Introduction

The standard immunosuppressive regimen most widely used in kidney transplantation is triple therapy—tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and corticosteroids [

1]. Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) are central to preventing acute rejection, but their use is associated with hypertension, nephrotoxicity, and graft fibrosis [

2]. Multiple studies have evaluated CNI replacement with alternative agents, but these strategies have not achieved comparable acute rejection rates [

3,

4]. Consequently, mTOR inhibitors have not proven suitable as complete CNI substitutes. Trials have therefore focused on reducing CNI exposure by combining CNIs with mTOR inhibitors [

4,

5]. Concomitant use has shown potential benefits, including preservation of graft function, a lower infection incidence, and possible antineoplastic effects [

6,

7,

8]. Because mTOR inhibitors impair wound healing, initiation after wound healing is considered safer [

9,

10].

In recipients undergoing early conversion from MMF to sirolimus, optimal tacrolimus and sirolimus trough targets remain uncertain. No prior study has established how to adjust and maintain these levels—individually or in combination—nor identified a consensus combined trough exposure (Csum) that balances efficacy and safety during the first post-transplant year, when rejection risk is highest.

This study aimed to define the individual therapeutic ranges of tacrolimus and sirolimus and to determine whether their combined trough level can achieve an acute rejection rate comparable to the standard triple regimen, using data from a large Korean kidney transplant cohort.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This retrospective cohort study analyzed data collected between January 2005 and December 2020 from five kidney transplant centers in South Korea that participated in a prior multicenter study [

11,

12]. Four centers with complete sirolimus trough concentration data were included in the present analysis. Adult kidney transplant recipients (≥18 years) with at least 1 year of post-transplant follow-up were eligible. Patients who received multiple kidney transplants or concomitant non-renal solid organ transplants were excluded. Based on these criteria, 9,992 recipients were initially identified. Of these, 896 patients who discontinued CNIs within the first post-transplant year and 1,069 patients who received cyclosporine-based regimens were excluded, resulting in a final cohort of 8,027 patients. The study cohort was categorized into two groups: (1) the standard group, comprising recipients who maintained tacrolimus plus MMF throughout the first post-transplant year; and (2) the early conversion group, comprising recipients converted from MMF to sirolimus within the first 3 months after transplantation who then maintained tacrolimus–sirolimus therapy for at least 1 subsequent year. To address the substantial difference in group sizes, 4:1 propensity score matching (PSM) was performed.

Definitions

Complete trough-level data were defined as at least three separate trough concentration measurements within the first post-transplant year. The combined trough concentration of tacrolimus and sirolimus (Tac–Siro Csum) was calculated by summing both drugs’ concentrations at each time point and averaging these values over the first post-transplant year. This metric was used as a surrogate of overall immunosuppressive exposure in the Tacro+Siro group. The primary endpoint was biopsy-proven acute rejection between 3 and 12 months post-transplant, i.e., after treatment-group divergence. Desensitization was defined as the administration of rituximab, plasmapheresis, or intravenous immunoglobulin before transplantation due to ABO or HLA incompatibility. BK virus positivity (BKV-positive) was defined as a quantitative plasma PCR result ≥ 3 log copies/mL.

Statistical Analysis

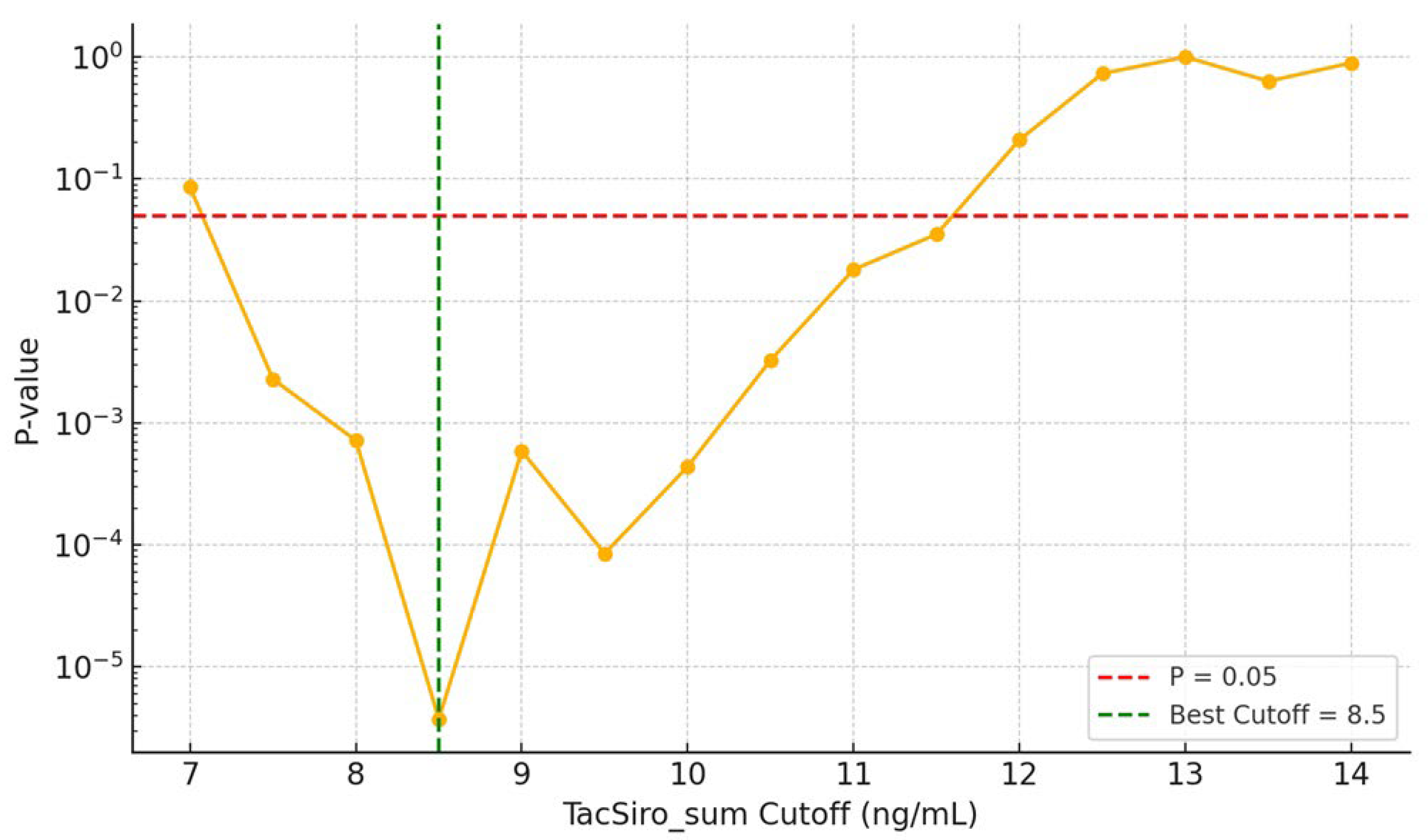

Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test. PSM used a logistic regression model including baseline covariates: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus, pre-transplant dialysis status, induction therapy, panel-reactive antibody (PRA) class I and II levels, desensitization status, donor age, ABO incompatibility, pre-transplant flow cytometric crossmatch results (B and T cells), and BK virus infection status at 3 months post-transplant. Nearest-neighbor matching without replacement was applied with a caliper of 0.2 standard deviations on the logit of the propensity score. After matching, baseline characteristics were well balanced; recipient age remained imbalanced (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.39). To determine the optimal Tac–Siro Csum cutoff, we compared rejection rates across exposure thresholds (7–14 ng/mL) and plotted the corresponding p-values on a log scale to visualize trends. Additionally, Pearson correlation was used to assess linear relationships between exposure metrics and rejection risk, with results displayed as a correlation heatmap.

All analyses were conducted in Python (v3.11.8). The pandas (v1.5.3) and numpy (v1.24.0) packages supported data preprocessing and transformation. PSM was implemented with statsmodels (v0.13.5) using a logistic regression model with nearest-neighbor matching without replacement and a 0.2-SD caliper on the logit of the propensity score. Key visualizations, including boxplots and p-value trend plots across tacrolimus–sirolimus exposure thresholds, were generated with matplotlib (v3.6.3). Pearson correlation heatmaps depicting relationships between immunosuppressant levels and rejection were produced with seaborn (v0.11.2).

Results

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

We analyzed 8,027 kidney transplantation recipients, including 7,791 (97.1%) in the standard group and 236 (2.9%) in the early-conversion group. Relative to the standard group, the early-conversion group was older (49.2 ± 12.2 vs. 45.4 ± 13.9 years; p < 0.001) and had a higher prevalence of diabetes (27.5% vs. 20.4%; p = 0.009). Induction therapy also differed (p < 0.001), with less frequent basiliximab use (63.6% vs. 77.0%) and more frequent anti-thymocyte globulin use (30.1% vs. 19.7%) in the early-conversion group. BK virus infection at 3 months was higher in the early-conversion group (16.9% vs. 8.9%; p < 0.001) (

Table 1).

After 1:4 PSM, 1,180 kidney transplant recipients were included: 944 (80.0%) in the standard group and 236 (20.0%) in the early-conversion group. All baseline variables—including sex, BMI, diabetes, desensitization, PRA levels, HLA mismatch, donor age, preemptive transplantation, ABO incompatibility, pre-transplant DSA, and 3-month BK virus infection—had SMDs < 0.1, indicating good balance, except recipient age (SMD = 0.39). Rejection between 3 and 12 months post-transplant occurred more often in the early-conversion group (7.6%) than in the standard group (2.9%), with SMD = 0.21 and p = 0.001 (

Table 2).

Risk of Acute Rejection by Combined Drug Exposure

Figure 1 shows the stepwise threshold analysis of Tac–Siro Csum in relation to acute rejection. Rejection risk remained significantly elevated below approximately 11.6 ng/mL, with the strongest risk separation at 8.5 ng/mL. Concentrations ≥11.6 ng/mL appeared safest, whereas levels <8.5 ng/mL were associated with markedly increased rejection risk.

We then assessed rejection rates by Tac–Siro Csum and CNI trough levels (

Figure 2). The highest rejection rate (14.3%) occurred with Tac–Siro Csum < 8.5 ng/mL and CNI < 5 ng/mL, whereas the lowest rate (4.6%) occurred when both Tac–Siro Csum ≥ 8.5 ng/mL and CNI ≥ 5 ng/mL. Notably, even with adequate CNI exposure (≥ 5 ng/mL), low Tac–Siro Csum (< 8.5 ng/mL) was associated with a higher rejection rate than sufficient cumulative exposure (p = 0.031). These findings suggest that adequate Tac–Siro exposure is critical for preventing rejection, independent of CNI levels.

Consistently, the correlation heatmap (

Figure 3) showed the strongest inverse correlation with rejection for Tac–Siro Csum (r = −0.33), compared with sirolimus (r = −0.08) and tacrolimus (r = −0.24) considered separately, underscoring the utility of Tac–Siro Csum as a composite indicator of immunosuppressive adequacy.

Renal Function and Infection Outcomes by Treatment Strategy

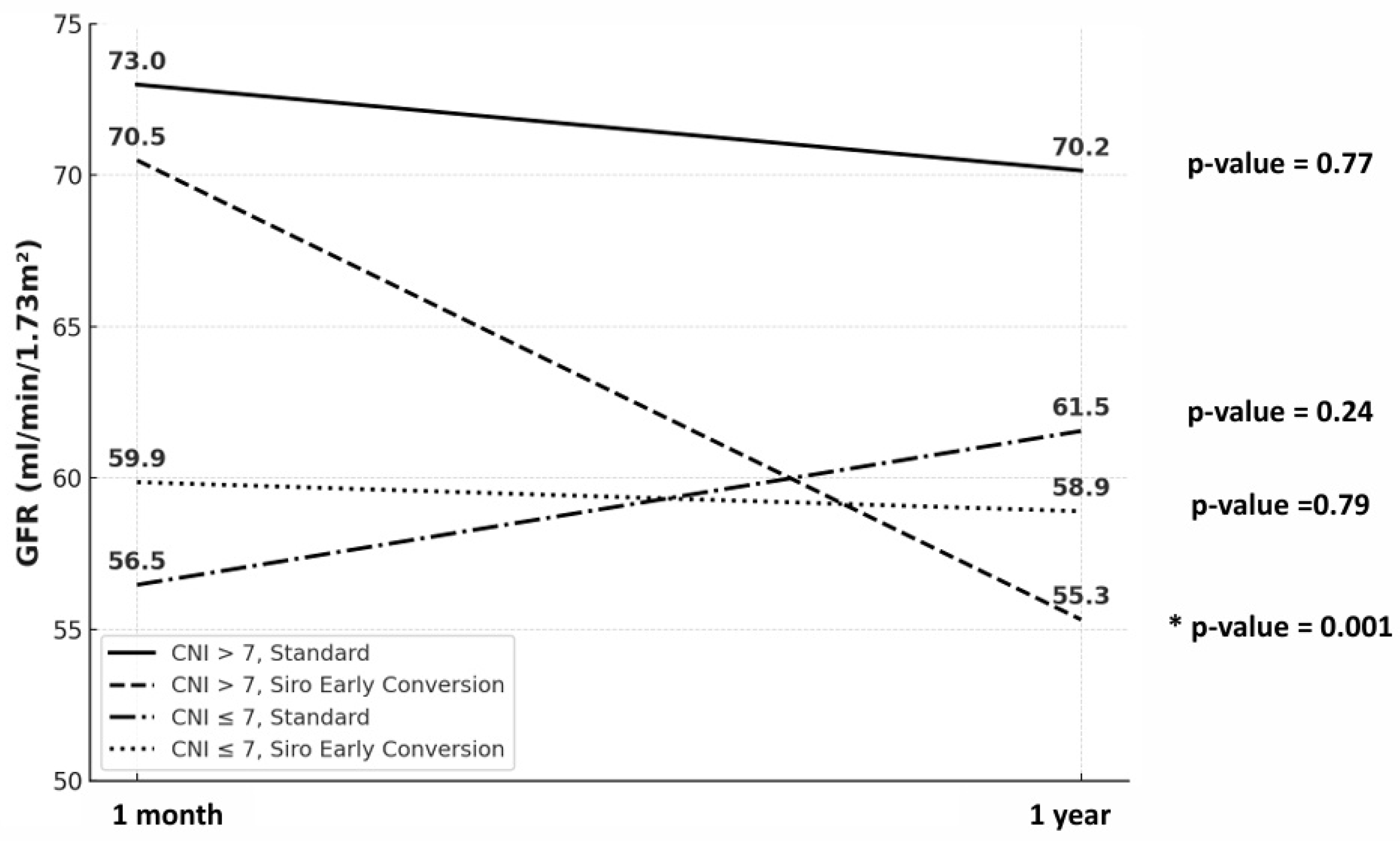

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 1 month and 1 year post-transplantation was evaluated by CNI trough level (≤ 7 vs. > 7 ng/mL) and treatment strategy (standard vs. sirolimus early conversion) (

Figure 4). Among the four subgroups, a significant eGFR decline was observed only in the > 7 ng/mL CNI with sirolimus early-conversion subgroup (p = 0.001). In contrast, the remaining subgroups (CNI > 7 standard, CNI ≤ 7 standard, and CNI ≤ 7 sirolimus early conversion) showed no statistically significant change (p = 0.77, p = 0.24, and p = 0.79, respectively).

We compared infection-related adverse events between the standard regimen and the early sirolimus conversion group (

Table 3). Hospitalizations for infection were more frequent with early conversion than with the standard regimen (22.9% vs. 15.5%;

p = 0.009). The incidence of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP) did not differ between groups (1.7% vs. 2.3%;

p = 0.73). BK viremia during 3–12 months post-transplantation was numerically lower with early conversion (4.2% vs. 6.8%) but was not significant (

p = 0.16).

Discussion

This study sought to define tacrolimus and sirolimus trough targets that yield an acute rejection rate comparable to standard triple immunosuppression in the first post-transplant year. Neither tacrolimus nor sirolimus trough alone was significantly associated with lower rejection risk versus standard therapy. Instead, cumulative exposure to both agents was the principal determinant, indicating that the combined immunosuppressive effect—rather than either drug alone—drives rejection prevention.

Prior studies have paired mTOR inhibitors with reduced-dose CNIs in kidney transplantation, using different initiation times and trough targets. The TRANSFORM study used a de novo strategy, starting everolimus at transplantation with reduced tacrolimus [

13]. Tacrolimus troughs were 4–7 ng/mL for months 0–2 and 2–4 ng/mL for months 7–24, with everolimus maintained at 3–8 ng/mL. In contrast, many early-conversion protocols, including the Korean multicenter RECORD study, initiated sirolimus later and targeted higher sirolimus levels (10–15 ng/mL after postoperative day 14) with correspondingly lower tacrolimus (3–7 ng/mL after 6 months) [

14]. A recent Chinese study targeting sirolimus at 5–7 ng/mL and tacrolimus at 3–5 ng/mL also demonstrated noninferiority for efficacy and safety [

15]. Despite differences in timing and choice of mTOR agent (everolimus vs. sirolimus), these studies consistently lowered tacrolimus exposure while titrating the mTOR inhibitor to maintain immunologic control. However, guidance on optimal Csum, especially for early-converted high-risk patients, remains lacking. Our study adds to this evidence by examining early MMF-to-sirolimus conversion and providing real-world data on combined trough levels.

Our analyses showed that Tac–Siro Csum below approximately 11.6 ng/mL was associated with a higher risk of acute rejection, with the strongest risk separation at 8.5 ng/mL based on stepwise cutoff and correlation heatmap analyses. Combined exposure, therefore, appears more predictive of acute rejection than CNI trough concentration alone. For immunologically high-risk patients, maintaining Csum ≥11.6 ng/mL may be advisable, whereas for lower-risk patients or those requiring overall immunosuppression reduction, maintaining between 8.5 and 11.6 ng/mL could be considered. However, reducing the combined concentration below 8.5 ng/mL within the first post-transplant year may carry a substantially increased risk of acute rejection. However, concurrent sirolimus with high CNI levels (≥ 7.0 ng/mL), which elevates Csum, was associated with a significant decline in eGFR. This pattern suggests a synergistic nephrotoxic interaction between tacrolimus and sirolimus, particularly in vulnerable patients. Accordingly, while Csum ≥ 11.6 ng/mL may be necessary for rejection prevention, we advise keeping CNI troughs within a reduced yet effective range (5–7 ng/mL) rather than strictly targeting ≥ 7 ng/mL. This approach aims to balance the immunologic benefit of higher Csum with protection of graft function, especially in recipients with preexisting kidney injury [

16].

Immunosuppressants are often categorized by their effects on the three signals of T-cell activation. CNIs (e.g., tacrolimus, cyclosporine) target Signal 1, downstream of T-cell receptor engagement and calcium-dependent signaling. Co-stimulation blockers (e.g., belatacept) inhibit Signal 2 by blocking CD28–CD80/86 interactions, preventing full T-cell activation. Agents acting on Signal 3—cytokine-driven T-cell proliferation—include mTOR inhibitors and MMF [

17]. Despite both being Signal 3 modulators, these classes act via distinct mechanisms.

MMF inhibits inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), blocking de novo purine synthesis and limiting proliferation of T and B lymphocytes. mTOR inhibitors, by contrast, block IL-2 receptor downstream signaling, arresting the cell cycle in activated T cells. Although their targets differ, both mTOR and CNIs converge on the IL-2–mediated activation pathway, thereby suppressing T-cell responses [

18]. These mechanistic distinctions help explain the superior efficacy of standard triple therapy—CNI, antimetabolite, and corticosteroid—particularly for preventing acute rejection. Replacing the CNI with an mTOR inhibitor has generally not matched rejection outcomes, likely because mTOR inhibition cannot fully replicate the upstream blockade achieved by CNIs [

19].

Nevertheless, substituting MMF with an mTOR inhibitor can confer clinical advantages. When paired with reduced-dose CNI and adequate combined exposure (e.g., Tac–Siro Csum ≥ 11.6 ng/mL), mTOR-based regimens may reduce nephrotoxicity relative to conventional CNI-based therapy. Several studies have also reported fewer opportunistic infections, including cytomegalovirus (CMV) and BK virus [

20,

21,

22]. In our cohort, however, infection-related hospitalizations, PCP, and BK viremia did not differ significantly between the standard and early sirolimus conversion groups. This null finding likely reflects the retrospective design rather than randomized allocation. Many patients converted to sirolimus had signs of infection—such as BK virus positivity—at conversion, which likely influenced the decision to switch from MMF. Additionally, both groups contained many recipients at moderate to high immunologic risk, potentially attenuating any antiviral advantage of mTOR-based immunosuppression.

Early postoperative mTOR inhibitor use in kidney transplantation has been linked to higher wound-complication rates [

9,

10]. Accordingly, initiation is usually deferred until complete wound healing. Although mTOR inhibitors are used to reduce CNI doses, subtherapeutic CNI exposure can increase acute rejection and de novo donor-specific antibodies (dnDSAs) [

23]. Our data indicate that combining mycophenolate with an mTOR inhibitor—rather than replacing one with the other—may confer additional immunologic benefit. This putative synergy warrants prospective evaluation [

24].

This study had limitations. First, the retrospective design limited control of confounding. PSM reduced baseline imbalances between the standard and early-conversion groups, yet the conversion cohort was small, lowering statistical power and generalizability. Second, the multicenter design prevented uniform data collection across sites; for example, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and dnDSA data were often missing and were excluded from analysis. Third, sirolimus conversion was frequently triggered by intercurrent complications (e.g., CMV or BK virus infection) rather than pre-planned. Although we adjusted by including BKV positivity at conversion in the PSM model, residual confounding is likely. Thus, baseline risk may have differed between groups.

Conclusion

This study suggests that the cumulative tacrolimus-plus-sirolimus trough level—rather than either agent alone—may be the key determinant of immunologic outcomes comparable to standard triple therapy in kidney transplantation. Maintaining a combined trough level ≥11.6 ng/mL may provide the safest immunosuppressive coverage, while 8.5–11.6 ng/mL could be considered in lower-risk or dose-reduction settings; concentrations below 8.5 ng/mL within the first post-transplant year appear to carry a markedly increased rejection risk. We also observed a possible nephrotoxic synergy between sirolimus and higher tacrolimus exposure (≥7.0 ng/mL), underscoring the need for careful trough-level optimization, particularly in recipients with preexisting renal dysfunction. Prospective randomized controlled trials are warranted to test combined mTOR inhibitor and reduced-dose CNI therapy—especially in immunologically high-risk recipients—where maintaining cumulative trough levels above approximately 11.6 ng/mL may provide effective immunosuppression while limiting nephrotoxicity.

Author Contributions

B.C., Y.K., and H.K. designed the research. B.C., Y.K., J.M.K., H.E.K., S.S., Y.H.K., J.H.J., and H.K. performed the research and acquired data. B.C., Y.K., and H.K. analyzed and interpreted data. Y.H.K., S.S., and H.K. provided methodological input. B.C., Y.K., and H.K. drafted and critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript. H.K. is the guarantor and accepts full responsibility for the data’s integrity and the accuracy of the analysis.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study followed the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center (IRB No. 2022-0139).

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for written informed consent was waived by the IRB because the study was retrospective and posed minimal risk (Level1)

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, without undue delay or restriction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Duck-Jong Han for founding the kidney and pancreas transplant programs at Asan Medical Center. Hyunwook Kwon thanks his principal supervisor, Professor Yong-Pil Cho. This study was supported by a grant (2020IT0011) from the Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vitko, S.; Klinger, M.; Salmela, K.; Wlodarczyk, Z.; Tyden, G.; Senatorski, G.; Ostrowski, M.; Fauchald, P.; Kokot, F.; Stefoni, S.; et al. Two corticosteroid-free regimens-tacrolimus monotherapy after basiliximab administration and tacrolimus/mycophenolate mofetil-in comparison with a standard triple regimen in renal transplantation: results of the Atlas study. Transplantation 2005, 80, 1734-41. [CrossRef]

- Farouk, S.S.; Rein, J.L. The Many Faces of Calcineurin Inhibitor Toxicity-What the FK? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2020, 27, 56-66. [CrossRef]

- Budde, K.; Prashar, R.; Haller, H.; Rial, M.C.; Kamar, N.; Agarwal, A.; de Fijter, J.W.; Rostaing, L.; Berger, S.P.; Djamali, A.; et al. Conversion from Calcineurin Inhibitor- to Belatacept-Based Maintenance Immunosuppression in Renal Transplant Recipients: A Randomized Phase 3b Trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2021, 32, 3252-3264. [CrossRef]

- Karpe, K.M.; Talaulikar, G.S.; Walters, G.D. Calcineurin inhibitor withdrawal or tapering for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 7, Cd006750. [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado-Payán, E.; Diekmann, F.; Cucchiari, D. Medical Aspects of mTOR Inhibition in Kidney Transplantation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 7707. [CrossRef]

- Shihab, F.; Qazi, Y.; Mulgaonkar, S.; McCague, K.; Patel, D.; Peddi, V.R.; Shaffer, D. Association of Clinical Events With Everolimus Exposure in Kidney Transplant Patients Receiving Low Doses of Tacrolimus. Am J Transplant 2017, 17, 2363-2371. [CrossRef]

- Mjörnstedt, L.; Sørensen, S.S.; von zur Mühlen, B.; Jespersen, B.; Hansen, J.M.; Bistrup, C.; Andersson, H.; Gustafsson, B.; Undset, L.H.; Fagertun, H.; et al. Improved Renal Function After Early Conversion From a Calcineurin Inhibitor to Everolimus: a Randomized Trial in Kidney Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation 2012, 12, 2744-2753. [CrossRef]

- Cortazar, F.; Molnar, M.Z.; Isakova, T.; Czira, M.E.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Roth, D.; Mucsi, I.; Wolf, M. Clinical outcomes in kidney transplant recipients receiving long-term therapy with inhibitors of the mammalian target of rapamycin. Am J Transplant 2012, 12, 379-87. [CrossRef]

- Manzia, T.M.; Carmellini, M.; Todeschini, P.; Secchi, A.; Sandrini, S.; Minetti, E.; Furian, L.; Spagnoletti, G.; Pisani, F.; Piredda, G.B.; et al. A 3-month, Multicenter, Randomized, Open-label Study to Evaluate the Impact on Wound Healing of the Early (vs Delayed) Introduction of Everolimus in De Novo Kidney Transplant Recipients, With a Follow-up Evaluation at 12 Months After Transplant (NEVERWOUND Study). Transplantation 2020, 104, 374-386. [CrossRef]

- Ueno, P.; Felipe, C.; Ferreira, A.; Cristelli, M.; Viana, L.; Mansur, J.; Basso, G.; Hannun, P.; Aguiar, W.; Tedesco Silva, H., Jr.; et al. Wound Healing Complications in Kidney Transplant Recipients Receiving Everolimus. Transplantation 2017, 101, 844-850. [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Jo, A.J.; Kwon, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, J.; Huh, K.H.; Lee, K.W.; Park, J.B.; Jang, E.; Park, S.C.; et al. Optimum tacrolimus trough levels for enhanced graft survival and safety in kidney transplantation: a retrospective multicenter real-world evidence study. Int J Surg 2024, 110, 6711-6722. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Kwon, H.E.; Han, A.; Ko, Y.; Shin, S.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, K.W.; Park, J.B.; Kwon, H.; Min, S. Risk Prediction and Management of BKPyV-DNAemia in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Multicenter Analysis of Immunosuppressive Strategies. Transpl Int 2025, 38, 14738. [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.P.; Sommerer, C.; Witzke, O.; Tedesco, H.; Chadban, S.; Mulgaonkar, S.; Qazi, Y.; de Fijter, J.W.; Oppenheimer, F.; Cruzado, J.M.; et al. Two-year outcomes in de novo renal transplant recipients receiving everolimus-facilitated calcineurin inhibitor reduction regimen from the TRANSFORM study. Am J Transplant 2019, 19, 3018-3034. [CrossRef]

- Huh, K.H.; Lee, J.G.; Ha, J.; Oh, C.K.; Ju, M.K.; Kim, C.D.; Cho, H.R.; Jung, C.W.; Lim, B.J.; Kim, Y.S. De novo low-dose sirolimus versus mycophenolate mofetil in combination with extended-release tacrolimus in kidney transplant recipients: a multicentre, open-label, randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017, 32, 1415-1424. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.Y.; Dai, L.R.; Hou, Y.B.; Yu, C.Z.; Chen, R.J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Liu, B.; Shi, H.B.; Gong, N.Q.; Chen, Z.S.; et al. Sirolimus in combination with low-dose extended-release tacrolimus in kidney transplant recipients. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1281939. [CrossRef]

- Rangan, G.K. Sirolimus-associated proteinuria and renal dysfunction. Drug Saf 2006, 29, 1153-61. [CrossRef]

- A, M. Immunosuppressive Agents; American College of Clinical Pharmacy: Lenexa, KS, 2011.

- Halloran, P.F. Immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med 2004, 351, 2715-29. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, D.; Hernández, D.; Martínez, D.; Martínez, D.; Gutiérrez, E.; Gutiérrez, E.; López, V.; López, V.; Gutiérrez, C.; Gutiérrez, C.; et al. CLINICAL EVIDENCE ON THE USE OF ANTI-mTOR DRUGS IN RENAL TRANSPLANTATION. Nefrología (English Edition) 2011, 31, 27-34. [CrossRef]

- Fantus, D.; Rogers, N.M.; Grahammer, F.; Huber, T.B.; Thomson, A.W. Roles of mTOR complexes in the kidney: implications for renal disease and transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol 2016, 12, 587-609. [CrossRef]

- Mallat, S.G.; Tanios, B.Y.; Itani, H.S.; Lotfi, T.; McMullan, C.; Gabardi, S.; Akl, E.A.; Azzi, J.R. CMV and BKPyV Infections in Renal Transplant Recipients Receiving an mTOR Inhibitor-Based Regimen Versus a CNI-Based Regimen: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized, Controlled Trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017, 12, 1321-1336. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.L.; Wu, B.S.; Lien, T.J.; Yang, A.H.; Yang, C.Y. BK Polyomavirus Nephropathy in Kidney Transplantation: Balancing Rejection and Infection. Viruses 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Gralla, J.; Klem, P.; Tong, S.; Wedermyer, G.; Freed, B.; Wiseman, A.; Cooper, J.E. Lower tacrolimus exposure and time in therapeutic range increase the risk of de novo donor-specific antibodies in the first year of kidney transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation 2018, 18, 907-915. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, P.; Englund, B.; Ekberg, J.; Felldin, M.; Broecker, V.; Mjornstedt, L.; Baid-Agrawal, S. Difficult-to-Treat Rejections in Kidney Transplant Recipients: Our Experience with Everolimus-Based Quadruple Maintenance Therapy. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).