Submitted:

06 October 2025

Posted:

07 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

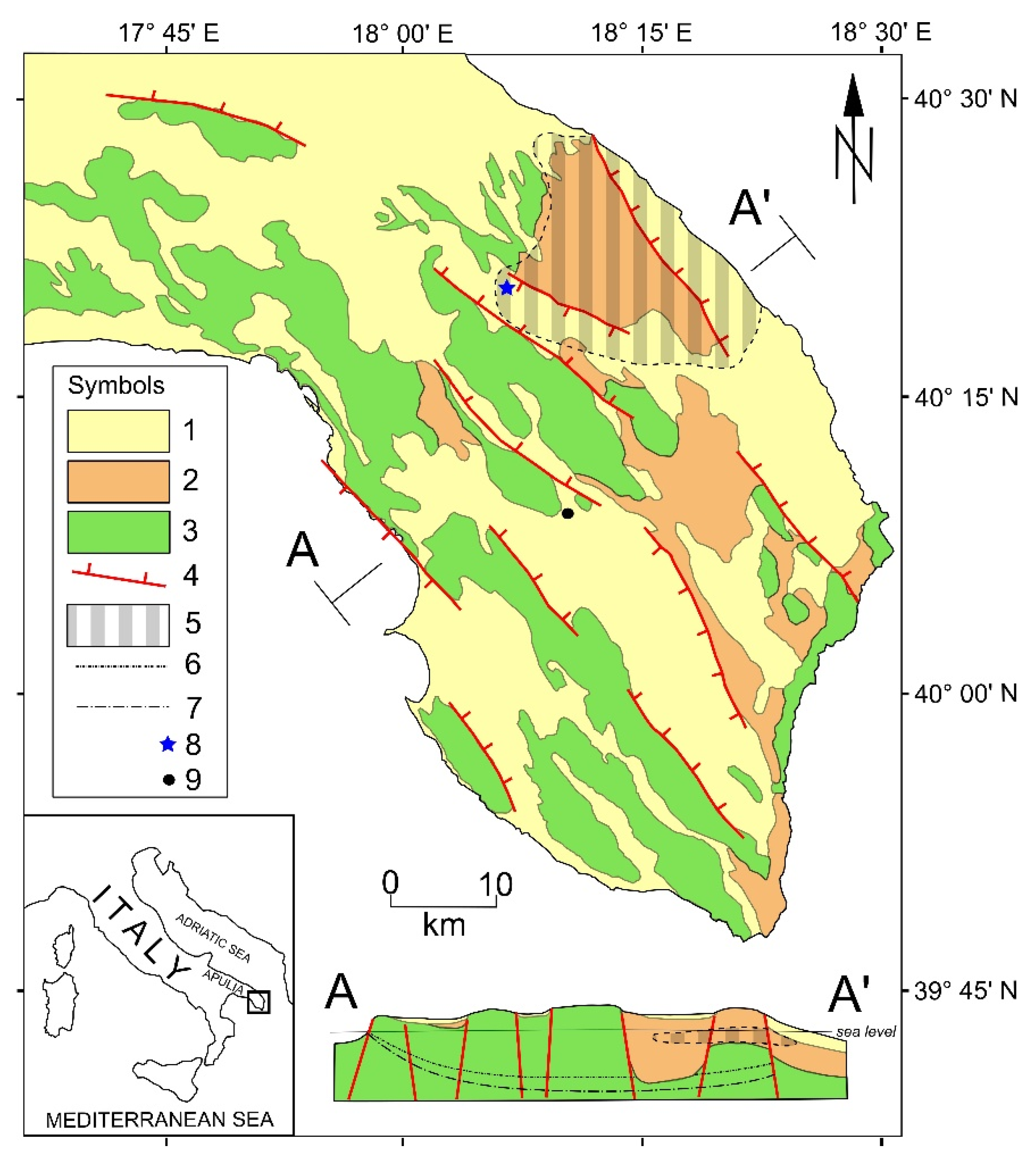

2. Study Area and Site Description

2.1. Hydrogeological and Climate Setting

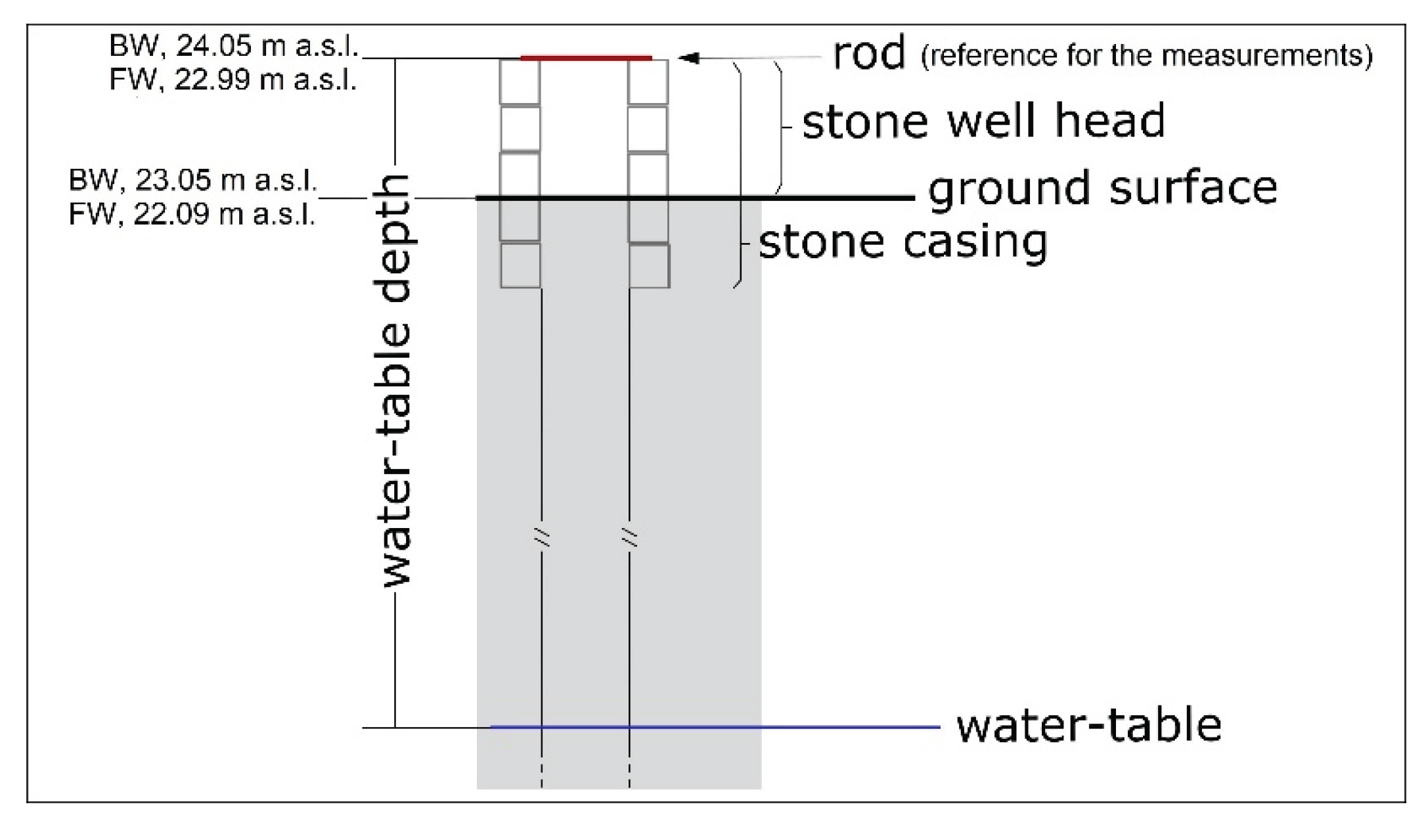

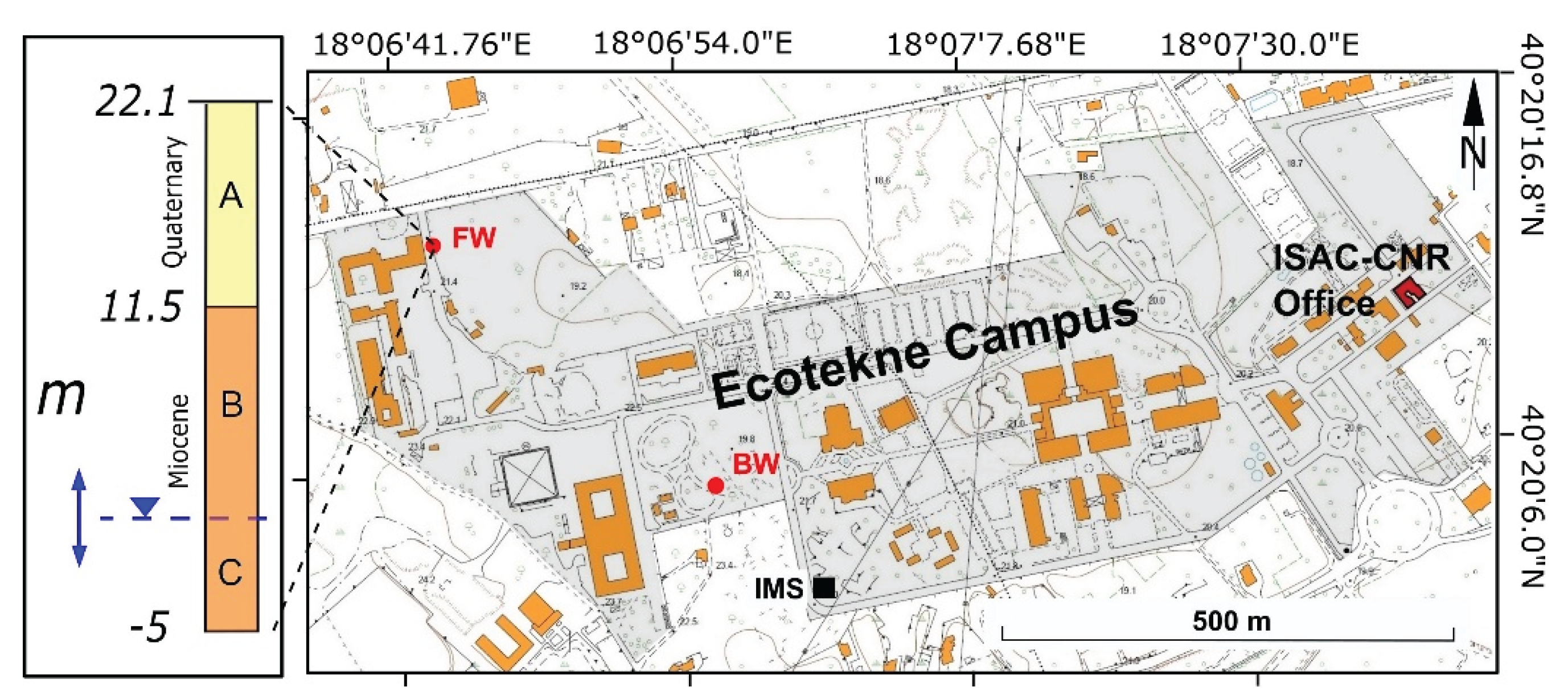

2.2. The Measurement Site

3. Method

4. Results

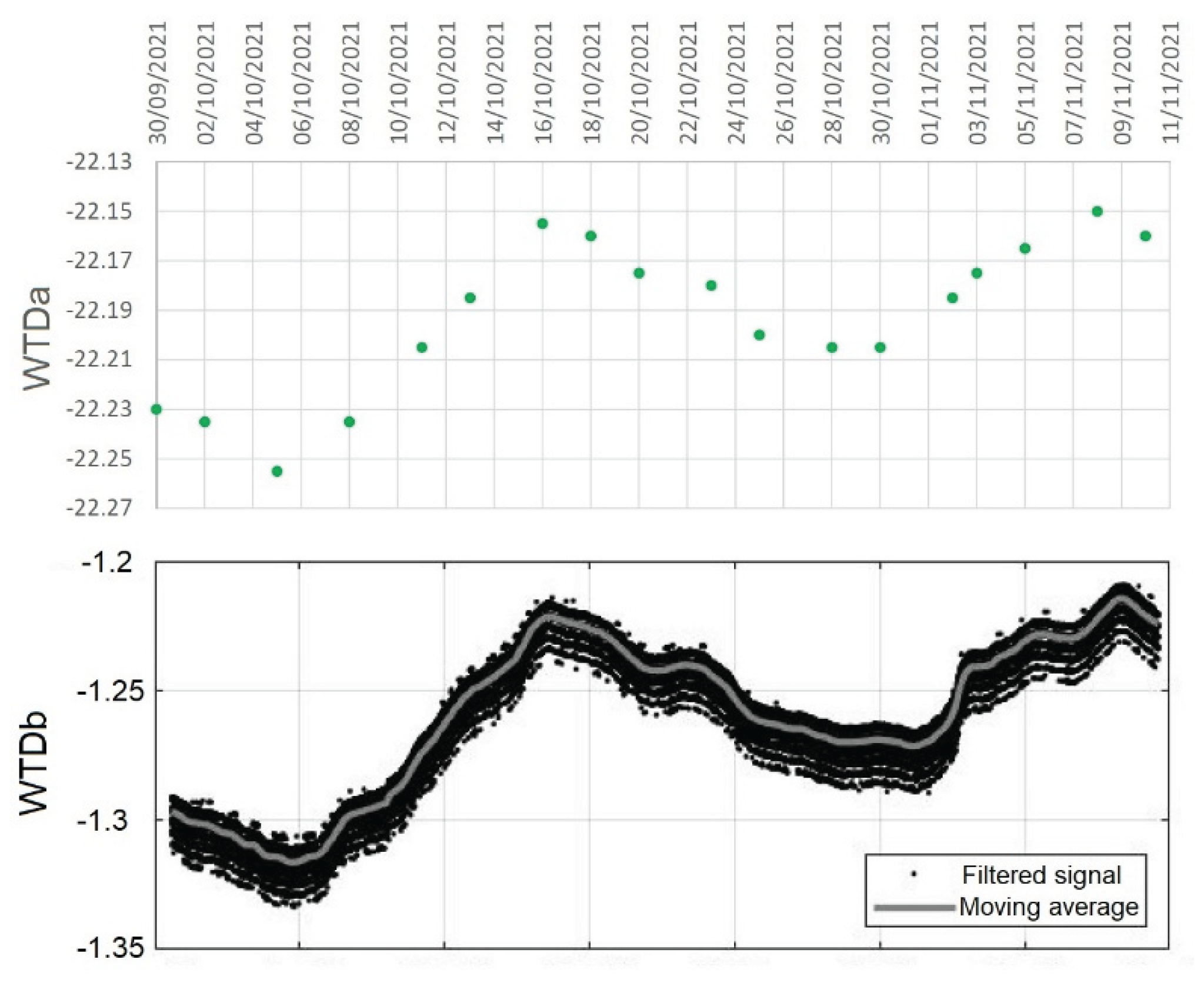

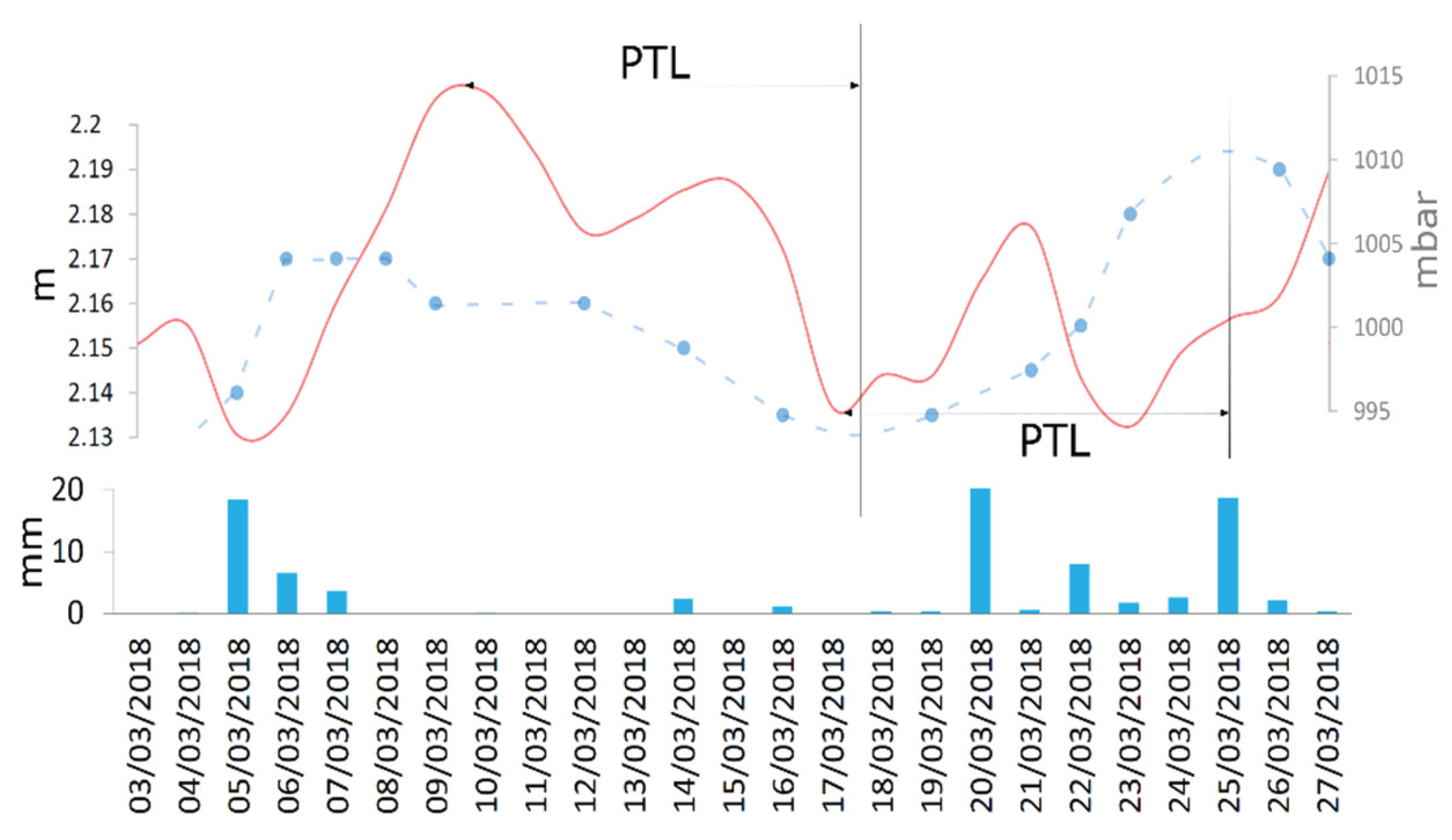

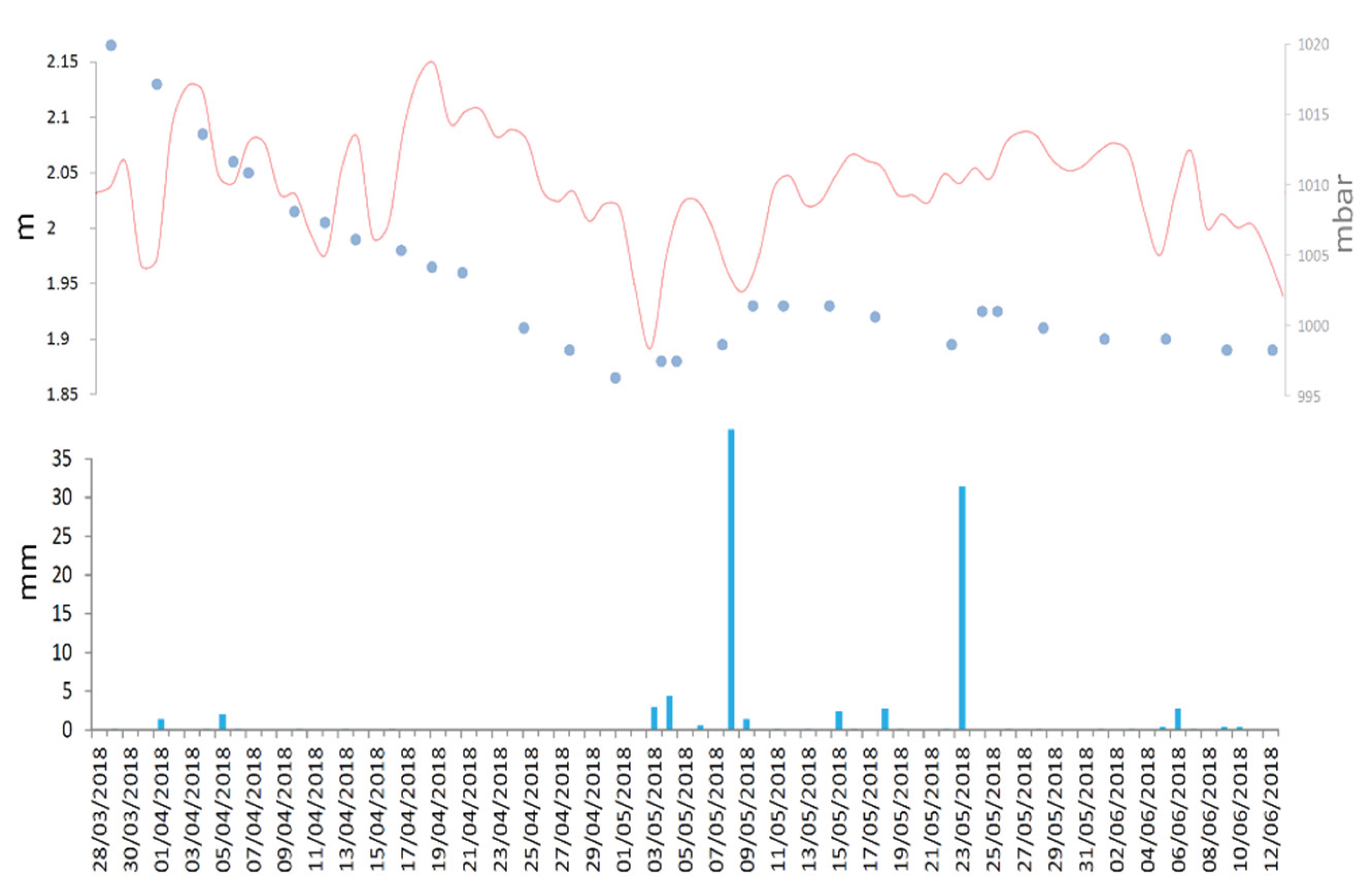

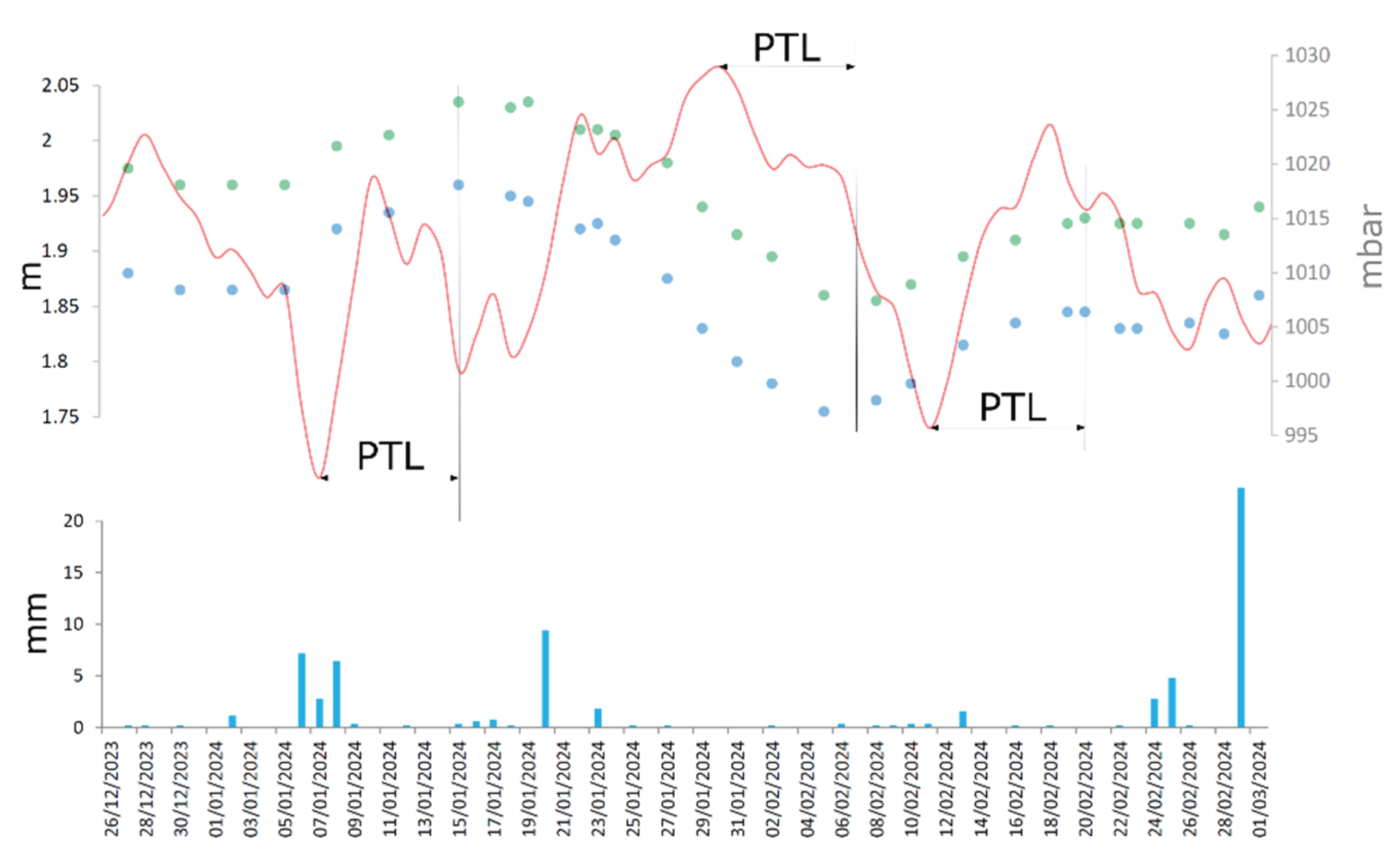

4.1. First Observations and Hydrograph Interpretations

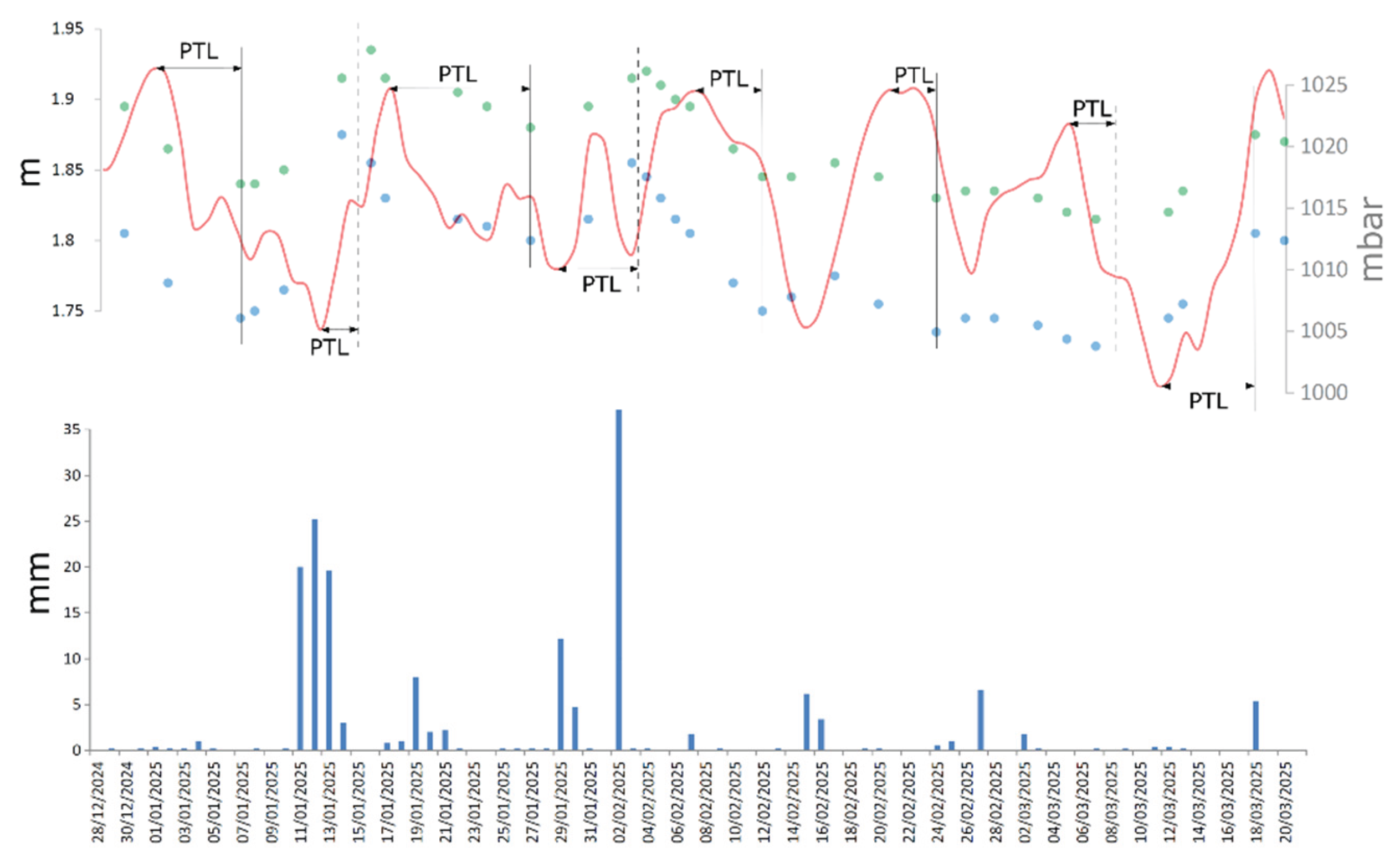

4.2. Atmospheric Pressure Change Effect

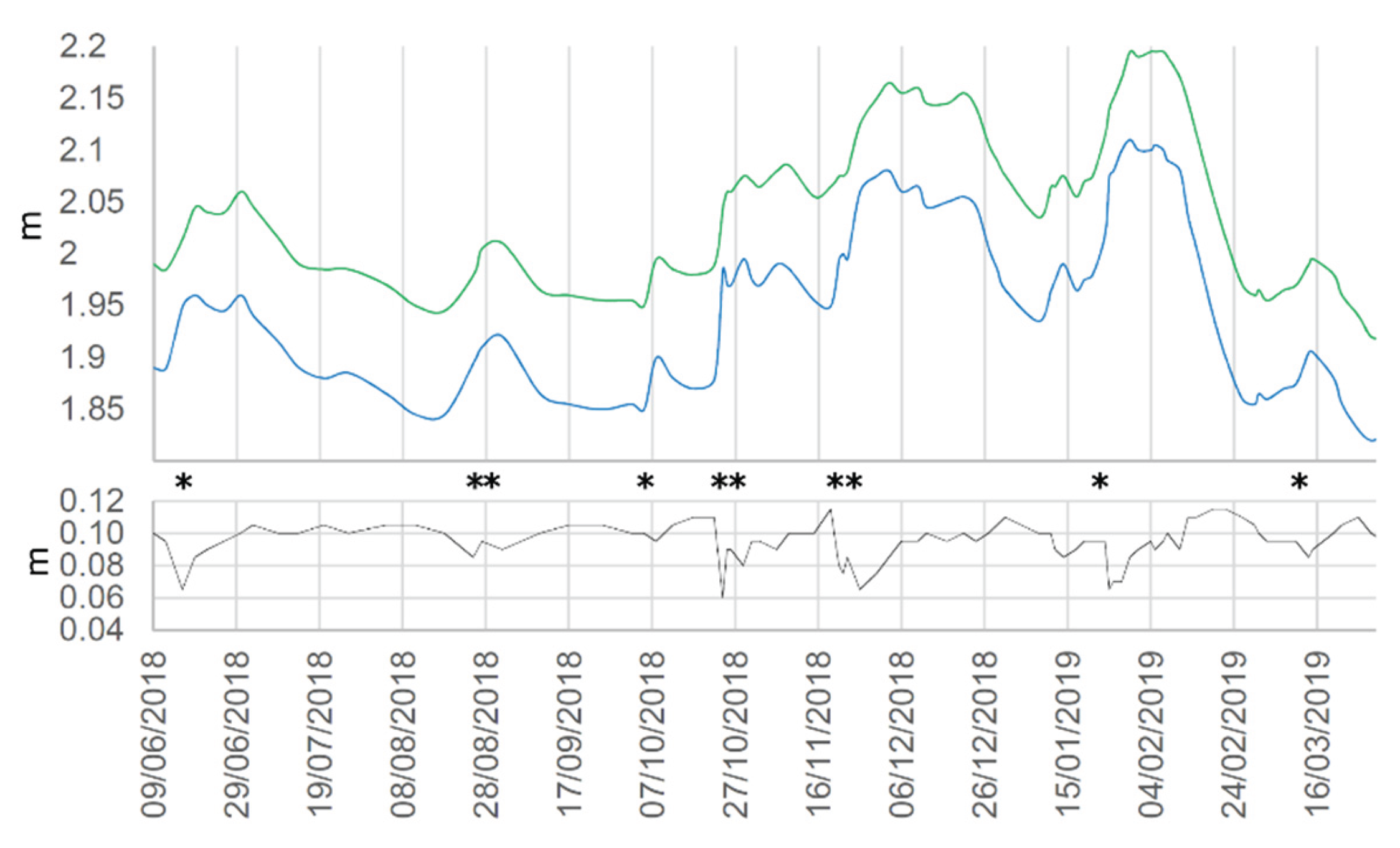

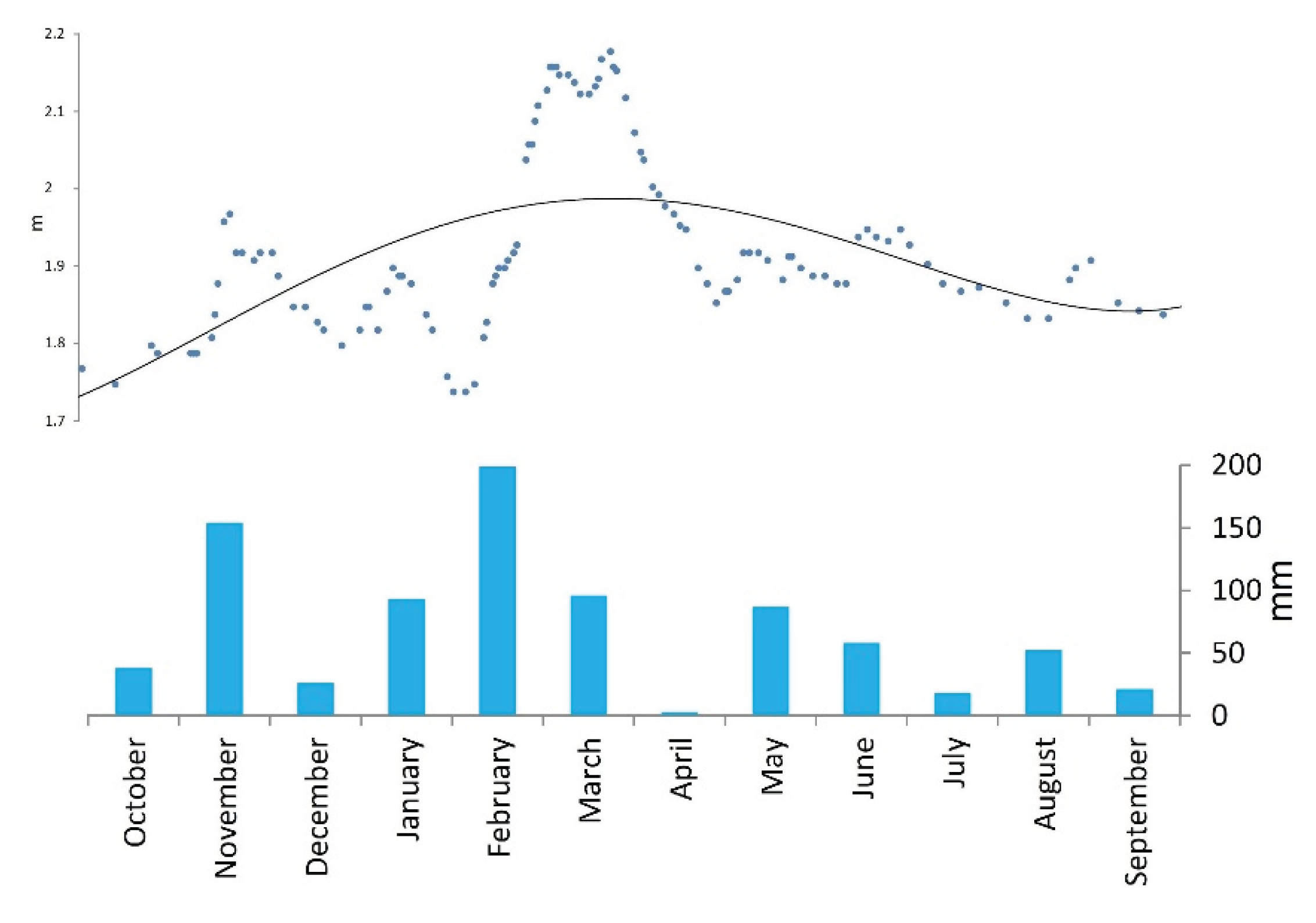

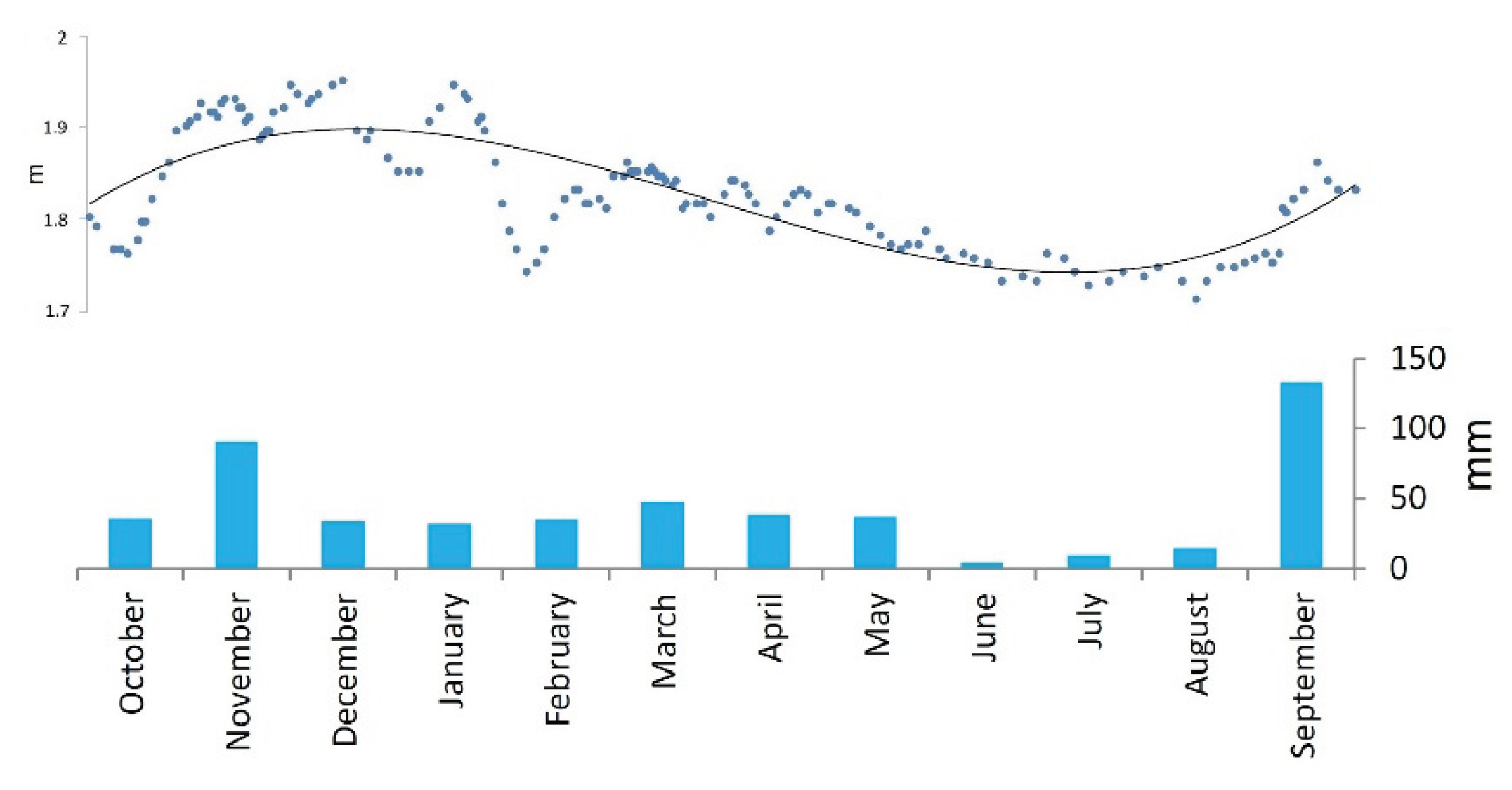

4.3. Seasonal Groundwater Fluctuations

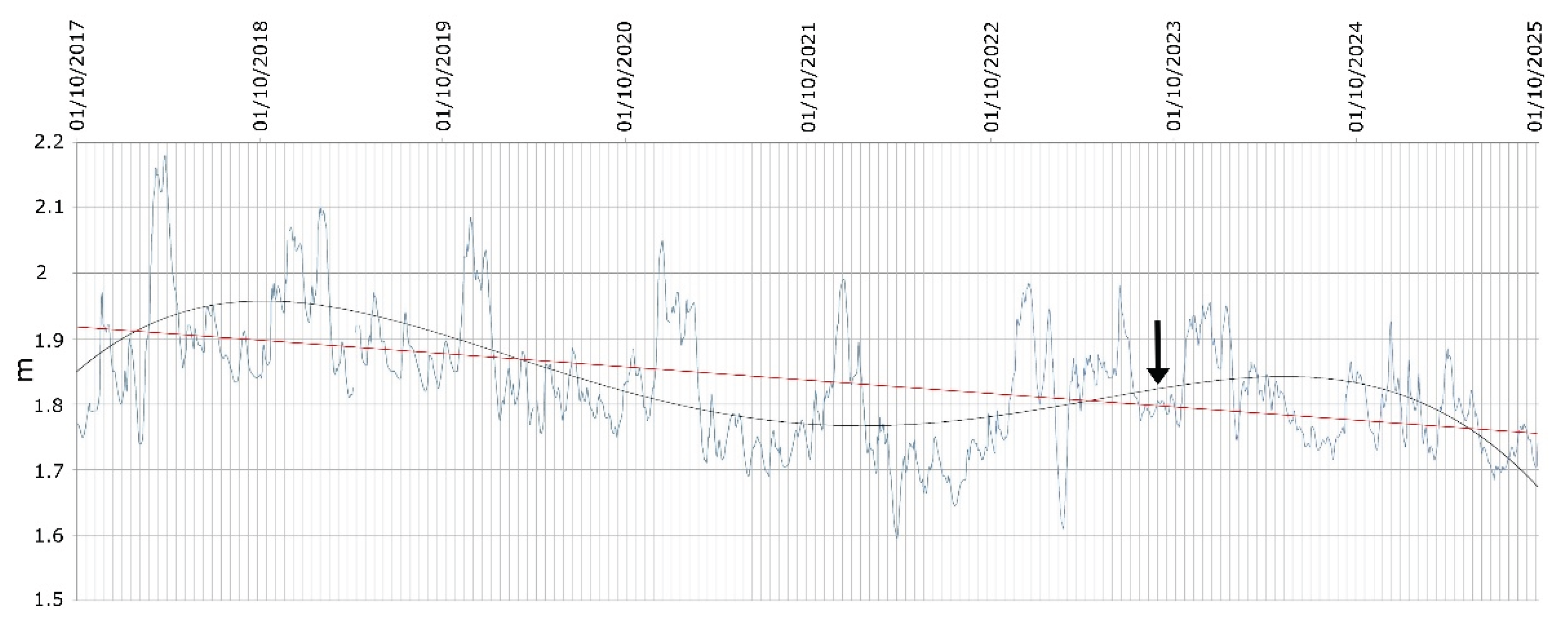

4.4. Multi-Annual Trend of Groundwater Level

5. Discussion

5.1. Weather Forcings over Different Time Scales

5.2. Relevance of the Site in the Regional Context

5.3. Future Research Goals

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASL | Average Summer Level |

| AGLC | Annual Groundwater Level Change |

| APV | Annual Precipitation Variation |

| CA | Cretaceous Aquifer |

| GR | Groundwater Recharge |

| HRSL | Highest Rainy Season Level |

| LDSL | Lowest Dry Season Level |

| MACES | Miocene Aquifer of the Central-Eastern Salento |

| WTF | Water Table Fluctuation |

Appendix A. Site Characteristics

Appendix B. Phenomena affecting WTFs

Appendix C. Hypotheses on the Similarity of Hydrographs

References

- Healy, R.W.; Cook, P.G. Using groundwater levels to estimate recharge. Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favreau, G.; Cappelaere, B.; Massuel, S.; Leblanc, M.; Boucher, M.; Boulain, N.; Leduc, C. Land clearing, climate variability, and water resources increase in semiarid southwest Niger: A review. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45, W00A16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Garcia, C.; Morán-Tejeda, E. Groundwater level responses to precipitation variability in Mediterranean insular aquifers. J. Hydrol. 2017, 552, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeze, R.A., Cherry, J.A. Groundwater. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA, 1979; 604 pp.

- Leduc, C.; Bromley, J.; Schroeter, P. Water table fluctuation and recharge in semi-arid climate: some results of the HAPEX-Sahel hydrodynamic survey (Niger). J. Hydrol. 1997, 188–189, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touhami, I.; Andreu, J.M.; Chirino, E.; Sanchez, J.R.; Mourahir, H.; Pulido-Bosch, A.; Martinez-Santos, P.; Bellot, J. Recharge estimation of a small karstic aquifer in a semiarid Mediterranean region (southeastern Spian) using a hydrological model. Hydrol. Process. 2013, 27, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazola, A. , Shamsudduha, M., French, J., MacDonald, A.M., Abiye, T., Goni, I.B., Taylor, R.G. High-resolution long-term average groundwater recharge in Africa estimated using random forest regression and residual interpolation. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 2949–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Ries, J. Lange, S. Schmidt, H. Puhlmann, and M. Sauter. Recharge estimation and soil moisture dynamics in a Mediterranean, semi-arid karst region. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 19, 1439–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Berthelin, M. Rinderer, B. Andreo, A. Baker, D. Kilian, G. Leonhardt, A. Lotz, K. Lichtenwoehrer, M. Mudarra, I.Y. Padilla, Pantoja Agreda, F.; Rosolem, R.; Vale, A.; Hartmann, A. A soil moisture monitoring network to characterize karstic recharge and evapotranspiration at five representative sites across the globe. Geosci. Instrum. Method. Data Syst. 2020, 9, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Alfio, M.R.; Balacco, G.; Delle Rose, M.; Fidelibus, C.; Martano, P. A hydrometeorological study of groundwater level changes during the covid-19 lockdown year (Salento peninsula, Italy). Sustainability 2022, 14, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Rose, M.; Martano, P. Datasets of groundwater level and surface water budget in a central Mediterranean site (21 June 2017–1 October 2022). Data 2023, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadolini, T.; Tulipano, L. The evolution of fresh-water/salt water equilibrium in connection with withdrawals from the coastal carbonate and karst aquifer of the salentine peninsula (southern Italy). Geol. Jaharb. 1981, 29, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tulipano, L. Temperature logs interpretation for the identification of preferential flow pathway in the coastal carbonatic and karstic aquifer of the Salento peninsula (Southern Italy). In Proceedings of the 21 Congress International Association Hydrogeologists, Guilin, China, 10–15 October 1988; volume 2; pp. 956–961. [Google Scholar]

- Delle Rose, M. Sedimentological features of the Plio-Quaternary aquifers of Salento (Puglia). In Memorie Descrittive delle Carta Geologica d’Italia; S.E.L.C.A., Florence, Italy, 2007; volume 76, pp. 137–145.

- Delle Rose, M.; Fidelibus, C.; Martano, P. Assessment of specific yield in karstified fractured rock through the water-budget method. Geosciences 2018, 8, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotecchia, V. Sviluppi della teoria di Ghyben ed Herzberg nello studio idrogeologico dell’alimentazione e dell’impiego delle falde acquifere, con riferimento a quella profonda delle Murge e del Salento. Geotecnica 1958, 6, 301–318. (In Italian) [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese, I.; Uricchio, V.; Vurro, M. A GIS tool for hydrogeological water balance evaluation on a regional scale in semi-arid environments. Comput. Geosci. 2005, 31, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelibus, M.D.; Tulipano, L.; D’Amelio, P. Convective thermal field reconstruction by ordinary kriging in karstic aquifers (Puglia, Italy): geostatistical analysis of anisotropy. In Advances in Research in Karst Media. Environmental Earth Sciences; Andreo, B., Carrasco, F., Durán, J., LaMoreaux, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Giudici, M.; Margiotta, S.; Mazzone, F.; Negri, S.; Vassena, C. Modelling hydrostratigraphy and groundwater flow of a fractured and karst aquifer in a Mediterranean basin (Salento peninsula, southeastern Italy). Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 67, 1891–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotecchia, V.; Grassi, D.; Polemio, V. Carbonate aquifers in Apulia and seawater intrusion. Giornale di Geologia Applicata 2005, 1, 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Apollonio, C.; Delle Rose, M.; Fidelibus, C.; Orlanducci, L.; Spasiano, D. Water management problems in a karst flood-prone endorheic basin. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, G.; Muschitiello, C.; Ferrara, R.M.; Verdiani, G.; Acutis, M. Modelling the groundwater level by water balance: a case study of a Mediterranean karst aquifer of Apulia region (Italy). Ital J. Agrometeorol. 2018, 23, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Delle Rose, M.; Martano, P. Infiltration and Short-Time Recharge in Deep Karst Aquifer of the Salento Peninsula (Southern Italy): An Observational Study. Water 2018, 10, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, G.; Ruggiero, L.; Zuanni, F. Aspetti meteorologici e climatici della Puglia. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on “Clima, Ambiente e Territorio nel Mezzogiorno”, Taormina, Italy, 11–12 December 1989; CNR: Roma, Italy, 1991; pp. 43–73. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- Martano, P.; Elefante, C.; Grasso, F. Ten years water and energy surface balance from the CNR-ISAC micrometeorological station in Salento peninsula (southern Italy). Adv. Sci. Res. 2015, 12, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F.; Lionello, P. Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2008, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladisa, G.; Todorovic, M.; Trisorio Liuzzi, G. A GIS-based approach for desertification risk assessment in Apulia region, SE Italy. Phys. Chem. Earth 2012, 49, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oria, M.; Tanda, M.G.; Todaro, V. Assessment of Local Climate Change: Historical Trends and RCM Multi-Model Projections Over the Salento Area (Italy). Water 2018, 10, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elferchichi, A.; Giorgio, G.A.; Lamaddalena, N.; Ragosta, M.; Telesca, V. Variability of Temperature and Its Impact on Reference Evapotranspiration: The Test Case of the Apulia Region (Southern Italy). Sustainability 2017, 9, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, F.; Pennetta, L. Geomorphological map of the Salento peninsula. J. Maps 2007, 3, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanazzi, A.; Gentile, F.; Polemio, M. Modelling and management of a Mediterranean karstic coastal aquifer under the effects of seawater intrusion and climate change. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olin, M. Estimation of base level for an aquifer from recession rates of groundwater levels. Hydrogeol. J. 1995, 3, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadolini, T.; Calo, G.; Spizzico, M.; Tinelli, R. Caratterizzazione idrogeologica dei terreni post-cretacei presenti nell’area di S. In Cesario di Lecce (Puglia). In Proceedings of the V Congresso Internazionale sulle Acque Sotterranee, Taormina, Italy, 17–21 November 1985; p. 11 (In Italian). (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, A.; Massari, F.; Davaud, E.; Ghibaudo, G. Pliocene–Pleistocene sequences bounded by subaerial unconformities within foramol ramp calcarenites and mixed deposits (Salento, SE Italy). Sediment. Geol. 2004, 166, 89–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusa, Y. The fluctuation of the level of the water table due to barometric change. In Special Contributions of the Geophysical Institute; Kyoto University: Kyoto, Japan, 1969; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, E.P. Barometric fluctuations in wells tapping deep unconfined aquifers. Water Resour. Res. 1979, 15, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spane, F.A. Considering barometric pressure in groundwater flow investigations. Water Resour. Res. 2002, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, J.D. A material theory of induction. Philos. Sci. 2003, 70, 647–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeijn, J.W. Inductive logic and statistics. In Handbook of the History of Logic, volume 10; Gabbay, D.M., Hartmann, S., Woods, J., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 625–650. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A.A. Inductive reasoning in the context of discovery: Analogy as an experimental stratagem in the history and philosophy of science. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 2018, 69, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.J.; Knobbe, S.; Reboulet, E.C.; Whittemore, D.O.; Wilson, B.B.; Bohling, G.C. Water well hydrographs: an underutilized resource for characterizing subsurface conditions. Groundwater 2021, 59, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedd, K.M.; Misstear, B.D.R.; Coxon, C.; Daly, D.; Hunter Williams, N.H. Hydrogeological insights from groundwater level hydrographs in SE Ireland. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2012, 45, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotchoni, D.O.V.; Vouillamoz, J.M.; Lawson, F.M.A.; Adjomayi, P.; Boukari, M.; Taylor, R.G. Relationships between rainfall and groundwater recharge in seasonally humid Benin: a comparative analysis of long-term hydrographs in sedimentary and crystalline aquifers. Hydrogeol. J. 2019, 27, 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Grasby, S.E.; Osadetz, K.G. Relation between climate variability and groundwater levels in the upper carbonate aquifer, southern Manitoba, Canada. J. Hydrol. 2004, 290, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.J.E.; Lawrence, D.S.L.; Price, M. Analysis of water-level response to rainfall and implications for recharge pathways in the Chalk aquifer, SE England. J. Hydrol. 2006, 330, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Gupta, A.; Ray, R.K.; Tewari, D. Aquifer response to recharge–discharge phenomenon: inference from well hydrographs for genetic classification. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, J.F.; Olimpo, J.C. Estimation of recharge rates to the sand and gravel aquifer using environmental tritium, Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. U.S. Geological Survey water-supply paper, 2297; U.S. Geological Survey: Denver, Colorado, USA, 1986; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Barreiras, N.; Ribeiro, L. Estimating groundwater recharge uncertainty for a carbonate aquifer in a semi-arid region using the Kessler’s method. J. Arid Env. 2019, 165, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, B.; Parker, A:, Sharma, A. ; Sharma, R.; Krishan, G.; Kumar S.; Le Corre, K.; Campo Moreno, P.; Singh, J. Estimation of groundwater recharge in semiarid regions under variable land use and rainfall conditions: A case study of Rajasthan, India. PLOS Water 2023, 2, e0000061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A.; Goldscheider, N.; Wagener, T.; Lange, J.; Weiler, M. Karst water resources in a changing world: Review of hydrological modeling approaches. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 218–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellman, P.; Breithaupt, C.; Bremner, P.; Gulley, J.; Jenson, J.; Lander, M. Analyzing recharge dynamics and storage in a thick, karstic vadose zone. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2021WR031704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, T.C.; Crawford, L.A. Identifying and removing barometric pressure effects in confined and unconfined aquifers. Ground Water 1997, 35, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Rojstaczer. Determination of fluid flow properties from the response of water levels in wells to atmospheric loading. Water Resour. Res. 1988, 24, 1927–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojstaczer, S.; Riley, F.C. Response of the water level in a well to earth tides and atmospheric loading under unconfined conditions. Water Resour. Res. 1990, 26, 1803–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M. Barometric water-level fluctuations and their measurement using vented and non-vented pressure transducers. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2009, 42, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.M.; Tomasek, A.A. Assessment of aquifer properties, evapotranspiration, and the effects of ditching in the Stoney Brook watershed, Fond du Lac Reservation, Minnesota, 2006–9. U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2015- 5007; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, Virginia, USA, 2015; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, K.; Paul, S.; Chy, T.J.; Antipova, A. Analysis of groundwater table variability and trend using ordinary kriging: the case study of Sylhet, Bangladesh. Appl. Water Sci. 2021, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, A.; Pulido-Bosch, A. Study of hydrographs of karstic aquifers by means of correlation and cross-spectral analysis. J. Hydrol. 1995, 168, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T.J.; Western, A.W. Nonlinear time--series modeling of unconfined groundwater head. Water Resour. Res. 2014, 50, 8330–8355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Shi, Z.; Rasmussen, T.C. Time- and frequency-domain determination of aquifer hydraulic properties using water-level responses to natural perturbations: A case study of the Rongchang Well, Chongqing, southwestern China. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martano, P.; Delle Rose, M.; Donateo, A. Correlations between meteoric forcings and groundwater levels in a karst aquifer well, 2025. Preprint available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5132771 (accessed on 19/09/2025).

- Cuthbert, M.O.; Taylor, R.G.; Favreau, G.; Todd, M.C.; Shamsudduha, M.; Villholth, K.G.; MacDonald, A.M.; Scanlon, B.R.; Kotchoni, V.D.O.; Vouillamoz, J.-M.; Lawson, F.M.A.; Adjomayi, P.A.; Japhet, K.; Seddon, D.; Sorensen, J.P.R.; Ebrahim, G.Y.; Owor, M.; Nyenje, P.M.; Nazoumou, Y.; Goni, I.; Ousmane, B.I.; Tenant, S.; Ascott, M.J.; Macdonald, D.M.J.; Agyekum, W.; Koussoube, Y.; Wanke, H.; Kim, H.; Wada, Y.; Lo, M.-H.; Oki, T.; Kukuric, N. Observed controls on resilience of groundwater to climate variability in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature 2019, 572, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkeltaub, T.; Bel, G. Changes in mean evapotranspiration dominate groundwater recharge in semi-arid regions. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 4263–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfio, M.R.; Balacco, G.; Parisi, A.; Totaro, V.; Fidelibus, M.D. Drought Index as Indicator of Salinization of the Salento Aquifer (Southern Italy). Water 2020, 12, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfio, M.R.; Balacco, G.; Dragone, V.; Polemio, M. A statistical approach for describing coastal karst aquifer: the case of the Salento aquifer (southern Italy). Acque Sotterranee—Ital. J. Groundwater 2024, 13, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balacco, G.; Alfio, M.R.; Parisi, A.; Panagopoulos, A.; Fidelibus, M.D. Application of short time series analysis for the hydrodynamic characterization of a coastal karst aquifer: the Salento aquifer (Southern Italy). J. Hydroinform. 2022, 24, 420–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leins, T.; Liso, I.S.; Parise, M.; Hartmann, A. Evaluation of the predictions skills and uncertainty of a karst model using short calibration data sets at an Apulian cave (Italy). Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Rose, M.; Fidelibus, C.; Martano, P. The Recent Floods in the Asso Torrent Basin (Apulia, Italy): An Investigation to Improve the Stormwater Management. Water 2020, 12, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annali Idrologici, Protezione Civile Puglia (in Italian). Available online: https://protezionecivile.regione.puglia.it/annali-idrologici-parte-i-documenti-dal-1921-al-2021 (accessed on 19/09/2025).

- Crosbie, R.S. , Binning, P., Kalma, J.D. A time series approach to inferring groundwater recharge using the water table fluctuation method. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W01008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, R.S. , Doble, R.C., Turnadge, C., Taylor, A.R. Constraining the magnitude and uncertainty of specific yield for use in the water table fluctuation method of estimating recharge. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 7343–7361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J. , Park, E. A shallow water table fluctuation model in response to precipitation with consideration of unsaturated gravitational flow. Water Resour. Res. 2017, 53, 3505–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaumot, L.; Longuevergne, L.; Marcais, J.; Lavenant, N.; Bour, O. Frequency domain water table fluctuations reveal impacts of intense rainfall and vadose zone thickness on groundwater recharge. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 26, 5697–5720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yan, X.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. Improving the water table fluctuation method to estimate groundwater recharge below thick vadose zones. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2024, 69, 2044–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozdniakov, S.P.; Wang, P.; Lekhov, V.A. An approximate model for predicting the specific yield under periodic water table oscillations. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 6185–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Z.-L.; Lu, H.; Lv, M. A comprehensive review of specific yield in land surface and groundwater studies. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2021, 13, e2020MS002270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konikow, L.F.; Kendy, E. Groundwater depletion: A global problem. Hydrogeol. J. 2005, 13, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasechko, S.; Seybold, H.; Perrone, D.; Fan, Y.; Shamsudduha, M.; Taylor, R.G.; Fallatah, O.; Kirchner, J.W. Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally. Nature 2024, 625, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). State of the global water resources 2022 Report. WMO-No. 1333; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Sterckx, A.; Gerges, E.; Lictevout, E. The hydrological cycle is spinning out of balance. Quantitative status of groundwater; International Groundwater Resources Assessment Centre: Delft, The Netherlands, 2023; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Klove, B.; Ala-Aho, P.; Bertrand, G.; Gurdak, J.J.; Kupfersberger, H.; Kvaerner, J.; Muotka, T.; Mykra, H.; Preda, E.; Rossi, P.; Bertacchi Uvo, C.; Velasco, E.; Pulido-Velazquez, M. Climate change impacts on groundwater and dependent ecosystems. J. Hydrol. 2014, 518, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, O.V.; Crosbie, R.S.; Dawes, W.R.; Charles, S.P.; Pickett, T.; Donn, M.J. Climatic controls on diffuse groundwater recharge across Australia. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 4557–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, S.; Frances, F.; Garcia-Prats, A.; Puertes, C.; Pulido-Velazquez, M.; Sanchis-Ibor, C.; Schirmer, M.; Yang, H.; Jimenez-Martinez, J. Hydrological modeling of the effect of the transition from flood to drip irrigation on groundwater recharge using multi-objective calibration. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2021WR029677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Irvine, D.J.; Duvert, C.; Rau, G.C. Comparing Groundwater Recharge Rates Estimated Using Water Table Fluctuations and Chloride Mass Balance Across the Australian Continent, 2025. Preprint available at: https://www.authorea.com/users/887071/articles/1265119 (accessed on 19/09/2025).

- Keese, K.E.; Scanlon, B.R.; Reedy, R.C. Assessing controls on diffuse groundwater recharge using unsaturated flow modeling. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W06010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennel, J.; Parker, B. Characterizing water level responses to barometric pressure fluctuations from seconds to days. J. Hydrol. 2024, 641, 131843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, A.; Pascarella, F.; Delle Rose, M.; Cafaro, M.; Mele, G.; Madaro, F.; Tomasicchio, G.R.; Saponieri, A.; Gafa, R.M.; Delogu, D.; Francone, A.; Grassi, G.; Lay-Ekuakille, A.; Radogna, A.V.; Gatto, D.; Paglialunga, A.; Leone, E. De Bartolo, S. Multi-Scaling Aquifer Data (MUSA): un approccio integrato di gestione della falda sotterranea su scala regionale. In Proceedings of 39th Italian Conference on Hydraulics and Hydraulic Construction, Parma, Italy, 15-18 September 2024; pp. 653–656. (in Italian), (available at: https://zenodo.org/records/13584918)

- Moench, A.F. Transient Flow to a Large-Diameter Well in an Aquifer with Storative Semiconfining Layers. Water Resour. Res. 1985, 21, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkhair, K.S. Aquifer parameters determination for large diameter wells using neural network approach. J. Hydrol. 2002, 265, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smedt, F. Determination of Aquitard Storage from Pumping Tests in Leaky Aquifers. Water 2023, 15, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimene, E.B.; Lassabatere, L.; Winiarski, T.; Gourdon, R. Modeling Water Infiltration and Solute Transfer in a Heterogeneous Vadose Zone as a Function of Entering Flow Rates. J. Water Resour. Prot. 2015, 7, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Peng, B.; Wang, G. Focus on the nonlinear infiltration process in deep vadose zone. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 252, 104719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Reimann, T.; Hartmann, A. Jun Laboratory and numerical simulations of infiltration process and solute transport in karst vadose zone. J. Hydrol. 2024, 636, 131242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzo, L.; Quarta, T. Near-surface geophysical investigations inside the cloister of the historical palace Palazzo dei Celestini in Lecce, Italy. J. Geophys. Eng. 2010, 7, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Rose, M. Geological constraints on the location of industrial waste landfills in Salento karst areas (southern Italy). In Water Pollution VI, Modelling, Measuring and Prediction; Brebbia, C.A., Ed.; Witpress: Southampton, UK, 2001; pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kilmchouk, A.B. Towards defining, delimiting and classifying epikarst: Its origin, processes and variants of geomorphic evolution. Speleogenesis and Evolution of Karst Aquifers 2004, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, S.; Liedl, R.; Sauter, M. Modeling the influence of epikarst evolution on karst aquifer genesis: A time-variant recharge boundary condition for joint karst-epikarst development. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W09416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, W.H. A glossary of karst terminology; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, Columbia, USA, 1970; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, J. Point-recharge of limestone aquifers—A model from New Zealand karst. J. Hydrol. 1983, 62, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veress, 2019,, M. Shaft Lengths and Shaft Development Types in the Vadose Zone of the Bakony-Mountains (Transdanubian, Hungary. J. Soil Water Sci. 2019, 3, 54–74. [Google Scholar]

- De Bartolo, S.; Cafaro, M.; Rizzello, S.; Francone, A.; Martano, P.; Delle Rose, M.; Lauria, A.; Saponieri, A.; Tomasicchio, G.R. Water table multi-scaling aquifer data: an integrated groundwater management approach. In Proceedings of the 44th Italian Conference on Integrated River Basin Management, Rende, Italy, 22–23 June 2023; pp. 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, A.; Watlet, A.; Kaufmann, O.; Van Camp, M.; Jourde, H.; Mazzilli, N.; Rochez, G.; Deleu, R.; Quinif, Y.; Hallet, V. Assessment of groundwater recharge processes through karst vadose zone by cave percolation monitoring. Hydrol. Process. 2018, 32, 2069–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bense, V.F.; Person, M.A. Faults as conduit-barrier systems to fluid flow in siliciclastic sedimentary aquifers, Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42, W05421. [Google Scholar]

- Petrella, E.; Aquino, D.; Fiorillo, F.; Celico, F. The effect of low-permeability fault zones on groundwater flow in a compartmentalized system. Experimental evidence from a carbonate aquifer (Southern Italy), Hydrol. Process. 2015, 29, 1577–1587. [Google Scholar]

- Bense, V.F.; Gleeson, D.; Loveless, S.E.; Bour, O.; Scibek, J. Fault zone hydrogeology. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2013, 127, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

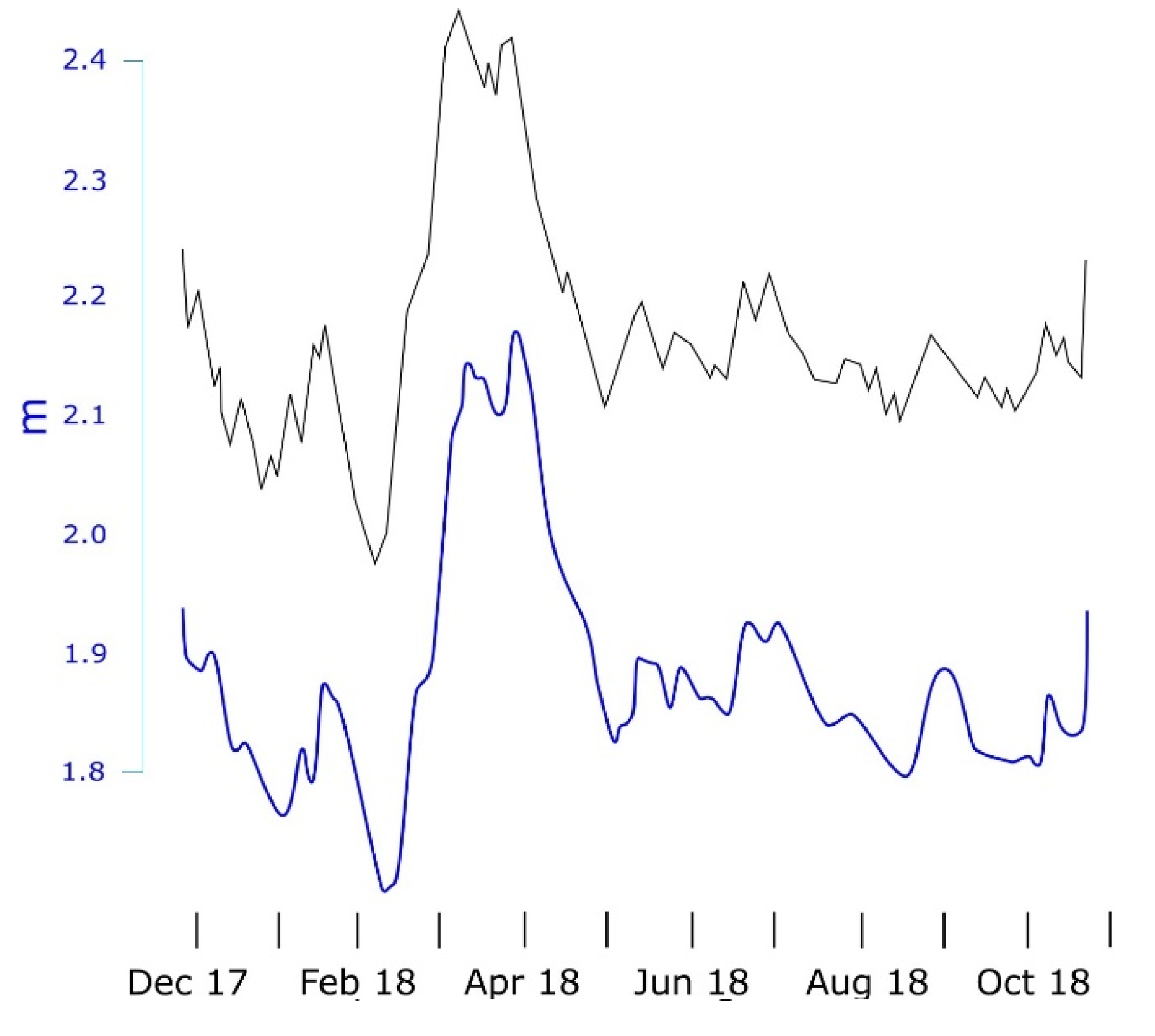

| Hydrological Year | Highest Rainy Season Level | Lowest Dry Season Level | Annual difference |

| 2017-2018 | 2.16 | 1.82 | 0.34 |

| 2018-2019 | 2.09 | 1.81 | 0.28 |

| 2019-2020 | 2.07 | 1.74 | 0.33 |

| 2020-2021 | 2.03 | 1.68 | 0.35 |

| 2021-2022 | 1.97 | 1.64 | 0.33 |

| 2022-2023 | 1.96 | 1.77 | 0.19 |

| 2023-2024 | 1.93 | 1.7 | 0.23 |

| 2024-2025 | 1.92 | 1.67 | 0.25 |

| Fiorini Well | Benessere Well | |||

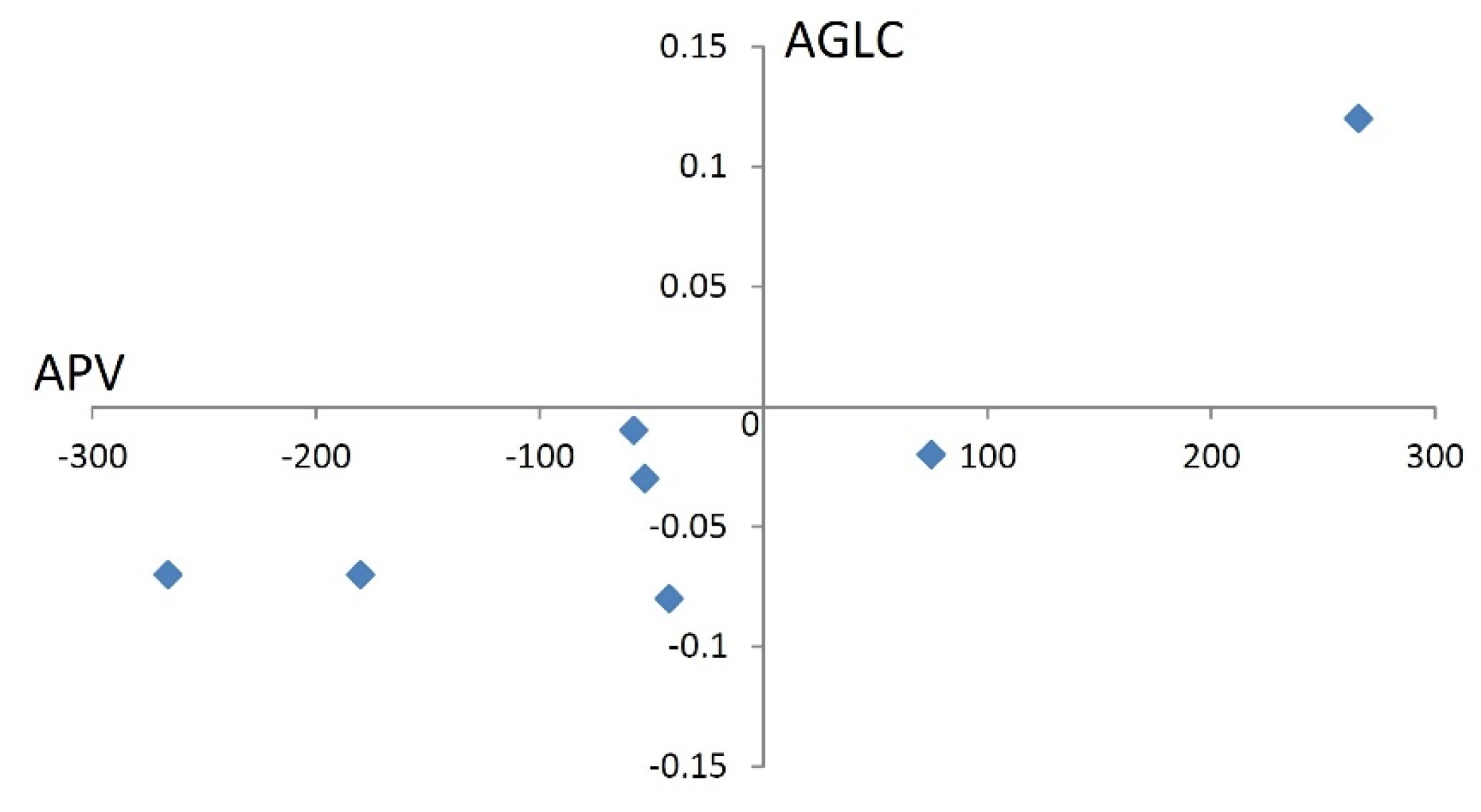

| Hydrological Year | Annual Precipitation | APV | AGLC1 | AGLC 1 |

| 2017-2018 | 845 | |||

| 2018-2019 | 787 | -58 | -0.01 | -0.01 |

| 2019-2020 | 607 | -180 | -0.07 | -0.08 |

| 2020-2021 | 565 | -42 | -0.08 | -0.07 |

| 2021-2022 | 512 | -53 | -0.03 | -0.03 |

| 2022-2023 | 778 | +266 | +0.12 | +0.12 |

| 2023-2024 | 512 | -266 | -0.07 | -0.08 |

| 2024-2025 | 587 | +75 | -0.02 | -0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).