with national rare-disease networks [

31].

Impacts. Reported national-level benefits include diagnostic yield (e.g., IEI-VCS), changes to or validation of local plans (UK NAPs), and faster access to reference expertise (GPOH). Surveys highlight where impact is latent but dependent on standardizing documentation, quoracy, and follow-through (Spain).

Governance, workflow, interoperability. Common patterns include standardized referral proformas, panel chairs/administrators, and clear statements that legal responsibility remains with the treating team. Interoperability varies, with national registries and PACS being common, while unified virtual platforms and EHR integration are less consistent.

Barriers and enablers. Key gaps are Standard Operating Procedures (SOP), protected time, defined quorum, and secure data platforms to support audit and learning. Enablers include national networks/registries, central reviews (such as radiology/pathology), and emerging guidance that formalizes referral and documentation processes.

3.3. Regional Systems

Subnational networks demonstrate how coordinated hybrid workflows can yield significant operational benefits. Italy’s NOVHO (Lombardy) discussed 80 patients in 28 meetings across 6 centers [

32]; the USA’s Consultagene/Project GIVE enrolled 196 referrals in an underserved region with bilingual navigation and clinic-embedded tele-genetics [

33].

Impacts. NOVHO reported a 66% reduction in time to assessment (≈89→30 days), 47% fewer hospital visits (141 avoided across 80 patients), and a 27.5% reduction in diagnostic revisions. GIVE increased access to genetics services and workforce capability (outcomes pending), illustrating the role of local cultural and language mediation.

Governance, workflow, interoperability. Both rely on structured submission, case management, and regular multidisciplinary case-conferences, with emphasis on local logistics (e.g., imaging sharing; clinic kiosks) rather than national infrastructure.

Barriers and enablers. Persistent barriers include IT constraints, time/scheduling issues, and limitations of remote physical examination. Enablers include clear roles, routine case rounds, and on-site coordination to bridge digital and in-clinic steps.

3.4. International Programs

Outside the ERN architecture, programs span bilateral telegenetics and pan-European crowdsourcing in dysmorphology. The DR-USA telegenetics program saw 66 individuals over five years with regular, scheduled clinics [

34]. DYSCERNE’s web-based diagnostic system handled 200 consecutive cases in a formal evaluation and sustained ~8 cases/month in service mode [

35,

36].

Impacts. Telegenetics achieved a 59% molecular diagnosis rate and approximately 70% management recommendations, with scheduling typically occurring within ~2 weeks. DYSCERNE’s consensus clinical diagnosis rate was 22.5%, with a 36-day turnaround, frequent test recommendations (e.g., genetic testing in ~70%), and identification of new syndromic entities. Operating costs were about 127€/case, underscoring cost-effective reach.

Governance, workflow, interoperability. Submissions are standardized, consent is explicit for images/data, and expert panels provide written reports. Interoperability is modest (secure portals, archives); direct EHR linkage is generally absent.

Barriers and enablers. Sustainability beyond initial grants is the dominant challenge (expert time, platform upkeep, engagement), whereas enablers include clear protocols, educational spillover for submitters/reviewers, and network effects from multinational expertise.

4. Discussion

This scoping review synthesizes the evolution of structured second-opinion systems for rare diseases from locally organized advisory groups into multi-level, digitally enabled networks with reproducible workflows and auditable governance. Across ERNs, national programs, regional initiatives, and international collaborations, a standard operating model emerged: structured submission, eligibility screening and triage, moderated multidisciplinary deliberation that is primarily asynchronous with optional video, and a signed-off recommendation with responsibility retained by the treating clinician, yet implementation choices diverged according to scale, legal frameworks, and available infrastructure [

19,

21,

22,

24,

28,

34,

36]. Interpreting these findings together suggests that ERN-style governance and consent models enable cross-border collaboration at scale. At the same time, national and regional services can move more quickly on local logistics and workforce embedding, while international outreach programs can close equity gaps in underserved settings.

A first implication concerns decision quality and timeliness. Multiple ERN reports, spanning very rare pediatric tumors, endocrinology, neurology and neuromuscular disease, and urology, describe consistent influence on diagnostic and therapeutic plans, high perceived usefulness, and accelerated access to subspecialty expertise through CPMS or its precursors [

19,

20,

22,

23,

24,

25,

37]. At the national level, the UK National Advisory Panels achieved widespread adoption, with high implementation of recommendations, underscoring the value of standardized intake, chaired moderation, and rapid post-meeting documentation [

28]. Regional initiatives, such as the virtual hospital for rare cerebrovascular diseases, reduced time to assessment and unnecessary hospital visits while revising a substantial share of diagnoses, illustrating how subnational networks can reconfigure care pathways when case volumes concentrate across a few centers [

32]. International telegenetics programs demonstrate both high diagnostic yield, where sequencing is accessible and pragmatic turnaround times, while also building local capability through case-based learning [

33,

34,

35,

36].

A second implication relates to governance, data protection, and interoperability. ERN deployments share role-based access control, GDPR-aligned multi-stage consent, structured datasets, and traceable outcome notes, lowering transaction costs for cross-border working [

21,

24]. Where integration exists today, it most often connects panels to disease registries rather than to hospital EHRs; many programs describe bidirectional EHR interoperability as a near-term goal rather than a routine capability [

20,

21]. National and regional services demonstrate that interoperability is not a binary concept: imaging repositories and PACS integration are standard, but unified virtual platforms and EHR links remain uneven, and medico-legal clarity outside ERNs requires explicit local arrangements [

28,

29,

30]. International programs rely on secure portals and explicit image/data consent, trading deep systems integration for reach and feasibility in resource-constrained contexts [

34,

35,

36].

A third implication concerns adoption and sustainability. Across settings, uptake is most substantial where helpdesks, hands-on training, and clear SOPs reduce cognitive and administrative load; where expert effort is recognized in job planning; and where panel coordination is resourced rather than informal [

21,

22,

28]. Conversely, recurring frictions, such as platform complexity, time-intensive panel creation, inconsistent incentives, and uneven institutional buy-in, quickly translate into underuse, even when perceived clinical value is high [

20,

21,

30]. International crowdsourcing in dysmorphology further highlights the importance of sustainable funding and reviewer capacity; a modest cost per case can still be untenable if revenue and incentives are not aligned with demand [

35,

36]. Regional and outreach programs surface additional equity-relevant constraints (e.g., technology access, digital literacy, and limits of remote examination) that can be mitigated but not eliminated through on-site coordination and bilingual navigation [

33,

34].

This synthesis has limitations. First, the evidence base is mainly observational and programmatic; most studies rely on descriptive metrics and user-reported usefulness rather than controlled comparisons or patient-level outcomes, limiting causal inference. Second, interoperability and sustainability claims are often prospective, and several papers report planned EHR integration or anticipated funding solutions rather than audited implementations, which may inflate expectations. Third, our corpus consists of 18 studies provided for extraction, which means the sampling is purposive rather than exhaustive. The review may under-represent negative or null experiences, non-English publications, and grey literature. Fourth, contextual factors, such as national data-protection practices, may limit generalizability. ERN experiences, for instance, may not transplant directly to non-EU health systems. Finally, several programs report early-phase or pilot data, so implementation trajectories and long-term outcomes may differ as systems mature.

The rationale for using a scoping review rests on the maturity and heterogeneity of this field. The interventions vary widely in scope (ERN, national, regional, international), technical modality (asynchronous, synchronous, hybrid), disease area, governance, and outcome definitions. Guidance explicitly recommends scoping reviews when topics are conceptually broad, evidence is methodologically diverse, and many sources are descriptive or programmatic rather than comparative, making meta-analysis inappropriate or premature [

14]. Accordingly, a scoping approach is best suited to map the breadth and nature of evidence, clarify concepts and workflow components, and identify gaps and priorities for future evaluative research [

15].

Additionally, focusing the scoping review exclusively on second-opinion systems for rare diseases is justified by the low prevalence, dispersed expertise, and high diagnostic uncertainty. Rare diseases frequently require cross-border or inter-institutional deliberation to reach and validate management decisions. This creates a structural need for system-level SO services, explaining why the most mature digital infrastructures and governance models have emerged in ERNs.

These constraints notwithstanding, the review points to concrete, testable priorities. Usability and incentives should be aligned so that expert participation is technically straightforward and formally recognized within service planning, aligned with clinical workflows, and consistent with professional well-being [

38]. Interoperability should progress from registry bridges toward safe, standardized, and, where appropriate, bidirectional EHR connectivity that enables longitudinal follow-up and comparative effectiveness while preserving privacy, leveraging open standards such as HL7 FHIR/SMART to enable longitudinal tracking and comparative analysis with privacy protection [

39]. Evaluation should shift from perceived usefulness to prospective, patient-level metrics, supported by consistent data elements and audit trails across programs, anchored in consolidated implementation/evaluation frameworks and WHO guidelines for digital health assessment [

40,

41]. Finally, equity-oriented design, including bilingual navigation, clinic-embedded kiosks, and clear escalation pathways for in-person assessment, should be treated as core infrastructure rather than optional features in regions where access barriers are structural [

42,

43].

In sum, the field has established a workable minimum viable workflow for second-opinion services in rare diseases and demonstrated clinical relevance across scales. The next phase requires disciplined attention to human-centered design and incentives, pragmatic interoperability that builds from registries toward EHRs, and outcome frameworks that verify patient benefit and value for money. ERNs provide a template for governance and consent, national and regional services demonstrate how to operationalize logistics, and international outreach programs maintain a focus on equity. Together, these strands outline a realistic path to scale without compromising clinical rigor or fairness.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review demonstrates that structured second-opinion systems for rare diseases have evolved from ad-hoc consultations into multi-level, digitally enabled services with reproducible and auditable workflows. Across cross-border networks, national programs, regional “virtual hospital” models, and international outreach, we observed a stable operating backbone. Despite variations in scale, legal context, and technology, the signals of benefit were consistent: faster access to subspecialty expertise, shorter decision times, frequent clarification or adjustment of diagnostic and therapeutic plans, and educational spillovers for the workforce.

For implementation, the clearest lessons are practical. Programs that pair strong governance with day-to-day enablers achieve steadier uptake and more reliable follow-through. Equity-oriented design, such as bilingual navigation, clinic-embedded kiosks, and clear escalation to in-person assessment, should be treated as core infrastructure in settings where digital and geographic barriers are structural. For evaluation, the field should move beyond perceived usefulness toward prospective, patient-level outcomes and comparative effectiveness.

These conclusions are bounded by a heterogeneous, mostly descriptive evidence base and a purposive sample of studies. Even so, the overall picture is clear, showing that systematized second-opinion services for rare diseases are feasible, clinically relevant, and scalable when usability, incentives, and interoperability are addressed together. With disciplined attention to human-centered design, sustainable resourcing of expertise, and data standards that protect privacy while enabling measurement, these services provide a practical path to reduce unwarranted variation, accelerate diagnosis, and advance equity without shifting clinical responsibility away from the point of care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Spreadsheet S1: Structured data extraction of the 18 studies included in the scoping review on second-opinion systems for rare diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L. and D.A.; Methodology, V.L. and D.A.; Software, —; Validation, V.L., M.M., and D.A.; Formal Analysis, V.L.; Investigation, V.L. and M.M.; Resources, D.A.; Data Curation, V.L. and M.M.; Writing - Original Draft Preparation, V.L.; Writing - Review & Editing, V.L., M.M., and D.A.; Visualization, V.L.; Supervision, D.A.; Project Administration, D.A.; Funding Acquisition, D.A.

Funding

The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) supports this project (grant no. 2023/10203-8 and 2024/22679-0). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nguengang Wakap S, Lambert DM, Olry A, Rodwell C, Gueydan C, Lanneau V, et al. Estimating cumulative point prevalence of rare diseases: analysis of the Orphanet database. European Journal of Human Genetics 2020;28:165–73. [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Global Health. The landscape for rare diseases in 2024. Lancet Glob Health 2024.

- Marwaha S, Knowles JW, Ashley EA. A guide for the diagnosis of rare and undiagnosed disease: beyond the exome. Genome Med 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Baynam G, Hartman AL, Catherine M, Letinturier V, Bolz-Johnson M, Carrion P, et al. Global health for rare diseases through primary care. vol. 12. 2024.

- Morris S, Walton H, Simpson A, Leeson-Beevers K, Bloom L, Hunter A, et al. Preferences for coordinated care for rare diseases: discrete choice experiment. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2024;19. [CrossRef]

- Chen FH, Hartman AL, Letinturier MC V., Antoniadou V, Baynam G, Bloom L, et al. Telehealth for rare disease care, research, and education across the globe: A review of the literature by the IRDiRC telehealth task force. Eur J Med Genet 2024;72. [CrossRef]

- Scherr JF, Albright C, de los Reyes E. Utilizing telehealth to create a clinical model of care for patients with Batten disease and other rare diseases. Therapeutic Advances in Rare Disease 2021;2. [CrossRef]

- Ducrocq Q, Guédon-Moreau L, Launay D, Terriou L, Morell-Dubois S, Maillard H, et al. Activities of Clinical Expertise and Research in a Rare Disease Referral Centre: A Place for Telemedicine beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic? Healthcare (Switzerland) 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Morris S, Hudson E, Bloom L, Chitty LS, Fulop NJ, Hunter A, et al. Co-ordinated care for people affected by rare diseases: the CONCORD mixed-methods study. Health and Social Care Delivery Research 2022;10:vii–220. [CrossRef]

- Olowu A. Innovative telemedicine technology usage in rare diseases management in primary care in a COVID-19 pandemic era: Lessons learnt and recommendations for future practice. Journal of Endocrinological Science 2023.

- Maria ARJ, Serra H, Heleno B. Teleconsultations and their implications for health care: A qualitative study on patients’ and physicians’ perceptions. Int J Med Inform 2022;162. [CrossRef]

- Heudel P, Amini-Adle M, Anriot J, Vaz G, Laine C, Desoutter A, et al. The impact of tele-expertise in oncology: current state and future perspectives. Front Digit Health 2025;7. [CrossRef]

- Munro AJ, Swartzman S. What is a virtual multidisciplinary team (vMDT)? Br J Cancer 2013;108:2433–41. [CrossRef]

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice 2005;8:19–32. [CrossRef]

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. [CrossRef]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5. [CrossRef]

- Schneider DT, Ferrari A, Orbach D, Virgone C, Reguerre Y, Godzinski J, et al. A virtual consultation system for very rare tumors in children and adolescents – an initiative of the European Cooperative Study Group in Rare Tumors in Children (EXPeRT). EJC Paediatric Oncology 2024;3. [CrossRef]

- Oomen L, Leijte E, Shilhan DE, Battye M, Feitz WFJ. Cross-Border Video Consultation Tool for Rare Urology: ERN eUROGEN’s Clinical Patient Management System. n.d.

- White EK, Wagner I V., van Beuzekom C, Iotova V, Ahmed SF, Hiort O, et al. A critical evaluation of the EU-virtual consultation platform (CPMS) within the European Reference Network on Rare Endocrine Conditions. Endocr Connect 2022;11. [CrossRef]

- Fortunato F, Bianchi F, Ricci G, Torri F, Gualandi F, Neri M, et al. Digital health and Clinical Patient Management System (CPMS) platform utility for data sharing of neuromuscular patients: the Italian EURO-NMD experience. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2023;18. [CrossRef]

- Reinhard C, Bachoud-Lévi AC, Bäumer T, Bertini E, Brunelle A, Buizer AI, et al. The European Reference Network for Rare Neurological Diseases. Front Neurol 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Smith M, Alexander E, Marcinkute R, Dan D, Rawson M, Banka S, et al. Telemedicine strategy of the European Reference Network ITHACA for the diagnosis and management of patients with rare developmental disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020;15. [CrossRef]

- Juan Ribelles A, Berlanga P, Schreier G, Nitzlnader M, Brunmair B, Castel V, et al. Survey on paediatric tumour boards in Europe: current situation and results from the ExPo-r-Net project. Clinical and Translational Oncology 2018;20:1046–52. [CrossRef]

- Mönig I, Steenvoorden D, de Graaf JP, Ahmed SF, Taruscio D, Beun JG, et al. CPMS–improving patient care in Europe via virtual case discussions. Endocrine 2021;71:549–54. [CrossRef]

- Coppola E, Sgrulletti M, Cortesi M, Romano R, Cirillo E, Giardino G, et al. The Inborn Errors of Immunity—Virtual Consultation System Platform in Service for the Italian Primary Immunodeficiency Network: Results from the Validation Phase. J Clin Immunol 2024;44. [CrossRef]

- Brown S, Chowdhury T, Collin M, Grundy RG, Howell L, Ramanujachar R, et al. National advisory panels for childhood cancer in the United Kingdom: An evaluation of current practice and a best practice statement for the future. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2023;70. [CrossRef]

- Brecht IB, Graf N, Schweinitz D Von, Frühwald MC, Bielack SS, Schneider DT. Networking for children and adolescents with very rare tumors: Foundation of the gpoh pediatric rare tumor group. Klin Padiatr 2009;221:181–5. [CrossRef]

- Berlanga P, Segura V, Juan Ribelles A, Sánchez de Toledo P, Acha T, Castel V, et al. Paediatric tumour boards in Spain: a national survey. Clinical and Translational Oncology 2016;18:931–6. [CrossRef]

- Lima V, Bernardi F, Yamada D, Cassão V, Barbosa-Junior F, Félix T, et al. Enhancing Rare Disease Management and Care: Proposal of an Evidence-Based Digital Platform for Second Opinions. Procedia Comput Sci, vol. 256, Elsevier B.V.; 2025, p. 1277–84. [CrossRef]

- Rifino N, Bersano A, Padovani A, Conti GM, Cavallini A, Colombo L, et al. Virtual hospital and artificial intelligence: a first step towards the application of an innovative health system for the care of rare cerebrovascular diseases. Neurological Sciences 2024;45:2087–95. [CrossRef]

- Vuocolo B, Sierra R, Brooks D, Holder C, Urbanski L, Rodriguez K, et al. Project GIVE: using a virtual genetics service platform to reduce health inequities and improve access to genomic care in an underserved region of Texas. J Neurodev Disord 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Mena R, Mendoza E, Gomez Peña M, Valencia CA, Ullah E, Hufnagel RB, et al. An international telemedicine program for diagnosis of genetic disorders: Partnership of pediatrician and geneticist. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2020;184:996–1008. [CrossRef]

- Douzgou S, Pollalis YA, Vozikis A, Patrinos GP, Clayton-Smith J. Collaborative Crowdsourcing for the Diagnosis of Rare Genetic Syndromes: The DYSCERNE Experience. Public Health Genomics 2016;19:19–24. [CrossRef]

- Douzgou S, Clayton-Smith J, Gardner S, Day R, Griffiths P, Strong K. Dysmorphology at a distance: Results of a web-based diagnostic service. European Journal of Human Genetics 2014;22:327–32. [CrossRef]

- Mönig I, Steenvoorden D, de Graaf JP, Ahmed SF, Taruscio D, Beun JG, et al. CPMS–improving patient care in Europe via virtual case discussions. Endocrine 2021;71:549–54. [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:573–6. [CrossRef]

- Mandel JC, Kreda DA, Mandl KD, Kohane IS, Ramoni RB. SMART on FHIR: A standards-based, interoperable apps platform for electronic health records. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2016;23:899–908. [CrossRef]

- Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health 2019;7. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Monitoring and Evaluating Digital Health Interventions A practical guide to conducting research and assessment. 2016.

- Sharma AE, Lisker S, Fields JD, Aulakh V, Figoni K, Jones ME, et al. Language-Specific Challenges and Solutions for Equitable Telemedicine Implementation in the Primary Care Safety Net During COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med 2023;38:3123–33. [CrossRef]

- Shin TM, Dodenhoff KA, Pardy M, Wehner AS, Rafla S, McDowell LD, et al. Providing Equitable Care for Patients With Non-English Language Preference in Telemedicine: Training on Working With Interpreters in Telehealth. MedEdPORTAL 2023;19:11367. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).