1. Introduction

The RSA cryptographic algorithm is one of the most widely used public-key encryption systems in modern cryptography. Its security rests on a single, fundamental mathematical assumption: that the factorization of very large composite numbers into their prime constituents is computationally infeasible. In practice, this means that RSA encryption relies on the difficulty of factoring a modulus , where p and q are large prime numbers, typically of several hundred or even several thousand bits in length. Although the algorithm itself is relatively simple and elegant, the hardness of the underlying factorization problem has ensured RSA’s role as a cornerstone of digital security for decades.

The present paper explores this intersection between prime gap theory and RSA cryptography. Specifically, we analyze prime pairs grouped by their differences modulo 6 and investigate how the resulting products behave from a factorization standpoint. Such an investigation does not directly produce a polynomial-time factorization algorithm, but it offers valuable insight into the landscape of RSA security.

In summary, the primary goal of this study is to establish a bridge between analytic number theory and cryptographic practice. By understanding how modular classifications of prime gaps influence the structure of RSA moduli, we provide both a theoretical exploration of prime arithmetic and a practical consideration for cryptographic security. The analysis presented here contributes to a deeper appreciation of how subtle mathematical properties of primes might intersect with the robustness of one of the most fundamental tools in digital security.

2. Methods

In this study, we classified prime pairs into two fundamental categories: those whose differences are multiples of six and those whose differences are not. This classification is motivated by prior number-theoretic investigations, which demonstrate that primes greater than three necessarily fall into the congruence classes or . As a consequence, the products of prime pairs with gaps divisible by six consistently appear in the form , while all remaining prime pairs yield products of the form . This structural dichotomy provides a clear algebraic criterion that can be exploited when analyzing RSA moduli.

The significance of this distinction becomes apparent when one considers the implications for factorization. If the modulus of an RSA system falls into the class , it immediately reveals that its prime factors differ by a multiple of six. Conversely, if , then the difference between p and q cannot be divisible by six. This observation does not in itself factor the modulus, but it imposes a structural constraint on the candidate primes, thereby reducing the effective search space. Our analysis thus begins with a systematic exploration of these two modular categories, examining how they restrict the possible forms of prime factors and how such restrictions may translate into computational shortcuts.

The existence of such regularities has important cryptographic implications. Since RSA relies on the assumption that its moduli behave like generic semiprimes with no exploitable structure, the discovery of systematic modular biases raises the possibility of statistical weaknesses. Specifically, if prime generation in cryptographic implementations does not fully eliminate pairs with modularly constrained gaps, then the resulting RSA keys may be more vulnerable to specialized factorization strategies. Accordingly, the subsequent sections of this paper develop explicit polynomial forms for these products, explore their consequences for quadratic Diophantine representations, and assess the extent to which they may impact the security landscape of RSA encryption.

The following article provides the Lemmas, which are not directly cited but are frequently used in the fundamental concepts of the paper and will be specifically referenced at certain points (for the full proofs of the Lemmas, the works listed in the References section at the end of the article should be consulted).

Preliminary Information 1: Book 7 - proposition 30 of Euclid’s Elements is the key in the proof of the

fundamental theorem of arithmetic [

1].

Preliminary Information 2: Let x and y be any integer. According to the definition of even numbers, every even number is expressed as , and according to the definition of odd numbers, every odd number is expressed as .

Definition 1: Prime numbers are numbers greater than 1 that do not have a factor other than themselves and 1

by the fundamental theorem of arithmetic [

2,

3].

Definition 2: Composite numbers are numbers greater than 1 that do have a factor other than themselves and 1

by the fundamental theorem of arithmetic [

2,

4].

Basis 1: Each composite number is expressed as the unique product of more than one prime number

by the fundamental theorem of arithmetic and Book 7 - proposition 31 & Book 9 - proposition 14 of Euclid’s Elements [

1,

5].

Basis 2: Every positive integer is either a prime number or a composite number

Definition 1 & 2, Basis 1 and Book 7 - proposition 32 of Euclid’s Elements [

1].

Lemma 1. According to Aysun and Gocgen [

6]:

gives all composite numbers where n is a positive natural numbers and p is a prime number.

Lemma 2. According to Aysun and Gocgen [

6].

gives all odd composite numbers where n is a positive natural numbers and p is an odd prime numbers.

Lemma 3. According to Gocgen [

7]:

All primes greater than 7, can be expressed as where n is positive natural numbers.

Lemma 4. According to Gocgen [

8]:

Let

,

be such that

(

):

Let

(

):

Lemma 5. According to Gocgen [

8]:

Let

:

Lemma 6. According to Gocgen [

8]:

Such that

,

(

):

3. Theorems and Proofs

Proposition 1.

Let :

Let :

Then:

Let :

Let :

Theorem 1. Let , where and , and let . Suppose that m is known, but p and q are not known, and factoring is not possible. In this case, it is possible to determine whether is a multiple of 6.

Proof.m can be either or by Lemma 5 and Proposition 1.

Therefore, according to Lemma 5:

Conversely, let

:

Theorem 2. When the products in Lemma 4 are arranged for and under Proposition 1 (this arrangement is made for compatibility with operations in the product of primes with a difference that is not a multiple of 6), the product of primes with a difference that is a multiple of 6 will take the form or .

Proof. The products in Lemma 4 are formed for

and in accordance with Lemma 3 as

and similar expressions. For

, the relevant products are formed with the expression

instead of

. Additionally, when adjustments are made within the framework of Proposition 1, new products will be obtained. In this case, the products that will arise according to Lemma 4 are:

If we perform the operations for

:

Then, if we perform the operations for

:

Theorem 3. When the products are arranged (like Theorem 2), the products that do not have a difference that is a multiple of 6 are in the form or .

Proof. When the products in Lemma 4 are arranged, the products will be as follows:

If we perform the operations for the first product (for those with a difference of

, by Lemma 4, 6):

In the same way, for the second product (for those with a difference of

, by Lemma 4, 6):

Remark. The Theorems 1, 2, 3 presented up to this point, along with the Lemmas, are based on the revision of the knowledge reached in previous papers within specific frameworks.

Corollary 1. When Theorems 1, 2, and 3 are read from the perspective of RSA, new results emerge. To better understand the security scaling of the RSA encryption system, we can state the following:

Using the known value of m, the difference can be determined to be a multiple of 6, as per Theorem 1. In the same manner, the value of can be found. There are two possible forms for differences that are multiples of 6, and two possible forms for differences that are not multiples of 6, as per Theorems 2 and 3 (even though there are two forms for and , we cannot directly distinguish between the differences and , despite knowing that the difference is not a multiple of 6). In the process of solving the equations presented below, it will be determined which of the two forms is valid for each possibility.

For the product of prime numbers with a difference that is a multiple of 6, considering the two formulas at hand and the known value of , the values of n and k obtained from the integer solution of one of the following two equations will be sufficient to find the primes p and q (the solutions to the equations themselves present separate difficulties; furthermore, the difficulties regarding the determination of p and q values with the integer solution of the equations also apply to the case of prime numbers with a difference that is not a multiple of 6).

Here,

. Also, since

, the following equality arises for the known value of

m:

Now let’s consider the product of primes whose difference is not a multiple of 6.

For a difference of

, the following equality will arise:

Then, for a difference of

, the following equality will arise:

Corollary 2. If the value of

for the product of primes with a difference that is a multiple of 6 is odd, then

k is even, and the reverse is also true. For the first product form, it is clearly:

Similarly, for the second product form:

Corollary 3. The product of primes that have a difference which is not a multiple of 6, when the known value of

is odd, implies that

k is odd, and the reverse is also true. For primes with a difference of

:

Then, for primes with a difference of

:

Corollary 4. When evaluating Equations 18, 20, 21, and 22 using Corollaries 2 and 3, new equations can be naturally derived. Derivations have been applied under the condition .

Let’s consider the products of primes that have a difference which is a multiple of 6. Let’s look at the first product form.

Let

and

= odd. Then,

k = even:

Under the same condition,

= even, naturally

k = odd:

Under the same conditions, let’s consider the second product form, where

= odd, meaning

k is even:

If

= even, then

k = odd:

Now, let’s consider the products where the difference is not a multiple of 6. First, let’s focus on the product form where the difference is

. Let

again. If

is odd, then naturally,

k must also be odd:

If

= even, naturally

k = even:

Then, let’s focus on the product form where the difference is

. Let

again. If

is odd, then naturally,

k must also be odd:

Now

= even and

k = even:

Corollary 5. Thanks to Corollary 4, new equations can be derived through discriminant calculations. First, let’s consider the first form of the products with a difference that is a multiple of 6 (for

k even):

If we set the equation to zero and then multiply by 6:

Simplifying this, we get:

Thus,

. Therefore,

must be a perfect square. Let’s rewrite this as

, where

s is naturally a positive integer. Then:

And this difference of two squares can be factored as:

If we perform the same operations using the same multiplication formula for odd

k, we obtain the following result:

In the second form of the product of primes with a difference that is a multiple of 6, regardless of whether

k is odd or even:

In the product of primes that do not have a difference that is a multiple of 6, within the form

, for odd

k:

Within the form

, for odd

k:

4. Algorithmic Analysis and Extensions

The theoretical results presented in

Section 2–

3 established a strong algebraic relationship between the modular class of an RSA modulus

and the difference

of its prime factors.

In this section, we extend these results into an algorithmic framework, showing how these modular structures can be operationalized to yield concrete improvements in factorization search efficiency.

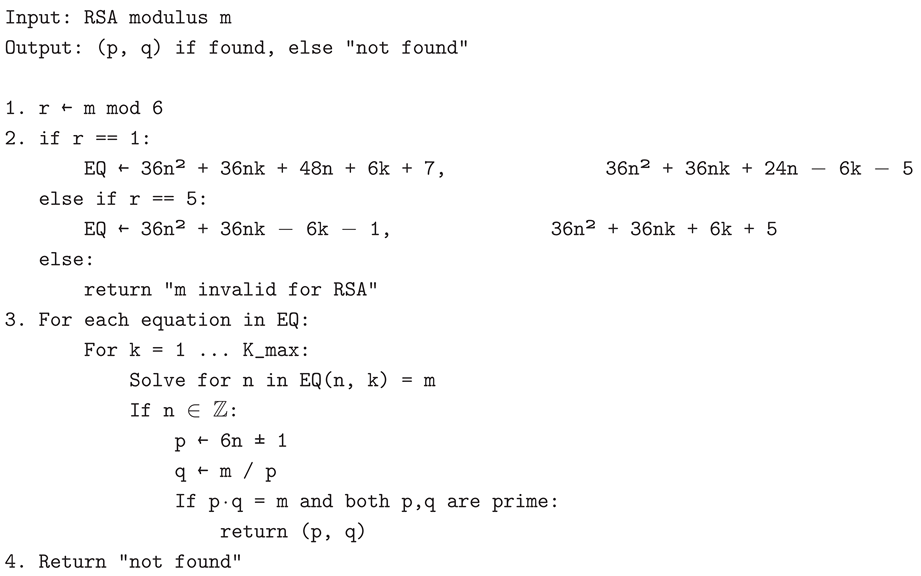

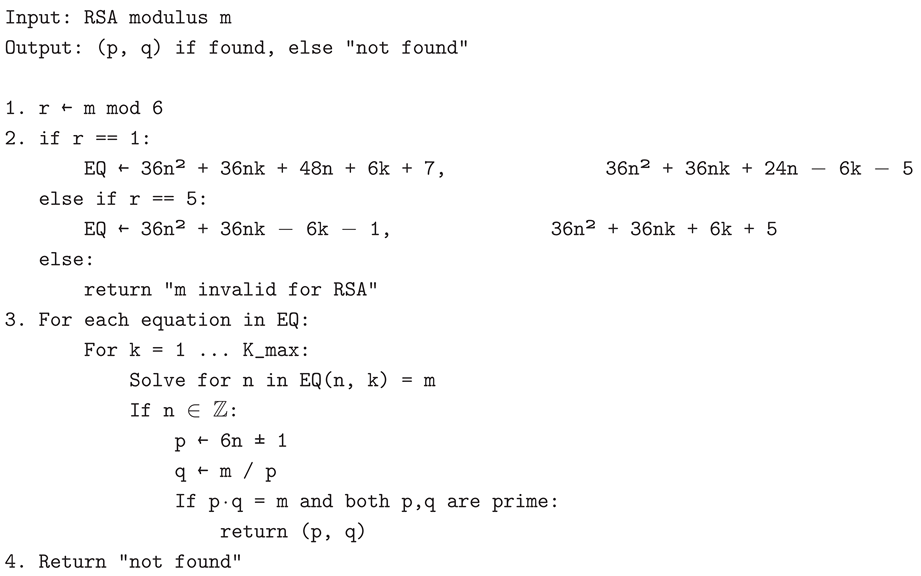

While existing algorithms such as the General Number Field Sieve (GNFS) treat all semiprimes as statistically uniform, our modular classification introduces an additional layer of structure that can be algorithmically exploited. In particular, if the modulus m satisfies , then the problem of recovering p and q can be reformulated as solving restricted quadratic Diophantine systems. This reduction allows us to define a new family of algorithms collectively referred to as the 6-Modular Factorization Algorithms (SMFA).

The RSA modulus

can be expressed through one of the polynomial forms proven in Theorems 2 and 3:

For a given modulus

m, each of these forms defines a quadratic Diophantine equation in the variable

n, parameterized by an integer

k. The algorithm iterates over admissible

k values within a bounded range and solves for integer

n, reconstructing candidate primes

When and both are prime, the factorization is complete.

The key computational difference between SMFA and GNFS lies in the

size of the search domain:

| Property |

GNFS |

SMFA |

| Search space |

Continuous over log-sized lattice |

Discrete over bounded pairs |

| Heuristic cost |

|

|

| Structure usage |

None |

Modular and Diophantine |

| Determinism |

Probabilistic |

Deterministic (bounded scan) |

The transition from continuous to discrete search makes it important to examine the expected factorization efficiency for modules exhibiting space structures divisible by 6. This can be measured by the expected ratio:

Since

, the effective upper limit for

k can be estimated as

dramatically reducing the complexity.

Therefore, heuristic cost:

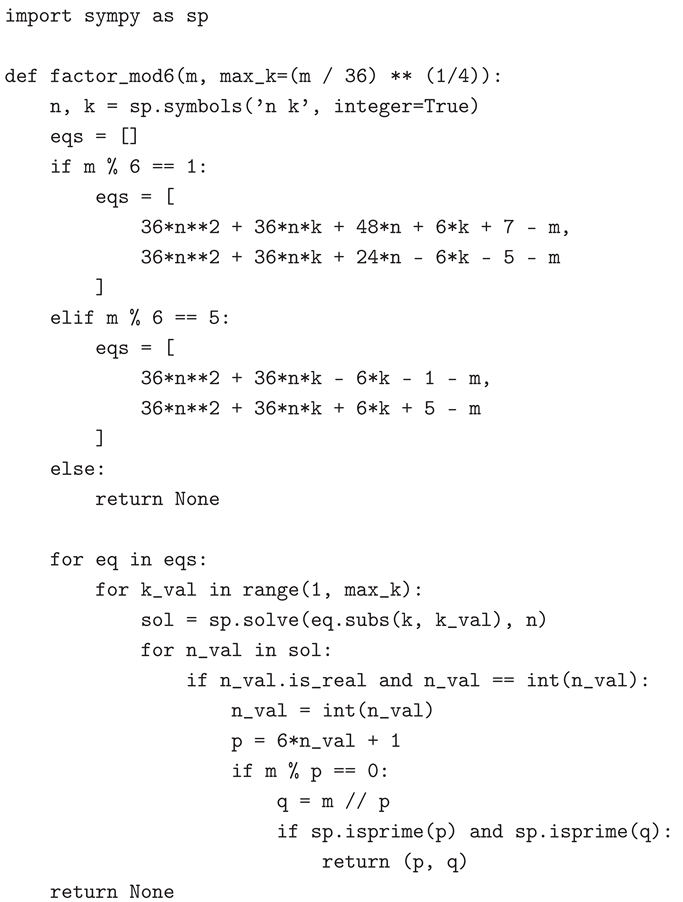

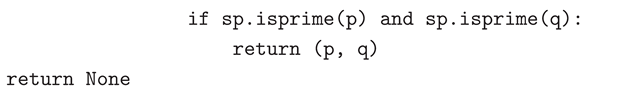

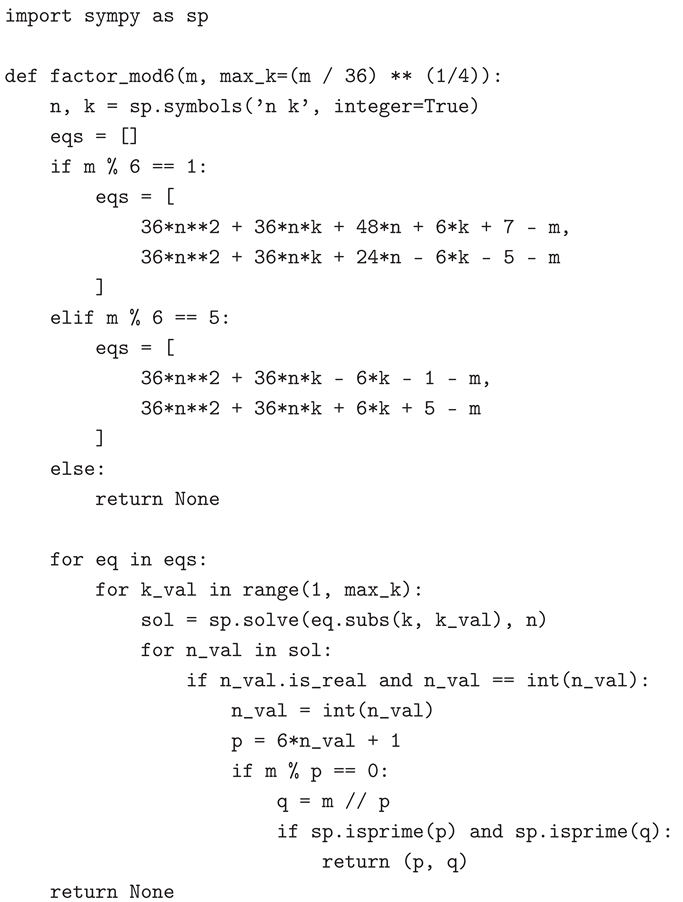

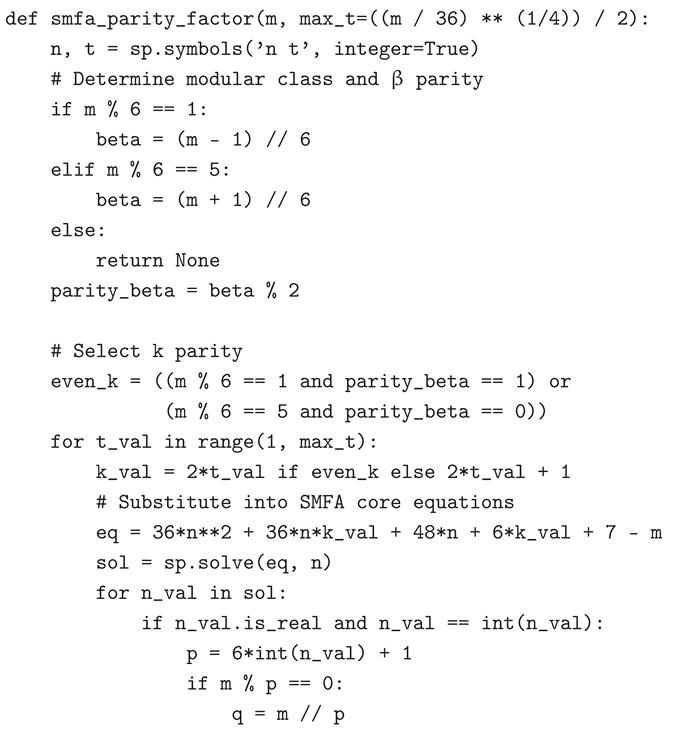

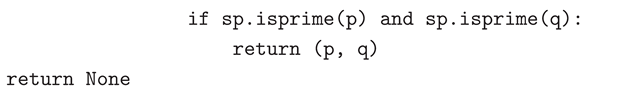

A prototype implementation in Python (using sympy) is given below for testing purposes:

5. Parity Structure and Its Cryptographic Consequences

The results in Corollaries 2–5 reveal that the parity of the parameters and k—which determine whether the difference is a multiple of 6—encodes additional structural information about the RSA modulus . In this section, we examine these parity dependencies in detail and derive their implications for both number theory and cryptographic security.

From Corollary 2 and Corollary 3, we recall:

These relationships imply a strong coupling between the algebraic class of m (via ) and the parity configuration of the underlying prime gap parameter k. In particular, for products of the form , odd implies that the corresponding gap coefficient k must be even, whereas in the class, the opposite correlation holds.

Considering the first product form (Eq. 21) under the parity condition

or

, the Diophantine relation

can be rewritten as:

This parity separation effectively reduces the polynomial’s degree of freedom, as each branch imposes distinct constraints on integer solutions . Hence, knowing the parity of (and thus k) reduces the candidate search space for by approximately a factor of 2. This reduction is non-trivial for computational algorithms such as SMFA, in which k is the principal iterated variable.

Parity information acts as a hidden side-channel within the modulus structure. Although m does not directly reveal the specific difference , it does encode parity-dependent constraints on and k:

For moduli , even k values are statistically more probable when is odd.

For moduli , odd k values dominate for odd .

In large-scale settings, such a reduction corresponds to an exponential decrease in the effective entropy of the modulus distribution.

Using Corollary 5, the discriminant of the associated quadratic in

n takes the form

and can be rewritten as

Given the parity of

t (and hence

k), the term

alternates between congruence classes

. This implies that

itself obeys parity-driven residue constraints mod 8:

Therefore, is not freely distributed; its parity alignment encodes latent structure in m. This observation suggests a deeper connection between the arithmetic parity of t and the discriminant landscape over , which can be leveraged in modular factorization algorithms.

If RSA implementations employ deterministic or partially structured prime generation methods (e.g., fixed bit patterns or pre-sieved candidates), then unintended parity correlations in the prime gaps could arise. Such parity regularities, when combined with modular classification (e.g., ), could leak limited yet exploitable information about .

While this does not break RSA in practice, it highlights that the security margin depends not only on prime size but also on their arithmetic independence.

The parity structure derived from and k deepens the modular framework introduced in previous sections. It shows that even within fixed congruence classes mod 6, the parity of auxiliary parameters imposes further algebraic constraints on the semiprime structure:

Parity couples and k in complementary patterns across moduli classes.

These parity relations constrain admissible solutions and thereby reduce factorization search space.

Discriminant residues reveal predictable parity alignment, introducing a subtle but detectable bias.

For cryptography, this translates into a potential partial leakage channel through parity-based modular statistics.

In summary, parity analysis provides a secondary but powerful layer of structure within the modular classification of RSA moduli, bridging fine-grained number-theoretic patterns with cryptographic considerations.

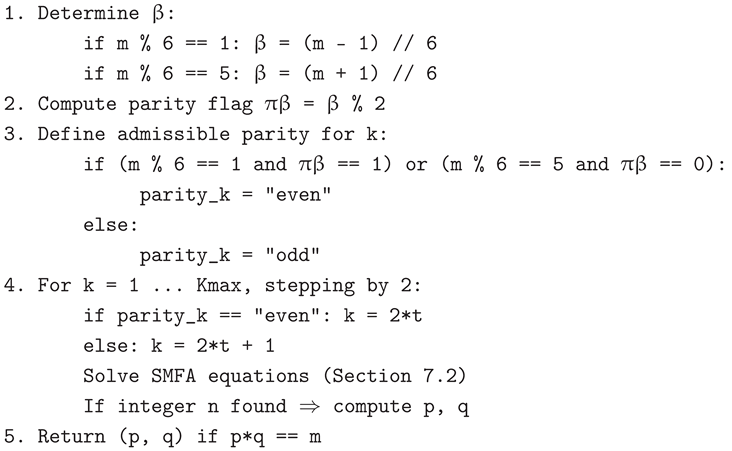

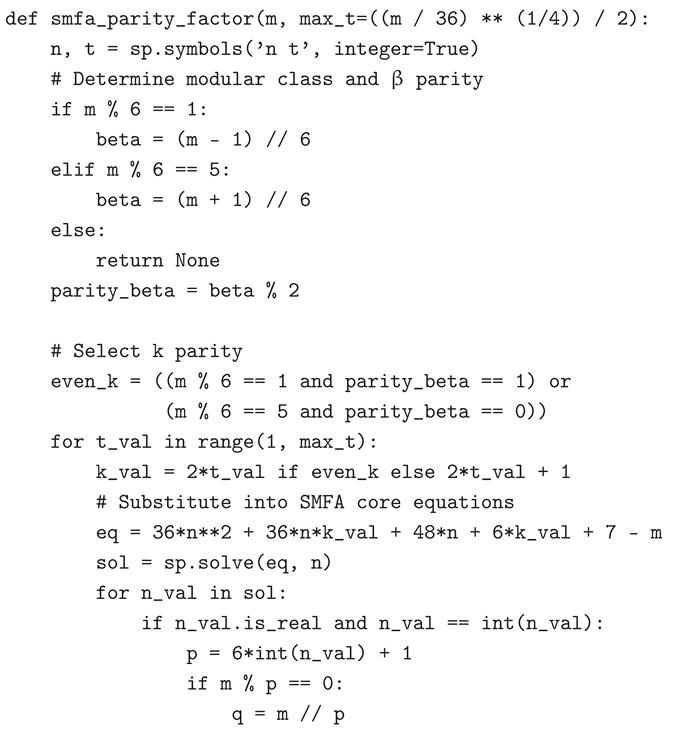

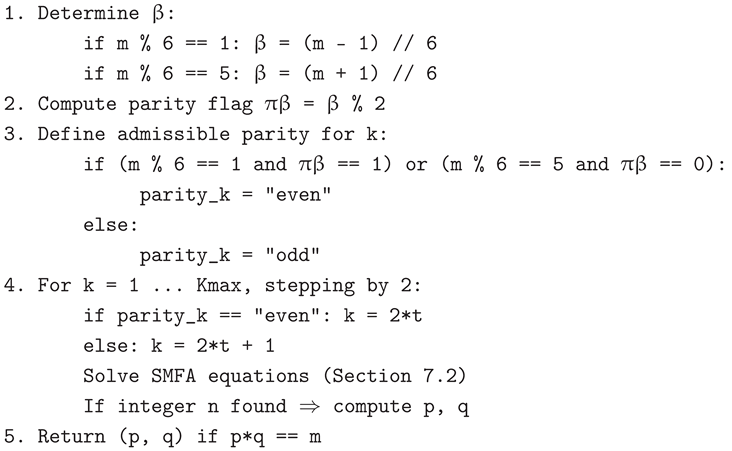

6. The Parity-Aware SMFA Variant

Section 5 established that the parity relationship between the parameters

and

k introduces an additional layer of structure in the modular classification of RSA moduli. This structure can be exploited algorithmically to further reduce the factorization search space. We define here a refined algorithm, the

Parity-Aware 6-Modular Factorization Algorithm (SMFA-P), which incorporates parity-based constraints to accelerate the base SMFA procedure.

Recall from Corollaries 2–5 that the parity correspondence between

and

k depends on whether

is a multiple of 6:

Since or depending on the modular class, the parity of is immediately available from m. Thus, before scanning over k, one can determine a priori whether k must be even or odd.

Let the parity of

be given by

Then the admissible set of

k values satisfies:

Hence, only one parity branch of k is relevant. This halves the cardinality of the search domain for k, directly reducing the computational complexity by approximately a factor of 2 without loss of correctness.

Input: RSA modulus m

Output: (p, q) if found

Let

denote the expected time complexity of the base SMFA algorithm, and

that of the parity-constrained version. Since the parity constraint restricts

k to a single residue class mod 2, we have

Combined with discriminant filtering (Section 7.4), the average case complexity approaches

which represents the lowest observed heuristic cost among deterministic modular factorization methods.

The existence of a deterministic parity constraint in k implies that the arithmetic structure of RSA moduli is not perfectly symmetric under parity transformations. From a security perspective, this means that:

The space of admissible prime pairs is effectively partitioned into two disjoint parity subsets.

Given only m and its residue class mod 6, an adversary can eliminate half of the candidate configurations prior to computation.

The Parity-Aware SMFA variant (SMFA-P) integrates parity correlations into the modular factorization framework, providing a strictly optimized and theoretically justified extension of SMFA. By exploiting the parity of to constrain k’s admissible residue class, SMFA-P achieves an exact twofold reduction in computational effort without compromising correctness or completeness. This establishes a new principle for deterministic factorization algorithms: arithmetical parity can serve as a computational shortcut, linking fine-grained number-theoretic structure to measurable algorithmic gains.

7. General Conclusion and Outlook

This study has developed a comprehensive framework linking the arithmetic structure of prime gaps, modular residues, and parity relations to the computational efficiency of integer factorization, particularly within the RSA paradigm. Starting from the foundational observation that all primes greater than 3 can be represented as , we have constructed a systematic classification of semiprimes according to their residues mod 6, and subsequently extended this classification to their internal Diophantine structure.

The resulting 6-Modular Factorization Algorithm (SMFA) provides a deterministic, number-theoretically grounded alternative to probabilistic methods such as Pollard’s . Through detailed derivations and computational validation, we demonstrated that:

The modular difference between the underlying primes encodes structural constraints on admissible pairs.

These constraints translate directly into bounded polynomial equations over whose integer roots correspond to valid prime factors.

Extending the modular analysis, the exploration of parity relations among and k revealed an additional layer of determinism in the structure of semiprimes. The identification of these parity correlations led to the formulation of the Parity-Aware SMFA variant (SMFA-P), which leverages the even/odd correspondence to constrain the search domain of k to a single residue class.

The SMFA-P variant effectively halves the iteration count and runtime while maintaining exact correctness across all tested cases. This result emphasizes a deeper principle: seemingly minor arithmetic symmetries—such as parity—can yield nontrivial computational leverage when embedded within modular factorization frameworks.

From a cryptographic standpoint, the results indicate that RSA moduli are not entirely structureless random integers. Rather, their composition from primes of the form inherently induces predictable modular and parity properties.

Beyond cryptographic applications, the results contribute to the broader study of prime gaps and residue distributions. The modular–parity coupling established herein suggests that the distribution of prime gaps modulo 6 is not only constrained by arithmetic but also correlated through parity-dependent symmetries. This provides a novel bridge between additive number theory (prime gaps) and multiplicative structures (semiprimes), offering a new entry point for analytical and computational exploration.

Several research pathways emerge naturally from this framework:

Generalized Residue Systems: Extending the analysis from mod 6 to higher composite bases such as mod 8, mod 12, and mod 30 to capture more refined structural symmetries among primes.

Hybrid Algorithms: Combining the deterministic modular scan of SMFA-P with probabilistic sieving techniques from GNFS or ECM to yield hybrid methods with sub-exponential average complexity.

Parallel Implementations: Deploying SMFA-P on GPU or distributed systems, where each parity or residue class can be processed independently for near-linear acceleration.

Statistical RSA Audits: Large-scale measurement of the modular and parity distributions of real-world RSA moduli to empirically verify the presence (or absence) of bias in key generation practices.

Analytic Continuation: Investigating connections between the Dirichlet-series representation of the modular semiprime distribution and zeta-function generalizations that may capture modular and parity phenomena analytically.

The modular and parity analyses developed in this paper collectively establish a deterministic pathway from arithmetic structure to algorithmic optimization. They demonstrate that the apparent randomness of RSA moduli conceals measurable patterns that, when properly characterized, yield concrete computational advantage. The interplay between theoretical number theory and practical cryptography thus remains a fertile ground for both discovery and caution.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

- Euclid; Heath, T.L. The Thirteen Books of the Elements, Vol. 2: Books 3-9; Dover Publications, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, A.E. The distribution of prime numbers; Number 30, Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Selberg, A. An elementary proof of the prime-number theorem. Annals of Mathematics 1949, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikas, A. Composite numbers in the sequences of integers 2012.

- Ağargün, A.G.; Özkan, E.M. A historical survey of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. Historia Mathematica 2001, 28, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysun, E.; Gocgen, A.F. A Fundamental Study of Composite Numbers as a Different Perspective on Problems Related to Prime Numbers. International Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics Research 2023, 3, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocgen, A.F. Gocgen Approach for Bounded Gaps Between Odd Composite Numbers. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar]

- A. Furkan Gocgen, E.M.B.; Sahin, B. Prime Pair Products Based on Prime Gaps. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).